Business & Professional Ethics Textbook for Directors, Executives

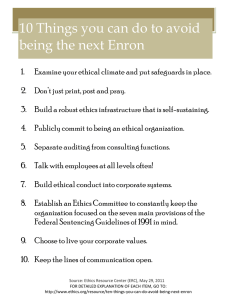

advertisement