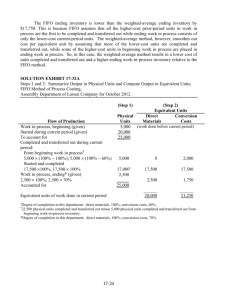

www.downloadslide.com 17 Process Costing Many companies use mass-production techniques to produce identical or similar units of a product or service: Apple (smartphones), Coca-Cola (soft drinks), Chevron (gasoline), JPMorgan Chase (processing of checks), and Novartis (pharmaceuticals). Managerial accountants at companies like these use process costing because it helps them (1) determine how many units of the product the firm has on hand at the end of an accounting reporting period, (2) evaluate the units’ stages of completion, and (3) assign costs to units produced and in inventory. As you learned in your financial accounting class, there are several methods for inventory valuation; the choice of method results in different operating income and affects the taxes a company pays and the performance evaluation of managers. During times of sizable changes in price levels, as has been the case recently with commodities, the impact of using a particular method of inventory valuation can be substantial. Haynes suffers as nickel Prices DroP1 In January 2016, commodity prices tumbled to a 25-year low. The price collapse, Learning Objectives 1 Identify the situations in which process-costing systems are appropriate 2 Understand the basic concepts of process costing and compute average unit costs 3 Describe the five steps in process costing and calculate equivalent units 4 Use the weighted-average method and the first-in, first-out (FIFO) method of process costing 5 Apply process-costing methods to situations with transferred-in costs 6 Understand the need for hybridcosting systems such as operation costing the worst in a generation, was driven in part by a sudden slowdown in demand from China. It affected a wide range of commodities, including crude oil, copper, iron ore, and nickel. For companies that extract and sell commodities, the impact was dramatic. For example, BHP Billiton Ltd., the world’s largest mining company, recorded a loss of $6.4 billion in 2015–2016, the first annual loss in its history. Interestingly, the impact of this price reduction has also been significant for companies that use commodities in their production processes. Consider Haynes International, a leading developer, manufacturer, and marketer of technologically advanced high-performance alloys. Haynes—which operates in the aerospace, power generation, and chemical processing industries—specializes in corrosion-resistant, high-temperature alloys based on nickel and cobalt. The steep decline in the market price of nickel over fiscal 2015 and the first quarter of fiscal 2016 had an adverse impact on the company’s financial results. In May 2016, Haynes reported that relative to the same quarter in 2015, its net revenues dropped by 26.1%, while its gross margin as 1 Roberta Sherman/Pearson Education, Inc. Source: “Haynes International, Inc. Reports Second Quarter Fiscal 2016 Financial Results,” https://globenewswire.com/ news-release/2016/05/05/837154/0/en/Haynes-International-Inc-Reports-Second-Quarter-Fiscal-2016-Financial-Results. html; “BHP Suggests Worst Is Over After Posting Record Loss,” Bloomberg, August 16, 2016. 675 www.downloadslide.com a percentage of net revenue declined from 20.1% to 8.7%. As a result, Haynes recorded a loss for the quarter, compared to a profit in 2015. The reason, according to president and CEO Mark Comerford, was that the “mismatch between market nickel price levels and nickel in cost of goods sold negatively impacted gross margins.” In particular, “falling nickel prices create compression on gross margins due to pressure on selling prices from lower nickel prices, combined with higher cost of sales as the company ships the higher-cost inventory acquired in a prior period with higher nickel prices.” The company values inventory utilizing the first-in, first-out (FIFO) inventory costing methodology. In a period of decreasing raw material costs, the FIFO inventory valuation method results in higher costs of sales as compared to other methods, such as weighted-average or last-in, first-out (LIFO). Looking ahead, Haynes expects the mismatch between market price levels and the nickel in cost of goods sold to persist for at least another quarter. Assuming nickel market prices stabilize, the company anticipates that the compression would be alleviated by the fourth quarter of 2016. Similar to Haynes and other organizations that are engaged in processing commodities, firms such as Kellogg (cereals), and AB InBev (beer) produce many identical or similar units of a product using mass-production techniques. The focus of these companies on individual production processes gives rise to process costing. This chapter describes how companies use processcosting methods to determine the costs of products or services and to value inventory and the cost of goods sold. Illustrating Process Costing Learning Objective 1 Identify the situations in which process-costing systems are appropriate . . . when masses of identical or similar units are produced Before examining process costing in more detail, let’s briefly review the distinction between job costing and process costing explained in Chapter 4. Job-costing and process-costing systems are best viewed as ends of a continuum: Job-costing system Process-costing system Distinct, identifiable units of a product or service (for example, custom-made machines and houses) Masses of identical or similar units of a product or service (for example, food or chemicals) In a process-costing system, the unit cost of a product or service is obtained by assigning total costs to many identical or similar units of output. In other words, unit costs are calculated by dividing total costs incurred by the number of units of output from the production process. In a manufacturing process-costing setting, each unit receives the same or similar amounts of direct material costs, direct manufacturing labor costs, and indirect manufacturing costs (manufacturing overhead). The main difference between process costing and job costing is the extent of averaging used to compute the unit costs of products or services. In a job-costing system, individual jobs use different quantities of resources, so it would be incorrect to cost each job at the same average production cost. In contrast, when identical or similar units of products or services are mass-produced rather than processed as individual jobs, process costing is used to calculate an average production cost for all units produced. Some processes such as clothes manufacturing have aspects of both process costing (the cost per unit of each operation, such as cutting or sewing, is identical) and job costing (different materials are used in different batches of clothing, say, wool versus cotton). The final section in this chapter describes “hybrid” costing systems that combine elements of both job and process costing. Consider the following example: Suppose that Pacific Electronics manufactures a variety of cell phone models. These models are assembled in the assembly department. Upon completion, units are transferred to the testing department. We focus on the assembly department www.downloadslide.com Case 1: ProCess Costing with no Beginning or ending work-in-ProCess inventory 677 process for one model, SG-40. All units of SG-40 are identical and must meet a set of demanding performance specifications. The process-costing system for SG-40 in the assembly department has a single direct-cost category—direct materials—and a single indirect-cost category—conversion costs. Conversion costs are all manufacturing costs other than direct material costs, including manufacturing labor, energy, plant depreciation, and so on. As the following figure shows, direct materials, such as a phone’s processor, image sensors, and microphone, are added at the beginning of the assembly process. Conversion costs are added evenly during assembly. The following graphic represents these facts: Conversion costs added evenly during process Assembly Department Transfer Testing Department Direct materials added at beginning of process Process-costing systems separate costs into cost categories according to when costs are introduced into the process. Often, as in our Pacific Electronics example, only two cost classifications—direct materials and conversion costs—are necessary to assign costs to products. Why only two? Because all direct materials are added to the process at one time and all conversion costs generally are added to the process evenly through time. Sometimes the situation is different. 1. If two different direct materials—such as the processor and digital camera—are added to the process at different times, two different direct materials categories would be needed to assign these costs to products. 2. If manufacturing labor costs are added to the process at a different time compared to other conversion costs, an additional cost category—direct manufacturing labor costs—would be needed to assign these costs to products. We illustrate process costing using three cases of increasing complexity: ■ ■ ■ Case 1—Process costing with zero beginning and zero ending work-in-process inventory of SG-40. (That is, all units are started and fully completed within the accounting period.) This case presents the most basic concepts of process costing and illustrates the averaging of costs. Case 2—Process costing with zero beginning work-in-process inventory and some ending work-in-process inventory of SG-40. (That is, some units of SG-40 started during the accounting period are incomplete at the end of the period.) This case introduces the five steps of process costing and the concept of equivalent units. Case 3—Process costing with both some beginning and some ending work-in-process inventory of SG-40. This case adds more complexity and illustrates the effects the weightedaverage and first-in, first-out (FIFO) methods have on the cost of units completed and the cost of work-in-process inventory. DecisiOn Point Under what conditions is a process-costing system used? Learning Objective Case 1: Process Costing with No Beginning or Ending Work-in-Process Inventory Understand the basic concepts of process costing and compute average unit costs On January 1, 2017, there was no beginning inventory of SG-40 units in the assembly department. During the month of January, Pacific Electronics started, completely assembled, and transferred 400 units to the testing department. . . . divide total costs by total units in a given accounting period 2 www.downloadslide.com 678 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing Data for the assembly department for January 2017 are as follows: Physical Units for January 2017 Work in process, beginning inventory (January 1) Started during January Completed and transferred out during January Work in process, ending inventory (January 31) 0 units 400 units 400 units 0 units Physical units refer to the number of output units, whether complete or incomplete. In January 2017, all 400 physical units started were completed. Total Costs for January 2017 Direct materials costs added during January Conversion costs added during January Total assembly department costs added during January $32,000 24,000 $56,000 Pacific Electronics records direct materials costs and conversion costs in the assembly department as these costs are incurred. The cost per unit is then calculated by dividing the total costs incurred in a given accounting period by the total units produced in that period. So, the assembly department cost of an SG-40 is $56,000 , 400 units = $140 per unit: Direct materials cost per unit ($32,000 , 400 units) Conversion costs per unit ($24,000 , 400 units) Assembly department cost per unit DecisiOn Point How are average unit costs computed when no inventories are present? 3 Learning Objective Describe the five steps in process costing . . . to assign total costs to units completed and to units in work in process and calculate equivalent units . . . output units adjusted for incomplete units Case 1 applies whenever a company produces a homogeneous product or service but has no incomplete units when each accounting period ends, which is a common situation in servicesector organizations. For example, a bank can adopt this process-costing approach to compute the unit cost of processing 100,000 customer deposits made in a month because each deposit is processed in the same way regardless of the amount of the deposit. Case 2: Process Costing with Zero Beginning and Some Ending Work-in-Process Inventory In February 2017, Pacific Electronics places another 400 units of SG-40 into production. Because all units placed into production in January were completely assembled, there is no beginning inventory of partially completed units in the assembly department on February 1. Some customers order late, so not all units started in February are completed by the end of the month. Only 175 units are completed and transferred to the testing department. Data for the assembly department for February 2017 are as follows: $ $ 80 60 $140 Work in process, beginning inventory (February 1) Started during February Completed and transferred out during February Work in process, ending inventory (February 28) Degree of completion of ending work in process Total costs added during February % & Physical Units (SG-40s) (1) 0 400 175 225 Direct Materials (2) 100% $32,000 ' ( Conversion Total Costs Costs (3) (4) 5 (2) 1 (3) 60% $18,600 $50,600 www.downloadslide.com Case 2: ProCess Costing with Zero Beginning and some ending work-in-ProCess inventory The 225 partially assembled units as of February 28, 2017, are fully processed for direct materials because all direct materials in the assembly department are added at the beginning of the assembly process. Conversion costs, however, are added evenly during assembly. An assembly department supervisor estimates that the partially assembled units are, on average, 60% complete with respect to conversion costs. The accuracy of the completion estimate of conversion costs depends on the care, skill, and experience of the estimator and the nature of the conversion process. Estimating the degree of completion is usually easier for direct materials costs than for conversion costs because the quantity of direct materials needed for a completed unit and the quantity of direct materials in a partially completed unit can be measured more accurately. In contrast, the conversion sequence usually consists of a number of operations, each for a specified period of time, at various steps in the production process.2 The degree of completion for conversion costs depends on the proportion of the total conversion costs needed to complete one unit (or a batch of production) that has already been incurred on the units still in process. Department supervisors and line managers are most familiar with the conversion process, so they most often estimate completion rates for conversion costs. However, in some industries, such as semiconductor manufacturing, no exact estimate is possible because manufacturing occurs inside sealed environments that can be opened only when the process is complete. In other settings, such as the textile industry, vast quantities of unfinished products such as shirts and pants make the task of estimation too costly. In these cases, to calculate the conversion costs, managers assume that all work in process in a department is complete to some preset degree (for example, one-third, one-half, or two-thirds). Because some units are fully assembled and some are only partially assembled, a common metric is needed to compare the work that’s been done on them and, more importantly, obtain a total measure of the work done. The concept we will use in this regard is that of equivalent units. We will explain this concept in greater detail next as part of the set of five steps required to calculate (1) the cost of fully assembled units in February 2017 and (2) the cost of partially assembled units still in process at the end of that month, for Pacific Electronics. The five steps of process costing are as follows: Step 1: Summarize the flow of physical units of output. Step 2: Compute output in terms of equivalent units. Step 3: Summarize the total costs to account for. Step 4: Compute the cost per equivalent unit. Step 5: Assign the total costs to the units completed and to the units in ending work-in-process inventory. Summarizing the Physical Units and Equivalent Units (Steps 1 and 2) In Step 1, managers track the physical units of output. Recall that physical units are the number of output units, whether complete or incomplete. The physical-units column of Exhibit 17-1 tracks where the physical units came from (400 units started) and where they went (175 units completed and transferred out and 225 units in ending inventory). Remember that when there is no beginning inventory, the number of units started must equal the sum of units transferred out and ending inventory. Because not all 400 physical units are fully completed, in Step 2, managers compute the output in equivalent units, not in physical units. Equivalent units are a derived measure of output calculated by (1) taking the quantity of each input (factor of production) in units 2 For example, consider the conventional tanning process for converting hide to leather. Obtaining 250–300 kg of leather requires putting one metric ton of raw hide through as many as 15 steps: from soaking, liming, and pickling to tanning, dyeing, and fatliquoring, the step in which oils are introduced into the skin before the leather is dried. 679 www.downloadslide.com 680 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing exHibit 17-1 Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units for the Assembly Department for February 2017 $ % (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning Started during current period To account for Completed and transferred out during current period Work in process, ending a (225 3 100%; 225 3 60%) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done in current period a Physical Units 0 400 400 175 225 400 & ' (Step 2) Equivalent Units Direct Conversion Materials Costs 175 175 225 135 400 310 Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 60%. completed and in incomplete units of work in process and (2) converting the quantity of input into the amount of completed output units that could be produced with that quantity of input. To see what is meant by equivalent units, suppose that during a month, 50 physical units were started but not completed. Managers estimate that the 50 units in ending inventory are 70% complete for conversion costs. Now, suppose all the conversion costs represented in these units were used to make fully completed units instead. How many completed units would that have resulted in? The answer is 35 units. Why? Because the conversion costs incurred to produce 50 units that are each 70% complete could have instead generated 35 (0.70 * 50) units that are 100% complete. The 35 units are referred to as equivalent units of output. That is, in terms of the work done on them, the 50 partially completed units are considered equivalent to 35 completed units. Note that equivalent units are calculated separately for each input (such as direct materials and conversion costs). Moreover, every completed unit, by definition, is composed of one equivalent unit of each input required to make it. This chapter focuses on equivalent-unit calculations in manufacturing settings, but the calculations can be used in nonmanufacturing settings as well. For example, universities convert their part-time student enrollments into “full-time student equivalents” to get a better measure of faculty–student ratios over time. Without this adjustment, an increase in part-time students would lead to a lower faculty– student ratio. This would erroneously suggest a decline in the quality of instruction when, in fact, part-time students take fewer academic courses and do not need the same number of instructors as full-time students do. When calculating the equivalent units in Step 2, focus on quantities. Disregard dollar amounts until after the equivalent units are computed. In the Pacific Electronics example, all 400 physical units—the 175 fully assembled units and the 225 partially assembled units—are 100% complete with respect to direct materials because all direct materials are added in the assembly department at the start of the process. Therefore, Exhibit 17-1 shows that the output is 400 equivalent units for direct materials: 175 equivalent units for the 175 physical units assembled and transferred out and 225 equivalent units for the 225 physical units in ending work-in-process inventory. The 175 fully assembled units have also incurred all of their conversion costs. The 225 partially assembled units in ending work in process are 60% complete (on average). Therefore, their conversion costs are equivalent to the conversion costs incurred by 135 fully assembled units (225 * 60% = 135). Hence, Exhibit 17-1 shows that the output is a total of 310 equivalent units for the conversion costs: 175 equivalent units for the 175 physical units assembled and transferred out and 135 equivalent units for the 225 physical units in ending work-in-process inventory. www.downloadslide.com Case 2: ProCess Costing with Zero Beginning and some ending work-in-ProCess inventory 681 Calculating Product Costs (Steps 3, 4, and 5) Exhibit 17-2 shows Steps 3, 4, and 5. Together, they are called the production cost worksheet. In Step 3, managers summarize the total costs to account for. Because the beginning balance of work-in-process inventory is zero on February 1, the total costs to account for (that is, the total charges or debits to the Work in Process—Assembly account) consist only of costs added during February: $32,000 in direct materials and $18,600 in conversion costs, for a total of $50,600. In Step 4, managers calculate the cost per equivalent unit