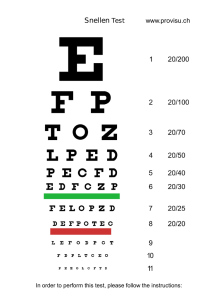

“ The Object Lessons series achieves something very close to magic: the books take ordinary—even banal—objects and animate them with a rich history of invention, political struggle, science, and popular mythology. Filled with fascinating details and conveyed in sharp, accessible prose, the books make the everyday world come to life. Be warned: once you’ve read a few of these, you’ll start walking around your house, picking up random objects, and musing aloud: ‘I wonder what the story is behind this thing?’ ” Steven Johnson, author of Where Good Ideas “ Come From and How We Got to Now Object Lessons describes themselves as ‘short, beautiful books,’ and to that, I’ll say, amen. . . . If you read enough Object Lessons books, you’ll fill your head with plenty of trivia to amaze and annoy your friends and loved ones— caution recommended on pontificating on the objects surrounding you. More importantly, though . . . they inspire us to take a second look at parts of the everyday that we’ve taken for granted. These are not so much lessons about the objects themselves, but opportunities for self-reflection and storytelling. They remind us that we are surrounded by a wondrous world, as long as we care to look.” John Warner, The Chicago Tribune “ In 1957 the French critic and semiotician Roland Barthes published Mythologies, a groundbreaking series of essays in which he analysed the popular culture of his day, from laundry detergent to the face of Greta Garbo, professional wrestling to the Citroën DS. This series of short books, Object Lessons, continues the tradition.” Melissa Harrison, Financial Times “ “ Though short, at roughly 25,000 words apiece, these books are anything but slight.” Marina Benjamin, New Statesman The Object Lessons project, edited by game theory legend Ian Bogost and cultural studies academic Christopher Schaberg, commissions short essays and small, beautiful books about everyday objects from shipping containers to toast. The Atlantic hosts a collection of ‘mini object-lessons’. . . . More substantive is Bloomsbury’s collection of small, gorgeously designed books that delve into their subjects in much more depth.” Cory Doctorow, Boing Boing “ The joy of the series . . . lies in encountering the various turns through which each of the authors has been put by his or her object. The object predominates, sits squarely center stage, directs the action. The object decides the genre, the chronology, and the limits of the study. Accordingly, the author has to take her cue from the thing she chose or that chose her. The result is a wonderfully uneven series of books, each one a thing unto itself.” “ “ Julian Yates, Los Angeles Review of Books . . . edifying and entertaining . . . perfect for slipping in a pocket and pulling out when life is on hold.” Sarah Murdoch, Toronto Star . . . a sensibility somewhere between Roland Barthes and Wes Anderson.” Simon Reynolds, author of Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past iv A book series about the hidden lives of ordinary things. Series Editors: Ian Bogost and Christopher Schaberg Advisory Board: Sara Ahmed, Jane Bennett, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Johanna Drucker, Raiford Guins, Graham Harman, renée hoogland, Pam Houston, Eileen Joy, Douglas Kahn, Daniel Miller, Esther Milne, Timothy Morton, Kathleen Stewart, Nigel Thrift, Rob Walker, Michele White. In association with Books in the series Remote Control by Caetlin Benson-Allott Golf Ball by Harry Brown Driver’s License by Meredith Castile Drone by Adam Rothstein Silence by John Biguenet Glass by John Garrison Phone Booth by Ariana Kelly Refrigerator by Jonathan Rees Waste by Brian Thill Hotel by Joanna Walsh Hood by Alison Kinney Dust by Michael Marder Shipping Container by Craig Martin Cigarette Lighter by Jack Pendarvis Bookshelf by Lydia Pyne Password by Martin Paul Eve Questionnaire by Evan Kindley Hair by Scott Lowe Bread by Scott Cutler Shershow Tree by Matthew Battles Earth by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Linda T. Elkins-Tanton Traffic by Paul Josephson Egg by Nicole Walker Tumor by Anna Leahy Personal Stereo by Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow Whale Song by Margret Grebowicz Eye Chart by William Germano Shopping Mall by Matthew Newton Sock by Kim Adrian Jet Lag by Christopher J. Lee Veil by Rafia Zakaria High Heel by Summer Brennan (forthcoming) Souvenir by Rolf Potts (forthcoming) Rust by Jean-Michel Rabaté (forthcoming) Luggage by Susan Harlan (forthcoming) Burger by Carol J. Adams (forthcoming) Toilet by Matthew Alastair Pearson (forthcoming) Blanket by Kara Thompson (forthcoming) eye chart william Germano Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc N E W YO R K • LO N D O N • OX F O R D • N E W D E L H I • SY DN EY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc 1385 Broadway New York NY 10018 USA 50 Bedford Square London WC1B 3DP UK www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2017 © William Germano, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Germano, William P., 1950Title: Eye chart / William Germano. Description: New York : Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. | Series: Object lessons | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017003955 (print) | LCCN 2017006704 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501312342 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781501312328 (ePub) | ISBN 9781501312311 (ePDF) Subjects: LCSH: Eye–Examination–History. | Vision–Testing–History. | Visual perception–History. | Visual perception–Psychological aspects. | Charts, diagrams, etc. Classification: LCC RE26 .G47 2017 (print) | LCC RE26 (ebook) | DDC 612.8/4–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017003955 ISBN: PB: 978-1-5013-1234-2 ePub: 978-1-5013-1232-8 ePDF: 978-1-5013-1231-1 Series: Object Lessons Cover design: Alice Marwick Typeset by Deanta Global Publishing Services, Chennai, India for Diane and Christian, clearly “Can you read this?” Ophthalmologist to patient. (Anytime, anywhere.) “Everyone is committed to the optical illusions of his isolated standpoint.” walter benjamin, one-way street x Contents List of figures xiii 1 What can you see? 1 2 Reading stars, reading stones 13 3 How to choose eyeglasses (circa 1623) 4 The persistence of memory 5 Eleven lines, nine letters 6 Reading up close 77 7 Looking for trouble 8 Eye terror 103 9 Eye poetry 117 91 55 41 23 10 Optical allusions 11 The bottom line Acknowledgments 155 Notes 157 Index 165 xii Contents 129 147 LIST OF FIGURES 1.1 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 4.1 4.2 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 6.1 6.2 6.3 7.1 8.1 8.2 Herman Snellen’s carte de visite. 11 A 1920s optometer. 24 Uso de los antojos, title page. 28 Francis Bacon, Sylva Sylvarum, title page. 30 Testing image from Uso de los antojos. 32 Testing image from Uso de los antojos. 33 A sermon can test eyes, too. 47 The Küchler chart. 49 Testing with Egyptian Paragon. 67 The Landolt C eye chart. 69 Degas, The Fallen Jockey (detail). 71 The logMAR eye chart. 73 The Mayerle eye chart (1907). 75 A moment of Goethe in Jaeger’s test-types. 79 Testing vision with Schiller. 80 Jaeger, and Jaeger with music. 83 Mr. Magoo negotiates an unlikely eye chart. 100 The invisible man’s deathbed visibility. The Invisible Man, dir. James Whale, 1933. 107 Superman fails an eye test. 109 9.1 George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” tests many things, including eyes. 120 9.2 Mouse tail “stereotype plate” from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a second issue of the first edition of “Alice” photographed by Jack Campbell-Smith for Oxford University Press. Reproduced by permission. 125 10.1 Bottoms up. Shot glasses with diagnostic benefits. Source: Restoration Hardware. 134 10.2 The Pi eye chart. 136 10.3 Urban geography as cultural eye test. 137 10.4 The most comforting eye chart ever devised. 138 10.5 Message Snellen and optical understanding. 1936 or 1937. WPA Federal Art Project. 139 10.6 Evangelical Snellen. 140 10.7 Drunk Snellen. 141 10.8 Tattoo Snellen. “Ben Ross Davis, New York 2016.” Photograph: William Germano. 143 10.9 Inking belief in Snellen terms. Photograph: Ina Saltz; artist: Anthony Morelli. From Body Type 2: More Typographic Tattoos by Ina Saltz. New York, Abrams Image, 2010. 144 10.10 Do-it-yourself Snellen. 145 10.11 Do-it-yourself Jaeger. 146 xiv LIST OF FIGURES 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Eye testing in a Sudanese village. Photo courtesy of the World Health Organization. © WHO/Didier Henrioud, 1975. 148 Snellen as an Indian public service announcement. https://www.newswire.com/sankara-eye-hospitalunveils-world/198658 October 12, 2012. Accessed June 5, 2016. Originally appeared in the Times of India. 149 Eye-test posters. Tromsø, Norway. Photograph: William Germano, 2016. 150 Snellen as graphic style. A gallery sign in Ljubljana. Photograph: William Germano, 2014. 153 [Your answer here.] Image © Aled Lewis. Used with permission of the artist. 154 LIST OF FIGURES xv xvi 1 What Can You See? At ten o’clock on the morning of May 13, 1885, at the (now defunct) Pulte Medical College in Cincinnati, a meeting of the Homeopathic Medical Society of Ohio was called to order. Helen Varner, the event’s secretary, subtitled her report “An Interesting and Profitable Meeting.” Paper topics ranged from the descriptive (the disposal of the dead in New Orleans) and the diagnostic (a paper on breech delivery, that was pleasingly delivered “in a softly modulated voice”) to the weirdly pre-scientific (the probability of planetary conjunctions causing storms on Earth). There was debate on the subject of cremation. Was it Christian? One speaker protested eloquently that without interment of the body “there would have been no burial of Christ nor Lazarus, no ‘Hamlet’ without the grave scene, no ‘Thanatopsis,’ no harrowing mourners.” A busy day. “Toward the end of the session,” Miss Varner continues, “the bureau of O. and O. [Optometry and Ophthalmology] contributed a paper on Ophthalmologic mistakes by Dr. Phillips, who urged care in differential diagnosis. Glaucoma, by Dr. Shell, followed by a recommendation of an eye chart, by Dr. McDermott. I fancied there were many who were disappointed at not hearing from Dr. McDermott. Few know better how to electrify an audience than this gentleman.”1 We might still regret the absence of Dr. McDermott. A man who could have electrified an audience even with a talk recommending an eye chart is a man worth hearing. What would he have shown a Cincinnati audience in 1885? Probably some version of Herman Snellen’s optotypes, a simple graphic of sample letters devised in the Netherlands in 1862. It would quickly become the gold standard of visual testing. E For a hundred and fifty years it’s been the most successful graphic yet devised for determining the acuity of vision. Snellen’s eye chart, the Snellen chart—we don’t refer to Snellen’s optotypes anymore—is so familiar that it seems always to have been there. Dr. McDermott’s audience may even have been hearing eye chart as a new medical term; the Oxford English Dictionary tells us that Miss Varner’s report of the event is the earliest documented appearance of eye chart in the English language.2 It stuck. From Utrecht to Cincinnati to the rest 2 eye chart of the English-speaking world, we speak of eye charts, and when we do we’re almost always talking about Snellen’s handiwork or some version of it. It’s not even medicine’s property anymore. Once just the name for a diagnostic tool, eye chart has become part of popular culture’s toolkit, lending its authority to graphic design and conceptual art. The Snellen eye chart is a powerful if enigmatic thing. I’ve worn glasses all my life, and so I’ve had to return to that chart again and again; different doctors’ offices, different versions of the Snellen chart, but always the same procedure. In a modern, darkened space, the image revealed—after so many years, a ceremony as much as an exam. For me, eye charts are nocturnal creatures, like vampires and ghosts. They belong in the dimness of the examining room. I had mixed feelings when eye charts became a trope of graphic design. That’s clever, I thought, the first time I saw a Snellen diagram silk-screened on a T-shirt. But I wondered what it was doing there. Snellen and I have gone way past that point, so far in fact that I’ve come back to the eye chart as an object I wanted to think about in some detail. Who was Snellen? Where did eye charts come from? How do they work? How did the graphic we know become an icon of design? For that matter, when did people begin connecting eyeglasses, which I knew were a medieval invention, to tests for visual acuity? The eye chart is a test, and just one of many. Doctors and nurses test parts of us, inside and out, reporting to us what they’ve discovered about good cholesterol or bone density What Can You See? 3 or odd marks in odd places. The modern medical exam can feel overwhelmingly passive. We obediently submit and our bodies give up the secrets that even we ourselves may not want to know. The eye exam is yet one more medical test requiring obedient submission (do not move, look at my left ear, do not blink), but one part of it—the eye chart—provides a kind of relief from the control of medical authority. It’s the rare test where—in a literal sense—you get to read the signs. Familiar and unfamiliar, like many things around us, the eye chart is something we don’t notice until we have to. This isn’t especially surprising. How often do you see your eye doctor? Once a year? That’s the frequency for which the eye chart was designed to be seen, like a Christmas ornament or an Easter egg. What’s different about the eye chart, however, is that it’s not just an object to be seen but to be studied, and it’s an object that is in itself all about noticing. Scientific and non-scientific, clinical and symbolic, the eye chart shows multiple faces. Like any other scientific tool, this one communicates its findings as precisely as possible and in a universal language of measurement. Facing us with its cool display of letters, the eye chart is something more, too. It’s not just a tool but a text—enigmatic, partially readable, and ultimately illegible. E The visual document we know was configured by a twentyeight-year-old Dutch ophthalmologist. Herman Snellen’s professional life was largely confined to Utrecht, where he 4 eye chart had studied ophthalmology and worked as an assistant to Franciscus Donders, founder of the Nederlandsch Gasthuis voor Ooglijders (the Dutch hospital for eye disorders); Snellen would succeed Donders as its head. As with many medical innovators, it’s not the day-to-day treatment of patients or scholarly papers for which Snellen would be remembered, but for one instantly popular eye test. Despite the Snellen diagram’s sudden fame and continuing utility, the idea of an eye chart was not itself new. For a quarter century before Snellen’s 1862 breakthrough, there had been standardized printed material of various kinds to test eyesight. At the same time that Donders and Snellen were at work, visual testing was also being explored by Eduard Jaeger, Snellen’s Austrian contemporary and sometimes rival. Snellen plus Jaeger: you probably think of the eye chart only as the graphic arrangement of letters in a darkened room and forget about the small handheld card with text on it. “Hold this at your normal reading distance,” your ophthalmologist might say, and you dutifully read off a patch of text. That card is the second, participatory element in your eye exam, and it’s about reading, not identifying. Eduard Jaeger made this part of the protocol. While Snellen crafted an ingenious mechanism for specifying vision strength at a distance, Jaeger provided a tool for evaluating vision close in. You may not think of Jaeger’s contribution, which seems so ordinary as to escape attention, but when you go for an eye check-up today you enter a world made possible by Snellen What Can You See? 5 and Jaeger, whose contributions to diagnosis gave system to the process of analyzing visual accuracy. Nevertheless, today it’s still Snellen’s name we know best. The young Dutch doctor who organized this set of symbols became the unwitting father of a gesture in graphic design that links the contemporary world to mid-nineteenthcentury ophthalmological practice. No graphic work in the history of medicine is more easily recognizable than Snellen’s eye chart. E The eye chart you know is a card or projection with letters arranged from largest at the top to smallest at the bottom. Universally recognized as a diagnostic tool for assessing the acuity of a person’s vision, the eye chart provides calibrations that can be shared among vision professionals—the ophthalmologist or optometrist who examines you, as well as the optician who grinds your lenses. Like all good scientific tools, it promises accurate, transferable data. In the mid-twentieth century, however, the eye chart began to take on a graphic and social life of its own. No longer the thing you would see once a year on a visit to the doctor’s office, the eye chart began to pop up everywhere— in advertising, in cartoons, turning up on T-shirts and postcards, toys and tchotchkes. Modern design has mined the Snellen chart for its graphic ingenuity, disassembling and repurposing it for humor, exhortation, satire, politics, and 6 eye chart even devotional purposes. For the doctor it’s a diagnostic tool. For us civilians it’s become a point of reference for other graphics that, unlike Snellen’s cryptic arrangement, have something to say. In his late essay Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes wrote that “photography is at the intersection of two quite distinct procedures,” the chemical and the optical.3 Materials interact and cause an image to emerge in a bath under a safelight as silver particles adhere to paper. Physical and psychological processes enable an image of something in the visible world to reach the iris, the retina, the brain. Like photography, the measurement of visual acuity also occurs at the intersection of two quite distinct procedures. As embodied in the Snellen eye chart and the Jaeger reading card, these two procedures are both about forms of reading: far vs. near, letters vs. text, symbols vs. narrative. Together the two components make up a more elastic idea of an “eye chart”—the catchy layout of Snellen’s letters and Jaeger’s quiet display of text samples. Eye chart: One of the many compounds for the word eye recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary. You can compile an eccentric list. What do you call the reflection of yourself that you glimpse in another person’s eye? An eye baby. What do you call a sense of ungrounded optimism based purely on how things appear? Eye hope. The form eye-mindedness is an infrequent term for visual memory. If you’re eye-set you’re trustworthy. You won’t see well if you have an eye-pearl, which isn’t a gem, unfortunately, but a cataract. An eyeseed is, surprisingly What Can You See? 7 enough, actually a kind of seed, but it’s one which, when placed in the eye, was once believed to bring about sympathetic magic and remove foreign material from the body. Diagnostic or playful, clinical or personal, the eye chart functions both as a thing and as a syntactic arrangement. That range means that we can think about the eye chart in terms both of its history as a diagnostic tool and as a popular form of information delivery. We might even do more and consider how the eye chart, with its hierarchy and clear-cut performance thresholds, invites us to ponder metrics and standards and conventions, forms of legibility and invisibility, and even ideas of the normal. The precise measurement of vision shares objectives with other modern projects: the expansion of literacy, the invention of the telescope, the development of the modern army, the ambitions of modern advertising, the poetry of the everyday—all have connections to the eye test, and to the eye chart that remains its graphic centerpiece. It’s always been important for humans to know who in the group had the best pair of eyes. Then in the experimental world of early modernity, and again in the technological nineteenth century, the goal of measuring visual acuity with some precision becomes part of what we might call the project of the eye. That project is optical. The eye chart works by playing a trick on us: it takes things we can easily see—objects, words, letters—and makes them difficult to distinguish. The figures on the chart may be precise, but fuzziness is built into the eye chart’s architecture. 8 eye chart Form is as crucial to the eye chart as it is to dance or grammar. A standard Snellen chart, for example, has eleven lines of type. You’re not really supposed to be able to read all eleven of them, though there are a few people who can, but they fall outside that band of performance to which we assign the categorical name average (and sometimes normal). Reading through the whole thing isn’t the point. As a diagnostic tool, the eye chart depends on uncertainty, the presence of the border, the space between the sharp and the fuzzy, the no-man’s-land between the clear and the ambiguous. It’s the edge that the eye chart tests for. How to describe the dynamic of the eye chart? In a different context, the psychoanalytic critic Kaja Silverman has used the phrase “the threshold of the visible world.” The eye chart feels like a variant on that concept. It’s a graphic world that represents, for diagnostic purposes, our visible threshold. Our eyes are us. Our windows, our points of contact, our lifelong projects, the way the heart and the back and the gut are lifelong projects. We point to computers and complain of eyestrain, or we face the inevitable decline of vision with age (presbyopia, which only sounds like what Presbyterians see but simply means elderly vision). We learn to care for our eyes. We learn about irregularities in the shape of the eyeball and the difference in nearsightedness (myopia) and farsightedness (hyperopia), those wonderfully old-fashioned terms that sound as if they divide us into two easily contained categories. We learn about astigmatism, that familiar What Can You See? 9 condition where the shape of the cornea causes light to be refracted improperly onto the retina. We learn about vision impairment and forms of blindness, in all their complicated variant states—loss of peripheral vision, the gaping hole in the visual field called macular degeneration, and the different ways in which we are affected by vision loss through age or accident or at birth. The eye, the most wonderful and complex of our sensory organs, is full of questions. As you face the eye chart, though, the doctor reduces all those questions to one: “What can you see?” So you start, row by row, until you reach the point at which the world’s edges drop away and the image dissolves into gray powder. In a moment, the doctor will ask you to read the next line, which is the line you cannot read, and the diagnostic moment will be reached. Of course, the eye chart is only one piece of the eye exam, and maybe not even the most important. What the doctor sees within the eyeball could result in tougher news. Looking inside the eye: that’s another secretive, internal medical procedure, and at best it can only be narrated to us. There are field tests to check the range of peripheral vision and tonometry to measure the fluid pressure within the eyeball. There are ways to measure the thickness and shape of the cornea and to check for retinal tears. There are procedures for determining the health of the optic nerve, and there are ways to evaluate the ghostly detritus called floaters that drift through the eyeball’s fluid center, crossing the visual field like a shoal of squid. Yet none of these diagnostic procedures has quite the mystery, and maybe the charm, of the eye chart on 10 eye chart Figure 1.1 Herman Snellen’s carte de visite. the other side of the examining room. Because the eye-chart part of the exam is something different, something out there, something slightly old-fashioned, something where you do the narrating yourself. Snellen died in 1908 at age seventy-three. Snellen’s carte de visite shows the doctor, probably in his last decade, with the eye chart in the lower right corner, as if it were his signature. In effect, it was. What Can You See? 11 12 2 Reading Stars, Reading Stones There was optical measurement long before there were optical instruments, and there were eyeglasses before there were eye charts. In Jewish tradition, the day begins at evening, and twilight is the critical boundary separating one yom from the next. Evening is the dark beginning of the new day, officially arriving when two stars can be seen. Today we can’t all easily see the stars, and earth is doing its best to screen out the heavens with light pollution. The pre-industrial desert peoples may have missed out on industrialized modernity but they had this advantage over us: skies were clearer. A commonplace in the history of visuality says that in the cloudless nights of the Arabian desert (the desert needn’t be Arabian, but the skies had to be cloud-free), a man’s keenness of sight could be measured by the rapidity with which he could distinguish two stars. Is it true? It’s true enough. The history of ocular measurement nicely marries precision to myth. Even today, amateur stargazers can test their ability to distinguish twin stars or find the bright fuzz of a nebula or every component of a constellation. To look up is to test one’s eyesight. Earlier cultures had simple magnifying tools. The Norsemen, the Romans, and surely the Egyptians before them deployed reading stones, polished hemispheres of a clear crystal mineral that a near sighted scribe might pass, delicately, across a manuscript, enjoying the benefits of at least of a little magnification. Such a magnifier acted as a simple lens. They must have taken care not to let the reading crystal touch the surface of parchment or papyrus. Even a well-polished reading stone might have damaged a fragile document. The word lens comes from Latin for “lentil.” The next time you hold a lentil between your fingers you can see the legume as a pair of convex lenses. There are lenses (not lentils) that date to antiquity, one of the oldest being the British Museum’s socalled Nimrud Lens, a three-thousand-year-old Neo-Assyrian disc of ground quartz, or maybe rock crystal. It’s about an inch and a half long. The British Museum describes it as “of little or no practical use” as an optical lens, but that hasn’t eliminated speculation that the Assyrians used lenses, including this one, in order to examine the world, or the cosmos, in detail greater than the unaided human eye would permit.1 The power of the lens to focus the sun’s rays is one of childhood’s first lessons in optics. It’s also one of the oldest. The Nimrud Lens might have been used to ignite kindling, but by the time Aristophanes is writing his comedies in fifth-century Athens, the everyday art of harnessing the sun with a lens pops 14 eye chart up as a plot device. In The Clouds, we hear about burning lenses from Sokrates himself. A character named Strepsiades is in debt, and hopes