Learning in Development Partnerships: Global Citizen Competencies

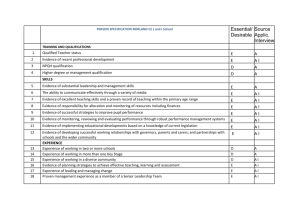

advertisement