separately for the direct materials costs and conversion costs. This is done by dividing the direct material costs and conversion costs added during February by their related quantities of equivalent units of work done in February (as calculated in Exhibit 17-1). To see why it is important to understand equivalent units in unit-cost calculations, compare the conversion costs for January and February 2017. The $18,600 in total conversion costs for the 400 units worked on during February are lower than the $24,000 in total conversion costs for the 400 units worked on in January. However, the conversion costs to fully assemble a unit are the same: $60 per unit in both January and February. Total conversion costs are lower in February because fewer equivalent units of conversion-costs work were completed in that month than in January (310 in February versus 400 in January). Note that using physical units instead of equivalent units would have resulted in a conversion cost per unit of just $46.50 ($18,600 , 400 units) for February, which is down from $60 in January. This incorrect costing would lead the firm’s managers to believe that the assembly department achieved efficiencies that lowered the conversion costs of the SG-40 when in fact the costs had stayed the same. Once the cost per equivalent unit is calculated for both the direct materials and conversion costs, managers can move to Step 5: assigning the total direct materials and conversion costs to the units completed and transferred out and to the units still in process at the end of February 2017. As Exhibit 17-2 shows, this is done by multiplying the equivalent output units for each input by the cost per equivalent unit. For example, the total costs (direct materials exHibit 17-2 Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory for the Assembly Department for February 2017 $ % (Step 3) Costs added during February Total costs to account for (Step 4) Costs added in current period Divide by equivalent units of work done in current period (Exhibit 17-1) Cost per equivalent unit (Step 5) Assignment of costs: & ' Total Production Costs $50,600 $50,600 Direct Materials $32,000 $32,000 ( ) Conversion Costs 1 $18,600 $18,600 1 $32,000 4 400 $ 80 $18,600 4 310 $ 60 Completed and transferred out (175 units) Work in process, ending (225 units) Total costs accounted for a Equivalent units completed and transferred out from Exhibit 17-1, step 2. b Equivalent units in ending work in process from Exhibit 17-1, step 2. $24,500 26,100 $50,600 (175a 3 $80) b (225 3 $80) $32,000 a 1 (175 3 $60) 1 (135b 3 $60) 1 $18,600 www.downloadslide.com 682 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing and conversion costs assigned to the 225 physical units in ending work-in-process inventory) are as follows: Direct material costs of 225 equivalent units (calculated in Step 2) * $80 cost per equivalent unit of direct materials (calculated in Step 4) Conversion costs of 135 equivalent units (calculated in Step 2) * $60 cost per equivalent unit of conversion costs (calculated in Step 4) Total cost of ending work-in-process inventory $18,000 8,100 $26,100 Note that the total costs to account for in Step 3 ($50,600) equal the total costs accounted for in Step 5. Journal Entries Journal entries in process-costing systems are similar to the entries made in job-costing systems with respect to direct materials and conversion costs. The main difference is that, when process costing is used, there is one Work in Process account for each process. In our example, there are accounts for (1) Work in Process—Assembly and (2) Work in Process—Testing. Pacific Electronics purchases direct materials as needed. These materials are delivered directly to the assembly department. Using the amounts from Exhibit 17-2, the summary journal entries for February are as follows: 1. 2. 3. Work in Process—Assembly Accounts Payable Control To record the direct materials purchased and used in production during February. Work in Process—Assembly Various accounts such as Wages Payable Control and Accumulated Depreciation To record the conversion costs for February; examples include energy, manufacturing supplies, all manufacturing labor, and plant depreciation. Work in Process—Testing Work in Process—Assembly To record the cost of goods completed and transferred from assembly to testing during February. 32,000 32,000 18,600 18,600 24,500 24,500 Exhibit 17-3 shows a general framework for the flow of costs through T-accounts. Notice how entry 3 for $24,500 follows the physical transfer of goods from the assembly to the Flow of Costs in a Process-Costing System for the Assembly Department for February 2017 exHibit 17-3 Accounts Payable Control 32,000 Various Accounts 18,600 Work in Process—Assembly 32,000 18,600 24,500 Work in Process—Testing Bal. xx 24,500 Transferred Out to Finished Goods xx Bal. 26,100 Finished Goods xx Cost of Goods Sold xx Cost of Goods Sold xx www.downloadslide.com Case 2: ProCess Costing with Zero Beginning and some ending work-in-ProCess inventory 683 testing department. The T-account Work in Process—Assembly shows February 2017’s ending balance of $26,100, which is the beginning balance of Work in Process—Assembly in March 2017. It is important to ensure that all costs have been accounted for and that the ending inventory of the current month is the beginning inventory of the following month. Earlier, we discussed the importance of accurately estimating the completion percentages for conversion costs. We can now calculate the effect of incorrect estimates of the degree of completion of units in ending work in process. Suppose, for example, that Pacific Electronics’ managers overestimate the degree of completion for conversion costs at 80% instead of 60%. The computations would change as follows: ■ ■ ■ Exhibit 17-1, Step 2 Equivalent units of conversion costs in ending Work in Process—Assembly = 80% * 225 = 180 Equivalent units of conversion costs for work done in the current period = 175 + 180 = 355 Exhibit 17-2, Step 4 Cost per equivalent unit of conversion costs = $18,600 , 355 = $52.39 Cost per equivalent unit of direct materials is unchanged, $80 Exhibit 17-2, Step 5 Cost of 175 units of goods completed and transferred out = 175 * $80 + 175 * $52.39 = $23,168.25 This amount is lower than the $24,500 of costs assigned to goods completed and transferred out calculated in Exhibit 17-2. Overestimating the degree of completion decreases the costs assigned to goods transferred out and eventually to cost of goods sold and increases operating income. Managers must ensure that department supervisors avoid introducing personal biases into estimates of degrees of completion. To show better performance, for example, a department supervisor might report a higher degree of completion resulting in overstated operating income. If performance for the period is very good, the department supervisor may be tempted to report a lower degree of completion, reducing income in the current period. This has the effect of reducing the costs carried in ending inventory and the costs carried to the following period in beginning inventory. In other words, estimates of degree of completion can help to smooth earnings from one period to the next. To guard against the possibility of bias, managers should ask supervisors specific questions about the process they followed to prepare estimates. Top management should always emphasize obtaining the correct answer, regardless of how it affects reported performance. This emphasis drives ethical actions throughout the organization. Big Band Corporation produces a semiconductor chip used in communications. The direct materials are added at the start of the production process, while conversion 17-1 costs are added uniformly throughout the production process. Big Band had no inventory at the start of June. During the month, it incurred direct materials costs of $935,750 and conversion costs of $4,554,000. Big Band started 475,000 chips and completed 425,000 of them in June. Ending inventory was 50% complete as to conversion costs. Compute (a) the equivalent units of work done in June, and (b) the total manufacturing cost per chip. Allocate the total costs between the completed chips and those in ending inventory. DecisiOn Point What are the five steps in a process-costing system, and how are equivalent units calculated? try it! www.downloadslide.com 684 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing Case 3: Process Costing with Some Beginning and Some Ending Work-in-Process Inventory At the beginning of March 2017, Pacific Electronics had 225 partially assembled SG-40 units in the assembly department. It started production of another 275 units in March. The data for the assembly department for March are as follows: $ Work in process, beginning inventory (March 1) % Physical Units (SG-40s) (1) 225 & Direct Materials (2) a $18,000 100% Degree of completion of beginning work in process 275 Started during March 400 Completed and transferred out during March 100 Work in process, ending inventory (March 31) Degree of completion of ending work in process 100% $19,800 Total costs added during March a Work in process, beginning inventory (equals work in process, ending inventory for February) Direct materials: 225 physical units 3 100% completed 3 $80 per unit 5 $18,000 Conversion costs: 225 physical units 3 60% completed 3 $60 per unit 5 $8,100 Learning Objective 4 Use the weighted-average method . . . assign costs based on total costs and equivalent units completed to date and the first-in, first-out (FIFO) method . . . assign costs based on costs and equivalent units of work done in the current period of process costing ' Conversion Costs (3) a $8,100 60% 50% $16,380 ( Total Costs (4) 5 (2) 1 (3) $26,100 $36,180 Pacific Electronics has incomplete units in both beginning work-in-process inventory and ending work-in-process inventory for March 2017. We can still use the five steps described earlier to calculate (1) the cost of units completed and transferred out and (2) the cost of ending work-in-process inventory. To assign costs to each of these categories, however, we first need to choose an inventory-valuation method. We next describe the five-step approach for two key methods—the weighted-average method and the first-in, first-out method. These different valuation methods produce different costs for the units completed and for the ending work-in-process inventory when the unit cost of inputs changes from one period to the next. Weighted-Average Method The weighted-average process-costing method calculates the cost per equivalent unit of all work done to date (regardless of the accounting period in which it was done) and assigns this cost to equivalent units completed and transferred out of the process and to equivalent units in ending work-in-process inventory. The weighted-average cost is the total of all costs entering the Work in Process account (whether the costs are from beginning work in process or from work started during the current period) divided by total equivalent units of work done to date. We now describe the weighted-average method using the five-step procedure introduced on page 679. Step 1: Summarize the Flow of Physical Units of Output. The physical-units column in Exhibit 17-4 shows where the units came from—225 units from beginning inventory and 275 units started during the current period—and where the units went—400 units completed and transferred out and 100 units in ending inventory. Step 2: Compute the Output in Terms of Equivalent Units. We use the relationship shown in the following equation: Equivalent units Equivalent units Equivalent units Equivalent units in beginning work + of work done in = completed and transferred + in ending work in process current period out in current period in process www.downloadslide.com Case 3: ProCess Costing with some Beginning and some ending work-in-ProCess inventory 685 exHibit 17-4 $ % (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given, p. 684) Started during current period (given, p. 684) To account for Completed and transferred out during current period Work in process, ending a (given, p. 684) (1 0 0 3 1 0 0 % ; 1 0 0 3 5 0 % ) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done to date a Physical Units 225 275 500 400 100 500 & ' (Step 2) Equivalent Units Direct Conversion Materials Costs 400 400 100 50 500 450 Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. Although we are interested in calculating the left side of the preceding equation, it is easier to calculate this sum using the equation’s right side: (1) the equivalent units completed and transferred out in the current period plus (2) the equivalent units in ending work in process. Note that the stage of completion of the current-period beginning work in process is not used in this computation. The equivalent-units columns in Exhibit 17-4 show the equivalent units of work done to date: 500 equivalent units of direct materials and 450 equivalent units of conversion costs. All completed and transferred-out units are 100% complete with regard to both their direct materials and conversion costs. Partially completed units in ending work in process are 100% complete with regard to their direct materials costs (because the direct materials are introduced at the beginning of the process) and 50% complete with regard to their conversion costs, based on estimates from the assembly department manager. Step 3: Summarize the Total Costs to Account For. Exhibit 17-5 presents Step 3. The total costs to account for in March 2017 are described in the example data on page 684: Beginning work in process (direct materials, $18,000 + conversion costs, $8,100) Costs added during March (direct materials, $19,800 + conversion costs, $16,380) Total costs to account for in March $26,100 36,180 $62,280 Step 4: Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit. Exhibit 17-5, Step 4, shows how the weighted-average cost per equivalent unit for direct materials and conversion costs is computed. The weighted-average cost per equivalent unit is obtained by dividing the sum of the costs for beginning work in process plus the costs for work done in the current period by the total equivalent units of work done to date. For example, we calculate the weighted-average conversion cost per equivalent unit in Exhibit 17-5 as follows: Total conversion costs (beginning work in process, $8,100 + work done in current period, $16,380) Divided by the total equivalent units of work done to date (equivalent units of conversion costs in beginning work in process and in work done in current period) Weighted-average cost per equivalent unit $24,480 450 $ 54.40 Step 5: Assign Costs to the Units Completed and to Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory. Step 5 in Exhibit 17-5 takes the equivalent units completed and transferred out and the equivalent units in ending work in process (calculated in Exhibit 17-4, Step 2) and assigns dollar Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units Using the Weighted-Average Method for the Assembly Department for March 2017 www.downloadslide.com 686 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing exHibit 17-5 $ Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory Using the Weighted-Average Method for the Assembly Department for March 2017 % (Step 3) Work in process, beginning (given, p. 684) Costs added in current period (given, p. 684) Total costs to account for (Step 4) Costs incurred to date Divide by equivalent units of work done to date (Exhibit 17-4) Cost per equivalent unit of work done to date (Step 5) Assignment of costs: Completed and transferred out (400 units) Work in process, ending (100 units) Total costs accounted for & ' Total Production Costs Direct Materials $26,100 36,180 $62,280 $18,000 19,800 $37,800 $37,800 4 500 $ 75.60 $52,000 10,280 $62,280 a ( ) Conversion Costs 1 1 1 $ 8,100 16,380 $24,480 $24,480 4 450 $ 54.40 a (400 3 $75.60) 1 (400 3 $54.40) b b (100 3 $75.60) 1 (50 3 $54.40) $24,480 1 $37,800 a Equivalent units completed and transferred out from Exhibit 17-4, Step 2. b Equivalent units in ending work in process from Exhibit 17-4, Step 2. amounts to them using the weighted-average cost per equivalent unit for the direct materials and conversion costs calculated in Step 4. For example, the total costs of the 100 physical units in ending work in process are as follows: Direct materials: 100 equivalent units * weighted@average cost per equivalent unit of $75.60 Conversion costs: 50 equivalent units * weighted@average cost per equivalent unit of $54.40 Total costs of ending work in process $ 7,560 2,720 $10,280 The following table summarizes total costs to account for ($62,280) and how they are accounted for in Exhibit 17-5. The arrows indicate that the costs of units completed and transferred out and units in ending work in process are calculated using weighted-average total costs obtained after merging costs of beginning work in process and costs added in the current period. Costs to Account For Beginning work in process Costs added in current period Total costs to account for $26,100 36,180 $62,280 Costs Accounted for Calculated on a Weighted-Average Basis Completed and transferred out $52,000 Ending work in process 10,280 Total costs accounted for $62,280 Before proceeding, review Exhibits 17-4 and 17-5 to check your understanding of the weightedaverage method. Note: Exhibit 17-4 deals with only physical and equivalent units, not costs. Exhibit 17-5 shows the cost amounts. www.downloadslide.com Case 3: ProCess Costing with some Beginning and some ending work-in-ProCess inventory 687 Using amounts from Exhibit 17-5, the summary journal entries under the weightedaverage method for March 2017 are as follows: 1. Work in Process—Assembly Accounts Payable Control To record the direct materials purchased and used in production during March. 2. Work in Process—Assembly Various accounts such as Wages Payable Control and Accumulated Depreciation To record the conversion costs for March; examples include energy, manufacturing supplies, all manufacturing labor, and plant depreciation. 3. Work in Process—Testing Work in Process—Assembly To record the cost of goods completed and transferred from assembly to testing during March. 19,800 19,800 16,380 16,380 52,000 52,000 The T-account Work in Process—Assembly, under the weighted-average method, is as follows: Beginning inventory, March 1 ① Direct materials ② Conversion costs Work in Process—Assembly 26,100 ③ Completed and transferred 19,800 out to Work in Process— 16,380 Testing Ending inventory, March 31 52,000 10,280 The Stanton Processing Company had work in process at the beginning and end of March 2017 in its Painting Department as follows: March 1 March 31 (3,000 units) (2,000 units) 17-2 Percentage of Completion Direct Materials Conversion Costs 40% 10% 80% 40% The company completed 30,000 units during March. Manufacturing costs incurred during March were direct materials costs of $ 176,320 and conversion costs of $ 312,625. Inventory at March 1 was carried at a cost of $ 16,155 (direct materials, $5,380 and conversion costs, $10,775). Assuming Stanton uses weighted-average costing, determine the equivalent units of work done in March, and calculate the cost of units completed and the cost of units in ending inventory. First-In, First-Out Method The first-in, first-out (FIFO) process-costing method (1) assigns the cost of the previous accounting period’s equivalent units in beginning work-in-process inventory to the first units completed and transferred out of the process and (2) assigns the cost of equivalent units worked on during the current period first to complete the beginning inventory, next to start and complete new units, and finally to units in ending work-in-process inventory. The FIFO method assumes that the earliest equivalent units in work in process are completed first. A distinctive feature of the FIFO process-costing method is that work done on the beginning inventory before the current period is kept separate from work done in the current period. The costs incurred and units produced in the current period are used to calculate the cost per equivalent unit of work done in the current period. In contrast, the equivalent-unit try it! www.downloadslide.com 688 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing and cost-per-equivalent-unit calculations under the weighted-average method merge the units and costs in beginning inventory with the units and costs of work done in the current period. We now describe the FIFO method using the five-step procedure introduced on page 679. Step 1: Summarize the Flow of Physical Units of Output. Exhibit 17-6, Step 1, traces the flow of the physical units of production and explains how they are calculated under the FIFO method. ■ ■ ■ ■ The first physical units assumed to be completed and transferred out during the period are 225 units from beginning work-in-process inventory. The March data on page 684 indicate that 400 physical units were completed during March. The FIFO method assumes that of these 400 units, 175 units (400 units - 225 units from beginning work-in-process inventory) must have been started and completed during March. The ending work-in-process inventory consists of 100 physical units—the 275 physical units started minus the 175 units that were started and completed. The physical units “to account for” equal the physical units “accounted for” (500 units). Step 2: Compute the Output in Terms of Equivalent Units. Exhibit 17-6 also presents the computations for Step 2 under the FIFO method. The equivalent-unit calculations for each cost category focus on equivalent units of work done in the current period (March) only. Under the FIFO method, the equivalent units of work done in March on the beginning work-in-process inventory equal 225 physical units times the percentage of work remaining to be done in March to complete these units: 0% for direct materials, because the beginning work in process is 100% complete for direct materials, and 40% for conversion costs, because the beginning work in process is 60% complete for conversion costs. The results are 0 (0% * 225) equivalent units of work for direct materials and 90 (40% * 225) equivalent units of work for conversion costs. The equivalent units of work done on the 175 physical units started and completed equals 175 units times 100% for both direct materials and conversion costs because all work on these units is done in the current period. exHibit 17-6 Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units Using the FIFO Method for the Assembly Department for March 2017 $ % (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given, p. 684) Started during current period (given, p. 684) To account for Completed and transferred out during current period: From beginning work in process a [225 3 (100% ] 100%); 225 3 (100% ] 60%)] Started and completed (1 7 5 3 1 0 0 % ; 1 7 5 3 1 0 0 % ) Work in process, ending c (given, p. 684) (1 0 0 3 1 0 0 % ; 1 0 0 3 5 0 % ) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done in current period a Physical Units 225 275 500 225 175b 100 500 & 0 90 175 175 100 50 275 315 Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 60%. 