to have Sokrates train his son in argument so that a lawsuit may be won. But there might be another way: Strepsiades: Ooh, Sokrates, I’ve found a glorious bamboozle! I’ve got it! Admit it, it’s wonderful! Sokrates: Kindly expound it first. Strepsiades: Well, have you ever noticed in the druggists’ shops that beautiful stone, that transparent sort of glass that makes things burn? Sokrates: A magnifying glass, you mean? Strepsiades: That’s it. Well, suppose I’m holding one of these, and while the court secretary is recording my case, I stand way off, keeping the sun behind me, and scorch out every word of the charges. Sokrates: By the Graces, a magnificent Bamboozle!2 It’s a wicked plan—hold a lens at the proper angle, and the sun’s rays could be focused on the wax tablet on which the charge is registered. Strepsiades doesn’t follow through, but the exchange tells us that Athenian druggists knew how to use lenses to produce a heat source, at least on a sunny day. I like the fact that Sokrates and Strepsiades are talking about using the lens—something we bookish types consider one of the great achievements of technology—not to read or to see but to cheat. And not only to cheat but to cheat by melting a text, erasing it clean away. (A friend who studies cuneiform Reading Stars, Reading Stones 15 points to a longstanding professional rivalry in the study of the ancient world. The Greeks had better literature than the Assyrians, but the Greeks’ originals have been destroyed by fire and time, and all that remains are copies, sometimes error-filled copies of copies of copies. The Assyrians, on the other hand, didn’t leave us the great tragedies, but what we have are original documents, pressed into clay, baked and rebaked by fires that would have destroyed combustible papyrus, or vellum, much less wax tablets.) The ancients had another means of enlarging an image, and one that was less likely to melt or set fire to a document. At the beginning of the Christian era, the Roman philosopher Seneca mentions a method of magnification by filling a clear vessel with water and placing it between the viewer and the object to be studied. The next time you’re seated at a table with a candle, maybe in a nice restaurant, place the water glass between yourself and the flame and see the illumination increase. Now hold up the bill to the glass to see if service was included. Developing a means of testing the strength of a person’s vision sounds like a simple, progressive goal, beneficial to everyone who might need corrective lenses. A society where vision is understood to be correctable is also a society preparing itself for increased literacy. It would also benefit the lens makers, whose craft enabled them to produce polished glass and crystal for both ornamental and practical purposes. That one of the best-known manufacturers of vision products today is called LensCrafters connects the work of 16 eye chart contemporary optometry to the oldest, and insufficiently understood, art of polished stones. The premodern world had simple ways of enlarging images. In an age when anyone can order up contact lenses, we take for granted that before technological modernity people simply coped with visual limitations as best as they could. Can we know how well people could see in centuries past? There’s ample evidence—in the precision of miniatures and illuminated manuscripts, in the small typefaces of books printed for a broad reading audience—that Early Modern eyesight may have been even better than our own. It’s hard to make comparisons of sensory abilities across time, but some comparisons seem easier than others. It isn’t difficult to believe, for example, that Shakespeare's audience heard— listened—better than we do. In an era before recording, ears had more work to do. Audiences for Beethoven or Wagner in the nineteenth century had to pay better, closer attention to music that could only be heard live, and rarely at that. We can explain away our less attentive hearing. We punish our ears with headphones and loud noises, we force our ears to struggle with too much acoustic information and rely too easily on the recoverability of desirable sounds thanks to digital reproduction. But all that only adds up to evidence that we have unlearned to hear, even as we use hearing aids to collect more sensory data for auditory processing. Vision is different. It would be hard to argue that people see less well in the age of mechanical reproduction as a direct result of there being more things to see, or because the welter Reading Stars, Reading Stones 17 of technological messaging has dulled our capacity to make precise visual discriminations. Some people demonstrate extraordinary eyesight and visual skill. There are artisans of the miraculous who carve things like the figure of Napoleon in the eye of a needle. You can see such things—they’re called micro miniatures—at Culver City’s charming and strange Museum of Jurassic Technology, a modern cabinet of curiosities where “looking” takes on new meaning.3 Such miracles of sightededness, though, were created in the age of the microscope, a tool unavailable to a medieval manuscript illuminator who produced work all the more wondrous for the absence of modern optical tools. Medieval and Early Modern discussions of the eye are surprisingly numerous. There’s even one by a pope. The London College of Optometrists notes the historical jostling for rights to the first documented spectacles, concluding that the appliance was probably developed gradually over time.4 Ancient and medieval reading crystals notwithstanding, the move from a handheld magnifying object to an appliance worn on the face is the crucial transition to spectacles. The thirteenth-century magus Roger Bacon is only one of the medieval figures associated with the idea of eyeglasses, but all indicators point to Italy, sometime in the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century. The oldest extant depiction of eyeglasses in a surviving work of art appears in a fresco painted by Tommaso da Modena in Treviso, north of Venice, in 1352.5 As interior designers know, books make people look smart. Renaissance artists, commissioned to record an 18 eye chart aristocrat or scholar or successful merchant, knew this long before House Beautiful. Art history is always a good place to look for evidence of the real, even if it’s an idealized version of the real. You can wander through any museum and trace out the many ways in which reading is a principal activity of figures in Old Masters paintings. Religious subjects would be impoverished without the open book, sharing with the viewer some Biblical moment in which the painting’s subject is complicated with beautifully rendered codices. Secular portraits depicted readers, too, adding depth to the figure’s identity through the presence of readerly objects— correspondence, ledgers, scholarly work, music—that demonstrate the subject’s groundedness within the world of letters. Place a man (the subject was almost always male) alongside a pile of well-thumbed books and you’ve said volumes about his thoughtfulness and intelligence. Give a man eyeglasses and you’ve told the world how hard he studies. The scholar-saints, like Jerome and Ambrose, might be posed with a pair of glasses, either on the bridge of the nose or on a shelf. So might a successful merchant, scrutinizing a gold weight on a crowded desk. By the fifteenth century there were artisans grinding lenses and making frames to hold those lenses in place upon the face. Absent any rigorous metric for determining the strength of the client’s vision, the choice of eyeglasses would have depended on trial and error. Yet however difficult the process of finding the right lenses might have been, eyeglasses were emerging as useful, and even prized, Reading Stars, Reading Stones 19 objects: “Spectacles had broad currency among elites in Italy and elsewhere from the mid-fifteenth century on, serving not only as aids to vision but very correct gifts of courtly patronage and as status symbols,” writes D. Graham Burnett. “Moreover, understanding the needs of different customers had led lens craftsmen in Florence and Milan to codify the types of lenses available into graduated categories correlated to the user’s age, and hence to what would be understood today as myopic stages.”6 Those calibrations—market niches, really—are the beginning of what the eye chart would be testing for. Aside from portraits, we have few images of eyeglasses in the records of the Age of Discovery. There’s an early image of a man with eyeglasses in Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), and a fleeting account by one of Magellan’s crew to an encounter off Borneo. Upon being shown what the Europeans had carried with them halfway across the world, the islanders were most impressed, so the report goes, with iron and with eyeglasses. (Maybe: the word could be a mistranslation and may have meant “mirror” instead— “eyeglasses” isn’t a term for which the native language would have had an easy equivalent.7) It’s difficult not to connect the sixteenth century’s explosion of print materials and the Reformation’s validation of the vernacular with the development of reading aids. Compared to life a century earlier, the well-educated late sixteenth-century European had access to a vastly expanded range of reading matter. Broad reading was simple: all that was required was literacy, 20 eye chart fluency in several languages, a budget large enough to buy whatever books you wanted, a library in which to house them, and eyeglasses so that you could read the small print. E The early seventeenth century was a period of epochal advances in our understanding of vision and the developments of tools to expand what the natural eye could see. When he wasn’t busy revolutionizing our understanding of planetary motion, Johannes Kepler’s experiments with light led him to articulate an important principle of optometry: the reversal of the image upon the retina. And then there was Galileo. Galileo took earlier Dutch experiments with the telescope and trained a superior instrument on the night sky, discovering truths about the moon and the solar system, but at the same time demonstrating new capacities for human vision. The unfolding drama of seventeenth-century science is a series of discoveries and inventions, some of which transformed our understanding of visuality simply by showing that the eye could do what no one had imagined it could. In 1610, at the moment that Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius (The Starry Messenger), our eyes became more imposing organs of sight—ordinary eyes raised to a higher power. One of the great oh-to-have-been-there meetings in history occurred in 1636, when the poet John Milton, then twenty-eight, traveled to Italy and met the aging astronomer. Reading Stars, Reading Stones 21 Milton would remember the encounter with Galileo. In Book One of Paradise Lost, published thirty years later, the now-blind poet made an allusion to the “optic glass” of the “Tuscan artist.” In Book Three, Milton describes Satan landing on the edge of Paradise and coming upon a sight more dazzling than anything an astronomer might see through the “glazed Optick tube” of the telescope. For Milton, poetry triumphs even over telescopy, as poetic vision must triumph over even the greatest lens making. Beginning around 1674, the year of Milton’s death, the Dutch tradesman and lens maker Antonie van Leeuwenhoek put forward the results of his microscopic research, undoing assumptions about unicellular life as well as about the capacity of lenses to reveal the infinitely small world around (and within) us. Leeuwenhoek’s invention and discoveries went further: like Galileo before him, he was reinventing the eye by redefining its capacities. We could see more than we knew, as if unknown muscles had been discovered in the visual body. The practical needs of ordinary people and the celestial ambitions of astronomers converged in a need for more precise measurement and a better understanding of how well the eye might see. Precise measurement of visual acuity, however, would have to wait for more than a century and a half. 22 eye chart 3 How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) My father, whose eyesight was much better than mine, could go to the drug store to buy off-the-rack reading glasses. Mass production now makes it possible to standardize inexpensive glasses of different strengths, and what you find in one drug store will be the same in another. They’re not great, but they’re cheap and they’re calibrated, so if you don’t know which ones you need you might try on several until you find the one that works. You might find some sort of small eye chart there in the store, right between the hand sanitizer and the sugar-free gum. We’ve long had devices to help us test our own vision. Here’s one that was copyrighted in 1927, the year my father was born. You look through a little lens and move a tiny Snellen target along a balsa wood strip until you can see it clearly. The spot where the target lands is marked with a number corresponding to the lens strength you need. Figure 3.1 A 1920s optometer. Before the nineteenth-century revolution in standardized vision testing, you were pretty much consigned to trying on what you thought was best for you. There were shops offering a range of appliances, and before shops there were peddlers toting boxes of glasses. You chose what seemed to match your needs. Eye charts are a nineteenth-century invention. There was, however, a brilliant early attempt to test vision precisely. It didn’t go anywhere, but it’s one of the wonders of ophthalmological history. In 1623, the year that 24 eye chart Shakespeare’s colleagues created a posthumous collection of his plays in one large folio volume, an obscure Spanish monk published a remarkable guide to lenses and visual testing. The Uso de los antojos para todo genero de vistas (The Use of Eyeglasses for All Types of Vision) by Benito Daza de Valdés has been referred to as the Holy Grail of ophthalmology.1 We know little about Daza. He was born in Córdoba in 1591, became a Dominican friar and minor functionary of the Spanish Inquisition, and died in Seville in 1634. His name lingers in official histories of optometry and on the door of a Madrid optics institute, but Daza remains a distant figure.2 Daza’s book is as scarce as its author is remote; there are far fewer locatable copies of the Uso than there are of the Bard’s collected dramas. We have 235 copies of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, reports the Folger Shakespeare Library, while a count of the Uso made a dozen years ago turned up seventeen copies worldwide. One of those seventeen is in the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, which is where I was able to examine the real thing. If there were ophthalmological justice, historically speaking, the little book would be on a world tour of its own. The Uso explains how lenses work and why they’re shaped the way they are. There are chapters on blurred vision in the elderly, natural and acquired defects of the eye, the properties of convex and concave lenses, the best material for making glasses (rock crystal lenses are rated highest, though the celebrated Venetian glassblowers of Murano provide a pretty good alternative), and so on. We learn that How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 25 Madrid, Lisbon, Seville, and Rome are places you might have gone to buy your glasses, though peddlers were always available. Crucially, the Uso provides a sort of home test for determining what “degree” of lens the user might require. It’s basically an Early Modern textbook in optometry, and like other instructional publications of the seventeenth century, it delivers its valuables in several modes: through diagrams, explanatory passages, and dialogues. In the title of Daza’s book the word “antoios” (or antojos, the i and j being interchangeable) signifies the use of devices “before the eyes” [ante oculos]. Spectacles are crystals before the eyes, not implements to be held in the hand. It’s the difference between a magnifying glass and a pair of designer frames. Spectacles are appliances, detachable worn things, and their invention is a sign of what we might think of as optical modernity. In modern Spanish the term for spectacles in the sense of eyeglasses is anteojos, a word that preserves its Latin origins just a shade more visibly than the seventeenth-century antojos. In modern usage, on the other hand, the Spanish word antojos can be translated as fancy, or whim, or triviality. A restaurant might bring antojos before you order your dinner. Antojos—appetizers, amuse gueules, fancies—placed before you, and before your eyes, too. Compare the English word spectacle, which might mean some extravagant thing that requires attention—a play, for example. In the plural, spectacles could then be several extravagant things, or it could be a collective noun 26 eye chart identifying the thing through which one looks. A pair of spectacles might be handy for viewing a spectacle. In As You Like It, Jaques delivers Shakespeare’s famous “Seven Ages of Man” speech, and when he talks of physical decline, the age of “the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,” he notes that this is the age when man will have “spectacles on nose.” But when in Henry VI Part 2, the grieving queen Margaret curses her own eyes as “blind and dusky spectacles,” the playwright elides our distinction between the eye as an organ and the eye as a device, the thing that sees and the thing through which one might see. In The Winter’s Tale, the raving King Leontes, convinced that his wife is unfaithful, asserts that the good Camillo can see this as well, “or your eye-glass / Is thicker than a cuckold’s horn”—here eye-glass is the eye’s lens, or more exactly a lens rendered opaque by a cataract. Nowhere in the plays does Shakespeare speak of “eyeglasses” in the modern sense, but the word “crystals” does show up, and when it does it once again refers to one’s eyes. In the second act of Henry V, when the hostess reports the death of Falstaff, the fat knight’s former ensign Pistol tells the hostess that it’s time to “clear thy crystals”—stop crying— and say goodbye. E Daza’s Uso makes a spectacle of its subject. On the title page the printer has set the most wonderful device: a pair of eyeglasses, radiant with energy. Light seems to stream outward to four eyes placed in the corners of the rectangular How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 27 Figure 3.2 Uso de los antojos, title page. plate. It’s an image, suggestive of extromission, one of the prevailing theories of vision according to which sight was the result of the eye sending out rays that captured and retrieved the image of the thing viewed. In one lens is a brilliant anthropomorphic sun, and in the other sits the man in the moon. Lozenges with stylized concave and convex lenses 28 eye chart bracket the image. These eyes watch and are watched; the appliance sharpens vision by day or night. Other title pages of the period also envisioned light and vision as important symbols of the contents to follow. In 1626, three years after the Uso’s publication, Sir Francis Bacon’s Sylva Sylvarum, or a Natural History in Ten Centuries (meaning ten groups of one hundred entries) appeared in print. The popular volume was a collection of one thousand “experiments”—though they were more like thought experiments than laboratory protocols; the Scientific Revolution was just getting under way. The work has a famous title page showing the revelation of divine light, here the unspeakable Hebrew name of God, shining down so that mankind can see the world. In the seventeenth century the divine source of light had biblical, as well as astronomical, authority. Today another image of superhuman light passes through American hands in the form of the Great Seal of United States, one of the two engraved insets on the reverse of the dollar bill, with its Masonic eye looking down from a triangular eminence. “Annuit coeptis,” reads the motto. It isn’t easy to translate, which is one reason it hasn’t joined the short list of Latin phrases in popular culture. Annuit coeptis means something like “it favors undertakings,” where the shining eye of wisdom looks down kindly upon the actions of mankind below. Daza’s frontispiece engraving is different. Divine light is present (he’s a cleric, after all, and the book is dedicated to Our Lady), but the source of the radiance seems to be coming How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 29 Figure 3.3 Francis Bacon, Sylva Sylvarum, title page. from the spectacles. The light just might be within us. In the great age of the telescope and the microscope a good pair of eyeglasses makes discoverers of us all.3 We don’t know much about the origins of Daza’s text. An approval for publication is dated three years earlier in 1620, and the exclusive license for its sale expired in 1633, five years before the author’s death in 1638. There was no second edition in Spanish, and apparently no translation published 30 eye chart in English or any other European tongue, not even Latin, the tongue of tongues. A French translation, undertaken within a century of publication, survived in manuscript but was never published.4 So Daza’s book functionally disappears, but not because it was quickly superseded by more detailed or more accurate guides to lenses and visual acuity. The Uso is not only the first of its kind—it is its kind. There would be nothing like it, at least not until the mid-nineteenth century when Dutch, Austrian, and German physicians rewrote the book on eye measurement. So what does the Uso contain? In early seventeenthcentury Catholic Spain, one might expect that a text with Daza’s scientific ambitions might be subject to special scrutiny, but Daza passes with flying colors. The censor’s preface assures the reader that nothing here is contrary to Church doctrine and that the author’s style is suave, breue, y compendioso (smooth, succinct, and yet broad). Inside, Daza lays out the earliest printed diagrams for testing eyesight and offers a remarkable discussion of optical strength, weakness, and correction, sometimes in surprising detail. He takes pains to note, for example, the changing strength of vision in each decade of adult life, assigning a predictable degree of weakening for each ten-year period. He even notes, without prejudice, that women’s eyesight changes over the life course at a different rate than men’s. Whether or not modern diagnostic techniques would support such a view, it’s startling to encounter this straightforward empirical report of gender as a factor in predicting changes in visual acuity. How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 31 The Uso’s early eye charts, with their markings and numbers, almost look readable to us today: the scales, the graduation, the definitive starry punctuation—the graphic elements are startlingly confident. Writing simply and in the vernacular, Daza provided scales and diagrams that might work as self-tests, the way L.L.Bean has you trace your foot on a piece of paper to see what size boot you should order. The Uso includes an even simpler procedure: lining up several mustard seeds, spacing them according to instructions, and determining the point at which the viewer can no longer distinguish one tiny seed from the next. With Daza’s mustard seeds we’re somewhere between the twinned stars in the Arabian desert and the fuzzy bottom line of Snellen’s chart. Eye testing is always about the threshold. Historians of medicine have written about Daza,5 but from the perspective of cultural history, the most interesting part of the Uso is the concluding series of dialogues in which gentlemen discuss their eye conditions with experts. In a Figure 3.4 Testing image from Uso de los antojos. 