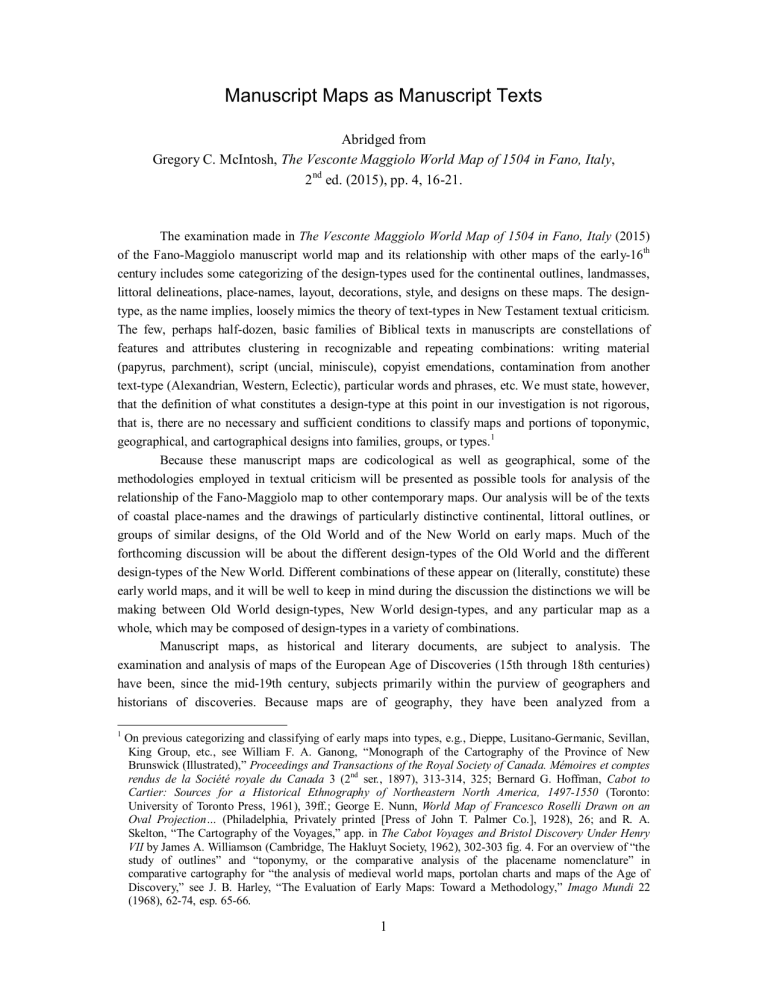

Manuscript Maps as Manuscript Texts Abridged from Gregory C. McIntosh, The Vesconte Maggiolo World Map of 1504 in Fano, Italy, 2 nd ed. (2015), pp. 4, 16-21. The examination made in The Vesconte Maggiolo World Map of 1504 in Fano, Italy (2015) of the Fano-Maggiolo manuscript world map and its relationship with other maps of the early-16th century includes some categorizing of the design-types used for the continental outlines, landmasses, littoral delineations, place-names, layout, decorations, style, and designs on these maps. The designtype, as the name implies, loosely mimics the theory of text-types in New Testament textual criticism. The few, perhaps half-dozen, basic families of Biblical texts in manuscripts are constellations of features and attributes clustering in recognizable and repeating combinations: writing material (papyrus, parchment), script (uncial, miniscule), copyist emendations, contamination from another text-type (Alexandrian, Western, Eclectic), particular words and phrases, etc. We must state, however, that the definition of what constitutes a design-type at this point in our investigation is not rigorous, that is, there are no necessary and sufficient conditions to classify maps and portions of toponymic, geographical, and cartographical designs into families, groups, or types.1 Because these manuscript maps are codicological as well as geographical, some of the methodologies employed in textual criticism will be presented as possible tools for analysis of the relationship of the Fano-Maggiolo map to other contemporary maps. Our analysis will be of the texts of coastal place-names and the drawings of particularly distinctive continental, littoral outlines, or groups of similar designs, of the Old World and of the New World on early maps. Much of the forthcoming discussion will be about the different design-types of the Old World and the different design-types of the New World. Different combinations of these appear on (literally, constitute) these early world maps, and it will be well to keep in mind during the discussion the distinctions we will be making between Old World design-types, New World design-types, and any particular map as a whole, which may be composed of design-types in a variety of combinations. Manuscript maps, as historical and literary documents, are subject to analysis. The examination and analysis of maps of the European Age of Discoveries (15th through 18th centuries) have been, since the mid-19th century, subjects primarily within the purview of geographers and historians of discoveries. Because maps are of geography, they have been analyzed from a 1 On previous categorizing and classifying of early maps into types, e.g., Dieppe, Lusitano-Germanic, Sevillan, King Group, etc., see William F. A. Ganong, “Monograph of the Cartography of the Province of New Brunswick (Illustrated),” Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. Mémoires et comptes rendus de la Société royale du Canada 3 (2nd ser., 1897), 313-314, 325; Bernard G. Hoffman, Cabot to Cartier: Sources for a Historical Ethnography of Northeastern North America, 1497-1550 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961), 39ff.; George E. Nunn, World Map of Francesco Roselli Drawn on an Oval Projection… (Philadelphia, Privately printed [Press of John T. Palmer Co.], 1928), 26; and R. A. Skelton, “The Cartography of the Voyages,” app. in The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery Under Henry VII by James A. Williamson (Cambridge, The Hakluyt Society, 1962), 302-303 fig. 4. For an overview of “the study of outlines” and “toponymy, or the comparative analysis of the placename nomenclature” in comparative cartography for “the analysis of medieval world maps, portolan charts and maps of the Age of Discovery,” see J. B. Harley, “The Evaluation of Early Maps: Toward a Methodology,” Imago Mundi 22 (1968), 62-74, esp. 65-66. 