400 physical units completed and transferred out minus 225 physical units completed and transferred out from beginning work-in-process inventory. c Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. b ' (Step 2) Equivalent Units Direct Conversion Materials Costs (work done before current period) www.downloadslide.com Case 3: ProCess Costing with some Beginning and some ending work-in-ProCess inventory The equivalent units of work done on the 100 units of ending work in process equal 100 physical units times 100% for direct materials (because all direct materials for these units are added in the current period) and 50% for conversion costs (because 50% of the conversioncosts work on these units is done in the current period). Step 3: Summarize the Total Costs to Account For. Exhibit 17-7 presents Step 3 and summarizes the $62,280 in total costs to account for in March 2017 (the costs of the beginning work in process, $26,100, and the costs added in the current period, $36,180). Step 4: Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit. Exhibit 17-7 shows the Step 4 computation of the cost per equivalent unit of work done in the current period only for the direct materials and conversion costs. For example, the conversion cost per equivalent unit of $52 is obtained by dividing the current-period conversion costs of $16,380 by the current-period conversion-costs equivalent units of 315. Step 5: Assign Costs to the Units Completed and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory. Exhibit 17-7 shows the assignment of costs under the FIFO method. The costs of work done in the current period are assigned (1) first to the additional work done to complete the beginning work-in-process inventory, then (2) to work done on units started and completed during the current period, and finally (3) to ending work-in-process inventory. Step 5 takes each quantity of equivalent units calculated in Exhibit 17-6, Step 2, and assigns dollar amounts to them (using the cost-per-equivalent-unit calculations in Step 4). The goal is to use the cost of work done in the current period to determine the total costs of all units completed from exHibit 17-7 Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory Using the FIFO Method for the Assembly Department for March 2017 $ % (Step 3) Work in process, beginning (given, p. 684) Costs added in current period (given, p. 684) Total costs to account for & ' Total Production Costs $26,100 36,180 $62,280 Direct Materials $18,000 19,800 $37,800 ( ) 1 Conversion Costs $ 8,100 16,380 $24,480 1 1 $19,800 4 275 $ 72 (Step 4) Costs added in current period Divide by equivalent units of work done in current period (Exhibit 17-6) Cost per equivalent unit of work done in current period $16,380 4 315 $ 52 (Step 5) Assignment of costs: Completed and transferred out (400 units): Work in process, beginning (225 units) Costs added to beginning work in process in current period Total from beginning inventory Started and completed (175 units) Total costs of units completed and transferred out Work in process, ending (100 units) Total costs accounted for $26,100 $18,000 a 1 $8,100 a 4,680 30,780 (0 3 $72) 1 (90 3 $52) 21,700 52,480 (175b 3 $72) 1 (175b 3 $52) 9,800 $62,280 (100c 3 $72) $37,800 1 1 (50c 3 $52) $24,480 a Equivalent units used to complete beginning work in process from Exhibit 17-6, Step 2. b Equivalent units started and completed from Exhibit 17-6, Step 2. c Equivalent units in ending work in process from Exhibit 17-6, Step 2. 689 www.downloadslide.com 690 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing beginning inventory and from work started and completed in the current period and the costs of ending work-in-process inventory. Of the 400 completed units, 225 units are from beginning inventory and 175 units are started and completed during March. The FIFO method starts by assigning the costs of the beginning work-in-process inventory of $26,100 to the first units completed and transferred out. As we saw in Step 2, an additional 90 equivalent units of conversion costs are needed to complete these units in the current period. The current-period conversion cost per equivalent unit is $52, so $4,680 (90 equivalent units * $52 per equivalent unit) of additional costs are incurred to complete the beginning inventory. The total production costs for units in beginning inventory are therefore $26,100 + $4,680 = $30,780. The 175 units started and completed in the current period consist of 175 equivalent units of direct materials and 175 equivalent units of conversion costs. These units are costed at the cost per equivalent unit in the current period (direct materials, $72, and conversion costs, $52) for a total production cost of $21,700 [175 * ($72 + $52)]. Under FIFO, the ending work-in-process inventory comes from units that were started but not fully completed during the current period. The total costs of the 100 partially assembled physical units in ending work in process are as follows: Direct materials: 100 equivalent units * $72 cost per equivalent unit in March Conversion costs: 50 equivalent units * $52 cost per equivalent unit in March Total cost of work in process on March 31 $7,200 2,600 $9,800 The following table summarizes the total costs to account for and the costs accounted for under FIFO, which are $62,280 in Exhibit 17-7. Notice how the FIFO method keeps separate the layers of the beginning work-in-process costs and the costs added in the current period. The arrows indicate where the costs in each layer go—that is, to units completed and transferred out or to ending work in process. Be sure to include the costs of the beginning work-in-process inventory ($26,100) when calculating the costs of units completed. Costs Accounted for Calculated on a FIFO Basis Completed and transferred out: Costs to Account for Beginning work in process Costs added in current period $26,100 36,180 Beginning work in process Used to complete beginning work in process Started and completed Completed and transferred out Total costs to account for $62,280 Ending work in process Total costs accounted for $26,100 4,680 21,700 52,480 9,800 $62,280 Before proceeding, review Exhibits 17-6 and 17-7 to check your understanding of the FIFO method. Note: Exhibit 17-6 deals with only physical and equivalent units, not costs. Exhibit 17-7 shows the cost amounts. The journal entries under the FIFO method are identical to the journal entries under the weighted-average method except for one difference. The entry to record the cost of goods completed and transferred out would be $52,480 under the FIFO method instead of $52,000 under the weighted-average method. Keep in mind that FIFO is applied within each department to compile the cost of units transferred out. As a practical matter, however, units transferred in during a given period usually are carried at a single average unit cost. For example, in the preceding example, the assembly department uses FIFO to distinguish between monthly batches of production. The resulting average cost of each SG-40 unit transferred out of the assembly department is $52,480 , 400 units = $131.20. The testing department, however, costs these units (which consist of costs incurred in both February and March) at one average unit cost ($131.20 in this example). If this averaging were not done, the attempt to track costs on a pure FIFO basis throughout a series of processes would be cumbersome. As a result, the FIFO method should really be called a modified or department FIFO method. www.downloadslide.com Case 3: ProCess Costing with some Beginning and some ending work-in-ProCess inventory Consider Stanton Processing Company again. With the same information for 2017 as provided in Try It! 17-2, redo the problem assuming Stanton uses FIFO costing instead. 17-3 Comparing the Weighted-Average and FIFO Methods Consider the summary of the costs assigned to units completed and to units still in process under the weighted-average and FIFO process-costing methods in our example for March 2017: Cost of units completed and transferred out Work in process, ending Total costs accounted for Weighted Average (from Exhibit 17-5) $52,000 10,280 $62,280 FIFO (from Exhibit 17-7) $52,480 9,800 $62,280 Difference + $480 - $480 The weighted-average ending inventory is higher than the FIFO ending inventory by $480, or 4.9% ($480 , $9,800 = 0.049, or 4.9%). This would be a significant difference when aggregated over the many thousands of products Pacific Electronics makes. When completed units are sold, the weighted-average method in our example leads to a lower cost of goods sold and, therefore, higher operating income than the FIFO method does. To see why, recall the data on page 684. For the beginning work-in-process inventory, the direct materials cost per equivalent unit is $80 and the conversion cost per equivalent unit is $60. These costs are greater, respectively, than the $72 direct materials cost and the $52 conversion cost per equivalent unit of work done during the current period. The current-period costs could be lower due to a decline in the prices of direct materials and conversion-cost inputs or as a result of Pacific Electronics becoming more efficient in its processes by using smaller quantities of inputs per unit of output or both. FIFO assumes that (1) all the higher-cost units from the previous period in beginning work in process are the first to be completed and transferred out of the process and (2) the ending work in process consists of only the lower-cost current-period units. The weightedaverage method, however, smooths out the cost per equivalent unit by assuming that (1) more of the lower-cost units are completed and transferred out and (2) some of the higher-cost units are placed in ending work in process. The decline in the current-period cost per equivalent unit results in a lower cost of units completed and transferred out and a higher ending workin-process inventory under the weighted-average method relative to FIFO. Managers use information from process-costing systems to make pricing and productmix decisions and understand how well a firm’s processes are performing. FIFO provides managers with information about changes in the costs per unit from one period to the next. Managers can use this data to adjust selling prices based on current conditions (for example, based on the $72 direct materials cost and $52 conversion cost in March). Managers can also more easily evaluate the firm’s cost performance relative to either a budget or the previous period (for example, both unit direct materials and conversion costs have declined relative to the prior period). By focusing on the work done and the costs of work done during the current period, the FIFO method provides valuable information for these planning and control purposes. The weighted-average method merges unit costs from different accounting periods, obscuring period-to-period comparisons. For example, the weighted-average method would lead managers at Pacific Electronics to make decisions based on the $75.60 direct materials and $54.40 conversion costs, rather than the costs of $72 and $52 prevailing in the current period. However, costs are relatively easy to compute using the weighted-average method, and it results in a more-representative average unit cost when input prices fluctuate markedly from month to month. The cost of units completed and, hence, a firm’s operating income differ materially between the weighted-average and FIFO methods when (1) the direct materials or conversion cost per equivalent unit varies significantly from period to period and (2) the physical-inventory 691 try it! www.downloadslide.com 692 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing DecisiOn Point What are the weightedaverage and first-in, first-out (FIFO) methods of process costing? Under what conditions will they yield different levels of operating income? levels of the work in process are large relative to the total number of units transferred out of the process. As changes in unit costs and inventory levels across periods decrease, the difference in the costs of units completed under the weighted-average and FIFO methods also decreases.3 When the cost of units completed under the weighted-average and FIFO methods differs substantially, which method should a manager choose? In a period of falling prices, as in the Pacific Electronics case, the higher cost of goods sold under the FIFO method will lead to lower operating income and lower tax payments, saving the company cash and increasing the company’s value. FIFO is the preferred choice, but managers may not make this choice. If the manager’s compensation, for instance, is based on operating income, the manager may prefer the weighted-average method, which increases operating income even though it results in higher tax payments. Top managers must carefully design compensation plans to encourage managers to take actions that increase a company’s value. For example, the compensation plan might reward after-tax cash flow metrics, in addition to operating income metrics, to align decision making and performance evaluation. Occasionally, choosing a process-costing method can be more difficult. Suppose, for example, that by using FIFO a company would violate its debt covenants (agreements between a company and its creditors that the company will maintain certain financial ratios) resulting in its loans coming due. In this case, a manager may prefer the weighted-average method even though it results in higher taxes because the company does not have the liquidity to repay its loans. In a period of rising prices, the weighted-average method will decrease taxes because cost of goods sold will be higher and operating income lower. Readers familiar with the last-in, first-out (LIFO) method (not presented in this chapter) will appreciate that with rising prices, the LIFO method reduces operating income and taxes even more than the weighted-average method. Finally, how is activity-based costing related to process costing? Like activity-based processing, each process—assembly, testing, and so on—can be considered a different (production) activity. However, no additional activities need to be identified within each process to use process costing. That’s because products are homogeneous and use the resources of each process in a uniform way. The bottom line is that activity-based costing has less applicability in process-costing environments, especially when compared to the significant role it plays in job costing. The appendix illustrates the use of the standard costing method for the assembly department. Transferred-In Costs in Process Costing Learning Objective 5 Apply process-costing methods to situations with transferred-in costs . . . using weighted-average and FIFO methods Many process-costing systems have two or more departments or processes in the production cycle. As units move from department to department, the related costs are also transferred by monthly journal entries. Transferred-in costs (also called previous-department costs) are costs incurred in previous departments that are carried forward as the product’s cost when it moves to a subsequent process in the production cycle. We now extend our Pacific Electronics example to the testing department. As the assembly process is completed, the assembly department of Pacific Electronics immediately transfers SG-40 units to the testing department. Conversion costs are added evenly during the testing department’s process. At the end of the testing process, the units receive additional direct materials, including crating and other packing materials to prepare them for shipment. As units are completed in testing, they are immediately transferred to Finished Goods. The testing department costs consist of transferred-in costs, as well as direct materials and conversion costs added during testing. 3 For example, suppose the beginning work-in-process inventory for March was 125 physical units (instead of 225), and suppose the costs per equivalent unit of work done in the current period (March) were direct materials, $75, and conversion costs, $55. Assume that all other data for March are the same as in our example. In this case, the cost of units completed and transferred out would be $52,833 under the weighted-average method and $53,000 under the FIFO method. The work-in-process ending inventory would be $10,417 under the weighted-average method and $10,250 under the FIFO method (calculations not shown). These differences are much smaller than in the chapter example. The weighted-average ending inventory is higher than the FIFO ending inventory by only $167 ($10,417 - $10,250), or 1.6% ($167 , $10,250 = 0.016), compared with 4.9% higher in the chapter example. www.downloadslide.com transferred-in Costs in ProCess Costing The following diagram represents these facts: Conversion costs added evenly during process Assembly Department Transfer Finished Goods Testing Department Direct materials added at end of process The data for the testing department for March 2017 are as follows: $ Work in process, beginning inventory (March 1) Degree of completion, beginning work in process Transferred-in during March Completed and transferred out during March Work in process, ending inventory (March 31) Degree of completion, ending work in process Total costs added during March: Direct materials and conversion costs Transferred-in (Weighted-average from Exhibit 17-5) a Transferred-in (FIFO from Exhibit 17-7)a % & Physical Units Transferred-In (SG-40s) Costs 240 $33,600 100% 400 440 200 100% $52,000 $52,480 ' ( Direct Materials $ 0 0% Conversion Costs $18,000 62.5% 0% 80% $13,200 $48,600 a The transferred-in costs during March are different under the weighted-average method (Exhibit 17-5) and the FIFO method (Exhibit 17-7). In our example, beginning work-in-process inventory, $51,600 ($33,600 1 $0 1 $18,000) is the same under both the weighted-average and FIFO inventory methods because we assume costs per equivalent unit to be the same in both January and February. If costs per equivalent unit had been different in the two months, work-in-process inventory at the end of February (beginning of March) would be costed differently under the weighted-average and FIFO methods. The basic approach to process costing with transferred-in costs, however, would still be the same as what we describe in this section. Transferred-in costs are treated as if they are a separate type of direct materials added at the beginning of the process. That is, the transferred-in costs are always 100% complete at the beginning of the process in the new department. When successive departments are involved, the transferred units from one department become all or a part of the direct materials of the next department; however, they are called transferred-in costs, not direct materials costs. Transferred-In Costs and the Weighted-Average Method To examine the weighted-average process-costing method with transferred-in costs, we use the five-step procedure described earlier (page 679) to assign the costs of the testing department to units completed and transferred out and to the units in ending work in process. Exhibit 17-8 shows Steps 1 and 2. The computations are similar to the calculations of equivalent units under the weighted-average method for the assembly department in Exhibit 17-4. The one difference here is that we have transferred-in costs as an additional input. All units, whether completed and transferred out during the period or in ending work in process, are always fully complete with respect to transferred-in costs. The reason is that the transferred-in costs are the costs incurred in the assembly department, and any units received 693 www.downloadslide.com 694 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units Using the Weighted-Average Method for the Testing Department for March 2017 exHibit 17-8 $ % & (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given, p. 693) Transferred-in during current period (given, p. 693) To account for Completed and transferred out during current period Work in process, ending a (given, p. 693) (200 3 100%; 200 3 0%; 200 3 80%) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done to date a ' ( (Step 2) Equivalent Units Transferred-In Direct Costs Materials Physical Units 240 400 640 440 200 640 Conversion Costs 440 440 440 200 0 160 640 440 600 Degree of completion in this department: transferred-in costs, 100%; direct materials, 0%; conversion costs, 80%. in the testing department must have first been completed in the assembly department. In contrast, the direct materials costs have a zero degree of completion in both beginning and ending work-in-process inventories because, in the testing department, direct materials are introduced at the end of the process. Exhibit 17-9 describes Steps 3, 4, and 5 for the weighted-average method. Beginning work in process and work done in the current period are combined for the purposes of computing the cost per equivalent unit for the transferred-in costs, direct materials costs, and conversion costs. exHibit 17-9 Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory Using the Weighted-Average Method for the Testing Department for March 2017 $ % (Step 3) Work in process, beginning (given, p. 693) Costs added in current period (given, p. 693) Total costs to account for (Step 4) Costs incurred to date Divide by equivalent units of work done to date (Exhibit 17-8) Cost per equivalent unit of work done to date (Step 5) Assignment of costs: & ' Total Production Costs $ 51,600 113,800 $165,400 Transferred-In Costs $33,600 52,000 $85,600 ( ) 1 1 1 Direct Materials $ 0 13,200 $13,200 * + Conversion Costs 1 $18,000 48,600 1 1 $66,600 $85,600 4 640 $133.75 $13,200 4 440 $ 30.00 $66,600 4 600 $111.00 Completed and transferred out (440 units) Work in process, ending (200 units) Total costs accounted for a Equivalent units completed and transferred out from Exhibit 17-8, Step 2. b Equivalent units in ending work in process from Exhibit 17-8, Step 2. $120,890 44,510 $165,400 a (440 3 $133.75) b (200 3 $133.75) $85,600 1 1 1 a (440 3 $30) b (0 3 $30) $13,200 1 (440a 3 $111) 1 (160b 3 $111) 1 $66,600 www.downloadslide.com transferred-in Costs in ProCess Costing The journal entry for the transfer from testing to Finished Goods (see Exhibit 17-9) is as follows: Finished Goods Control Work in Process—Testing To record cost of goods completed and transferred from testing to Finished Goods. 