32 eye chart Figure 3.5 Testing image from Uso de los antojos. passage noteworthy for its content and its casualness, we’re introduced to travelers Jorge and Esteban, dos caballeros indianos (two gentlemen from the Indies). At home they have seen a pair of eyeglasses of Spanish manufacture, and they have traveled across the ocean to have their eyes checked by a famous specialist. Jorge and Esteban become the premise for a dialogue concerning ways in which eyes are imperfect and how lenses can be crafted to compensate. Jorge, nearsighted since early childhood, has struggled with glasses in quite recognizable ways: his embarrassment at needing them, his wife’s advice that he shouldn’t wear them because they make him look old, the frustration of arriving at the theater and, having forgotten his glasses, being unable to see the performance. How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 33 Here at last, after his long journey, Jorge gets the professional help he seeks. Such an offhand demonstration of Atlantic cultural exchange in the early seventeenth century is startling: a voyage across the Atlantic from the Americas to Spain, purely for the purposes of professional eye care and the purchase of eyeglasses, is passed off to us as nothing particularly remarkable. The traveler who flies from Tokyo to New York to purchase a pair of designer frames today at Morgenthal Frederics or Robert Marc is hardly making an equivalent investment of time and effort. In another of the Uso’s narrative episodes, Daza presents the reader with the farsighted Señor Claudio, testing out a series of lenses. He discusses his options with a figure identified only as el Maestro—the Master—who patiently demonstrates his optometric expertise. Claudio and the Maestro progress through a battery of tests—without, of course, the benefit of split-lens refraction or other tools of modern-day diagnostics. Yet four hundred years have not changed the essence of the optician’s trade. The Maestro asks the question we could be hearing in a twenty-first-century examining room: “Better or worse?” Once it becomes clear that the stronger the glasses, the smaller the type he will be able to read, Claudio wants the strongest lenses possible. But the Maestro demurs. People go blind, he cautions, trying to train their eyes to see more and more precisely. The reproof is more than a concern for the patient’s eyestrain; in the early seventeenth century the prevailing philosophy of optical correction encouraged the 34 eye chart use of weaker and weaker glasses so that the eye would—at least in theory—gradually increase in strength. Eyeglasses were critical to reading, but as Daza’s text shows, they weren’t functional only in the sense of increasing one’s ability to apprehend the world. Eyeglasses performed an important social function. Daza gamely makes his point through the introduction of yet one more optometric straw man. Enter Marcelo who, with his corrected vision, can at last describe himself as señor de todo que lo veo. Lord of everything I see, he exclaims with delight. A later and more memorable version of that idea is the phrase “monarch of all I survey”—which, by the way, is not without irony. It comes from “The Solitude of Alexander Selkirk,” an eighteenthcentury poem by William Cowper. Selkirk, famous for having been marooned on a South Seas island, became an inspiration for Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. So much for range of vision. Marcelo’s story tells us something about accurate sight not only as a practical matter of biological survival but as tool for both social and political engagement. Eyeglasses were becoming socially necessary because it’s impossible to behave properly if you can’t see properly. Vision correction morphs into a mechanism for social correction, which in turn is about self-development and social mastery. And so the Uso explains how nearsightedness can lead to social difficulties. Marcelo’s most embarrassing moment: It happens that (for my sins) I must have been born nearsighted, and I never noticed this fault so much as I How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 35 do now, when it afflicts me especially, as it undercuts all the pleasure and exercise I take in going out of doors, as you know, and I swear that I can’t even see the game that my feet flush up. The same occurs with many people that I encounter on the street, about whom I make such mistakes that on occasion some of my friends believe I deliberately don’t remove my cap for them. That’s why—more often than not—I take it off without knowing whom I am taking it off to, which violates the rules of social decorum. And as a result of this politeness, an awful thing happened to me while I was a student in Salamanca, which I remember to this day: as I was walking down a street, I took off my cap to a lady who was at her window, and as I saw that my servants began to laugh at me, I asked them who that person was, and they answered that it was a side of mutton that had been hung up. I blessed myself and made a thousand signs of the cross, for I would have sworn that I’d seen her, with all her veils and all her features. But all this aside, I can see on the other hand that when I look at something close up I’m a lynx, and there’s no letter, no matter how small, that can hide from me: even at night, by moonlight, I can see and read very well. I’m amazed at these two extremes, and I don’t know what to make of it myself.6 Marcelo’s embarrassing encounter with a sheep carcass brings us face to face with a world where social rules count. Daza writes that Marcelo is pervirtiendo las cortesias (perverting 36 eye chart the order of courtesies), undermining the social order and the ideologies that protect it through sumptuary laws and other ritual displays of status. Marcelo needs eyeglasses so that he can tell a doña from a criada, a lady from her servant. Or from a side of mutton. Marcelo and Claudio, the one nearsighted and the other farsighted, propose traveling together, having discovered, like all odd couples from Plato to Neil Simon, that their conditions are complementary. In the Symposium, Plato has Aristophanes expound fancifully on the nature of love, which he does by recounting a myth of human origins that depends on incomplete figures searching for their completing, complementary other halves. Shakespeare, following the Roman comedy of Plautus, picked up the trope in The Comedy of Errors, where not one but two pairs of twins reunite and complete themselves. Marcelo and Claudio are optical twins, or at least optical opposites constructed for educational purposes. Here convex and concave are complementary variations that not only correct us into normality but also make us complete. When mid-twentiethcentury men referred to their wives as their “better halves” (the phrase is, I think, now safely on the shelf) they were unknowingly a part of a 2500-year-old theory of love and unity. E What might we take away from the adventures of Daza’s optometric straw men? First, that people in the Early Modern How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 37 European and Atlantic world worried about their vision, fussed over the choice of eyeglasses, and might even have traveled thousands of miles to be tended by highly regarded professionals. Daza’s attempts to regularize a protocol speak to the absence of a reliable system of visual measurement. As to social control, Daza’s lessons make eyeglasses part of the citizen’s responsibility not only to the self but also to a hierarchical society. To a cultural materialist, the ability to resemble one’s social betters is more than dress-up; the gesture peeks behind the curtain of social systems, and when it looks there it finds the essential artifice of class busily adjusting the rules to maintain itself. A cat may look at a king, and a wealthy middle-class cat can dress like one, too, and that becomes a problem. What you wear—how you look—can be a deception. It’s in this period that the highwayman and the pickpocket step onto the literary stage, characters ready to delight readers with stories of trickery and theft. The swindler and the thief, the fraud, the man or woman who pretends—through the sign-system of clothing—to be what he or she isn’t—all demonstrate the pleasures and dangers of deception. In sixteenth-century England, the Tudors, alarmed by the economic success of non-aristocrats, enforced sumptuary laws, issued decrees that banned all but royals from wearing purple silk, gold tissue, or sable, even if a sixteenth-century fashion plate could afford such things. In 1623, Philip IV of Spain cracked down on sumptuary violations. There should be no social misreading. Eyeglasses might help. 38 eye chart Perhaps Galileo’s telescope, like Newton’s later in the century, was from a lensmaker’s perspective only one more antojo, something else to be placed before the eyes so that powers of vision could be heightened beyond their natural capacity. But the telescope and the pair of spectacles work different changes on the sensorium: the telescope, like Hooke’s microscope, is an invention of the exceptional, a mechanism that exploits the endless appetite for greater visual acuity, moving the viewer deeper and deeper into the visual field. Eyeglasses, on the other hand, are inventions of the normal. They exist to make possible integration of the visually impaired into the realm of the social. How Early Moderns understood deficiencies in vision, and how they invented means of overcoming those deficiencies, is part not only of the history of medicine and technology. It’s part of the invention of the self-regulating individual, the subject newly equipped with metrics for daily living, whose experience, for better or for worse, is part of what we mean by “becoming modern.” Only a part of Daza’s book concerns testing visual acuity, but that small part inched us toward the professional evaluation and prescription that early nineteenth-century ophthalmologists would make their project. How to Choose Eyeglasses (circa 1623) 39 40 4 The Persistence of Memory In the scientific seventeenth century, the lens became an object of extraordinary importance, perhaps less so in terms of eyeglasses than for the development of the telescope. The history of telescope making even has a curious connection to the document we know as the Snellen chart. Though the Dutch are credited with the first Early Modern telescopes, the focus of action soon moved to Italy. In the decades following Galileo’s death in 1642 (the year that, as fate would have it, Isaac Newton was born), Italian telescope makers went from strength to strength, competing with one another to produce the strongest and most accurate instruments in all Europe. Among the distinguishing features of late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian intellectual life was the prominence of the accademia, a confraternity (or academy) whose members devoted themselves to intellectual pursuits. Among the most prominent of these organizations was the Accademia dei Lincei (the academy of the lynxes), so called because their eyesight (or their intellectual perspicuity) was remarkable, at least by their own account. Galileo was admitted as a member in 1611. Another organization, the Accademia del Cimento, predated England’s Royal Society and became the first European organization to devote itself to experimentation. The Accademia del Cimento lasted only for a single decade, from 1657 to 1667, but in that time one of its concerns was the rivalry between two optical inventors, Eustachio Divini and Giuseppe Campani. Among the most prominent figures in the European network of optical researchers and manufacturers, Eustachio Divini was born in 1610 and studied under a student of Galileo’s. Beginning his professional life as a maker of clocks, Divini soon took up the art of lens making. By 1646, he was manufacturing compound microscopes and telescopes, producing instruments that were admired and collected. Several still exist today. Giuseppe Campani, twenty-five years his junior, was also recognized as an outstanding manufacturer of telescopes, some of which were as much as fifty feet long. The rivalry between Divini and Campani reached its climax in 1660 in an extraordinary field test. How to compare telescopes? A sort of telescopic duel was devised, but a duel with an interesting twist: one telescope would be set up in Rome, the other in Florence. The telescopes were separately examined and judged on their individual merits, but it was decided that they had to be tested together; the object was to be a point not in the sky but on land.1 It being 42 eye chart easier to transport a test document than a telescope, it was in theory possible to test different instruments in different locations and compare the results. The question remained how one might accurately measure the comparable power and precision of two different optical instruments in two distant locations. It was proposed that the instruments be directed at a page of graduated text mocked up expressly for this purpose and positioned at a point equidistant from both telescopes. The results, however, were not conclusive. There were disagreements on how close to the test sheet assistants were to hold the lamps. Arguments ensued about the relative purity of the air in Rome and Florence and its effect on visibility. Most important, the telescopes had been tested by different observers, men whose own degrees of visual acuity would result in different interpretations of the telescope’s image.2 There was another handicap in the 1660 tests, too, and this one was literary. The test sheet—the page on which the ocular devices were trained—was composed not of random symbols or even of single words but of lines of poetry. What were the literary passages? Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita (In the middle of the journey of our life)—the first line of Dante’s Commedia. Voi ch’ascoltate in rime sparse il suono (You who hear the sound in scattered rhymes)—the first line of Petrarch’s great volume of sonnets.3 (Imagine asking an American patient to read all of a line that begins “Oh, say can you see . . .” or a Briton asked to read out a line that began The Persistence of Memory 43 “Land of hope and . . .” It wouldn’t be hard to get a positive result.) Given the terms of the protocol, the telescope viewed by an educated viewer could be judged the finer instrument. So in its first attempt, the “duel of the telescopes” failed. The Accademia realized its error and subsequently produced test forms utilizing nonsense words in place of classic Tuscan. The model of a competition for testing telescopes had been established, and “the competition between these masters even led to a tradition of public trials known as paragoni, in which the telescopes or objective lenses of master craftsmen would be set up beside one another and trained on some distant writing or object, in order to compare clarity and resolving power. In proposing a non-signifying series of letters, the Accademia del Cimento was two hundred years ahead of Herman Snellen’s chart.4 Poetry gave way to nonsense as science outweighed literary patrimony, but all in a good cause. The case of the dueling telescopes is a reminder of a fundamental principle on which eye charts, including the Snellen chart and its graphic descendants, are based: testing the ability to see depends upon disabling the ability to read. The good eye chart should not make sense in order to get our attention. A variant on the practice was long a feature of the modern publishing industry, where word-like sequences of letters, or sentence-like sequences of words, were paced along text lines to craft what’s called dummy copy. The point is to create a visual pattern, not to create meaningful text. Here the objective isn’t to test visual strength but to judge the effect of 44 eye chart a text block within a preliminary overall design. A designer producing this sort of work might sometimes be said to be “Greeking type,” filling out the measure of a sample text block with meaningless words (though if any language other than English were to be used for dummy type it would be Latin, and certainly not Greek). The most famous example of sample type is the notorious “Lorem ipsum” passage. It begins thus: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Quisque ultricies justo eu lorem scelerisque, eget porta ligula porta. Etiam sollicitudin diam dolor, a bibendum orci commodo id. Vestibulum dignissim pulvinar risus, a commodo est posuere in But the “Lorem ipsum” text isn’t really a text at all. It’s Latin gibberish (or Latinish gibber). There’s no such thing as a Lorem, except maybe in Dr. Seuss. What we do have here, though, are Latin words, or parts of them, or fragments of parts, complete with cases and declensions. But this still isn’t genuine Latin. Or rather it’s a genuine unreadable text. Latin looks different than English. There are fewer ascenders and descenders in Latin letters, so that the type as set has what a type designer would call a different “texture.” Even fake Latin can have that texture. From a purely typographic perspective, there’s nothing wrong with fake Latin. It’s a content-free dispersal of textual elements intended to show a designer, or a client, the The Persistence of Memory 45 effect of font, size, leading, and margins. It’s meant to be unreadable but not distractingly unreadable, as it would be if, say, the space were fitted out with emojis or unicode box drawings. So where did lorem ipsum come from? The mystery was solved by Dr. Richard McClintock, who located those two words to a single page of the 1914 Loeb Classics edition of Cicero’s De finibus bonorum et malorum (On the Ends of Good and Evil), where the word dolorem is split—do- is on one page and lorem on the turn. So someone, possibly in the 1960s, came across a 1914 copy of a Loeb Cicero, opened it, turned to this one particular page, found a series of letters, took some, scrambled others, and produced the most famous non-Latin text no Roman ever read. Despite its specific intent, the so-called lorem ipsum passage has migrated from type samples to embroidered samplers, presumably under the assumption that the garbled “text” is a genuine quotation from the antique. A few years ago I came across lorem ipsum needlepoint pillows (in learned Cambridge, England, of all places). You can buy lorem ipsum T-shirts and stickers on line, most of which are clearly in on the joke. E A century after Daza, English preachers could turn to vision care as a metaphor for care of the soul. In 1716, the vicar of Barton, Lincolnshire could warn his congregation about the 46 eye chart Figure 4.1 A sermon can test eyes, too. moral dangers of bad eyesight. “A Discovery of the Snake in the Grass: or a Spectacle for Weak Eyes” urges the listener to consider the Gospel as the pair of spectacles we all need so that we can avoid sin. In this case one size fits all. No eye chart needed. Did eighteenth-century optometrists devise any better way to select lenses for their patients than the trial and error The Persistence of Memory 47 that had guided purchasers for two centuries? Or did they take with them trade secrets we have yet to uncover? We have some evidence that eighteenth-century optometrics would share the views of Daza’s Maestro in matters of lens strength. In his Essay on Vision, the eighteenth-century English optician George Adams wrote that “the discovery of optical instruments may be esteemed among the most noble, as well as among the most useful gifts, which the Supreme Artist hath conferred on man.”5 As to strength, however, Adams argues that spectacles are overused, and that the purpose of having them is to bring one’s weakened eyesight into conformity with its natural ability rather than simply to make one’s eyes stronger. Adams is a practitioner as well as a theorist, and the Essay provides glimpses of what it was like for the eighteenth-century client to shop for corrective lenses. The picture Adams paints is of the customer trying out lens after lens, and falling into a sort of confused exhaustion from the effort, with the result that the brain stops judging accurately and the client further weakens the eyes. Adams’s opinion is an extension of the seventeenth-century view that the goal of eyeglasses is secondarily to enable reading and primarily to strengthen the eye and thus rendering the use of glasses unnecessary. The matter of how to test precisely for vision strength, however, remained unresolved into the nineteenth century. Like many successful inventions, Snellen’s eye chart followed earlier, less economical work by others. In 48 eye chart the mid-1830s, the German ophthalmologist Heinrich Küchler proposed a chart to test his patient’s eyes, using images of common things he had cut out of illustrated calendars.6 Then Küchler had an insight that was also a linguistic breakthrough: in 1843 he composed a chart that abandoned objects for words, which he stacked one on top of the other, in descending order of size. One of Küchler objectives was to help doctors treating those who were losing their sight, those “whose visual ability the physician wishes to measure and, in the interest of curing, must measure.”7 Here’s an image of Küchler chart—three, in fact. Figure 4.2 The Küchler chart. The Persistence of Memory 49 In English the first five lines would read The familiar descent from large type to small points ahead to the Snellen chart—the strong, clear figure at the top, and then the infinity fade. Even on their own, there’s something strange and compelling about the Küchler charts, with their singular nouns and German place names, all tricked out in upper- and lowercase German Fraktur typeface. Küchler’s three panels suggest that he acknowledged the problem of memory, and that he wanted the patient to work fresh, not from the recollection of what had just been shown. In finding his materials in random printed sources, Küchler was doing what would become a principle of European avant-garde art almost a century later. Cutting out pictures and words from newspapers, Küchler’s diagnostic project feels like a forerunner of Modernism: Dada’s language games, Duchamp’s celebration of the readymade, Hannah Höch’s bouquet of eyes, and the dueling collages of Braque and Picasso, who incorporated or reproduced elements of newspaper text into their compositions. Kidnappers, of course, would use the same tools to produce ransom notes. 50 eye chart Even after abandoning images of things and turning to words, Küchler testing device was still a very thing-y diagnostic, asking the person being examined to see mainly the names of objects that themselves could be seen. Of the first five lines, only the words Reich (empire) and Fünfzig (fifty) are conceptual, but even they don’t feel very conceptual in this company. Still, there’s a poetic quality to Küchler charts, and something of the kindergarten room, too. Looking at his very German selection of terms, it’s easy to think of other possible entries for a word-based eye chart. A more humble selection of nouns, for example, presented without graduated sizes, that would locate young readers in a lexicon of reading primers—Ball, Cat, Mother, House, Tree—the sort of display that would introduce early readers of the Dick and Jane 1950s to the visual signs for the nouns that make up their world. Despite his efforts to make multiple tests, the problem with Küchler’s eye chart is a problem that has always dogged tests for visual accuracy: words and other familiar objects offer too many clues, and on the basis of those clues the patient can fill in the blanks. It isn’t easy to outwit the determined cheat. Memorization is a flaw in all stable eye charts—prior access or a commitment to retaining what one sees becomes a way of gaming the visual system. It’s the same problem that plagued that first competition between Divini and Campani in seventeenth-century Italy. If you know the word Mother but you can only see the letters M O T H E it probably doesn’t make any difference if you The Persistence of Memory 51 can’t decide whether the last letter is an R or a P. You’ll guess the word, and that defeats the purpose of the test. The eye chart needs unfamiliarity to be effective, and unfamiliarity can be hard to sustain. The generation after Küchler advanced the ideas he had developed to make fundamental breakthroughs in visual testing. Prominent among them was Franciscus Donders. In 1858, the year he established his eye hospital, Donders was working through important ophthalmological research, including studies of vision and reaction time. He had ideas about how eye charts could work better, ideas he passed along to his assistant, Herman Snellen. Building on the work of Donders and others, Snellen developed his famous diagram, the graphic breakthrough of nineteenth-century ophthalmology, which is the eye chart we know. E As useful as the eye chart would prove to be, the century’s most important mechanical device for examining the eye was the invention of the ophthalmoscope in 1851 by the brilliant young German physician Hermann von Helmholtz. Helmholtz was interested in everything—philosophy, the conservation of energy, the mechanics of visual examination, thermodynamics—and made contributions to all these fields. At the age of thirty he revolutionized ophthalmological practice: by means of an ingenious arrangement of mirrors, Helmholtz’s ophthalmoscope permitted the physician to look through the dilated pupil into the back, or fundus, of 52 eye chart the eye. For the first time it was possible to observe directly the retina and the base of the optic nerve. The eye was made visible in a new and powerful way. Few examples of Helmholtz’s original ophthalmoscopes survive, but the device your doctor uses today is a modern updating of the nineteenth-century tool that changed how eyes could be examined. It is in the nature of things that we take the ophthalmoscope (and most medical devices) for granted, but in its capacity to make the invisible visible, Helmholtz’s invention was compared to another groundbreaking, and more familiar, medical device: the stethoscope. The word stethoscope is a neologism from the Greek meaning “to see the chest.” Invented in 1819 by the French physician René Laennec, the stethoscope is the medical tool that, as Michel Meulders writes, made audible what was invisible.8 It’s worth noting that the history of medicine is charged with episodes, inventions, and discoveries that allow us to see (or hear) what cannot be seen with the naked eye. The ophthalmoscope was one of them. Together with the eye chart, the eye exam had two powerful tools for assessing vision. The problem of memory would linger in eye chart design, challenging the ingenuity of inventors, graphic designers, and medical professionals. One solution, a revolving drum with flat panels of diagnostic images on each side, was in use by 1906.9 Optometry would struggle with the problem of repetition and memory until computerization, when it became possible to adjust instantly the letters or other figures placed before the viewer.10 In the digital present, the The Persistence of Memory 53 familiar Snellen arrangement and its many variants could be reformatted or replaced with the speed and facility we now take everywhere for granted. If there was long a concern that Snellen’s eye chart might be memorized, the emergence of advanced technological solutions may mean that Snellen’s diagnostic chart is already become an historical artifact, the founding document in how we understood modern visual testing and, like many founding documents, an object receding from view. The Snellen chart might be a thing we want to remember after all. 54 eye chart 5 Eleven Lines, Nine Letters The mid-nineteenth century has been called ophthalmology’s Golden Age. In Utrecht, Donders was making groundbreaking discoveries—“with a clearness and precision without parallel,” wrote an admiring contemporary1—concerning refraction, the changes affecting a light wave as it passes through different mediums (like the liquid within the eyeball), and accommodation, the mechanisms by which the eye alters the shape of the lens in order to focus on a close or distant object. The problems of reliable visual measurement were several: mechanics, ease of administration, possible memorization of the testing materials, and above all standardization, accuracy, and reproducibility. Following Küchler and others, Snellen’s early experiments with eye chart design involved shapes, but shapes were difficult for the observer to describe. Then in 1862 he hit upon his breakthrough graphic: eleven lines, clear type, nine alphabetic forms distributed in an apparently random fashion, reduction in size from top to bottom. Letters were, after all, shapes, too, but they were shapes most people could recognize. The following year, Snellen had what would prove to be the eye chart’s big break: the British Army took up his chart to test its recruits. In the Victorian era, the military objective of visual testing was to ensure that a recruit could fire a rifle and hit a target. With Snellen’s chart, the British military could study scientifically which potential recruits could be entrusted with firearms. Almost overnight, there was a reliable tool for measuring the accuracy of a recruit’s vision. If all the men who wanted to join up had been literate, Snellen’s chart might have been a complete success as designed. But they weren’t and it wasn’t. An Army Medical Report for 1887 found that 9 percent “of the recruits that sought enlistment” were “unable to read.” It’s one thing to have difficulty reading; it’s another not to be able to identify individual letters. The Snellen chart had to be modified with the introduction of test dots. During the examination, the subject would be asked to count the number of dots within a specific area at a specified distance. It was hardly satisfactory—even the Surgeon-General, who had requested this variation on the Snellen chart, thought that if “all recruits could read, it would be far better to use types of definite sizes, such as Snellen’s, for the examination of vision.”2 Dots were, at least temporarily, a necessary compromise. Despite military claims to rigor, standards for visual acuity in the armed forces have probably always been flexible. In 1914, a military report could declare that 56 EYE CHART “Candidates for naval cadetships must possess full normal vision as determined by Snellen’s tests, each eye being separately examined,” while in the case of other branches of the Royal Navy “full normal vision is not required.” Normal vision here is uncorrected vision, which is to say that Navy recruits could wear corrective lenses but would be ineligible