1 McIntosh – Manuscript Maps as Manuscript Texts geographical point of view. But, by the same reasoning, does that mean the primary analytical approach to the paintings of Raphael, for example, which were predominately of saints and holy figures, should be from a religious point of view? Of course not. It is not exclusively the subject matter that matters. Just as we may question whether the history of religion should be the primary analytical approach to paintings of the Renaissance, so too may we question whether the history of geography should be the primary analytical approach to world maps of the Renaissance. The tools and methods of textual criticism may be applicable to the analysis of the transmission of place-names, continental outlines, and cartographic designs of manuscript (and printed) maps. Textual criticism is the scholarly and critical study of a particular text emphasizing a close reading and detailed analysis of variant texts, usually manuscripts, and usually sacred or classical. Textual criticism is specifically interested in the identification and elimination of significant transmission errors in manuscripts (e.g., miscopying, misspellings, repeated words or phrases, omitted words and phrases, altered sequence, interpolated material, substituted wording, corrected grammar, etc.). The purpose in identifying and eliminating errors of a text is to attempt a reconstruction of the original text. The methods of manuscript text production invite accidental errors in copying. After a variant (or error) is introduced into a text, it has a tendency to be reproduced in subsequent copies. These copying errors, repeated by subsequent copyists, often over centuries, therefore, provide a genealogy of variants and, hence, a genealogy of the manuscript texts. By comparing manuscripts and studying their patterns of variation, textual criticism can sort (collate) them into general types (families) and subtypes and trace their relationships.2 Included in the several methodologies of textual criticism is stemmatics or stemmatology, the study of surviving manuscript versions of the same text with the immediate goal of constructing a stemma, family tree, or diagram of the relationships of the extant manuscripts (witnesses) to each other. The history of a manuscript textual tradition may be recovered from analysis of variant readings. In the case of maps, our identification of a manuscript map tradition includes not only the word-text (commentary, inscriptions, legends, and place-names) written on the map, but also paratextual material. 3 Paratextual material on maps may include geographical ideas and theories, designs, coasts, seas, mountains, illustrations, pigmentations, scrolls, animals, towns, people, wind roses, flags, etc. In textual criticism, variants due to miscopying are usually readily evident: misspellings, omissions, duplications, etc. In maps, however, the place-names were often unfamiliar to the copyist (or mapmaker or lector or calligrapher), sometimes in a language foreign to the copyist, even foreign to Europeans, and almost always only as a word or two in length without context. Textual criticism, through the application of its tools, can often recover the original sense of a written statement, whereas the original or earliest text of the maps (place-names) cannot be relatively so easily recovered or reconstructed. In the use of stemmatics for map analysis, the focus is not 2 Mutilation — the disappearance by external circumstances of a word or words in a text, or a place-name or part of a place-name on a map — is generally not considered a transmission error that is due to the action of the copyist. There are, interestingly, however, instances, discussed in the text and tables of The Vesconte Maggiolo World Map of 1504 in Fano, Italy, of the remnant of a partially effaced or mutilated place-name on a source map being copied as a whole word onto the derivative map. 3 Gérard Genette,, Palimpsestes: la litterature au second degré (Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1982), 9; Gérard Genette,, Seuils (Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1987), 7. Outside of historical studies, another meaning of paratext (beyond text) is for electronic forms of transmission, e.g., telephone, radio, film, television, photocopying, CD-ROM, etc.; see Ronald K. L. Collins and David M. Skover, “Paratexts,” Stanford Law Review 44 (no. 3, February 1992), 510. 