120,890 120,890 Entries in the Work in Process—Testing account (see Exhibit 17-9) are as follows: Work in Process—Testing Beginning inventory, March 1 51,600 Transferred out Transferred-in costs 52,000 Direct materials 13,200 Conversion costs 48,600 Ending inventory, March 31 120,890 44,510 Transferred-In Costs and the FIFO Method To examine the FIFO process-costing method with transferred-in costs, we again use the fivestep procedure. Exhibit 17-10 shows Steps 1 and 2. Other than accounting for transferred-in costs, computing the equivalent units is the same as under the FIFO method for the assembly department (see Exhibit 17-6). Exhibit 17-11 describes Steps 3, 4, and 5. In Step 3, the $165,880 in total costs to account for under the FIFO method differ from the total costs under the weighted-average method, which are $165,400. This is because of the difference in the costs of completed units transferred in from the assembly department under the two methods—$52,480 under FIFO and exHibit 17-10 Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units Using the FIFO Method for the Testing Department for March 2017 $ % & ' ( (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given, p. 693) Transferred in during current period (given, p. 693) To account for Completed and transferred out during current period: From beginning work in process a [240 3 (100% ] 100%); 240 3 (100% ] 0%); 240 3 (100% ] 62.5%)] Started and completed (2 0 0 3 1 0 0 % ; 2 0 0 3 1 0 0 % ; 2 0 0 3 1 0 0 % ) Work in process, ending c (given, p. 693) (2 0 0 3 1 0 0 % ; 2 0 0 3 0 % ; 2 0 0 3 8 0 % ) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done in current period a (Step 2) Equivalent Units Physical Transferred-In Direct Conversion Units Costs Materials Costs (work done before current period) 240 400 640 240 200b 200 640 0 240 90 200 200 200 200 0 160 400 440 450 Degree of completion in this department: Transferred-in costs, 100%; direct materials, 0%; conversion costs, 62.5%. 440 physical units completed and transferred out minus 240 physical units completed and transferred out from beginning work-in-process inventory. c Degree of completion in this department: Transferred-in costs, 100%; direct materials, 0%; conversion costs, 80%. b 695 www.downloadslide.com 696 ChaPter 17 exHibit 17-11 $ ProCess Costing Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory Using the FIFO Method for the Testing Department for March 2017 % (Step 3) Work in process, beginning (given, p. 693) Costs added in current period (given, p. 693) Total costs to account for & Total Production Costs $ 51,600 114,280 $165,880 ' ( ) Transferred-In Cost 1 $33,600 1 52,480 1 $86,080 * Direct Materials $ 0 13,200 $13,200 + Conversion Costs 1 $18,000 1 48,600 1 $66,600 $52,480 4 400 $131.20 (Step 4) Costs added in current period Divide by equivalent units of work done in current period (Exhibit 17-10) Cost per equivalent unit of work done in current period $13,200 4 440 $ 30 $48,600 4 450 $ 108 (Step 5) Assignment of costs: Completed and transferred out (440 units): Work in process, beginning (240 units) Started and completed (200 units) Total costs of units completed and transferred out Work in process, ending (200 units) Total costs accounted for $33,600 1 (0 3 $131.20) 1 $ 51,600 Costs added to beginning work in process in current period Total from beginning inventory 16,920 68,520 53,840 122,360 43,520 $165,880 a $0 1 a $18,000 a (240 3 $30) 1 (90 3 $108) b b b (200 3 $131.20) 1 (200 3 $30) 1 (200 3 $108) c (200 3 $131.20) 1 $86,080 1 c (0 3 $30) $13,200 c 1 (160 3 $108) 1 $66,600 a Equivalent units used to complete beginning work in process from Exhibit 17-10, Step 2. b Equivalent units started and completed from Exhibit 17-10, Step 2. c Equivalent units in ending work in process from Exhibit 17-10, Step 2. $52,000 under the weighted-average method. The cost per equivalent unit for the current period in Step 4 is calculated on the basis of costs transferred in and work done in the current period only. Step 5 then accounts for the total costs of $165,880 by assigning them to the units transferred out and those in ending work-in-process inventory. Again, other than considering transferred-in costs, the calculations mirror those under the FIFO method for the assembly department (in Exhibit 17-7). Remember that in a series of interdepartmental transfers, each department is regarded as separate and distinct for accounting purposes. The journal entry for the transfer from testing to Finished Goods (see Exhibit 17-11) is as follows: Finished Goods Control Work in Process—Testing To record the cost of goods completed and transferred from testing to Finished Goods. 122,360 122,360 The entries in the Work in Process—Testing account (see Exhibit 17-11) are as follows: Work in Process—Testing Beginning inventory, March 1 51,600 Transferred out Transferred-in costs 52,480 Direct materials 13,200 Conversion costs 48,600 Ending inventory, March 31 43,520 122,360 www.downloadslide.com hyBrid Costing systems 697 Points to Remember About Transferred-In Costs Some points to remember when accounting for transferred-in costs are as follows: 1. Be sure to include the transferred-in costs from previous departments in your calculations. 2. When calculating the costs to be transferred using the FIFO method, do not overlook costs assigned in the previous period to units that were in process at the beginning of the current period but are now included in the units transferred. For example, do not overlook the $51,600 in Exhibit 17-11. 3. Unit costs may fluctuate between periods. Therefore, transferred units may contain batches accumulated at different unit costs. For example, the 400 units transferred in at $52,480 in Exhibit 17-11 using the FIFO method consist of units that have different unit costs of direct materials and conversion costs when these units were worked on in the assembly department (see Exhibit 17-7). Remember, however, that when these units are transferred to the testing department, they are costed at one average unit cost of $131.20 ($52,480 , 400 units), as in Exhibit 17-11. 4. Units may be measured in different denominations in different departments. Consider each department separately. For example, unit costs could be based on kilograms in the first department and liters in the second department. Accordingly, as units are received in the second department, their measurements must be converted to liters. DecisiOn Point How are the weightedaverage and FIFO process-costing methods applied to transferred-in costs? Hybrid Costing Systems Product-costing systems do not always fall neatly into either job-costing or process-costing categories. Many production systems are hybrid systems in which both mass production and customization occur. Consider Ford Motor Company. Automobiles are manufactured in a continuous flow (suited to process costing), but individual units may be customized with different engine sizes, transmissions, music systems, and so on (which requires job costing). A hybrid-costing system blends characteristics from both job-costing and process-costing systems. Managers must design product-costing systems to fit the particular characteristics of different production systems. Firms that manufacture closely related standardized products (for example, various types of televisions, dishwashers, washing machines, and shoes) tend to use hybrid-costing systems. They use process costing to account for the conversion costs and job costing for the material and customizable components. Consider Nike, which has a message for shoppers looking for the hottest new shoe design: Just do it … yourself! Athletic apparel manufacturers have long individually crafted shoes for professional athletes. Now, Nike is making it possible for other customers to design their own shoes and clothing. Using the Internet and mobile applications, Nike’s customers can personalize with their own colors and patterns for Jordanbrand sneakers and other apparel. Concepts in Action: Hybrid Costing for Under Armour 3D Printed Shoes describes customization and the use of a hybrid-costing system at one of Nike’s rivals, Under Armour. The next section explains operation costing, a common type of hybridcosting system. Overview of Operation-Costing Systems An operation is a standardized method or technique performed repetitively, often on different materials, resulting in different finished goods. Multiple operations are usually conducted within a department. For instance, a suit maker may have a cutting operation and a hemming operation within a single department. The term operation, however, is often used loosely. It may be a synonym for a department or process. For example, some companies may call their finishing department a finishing process or a finishing operation. An operation-costing system is a hybrid-costing system applied to batches of similar, but not identical, products. Each batch of products is often a variation of a single design, and it proceeds through a sequence of operations. Within each operation, all product units are treated exactly alike, using identical amounts of the operation’s resources. A key point in the Learning Objective 6 Understand the need for hybrid-costing systems such as operation costing . . . when product-costing does not fall into jobcosting or process-costing categories www.downloadslide.com 698 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing cOncepts in actiOn Hybrid Costing for Under Armour 3D Printed Shoes Under Armour is the fastest-growing sportswear company in the world. Known for its high-tech fitness apparel and celebrity endorsers such as Stephen Curry, in 2016, Under Armour introduced customized, 3D-printed shoes to its product lineup. The Under Armour Architech training shoes feature a 3D-printed midsole that increases stability during exercise. To create the 3D-printed elements, computers create an accurate 3D model of a customer’s foot using photographs taken from multiple angles. Under Armour then prints the midsoles in their Baltimore, Maryland lab and stitches them into the Architech shoes, which are traditionally manufactured ahead of time. The result is a customized pair of shoes tailored for each person’s Ashok Saxena/Alamy Stock Photo unique feet. 3D-printed shoes, like Architech, use a hybrid-costing system. Accounting for the 3D printing of the midsoles and customization requires job costing, but the similar process used to make the shoes they are stitched into lends itself to process costing. The cost of making each pair of shoes is calculated by accumulating all production costs and dividing by the number of shoes made. In other words, while each pair of Architechs is different, the production cost is roughly the same. The combination of mass production with customized parts is called mass customization. 3D printing enables mass customization by allowing customers to tailor specific elements of certain products to their specifications or wants. Along with athletic shoes, 3D printing is letting people create personalized jewelry, earphones, and mobile phone cases. While 3D printing is still in its infancy, by 2020 the market for 3D printers and software is expected to eclipse $20 billion. Sources: Andrew Zaleski, “Here’s Why 2016 Could Be 3D Printing’s Breakout Year,” Fortune (December 30, 2015); John Kell, “Under Armour Debuts First-Ever 3D-Printed Shoes,” Fortune (March 8, 2016); John Brownlee, “What Under Armour’s New 3-D-Printed Shoe Reveals about the Future of Footwear,” Fast Company, Co. Design blog (March 25, 2015); Daniel Burrus, “3D Printed Shoes: A Step in the Right Direction,” Wired (September 2014). operation system is that each batch does not necessarily move through the same operations as other batches. Batches are also called production runs. In a company that makes suits, managers may select a single basic design for every suit to be made, but depending on specifications, each batch of suits varies somewhat from other batches. Batches may vary with respect to the material used or the type of stitching. Semiconductors, textiles, and shoes are also manufactured in batches and may have similar variations from batch to batch. An operation-costing system uses work orders that specify the needed direct materials and step-by-step operations. Product costs are compiled for each work order. Direct materials that are unique to different work orders are specifically identified with the appropriate work order, as in job costing. However, each unit is assumed to use an identical amount of conversion costs for a given operation, as in process costing. A single average conversion cost per unit is calculated for each operation. This is done by dividing the total conversion costs for that operation by the number of units that pass through it. This average cost is then assigned to each unit passing through the operation. Units that do not pass through an operation are not allocated any costs for that operation. There were only two cost categories—direct materials and conversion costs—in the examples we have discussed. However, operation costing can have more than two cost categories. The costs in each category are identified with specific work orders using job-costing or process-costing methods as appropriate. Managers find operation costing useful in cost management because operation costing focuses on control of physical processes, or operations, of a given production system. For example, in clothing manufacturing, managers are concerned with fabric waste, how many fabric layers can be cut at one time, and so on. Operation costing measures, in financial terms, how well managers have controlled physical processes. www.downloadslide.com hyBrid Costing systems Illustrating an Operation-Costing System The Baltimore Clothing Company, a clothing manufacturer, produces two lines of blazers for department stores: those made of wool and those made of polyester. Wool blazers use betterquality materials and undergo more operations than polyester blazers do. The operations information on Work Order 423 for 50 wool blazers and Work Order 424 for 100 polyester blazers is as follows: Direct materials Operations 1. Cutting cloth 2. Checking edges 3. Sewing body 4. Checking seams 5. Machine sewing of collars and lapels 6. Hand sewing of collars and lapels Work Order 423 Wool Satin full lining Bone buttons Work Order 424 Polyester Rayon partial lining Plastic buttons Use Use Use Use Do not use Use Use Do not use Use Do not use Use Do not use The cost data for these work orders, started and completed in March 2017, are as follows: Number of blazers Direct materials costs Conversion costs allocated: Operation 1 Operation 2 Operation 3 Operation 4 Operation 5 Operation 6 Total manufacturing costs Work Order 423 50 $ 6,000 Work Order 424 100 $3,000 580 400 1,900 500 — 700 $10,080 1,160 — 3,800 — 875 — $8,835 As in process costing, all product units in any work order are assumed to consume identical amounts of conversion costs of a particular operation. Baltimore’s operation-costing system uses a budgeted rate to calculate the conversion costs of each operation. The budgeted rate for Operation 1 (amounts assumed) is as follows: Operation 1 budgeted Operation 1 budgeted conversion costs for 2017 conversion@cost = Operation 1 budgeted rate for 2017 product units for 2017 = $232,000 20,000 units = $11.60 per unit The budgeted conversion costs of Operation 1 include labor, power, repairs, supplies, depreciation, and other overhead of this operation. If some units have not been completed (so all units in Operation 1 have not received the same amounts of conversion costs), the conversioncost rate is computed by dividing the budgeted conversion costs by the equivalent units of the conversion costs, as in process costing. As the company manufactures blazers, managers allocate the conversion costs to the work orders processed in Operation 1 by multiplying the $11.60 conversion cost per unit by the number of units processed. Conversion costs of Operation 1 for 50 wool blazers (Work Order 423) are $11.60 per blazer * 50 blazers = $580 and for 100 polyester blazers (Work 699 www.downloadslide.com 700 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing Order 424) are $11.60 per blazer * 100 blazers = $1,160. When equivalent units are used to calculate the conversion-cost rate, costs are allocated to work orders by multiplying the conversion cost per equivalent unit by the number of equivalent units in the work order. The direct materials costs of $6,000 for the 50 wool blazers (Work Order 423) and $3,000 for the 100 polyester blazers (Work Order 424) are specifically identified with each order, as in job costing. The basic point of operation costing is this: Operation unit costs are assumed to be the same regardless of the work order, but direct materials costs vary across orders when the materials for each work order vary. Journal Entries The actual conversion costs for Operation 1 in March 2017—assumed to be $24,400, including the actual costs incurred for Work Order 423 and Work Order 424—are entered into a Conversion Costs Control account: 1. Conversion Costs Control Various accounts (such as Wages Payable Control and Accumulated Depreciation) 24,400 24,400 The summary journal entries for assigning the costs to polyester blazers (Work Order 424) follow. Entries for wool blazers would be similar. Of the $3,000 of direct materials for Work Order 424, $2,975 are used in Operation 1, and the remaining $25 of materials are used in another operation. The journal entry to record direct materials used for the 100 polyester blazers in March 2017 is as follows: 2. Work in Process, Operation 1 Materials Inventory Control 2,975 2,975 The journal entry to record the allocation of conversion costs to products uses the budgeted rate of $11.60 per blazer times the 100 polyester blazers processed, or $1,160: 3. Work in Process, Operation 1 Conversion Costs Allocated 1,160 1,160 The journal entry to record the transfer of the 100 polyester blazers (at a cost of $2,975 + $1,160) from Operation 1 to Operation 3 (polyester blazers do not go through Operation 2) is as follows: 4. Work in Process, Operation 3 Work in Process, Operation 1 4,135 4,135 After posting these entries, the Work in Process, Operation 1, account appears as follows: ② Direct materials ③ Conversion costs allocated Ending inventory, March 31 DecisiOn Point What is an operationcosting system, and when is it a better approach to product costing? Work in Process, Operation 1 2,975 ④ Transferred to Operation 3 1,160 4,135 0 The costs of the blazers are transferred through the operations in which blazers are worked on and then to finished goods in the usual manner. Costs are added throughout the fiscal year in the Conversion Costs Control account and the Conversion Costs Allocated account. Any overallocation or underallocation of conversion costs is disposed of in the same way as overallocated or underallocated manufacturing overhead in a job-costing system, that is, using either the adjusted allocation-rate, proration, or writeoff to cost of goods sold approach (see pages 129–133). www.downloadslide.com ProBlem for self-study Harvest Bakery sells dinner rolls and multigrain bread. The company needs to determine the cost of two work orders for the month of July. Work Order 215 is for 2,400 packages of dinner rolls and Work Order 216 is for 2,800 loaves of multigrain bread. The following information shows the different operations used by the two work orders: Operations 1. Bake 2. Shape loaves 3. Cut rolls Work Order 215 Work Order 216 Use Do not use Use Use Use Do not use 17-4 try it! For July, Harvest Bakery budgeted that it would make 9,600 packages of dinner rolls and 13,000 multigrain loaves (with associated direct materials costs of $5,280 and $11,700, respectively). Budgeted conversion costs for each operation in July were: Baking, $18,080; Shaping, $3,250; and Cutting, $1,440. a. Using the budgeted number of packages as the denominator, calculate the budgeted conversion-cost rates for each operation. b. Using the information in requirement (a), calculate the budgeted cost of goods manufactured for the two July work orders. Problem for self-stuDy Allied Chemicals operates an assembly process as the second of three processes at its plastics plant. Conversion costs are added evenly during the process, while direct materials are added at the end. The following data pertain to the assembly department for June 2017: $ Work in process, beginning inventory Degree of completion, beginning work in process Transferred in during current period Completed and transferred out during current period Work in process, ending inventory Degree of completion, ending work in process % & ' ( Physical Units 50,000 Transferred-In Costs Direct Materials Conversion Costs 100% 0% 80% 100% 0% 40% 200,000 210,000 ? Compute equivalent units under (1) the weighted-average method and (2) the FIFO method. 