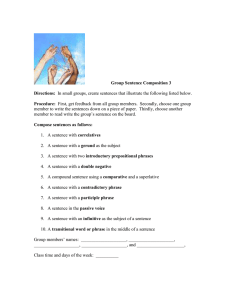

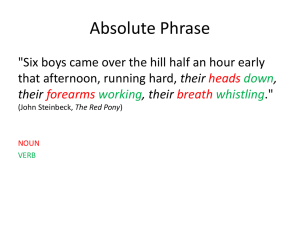

Note Taking Introduction to English Linguistics (Group 2) The Sentence Patterns on Language What the Syntax Rules do? The rules of syntax combine words into phrases and phrases into sentences. Among other things, the rules specify the correct word order for a language. 1. The President nominated a new Supreme Court justice. (grammatical) 2. President the new Supreme justice Court a nominated. (ungrammatical) A second important role of syntax is to describe the relationship between the meaning of a particular group of words and the arrangement of those words. The rules of syntax also specify the grammatical relations of a sentence, such as subject and direct object. The syntax rules specify that a verb like found must be followed by something, and that something cannot be an expression like quickly or in the house but must be like the ball. Our syntactic knowledge crucially includes rules that tell us how words form groups in a sentence, or how they are hierarchically arranged with respect to one another. Syntactic rules reveal the grammatical relations among the words of a sentence as well as their order and hierarchical organization. They also explain how the grouping of words relates to their meaning, such as when a sentence or phrase is ambiguous. What Grammatically is not Based on Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. This is a very interesting sentence, because it doesn’t seem to mean anything coherent, but it sounds like an English sentence. Importantly, a person’s ability to make grammaticality judgments does not depend on having heard the sentence before. People are able to understand, produce, and make judgments about an infinite range of sentences, most of which they have never heard before. We showed that the structure of a sentence contributes to its meaning. However, grammaticality and meaningfulness are not the same things, as shown by the following sentences: Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. A verb crumpled the milk. Although these sentences do not make much sense, they are syntactically well-formed. There are also sentences that we understand even though they are not well-formed according to the rules of syntax. Sentence Structure Sentence structure refers to the way that words are arranged to form a grammatically correct and meaningful sentence. It involves understanding the different parts of a sentence, such as the subject, verb, object, and any modifiers or complements. For example: The child found a puppy. Constituents and constituency tests The natural groupings or parts of a sentence are called constituents. Various linguistic tests reveal the constituents of a sentence. 1. The first test is the “stand-alone” test. If a group of words can stand alone, they form a constituent. 2. The second test is “replacement by a pronoun.” Pronouns can substitute for natural groups. 3. A third test of the constituency is the “move as a unit” test. If a group of words can be moved, they form a constituent sentence. Syntactic Categories 1. Noun phrase (NP): may function as the subject or as an object in a sentence. NPs often contain a determiner (like a or the) and a noun, but they may also consist of a proper name, a pronoun, a noun without a determiner, or even a clause or a sentence. For examples, John found the puppy; The puppy loved John 2. Verb Phrase (VP): always contains a verb (V), and it may contain other categories, such as a noun phrase or prepositional phrase (PP), which is a preposition followed by an NP, such as in the park, on the roof, with a balloon. Lexical and Functional Categories Syntactic categories include both phrasal categories such as NP, VP, AdjP (adjective phrase), PP (prepositional phrase), and AdvP (adverbial phrase), as well as lexical categories such as noun (N), verb (V), preposition (P), adjective (Adj), and adverb (Adv). Each lexical category has a corresponding phrasal category. Because of the difficulties involved in specifying the precise meaning of lexical categories, we do not usually define categories in terms of their meanings, but rather on the basis of their syntactic distribution (where they occur in a sentence) and morphological characteristics. Phrase Structure Trees and Rules A PS tree is a formal device for representing the speaker’s knowledge of the structure of sentences in his language, as revealed by our linguistic intuitions. PS rules capture the knowledge that speakers have about the possible structures of a language. Rather, a speaker’s knowledge of the permissible and impermissible structures must exist as a finite set of rules that generate a tree for any sentence in the language. The Infinity of Language: Recursive Rules The number of sentences in a language is infinite and languages have various means of creating longer and longer sentences, such as adding an adjective or a prepositional phrase. For example; This is the farmer sowing the corn, that kept the cock that crowed in the morn, that waked the priest all shaven and shorn…. Recursive rules are of critical importance because they allow the grammar to generate an infinite set of sentences. This shows how the syntax permits structures with multiple PPs (Prepositional Phrase), For example, in the sentence “The girl walked down the street with a gun toward the bank.” Another option open to the VP is to contain or embed a sentence. NPs can also contain PPs recursively. The PS rules define the allowable structures of the language, and in so doing make predictions about structures that we may not have considered when formulating each rule individually. Heads and Complements Phrase structure trees also show relationships among elements in a sentence. For example, the subject and direct object of the sentence can be structurally defined. The head of a phrase is the word whose lexical category defines the type of phrase: the noun in a noun phrase, the verb in a verb phrase, and so on. Every VP contains a verb, which is its head. The VP may also contain other categories, such as an NP or CP (complementizer phrase). Those categories are complements; they complete the meaning of the phrase. The head-complement relation is universal. All languages have phrases that are headed and that contain complements. Other examples of complements are illustrated in the following examples: head in italics the complement underlined an argument over jelly beans (PP complement to noun) his belief that justice will prevail (CP complement to noun) Structural Ambiguities Certain kinds of ambiguous sentences have more than one phrase structure tree, each corresponding to a different meaning. The sentence ”The boy saw the man with the telescope” is structurally ambiguous. Sentence Relatedness Another aspect of our syntactic competence is the knowledge that certain sentences are related to one another, such as the following examples: The boy is sleeping. (declarative sentence) Is the boy sleeping? (yes-no questions) These sentences describe the same situations. The only actual difference in meaning between these sentences is that one asserts situations and the other asks for confirmation of situations. Transformational Rules Phrase structure rules do not account for the fact that certain sentence types in the language relate systematically to other sentence types. The standard way of describing these relationships is to say that the related sentences come from a common underlying structure. Here are a few more example: The boy is sleeping. Is the boy sleeping? The boy has slept. Has the boy slept? Many sentence types are accounted for by transformations, which can alter phrase structure trees by moving, adding, or deleting elements. The Structural Dependency of Rules Another rule of English allows the complementizer that to is omitted when it precedes an embedded sentence but not a sentence that appears in subject preposition. Agreement rules are also structured dependent. In many languages, including English, the verb must agree with the subject. Further Syntactic Dependencies Sentences are organized according to two basic principles: 1. Constituent structure: refers to the hierarchical organization of the subparts of a sentence, and transformational rules are sensitive to it. 2. Syntactic dependencies: the presence of a particular word or morpheme can be contingent on the presence of some other word or morpheme in a sentence. UG Principle and Parameters According to this theory, there are certain grammatical rules and structures that are hard-wired into our brains, which allow us to learn and use language. Universal Grammar principles are the underlying rules or structures that are believed to be innate in humans and form the basis of our ability to acquire and use language. Languages may have different word orders within the phrases and sentences. UG specifies the structure of a phrase. Sign Language Syntax Sign language syntax refers to the grammatical rules and structures that govern the organization and use of signs in sign language. Just like spoken languages, sign languages have their own unique syntax, which includes rules for word order, sentence structure, and the use of grammatical markers. Signed languages have phrase structure rules that provide hierarchical structure and order constituents.