2 McIntosh – Manuscript Maps as Manuscript Texts exclusively, nor even primarily upon the textual sources used by mapmakers, that is, a text-to-map transmission, nor upon the ultimate origin or meaning of a place-name. Rather, the focus is upon the transmission from map-to-map of clusters of distinctive features and place-names (design-types). The application of the tools of literary analysis, philology, historical criticism, and textual criticism, on the one hand (maps as texts), and the tools of art history (maps as graphics and aesthetics), on the other, have yet to be more fully applied to the study of these old maps. These maps, both manuscript and printed, were not each individually created in a vacuum. They were copied from earlier maps, or parts of earlier maps, and often compiled or amalgamated from several maps. They were made by “copying” in the broadest sense of the word and are, therefore, still susceptible to some degree of analysis. We can be reasonably certain of the primary exemplar (Cantino planisphere), and the planispheres under review certainly are closely related in several ways. The long list of coastal placenames snaking around the parchments constitutes an essentially uniform body of text that is similar among the maps. This fairly consistent body of place-name text is susceptible to transmission errors and, thus, subject to stemmatic analysis. For want of a better word, we will call an effectively unvarying list of place-names tied to a specific coastline on a map a toponymy. These planispheres are, of course, as are all maps, mixtures of other maps, texts, geographies, reports, and theories. Therefore, in the case of old maps, the Earth is not the archetype. If anything, the archetype is the image in the mapmaker’s mind.4 The traditional goal in textual criticism is to produce (reconstruct) a text most closely approximating the original text (archetype). A significant portion of the process of reaching that goal is performed by determining the relationships of the texts to each other through the identification and transmission of transcription variants. Copying always involves some adaptation. 5 Unlike textual criticism, however, because there are no “correct” readings for the place-names on the maps, there are no errors, only variants. It is, of course, true that these maps are filled with misspellings and copying errors, but because we are not seeking the archetype of the text, there are no correct spellings, only variants, some earlier, some derivative. Our goal in the present review of the Fano-Maggiolo, Caverio, and other manuscript maps is limited to working out their filiation and tracing their descent through the transmission of textual and paratextual variants and geographical design-types but without the intent of reconstructing an archetype (and the inherent prejudices associated with an intent). Each map, including one copied from another, is a new production rather than an imperfect copy of an earlier source.6 Though the quantity of the same or similar place-names among the maps indicates they are members of the same stemma, or family tree, of manuscripts (or, at least, participate in a common pool of place-names), the variety of names and spelling variants indicate there must be 4 This is not, of course, true of modern cartography. Not recognizing this distinction in studying early 16th century maps (actually applicable to all “science” before the Age of Enlightenment), however, has led some to expend a tremendous amount of ink comparing coastlines on old maps (while ignoring the place-names) with coastlines on modern maps, as though the coastlines on old charts were drawn for the same purposes with the same methods from the same sources as modern charts. Prior to the 18th century, cartographers typically included hypothetical, conjectural, or imaginary lands on their world maps. 5 To copy is to miscopy. 6 On types of manuscript text contamination (simultan, gemisch, sukzessiv) similar to those of the maps under review, that is, uniting large portions and entire sections from multiple sources into a new whole, see Gerd Simon, “Zur Theorie der Kontamination,” in Maschinelle Verarbeitung altdeutschen Texte, Beiträge zum Symposion, Mannheim, 11-12 Juni 1971, ed. Winfried Lenders and Hugo Moser, 2 vols. (Berlin, Erich Schmidt, 1978), 1:108-116. 