for cadetships. The report goes on to offer, in elaborate detail, the levels of visual impairment permissible—and to which degree for which positions—throughout the Empire: the Royal Irish Constabulary, the Indian Pilot Service, the Department of Forestry, and on and on. For each, the military machine of the Edwardian era specified how well you would have to be able to see to get and keep that particular appointment. A special emphasis is placed on color blindness, and which positions would be unavailable to the color-blind candidate. There is even something called the “Colour-Ignorance Test”: “The object of this test is simply to ascertain whether the candidate knows the names of the three colours, red, green and white, and the test is to be confined to the naming of colours.”3 No positions are specified for which being “colouraware” would be a requirement. The British Army became the largest and most important early client for Snellen’s chart, and the military collaboration laid the ground for recruit testing worldwide. The military need for accurate visual discrimination would, in fact, play an important role in the creation of another test. In the midst of the First World War, the Japanese government supported Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 57 the work of Shinobu Ishihara, an ophthalmologist who had studied in both Tokyo and Europe. Like the British, the Japanese army needed a tool to determine the accuracy of color perception. The focus of Ishihara’s test for color blindness would be the ability to distinguish two colors that looked very much alike but weren’t, colors that were pseudo-isochromatic (or “only apparently the same colors”). Building on earlier tests for pseudo-isochromatism, Ishihara developed the kernel of our modern color blindness exam: disks containing colored circles of varying size and tones arranged to surround a figure (usually an Arabic number) in a slightly different color. The inability to see a green number amid a field of red circles or a blue number amid a field of green indicates a particular form of visual impairment. Color blindness is a sex-linked disorder, carried on the X chromosome, and significantly more prevalent in men than in women. The National Institutes of Health estimate that up to 8% of northern European males (and 0.5% females) may be color-blind.4 Snellen presented the patient with a single chart across which letter forms were strategically arranged. Ishihara’s color blindness test provided a single, artfully concealed image. Where the pre-digital Snellen test presents the patient with all materials at once, the Ishihara test shows the patient one single image after another. A century after its first publication in 1917, the Ishihara test remains a significant diagnostic tool. 58 EYE CHART E As a graphic, the Snellen chart is more than a diagnostic tool. It’s an event—confident, hierarchical—a display with stars and corps, a défilé, a fashion show, a march, with that great E at the head of the visual parade, followed by ranks in descending order.5 If this were the military, they would be colonels and majors, captains and lieutenants and sergeants. If E were God, the rows of descending letters would be thrones, dominions, and powers. But E is not God. God is in the details. The Snellen chart steps down in smaller and smaller type, until it finally gets down to business. Two things you’re likely to know about the Snellen eye chart: there’s an enormous letter E at the top (you’ve already found it throughout this text as a dingbat where you might have expected an asterisk instead), and so-called “perfect vision” is 20/20. The ratio 20/20 is often called the Snellen fraction, about which more in a moment. (In metric measure, 20/20 is notated as 6/6, a ratio that never sounds quite the same.) The term developed its own cultural life. The name of the long-running ABC news magazine 20/20 acknowledges this ideal of “perfect” vision, and also manages to suggest that perfect sight is balanced, favoring neither left nor right (eye or political view). Recently, colleges have taken up the shout of 20/20 as a way to brand their institutional vision (colleges, now following the battle cry of corporations, are all about vision and vision statements).6 Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 59 This common usage aside, we are likely to confuse 20/20—a base standard for good vision—with “perfect” vision (whatever that would be). Maybe it’s the implicit mathematics—20 over 20 being read as a unity, a resolution to 1—that encourages a popular belief that 20/20 is not only goal but both ideal and normal (as if the normal and the ideal have ever meant the same thing). The distinction between normal and common, or standard, affects vision measurement as it affects everything else in our lives (Dorothy Parker once quipped that heterosexuality isn’t normal, it’s just common). In establishing his 20/20 paradigm, Snellen was identifying a standard metric, not offering a scientific judgment on normal and abnormal vision. The standard eye chart devised by Snellen is composed of eleven lines. In most formats, the top line is a single letter. Each subsequent line is smaller, each designed to indicate a specific visual acuity, which also means a specific visual deficit. Snellen devised his test to measure the actual viewer (you) against an ideal viewer. In fractional notation, the top line of the eye chart would be 20/200, which indicates that the viewer has to be twenty feet away to see clearly something that Mr. or Ms. 20/20 can see at two hundred feet. If the top line of the Snellen chart is the only thing you can see with corrective lenses then your Snellen fraction is 20/200, and at least in the United States, you’re considered legally blind. Snellen’s second line is 20/100—the patient has to be twenty feet away from an object that the ideal 20/20 viewer can see at 100 feet, or five times that distance. The third line 60 EYE CHART is 20/70, the fourth 20/50, the fifth 20/40, the sixth 20/30, the seventh 20/25, the eighth 20/20. If you can read the eighth line down with corrective lenses, you’re at the 20/20 level. Line nine indicates 20/15 vision: the viewer can see clearly at twenty feet what the 20/20 viewer needs fifteen feet to see. Line ten is 20/13, line eleven 20/10. The rare set of eyes that can see clearly at 20/10 sounds like a miracle of nature, but the animal kingdom—from eagles to insects—outdoes us in many visual ways, so however good your vision is, it’s only good human vision. Understanding the fraction itself requires a bit of physics. The numerator represents the distance from the object. That’s easy: six feet, twenty feet, and so on. The denominator is trickier: it’s the distance at which the viewer can see an object measured at five minutes of arc. What is a minute of arc? Think of what you can see when you look straight ahead as a portion of a circle. That’s your field of view. Unless you’re a cartoon character, you live in three dimensions and in a given plane you stand in the center of 360 degrees. But your field of view is only 114 degrees. Whatever you can see—no matter how large or small, how near or far—can be measured in terms of degrees of visual angle. Hold your arm out in front of you. A little finger will measure a visual angle of about one degree of arc. Three middle fingers measure about five degrees of arc. Each degree can be further divided into minutes of arc, which is a sixtieth of a minute. (By the way, we can thank the Babylonians for all this “sixty” business—the division of Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 61 the hour into sixty minutes and sixty seconds. There’s a long dotted line from Hammurabi, four thousand years ago, to your most recent eye exam.) The denominator of the Snellen fraction sets as its visual goal a letter measured at five minutes of arc. It doesn’t make any difference how large the letter “actually” is—it’s the angle at which the image of the letter passes into the eye. (Walk toward a distant tree and it looks larger. The tree stays the same size, but its visual angle increases as it takes up a larger and larger proportion of your field of vision. That’s the optical principle at work.) Snellen represented the relationship of viewer, distance, and eyesight in this formula: υ= d D In this equation, v is the acuity of vision, d is the distance from the eye chart, and D is the distance at which the viewer can read an object at five minutes of arc. Many eye charts include annotations either in the left margin or the right or both, and each says something about what the lines mean. Along the side of some charts you might find a column of fractions; the most important is the one everybody knows—the optometric notation 20/20, which indicates that the viewer can see at twenty feet what is expected of a person with good eyesight. Your eye doctor marks out your prescription in a formula unfamiliar to most people who wear glasses or contact 62 EYE CHART lenses. Vision professionals measure the degree of correction required in diopters, a unit of measurement you’re not likely to encounter in any other circumstance. The dictionary definition of diopter: “a unit of measurement of the refractive power of lenses equal to the reciprocal of the focal length in meters.”7 In simple terms, a diopter is a unit of measurement indicating the power of the lens necessary to bring the eye’s vision to the 20/20 standard. If you look at the prescription you’re handed after an eye exam, you’ll see three columns crossed with two rows, and in those boxes are numbers—single digits marked plus or minus. The diopter correction needed in a lens is indicated by a positive number for nearsightedness and a negative number for farsightedness. For example, a moderately nearsighted eye might be prescribed a lens corrected at -3.0, or three diopters, while a severely nearsighted eye might require -5.0, or five diopters. Correction for mild farsightedness might be indicated by, say, +1.0 diopters. These corrections are indicated separately, first for one eye, then the other. The eye chart doesn’t really examine your eyes—it examines each eye, and your doctor records the correction necessary. Your prescription will have information for two forms of correction, either spherical or cylindrical. The spherical number gives information about eye strength and indicates the diopters needed for the eye in all directions. The cylindrical number gives information about astigmatism and indicates the diopters needed for the eye along a particular Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 63 axis. A third column provides further information on the orientation of the correction. E An eye chart doesn’t tell the doctor everything about your eyes, but it shows where things get blurry. It’s a common misconception that the test for visual acuity is simply about determining what degree of magnification is necessary, but the vision test is concerned not only with magnification but also with blurriness and sharpness of focus. Blur is a critical concept in visual correction—it’s where the patient’s vision becomes blurry that the eye chart is doing its work. Snellen thought about blur when he chose his elements—eleven lines of type and only nine letters—F D O C E P T Z L. Two vowels, seven consonants. If you knew this, you wouldn’t guess Y or R or H. Those letters, always the same letters. There are languages with almost as restricted a set of terms. Hawaiian, for example, has only thirteen alphabetic letters (plus two non-alphabetic markers). But Snellen’s nine letters are like the alphabet of a lost and imposingly severe language: what can they spell? Each line of letters seems deliberately constructed to avoid sequences that might be read as phonemes. At the same time, Snellen’s selection of letters has to present the viewer with shapes that are sufficiently similar to invite misidentification. Choosing between, say, an X and an O would be a lot easier, and tell the examiner very little about the patient’s vision. O and C are more of a challenge. Snellen’s letters are both 64 EYE CHART specific and intentionally ambiguous, moving not only downward into smaller and smaller point sizes but moving into each other’s shape-space, too. Isn’t the O the uncanny C? The F the uncanny P? The wholesome distinction between X and O has given way to something subtler, something as anxiety-provoking as modernity And by the way, what were Freud’s eye examinations like? Perhaps the most important, and surely the least commonly known, feature of Snellen’s chart isn’t the size or arrangement of the letter forms—it’s the disposition of the letters themselves. Each letter is of equal width and height. Snellen devised a chart with letters that could be mapped onto a grid, as if each letter sat within an invisible box. It’s hardly the most elegant solution to typographic design, but Snellen believed that it equalized the letters, that it would make the test’s results more reliable, and that it lent their form a scientific authority. Unlike Jaeger’s test-types, Snellen’s optotypes are built on an architectural model ensuring that the body of the letter form has amplitude, filling out the space of the grid in all directions.8 The gridded architecture of Snellen’s letters— in their early design in the Egyptian style and later on in their cleaner, sans serif forms—provided more dependable readings. With all strokes of equal weight, the examiner could discount the possibility that blurred perception was the result of a narrow letter stroke. If the letters on the modern eye chart look sort of oldfashioned, it’s partly because of that amplitude. Still, today’s chart letters are stylish compared to Snellen’s originals. The Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 65 first optotypi were designed in a style called Egyptian, a term that is sometimes used to describe a class of typefaces sharing certain design features, in particular the heavy— or “slab”—serifs. An early eye chart set in “Egyptian” uses letters outside the Snellen alphabetic canon (a B, an N), evidence of the immediate variants on the prescribed arrangement but showing the insistent griddedness of the Snellen formula. The Egyptian face was developed during the long nineteenth-century fascination with Egyptomania, a heady mixture of colonialism, anthropology, and philology. To modern eyes, Snellen’s Egyptian Paragon is all about serifs. If you look at it the right way, you can see in the serifed letters the flat figuration of the human form as it appears in Egyptian hieroglyphs. Egyptian Paragon looks kitschy today, though unless you knew its name you might not connect the typeface with Europe’s Orientalist dream. In the seventeenth century, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher published a series of heavily illustrated books on vast subjects—the heavens, magnetism, China— that included the earliest speculation that a form of the Egyptian’s ancient writing might be connected to living languages. Kircher couldn’t read hieroglyphics (the term means “priestly writing”) but Father Kircher saw in these symbols a puzzle worth our time. That breakthrough had to wait until 1822, when JeanFrançois Champollion announced his decoding of the Rosetta Stone’s hieroglyphic component. You can see the 66 EYE CHART Figure 5.1 Testing with Egyptian Paragon. famous chunk of granodiorite any day you’re in London where Rosetta is waiting for you at the British Museum, with its inscriptions in Greek, demotic Egyptian, and hieroglyphic. All three languages reproduce the same text, and that simultaneity became the key to understanding hieroglyphic as a language. The Rosetta Stone isn’t an eye chart, except maybe in the broadest cultural sense. Early attempts to free the Snellen chart of its serif clutter failed: nineteenth-century audiences expected serifs in display type, and when the serifs were removed they had to be put back in—at least until the fashion passed altogether. Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 67 E There are other charts, other ways of measuring vision, too. Snellen’s 1862 chart is the parent of innumerable variations. For example, there’s the Tumbling E Chart, which consists only of the capital letter E in each of its ninety-degree rotations. The physician only needs to ask: which way does the E point? Left? Down? Up? Right? It’s not what you would really call “tumbling,” a verb you might associate with clowns or drunks. No, the “tumbling” chart is just the opposite: the E moves with military precision. Forward, backward, down, backward, upward. If an E had boots you could hear its heels clicking. The graphic arrangement known as the Landolt C is, like the Tumbling E, particularly useful for the patient who cannot name, or distinguish, the letters of the Roman alphabet we English speakers take for granted. The Landolt C is a fat ring with a cut into it, as if it were the letter C but much weightier. This chart presents the patient with a series of broken rings, with the opening pointing in one of eight directions. There may be only one letter on view, but the bones of the Snellen chart are here. Landolt C strips away Snellen’s alphabet and leaves us with a diagnostic architecture—a tower, a warhead, a phalanx. Landolt C was the creation of the Swiss-French ophthalmologist Edmond Landolt (1846–1926), whose admiration of Snellen I quoted earlier. As director of the ophthalmological laboratory at the Sorbonne, Landolt worked on some of the most important questions of the period. In his lectures on the mechanics of the eye, Landolt demonstrated a 68 EYE CHART Figure 5.2 The Landolt C eye chart. thorough knowledge of visual testing, including the work of Snellen, with whom he had even collaborated on an important scientific paper. Landolt saw many patients, among them some of the greatest painters of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including Degas and Monet, as well as Cassatt, whose vision was seriously impaired by cataracts. No matter how often you go to a museum and walk through an Impressionist show you’ll be struck by the same thing: it’s not just the color and the brushwork, it’s the seeing the color in the world and imagining how to deliver some version of that Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 69 world to the canvas. Did anyone ever see color better than the Impressionists? Impressionism both depended upon and demonstrated the operation of extraordinary vision. Dr. Landolt was testing the visual acuity of some of the most perceptive eyes we know. What would it have been like to see with an Impressionist’s eyes, to be a Cassatt or a Monet or a Degas, at least for a moment? Surely we can see no more than what the paintings themselves tell us about those artists’ eyes. Yet recent explorations of visual analysis suggest that it might be possible to know more about the visual acuity of an artist of the past, and in particular a more precise knowledge of visual loss. Decades ago, viewers speculated that El Greco’s elongated figures were an inevitable result of visual impairment, but that crudely presented idea has given way to more nuanced thinking about art and vision. A recent article in a leading medical journal explores what we might deduce about one Impressionist’s visual decline from a careful examination of a surviving work.9 The case study is Edgar Degas, whose history of eye troubles is well known to art historians. New techniques in visual analysis suggest that we can deploy “ophthalmological knowledge” to deduce quite specific information about the quality of the artist’s vision at a particular point in his life. The analysis is the work of Dr. Michael Marmor, whose focus is Degas’s large Scene from the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey, now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Degas painted The Fallen Jockey in 1866 and reworked the canvas twice, first in 1880–81 and then again sometime 70 EYE CHART Figure 5.3 Degas, The Fallen Jockey (detail). around 1897. It’s an arresting composition, in part for the varying degrees of specificity with which the artist has rendered his subject. Marmor’s project at first seems like a slightly crazy idea. How can we really know what Degas saw other than by looking at the resulting image painted on canvas? That’s exactly the challenge his analysis takes up. By first positing the distance at which Degas might have stood from his canvas while painting, and studying the alterations the artist made Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 71 in the work over time, Marmor proposes that the changes we know in Degas’s technique aren’t simply a matter of late style but the decline in his vision. Through computer technology, Marmor argues, images of the artwork can be defocused with Gaussian blur to match the lines on a standard visual acuity chart (using care to adjust for image size and viewing distance). Several lines of evidence indicate that Degas’ visual acuity was quite good before 1870 but fell to about 20/60 by 1880, 20/100 by 1890, and 20/200 by 1900.10 We can, in other words, imagine Edgar Degas’s eye-test score, almost as if he was in the examining room, and chart the decline of his vision from somewhere in the average range down to 20/200 as cataracts interposed themselves between his brain and his subject. Other eye charts aim to serve different purposes. In the 1970s, the National Vision Research Institute of Australia produced the logMAR chart.11 LogMAR, which stands for the logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution, gets its name from its principle of using logarithmic progression in letter sizes. It’s sometimes called the Bailey-Lovie chart, after its developers. It also is called Snellen, which it isn’t quite, but while it charts its own path, the logMAR chart is clearly a Snellen descendant.12 If the Snellen chart resembles a pyramid, the logMAR chart looks like a badge. 72 EYE CHART The logMAR chart’s graphic advance is elegant because it is simple. Instead of Snellen’s E-topped pyramid, each line of the logMAR chart is a full row of letters. The advantage is that the patient can be tested in the discrimination of shapes across a cohesive set of letter forms. The logMAR chart may be Snellen’s most widely used descendant. It’s designed in a face called Sloan, developed in 1959 by Dr. Louise Sloan, a physician at Johns Hopkins University, where she directed the Low Vision Institute. Sloan letters are often mentioned in the literature on vision testing. Figure 5.4 The logMAR eye chart. Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 73 There are lots of other charts, too, and each makes an argument for a different approach to precision, offering a different equalization of variables. Some have specialized objects, like the EDTRS chart (not a chart for editors, though editors should, like the rest of us, have their eyes checked). EDTRS stands for Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study. Like the logMAR format, the EDTRS format is recognized for the reproducibility of its results, especially important in winkling out the earliest evidence of retinal damage resulting from diabetes. There are eye charts of all sorts, diagnostically sophisticated, graphically ambitious, crafted for particular audiences. One of the most spectacular was designed in the early twentieth century by George Mayerle, whose San Francisco shop advertised the services of an “expert German optician.”13 At the center of Mayerle’s chart are symbols for the unlettered, culminating in an American flag, an eye, and a simple black dot. To the right are Chinese, Russian and Hebrew, to the left English, German (Fraktur type), and Japanese. It’s a snapshot of a practicing optician’s clientele in a vigorously polyglot San Francisco. Note especially the Fraktur, which reflects Mayerle’s own identification as a German physician. It also shows that a hundred years ago, a German reader would be expected to depend on the Latin alphabet as configured in the neo-Gothic format. Mayerle’s chart was published in 1907, just after the San Francisco earthquake. 74 EYE CHART Figure 5.5 The Mayerle eye chart (1907). In the twenty-first century, Snellen may be diagnostically quaint. Some medical professionals want to ditch Snellen altogether, but it remains the ancestor of all distance-reading tests. Tweak it or supersede it, the Snellen chart has had many lives. And still does. Eleven Lines, Nine Letters 75 76 6 Reading Up Close We often read things at great distances: highway signs when driving, of course, or the bus destination we try to decipher as soon as its shape appears on the horizon. Is that taxi light on, the one three blocks away? Most of what we read, though, is inches from our eyes. When you sit in your doctor’s office and are handed a small card, you’ll be told to hold it at “a comfortable distance” as if it were a book or newspaper, and read what you can. This card is a descendant of the other, less celebrated eye chart, the one conceived by Snellen’s contemporary Eduard Jäger von Jaxtthal or, as he’s more frequently called, simply Eduard Jaeger. Jaeger was born in 1818 and died in 1884. His father, also a medical man, had been personal physician to Metternich. A specialist in problems of the eye, Jaeger Jr. wanted to understand how well people actually read—a book, the newspaper, a letter—and created a tool intended to bring exactly that information to the surface. Jaeger called his diagnostic Schrift-scalen or, in English, test-types. Unlike Snellen’s chart, which arranged graduated letters in a vertical pattern in order to test distance, Jaeger arranged graduated text—excerpts of prose—to be held in the hand at a comfortable (that word again) distance. Jaeger’s test-types were first printed in booklet form in Vienna in 1854, eight years before Snellen’s optotypi. Revised and reissued many times, the test-types appeared in a tenth edition in German, French, and English in 1909.1 Jaeger’s booklet consisted of a series of prose passages, usually twenty, laid out in graduated size from barely perceptible type, to type that could be read a room away. Nineteenth-century copies of the Schrift-scalen are, like all ephemera, fragile and rare artifacts. The New York Academy of Medicine Library has a copy of the second edition, published in Vienna in 1857. The booklet consists of reading passages, not only in Jaeger’s native German, but also in English, French, Italian, Dutch, Hungarian, Slovak (“Böhmisch”), Russian, Greek, and Hebrew. Ten languages, ten reading communities, and in that selection one can map out a sense of Middle Europe in the polyglot middle of the European nineteenth century. Jaeger’s Schrift-scalen booklet is a reading world between two diagnostic covers. What did Jaeger choose to have patients read? Surprisingly complex and even lofty texts, it turns out. The numbered passages are not only graduated in size, they’re readings most likely accessible by people who have graduated from university. Jaeger’s sources aren’t the point of the exam (he doesn’t identify the works from which the passages are taken), and teasing out the origins of Jaeger’s test-types would have 78 eye chart made for a frustrating game in the world before the internet. Jaeger gave a few clues—authors’ surnames—which give us a place to start. For German, French, and Italian passages— maybe the three languages for which he anticipated the most immediate use—each of twenty test-type samples comes with an author’s name. Here are famous writers: Schiller, Goethe, Jean Paul, Wieland, Goethe again, Schiller again. Set in larger and larger type, the test-types end with enormous letters. The nineteenth of Jaeger’s sequence of German test-types lands with finality on a passage from—who else?