701 Required www.downloadslide.com 702 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing Solution 1. The weighted-average method uses equivalent units of work done to date to compute cost per equivalent unit. The calculations of equivalent units follow: $ % (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given) Transferred-in during current period (given) To account for Completed and transferred out during current period Work in process, ending a (40,000 3 100%; 40,000 3 0%; 40,000 3 40%) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done to date a b Physical Units 50,000 200,000 250,000 210,000 40,000b 250,000 & ' ( (Step 2) Equivalent Units Transferred-In Direct Conversion Costs Materials Costs 210,000 210,000 210,000 40,000 0 16,000 250,000 210,000 226,000 Degree of completion in this department: Transferred-in costs, 100%; direct materials, 0%; conversion costs, 40%. 250,000 physical units to account for minus 210,000 physical units completed and transferred out. 2. The FIFO method uses equivalent units of work done in the current period only to compute cost per equivalent unit. The calculations of equivalent units follow: $ % (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given) Transferred-in during current period (given) To account for Completed and transferred out during current period: From beginning work in process a [50,0003 (100% ] 100%); 50,000 3(100% ] 0%); 50,000 3(100% ] 80%)] Started and completed (160,000 3 100%; 160,000 3 100%; 160,000 3 100%) Work in process, ending c (40,000 3 100%; 40,000 3 0%; 40,000 3 40%) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done in current period a Physical Units 50,000 200,000 250,000 50,000 160,000b 40,000d 250,000 & ' ( (Step 2) Equivalent Units Transferred-In Direct Conversion Costs Materials Costs 0 50,000 10,000 160,000 160,000 160,000 40,000 0 16,000 200,000 210,000 186,000 Degree of completion in this department: Transferred-in costs, 100%; direct materials, 0%; conversion costs, 80%. 210,000 physical units completed and transferred out minus 50,000 physical units completed and transferred out from beginning work-in-process inventory. c Degree of completion in this department: Transferred-in costs, 100%; direct materials, 0%; conversion costs, 40%. d250,000 physical units to account for minus 210,000 physical units completed and transferred out. b www.downloadslide.com deCision Points 703 DecisiOn Points The following question-and-answer format summarizes the chapter’s learning objectives. Each decision presents a key question related to a learning objective. The guidelines are the answer to that question. Decision Guidelines 1. Under what conditions is a process-costing system used? A process-costing system is used to determine cost of a product or service when masses of identical or similar units are produced. Industries using process-costing systems include the food, textiles, and oil-refining industries. 2. How are average unit costs computed when no inventories are present? Average unit costs are computed by dividing the total costs in a given accounting period by the total units produced in that period. 3. What are the five steps in a process-costing sys- The five steps in a process-costing system are (1) summarize the flow tem, and how are equivalent units calculated? of physical units of output, (2) compute the output in terms of equivalent units, (3) summarize the total costs to account for, (4) compute the cost per equivalent unit, and (5) assign the total costs to units completed and to units in ending work-in-process inventory. An equivalent unit is a derived measure of output that (a) takes the quantity of each input (factor of production) in units completed or in incomplete units in work in process and (b) converts the quantity of input into the amount of completed output units that could be made with that quantity of input. 4. What are the weighted-average and first-in, first-out (FIFO) methods of process costing? Under what conditions will they yield different levels of operating income? The weighted-average method computes unit costs by dividing total costs in the Work in Process account by total equivalent units completed to date and assigns this average cost to units completed and to units in ending work-in-process inventory. The first-in, first-out (FIFO) method computes unit costs based on costs incurred during the current period and equivalent units of work done in the current period. Operating income can differ materially between the two methods when (1) direct material or conversion cost per equivalent unit varies significantly from period to period and (2) physical-inventory levels of work in process are large in relation to the total number of units transferred out of the process. 5. How are the weighted-average and FIFO process-costing methods applied to transferred-in costs? The weighted-average method computes transferred-in costs per unit by dividing the total transferred-in costs to date by the total equivalent transferred-in units completed to date and assigns this average cost to units completed and to units in ending work-in-process inventory. The FIFO method computes the transferred-in costs per unit based on the costs transferred in during the current period and equivalent units of transferred-in costs of work done in the current period. The FIFO method assigns transferred-in costs in the beginning work-in-process inventory to units completed; it assigns costs transferred in during the current period first to complete the beginning inventory, next to start and complete new units, and finally to units in ending work-in-process inventory. 6. What is an operation-costing system, and when Operation costing is a hybrid-costing system that blends characterisis it a better approach to product costing? tics from both job-costing (for direct materials) and process-costing systems (for conversion costs). It is a better approach to product costing when production systems share some features of custom-order manufacturing and other features of mass-production manufacturing. www.downloadslide.com 704 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing aPPenDix Standard-Costing Method of Process Costing Chapter 7 described accounting in a standard-costing system. Recall that this involves making entries using standard costs and then isolating variances from these standards in order to support management control. This appendix describes how the principles of standard costing can be employed in process-costing systems. Benefits of Standard Costing Companies that use process-costing systems produce masses of identical or similar units of output. In such companies, it is fairly easy to budget for the quantities of inputs needed to produce a unit of output. Standard cost per input unit can then be multiplied by input quantity standards to develop a standard cost per output unit. The weighted-average and FIFO methods become very complicated when used in process industries, such as textiles, ceramics, paints, and packaged food, that produce a wide variety of similar products. For example, a steel-rolling mill uses various steel alloys and produces sheets of varying sizes and finishes. The different types of direct materials used and the operations performed are few, but used in various combinations, they yield a wide variety of products. In these cases, if the broad averaging procedure of actual process costing were used, the result would be inaccurate costs for each product. Therefore, managers in these industries typically use the standard-costing method of process costing. Under the standard-costing method, teams of design and process engineers, operations personnel, and management accountants work together to determine separate standard costs per equivalent unit on the basis of different technical processing specifications for each product. Identifying standard costs for each product overcomes the disadvantage of costing all products at a single average amount, as under actual costing. Computations Under Standard Costing We return to the assembly department of Pacific Electronics, but this time we use standard costs. Assume the same standard costs apply in February and March 2017. Data for the assembly department are as follows: $ % Physical Units (SG-40s) (1) Standard cost per unit & Direct Materials (2) $ 74 225 Work in process, beginning inventory (March 1) 100% Degree of completion of beginning work in process Beginning work-in-process inventory at standard costs $16,650a 275 Started during March 400 Completed and transferred out during March 100 Work in process, ending inventory (March 31) Degree of completion of ending work in process 100% $19,800 Actual total costs added during March a Work in process, beginning inventory at standard costs: Direct materials: 225 physical units 3 100% completed 3 $74 per unit 5 $16,650 ' Conversion Costs (3) $ 54 ( Total Costs (4) 5 (2) 1 (3) 60% a $ 7,290 $23,940 50% $16,380 $36,180 Conversion costs: 225 physical units 3 60% completed 3 $54 per unit 5 $7,290 We illustrate the standard-costing method of process costing using the five-step procedure introduced earlier (page 679). www.downloadslide.com aPPendix 705 exHibit 17-12 $ % (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given, p. 704) Started during current period (given, p. 704) To account for Completed and transferred out during current period: From beginning work in process a [225 3 (100% ] 100%); 225 3 (100% ] 60%)] Started and completed (1 7 5 3 1 0 0 % ; 1 7 5 3 1 0 0 % ) Work in process, ending c (given, p. 704) (1 0 0 3 1 0 0 % ; 1 0 0 3 5 0 % ) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done in current period Physical Units 225 275 500 225 175b 100 500 & ' (Step 2) Equivalent Units Direct Conversion Materials Costs 0 90 175 175 100 50 275 315 a Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 60%. 400 physical units completed and transferred out minus 225 physical units completed and transferred out from beginning work-in-process inventory. c Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. b Exhibit 17-12 presents Steps 1 and 2. These steps are identical to the steps described for the FIFO method in Exhibit 17-6 because, as in FIFO, the standard-costing method also assumes that the earliest equivalent units in beginning work in process are completed first. Work done in the current period for direct materials is 275 equivalent units. Work done in the current period for conversion costs is 315 equivalent units. Exhibit 17-13 describes Steps 3, 4, and 5. In Step 3, total costs to account for (that is, the total debits to Work in Process—Assembly) differ from total debits to Work in Process— Assembly under the actual-cost-based weighted-average and FIFO methods. That’s because, as in all standard-costing systems, the debits to the Work in Process account are at standard costs, rather than actual costs. These standard costs total $61,300 in Exhibit 17-13. In Step 4, costs per equivalent unit are standard costs: direct materials, $74, and conversion costs, $54. Therefore, costs per equivalent unit do not have to be computed as they were for the weightedaverage and FIFO methods. Exhibit 17-13, Step 5, assigns total costs to units completed and transferred out and to units in ending work-in-process inventory, as in the FIFO method. Step 5 assigns amounts of standard costs to equivalent units calculated in Exhibit 17-12. These costs are assigned (1) first to complete beginning work-in-process inventory, (2) next to start and complete new units, and (3) finally to start new units that are in ending work-in-process inventory. Note how the $61,300 total costs accounted for in Step 5 of Exhibit 17-13 equal total costs to account for. Accounting for Variances Process-costing systems using standard costs record actual direct materials costs in Direct Materials Control and actual conversion costs in Conversion Costs Control (similar to Variable and Fixed Overhead Control in Chapter 8). In the journal entries that follow, the first two record these actual costs. In entries 3 and 4a, the Work-in-Process—Assembly account Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units Using the StandardCosting Method for the Assembly Department for March 2017 www.downloadslide.com 706 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing exHibit 17-13 $ Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory Using the Standard-Costing Method for the Assembly Department for March 2017 % & ' Total Production Costs $23,940 37,360 $61,300 Direct Materials (225 3 $74) (275 3 $74) $37,000 (Step 3) Work in process, beginning Costs added in current period at standard costs Total costs to account for (Step 4) Standard cost per equivalent unit (given, p. 704) $ (Step 5) Assignment of costs at standard costs: Completed and transferred out (400 units): Work in process, beginning (225 units) Costs added to beginning work in process in current period Total from beginning inventory Started and completed (175 units) $23,940 4,860 28,800 22,400 Total costs of units completed and transferred out 51,200 ( ) * 1 1 1 Conversion Costs (135 3 $54) (315 3 $54) $24,300 128 $ 74 1 $ 54 Work in process, ending (100 units) Total costs accounted for 10,100 $61,300 (225 3 $74) (0 a 3 $74) 1 1 (135 3 $54) (90a 3 $54) (175b 3 $74) 1 (175b 3 $54) (100 c 3 $74) $37,000 1 1 (50c 3 $54) $24,300 F $17,010 $16,380 $ 630 Summary of variances for current performance: Costs added in current period at standard costsd Actual costs incurred (given, p. 704) Variance $20,350 $19,800 $ 550 F a b d Equivalent units used to complete beginning work in process from Exhibit 17-12, Step 2. Equivalent units started and completed from Exhibit 17-12, Step 2. c Equivalent units in ending work in process from Exhibit 17-12, Step 2. From Step 3 above: Direct Materials: (275 3 $74); Conversion Costs: (315 3 $54) accumulates direct materials costs and conversion costs at standard costs. Entries 3 and 4b isolate total variances. The final entry transfers out completed goods at standard costs. 1. Assembly Department Direct Materials Control (at actual costs) Accounts Payable Control To record the direct materials purchased and used in production during March. This cost control account is debited with actual costs. 2. Assembly Department Conversion Costs Control (at actual costs) Various accounts such as Wages Payable Control and Accumulated Depreciation To record the assembly department conversion costs for March. This cost control account is debited with actual costs. Entries 3, 4, and 5 use standard cost amounts from Exhibit 17-13. 3. Work in Process—Assembly (at standard costs) Direct Materials Variances Assembly Department Direct Materials Control To record the standard costs of direct materials assigned to units worked on and total direct materials variances. 19,800 19,800 16,380 16,380 20,350 550 19,800 www.downloadslide.com aPPendix 4a. Work in Process—Assembly (at standard costs) Assembly Department Conversion Costs Allocated To record the conversion costs allocated at standard rates to the units worked on during March. 4b. Assembly Department Conversion Costs Allocated Conversion Costs Variances Assembly Department Conversion Costs Control To record the total conversion costs variances. 5. Work in Process—Testing (at standard costs) Work in Process—Assembly (at standard costs) To record the standard costs of units completed and transferred out from assembly to testing. 17,010 17,010 17,010 630 16,380 51,200 51,200 Variances arise under standard costing, as in entries 3 and 4b. That’s because the standard costs assigned to products on the basis of work done in the current period do not equal actual costs incurred in the current period. Recall that variances that result in higher income than expected are termed favorable, while those that reduce income are unfavorable. From an accounting standpoint, favorable cost variances are credit entries, while unfavorable ones are debits. In the preceding example, both direct materials and conversion cost variances are favorable. This is also reflected in the “F” designations for both variances in Exhibit 17-13. Variances can be analyzed in little or great detail for planning and control purposes, as described in Chapters 7 and 8. Sometimes direct materials price variances are isolated at the time direct materials are purchased and only efficiency variances are computed in entry 3. Exhibit 17-14 shows how the costs flow through the general-ledger accounts under standard costing. Flow of Standard Costs in a Process-Costing System for the Assembly Department for March 2017 exHibit 17-14 Assembly Department Direct Materials Control 19,800 19,800 Work in Process—Assembly Bal. 23,940 20,350 4a 17,010 51,200 Work in Process—Testing 51,200 Transferred out to Finished Goods xx Bal. 10,100 Assembly Department Conversion Costs Control 16,380 4b Direct Materials Variances 16,380 550 Finished Goods xx Cost of Goods Sold Assembly Department Conversion Costs Allocated 4b 17,010 4a 17,010 Accounts Payable Control 19,800 Various Accounts 16,380 Conversion Costs Variances 4b 630 Cost of Goods Sold xx xx 707 www.downloadslide.com 708 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing terms to learn This chapter and the Glossary at the end of the book contain definitions of the following important terms: equivalent units (p. 679) first-in, first-out (FIFO) process-costing method (p. 687) hybrid-costing system (p. 697) operation (p. 697) operation-costing system (p. 697) previous-department costs (p. 692) transferred-in costs (p. 692) weighted-average process-costing method (p. 684) assignment material MyAccountingLab Questions 17-1 17-2 17-3 17-4 17-5 17-6 17-7 17-8 17-9 17-10 17-11 17-12 17-13 17-14 17-15 MyAccountingLab Give three examples of industries that use process-costing systems. In process costing, why are costs often divided into two main classifications? Explain equivalent units. Why are equivalent-unit calculations necessary in process costing? What problems might arise in estimating the degree of completion of semiconductor chips in a semiconductor plant? Name the five steps in process costing when equivalent units are computed. Name the three inventory methods commonly associated with process costing. Describe the distinctive characteristic of weighted-average computations in assigning costs to units completed and to units in ending work in process. Describe the distinctive characteristic of FIFO computations in assigning costs to units completed and to units in ending work in process. Why should the FIFO method be called a modified or department FIFO method? Identify a major advantage of the FIFO method for purposes of planning and control. Identify the main difference between journal entries in process costing and job costing. “The standard-costing method is particularly applicable to process-costing situations.” Do you agree? Why? Why should the accountant distinguish between transferred-in costs and additional direct materials costs for each subsequent department in a process-costing system? “Transferred-in costs are those costs incurred in the preceding accounting period.” Do you agree? Explain. “There’s no reason for me to get excited about the choice between the weighted-average and FIFO methods in my process-costing system. I have long-term contracts with my materials suppliers at fixed prices.” Do you agree with this statement made by a plant controller? Explain. Multiple-Choice Questions In partnership with: 17-16 Assuming beginning work in process is zero, the equivalent units of production computed using FIFO versus weighted average will have the following relationship: 1. FIFO equivalent units will be greater than weighted-average equivalent units. 2. FIFO equivalent units will be less than weighted-average equivalent units. 3. Weighted-average equivalent units are always greater than FIFO equivalent units. 4. Weighted-average equivalent units will be equal to FIFO equivalent units. 17-17 The following information concerns Westheimer Corporation’s equivalent units in May 20X1: Beginning work-in-process (50% complete) Units started during May Units completed and transferred Ending work-in-process (80% complete) Units 4,000 16,000 14,000 6,000 www.downloadslide.com assignment material Using the weighted-average method, what were Westheimer’s May 20X1 equivalent units? 1. 14,000 2. 18,800 3. 20,000 4. 39,000 17-18 Sepulveda Corporation uses a process costing system to manufacture laptop PCs. The following information summarizes operations for its VeryLite model during the quarter ending March 31, Year 1: Work-in-process inventory, January 1 Started during the quarter Completed during the quarter Work-in-process inventory, March 31 Costs added during the quarter Units 100 500 400 200 Direct Materials $ 60,000 $840,000 Beginning work-in-process inventory was 50% complete for direct materials. Ending work-in-process inventory was 75% complete for direct materials. What were the equivalent units for direct materials for the quarter using the FIFO method? 1. 450 2. 500 3. 550 4. 