3 McIntosh – Manuscript Maps as Manuscript Texts some unconscious errors (miscopying), conscious emendations (sophistication), multiple sources (contamination), or intermediate copies. Unlike the familiar manuscript transmission of Biblical texts, for manuscript maps there is little if any correcting process wherein the coastal place-names on a map are re-read and emended to correctly match an exemplar, such as another map or a text. We should probably approach early manuscript maps with some caution and presume they are most likely both contaminated and sophisticated manuscript texts. An observation regarding medieval manuscript poems is also applicable to mapmaking: “[E]ach act of copying was to a large extent an act of recomposition, and not an episode in a process of decomposition from an ideal form.”7 Few, if any, mapmakers, while creating a new map (printed or manuscript) by copying a base map, did not also augment that cartography with additional information. Rather than being a hindrance to determining the “best” text, that is, a reconstructed text most like the archetype (the goal of textual criticism), as a contaminated text, a map derived from multiple sources aids in determining the genealogy of the map as a manuscript, the sources used by the mapmaker, the processes of map production, the milieu of its making, and the history of the transmission (through time and over distances) of geographical ideas. Whereas textual criticism and textual analysis use stemmatics as a tool to reach the goal, we will hold stemmatics as the goal. We seek to trace the genealogy of the changes brought about by using more than one source and by introducing original material — both practices mapmakers perform as part of their craft — along with the other copying processes that create textual variants, to determine the filiation of the maps for its own sake. The design-type, as we are using the term, is a group of similar geographic, cartographic, toponymic, and decorative elements that appear on maps, not a collection of maps. The geographical depictions, littoral delineations, and decorative elements, as illustrative material, are paratextual. A single map may be composed of several design-types: Scandinavia (Portolan, Clavus Type-A, or Clavus Type B), Britain (Ptolemy or Portolan), South Asia (Ptolemy, Martellus, or Padrão), Caspian Sea (Ptolemy, Vesconte, or Fra Mauro), Greenland (Clavus, Donnus, Lusitano-Germanic, or King), East Asia (Angular Mangi Peninsula, Hanging Mangi Peninsula, or Padrão), etc. Maps of the early sixteenth century usually display various combinations of these design-types. Some notable examples: New World Scandinavia Britain South Asia Caspian Sea Greenland Cantino LusitanoGermanic Portolantype Portolantype Padrão-type n/a LusitanoGermanic King-Hamy King-type Clavus Type II-B Ptolemy King-type Ptolemy King-type ContariniRosselli King-type Clavus Type II-B Portolantype King-type Ptolemy King-type Fano-Maggiolo King-type Portolantype Portolantype Padrão-type Fra Mauro King-type Waldseemüller LusitanoGermanic Clavus Type II-B Ptolemy Ptolemy Ptolemy Clavus Type II-B Most manuscript world maps of the 15th and 16th centuries display geographical design-types copied from other maps, usually other manuscript maps. This means that some geographical depictions (littoral outlines, continental shapes, etc.) and text (place-names) on manuscript maps are 7 Derek Pearsall, “Texts, Textual Criticism and Fifteenth Century Manuscript Production,” in Fifteenth Century Studies: Recent Essays, ed. Robert F. Yeager (Hamden, Connecticut, Archon Books, 1984), 127. 4 McIntosh – Manuscript Maps as Manuscript Texts derivative of other manuscript maps. Often, of course, in creating a map, a mapmaker will also use other, non-cartographic sources, such as travel reports, classical authorities, oral narratives, etc. Other manuscript maps, though not descended from one another, are relatives — both derive their designtypes (continental outlines and place-names) from some common ancestor. Some maps are close relatives, others are distant. In this sense, manuscript maps are like people, though maps often have more than two “parents.” The study of the kinships in texts and designs tries to make sense of these various relationships. The results can be used to trace the history of the maps, the development of the cartography, the evolution of geographical ideas, and the spread of knowledge through scholarly and commercial activities. 5