—Goethe. It reads “Auch die Sorge ist eine Klugheit, wiewohl nur eine passive.” (Even trouble is a kind of wisdom, though a passive one). Jaeger must have thought a little philosophy would make the eye exam a worthwhile investment of one’s time. The passage is from the famous record of Goethe’s table talk gathered as Conversations with Eckermann, one Figure 6.1 A moment of Goethe in Jaeger’s test-types. Reading Up Close 79 of the most celebrated of all interviews with a great writer. The honors for the final selection—Jaeger’s No. 20—fall to Schiller: “Der Geist besitzt nichts als was er thut.” The mind (or spirit) possesses nothing except what it does (or makes or accomplishes). Which was or wasn’t a comforting thought to the patient. The Italian excerpts get the same treatment, the author of each numbered paragraph, each from a different text, being identified at the end of that excerpt. Unlike the German writers, the representative Italian authors chosen have not aged well—journalists, patriots, dramatists—men of letters caught in a literary tide that has since run out. The English test-type passages are different: the twenty graduated selections flow from one to the next, shaping a single long excerpt for which there is only one signature— Dickens—at the foot of the last, and largest, reading sample. Figure 6.2 Testing vision with Schiller. 80 eye chart Set in type of different sizes, it’s a portion of Sketches by Boz, which the young Dickens originally published in the late 1830s. Stopping in mid-sentence, the test-type excerpt ends with a cliffhanger to outdo even Dickens, himself a frequent author of periodical installments and a master of the suspended narrative gesture. Most of Jaeger’s languages do just this, organizing all the passages in a continuous sequence from one work. The choice of Goethe and Schiller and Dickens—ruminations on philosophical questions or excursions into character dialect—is typical of the reading material in Jaeger’s tests, which pitch the sophistication of the patient at a higher level than we might expect. In 1868, a New York publisher issued an English-only version of the test-type booklet, presenting the reader with passages “corresponding to the Schrift-Scalen of Eduard Jaeger.” In a preface, the publisher praises Jaeger, but lays out the essential problem with Jaeger’s test-types: “Professor Jaeger made a substantial contribution to our means of diagnosis when he presented his series of test-letters. They have, it is true, no more scientific system than a regular gradation in size, yet in some respects they are quite as useful as the more accurate tests which were suggested by them.” The examining technique would involve bringing a small-type passage—Jaeger’s test-type Number 1 or 2— close to the viewer, then holding it at the point where it is no longer easily readable, and noting the difference in the two distances. Unlike Snellen, however, Jaeger resisted establishing an ideal distance from which the texts should be Reading Up Close 81 read, and that resistance, coupled with Snellen’s more rigid protocol emphasizing a standard testing distance, gave the Dutch eye chart a competitive advantage over Jaeger’s quite different testing model.2 Yet fifty years after its appearance, the Jaeger reading tests were still valued, even if the question of precise measurement was far from settled.3 If Snellen’s chart came to be the most recognizable system for visual testing, it wasn’t that Jaeger’s was superseded in the process. Jaeger booklets gave way to test cards on the Jaeger model, taking the original test-type idea, both streamlining it and adding details. One Jaeger-style reading card even added a few bars of piano music. From a design perspective, the Jaeger booklets are windows into the world of cold type, the period from Gutenberg to the linotype machine when pieces of metal were cast to minute specifications. Used copies can also tell us what their users valued. One nineteenth-century student of typography went carefully through a copy of the Jaeger and annotated each reading selection in the English-language pages. For every passage the reader added a type size name—names unfamiliar to modern ears. Some sound like alternate categories of traditional wedding gifts: Pearl, Agate, Non-Pareil, Bourgeois—then comes sizes once better known than they are today: Small Pica, English, 6-line Pica, 7-line-Pica. Each is the familiar name a printer might have used to describe the text on the page. Marked with a readerly curiosity, this Jaeger booklet records a lexicon of styles.4 82 eye chart Figure 6.3 Jaeger, and Jaeger with music. Jaeger’s test-types have been a standard part of the examination for more than a century. For those of us in the humanities, and particularly those of us working in literature, there’s a temptation to make a special kind of distinction between Jaeger’s handheld card of sample texts and Snellen’s letter chart, suspended twenty feet away. Snellen and Jaeger, far and near: it’s a partnership in visual evaluation techniques that recalls a well-known pedagogical practice. That focus—intensive attention to the words, Reading Up Close 83 patterns, forms, and tone of a piece of writing—is what we’ve been taught to do in English classes. It’s called—with no implication of myopia—close reading. Close reading has a literary history that goes back to the critical work of I. A. Richards and T. S. Eliot in the early decades of the twentieth century. It became the default analytic protocol of literary criticism in the postwar era. We’ve all been brought up on close reading in one form or another, learning to observe, and consider closely, a passage, a line, a word, focusing on rhythm and rhyme, metaphors and repetition, before rushing ahead to symbols and meanings. The parallels between literary reading practice and medical diagnosis are there for the taking. Read slowly, look for evidence, take notes, work from a standard whenever possible, pay specific attention to what seem like small variations and minor details, look for the ways in which what is unremarkable might, with a closer look, tell us something, and above all, listen to what the patient—or the text—has to say. But don’t rely on only what the patient or the text has to say. That’s close reading, and it’s how we’re taught to read poetry, the most complex, resistant, and suggestive form of word-making we have. Social formation, politics, psychoanalysis, gender theory—all have given close reading a run for its money, but not in order to make us stop reading closely. On the contrary, these ways of thinking, often described blandly as “approaches to literature,” depend on close reading in order 84 eye chart to go further. Close reading never was the only way to think about literature. We’re not exactly beyond close reading today, but computers have altered everything about our lives, including how we study literary texts. With the rise of computational criticism and data mining—more generally “digital humanities,” more succinctly “DH”—we’ve been encouraged to think about massive amounts of textual data under the rubric of “distant reading.” A distant reading project might, for example, look at the way a thousand novels that concern marriage—regardless of whether they’re masterpieces or read-and-toss mediocrities—talk about money. It’s big-picture thinking that wants the view from thirty thousand feet. How many marriage plots in nineteenth-century American fiction, including in books nobody has read since, end in financial ruin? Could that tell us something about how people imagined the complexities of domestic structures? If we think of these approaches to literature as ways to engage reading through a text’s context, the practices of distant and close reading suddenly echo what happens in an eye exam. Snellen and Jaeger would be surprised to hear these literary terms, or at least puzzled as to what close and distant mean beyond their own diagnostic procedures, but the parallels are available if we look for them. Emphasizing distance, Snellen’s chart asks for a kind of absolute reading—a single letter, picked out of white space, recognized by curve Reading Up Close 85 and stroke, and meaning nothing. As a consequence, Snellen’s chart feels like reading in the laboratory. Jaeger’s test-types do something different. It’s not just that the test-type diagnoses visual acuity with a smaller distance between eye and object. Instead of Snellen’s absolute protocol, Jaeger tests visual acuity while acknowledging the importance of context. You read a word by recognizing it, or parts of it, and you move along to the next one, drawing upon everything you know about how sentences work and what part of speech is most likely to follow. It is, of course, what we mean by reading in the ordinary sense. E Today we’re likely to look at Jaeger’s work with different eyes. If the test-type booklet hadn’t been invented when it was, it could have been a writing project of the avant-garde Oulipo group, which experimented within idiosyncratic and self-imposed rules. Georges Perec composed an entire novel, translated into English as A Void, without ever using the letter “e.” Another Oulipo figure, the Italian writer Italo Calvino, who died in 1985 at the age of sixty-one, is admired for a stylistic invention that comes closest to what the test-type booklet seems to offer. In his fiction If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller (1979), Calvino offered the reader a complex set of narrative half-gestures. The work’s plot, such as it seems to be, is composed of a series of stories, each of which breaks off without resolution before the next begins. With its sequence 86 eye chart of doors that open without ever closing, Calvino’s fiction inhabits the postmodern world of the dream narrative. Yet it also recalls the test-type’s dreamlike passage through one language and into the next, from Dutch to Hungarian to Slovak. One 1875 test-type booklet has its own dreamy movement from one language to another, as it shows off passages imagined to be good diagnostic tools in the decade after the American Civil War. It’s a strange menu of writers. The Latin text is from Tacitus, the German from the popular romantic writer Heinrich Heine. Other names we are much less likely to know. For the French text, the needed paragraphs are plucked from Rodolphe Toepffer, an early nineteenth-century Swiss writer and caricaturist. In 1837 Toepffer published Histoire de M. Vieux Bois—the story of Mr. Old Wood—a small volume compiled of illustrated panels accompanied by text. It’s sometimes referred to as the first comic book.5 The Italian excerpt is by Silvio Pellico, a pre-Risorgimento writer and patriot. During his lifetime Pellico was known for his Le mie prigioni (My Prisons), a memoir of his decade of incarceration as punishment for supporting the Italian nationalists. The Dutch example is drawn from the writings of Simon Styl, a late eighteenth-century writer and author of De opkomst en bloei der Vereenigde Nederlanden (The Rise and Flowering of the United Netherlands), published in 1774.6 Reading Up Close 87 The booklet’s entry for an English text by John Lothrop Motley, a nineteenth-century American diplomat who traveled, raised a family and, apparently without a command of the Dutch tongue, wrote popular histories of the Dutch republic. The passage here is from one of Motley’s books on his favorite subject: the indomitable spirit of the Dutch. It begins: The Gallic tribes fell off and sued for peace. Even the Batavians became weary of the hopeless contest, while fortune, after much capricious hovering, settled at last upon the Roman side. Had Civilis been successful, he would have been deified, but his misfortunes, at last, made him odious in spite of his heroism. But the Batavian was not a man to be crushed, nor had he lived so long in the Roman service to be outmatched in politics by the barbarous Germans. He was not to be sacrificed as a peaceoffering to revengeful Rome. Watching from behind the Rhine the progress of defection and the decay of national Would a twenty-first-century eye exam asking the patient to read the sequence “while fortune, after much capricious hovering, . . . .”? As with other test-type samples, the Motley excerpt is enough to make us wonder at the reading level and sophistication of individuals undergoing nineteenth-century visual accuracy tests. The Jaeger test-types brought real reading into the diagnostic process, and acknowledging, in its multiple languages, that reading words is always more complex than 88 eye chart reading symbols, even when those symbols are alphabetic. When we sit for an eye exam, we can hold the Jaeger-style card at a comfortable distance, as the doctor asks us to, and we can read off the passages provided, whether they’re about Roman battles, goodness in a fragile world, or some other less sensational subject. But there’s no escaping the beautiful strangeness of the Jaeger test-types, where language is made to do very unlanguage-y things. The test-type document is a piece of performance art in a lab coat. Reading Up Close 89 90 7 Looking for Trouble Go to the website for the retail company The Sharper Image and you’ll find products that purify your air, offer you a massage, make your car more technologically fashionable, assist you in mastering your backyard, entertain your kids, and ennoble your man cave. There are also eyeglasses. Lots of them: foldaway glasses, polarizing glasses, glasses to help you find your golf ball, glasses made for long hours in front of computer games. If you’re someone who enjoys reality so much that you want to reexperience it immediately, The Sharper Image offers sunglasses with a covert video recorder so you can film what you see as you’re watching it and play it back later. The sharpness of the image is one of the selling points of the company’s eyewear line, but generally speaking the firm’s profile suggests that you’ll also look sharp if you buy these goods. Sharpness of vision is what the eye chart measures. With its economical format and ingenious system of measurement, Snellen’s project offered a simple way to categorize degrees of visual sharpness. Armed with that information, eye care professionals could advise on how to compensate for weakness and astigmatism. Lenses could be crafted to help the viewer see more clearly—not to make the image larger, but to make it sharper. It seems, however, that sharpness of vision was not always without its drawbacks. In fact, it could be a symptom. One of the most famous and influential figures in the history of criminology was the Italian physician Cesare Lombroso. Born in 1835, Lombroso proposed a theory of criminal atavism. Criminals, Lombroso argued, were reversions to primitive human states. In 1876, Lombroso published L’uomo delinquente (Criminal Man), the work that would define his career. Lombroso understood the criminal mind within a powerful, and gloomily fatalistic, view of human character. There had been earlier attempts to identify the physical characteristics of the criminal, the depraved, and the insane. Nineteenth-century fiction is full of such caricatures. Lombroso offered system. Lombroso, determined to prove that the tendency to criminal behavior could be seen in the shape of a person’s face and head, would develop the idea further, making use of advances in the new medium of photography to secure what he believed was a visual vocabulary of criminal types. (“Black” and “Mongol” were negative categories Lombroso deployed as a means of defining progress.) Cataloging headshots of convicted persons, Lombroso proposed a kind of somatic lexicon of corruption. Those who were “born bad” 92 eye chart would have physical characteristics—a sloping forehead, asymmetrical features, distended ears, snub noses—that were clues to inherent criminal tendencies. Features of the criminal type had to be measured, identified, and used as predictive tools. Lombroso’s methods of “detection,” while not uncontroversial even in his own time, had a powerful effect on the study of criminal behavior. If criminals were different from the rest of us, did their sensory organs operate differently? Under the terms of analysis Lombroso was developing, even unusually good eyesight could be associated with bad behavior. Did the criminal see as well as the honest citizen? To this end, Snellen’s eye chart was enlisted for the purpose of identifying criminal types. A late nineteenth-century Dictionary of Psychological Medicine notes how murderers and thieves scored on a Snellen test: Ottolenghi examined 100 criminals with Snellen’s types in the open air, using various precautions to ensure uniformity and accuracy. The results were – Visus (average) for 82 thieves = 1.8 “ “ 18 homicides = 2.2 “ “ 100 criminals = 2.0 In one of the homicides sight was very keen (V = 3).1 The protocol— “various precautions” and all—was designed to uncover measurable data concerning criminal vision. In a small sample of one hundred individuals, murderers Looking for Trouble 93 are confidently presented as one single class of person and thieves as another class (what about someone who had stolen and later killed? were all persons convicted of homicide really comparable?). Presumably the figures reported above are slightly higher than what the innocent man or woman might be “expected” to achieve. But it’s the fundamental categorizability of the criminal that seems most remarkable. The conclusion: murderers had measurably sharper vision than thieves. The report even picks out one exception of a gimlet-eyed killer whose vision is unusually sharp—a sort of data-driven exclamation point. Perhaps the criminal with better-than-average vision could be capable of the worst crime possible. Lombroso’s ideas gave credence to a scientistic obsession with pinpointing the features common to those who were found guilty of violating the law. The theory produced all sorts of gradients and tests. Murderers might score well on the Snellen test, but not all senses within the criminal body were “heightened.” Tests evaluated such sensory capacities as the criminal’s “gustatory obtuseness”—presumably, the lack of a refined palate. (One can only wonder at the discriminations of taste convicts were asked to make.) The examinations also reported on the extent of criminals’ sexual precocity, darkly described as being “both in natural and unnatural forms.”2 Lombroso’s analytic procedures should strike us (as they did some of his contemporaries) as ripe with class and race prejudice, but his efforts uncomfortably foreshadow modern 94 eye chart fears of invasive surveillance. Between Michel Foucault’s all-seeing panopticon and the iPhone that tracks your every move there was the Lombroso school of criminology, encouraging a belief that complete knowledge of the criminal mind and the criminal body—maybe of every mind and of every body—was a necessary precondition of public safety. Lombroso’s ideas now seem part of our bad eugenicist past if not our surveillance-mad present. In its attention to detail, however, especially the details made newly available by the camera’s reliable output, the Italian criminologist’s work might be looked at in a slightly different way. Although the conclusions may be unconvincing, Lombroso’s project was about attention to detail. Photography made that attention newly possible. This system of visual categorization has a distant resonance with the connoisseurship of the American art historian Bernard Berenson, Lombroso’s younger contemporary. Born Bernard Valvrojenski in Lithuania in 1865, Berenson was one of the most influential authorities on Italian Renaissance art. He exhibited what the Gilded Age millionaires admired and rewarded: a confident ability to determine the authorship of Old Masters. Berenson drew upon the investigative technique pioneered by art historian Giovanni Morelli (not coincidentally, Morelli was also a medical man and a teacher of anatomy). Berenson’s skill and his success in promoting it made him among the most important art advisors of the early twentieth century, one of the Great Ages of Collecting. Following Morelli, Berenson’s Looking for Trouble 95 technique was in part grounded in his observation of details that others overlooked, as in the case of his famous attention to fingers and hands in works that might or might not be by Botticelli. Where lesser critics pored over the face of a Madonna, Berenson looked where he believed the painter, whoever it might be, thought the viewer wouldn’t be looking. Berenson and Lombroso, criminologist and connoisseur, shared an aptitude for symptomology, attending to details that might be overlooked by other less keen observers. In their different ways, they were close readers. E The year 1900 fell within a decade rich for the interpretative arts, the sciences, and the pseudosciences, too. In that year, Lombroso’s major work was translated into English, and Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams. Freudian psychoanalysis was charting a guide to the mind’s crawlspaces, and like Lombroso and Berenson, the Viennese doctor’s methods depend upon attention to unobserved details. Their projects remind us how readable the body became—or appeared to have become. Berenson read fingers, Lombroso foreheads and ear shape and visual acuity, and Freud read language, the space where dreams and anxieties are written out in speech. What the patient said about a dream became a way to determine what the patient could not otherwise say. Dream interpretation was a semi-magical procedure with a pedigree going back to the Bible and beyond, but Freud proposed 96 eye chart that what could not be seen—or known—by the conscious patient could be released—seen—through careful analysis of dreams as restructured through spoken language. What thrilled Vienna and the world about Freud’s project was the revelation of the concealed, the thing that was always present but invisible: a trauma, a fear, a desire, a memory. Freud’s archive of encounters with his patients, recounted in The Interpretation of Dreams and the cases of Dora, Anna O the Wolf Man, and other patients, are documents of vision—not the kind that the eye chart tests, but vision nonetheless. In Freud’s century, complex secrets were there for discovery. One of the most famous is the Rorschach test, those folded sheets in which mirrored blotches of ink did or did not appear to the viewer to be a butterfly or a penis. The Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach had been working to develop a test for diagnosing schizophrenia. Psychodiagnostik, the work on which his reputation would be based, was published in 1921. Rorschach died the following year at age thirty-seven. His testing protocol, based on a series of inkblot images, was developed and extended further by his followers. Hermann Rorschach didn’t singlehandedly invent the idea of puzzling over blobs (though as a Freudian he knew that sometimes a blob isn’t just a blob), but he brought the procedure to a new level of visibility and celebrity. Rorschach had made of ink splotches a kind of Freudian eye chart. The process of producing artistic images out of inkblots is called klecksography, from the German word klecks, or inkblot, which had been the basis of a children’s game. (The Looking for Trouble 97 young Rorschach knew the game, evidently well enough that he earned the nickname “Klex.”3) The Rorschach test became part of twentieth-century psychological testing, though not uncontroversially, and one of popular culture’s windows into diagnostic treatment. Who knew what the blots meant or could reveal? One of the best-known examples is Daniel Keyes’s 1959 short story “Flowers for Algernon,” about Charlie, a mentally disabled man whose intelligence scores improve dramatically when he becomes an experimental subject. Charlie is given a sequence of examinations, one of the first being what he calls a “raw shok” test. It wasn’t until the candy-colored 1960s that a public fascination with the Rorschach test made the inkblots a topic of broad interest. Social attitudes have moved on, but the Rorschach test has never really gone away. In 2009 the Watchmen graphic novel series was made into a film, bringing to the screen the story’s vigilante antihero, Rorschach. If your name is already Rorschach, everything is a test. Today you can buy Rorschach: The Inkblot Party Game, which comes in a box whose front panel redundantly exclaims “Perfect for Parties!” There is no Snellen Party Game, though it’s surely only a lack of attention on the part of the games manufacturers that’s spared us some ages-18-and-up version of an eye test. It would be perfect for parties. E Modern diagnosis is all about looking for the point of weakness, and if trouble follows, the means of addressing it. 98 eye chart Compared to psychoanalysis, inkblots, and photographicbased pseudoscience, Snellen’s eye chart feels pretty benign. The serious work of assessing eye problems remains in the hands of the ophthalmologist, peering into the organ itself. Retinas are detached, cataracts thicken the lens and shut out light. The eye chart is an inadequate tool for assessing, much less correcting, these conditions. Still, we tend to think of eye trouble as reducible to what eyeglasses can correct. If poor vision needed a mascot there could be no more familiar spokesperson than the genial and irascible Mr. Magoo. Created in 1949 by the animation group UPA, Mr. Magoo is a gentleman of a certain age, short, bald, and nearsighted. Neatly dressed and infinitely curious, Mr. Magoo explores the world around him, his cheerful disposition broken only by moments of frustration that pass as quickly as summer rain. Unlike the animated zoo of mice and bunnies and coyotes, Mr. Magoo was always human, and his adventures owe more to the world of silent comedy gods like Buster Keaton than to the Disney empire of ingenious fauna. Magoo was popular enough to be cast as Scrooge in an animated version of Dickens’s Christmas classic; the 1962 featurette Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol still reemerges, in all its period glory, at holiday time. The world of Mr. Magoo is shaped by his inability to see what’s staring him in the face. Marcelo’s leg of mutton problem as recounted by Daza in the seventeenth century is Mr. Magoo’s everyday modern experience, with the difference that there’s nobody to tell Quincy Magoo he’s made a terrible Looking for Trouble 99 mistake, and even if there were, Mr. Magoo would brush it off. The actor Jim Backus made Mr. Magoo come alive, giving him one of the most distinctive voices in animated film and making Magoo one of the most recognizable animated characters of the 1960s. Mr. Magoo’s delight in the world he can hardly see protects him from his own limitations, but the narratives that could be built around the struggle of Magoo vs. World delighted in the possibility that humans, in all our limitations, still endure. In 1957, Mr. Magoo won the first of his two Oscars (the award went to Stephen Busustow, who produced not only the winning cartoon but all three of the nominees in that category). In the cartoon “Mr. Magoo’s Puddle Jumper,” our nearsighted hero buys a car—an antique electric car, at that—and takes his nephew Waldo for a ride. Figure 7.1 Mr. Magoo negotiates an unlikely eye chart. 