600 17-19 Penn Manufacturing Corporation uses a process-costing system to manufacture printers for PCs. The following information summarizes operations for its NoToner model during the quarter ending September 30, Year 1: Work-in-process inventory, July 1 Started during the quarter Completed during the quarter Work-in-process inventory, September 30 Costs added during the quarter Units 100 500 400 200 Direct Labor $ 50,000 $775,000 Beginning work-in-process inventory was 50% complete for direct labor. Ending work-in-process inventory was 75% complete for direct labor. What is the total value of the direct labor in the ending work-in-process inventory using the weighted-average method? 1. $183,000 2. $194,000 3. $225,000 4. $210,000 17-20 Kimberly Manufacturing uses a process-costing system to manufacture Dust Density Sensors for the mining industry. The following information pertains to operations for the month of May, Year 5. Beginning work-in-process inventory, May 1 Started in production during May Completed production during May Ending work-in-process inventory, May 31 Units 16,000 100,000 92,000 24,000 The beginning inventory was 60% complete for materials and 20% complete for conversion costs. The ending inventory was 90% complete for materials and 40% complete for conversion costs. Costs pertaining to the month of May are as follows. • Beginning inventory costs are: materials, $54,560; direct labor $20,320; and factory overhead, $15,240. • Costs incurred during May are: materials used, $468,000; direct labor, $182,880; and factory overhead, $391,160. Using the weighted-average method, the equivalent-unit conversion cost for May is: 1. $5.65 2. $5.83 3. $6.00 4. $6.41 ©2016 DeVry/Becker Educational Development Corp. All Rights Reserved. 709 www.downloadslide.com 710 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing MyAccountingLab Exercises 17-21 Equivalent units, zero beginning inventory. Candid, Inc. is a manufacturer of digital cameras. It has two departments: assembly and testing. In January 2017, the company incurred $800,000 on direct materials and $805,000 on conversion costs, for a total manufacturing cost of $1,605,000. Required 1. Assume there was no beginning inventory of any kind on January 1, 2017. During January, 5,000 cameras were placed into production and all 5,000 were fully completed at the end of the month. What is the unit cost of an assembled camera in January? 2. Assume that during February 5,000 cameras are placed into production. Further assume the same total assembly costs for January are also incurred in February, but only 4,000 cameras are fully completed at the end of the month. All direct materials have been added to the remaining 1,000 cameras. However, on average, these remaining 1,000 cameras are only 60% complete as to conversion costs. (a) What are the equivalent units for direct materials and conversion costs and their respective costs per equivalent unit for February? (b) What is the unit cost of an assembled camera in February 2017? 3. Explain the difference in your answers to requirements 1 and 2. Required Prepare summary journal entries for the use of direct materials and incurrence of conversion costs. Also prepare a journal entry to transfer out the cost of goods completed. Show the postings to the Work in Process account. 17-22 Journal entries (continuation of 17-21). Refer to requirement 2 of Exercise 17-21. 17-23 Zero beginning inventory, materials introduced in middle of process. Dot and Ken Ice Cream uses a mixing department and a freezing department in producing its ice cream. Its process-costing system in the mixing department has two direct materials cost categories (ice cream mix and flavorings) and one conversion cost pool. The following data pertain to the mixing department for April 2017: Work in process, April 1 Started in April Completed and transferred to freezing Costs: Ice cream mix Flavorings Conversion costs 0 10,000 gallons 8,500 gallons $27,000 $ 4,080 $53,700 The ice cream mix is introduced at the start of operations in the mixing department, and the flavorings are added when the product is 40% completed in the mixing department. Conversion costs are added evenly during the process. The ending work in process in the mixing department is 30% complete. Required 1. Compute the equivalent units in the mixing department for April 2017 for each cost category. 2. Compute (a) the cost of goods completed and transferred to the freezing department during April and (b) the cost of work in process as of April 30, 2017. 17-24 Weighted-average method, equivalent units. The assembly division of Quality Time Pieces, Inc. uses the weighted-average method of process costing. Consider the following data for the month of May 2017: Beginning work in process (May 1)a Started in May 2017 Completed during May 2017 Ending work in process (May 31)b Total costs added during May 2017 a b Required Physical Units (Watches) 100 510 450 160 Direct Materials $ 459,888 Conversion Costs $ 142,570 $3,237,000 $1,916,000 Degree of completion: direct materials, 80%; conversion costs, 35%. Degree of completion: direct materials, 80%; conversion costs, 40%. Compute equivalent units for direct materials and conversion costs. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. 17-25 Weighted-average method, assigning costs (continuation of 17-24). Required For the data in Exercise 17-24, summarize the total costs to account for, calculate the cost per equivalent unit for direct materials and conversion costs, and assign costs to the units completed (and transferred out) and units in ending work in process. www.downloadslide.com assignment material 17-26 FIFO method, equivalent units. Refer to the information in Exercise 17-24. Suppose the assembly division at Quality Time Pieces, Inc. uses the FIFO method of process costing instead of the weightedaverage method. Compute equivalent units for direct materials and conversion costs. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. Required 17-27 FIFO method, assigning costs (continuation of 17-26). For the data in Exercise 17-24, use the FIFO method to summarize the total costs to account for, calculate the cost per equivalent unit for direct materials and conversion costs, and assign costs to units completed (and transferred out) and to units in ending work in process. Required 17-28 Operation costing. The Carter Furniture Company needs to determine the cost of two work orders for December 2017. Work Order 1200A is for 250 painted, unassembled chests and Work Order 1250A is for 400 stained, assembled chests. The following information pertains to these two work orders: Number of chests Operations 1. Cutting 2. Painting 3. Staining 4. Assembling 6. Packaging Work Order 1200A 250 Work Order 1250A 400 Use Use Do not use Do not use Use Use Do not use Use Use Use Selected budget information for December follows: Chests Direct materials costs Unassembled Chests 800 $52,000 Assembled Chests 1,500 $180,000 Total 2,300 $232,000 Budgeted conversion costs for each operation for December follow: Cutting Painting Staining Assembling Packaging $41,400 6,400 24,000 33,000 11,500 1. Using budgeted number of chests as the denominator, calculate the budgeted conversion-cost rates for each operation. 2. Using the information in requirement 1, calculate the budgeted cost of goods manufactured for the two December work orders. 3. Calculate the cost per unassembled chest and assembled chest for Work Order 1200A and Work Order 1250A, respectively. 17-29 Weighted-average method, assigning costs. ZanyBrainy Corporation makes interlocking children’s blocks in a single processing department. Direct materials are added at the start of production. Conversion costs are added evenly throughout production. ZanyBrainy uses the weighted-average method of process costing. The following information for October 2017 is available. Work in process, October 1 Started in October Completed and transferred out during October Work in process, October 31 a Physical Units 12,000a 48,000 55,000 5,000b Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 80%. Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 30%. b Equivalent Units Direct Conversion Materials Costs 12,000 9,600 55,000 5,000 55,000 1,500 Required 711 www.downloadslide.com 712 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing Total Costs for October 2017 Work in process, beginning Direct materials Conversion costs Direct materials added during October Conversion costs added during October Total costs to account for Required $ 5,760 14,825 $ 20,585 25,440 58,625 $104,650 1. Calculate the cost per equivalent unit for direct materials and conversion costs. 2. Summarize the total costs to account for, and assign them to units completed (and transferred out) and to units in ending work in process. 17-30 FIFO method, assigning costs. Required 1. Do Exercise 17-29 using the FIFO method. 2. ZanyBrainy’s management seeks to have a more consistent cost per equivalent unit. Which method of process costing should the company choose and why? 17-31 Transferred-in costs, weighted-average method. Trendy Clothing, Inc. is a manufacturer of winter clothes. It has a knitting department and a finishing department. This exercise focuses on the finishing department. Direct materials are added at the end of the process. Conversion costs are added evenly during the process. Trendy uses the weighted-average method of process costing. The following information for June 2017 is available. $ Required Work in process, beginning inventory (June 1) Degree of completion, beginning work in process Transferred-in during June Completed and transferred out during June Work in process, ending inventory (June 30) Degree of completion, ending work in process Total costs added during June % & Physical Units Transferred-In (tons) Costs 60 $ 60,000 100% 100 120 40 100% $117,000 ' ( Direct Materials 0 $ 0% Conversion Costs $24,000 50% 0% $27,000 75% $62,400 1. Calculate equivalent units of transferred-in costs, direct materials, and conversion costs. 2. Summarize the total costs to account for, and calculate the cost per equivalent unit for transferred-in costs, direct materials, and conversion costs. 3. Assign costs to units completed (and transferred out) and to units in ending work in process. 17-32 Transferred-in costs, FIFO method. Refer to the information in Exercise 17-31. Suppose that Trendy uses the FIFO method instead of the weighted-average method in all of its departments. The only changes to Exercise 17-31 under the FIFO method are that total transferred-in costs of beginning work in process on June 1 are $45,000 (instead of $60,000) and total transferred-in costs added during June are $114,000 (instead of $117,000). Required Do Exercise 17-31 using the FIFO method. Note that you first need to calculate equivalent units of work done in the current period (for transferred-in costs, direct materials, and conversion costs) to complete beginning work in process, to start and complete new units, and to produce ending work in process. 17-33 Operation costing. Egyptian Spa produces two different spa products: Relax and Refresh. The company uses three operations to manufacture the products: mixing, blending, and packaging. Because of the materials used, Relax is produced in powder form in the mixing department, then transferred to the blending department, and finally on to packaging. Refresh undergoes no mixing; it is produced in liquid form in the blending department and then transferred to packaging. Egyptian Spa applies conversion costs based on labor-hours in the mixing department. It takes 3 minutes to mix the ingredients for a container of Relax. Conversion costs are applied based on the number of containers in the blending departments and on the basis of machine-hours in the packaging department. It takes 0.5 minutes of machine time to fill a container, regardless of the product. www.downloadslide.com assignment material 713 The budgeted number of containers and expected direct materials cost for each product are as follows: Number of containers Direct materials cost Relax 24,000 $17,160 Refresh 18,000 $13,140 The budgeted conversion costs for each department for May are as follows: Department Mixing Blending Packaging Allocation of Conversion Costs Direct labor-hours Number of containers Machine-hours Budgeted Conversion Cost $11,760 $20,160 $ 2,800 1. Calculate the conversion cost rates for each department. 2. Calculate the budgeted cost of goods manufactured for Relax and Refresh for the month of May. 3. Calculate the cost per container for each product for the month of May. Required 17-34 Standard-costing with beginning and ending work in process. Lawrence Company is a manufacturer of contemporary door handles. The vice president of Design attends home shows twice a year so the company can keep current with home trends. Because of its volume, Lawrence uses process costing to account for production. Costs and output figures for August are as follows: Lawrence Company’s Process Costing for the Month Ended August 31, 2017 Units Standard cost per unit Work in process, beginning inventory (Aug. 1) Degree of completion of beginning work in process Started in August Completed and transferred out Work in process, ending inventory (Aug. 31) Degree of completion of ending work in process Total costs added during August 15,000 Direct Materials $ 5.75 $ 86,250 100% Conversion Costs $ 12.25 $ 55,125 30% 100% $569,000 80% $1,307,240 100,000 95,000 20,000 1. Compute equivalent units for direct materials and conversion costs. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. 2. Compute the total standard costs of handles transferred out in August and the total standard costs of the August 31 inventory of work in process. 3. Compute the total August variances for direct materials and conversion costs. 4. Prepare summarized journal entries to record both the actual costs and standard costs for direct materials and conversion costs, including the variances for both production costs. Problems 17-35 Equivalent units, comprehensive. Louisville Sports manufactures baseball bats for use by players in the major leagues. A critical requirement for elite players is that each bat they use have an identical look and feel. As a result, Louisville uses a dedicated process to produce bats to each player’s specifications. One of Louisville’s key clients is Ryan Brown of the Green Bay Brewers. Producing his bat involves the use of three materials—ash, cork, and ink—and a sequence of 20 standardized steps. Materials are added as follows: Ash: This is the basic wood used in bats. Eighty percent of the ash content is added at the start of the process; the rest is added at the start of the 16th step of the process. Cork: This is inserted into the bat in order to increase Ryan’s bat speed. Half of the cork is introduced at the beginning of the seventh step of the process; the rest is added at the beginning of the 14th step. Ink: This is used to stamp Ryan’s name on the finished bat and is added at the end of the process. Of the total conversion costs, 6% are added during each of the first 10 steps of the process, and 4% are added at each of the remaining 10 steps. Required MyAccountingLab www.downloadslide.com 714 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing On May 1, 2017, Louisville had 100 bats in inventory. These bats had completed the ninth step of the process as of April 30, 2017. During May, Louisville put another 60 bats into production. At the end of May, Louisville was left with 40 bats that had completed the 12th step of the production process. Required 1. Under the weighted-average method of process costing, compute equivalent units of work done for each relevant input for the month of May. 2. Under the FIFO method of process costing, compute equivalent units of work done for each relevant input for the month of May. 17-36 Weighted-average method. Hoffman Company manufactures car seats in its Boise plant. Each car seat passes through the assembly department and the testing department. This problem focuses on the assembly department. The process-costing system at Hoffman Company has a single direct-cost category (direct materials) and a single indirect-cost category (conversion costs). Direct materials are added at the beginning of the process. Conversion costs are added evenly during the process. When the assembly department finishes work on each car seat, it is immediately transferred to testing. Hoffman Company uses the weighted-average method of process costing. Data for the assembly department for October 2017 are as follows: Work in process, October 1a Started during October 2017 Completed during October 2017 Work in process, October 31b Total costs added during October 2017 Physical Units (Car Seats) 4,000 22,500 26,000 500 Direct Materials $1,248,000 Conversion Costs $ 241,650 $4,635,000 $2,575,125 a Degree of completion: direct materials,?%; conversion costs, 45%. Degree of completion: direct materials,?%; conversion costs, 65%. b Required 1. For each cost category, compute equivalent units in the assembly department. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. 2. What issues should the manager focus on when reviewing the equivalent-unit calculations? 3. For each cost category, summarize total assembly department costs for October 2017 and calculate the cost per equivalent unit. 4. Assign costs to units completed and transferred out and to units in ending work in process. Required Prepare a set of summarized journal entries for all October 2017 transactions affecting Work in Process— Assembly. Set up a T-account for Work in Process—Assembly and post your entries to it. 17-37 Journal entries (continuation of 17-36). 17-38 FIFO method (continuation of 17-36). Required 1. Do Problem 17-36 using the FIFO method of process costing. Explain any difference between the cost per equivalent unit in the assembly department under the weighted-average method and the FIFO method. 2. Should Hoffman’s managers choose the weighted-average method or the FIFO method? Explain briefly. 17-39 Transferred-in costs, weighted-average method (related to 17-36 to 17-38). Hoffman Company, as you know, is a manufacturer of car seats. Each car seat passes through the assembly department and testing department. This problem focuses on the testing department. Direct materials are added when the testing department process is 90% complete. Conversion costs are added evenly during the testing department’s process. As work in assembly is completed, each unit is immediately transferred to testing. As each unit is completed in testing, it is immediately transferred to Finished Goods. Hoffman Company uses the weighted-average method of process costing. Data for the testing department for October 2017 are as follows: Work in process, October 1a Transferred in during October 2017 Completed during October 2017 Work in process, October 31b Total costs added during October 2017 a Physical Units (Car Seats) 5,500 ? 29,800 1,700 TransferredIn Costs $2,931,000 Direct Materials $ 0 Conversion Costs $ 499,790 $8,094,000 $10,877,000 $4,696,260 Degree of completion: transferred-in costs,?%; direct materials,?%; conversion costs, 65%. Degree of completion: transferred-in costs,?%; direct materials,?%; conversion costs, 45%. b www.downloadslide.com assignment material 1. What is the percentage of completion for (a) transferred-in costs and direct materials in beginning work-in-process inventory and (b) transferred-in costs and direct materials in ending work-in-process inventory? 2. For each cost category, compute equivalent units in the testing department. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. 3. For each cost category, summarize total testing department costs for October 2017, calculate the cost per equivalent unit, and assign costs to units completed (and transferred out) and to units in ending work in process. 4. Prepare journal entries for October transfers from the assembly department to the testing department and from the testing department to Finished Goods. Required 17-40 Transferred-in costs, FIFO method (continuation of 17-39). Refer to the information in Problem 17-39. Suppose that Hoffman Company uses the FIFO method instead of the weighted-average method in all of its departments. The only changes to Problem 17-39 under the FIFO method are that total transferred-in costs of beginning work in process on October 1 are $2,879,000 (instead of $2,931,000) and that total transferred-in costs added during October are $9,048,000 (instead of $8,094,000). Required Using the FIFO process-costing method, complete Problem 17-39. 17-41 Weighted-average method. McKnight Handcraft is a manufacturer of picture frames for large retailers. Every picture frame passes through two departments: the assembly department and the finishing department. This problem focuses on the assembly department. The process-costing system at McKnight has a single direct-cost category (direct materials) and a single indirect-cost category (conversion costs). Direct materials are added when the assembly department process is 10% complete. Conversion costs are added evenly during the assembly department’s process. McKnight uses the weighted-average method of process costing. Consider the following data for the assembly department in April 2017: Work in process, April 1a Started during April 2017 Completed during April 2017 Work in process, April 30b Total costs added during April 2017 Physical Unit (Frames) 60 510 450 120 Direct Materials $ 1,530 Conversion Costs $ 156 $17,850 $11,544 a Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 40%. Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 15%. b 1. Summarize the total assembly department costs for April 2017, and assign them to units completed (and transferred out) and to units in ending work in process. 2. What issues should a manager focus on when reviewing the equivalent units calculation? Required 17-42 FIFO method (continuation of 17-41). 1. Complete Problem 17-41 using the FIFO method of process costing. 