100 eye chart Magoo drives straight into the ocean. As he motors along, Magoo’s running commentary on the underwater traffic and the state of Beverly Hills is an in-joke for the Hollywood community. It’s a nice detail that Mr. Magoo was a college graduate—a Rutgers man—with the sort of raccoon-coat spirit that once stood for uncomplicated alumni fervor. But even Mr. Magoo had to face the diagnostic music, as he does here in this eye test. The exam he faces has been dreamed up by the animators, and despite the format, it’s an improbable, and quite unSnellenian, selection of letters. Unlike us in the non-animated world, Magoo’s reading of the eye chart has no consequences at all. Beside, Mr. Magoo’s eye trouble makes our own a little easier to endure. He’s an optometric Everyman, crankysweet, playing out our own unresolvable encounter with the visible world. Looking for Trouble 101 102 8 Eye Terror We know what’s involved: the drops, the waiting, the blurred vision, the concern that one’s eyes have weakened (by how much? is this normal at my age?). One might be anxious during an eye test, but things could be much, much worse. E. T. A. Hoffmann, the Prussian-born writer who gave children The Nutcracker and adults nightmares, published “The Sandman” in 1816. It is, among many other things, a masterpiece of the horror-fantasy genre, as disturbing as Kafka’s stories would be a century later, and it is all about vision and eyeglasses. In “The Sandman,” Nathanael is a young man obsessed with a strange figure who comes to the family home, has heated conversation with his father, and in the ensuing events precipitates the father’s death. The visitor, or his doppelgänger, reappears in the young man’s life, now as a seller of artificial eyes and pocket spyglasses. When a mysterious figure and his daughter move in next door, the young man becomes attracted to the strangely immobile young woman he can see at the window. Nathanael meets her at a dance and is enraptured, forgetting his beloved Clara. We discover that the daughter is an automaton, and her eyes artificial, but Nathanael alone cannot see that the “daughter” is not alive. Struggling to maintain his fragile sanity, Nathanael prepares to depart the town with Clara. They climb the town hall’s tower for one last view. But as in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, bad things happen in towers. Seeing once again the strange figure that has obsessed him, Nathanael first tries to kill Clara and, failing, throws himself over the edge. Hoffmann’s story concentrates on the protagonist’s dread and the uncanny appearance, or presumed appearance, of a single, menacing figure at different points in Nathanael’s short life. The artificial girl, and the mechanism that controls her, are critical to Hoffmann’s development of his protagonist. What about those sightless artificial eyes? What kind of vision is this story describing? A work of fiction is not an appliance, but this particular tale has gained fame for the diagnostic use to which Freud put it in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny.” For Freud, the uncanny is the thing that is both familiar and unfamiliar, both heimlich—homely, familiar—and unheimlich, meaning the opposite. A doppelgänger is both familiar and unfamiliar, and so a source of terror. That terror, however, is of a particularly powerful and persistent kind because it brings the frightened person not to any alien environment but to the most alien of all environments: home. 104 eye chart Dreamlike in its jarring episodic structure, “The Sandman” has been adapted many times, with each adaptation watering down the disjunctive form in which Hoffmann tells his tale. Hoffmann’s original narrative, on the other hand, is riddled with ulcers or holes, the sort of deficits that would, were a text a physical body, be compensated with prostheses. The augmented body, the artificial body, the appliance: these theatrically rich materials ground the ballet classic Coppélia (1870) with its score by Léo Delibes, or Jacques Offenbach’s much admired opéra fantastique, Les contes d’Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann), given its premiere in 1881. In Offenbach’s opera the protagonist, also called Hoffmann, recounts three tales of thwarted (or, more exactly, perverted) love, the first focusing on the beautiful Olympia, a figure revealed to be a doll just moments before she is destroyed in what is essentially a custody battle between her male creators. The English filmmaking team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger made the French opera into a hauntingly strange English-language film.1 The opera and film, and in some productions the Coppélia ballet, play out the theme of artificial eyes. When in the film version Olympia is destroyed, our last sight of her is a mechanical head lying amid the wreckage of the doll’s body parts. The character of Olympia is an automaton, but the head belongs to the dancer Moira Shearer, who has performed the role. The music stops. We hear only the ticking of gears. Both lifeless and never alive, Olympia’s head dares us to police the Eye Terror 105 boundary between body and machine while her eyes stare sightlessly out at viewers. E Hoffmann’s story and its adaptations in succeeding generations are part of the nineteenth century’s fascination with the horror of vision—the sightlessness of the automaton’s eyes, the possibility of sight beyond sight, the danger not only of blindness but of its opposite, the inability not to see. And in these anxieties, technology and fantasy converge. In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen, a German mechanical engineer and physicist, accidentally discovered an unfamiliar frequency that he named X. The first image Röntgen produced was an x-ray of his wife Anna’s hand (“I have seen my death,” she is reported to have said). X-rays were quickly deployed— in medical exams, in carnivals, and for quotidian tasks such as measuring people’s feet for correct shoe sizes. Five years after Röntgen’s discovery, Freud published his study of his patients’ dreams. Suddenly, there were two powerful diagnostic systems for exploring the interior, and neither without complications. In 1897, midway between the breakthroughs of Röntgen and Freud, H. G. Wells published The Invisible Man, a work that quickly became a classic of science fiction. In Wells’s novella, a mysterious character called Griffin arrives at an English village, completely muffled in clothing from head to toe. We learn that Griffin is a scientist who has experimented with a formula for invisibility, and only by being wrapped can 106 eye chart we see him or—in language we would learn some decades later from particle physics—the evidence of his presence. The story develops as a drama that ends with Griffin’s death. He is stripped, his naked body materializing at last. In the 1933 film version of The Invisible Man, the actor Claude Rains, who plays the title character, is invisible throughout the drama, materializing only in the last shot. The attending physician warns, “His body will become visible as life goes.” And in fact, as life goes, the viewer is transformed into a diagnostician in reverse, glimpsing first the skull, then the external features of the now peacefully dead title character. Rains’s voice is with us throughout the film, but his face appears only in the film’s final moment. Figure 8.1 The invisible man’s deathbed visibility. Eye Terror 107 Wells, however, describes Griffin’s death with greater visual violence: When at last the crowd made way for Kemp to stand erect, there lay, naked and pitiful on the ground, the bruised and broken body of a young man about thirty. His hair and beard were white—not grey with age, but white with the whiteness of albinism, and his eyes were like garnets. His hands were clenched, his eyes wide open, and his expression was one of anger and dismay.2 Since the moment of Röentgen’s discovery of mysterious emanations and the development of an important diagnostic tool, the mechanism quickly took its place as a visual joke. Countless animated films and cartoons depicted the patient (or a cat, a goldfish, anything with an unseeable internal structure) behind an x-ray machine. The subject’s body, extending beyond the device, would be recognizable, but the mechanism would cover a crucial area—the chest, the stomach, the head—revealing some secret within. X-rays reveal Homer Simpson’s secret: he has a crayon stuck so far up his nose that it has lodged in his brain. Surgeons remove it. Then they put it back in. The x-ray is a form of non-human vision, capable of mimicking the organ of sight but revealing much, much more, maybe too much. It’s a common feature of imaginative writing about x-rays that the penetrating waves emanate from someone’s eyes. Why dream up an x-ray wristwatch 108 eye chart or belt buckle when the eyes themselves offer such an irresistible locus of inhuman power? Superman, Earth’s most welcome extraterrestrial and the most famous of the modern era’s superheroes, demonstrates again and again the not unproblematic status of his abilities. In February 1942, during the height of the Second World War, Clark Kent attempts to enlist in military service, but he doesn’t pass the physical. Yes, he’s “physically superb,” the doctor assures him, but he’s failed the eye test. How is this possible? A caption box explains: GLANCING AT THE WALL, CLARK DISCOVERS THE ANSWER—IN HIS PREOCCUPIED STATE HE HAD INADVERTENTLY GLANCED THROUGH THE WALL BY MEANS OF HIS X-RAY VISION, AND READ THE LETTERING ON AN EYE CHART IN THE ADJOINING ROOM! Figure 8.2 Superman fails an eye test. Eye Terror 109 It wouldn’t be quite the same revelation in upper- and lowercase letters. Clark might not even notice, though, what we can see: the eye chart he was supposed to read is, strangely enough, composed of letters in alphabetical order—something a good eye chart would never do. (Superman and Mr. Magoo may have the same optometrist.) We may have lived with psychoanalysis too long for us not to read internal conflict into Clark’s misreading, but Superman did soon go on to battle the “Japanazis,” as the comics world dubbed the Axis forces. In Roger Corman’s eminently low-budget 1963 film X, Ray Milland plays a doctor who develops a formula for eye drops that produce x-ray vision. We see him first experimenting on a small laboratory monkey, but the animal dies shortly after demonstrating that the serum basically does what the doctor wants it to. Milland’s character, Dr. James Xavier, makes the researcher’s sacrifice and turns himself into the first human subject, becoming a man with x-ray vision. Corman’s soft thriller gives us Dr. Xavier discovering his powers—looking through women’s clothing at a dance party (the camera is so discreet that it’s hard to imagine a less prurient exploitation of this visual superpower—and Xavier reminds us that he is a doctor, after all). Now he’s diagnosing a child’s medical condition without the trouble of an internal examination, now he’s seeing otherwise imperceptible broken ribs. But while Dr. Xavier’s diagnostic power grows, there’s a downside. His condition is unstable, and his eyes increasingly see the world as a dizzying explosion of moiré patterns (X delivers its visuals before the era of CGI). 110 eye chart At the film’s turning point, Xavier demonstrates his ability by reading a Snellen chart—or rather by reading through it. Facing the familiar graphic test, Xavier gets everything wrong. Or so it seems, until the examining physician lifts the hinged eye chart to reveal a second, different Snellen chart underneath. (Do hinged Snellen charts exist? What would their purpose be?) Like Superman peering into the next room, Xavier has been reading the chart below the one visible to us. There’s an argument, a struggle, and Xavier accidently pitches his colleague through a plate glass window, sending him many stories down to his death. In a moment, Milland’s character becomes what he was destined to be—a noir protagonist on the run. He holds up in a cheap circus run by Don Rickles, working mind-reading tricks (or, in this case, demonstrations of extra sight). There Xavier is compelled to perform a parody of medical consultation. Ordinary people of modest means are brought to see the remarkable diagnostician for whatever they can afford to pay. We see the unwealthy sick lined up, and Rickles happily pocketing two bucks now from this patient, now that one. It’s a combination of the modern museum’s pay-what-you-wish and devotional attendance at a miraculous site—the democratic gesture of socialized medicine tempered by the physical discretion of a psychoanalytic session. The whole thing is a sham. Or is it? Milland’s Xavier sits opposite the patient, looks, and pronounces—to the patient it’s a miracle, but Xavier is only reading the marks within the stranger’s body, and he does it reluctantly and with a desperate sense of endgame. Eye Terror 111 In the inevitable last chase with the police, Xavier is speeding along down a California highway shadowed by a helicopter. With his eyes working overtime, he’s almost blinded by his capacity for extraordinary vision. Somehow he escapes one last time, only to arrive suddenly at an evangelical’s tent rally. Religion, judgment, the end-limit experience of vision: the film’s final moments invoke, as if inevitably, the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew with its admonition to pluck out the eye that offends you. Which is apparently what happens in the abrupt last shot, as we see Xavier in close-up, his eye sockets glowing red. Released with an explanatory subtitle (X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes), Corman’s film larks through two favorite themes of mid-century popular culture—the ability to be invisible, and the ability to see what cannot be seen. They’re two sides of one scopophilic coin. Superman (born 1938) is the best known of the superheroes endowed with hypervisual powers. (A slightly earlier female character, Olga Mesmer, demonstrated her x-ray vision in Spicy Mystery Stories, which ran from 1937 to 1938.) The decades since Superman have produced numerous superheroes endowed with visual capacities whose unnatural range resets the expectation of what superpowers must now be. Today the seeable and the unseeable are partners of our imaginary—and political—engagements with the world. The invisibility of the body may not be a practical reality in everyday life, but technological advancements are constantly expanding our ability to be present in absentia. Nowhere is 112 eye chart invisibility more prized than in military operations, where the “invisible” aircraft and the pilotless drone play out with deadly seriousness the dual visual states of x-ray capability and visual undetectability. E The x-ray developed rapidly as a diagnostic tool and a source of anxious visual humor, but before cartoon cats showed us their rib cages, there was Marcel Proust and A la recherche du temps perdu. In Du côté de chez Swann (1913), the first installment in Proust’s masterwork beyond genre, Marcel recalls a visit to his aunt Léonie, whose physical condition has reduced her to living in two rooms, attended by her servant Françoise. Conversation turns to a visit Françoise might make to her married daughter. The servant conceals the tension between herself and her son-in-law, but to Françoise’s astonishment, Marcel’s mother acknowledges the problem, discreetly and sympathetically. Françoise cannot contain her surprise: “Madame knows everything. Madame is worse than the x-rays” (she said x with an affected difficulty and a smile, mocking herself—an ignorant woman—for using this learned term) “that they brought for Mme Octave and that see what you have in your heart.”3 Françoise goes away, perhaps to hide her tears, and the narrator tells us that his mother is the first person who has made Françoise feel that anyone might be interested in her emotions and her inner life. Maman is, in other words, the Eye Terror 113 x-ray diagnostician of the heart that Françoise imagines to be the purpose of the new technology. The x-ray is only one feature of what the French film critic Christian Metz named the scopic regime, a term now used to identify endless variations on seeing what cannot be or is not meant to be seen. Corrected vision, the x-ray, and the dream of invisibility are all connected, if not by straight lines, within the scopic regime of modernity. Of these, the dream of invisibility may be the oldest desideratum—maybe only the dream of flight is an older one. We have dreamed of invisibility at least since we were able to recount our dreams in language. In the republic, Plato deploys the myth of a magic ring that conveys invisibility on its wearer. In the nineteenth century, Richard Wagner made the tarnhelm, a magical headpiece that conveys invisibility as well as the capacity to shift shapes, a central plot device in his massive operatic project Der Ring der Nibelungen. Sauron’s ring in Tolkien’s saga and J. K. Rowling’s cloak of invisibility are modern-day relations. There are countless magical versions of creatures moving through the world unseen. The world of angels and other beings from another dimension occupy if not our atmosphere then prime real estate in our collective imaginations. In technological modernity, it’s a cooler, non-magical understanding of invisibility that compels us, driving forward a new enthusiasm for seeing what is unseeable. The emerging science of nanorobotics has its precedents in techno fantasies like Fantastic Voyage (1966), 114 eye chart in which a medical team, featuring a tiny Raquel Welch, is reduced to microscopic scale and injected into a patient’s system in order to complete a perilous medical procedure. The animated Magic Schoolbus series features Miss Frizzle, a redoubtable science teacher who miniaturizes her young charges and takes them on adventures in learning. Her school bus may be magic, but the technological dream it inhabits resonates with research possibilities of nanotech, robots small enough to enter the system and intervene with malignant tissue or remove pollutants from a contaminated liquid. Think about drones and Google Earth scanning our world with their heightened “opticality,” and think again about policing the border between the scientific and the fantastical. Like the x-ray and the microscope, the eye chart has moved beyond the doctor’s office to become a means of releasing the imagination in ways unintended by its inventors. Eye Terror 115 116 9 Eye Poetry The Snellen chart is a tool for physicians, and inadvertently for poets, too. One need only listen, for example, to Billy Collins, who served a term as poet laureate of the United States from 2001 to 2003. Collins was then and remains today one of the most popular poets writing in English. His style is unfussy, even ambitiously unpretentious. Early on, Collins emulated Wallace Stevens, the mandarin of poetic mandarins, conjurer of poems that read as Olympian mysteries. Collins writes poetry that’s nothing like that. In a recent interview with the Irish Times, Collins laid down a principle of poem-making, an architectonics of poetry: “The beginning of a poem should always be very clear, to get a reader on board, and only then can you be confident that when you move into less obvious areas of metaphor or fantasy that they will go with you. It is like an eye chart, with its big E at the top, and the letters getting less legible as it moves along. A poem should be like that.”1 The metaphor is trickier than it sounds. A poem should be like what, exactly? Collins’s eye chart is a funnel, a moving target, a shape-shifting object that shunts the reader along from the real of “its big E at the top” to something less legible. It’s in the less legible parts of the eye chart that the poet can get his or her hands dirty with the “less obvious area of metaphor or fantasy.” So what can’t be read in the Snellen chart may not be inaccessible. It just may be the place where metaphor and fantasy are finally liberated from the text. A lot of texts, poetry included, are eye tests. Anything with small print—the insurance rider on your car rental, for example. Things can be eye tests, too. When I was a boy, my grandmother sometimes asked me to thread a needle for her. I could hold the sliver of steel up to the light and guide a colored thread through a lozenge of air. Her needle was an eye test that I could pass—it was simple enough for a boy of six—and she couldn’t. For centuries, that lozenge has figured in our thinking about vision, and other things, too. The eye of the needle isn’t just small: it’s a trope for smallness. The needle’s eye can’t be tested; it’s already a test. In Matthew 19:24 Jesus preaches about the needle test. The Bishop’s Bible—predecessor to the King James Bible and the one Shakespeare would have known—translates the passage this way: And agayne I say vnto you: it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a nedle, then for the riche, to enter into the kyngdome of God. This has always seemed pretty simple to me: if you want to go to heaven, you’d better be poor. If you’re not poor, get poor. Francis of Assisi showed us that it’s really not difficult 118 eye chart to do. Maybe an ophthalmological interpretation would find a different paradox, a different agency here: it would be easier for a rich guy to thread a camel through a needle’s eye than to enter heaven. The needle becomes an eye test, which becomes an obstacle test. The poetry of the Biblical verses is shaped by the rhythms of Hebrew and Greek and Early Modern English. The great seventeenth-century metaphysical poet George Herbert knew about the shape of metaphor and about the shape of poems. “Easter Wings,” perhaps his most famous lyric, represents the forgiving grace of resurrection as a pair of wings bearing the penitent sinner to paradise. The poem’s lines are arranged in lines that look like a pair of bird’s wings in full flight. Lines begin long, shorten, then lengthen again. This happens twice, once for each wing. Bird wings, divine beneficence made almost visible to mankind: grace is the artwork we can never look upon as mortals. “Easter Wings” is the most distinguished entry in the category of writing called pattern poems. The shape of the textual object reflects its subject, and sometimes is its subject. Form follows and informs content; gesture and meaning are indivisible. “The Flower,” another of Herbert’s poems, is about man’s relation to the world, and to God (which for Herbert is indistinguishable from the world). In “The Flower,” Herbert plays on the longstanding metaphor of the world as God’s book—the book of nature—that goes hand in hand with Scripture, the book of revealed textual truth. Both are hard to read. Both test us. But, Herbert earnestly hopes, Eye Poetry 119 Figure 9.1 George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” tests many things, including eyes. if we could only make it through those books we would be ready for God. And to read them we need to be able to read their symbols. Or, as Herbert puts it, we need to be able to make out the letters in front of us: We say amiss This or that is: Thy word is all, if we could spell. Herbert’s world is a spelling bee, a reading comprehension exam, a cosmic eye chart. A century after Herbert’s death in 1633, Alexander Pope observed “’Tis certain, the greatest magnifying glasses in the 120 eye chart world are a man’s own eyes, when he looks upon his own person.”2 In the twentieth century, a renewed interest in typographically self-conscious verse emerged under the label “concrete poetry.” In the late 1950s and 1960s, there was a new enthusiasm for poems that flaunted their architectonics, works that arranged words in shapes and patterns that could be mimetic of their subject or suggestive of the relation between subject and the act of writing about that subject. So a poem like Mary Ellen Solt’s 1966 “Forsythia” is composed of the letters in the plant’s name, splayed out like the branches of forsythia, the repeating letters threaded together by dots and dashes. The whole typographic floral arrangement is nestled into a rectangular base that, on inspection, turns out to be composed of the word forsythia, the letters of which inaugurate nine words: forsythia out race springs yellow telegram hope insists action. Of course, every poem ever composed is just as concrete as any other poem, which is to say that no poem is as concrete in the same way that concrete is concrete. There’s an absurdity about calling a poem a concrete thing, but mainly because that would buy into an idea of concreteness as being physical, a position against which poetry takes a stand simply by being poetry. Instead, the typographic self-consciousness of picture and pattern poems, including these by Herbert and Solt, insists that by rewriting the formal rules of linguistic arrangement a poem can lend authenticity to our experience of the world. So the concreteness of Solt’s poem emerges from its enthusiasm for language as a material. Eye Poetry 121 It’s a picture poem as much as Herbert’s “Easter Wings” is a picture poem, with the added task of transforming forsythia into an acronym that looks as if it might be a slogan (the words “hope insists action” feel awkwardly connected, as if it were a further abbreviation for something). “Forsythia” is a poem with Dadaist roots. One of modernism’s founding principles is that founding and finding can be intimates. From Duchamp’s Fountain to the poetry created from isolating the words of sportscaster Phil Rizzuto or the cries of parents at a kid’s soccer match in Sam Cohen’s recent “Sideline Poetry,”3 found art may be about many things, but one of those things is going to be irony. Is the Snellen chart concrete poetry? (Is the chart even capable of irony?) Is it a found object? Does it have a position from which to observe and critique? Can it present a view of the world marked out with scare quotes? Probably not, at least in its original form. And yet that form has been the subject of so much creative work, so much adaptation to other purposes, it may be easier for you to think of the Snellen chart as an organizational template for commentary on—and by means of—typography than as a diagnostic tool for medical professionals. Snellen invented a chart but created a meme. It doesn’t take much imagination to see the Snellen chart’s autonomous symbols as a concrete poem, not necessarily readable in the way that normal poems are readable, but maybe a typographic event, an intervention about the 122 eye chart possibility of reading poetry, or for that matter reading anything. That, I think, is why the Snellen chart can be implicated in modern poetry. Its elements rearrange familiar lexical markers. It plays with our attention and our capacity to decipher. It’s difficult, and for that reason it’s brief: nothing wears out its welcome like a modernist experiment that doesn’t know when to leave the gallery. E In 1865, at almost exactly the same moment at which Snellen unveiled his table of disappearing letters, the English mathematician Lewis Carroll published Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, one of the most sophisticated works ever written for children. Chapter Three is entitled “A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale.” You may remember that the animals—and Alice herself—are drenched, thanks to Alice’s sea of tears, and need to be dried out. Mouse offers the driest thing he knows, a history of early English kings, but when it fails to please he recites “a sad and long tale” involving a cat called Fury and an unfortunate mouse. Fury proposes they go to court, where the cat will be judge and jury and condemn the mouse to death. The “tale” is shaped on the page like a tail, the slender column of text swerving left and right, the type growing smaller toward the end of the passage, mimicking the narrow conclusion of a mouse’s tale and the slim fate of the mouse itself. The untitled episode, which is sometimes referred to as “The Tale of the Mouse,” is one of the most familiar visual disruptions of printed text in English literature, up there with Eye Poetry 123 the black and marbled pages in Laurence Sterne’s eighteenthcentury proto-modernist novel Tristram Shandy. For the publisher of any edition of Alice, one creative decision is the choice of type size: How much smaller should the tip of the mouse’s tale be than its starting point? With its vigorous triplets—“Fury said to a mouse, That he met in the house, ‘Let us both go to law. I will prosecute you’”—the little poem gobbles up the page’s space. The last word we hear is “death.” But this isn’t the end of the story. The Mouse rebukes Alice for not paying attention, and the whole dream like carnival of the animals withdraws at Alice’s alarming mention of her cat Dinah. The slender, disappearing text of the story, though, can hardly have much more to it; the Mouse-narrator has told us it’s a sad tale, and Fury seems to hold all the cards. It can’t end well. The main event of the tale is, in fact, not narrative but typographic: to read it your eyes have to swerve back and forth. The reader becomes both the mouse, nervously aware of imminent danger, as well as the cat watching the mouse’s every move. The Oxford University Press archive tells us that “Dodgson considered Macmillan’s original printing crude, and around 1880 commissioned a new printing plate from OUP to produce a more elegant image.”4 This is the printing plate of the reset. As the millions of readers who treasure the Wonderland books well know, Carroll’s typographic melodrama is just one of Alice’s endlessly playful up-endings. Alas (a good Victorian word), the performing Mouse never gets to tell 124 eye chart Figure 9.2 Type plate from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. us the rest of the tale of the mouse, a tale that is neither finished nor finishable. If Alice had paid attention and the mouse been allowed to continue, the tale could have gone on, turning again and again, in a series of smaller and smaller lines. We’ll never know. For the mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (if not for his alter ego, the storyteller Eye Poetry 125 Lewis Carroll), the tale might be representing to us an asymptote—a line that approaches but never reaches another line, going on and on into infinity, always closer but never reaching—and doing it in story terms. We can imagine the tale, running like a mouse, and the typography that delivers it to our eyes becoming microscopic, an infinity of twists and turns, letters measured in Angstrom units, disappearing off into what theorists don’t call, but might, a narrative singularity. It may be no more than coincidence that the Snellen chart began to appear amid the orderly splendor of the High Victorian moment, just before Carroll’s disappearing narrative made its way into print. This little poem isn’t the only episode in which Carroll plays cat and mouse with his readers. To borrow the critic Stanley Fish’s classic description of Milton’s narrative strategy in Paradise Lost, Carroll and Snellen are authors of two of the best-known examples of texts that are “self-consuming”: you read them and use them up (Milton wants to save you, Carroll to entertain you, Snellen to find out what you can see). We can also read Alice with Snellen: Carroll’s miniature performance piece is an eye test for the reader, and a test of a different kind for the poor mouse in the story. Alice in Wonderland is a grand if anarchic narrative, organized with the loopy precision of a dream. Snellen’s chart resolutely refuses to tell a story, but it organizes its non-story in an orderly fashion that follows a deliberate and precise trajectory. It’s hierarchical, but not hierarchical 126 eye chart like journalism, where the lede delivers the most important piece of information right at the top (and is spelled that way so we don’t pronounce it like the metal once used to make the newspaper’s type). The eye chart is a different kind of hierarchy, one where the size and consequence are in inverse proportion, with a sweet spot about three-quarters of the way down. It’s more like poetry, where everything is important all the time but where there’s progress to be made, or maybe to be won. A poet like Collins reads the eye chart as a model for making art and bringing it to the public. Is it too much to claim the Snellen diagram as a work of art itself? Eye Poetry 127 128 10 Optical Allusions In a 2009 issue of Vanity Fair, the critic James Wolcott seized upon the eye chart to make a point about screen performance. Bad acting comes in many bags, various odors. It can be performed by cardboard refugees from an Ed Wood movie, reciting their dialogue off an eye chart, or by hopped-up pros looking to punch a hole through the fourth wall from pure ballistic force of personality, like Joe Pesci in a bad mood. I can respect bad acting that owns its own style.1 This, to be clear, is Wolcott offering grudging admiration for genuine bad acting—even acting that seems as if read off an eye chart (what would that look like? uncomprehending line readings, haltingly sounded out?). Maybe Snellen’s legacy should be defended here; television works with cue cards all the time. At least the eye chart does good work when it’s on duty. Besides, Ed Wood’s films are in a category all their own. When it shows up in popular culture in something like its original form, the eye chart is either in a doctor’s office or being used as a punch line, a representative piece of ordinariness that’s meant to lower the tone of its surroundings. In his memoir Alice, Let’s Eat, Calvin Trillin recounts the story of a friend who, on a lecture tour to Kansas City, asks his hosts to take him to Arthur Bryant’s. It’s an establishment, Trillin reports, that “has been identified as the single greatest restaurant in the world.” His friend’s hosts refuse. Trillin diagnoses their embarrassment at the simplicity of the place, “a barbecue joint whose main dining room has no decorations beyond an eye chart.”2 The line is nicely set up, and Trillin’s prose lets you see the undecorated dining room, with all its energies concentrated on the ritual of barbecue. A lone, out-of-date girlie calendar—the sort of thing you might expect at the garage down the street—would have made the point, but eye chart here is unexpected, and funnier. Outside of a diagnostic context, an eye chart can be funny, and other things, too. By the 1940s, the funny papers had taken up the Snellen diagram and made it a gimmick. There are scores of cartoons that show people (usually men) placed in an examining room and asked to identify something on a conspicuously placed Snellen chart. The joke is either in the chart—there’s a message spelled out in the Snellen format, there’s a single letter or symbol repeated over and over, the sizing is wrong—or the joke is in the caption. In 1942 the Saturday Evening Post ran a cartoon in which a red-blooded military recruit strains to read a chart that promises a diagnostic tease, its narrative descending into smaller and smaller type (“I drew her close to me and soon her passionate lips . . . ”). In the era before Don’t Ask, Don’t 130 eye chart Tell, this eye exam was testing for something more than vision strength. There was a time when manliness was one theme in eye chart humor, cartoons of vaudevillian simplicity in which the test is administered by a busty female optometrist. The man in the chair can’t keep his eyes on the chart. There are cartoons in which a pirate is taking an eye test. The chart consists of the letter R, over and over again. The joke may be too easy. There’s even a variant on the pirate eye-test cartoon in which the optometrist says, “This is too easy.” The pirate is as close as humans come to another cartoon genre: the animal eye exam, evidently administered most frequently to dogs. The dog eye exam is, as you might expect, a chart with the words BARK BARK BARK BARK BARK. (The alternative diagnostic is the WOOF WOOF WOOF WOOF WOOF chart.) The dog always gets it right. Note to veterinary optometrists: in the world of cartoons, cats never seem to get their eyes checked. There are cartoons that feature trick eye tests, like the one in which the patient is a goblin, seated in the examining chair and cheats by stretching its neck to bring it flush with the chart itself. There are eye charts that pull in references to other minor monuments of popular culture, like the 1951 sci-fi classic The Day the Earth Stood Still. Michael Rennie played the extraterrestrial Klaatu, who could be recalled from death by means of the command “Klaatu barada nikto.” Those three words are the punch line of an eye chart cartoon. With the now iconic “A long time ago in a galaxy far far away . . .” the opening sequence of George Lucas’s Star Wars Optical Allusions 131 made famous the device of text rolling away from the viewer. Lay those words flat on a poster and they echo the Snellen fade. At least one cartoonist has picked up that cinematic moment, though without going as far as renaming it the Lucas eye chart. There are eye chart cartoons that punish those with terrible handwriting. A Snellen test for doctors mimics the illegible scrawls on a prescription pad; the physician-patient squirms and squints, trying to make sense of the image. As a punishment, consider it Dante lite. E The hypodermic, the thermometer, the x-ray machine, the stethoscope, and the eye chart: these five tools of modern medical treatment show up again and again in the simplest visual narratives. Bring any one of them into the frame and the reader knows immediately the terms of the situation and probably how the joke has to work. Among these five, only the eye chart works with text. And that’s the key to the eye chart’s pervasive visibility. It’s all about the text. Today, online retailers will shower you with all sorts of Snellen-inspired clothing and barware and what might be described optimistically as ophthalmological objets d’art. What these products share is a simple graphic allegiance to the bare-bones elements of the chart’s architecture: rows of text, reducing in size. There are Snellen gift boxes and scarves and clocks, Snellen bill caps and pillows and cups. There are Snellen knee socks with lots of space laying out the eye chart’s symbols. For the baby there are Snellen onesies 132 eye chart and a Snellen teddy bear. If you’re in the market for a kid’s pretend-ophthalmology set (it’s never too early to specialize), a product line called Little Treasures offers a very pink selection of medical tools and resources, including a tiny Tumbling E eye chart. Scaling even further down, there are miniature eye charts to hang on the wall of a dollhouse. Maybe there are even smaller eye charts that dollhouse physicians could give to their dollhouse children to play with, a kind of infinite regress that seems appropriate given the eye chart’s graphic rules. There are Snellen bow ties and key rings. There are Snellenthemed pet accessories, including a Snellen T-shirt for your dog, which has to be a sure-fire conversation starter. You can even walk Fido while sporting your own eye-chart-themed belt buckle. When you saunter into your local Starbucks you might be wearing a Snellen-styled pendant and silver charms engraved with just enough of the eye chart to let the Snellen fan at the next table know that you’re one of them. There are Snellen flip-flops for the vacationer and Snellen tote bags for the recycler. Snellen scarves and ties, Snellen wall clocks, Snellen iPhone covers, and Snellen toilet seats with helpful advice concerning aim and hygiene (all in chart format). The Restoration Hardware interior furnishings shop has given the world a set of shot glasses imprinted with Snellen graphics. Maybe the message is that if you can’t read the chart on your shot glass somebody else will have to drive you home. There is an entire subgenre of “personalized” Snellens— the chart that takes something important in your life, like Optical Allusions 133 Figure 10.1 Bottoms up. Shot glasses with diagnostic benefits. the birth of your child, and lays out name and statistics, according to the diagram’s rules. There are personalized Snellens for couples, layered with names and dates and vows. One needn’t stop at two. There could be personalized Snellens for the members of your barbershop quartet or synchronized swimming team. Any of them would fit nicely on the side of a big coffee mug. There is, in short, a small universe of objects, relationships, and aspirational lists that have been given the Snellen treatment or have “Snellenization” still to come. In the smallest Snellenized objects—ear rings, for instance—we confront Snellen critical mass: the very least you need are three lines of type, arranged in descending order of size. Like 134 eye chart the repetitions in a joke or the questions in a fairy tale, three is the minimal number to make an eye chart work. The Snellen format can even dispense with text altogether and still be recognizable as an eye chart. In these instances, the familiar layout of optotypes has been entirely replaced by other non-narrative elements, often a collection of objects within an identifiably unified class, now arranged in a visual hierarchy. It isn’t always clear that the object at the top of the chart is more important than any other—the image is just set bigger, but the diminished size of subsequent lines reinforces a familiar association. So there are charts of furniture, for example, where a settee might get the E spot, while lines of chairs and such descend visually, though not necessarily in any architectural or chronological order. A chart of animal silhouettes might position a whale as the E creature, which sounds reasonable enough, with an ocean of creatures below it, growing ever smaller. There are Snellen charts of famous buildings and fancy shoes and electric guitars and almost anything else that might be describable in a set of easily representable, discrete images. Many of these exist in poster form, their likely destinations a college dorm or a teenager’s bedroom. Among other non-linguistic eye charts, one counts Pi Snellen, which is composed entirely of numbers. The mathematical constant is an endlessly non-repeating number, but fortunately Pi Snellen limits itself to the classic eleven lines. It even marks off the point where the Snellen chart would indicate 20/20 vision, as if in this case there was Optical Allusions 135 Figure 10.2 The Pi eye chart. anything significant in reading off the calculation of pi to the thirty-sixth place, which falls on line eight. E Some of the most interesting Snellen-based graphics use the heart of the eye chart—the play of letters and the possibility of language—and take it to the next level. These charts—let’s call them Message Snellen—have something to say. Like a bar pour, they can be arranged into two categories: straight up or on the rocks. First, Message Snellen straight up. Take, for example, chart-like compositions that are less about language or 136 eye chart testing or numbers than simple civic pride. Good-spirited graphics promote almost every major city and are nicely printed in white type on black background, suitable for display anywhere pride or nostalgia may be found. You can order them from an outfit called Picture It On Canvas, and for your money you get a city name and key neighborhoods. They’re spaced out in Snellen formation. Most of the words break apart as the letters flow to the next line, so that decoding them is part of the pleasure in recognizing one’s Figure 10.3 Urban geography as cultural eye test. Optical Allusions 137 favorite districts. In this example, Uptown gets the last line, which might suggest that it’s the most exclusive, the least well known, or the hardest to find. The straightforward Message Snellen chart is most suitable for the sincere thought, either polite or enraged, with the design and text selected to complement one another. When urging people to support a cause or adjust their perspective on a social issue, the last thing you want to do is to make them solve a puzzle. A tea towel in a London shop reads: Figure 10.4 The most comforting eye chart ever devised. 138 eye chart “Tea is the finest solution to nearly every catastrophe and conundrum that the day may bring.” No funny business. The tea towel’s appeal is to a reader who wants tea served properly and words spelled completely, and so the eminently British sentiment is treated with graphic respect. Message Snellen can also be educational and compassionate. A handsome WPA-era poster urging young persons to have their eyes checked suggests that “John is not really dull—he may only need to have his eyes examined.” Figure 10.5 Message Snellen and optical understanding. Optical Allusions 139 Young John glances uncertainly, past his open book, at a sheet of paper held by a perhaps exasperated teacher. The text is laid out in a modified Snellen arrangement. Message Snellen can be fully evangelical, too. Like the appeal to understanding for John (who may only need glasses), the religion-themed Snellen shies away from clever, broken orthography in favor of the direct embrace. One example of Evangelical Snellen holds every word intact within its pyramidal lineation, with the exception of the very beginning. The text reads: “Jesus will guide you & me / Worship together / Eternity Devotion Awakening.” The text becomes exceedingly small, and maybe that’s the point, as if to say that following the path will lead you to righteousness, but it will take effort. (See: needle, eye of.) Figure 10.6 Evangelical Snellen. 140 eye chart A footnote for the faithful: those word breaks in Snellen charts aren’t without their perils. For Anglophone readers who also read French there’s the possibility of a momentary double-take in those first two lines—je (the first person singular pronoun) followed by sus, an (admittedly infrequent) form of the verb savoir (to know), so those first two lines weirdly enough also mean I knew. (Yes, but did I see?) The good works of Evangelical Snellen pale, however, before the frat-boy shenanigans of Drunk Snellen. The eye chart is one of graphic design’s gifts to intoxication, or maybe it’s the other way around; Drunk Snellen is Message Snellen’s unattractive neighbor, and he’s been busy. There are a lot of Drunk Snellen designs, most premised on the humor in misspelling or scrambling words, or in finding the bottom of the chart a bunch of letters that won’t stay still. Nothing says “I can’t drive” or “I don’t think this is my room” like an eye chart with deliberately blurred text. Many are crude. Others are just callow in a nerdy way: Figure 10.7 Drunk Snellen. Optical Allusions 141 Picture AM I DRUNK OR ARE YOU GETTING BLURRED? on a T-shirt. The visual punch line falls on the word blurred—small, fuzzy, and located at waist height or below, which may not be where you want anybody reading closely. The counter to Drunk Snellen may be Romantic Snellen, which tends to declarations of earnest devotion with a touch of weep. “I am my beloved and he is my xoxox,” reads one graphic, also available as a pillow. The kisses are quite small. Another Romantic Snellen—“Sometimes the heart sees what is invisible to the eye”—uses the format very well to make its point. It’s very difficult to see that final “eye.” For English speakers, the eye/I pun has been romantic poetry’s ace in the hole at least since Shakespeare’s time. The Bard’s sonnets have eye/I all over them, and although Shakespeare lived before the Snellen chart, his verse still forces us to puzzle out the many ways in which eyes and I’s—seeing and being and being seen—are intimately connected. We are what we see. The modern eye exam negotiates a space between the clinical formality of a nineteenth-century medical graphic and the chaos of the body, between the inorganic abstraction of language and the sometimes all-toopresent reality of the physical forms we occupy. There can’t be a more direct connection between the eye chart and the body than a Snellen tattoo. Tattooing, which writes upon the body, transforms that inorganic abstraction into art upon the skin. Not all tattoos are 142 eye chart made of words, but every tattooed word alters our perception of what writing is and what it’s for. Tattooing changes the relationship of spoken language—instantly vanishing almost as it is born—to the body of the tattooee, now holding inked words in place forever. Snellen straight up is a challenging goal for a tattoo artist: so many lines of text, so much precision—vertical and horizontal spacing, and the special obligation to clarity in the final line. An East Village arm boasts a Snellen chart, editing the eleven lines down to nine. Figure 10.8 Tattoo Snellen. Optical Allusions 143 If you’re going to get inked and want an eye chart as part of your display, you might prefer some form of Message Snellen, maybe a declaration of faith (not quite the same as Evangelical Snellen—it all depends on who gets to see the tattoo). When the eye chart meets the Gospel According to John, the Snellen syntax reformats the Evangelist’s words. On this photographic subject’s body, a slightly shortened version of John 9:25 becomes the Gospel according to John according to Snellen: ONE THING I KNOW THAT I WAS BLIND NOW I SEE. Figure 10.9 Inking belief in Snellen terms. 144 eye chart If faith is a form of second sight, this may be scripture’s most eloquent test for vision beyond vision. E Not long ago, Snellen-style charts were the work of type shop craftsmanship. Now the internet has made the Snellen format available to everyone. There’s a free eye-chart generator you can try for yourself. Following in the digital footsteps of the internet’s popular anagram generator and the Shakespeare insult generator, the website eyechartmaker.com allows you to take Snellen’s format and repurpose it. You get to use twenty-eight letters (fewer than that and the program fills in your last line with default letters). So, for example, I was able to generate this: Figure 10.10 Do-it-yourself Snellen. Optical Allusions 145 And this: Figure 10.11 Do-it-yourself Jaeger. We can all be children of Snellen now, and we can do that because the eye chart has been dematerialized, turned into a way of organizing ideas and delivering them in a package we can immediately recognize. The Snellen diagram is a shape that’s been shifted, turned, dramatized, made to amuse and inspire and even enchant—that’s a lot of work for what began as an arrangement of nine deliberately non-signifying letters with one simple-complex diagnostic objective. 146 eye chart 11 The Bottom Line The eye chart belongs to the world, seriously as a diagnostic tool, earnestly, and sometimes irreverently, as a graphic syntax. Visual testing is not only a possibility but also a right, as visual health is a global issue and one of profound importance. The Himalayan Cataract Project, to single out only one aid organization, works to bring sight to—the phrase is powerfully concise—“the needlessly blind.” You can learn more about their work at cureblindness.org. Unsurprisingly, the problem most powerfully affects those with the fewest resources. In Sudan, Africa’s largest country, medical workers research the prevalence of “low vision,” a term most often used to describe limitations to sight that are not correctable through the usual means of lenses and surgery. Even in Sudan, the Snellen chart has helped move forward our knowledge of the problem and its scale.1 The World Health Organization supports global efforts to identify and combat threats to vision. In this image, a Landolt eye chart stands on a Sudanese village wall as a medical professional administers the exam. Figure 11.1 Eye testing in a Sudanese village. Across the world, hospitals have turned the eye chart into massive public service announcements. In 2012 an enormous banner—seven thousand square feet and claiming to be the world’s largest eye chart—loomed over Bannergatta Road, a busy street in Bengaluru, India, urging people to have their eyes checked. The occasion was “World Sight Day,” and the project a joint venture of the Sankara Eye Hospital and the Sankara College of Optometry. India’s National Programme for the Prevention of Blindness had declared “Eye test for all” as the year’s theme. 148 eye chart Figure 11.2 Snellen as an Indian public service announcement. The enormous eye chart was in English. I AM YOUR EYES, it began, taking no chances that the reader need waste time deciphering the message. Another ad, created by the Waterworks group for the Sankara medical program, took a quite different approach: it arranges elements taken from the “sixty-one languages currently in use in India”—samples of India’s languages transformed into optotypes—and lays them out in Snellen formation. I can’t read the ad, but how many could? There’s something wonderfully Babel-like about the graphic, which juxtaposes the linguistic diversity of Indian culture and the social project of encouraging a widely diverse population to get eye check-ups. The Bottom Line 149 In 2015 a giant Tumbling E eye chart was installed on the side of an eye hospital in Jilin, China. Another hospital in Zhengzhou City has made the Tumbling E, six stories high, the wordless face of its windowless side wall. The Snellen chart has become, through its many descendants, Figure 11.3 Eye-test posters. Tromsø, Norway. 