2. If you did Problem 17-41, explain any difference between the cost of work completed and transferred out and the cost of ending work in process in the assembly department under the weighted-average method and the FIFO method. Should McKnight’s managers choose the weighted-average method or the FIFO method? Explain briefly. 17-43 Transferred-in costs, weighted-average method. Spelling Sports, which produces basketballs, has two departments: cutting and stitching. Each department has one direct-cost category (direct materials) and one indirect-cost category (conversion costs). This problem focuses on the stitching department. Basketballs that have undergone the cutting process are immediately transferred to the stitching department. Direct material is added when the stitching process is 70% complete. Conversion costs are added evenly during stitching operations. When those operations are done, the basketballs are immediately transferred to Finished Goods. Required 715 www.downloadslide.com 716 ChaPter 17 ProCess Costing Spelling Sports uses the weighted-average method of process costing. The following is a summary of the March 2017 operations of the stitching department: A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Required Beginning work in process Degree of completion, beginning work in process Transferred in during March 2017 Completed and transferred out during March 2017 Ending work in process, March 31 Degree of completion, ending work in process Total costs added during March B C Physical Units Transferred-In (basketballs) Costs 17,500 $ 45,360 100% 56,000 52,000 21,500 100% $154,560 D E Direct Materials 0 $ 0% Conversion Costs $17,660 60% 0% $28,080 20% $89,310 1. Summarize total stitching department costs for March 2017, and assign these costs to units completed (and transferred out) and to units in ending work in process. 2. Prepare journal entries for March transfers from the cutting department to the stitching department and from the stitching department to Finished Goods. 17-44 Transferred-in costs, FIFO method. Refer to the information in Problem 17-43. Suppose that Spelling Sports uses the FIFO method instead of the weighted-average method. Assume that all other information, including the cost of beginning WIP, is unchanged. Required 1. Using the FIFO process-costing method, complete Problem 17-43. 2. If you did Problem 17-43, explain any difference between the cost of work completed and transferred out and the cost of ending work in process in the stitching department under the weighted-average method and the FIFO method. 17-45 Standard costing, journal entries. The Warner Company manufactures reproductions of expensive sunglasses. Warner uses the standard-costing method of process costing to account for the production of the sunglasses. All materials are added at the beginning of production. The costs and output of sunglasses for May 2017 are as follows: Work in process, beginning Started during May Completed and transferred out Work in process, ending Standard cost per unit Costs added during May Required Physical Units 22,000 95,000 87,000 30,000 % of Completion for Conversion Costs 60% Direct Materials $ 48,400 Conversion Costs $ 33,000 $ 2.20 $207,500 $ 2.50 $238,000 75% 1. Compute equivalent units for direct materials and conversion costs. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. 2. Compute the total standard costs of sunglasses transferred out in May and the total standard costs of the May 31 inventory of work in process. 3. Compute the total May variances for direct materials and conversion costs. 4. Prepare summarized journal entries to record both the actual costs and standard costs for direct materials and conversion costs, including the variances for both production costs. 17-46 Multiple processes or operations, costing. The Sedona Company is dedicated to making products that meet the needs of customers in a sustainable manner. Sedona is best known for its KLN water bottle, which is a BPA-free, dishwasher-safe, bubbly glass bottle in a soft silicone sleeve. The production process consists of three basic operations. In the first operation, the glass is formed by remelting cullets (broken or refuse glass). In the second operation, the glass is assembled with the silicone gasket and sleeve. The resulting product is finished in the final operation with the addition of the polypropylene cap. Consulting studies have indicated that of the total conversion costs required to complete a finished unit, the forming operation requires 60%, the assembly 30%, and the finishing 10%. www.downloadslide.com assignment material The following data are available for March 2017 (there is no opening inventory of any kind): Cullets purchased Silicone purchased Polypropylene used Total conversion costs incurred Ending inventory, cullets Ending inventory, silicone Number of bottles completed and transferred Inventory in process at the end of the month: Units formed but not assembled Units assembled but not finished $67,500 $24,000 $ 6,000 $68,850 $ 4,500 $ 3,000 12,000 4,000 2,000 1. What is the cost per equivalent unit for conversion costs for KLN bottles in March 2017? 2. Compute the cost per equivalent unit with respect to each of the three materials: cullets, silicone, and polypropylene. 3. What is the cost of goods completed and transferred out? 4. What is the cost of goods formed but not assembled? 5. What is the cost of goods assembled but not finished? Required 17-47 Benchmarking, ethics. Amanda McNall is the corporate controller of Scott Quarry. Scott Quarry operates 12 rock-crushing plants in Scott County, Kentucky, that process huge chunks of limestone rock extracted from underground mines. Given the competitive landscape for pricing, Scott’s managers pay close attention to costs. Each plant uses a process-costing system, and at the end of every quarter, each plant manager submits a production report and a production-cost report. The production report includes the plant manager’s estimate of the percentage of completion of the ending work in process as to direct materials and conversion costs, as well as the level of processed limestone inventory. McNall uses these estimates to compute the cost per equivalent unit of work done for each input for the quarter. Plants are ranked from 1 to 12, and the three plants with the lowest cost per equivalent unit for direct materials and conversion costs are each given a bonus and recognized in the company newsletter. McNall has been pleased with the success of her benchmarking program. However, she has recently received anonymous e-mails that two plant managers have been manipulating their monthly estimates of percentage of completion in an attempt to obtain the bonus. 1. Why and how might managers manipulate their monthly estimates of percentage of completion and level of inventory? 2. McNall’s first reaction is to contact each plant controller and discuss the problem raised by the anonymous communications. Is that a good idea? 3. Assume that each plant controller’s primary reporting responsibility is to the plant manager and that each plant controller receives the phone call from McNall mentioned in requirement 2. What is the ethical responsibility of each plant controller (a) to Amanda McNall and (b) to Scott Quarry in relation to the equivalent-unit and inventory information each plant provides? 4. How might McNall learn whether the data provided by particular plants are being manipulated? Required 717 www.downloadslide.com 18 Spoilage, Rework, and Scrap Learning Objectives 1 Understand the definitions of spoilage, rework, and scrap 2 Identify the differences between normal and abnormal spoilage 3 Account for spoilage in process costing using the weightedaverage method and the first-in, first-out (FIFO) method 4 5 6 7 Account for spoilage at various stages of completion in process costing Account for spoilage in job costing Account for rework in job costing Account for scrap When a product doesn’t meet specification but is subsequently repaired and sold, it is called rework. Companies try to minimize rework, as well as spoilage and scrap, during production. Why? Because higher-than-normal levels of spoilage and scrap can have a significant negative effect on a company’s profits. Rework can also cause companies to incur substantial costs over many years, as the following article about Honda shows. AirbAg rework SinkS HondA’S record YeAr1 In 2015, Japanese automobile manufacturer Honda Motor Corp. set many company sales records. In the United States, Honda sold a record 1.6 million cars. In China, it sold 1 million cars in a year for the first time. Despite these record sales Honda’s profits were down sharply. Why? Huge rework costs associated with recalling millions of cars with defective airbags. By the end of 2015, Honda was forced to recall more than 25 million of its vehicles worldwide. Each of the vehicles had potentially defective airbags supplied by Takata Corporation. Airbag inflators use an explosive propellant similar to gunpowder to deploy airbags in the event of a crash. Because of defects in the manufacturing process, the propellant in millions of Takata inflators can degrade over time and explode at random. When that happens, the airbag’s metal housing can rupture, sending lethal shrapnel into the car. Ten deaths were linked to failed Takata airbags. With so many vehicles requiring rework, Honda’s recall costs soared. Honda spent $2.6 billion on recall-related expenses, including rework costs associated with replacing defective Takata airbags, compensation for Honda dealers, and legal expenses. Billions of dollars in future rework costs are anticipated, as well. As a result, Honda announced that it would no longer use Takata airbags for its new vehicles under development. Sergio Azenha/Alamy Stock Photo 1 718 Sources: Yoko Kubota, “Honda Motor Profit Slides on Recall Costs,” The Wall Street Journal (January 29, 2016); Yoko Kubota, “Honda Air-Bag Recall Costs Take a Toll,” The Wall Street Journal (November 4, 2015); Hiroku Tabuchi, “Honda Expands Recall of Takata Airbags as Its Longtime Partner’s Crisis Widens,” The New York Times (February 3, 2016). www.downloadslide.com For Honda, Takata, and other companies, the costs of producing defective output can be enormous. Accordingly, companies are increasingly focused on improving the quality of, and reducing defects in, their products, services, and activities. A rate of defects regarded as normal in the past is no longer tolerable, and companies strive for ongoing improvements in quality. Firms in industries as varied as construction (Skanska), aeronautics (Lockheed Martin), product development software (Dassault Systemes), and specialty food (Tate & Lyle) have set zero-defects goals. Reducing defects, and the waste associated with them, is also a key element of the sustainability programs now in place at many enlightened organizations and government bodies. In this chapter, we focus on three types of costs that arise as a result of defects—spoilage, rework, and scrap—and ways to account for them. We also describe how to determine (1) the cost of products, (2) cost of goods sold, and (3) inventory values when spoilage, rework, and scrap occur. Defining Spoilage, Rework, and Scrap The following terms used in this chapter may seem familiar to you, but be sure you understand them in the context of management accounting. Spoilage refers to units of production—whether fully or partially completed—that do not meet the specifications required by customers for good units and are discarded or sold at reduced prices. Some examples of spoilage are defective shirts, jeans, shoes, and carpeting sold as “seconds” and defective aluminum cans sold to aluminum manufacturers for remelting to produce other aluminum products. Rework refers to units of production that do not meet the specifications required by customers but that are subsequently repaired and sold as good finished units. For example, defective units of products (such as smartphones, tablets, and laptops) detected during or after the production process but before the units are shipped to customers can sometimes be reworked and sold as good products. Scrap is residual material that results from manufacturing a product. Examples are short lengths from woodworking operations, edges from plastic molding operations, and frayed cloth and end cuts from suit-making operations. Scrap can sometimes be sold for relatively small amounts. In that sense, scrap is similar to byproducts, which we studied in Chapter 16. The difference is that scrap arises as a residual from the manufacturing process and is not a product targeted for manufacture or sale by the firm. A certain amount of spoilage, rework, or scrap is inherent in many production processes. For example, semiconductor manufacturing is so complex and delicate that some spoiled units are inevitable due to dust adhering to wafers in the wafer production process and crystal defects in the silicon substrate. Usually, the spoiled units cannot be reworked. In the manufacture of high-precision machine tools, spoiled units can be reworked to meet standards, but only at a considerable cost. And in the mining industry, companies process ore that contains varying amounts of valuable metals and rock. Some amount of rock, which is scrap, is inevitable. Learning Objective 1 Understand the definitions of spoilage, . . . unacceptable units of production rework, . . . unacceptable units of production subsequently repaired and scrap . . . leftover material DecisiOn Point What are spoilage, rework, and scrap? Two Types of Spoilage Accounting for spoilage includes determining the magnitude of spoilage costs and distinguishing between the costs of normal and abnormal spoilage.2 To manage, control, and reduce spoilage costs, companies need to highlight them, not bury them as an unidentified part of the costs of good units manufactured. To illustrate normal and abnormal spoilage, consider Mendoza Plastics, which uses plastic injection molding to make casings for the iMac desktop computer. In January 2017, Mendoza incurs costs of $3,075,000 to produce 20,500 units. Of these 20,500 units, 20,000 are good units and 500 are spoiled units. Mendoza has no beginning inventory and no ending inventory that month. Of the 500 spoiled units, 400 units are spoiled because 2 The helpful suggestions of Samuel Laimon, University of Saskatchewan, are gratefully acknowledged. Learning Objective 2 Identify the differences between normal spoilage . . . spoilage inherent in an efficient production process and abnormal spoilage . . . spoilage that would not arise under efficient operation www.downloadslide.com 720 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap the injection molding machines are unable to manufacture good casings 100% of the time. That is, these units are spoiled even though the machines were run carefully and efficiently. The remaining 100 units are spoiled because of machine breakdowns and operator errors. Normal Spoilage Normal spoilage is spoilage inherent in a particular production process. In particular, it arises even when the process is carried out in an efficient manner. The costs of normal spoilage are typically included as a component of the costs of good units manufactured because good units cannot be made without also making some defective units. For this reason, normal spoilage costs are inventoried, that is, they are included in the cost of the good units completed. The following calculations show how Mendoza Plastics accounts for the cost of the 400 units’ normal spoilage: Manufacturing cost per unit, $3,075,000 , 20,500 units = $150 Manufacturing costs of good units alone, $150 per unit * 20,000 units Normal spoilage costs, $150 per unit * 400 units Manufacturing costs of good units completed (includes normal spoilage) $3,060,000 Manufacturing cost per good unit = = $153 20,000 units $3,000,000 60,000 $3,060,000 Normal spoilage rates are computed by dividing the units of normal spoilage by total good units completed, not total actual units started in production. At Mendoza Plastics, the normal spoilage rate is therefore computed as 400 , 20,000 = 2%. There is a tradeoff between the speed of production and the normal spoilage rate. Managers make a conscious decision about how many units to produce per hour with the understanding that, at the chosen rate, a certain level of spoilage is unavoidable. Abnormal Spoilage DecisiOn Point What is the distinction between normal and abnormal spoilage? Learning Objective 3 Account for spoilage in process costing using the weighted-average method . . . spoilage cost based on total costs and equivalent units completed to date and the first-in, first-out (FIFO) method . . . spoilage cost based on costs of current period and equivalent units of work done in current period Abnormal spoilage is spoilage that is not inherent in a particular production process and would not arise under efficient operating conditions. At Mendoza, the 100 units spoiled due to machine breakdowns and operator errors are abnormal spoilage. (If Mendoza had set 100% good units as its goal, then all 500 units of spoilage would be considered abnormal.) Abnormal spoilage is usually regarded as avoidable and controllable. Line operators and other plant personnel generally can decrease or eliminate abnormal spoilage by identifying the reasons for machine breakdowns, operator errors, and so forth, and by taking steps to prevent their recurrence. To highlight the effect of abnormal spoilage costs, companies calculate the units of abnormal spoilage and record the cost in the Loss from Abnormal Spoilage account, which appears as a separate line item in the income statement. That is, unlike normal spoilage, the costs of abnormal spoilage are not considered inventoriable and are written off as a period expense. At Mendoza, the loss from abnormal spoilage is $15,000 ($150 per unit * 100 units). Issues about accounting for spoilage arise in both process-costing and job-costing systems. We discuss both instances next, beginning with spoilage when process costing is used. Spoilage in Process Costing Using Weighted-Average and FIFO How do process-costing systems account for spoiled units? We have already said that units of abnormal spoilage should be counted and recorded separately in a Loss from Abnormal Spoilage account. But what about units of normal spoilage? The correct method is to count these units when computing both physical and equivalent output units in a process-costing system. The following example illustrates this approach. www.downloadslide.com Spoilage in proCeSS CoSting USing weighted-average and FiFo 721 Count All Spoilage Example 1: Chipmakers, Inc., manufactures computer chips for television sets. All direct materials are added at the beginning of the production process. To highlight issues that arise with normal spoilage, we assume there’s no beginning inventory and focus only on the direct materials costs. The following data are for May 2017. $ % Work in process, beginning inventory (May 1) Started during May Good units completed and transferred out during May Units spoiled (all normal spoilage) Work in process, ending inventory (May 31) Direct materials costs added in May Physical Units 0 10,000 5,000 1,000 4,000 & Direct Materials $270,000 Spoilage is detected upon completion of the process and has zero net disposal value. An inspection point is the stage of the production process at which products are examined to determine whether they are acceptable or unacceptable units. Spoilage is typically assumed to occur at the stage of completion where inspection takes place. As a result, the spoiled units in our example are assumed to be 100% complete for direct materials. Exhibit 18-1 calculates and assigns the cost of the direct materials used to produce both good units and units of normal spoilage. Overall, Chipmakers generated 10,000 equivalent units of output: 5,000 equivalent units in good units completed (5,000 physical units * 100%), 4,000 units in ending work in process (4,000 physical units * 100%), and 1,000 equivalent units in normal spoilage (1,000 physical units * 100%). Given total direct material costs of $270,000 in May, this yields an equivalent-unit cost of $27. The total cost of good units completed and transferred out, which includes the cost of normal spoilage, is then $162,000 exHibit 18-1 $ Costs to account for Divide by equivalent units of output Cost per equivalent unit of output Assignment of costs: Good units completed (5,000 units 3 $27 per unit) Add normal spoilage (1,000 units 3 $27 per unit) Total costs of good units completed and transferred out Work in process, ending (4,000 units 3 $27 per unit) Costs accounted for % Approach Counting Spoiled Units When Computing Output in Equivalent Units $270,000 410,000 $ 27 $ 135,000 27,000 162,000 108,000 $ 270,000 Using Equivalent Units to Account for the Direct Materials Costs of Good and Spoiled Units for Chipmakers, Inc., for May 2017 www.downloadslide.com 722 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap (6,000 equivalent units * $27). The ending work in process is assigned a cost of $108,000 (4,000 equivalent units * $27). Notice that the 4,000 units in ending work in process are not assigned any of the costs of normal spoilage because they have not yet been inspected. Undoubtedly some of the units in ending work in process will be found to be spoiled after they are completed and inspected in the next accounting period. At that time, their costs will be assigned to the good units completed in that period. Notice too that Exhibit 18-1 delineates the cost of normal spoilage as $27,000. By highlighting the magnitude of this cost, the approach helps to focus management’s attention on the potential economic benefits of reducing spoilage. Five-Step Procedure for Process Costing with Spoilage Example 2: Anzio Company manufactures a recycling container in its forming department. Direct materials are added at the beginning of the production