150 eye chart a recognizable tool for social change, and it can do that work on the massive scale of these banners and installations because its function and message are clear. The eye chart’s message works at smaller scale, too. Tromsø, Norway is the world’s most northerly university town. In wintertime it’s also one of the best places on earth to train your eyes on the Northern Lights. If you were to stroll down Tromsø’s main street (which would be hard to avoid) you might stop in front of a shop window displaying this poster. “Test synet ditt,” it reads test your eyesight. It’s a Snellen chart with benefits: the Norwegian text instructs you to stand three meters back (do it carefully—that would probably put you in the road) and read the lines of text. Can’t read the last one? Make an appointment immediately with the optometrist. Snellen lived before the Department of Motor Vehicles became a primary site of vision testing, but this Norwegian chart notates particular lines of text with images of a car and, further down, a truck. You’ll learn that you need to have vision this sharp to get a license to drive, and that sharp if you’re handling a big rig. Travel three and a half thousand kilometers to the south to Ljubljana, Slovenia. It won’t take you long to wander through Stari trg, or the Old Square. At number 21, you will come upon the Galerija Škuc. Since 1978, the Škuc Gallery (pronounced “shkoots”) has been a familiar alternative exhibition space for art and culture, presenting the work of national and international artists. Škuc stands for Študentski Kulturni Center, and the acronym points back to the The Bottom Line 151 organization’s origins. You may mistake the gallery’s sign for that of an optometrist’s shop. Galerija Škuc has Snellenized its address. Pay attention here, it seems to say. E Have we come any closer to knowing what kind of a thing an eye chart is? Something about the eye chart, this inert piece of graphic design, touches upon not only diagnosis but also concepts like visual memory, medicine as magic, the reflection of the self. Some final definitions: Eye chart: Part oracular pronouncement, part hieroglyph, sometimes poem, always picture, the eye chart is the ordinary object that tells us what we think normal looks like. How many other ways of getting that reassurance are there? Your vital signs are within the appropriate range, you live a middle-class life, are of average intelligence, you dream dreams you hope are like everyone else’s. But the eye chart promises something else: the precision of what looks like the right answer. When I was a student my French professor explained that we would be graded on a scale of twenty. The best we could get, he announced, was an 18/20. 19/20 was for le professeur. (Other systems give 19 to the king, but the professor was no royalist.) 20/20 was for Dieu. Getting 20 out of 20 was divine perfection. I doubt Herman Snellen had a French lesson in mind. Eye chart: an object that’s all about lessons—lessons in reading, lessons in discrimination between shapes, in the 152 eye chart Figure 11.4 Snellen as graphic style. A gallery sign in Ljubljana. threshold of diagnosis, in the borders between the machine and the body and between the organic and the appliance. Eye chart: an object, a diagnostic tool, a map of crises, an attitude, a piece of found poetry, a trope of advertising and politics and humor, a message that finally reaches us only when, despite our best efforts, it slips out of sight. Eye chart: A sign in the window we call the world. A test of our limits. The Bottom Line 153 Figure 11.5 [Your answer here.] The British artist Aled Lewis nicely captures the uncapturable of Snellen’s diagram. It won’t help to enlarge the image. You’ll have to make do with the eyes you have. 154 eye chart Acknowledgments T he mild obsession that is this little book would never have happened without the enthusiasm of Chris Schaberg and Ian Bogost and the editorial guidance of Haaris Naqvi at Bloomsbury. More than a decade ago, the short-lived but enthusiastic Group for Early Modern Cultural Studies heard my first attempts—barely a handful of pages— at bridging Daza, Snellen, and cultural studies, after which that material was put into the deep freeze of my hard drive. The opportunity to revive and expand a sketch into a book reminds me of how much fun it is to work on subjects that— to keep with my theme—often lie outside the visual field. I am especially grateful to the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, which made rare materials available, and to the New York Academy of Medicine Library and its librarian, Arlene Shaner. Other institutions were generous with access, materials, and time: the Grolier Club, NYU’s Bobst Library, the Cooper Union Library, and the National Gallery, Washington. The World Health Organization and Oxford University Press supplied photographs. Two generous friends—Hal Sedgwick, professor at the SUNY School of Optometry, and my Cooper Union colleague Alexander Tochilovsky, curator of the Lubalin Center for Typography—were kind enough to read the manuscript. Some years ago, Mario Biagioli pointed me toward the history of Italian telescopy. Julie Park pointed me to eighteenth-century materials. Raffaele Bedarida and Jacques Lezra spot-checked spots. Any lapses in the final text remain, however, my own responsibility. My thanks to Ina Saltz and Aled Lewis for the use of their work, Ben Ross Davis for allowing me to photograph his arm, and to Dr. Paul Runge, who shared with me his deep technical knowledge and, in so doing, reminds us that ephemera is sometimes the name other people use for the fragile things, such as eye charts, that turn out to be really interesting after all. 156 Acknowledgments Notes Chapter 1 1 U.S. Medical Investigator 21 (1885): 301–6. 2 Oxford English Dictionary online, entry “eye,” accessed May 31, 2016. 3 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang,1982), 8. [Orig.1980 as La chambre claire]. Chapter 2 1 See the British Museum online collection site, http://www. britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_ object_details.aspx?objectId=369215&partId=1, accessed May 31, 2016. 2 Aristophanes: Three Comedies, trans. William Arrowsmith (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1977), 59–60, © William Arrowsmith 1961. 3 See Lawrence Weschler, Mr Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder: Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Wonders of Jurassic Technology. Vintage: New York, 1996. 4 http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/college/museyeum/ online_exhibitions/spectacles/invention.cfm, accessed August 14, 2016. 5 http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/college/museyeum/ online_exhibitions/spectacles/invention.cfm, accessed May 28, 2016. 6 D. Graham Burnett, Descartes and the Hyperbolic Quest: Lens Making Machines and Their Significance in the Seventeenth Century, American Philosophical Society 95, part 3 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2005), 9. 7 Vincent Illardi, Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2007), 150. Chapter 3 1 Benito Daza de Valdés, Uso de los antojos para todo genero de vistas (Seville, 1623). 2 Instituto de Óptica “Daza de Valdés” (at C/Serrano 121, Madrid) falls under the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. The Instituto de Óptica was established in 1946. http://www.io.csic.es/IO_en/Presentation.htm. 3 Edward Rosen, “The Invention of Eyeglasses,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1956 (XI: 1): 13–46. 4 Paul E. Runge, MD, “Eduard Jaeger’s Test-Types (Schrift- Scalen) and the Historical Development of Vision Tests,” 158 Notes Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 98 (2000): 375–438. 5 August Colenbrander, MD, “The Historical Evolution of Visual Acuity Measurement,” ResearchGate, 2009, https://www. researchgate.net/publication/232081008_The_Historical_ Evolution_of_Visual_Acuity_Measurement, accessed May 31, 2016. 6 Daza, Uso de los antojos, Dialogue 1, 33. Chapter 4 1 Maria Luisa Righini Bonelli and Albert Van Helden, Divini and Campani: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of the Accademia del Cimento (Florence: Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza di Firenze, 1981), 31, 50. 2 Ibid., 21. 3 Ibid., 32. 4 Ibid., 34. 5 George Adams, Essay on Vision (London, 1792), 98. 6 Runge, (386) points out that this is the only printing of Küchler’s chart. 7 Runge (388), quoting Küchler’s original preface to his Schriftnummerprobe (1843). 8 Michel Meulders, Helmholtz: From Enlightenment to Neuroscience, trans. Laurence Garey (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 105. 9 http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/college/museyeum/ online_exhibitions/optical_instruments/charts.cfm. Notes 159 10 See, for example, Test Chart 2000 (“the first Windows- based computerized test chart in the world”) and its current iteration, Test Chart 2016, from Thomson Software Solutions: http://www.thomson-software-solutions.com/test-chart-xpert3di/. Chapter 5 1 Edmond Landolt, A Manual of Examination of the Eyes, trans. Swan M. Burnett (London, 1879), 17. 2 Sir Thomas Longmore, The Illustrated Optical Manual (London: Longmans, Greene & Co, 1888), 186. 3 C. Devereux Marshall, F.R.C.S., Diseases of the Eyes (New York: William Wood & Company, 1914), 294ff. 4 https://nei.nih.gov/health/color_blindness/facts_about accessed May 6, 2017. 5 An early Snellen stumble: though quickly setting on the letter E, a previous Snellen chart gave pride of place to the letter A. The Istituto Nazionale di Ottica in Florence has an example from 1862. See: Bonelli and Van Helden, 37. 6 Allan Metcalf, “My 20/20 Prediction,” Chronicle of Higher Education, September 2, 2016 http://www.chronicle.com/ blogs/linguafranca/author/ametcalf/. 7 Merriam-Webster Dictionary online, accessed August 9, 2016. 8 August Colenbrander, Duane’s Ophthalmology, ch. 51. 9 Michael F. Marmor, MD, “An Eye Chart for Edgar Degas,” JAMA Ophthalmology, 131:10 (October 2010): 1353–55, accessed online June 8, 2016. 160 Notes 10 Ibid. 11 See Ian Bailey, “New Design Principles for Visual Acuity Letter Charts,” American Journal of Optometry and Physiological Optics 53, I11 (November 1976): 740–45. 12 See Jan E. Lovie-Kitchin, “Is It Time to Confine Snellen Charts to the Annals of History?,” Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 35 (2015), 631–36. 13 George Mayerle, test chart, Schmidt Litho Co, San Francisco, 1907. Courtesy U.S. National Library of Medicine digital collections. Chapter 6 1 Runge, “Eduard Jaeger’s Test-Types,” 392. 2 William F. Norris, MD and Charles A. Oliver, MD, System of Diseases of the Eye 2 (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1900), 28. 3 “Few of the many series of reading test-types published from time to time will compare with the ‘Schrift-scalen’ of Jaeger, published in 1854, for fullness and even grading, and which, from Nos. 1 and 9, practically give a paragraph of reading for each visual angle of one minute from 4’ to 12’, as measured by the short, lower-case letters.” Transactions of the Section on Ophthalmology of the American Medical Association, 1910, 145. 4 Test-Types . . . corresponding to the Schrift-Scalen of Eduard Jaeger (New York: William Wood & Co., 1868). 5 See Le site de la société d’études töpfériennes at www.topfer.ch. 6 Examples taken from the fifth edition of the Optotypi, Notes 161 published in 1875 simultaneously in London, Berlin, New York, and Utrecht. A test-type booklet despite its title, the publication bears Snellen’s name on the title page. Chapter 7 1 D. Hack Tuke, MD, ed., A Dictionary of Psychological Medicine (London: J. A. Churchill, 1892), 290. 2 Ibid. 3 Irving B. Weiner and Roger L Greene, Handbook of Personality Assessment (New York: John Wiley, 2008), 347. Chapter 8 1 William Germano, The Tales of Hoffmann (BFI Film Classics), 2013. 2 H. G. Wells, The Invisible Man: A Grotesque Romance (New York: Dover, 1992), 108. 3 Marcel Proust, “Du côté de Chez Swann,” A la recherche du temps perdu (Paris: Gallimard, 1954), 54. Translation mine. Chapter 9 1 “When I start a poem, I assume the indifference of readers,” Irish Times, August 11, 2014. 162 Notes 2 Alexander Pope, The Works of Alexander Pope, vol. 3 (London, 1778), 297. 3 Phil Rizzuto, O Holy Cow! The Selected Verse of Phil Rizzuto (New York: Harper, 2008); Sam Cohen, The New Yorker, May 29, 2015. 4 http://blog.oup.com/2015/07/alice-wonderland-slideshow/ Mouse tail “stereotype plate” from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a second issue of the first edition of “Alice” photographed by Jack Campbell-Smith for Oxford University Press. Reproduced here by permission. Chapter 10 1 James Wolcott, “I’m a Culture Critic & Hellip; Get Me Out of Here!” Vanity Fair, December 2009. 2 Calvin Trillin, Alice, Let’s Eat: Further Adventures of a Happy Eater (New York: Random House, 2007), 32. Chapter 11 1 Jeremiah Ngondi et al., “Prevalence and Causes of Blindness and Low Vision in Southern Sudan,” PLoS Med, December 2006; 3 (12): e477. Published online December 19, 2006, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030477, accessed August 22, 2016. Notes 163 164 Index Note: Page references for illustrations appear in italics. 20/20 (TV news magazine) 59 20/20 ratio (Snellen fraction) 59–62 accademia 41 Accademia dei Lincei 41–2 Accademia del Cimento 42–4 Adams, George 48 Essay on Vision 48 Age of Discovery 20 Alice, Let’s Eat (Trillin) 130 Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Carroll) 123–6, 125 American Civil War 87 annuit coeptis 29 anteojos 26 antojos 26, 39 Aristophanes 14–15, 37 The Clouds 15 Arthur Bryant’s (restaurant) 130 Assyria 14, 16 astronomy 13–14, 21, 22, 29 As You Like It (Shakespeare) 27 Athens, Greece 14–16 Australia 72 Austria 5, 31 Babylonia 61–2 Backus, Jim 100 Bacon, Francis 29, 30 Sylva Sylvarum, or a Natural History in Ten Centuries 29, 30 Bacon, Roger 18 Bailey-Lovie chart. See logMAR chart Barthes, Roland 7 Camera Lucida 7 Beethoven, Ludwig van 17 Bengaluru, India 148 Berenson, Bernard 95–6 Bethesda, Maryland 25 Bible 96, 118–19, 144, 144 Borneo 20 Braque, Georges 50 Britain 138, 138–9 Army 56–8 Department of Forestry 57 Indian Pilot Service 57 Royal Irish Constabulary 57 Royal Navy 57 British Museum 14, 67 Burnett, D. Graham 20 Busustow, Stephen 100 Calvino, Italo 86–7 If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller 86–7 Camera Lucida (Barthes) 7 Campani, Giuseppe 42–4, 51 Carroll, Lewis 123–6, 125 Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 123–6, 125 Cassatt, Mary 69, 70 Champollion, JeanFrançois 66–7 Christianity 1, 16, 31 Cicero 46 De finibus bonorum et malorum 46 Cincinnati, Ohio 1–2 166 Index Clouds, The (Aristophanes) 15 Cohen, Sam 122 “Sideline Poetry” 122 Collins, Billy 117–18, 127 “Colour-Ignorance Test” 57 Comedy of Errors, The (Shakespeare) 37 Commedia (Dante) 43 connoisseurship 95–6 contact lens. See lens/ lenscrafting contes d’Hoffmann, Les (Offenbach) 105 Conversations with Eckermann (Goethe interviews) 79–80 Coppélia (ballet) 105 Córdoba, Spain 25 Corman, Roger 110–12 X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes 110–12 Cowper, William 35 “The Solitude of Alexander Selkirk” 35 criminology 91–5 Culver City, California 18 Dada 50, 122 Dante 43, 132 Commedia 43 Day the Earth Stood Still, The (Wise) 131 Daza de Valdés, Benito 25–39, 28, 32, 46, 48, 99 Uso de los antojos para todo genero de vistas 25–39, 28, 32, 99 De finibus bonorum et malorum (Cicero) 46 Defoe, Daniel 35 Robinson Crusoe 35 Degas, Edgar 69, 70–2, 71 Scene from the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey 70–2, 71 Delibes, Léo 105 Department of Motor Vehicles 151 Dick and Jane series 51 Dickens, Charles 80–1, 99 Sketches by Boz 81 Dictionary of Psychological Medicine 93 digital humanities 85 diopter 63–4 divine light 28, 29, 30 Divini, Eustachio 42–4, 51 Dodgson, Charles Lutwidge. See Carroll, Lewis do-it-yourself Jaeger 146 do-it-yourself Snellen 145, 145 Donders, Franciscus 5, 52, 55 dream interpretation 96–7, 106 Drunk Snellen 141, 141–2 Duchamp, Marcel 50, 122 Fountain 122 Du côté de chez Swann (Proust) 113–14 Early Modern world 37–9, 41 “Easter Wings” (Herbert) 119, 120, 122 EDTRS (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study) chart 74 Edwardian era 57 Egypt 14 Egyptian style 65–6 Egyptomania 66 El Greco 70 Eliot, T. S. 84 England 38, 42, 46–7, 47, 56 Royal Society 42 Essay on Vision (Adams) 48 Europe 20, 41, 50, 58, 66, 78 eyechartmaker.com 145, 145, 146 eye/eyesight 18 20/20 ratio 59–62 aging 20, 25, 27, 31, 103 and art 69–72, 71, 95–6 artificial eye 103–5 astigmatism 9–10, 63, 92 blindness 10, 34, 103–4, 106, 147, 148 Index 167 blur 64, 65 cataract 69, 72, 99, 147 color blindness 57–8 correction 62–4 criminology 93–5 farsightedness 9, 37, 63 floater 10 focus 64 gender 31, 58 and health 74 lens 99 light pollution 13 looking and seeing 18, 21–2, 27 macular degeneration 10 nearsightedness 9, 20, 33, 63, 99–101, 100 optic nerve 53 peripheral vision 10 presbyopia 9 pressure 10 pseudo-isochromatism 58 reading 18–19, 34–5, 43–4, 48–51, 56, 77–89, 79, 80, 83, 117–23, 120, 124–7, 152 retina 10, 21, 53, 74, 99 sharpness 91–6, 152 social impact 35–9 and the soul 46–7, 47 strength 48, 63, 92 168 Index technology 17–18, 21–2, 27–9, 33–6, 39, 41–4, 47–54, 49, 50, 55–64 terror 103–10, 107 vision theory 27–9 visual field 10, 61–3 eyeglasses 3, 13, 18, 19–21, 26–27, 28, 33–6, 38, 39, 41, 47, 48, 57, 62–4, 91, 99 Fantastic Voyage (Fleischer) 114–15 Fish, Stanley 126 Fleischer, Richard Fantastic Voyage 114–15 Florence, Italy 42–3 “Flower, The” (Herbert) 119–20 “Flowers for Algernon” (Keyes) 98 Folger Shakespeare Library 25 “Forsythia” (Solt) 121–2 Foucault, Michel 95 Fountain (Duchamp) 122 Francis of Assisi 118–19 Freud, Sigmund 65, 96–7, 104, 106 The Interpretation of Dreams 96–7, 106 “The Uncanny” 104 Galerija Škuc 151–2, 153 Galileo 21–2, 39, 41, 42 Sidereus Nuncius 21 Germany 31, 49–52, 74, 79–80, 87 Gilded Age 95 Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von 79, 79–81 Conversations with Eckermann (interviews) 79–80 Google Earth 115 graphic design 3, 6–7, 9, 11, 32, 32, 33, 44, 52, 53, 55–61, 64–5, 68–9, 69, 73, 73–5, 75, 82–3, 83, 132–46, 134, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 152, 153 Great Seal of the United States 29 Gutenberg, Johannes 82 Herbert, George 119–22 “Easter Wings” 119, 120, 122 “The Flower” 119–20 hieroglyph 66–7, 152 Himalayan Cataract Project 147 Histoire de M. Vieux Bois (Toepffer) 87 Hitchcock, Alfred 104 Vertigo 104 Höch, Hannah 50 Hoffmann, E. T. A. 103–5 The Nutcracker 103 “The Sandman” 103–5 Homeopathic Medical Society of Ohio 1–2 Hooke, Robert 39 House Beautiful 19 hyperopia. See eye/eyesight; farsightedness hypodermic 132 Hammurabi 62 Harry Potter series (Rowling) 114 heimlich/unheimlich 104 Heine, Heinrich 87 Helmholtz, Hermann von 52–3 Henry V (Shakespeare) 27 Henry VI Part 2 (Shakespeare) 27 If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller (Calvino) 86–7 illuminated manuscript 17, 18 Impressionism 69–70 India 149 National Programme for the Prevention of Blindness 148–9, 149 Interpretation of Dreams, The (Freud) 96–7, 106 Index 169 invisibility 110–15 Invisible Man, The (Wells) 106–8 Invisible Man, The (Whale) 107, 107 Irish Times 117 Ishihara, Shinobu 58 Italian Renaissance 95 Italy 18, 20–2, 41–4, 51, 80, 87 Jaeger, Eduard 5–7, 65, 77–83, 79, 80, 83, 85–6, 88 reading card and testtype 5–7, 77–83, 79, 80, 83, 85–9, 146 Japan 57–8 Jilin, China 150 Johns Hopkins University Low Vision Institute 73 Judaism 13 Kafka, Franz 103 Kansas City, Missouri 130 Keaton, Buster 99 Kepler, Johannes 21 Keyes, Daniel 98 “Flowers for Algernon” 98 Kircher, Athanasius 66 klecksography 97–8 Küchler, Heinrich 49, 49–52, 50, 55 170 Index Laennec, René 53 Landolt, Edmond 68–70, 69 Landolt C chart 68–9, 69, 147 Latin language 44–5, 87 Leeuwenhoek, Antonie van 22 LensCrafters 16–17 lens/lenscrafting 14–17, 19–20, 22, 25, 27–37, 39, 41–4, 47–8, 55, 92 Lewis, Aled 154 Lisbon, Portugal 26 literacy 8, 16, 20–1 Lithuania 95 Little Treasures 133 Ljubljana, Slovenia 151–2, 153 L.L. Bean 32 logMAR chart 72–3, 73, 74 Lombroso, Cesare 92–6 L’uomo delinquente 92–5 London, England 67 London College of Optometrists 18 Lord of the Rings, The (Tolkien) 114 lorem ipsum 45–6 Lucas, George 131–2 Star Wars 131–2 L’uomo delinquente (Lombroso) 92–5 McClintock, Richard 46 Madrid, Spain 25, 26 Magellan, Ferdinand 20 Magic Schoolbus (series) 115 magnification 13–16, 18, 26, 39 Marmor, Michael 70–2 Masonic eye 29 Mayerle, George 74 Mayerle eye chart 74, 75 Metternich, Klemens von 77 Metz, Christian 114 Meulders, Michel 53 microscope 18, 22, 39, 42, 115 mie prigioni, Le (Pellico) 87 Milland, Ray 110, 111 Milton, John 21–2, 126 Paradise Lost 22, 126 miniature/micro miniature 17, 18 modernism 13, 17, 39, 50, 65, 114, 122, 123 Monet, Claude 69, 70 Morelli, Giovanni 95 Morgenthal Frederics 34 Motley, John Lothrop 88 Mr. Magoo 99–101, 100, 110 Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol (TV special) 99 Museum of Jurassic Technology 18 myopia. See eye/eyesight; nearsightedness nanorobotics 114–15 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC 70 National Library of Medicine 25 National Vision Research Institute of Australia 72 logMAR chart 72–4, 73 Nederlandsch Gasthuis voor Ooglijders 5 Netherlands 2, 5, 31, 41, 87, 88 New Orleans, Louisiana 1, 137 Newton, Isaac 39, 41 New York Academy of Medicine Library 78 New York City 34, 81 New Yorker 122 Nimrud Lens 14 Norway 14, 151 Nuremberg Chronicle (Schedel) 20 Nutcracker, The (Hoffmann) 103 Offenbach, Jacques 105 Les contes d’Hoffmann 105 Old Masters 19, 95 ophthalmology 4–6, 24–5, 39, 52, 55–64, 69, 70, 99, 119, 132 Index 171 ophthalmoscope 52–3 opkomst en bloei der Vereenigde Nederlanden, De (Styl) 87 optician 6, 16, 34, 42, 48 optometer 23–4, 24 optometry 6, 17, 21, 25, 34, 47–8, 53, 110, 131, 151 optotype 65–6, 78, 135, 149 Orientalism 66 Oscar award 100 Oulipo group 86 Oxford English Dictionary 2, 7 Oxford University Press 124 Paradise Lost (Milton) 22, 126 Parker, Dorothy 60 Paul, Jean 79 Pellico, Silvio 87 Le mie prigioni 87 Perec, Georges 86 A Void 86 Petrarch 43 Philip IV, King of Spain 38 photography 7, 99 Picasso, Pablo 50 Picture It On Canvas 137 Plato 37, 114 Symposium 37 Plautus 37 poetry 22, 43–4, 117–23, 120, 127, 153 172 Index Pope, Alexander 120–1 Powell, Michael 105–6 The Tales of Hoffmann 105–6 Pressburger, Emeric 105–6 The Tales of Hoffmann 105–6 Proust, Marcel 113–14 A la recherche du temps perdu 113 Du côté de chez Swann 113–14 Psychodiagnostik (Rorschach) 97 psychological testing 96–9 publishing 44–6 lorem ipsum 45–6 Pulte Medical College, Cincinnati 1 Rains, Claude 107, 107 reading 7, 20, 77–89, 79, 80, 83, 117–27, 120, 152 reading card 5–6, 7, 77–83, 79, 80, 83, 85–6 reading stone 14, 17, 18, 27 recherche du temps perdu, A la (Proust) 113 Reformation 20 Renaissance 18–19 Rennie, Michael 131 Restoration Hardware 133, 134 Richards, I. A. 84 Rickles, Don 111 Ring der Nibelungen, Der (Wagner) 114 Risorgimento 87 Rizzuto, Phil 122 Robert Marc 34 Robinson Crusoe (Defoe) 35 Rome, Italy 14, 16, 26, 42–3 Röntgen, William 106, 108 Rorschach, Hermann 97–8 Psychodiagnostik 97 Rorschach test 97–9 Rorschach: The Inkblot Party Game 98 Rosetta Stone 66–7 Rowling, J. K. 114 Harry Potter series 114 Saint Ambrose; Saint Jerome 19 “Sandman, The” (Hoffmann) 103–5 San Francisco, California 74 Sankara College of Optometry, India 148 Sankara Eye Hospital, India 148 Saturday Evening Post 130 Scene from the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey (Degas) 70–2, 71 Schedel, Hartmann 20 Nuremberg Chronicle 20 Schiller, Friedrich 79, 80, 80, 81 Schrift-scalen. See test-type Scientific Revolution 29 screen performance 129, 131–2 self-regulating individual 39 Seneca 16 Seville, Spain 25, 26 Shakespeare, William 17, 25, 27, 37, 118, 142 As You Like It 27 The Comedy of Errors 37 Henry V 27 Henry VI Part 2 27 The Winter’s Tale 27 Sharper Image 91 Shearer, Moira 105 “Sideline Poetry” (Cohen) 122 Sidereus Nuncius (Galileo) 21 Silverman, Kaja 9 Simon, Neil 37 Sketches by Boz (Dickens) 81 Sloan, Louise 73 Sloan (typeface) 73 Snellen, Herman 2, 4–6, 7, 11, 11, 32, 44, 52, 55–61, 64–9, 81–2, 85, 129, 152 Egyptian Paragon 65–6, 67 Snellen chart 2–5, 7–11, 11, 20, 32, 41, 44, 48, 50, 52–61, 64–8, 72, 73, 75, Index 173 83, 85–6, 91–2, 93–5, 99, 109, 111, 117–18, 122–3, 126–7, 129–30, 129–46, 134, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 143, 144, 145, 147–54, 148, 149, 150, 153, 154 Snellen fraction (20/20 ratio) 59–62 Snellenization 132–5 Snellen meme Drunk Snellen 141, 141–2 Evangelical Snellen 140, 140–1, 144, 144–5 Message Snellen 136–46, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 143, 144, 145, 146, 154 Pi Snellen 135–6, 136 Romantic Snellen 142 Tattoo Snellen 142–4, 143, 144 Sokrates 15 “Solitude of Alexander Selkirk, The” (Cowper) 35 Solt, Mary Ellen 121 “Forsythia” 121–2 Sorbonne, Paris 68 Spain 31, 33–4, 38 Spanish Inquisition 25 spectacles. See eyeglasses Spicy Mystery Stories (pulp series) 112 Starbucks 133 174 Index Star Wars (Lucas) 131–2 Sterne, Laurence 124 Tristram Shandy 124 stethoscope 53, 132 Stevens, Wallace 117 Strepsiades 15 Styl, Simon 87 De opkomst en bloei der Vereenigde Nederlanden 87 Sudan, Africa 147, 148 Superman 109, 109–12 Sylva Sylvarum, or a Natural History in Ten Centuries (Bacon) 29, 30 Symposium (Plato) 37 Tacitus 87 Tales of Hoffmann, The (Powell, Pressburger) 105–6 telescope 8, 21, 22, 39, 41–4 test-type 77–83, 79, 80, 83, 85–9 thermometer 132 Toepffer, Rodolphe 87 Histoire de M. Vieux Bois 87 Tokyo, Japan 34, 58 Tolkien, J. R. R. 114 The Lord of the Rings 114 Tommaso da Modena 18 Treviso, Italy 18 Trillin, Calvin 130 Alice, Let’s Eat 130 Tristram Shandy (Sterne) 124 Tromsø, Norway 150, 151 Tudor dynasty 38 Tumbling E Chart 68 typography 11, 44–6, 49, 50, 64–75, 67, 69, 73, 75, 77–83, 79, 80, 83, 121–7, 125, 145 Egyptian Paragon 65–6, 67 Fraktur 49, 50, 50, 74, 75 Landolt C 68–9, 69 “Uncanny, The” (Freud) 104 United States National Institutes of Health 58 poet laureate 117 WPA 139, 139–40 UPA (animation group) 99. See also Mr. Magoo Uso de los antojos para todo genero de vistas (Daza de Valdés) 25–39, 28, 32, 99 Utrecht, Netherlands 2, 4–5, 55 Vanity Fair 129 Varner, Helen 1–2 Venice, Italy 25 Vertigo (Hitchcock) 104 Victorian era 56, 126 Vienna, Austria 78, 96, 97 vision. See eye/eyesight vision statement 59 visual categorization 91–6 visual testing as cartoon 130–2 eugenics 92–5 global health and social change 147–52, 148, 149, 150 graphic design 3, 6–7, 9, 11, 32, 32, 33, 44, 52, 53, 55–61, 64–5, 68–9, 69, 73, 73–5, 75, 82–3, 83, 132–46, 134, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 152, 153 history 27–37, 38, 48–64, 49, 50, 68–9, 74–5, 87–9, 92–8, 106 literacy 56 logarithm 72 magnification 64 mathematics 60–2 measurement 4, 8, 10, 13–14, 22, 38, 55, 63, 91–2 memory and repetition 51–3, 55 merchandising 132–5, 134, 153 military objective 56–7 Index 175 object as 118–19 photography 92–5 popular culture 131–5, 134, 142–6, 143, 144 prescription 62–4 reading card 5–7, 77–83, 79, 80, 83, 85–6 Snellen chart 2–11, 11, 20, 32, 41, 44, 48, 50, 52, 53–61, 64–7, 68, 72, 73, 75, 83, 85–6, 91–2, 93–5, 99, 109, 111, 117–18, 122–3, 126–7, 129–30, 147–54, 148, 149, 150, 153, 154 standardization 5–7, 55 technology 8, 11, 15, 16–17, 23, 24, 31–2, 34, 39, 48–64, 49, 50, 70–5, 73, 75, 77–86, 79, 80, 83, 112–13 test-type 77–83, 79, 80, 83, 85–9 text as 117–23, 120, 125, 126–7, 132 tonometry 10 visual field test 10, 61–2 x-ray 113–14 Void, A (Perec) 86 Wagner, Richard 17, 114 Der Ring der Nibelungen 114 176 Index Walt Disney Company 99 Watchmen (graphic novel series) 98 Waterworks 149 Welch, Raquel 115 Wells, H. G. 106–8 The Invisible Man 106–8 Whale, James The Invisible Man (film) 107, 107 Wieland, Christoph Martin 79 Winter’s Tale, The (Shakespeare) 27 Wise, Robert The Day the Earth Stood Still 131 Wolcott, James 129 Wood, Ed 129 World Health Organization 147 World Sight Day 148 World War I 57–8 World War II 109 X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (Corman) 110–12 x-ray 106, 108–15, 132 Zhengzhou City, China 150