process. Conversion costs are added evenly during the production process. Some units of this product are spoiled as a result of defects, which are detectable only upon inspection of finished units. Normally, spoiled units are 10% of the finished output of good units. That is, for every 10 good units produced, there is 1 unit of normal spoilage. Summary data for July 2017 are as follows: $ Work in process, beginning inventory (July 1) Degree of completion of beginning work in process Started during July Good units completed and transferred out during July Work in process, ending inventory (July 31) Degree of completion of ending work in process Total costs added during July Normal spoilage as a percentage of good units Degree of completion of normal spoilage Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage % & Physical Units (1) 1,500 Direct Materials (2) $12,000 100% ' ( Conversion Total Costs Costs (3) (4) 5 (2) 1 (3) $ 21,000 $ 9,000 60% 8,500 7,000 2,000 100% $76,500 50% $89,100 100% 100% 100% 100% $165,600 10% We can slightly modify the five-step procedure for process costing used in Chapter 17 to include the costs of Anzio Company’s spoilage. Step 1: Summarize the Flow of Physical Units of Output. Identify the number of units of both normal and abnormal spoilage. Good units Total Units in beginning Units Units in ending = a + b - ° completed and + ¢ Spoilage work@in@process inventory started work@in@process inventory transferred out = (1,500 + 8,500) - (7,000 + 2,000) = 10,000 - 9,000 = 1,000 units www.downloadslide.com Spoilage in proCeSS CoSting USing weighted-average and FiFo Recall that Anzio Company’s normal spoilage is 10% of good output. So, the number of units of normal spoilage equals 10% of the 7,000 units of good output, or 700 units. With this information, we can then calculate the number of units of abnormal spoilage: Abnormal spoilage = Total spoilage - Normal spoilage = 1,000 units - 700 units = 300 units Step 2: Compute the Output in Terms of Equivalent Units. Managers compute the equivalent units for spoilage the same way they compute equivalent units for good units. All spoiled units are included in the computation of output units. Because Anzio’s inspection point is at the completion of production, the same amount of work will have been done on each spoiled and each completed good unit. Step 3: Summarize the Total Costs to Account For. The total costs to account for are all the costs debited to Work in Process. The details for this step are similar to Step 3 in Chapter 17. Step 4: Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit. This step is similar to Step 4 in Chapter 17. Step 5: Assign Costs to the Units Completed, Spoiled Units, and Units in Ending Workin-Process Inventory. This step now includes computing of the cost of spoiled units as well as the cost of good units. We illustrate these five steps of process costing for the weighted-average and FIFO methods next. The standard-costing method is illustrated in the appendix to this chapter. Weighted-Average Method and Spoilage Exhibit 18-2, Panel A, presents Steps 1 and 2 to calculate the equivalent units of work done to date and includes calculations of equivalent units of normal and abnormal spoilage. Exhibit 18-2, Panel B, presents Steps 3, 4, and 5 (together called the production-cost worksheet). In Step 3, managers summarize the total costs to account for. In Step 4, they calculate the cost per equivalent unit using the weighted-average method. Note how, for each cost category, the costs of beginning work in process and the costs of work done in the current period are totaled and divided by equivalent units of all work done to date to calculate the weightedaverage cost per equivalent unit. In the final step, managers assign the total costs to completed units, normal and abnormal spoiled units, and ending inventory by multiplying the equivalent units calculated in Step 2 by the cost per equivalent unit calculated in Step 4. Also note that the $13,825 costs of normal spoilage are added to the costs of the good units completed and transferred out. Cost per good unit Total costs transferred out (including normal spoilage) completed and transferred = Number of good units produced out of the process = $152,075 , 7,000 good units = $21.725 per good unit This amount is not equal to $19.75 per good unit, the sum of the $8.85 cost per equivalent unit of direct materials plus the $10.90 cost per equivalent unit of conversion costs. That’s because the cost per good unit equals the sum of the direct materials and conversion costs per equivalent unit, which is $19.75, plus a share of normal spoilage, $1.975 ($13,825 , 7,000 good units), for a total of $21.725 per good unit. The $5,925 costs of abnormal spoilage are charged to the Loss from Abnormal Spoilage account and do not appear in the costs of good units.3 3 The actual costs of spoilage (and rework) are often greater than the costs recorded in the accounting system because the opportunity costs of disruption of the production line, storage, and lost contribution margins are not recorded in accounting systems. Chapter 19 discusses these opportunity costs from the perspective of cost management. 723 www.downloadslide.com 724 Chapter 18 exHibit 18-2 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap Weighted-Average Method of Process Costing with Spoilage for the Forming Department for July 2017 PANEL A: Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units $ % & (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning (given, p. 722) Started during current period (given, p. 722) To account for Good units completed and transferred out during current period b c Work in process, ending (given, p. 722) (2,000 3 100%; 2,000 3 50%) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done to date 7,000 700 700 300 300 2,000 1,000 10,000 9,000 2,000 10,000 a Normal spoilage is 10% of good units transferred out; 10% 3 7,000 5 700 units. Degree of completion of normal spoilage in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 100%. b Abnormal spoilage 5 Total spoilage ] Normal spoilage 5 1,000 ] 700 5 300 units. Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 100%. 7,000 300 Abnormal Spoilage (300 3 100%; 300 3 100%) 7,000 700 Normal Spoilage (700 3 100%; 700 3 100%) ( (Step 2) Equivalent Units Conversion Direct Costs Materials 10,000 a Physical Units 1,500 8,500 ' c Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. PANEL B: Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed, Spoiled Units, and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory (Step 3) (Step 4) (Step 5) Work in process, beginning (given, p. 722) Costs added in current period (given, p. 722) Total costs to account for Costs incurred to date Divide by equivalent units of work done to date (Panel A) Cost per equivalent unit Assignment of costs: Good units completed and transferred out (7,000 units): Costs before adding normal spoilage Total Production Costs $ 21,000 165,600 $186,600 $88,500 410,000 $ 8.85 (A) (B) Work in process, ending (2,000 units) (C) (A) 1 (B) 1 (C) Total costs accounted for d $98,100 4 9,000 $ 10.90 (7,000d 3 $8.85) 1 (7,000d3 $10.90) 13,825 152,075 5,925 (700d 3 $8.85) 1 (700d 3 $10.90) 28,600 $186,600 1 1 1 Conversion Costs $ 9,000 89,100 $98,100 $138,250 Normal spoilage (700 units) Total costs of good units completed and transferred out Abnormal spoilage (300 units) Direct Materials $12,000 76,500 $88,500 Equivalent units of direct materials and conversion costs calculated in Step 2 in Panel A. d (300d 3 $8.85) 1 (300 3 $10.90) d (2,000 3 $8.85) 1 (1,000d3 $10.90) $88,500 $98,100 1 www.downloadslide.com Spoilage in proCeSS CoSting USing weighted-average and FiFo exHibit 18-3 725 First-In, First-Out (FIFO) Method of Process Costing with Spoilage for the Forming Department for July 2017 PANEL A: Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units $ % & ' (Step 1) Flow of Production Physical Units 1,500 8,500 Work in process, beginning (given, p. 722) Started during current period (given, p. 722) 10,000 To account for Good units completed and transferred out during current period From beginning work in process a [1,500 3 (100% – 100%); 1,500 3 (100% – 60%)] Started and completed (5,500 3 100%; 5,500 3 100%) 1,500 700 Abnormal Spoilaged (300 3 100%; 300 3 100%) 300 Accounted for Equivalent units of work in current period 0 600 5,500 5,500 700 700 300 300 2,000 1,000 8,500 8,100 5,500b Normal Spoilagec (700 3 100%; 700 3 100%) Work in process, ending e (given, p. 722) (2,000 3 100%; 2,000 3 50%) ( (Step 2) Equivalent Units Direct Materials Conversion Costs 2,000 10,000 a Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 60%. b 7,000 physical units completed and transferred out minus 1,500 physical units completed and transferred out from beginning work-in-process inventory. c Normal spoilage is 10% of good units transferred out; 10% 3 7,000 5 700 units. Degree of completion of normal spoilage in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 100%. Abnormal spoilage 5 Total spoilage – Normal spoilage 5 1,000 – 700 5 300 units. Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs,100%. e Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. d PANEL B: Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed, Spoiled Units, and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory Total Production Costs Direct Materials $ 21,000 165,600 $186,600 $ 12,000 76,500 $88,500 Conversion Costs Work in proc ess, beginning (given, p. 722) Costs added in current period (given, p. 722) Total costs to account for Costs added in current period Divide by equivalent units of work done in current period (Panel A) Cost per equivalent unit Assignment of costs: Good units completed and transferred out (7,000 units): Work in process, beginning (1,500 units) Costs added to beginning work in process in current period Total from beginning inventory before normal spoilage Started and completed before normal spoilage (5,500 units) Normal spoilage (700 units) (A) (B) (C) Total costs of good units completed and transferred out Abnormal spoilage (300 units) Work in process, ending (2,000 units) (Step 3) (Step 4) (Step 5) (A) 1 (B) 1 (C) Total costs accounted for fEquivalent units of direct materials and conversion costs calculated in Step 2 in Panel A. 1 1 1 $76,500 48,500 $ 9 $ 21,000 6,600 27,600 110,000 14 ,000 $ 9,000 89,100 $ 98,100 $ 89,100 4 8,100 $ 11 $9,000 $12,000 (0 f 3 $9) 1 (600 f 3 $11) (5,500f 3 $9) 1 (5,500f 3 $11) (700 3 $9) 1 (700f 3 $11) (300f 3 $9) 1 (300f 3 $11) f 151,600 6,000 29,000 (2,000 3 $9) 1 (1,000f 3 $11) $186,600 $88,500 1 $98,100 f www.downloadslide.com 726 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap trY it! Azure Textiles Company makes silk banners and uses the weighted-average method 18-1 of process costing. Direct materials are added at the beginning of the process, and conversion costs are added evenly during the process. Spoilage is detected upon inspection at the completion of the process. Spoiled units are disposed of at zero net disposal value. Work in process, July 1a Started in July 2017 Good units completed and transferred out in July Normal spoilage Abnormal spoilage Work in process, July 31b Total costs added during July 2017 Physical Units (Banners) 1,000 ? 9,000 100 50 2,000 Direct Materials $ 1,423 Conversion Costs $ 1,110 $12,180 $27,750 a Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 30%. b Determine the equivalent units of work done in July, and calculate the cost of units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), the cost of abnormal spoilage, and the cost of units in ending inventory. FIFO Method and Spoilage Exhibit 18-3, Panel A, presents Steps 1 and 2 using the FIFO method, which focuses on equivalent units of work done in the current period. Exhibit 18-3, Panel B, presents Steps 3, 4, and 5. Note how when assigning costs, the FIFO method keeps the costs of the beginning work in process separate and distinct from the costs of the work done in the current period. All spoilage costs are assumed to be related to units completed during the period, using the unit costs of the current period.4 trY it! 18-2 Consider Azure Textiles Company again. With the same information for July 2017 as provided in Try It 18-1, redo the problem assuming Azure uses FIFO costing instead. Chapter 17 highlighted taxes, performance evaluation, and accounting-based covenants as some of the elements managers must take into account when choosing between the FIFO and weighted-average methods. It also stressed the importance of making careful estimates of degrees of completion in order to avoid misstating operating income. All of these considerations apply equally well to the material in this chapter. In addition, a new issue that arises with spoilage is that of estimating the normal spoilage percentage in an unbiased manner. A supervisor who wishes to show better performance might categorize more of the spoilage as normal, thereby reducing the amount that must be written off against income as the loss from abnormal spoilage. Managers must stress the value of consistent and unbiased estimates of completion and normal spoilage percentages and drive home the importance of pursuing ethical actions and reporting the correct income figures, regardless of the short-term consequences of doing so. 4 To simplify calculations under FIFO, spoiled units are accounted for as if they were started in the current period. Although some of the beginning work in process probably did spoil, all spoilage is treated as if it came from current production. www.downloadslide.com inSpeCtion pointS and alloCating CoStS oF normal Spoilage 727 Journal Entries The information from Panel B in Exhibits 18-2 and 18-3 supports the following journal entries to transfer good units completed to finished goods and to recognize the loss from abnormal spoilage. Finished Goods Work in Process—Forming To record the transfer of good units completed in July. Loss from Abnormal Spoilage Work in Process—Forming To record the abnormal spoilage detected in July. Weighted-Average 152,075 152,075 DecisiOn Point FIFO 151,600 5,925 151,600 6,000 5,925 6,000 How do the weightedaverage and FIFO methods of process costing calculate the costs of good units and spoilage? Inspection Points and Allocating Costs of Normal Spoilage Spoilage might occur at various stages of a production process, but it is typically detected only at one or more inspection points. The cost of spoiled units equals all costs incurred in producing them up to the point of inspection. When spoiled goods have a disposal value (for example, carpeting sold as “seconds”), we compute a net cost of the spoilage by deducting the disposal value from the costs of the spoiled goods. The unit costs of normal and abnormal spoilage are the same when the two are detected at the same inspection point. This is the case in our Anzio Company example, where inspection occurs only upon completion of the units. However, situations may arise when abnormal spoilage is detected at a different point than normal spoilage. Consider shirt manufacturing. Normal spoilage in the form of defective shirts is identified upon inspection at the end of the production process. Now suppose a faulty machine causes many defective shirts to be produced at the halfway point of the production process. These defective shirts are abnormal spoilage and occur at a different point in the production process than normal spoilage. Then the per-unit cost of the abnormal spoilage, which is based on costs incurred up to the halfway point of the production process, differs from the per-unit cost of normal spoilage, which is based on costs incurred through the end of the production process. The costs of abnormal spoilage are separately accounted for as losses of the accounting period in which they are detected. However, recall that normal spoilage costs are added to the costs of good units, which raises an additional issue: Should normal spoilage costs be allocated between completed units and ending work-in-process inventory? The common approach is to presume that normal spoilage occurs at the inspection point in the production cycle and to allocate its cost over all units that have passed that point during the accounting period. Anzio Company inspects units only at the end of the production process. So, the units in ending work-in-process inventory are not assigned any costs of normal spoilage. Suppose Anzio were to inspect units at an earlier stage. Then, if the units in ending work in process have passed the inspection point, the costs of normal spoilage would be allocated to units in ending work in process as well as to completed units. For example, if the inspection point is at the halfway point of production, then any ending work in process that is at least 50% complete would be allocated a full measure of the normal spoilage costs, and those spoilage costs would be calculated on the basis of all costs incurred up to the inspection point. However, if the ending work-in-process inventory is less than 50% complete, no normal spoilage costs would be allocated to it. To better understand these issues, assume Anzio Company inspects units at various stages in the production process. How does this affect the amount of normal and abnormal spoilage? As before, consider the forming department, and recall that direct materials are added at the start of production, whereas conversion costs are added evenly during the process. Consider three different cases: Inspection occurs at (1) the 20%, (2) the 55%, or (3) the 100% completion stage. The last option is the one we have analyzed so far. Assume that Learning Objective 4 Account for spoilage at various stages of completion in process costing . . . spoilage costs vary based on the point at which inspection is carried out www.downloadslide.com 728 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap normal spoilage is 10% of the good units passing inspection. A total of 1,000 units are spoiled in all three cases. Normal spoilage is computed on the basis of the number of good units that pass the inspection point during the current period. The following data are for July 2017. Note how the number of units of normal and abnormal spoilage changes depending on when inspection occurs. % $ & ' Physical Units: Stage of Completion at Which Inspection Occurs 20% 55% 100% 1,500 1,500 1,500 8,500 8,500 8,500 10,000 10,000 10,000 Flow of Production Work in process, beginninga Started during July To account for Good units completed and transferred out (10,000 ] 1,000 spoiled ] 2,000 ending) Normal Spoilage Abnormal Spoilage (1,000 ] normal spoilage) Work in process, endingb Accounted for 7,000 750c 250 2,000 10,000 7,000 550d 450 2,000 10,000 7,000 700e 300 2,000 10,000 a b Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 60%. Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. c 10% 3 (8,500 units started ] 1,000 units spoiled), because only the units started passed the 20% completion inspection point in the current period. Beginning work in process is excluded from this calculation because, being 60% complete at the start of the period, it passed the inspection point in the previous period. d 10% 3 (8,500 units started ] 1,000 units spoiled ] 2,000 units in ending work in process). Both beginning and ending work in process are excluded since neither was inspected this period. e 10% 3 7,000, because 7,000 units are fully completed and inspected in the current period. The following diagram shows the flow of physical units for July and illustrates the normal spoilage numbers in the table. Note that 7,000 good units are completed and transferred out—1,500 from beginning work in process and 5,500 started and completed during the period—while 2,000 units are in ending work in process. 0% 20% 50% 55% 60% 100% 1,500 units from beginning work in process 5,500 units started and completed Work done on 2,000 units in ending work in process To see the number of units passing each inspection point, consider in the diagram the vertical lines at the 20%, 55%, and 100% inspection points. Note that the vertical line at 20% crosses two horizontal lines—5,500 good units started and completed and 2,000 units in ending work in process—for a total of 7,500 good units. (The 20% vertical line does not cross the line representing work done on the 1,500 good units completed from beginning work in process because these units are already 60% complete at the start of the period and, hence, are not inspected this period.) Normal spoilage equals 10% of www.downloadslide.com inSpeCtion pointS and alloCating CoStS oF normal Spoilage 7,500 = 750 units. On the other hand, the vertical line at the 55% point crosses just the second horizontal line, indicating that only 5,500 good units pass this point. Normal spoilage in this case is 10% of 5,500 = 550 units. At the 100% point, the normal spoilage is 10% of 7,000 (1,500 + 5,500) good units = 700 units. Exhibit 18-4 shows how equivalent units are computed under the weighted-average method if units are inspected at the 20% completion stage. The calculations depend on the direct materials and conversion costs incurred to get the units to this inspection point. The spoiled units have 100% of their direct materials costs and 20% of their conversion costs. Because the ending work-in-process inventory has passed the inspection point, these units are assigned the normal spoilage costs, just like the units that have been completed and transferred out. For example, the conversion costs of units completed and transferred out include the conversion costs for 7,000 good units produced plus 20% * (10% * 5,500) = 110 equivalent units of normal spoilage. We multiply by 20% to obtain the equivalent units of normal spoilage because the conversion costs are only 20% complete at the inspection point. The conversion costs of the ending work-in-process inventory include the conversion costs of 50% of 2,000 = 1,000 equivalent good units plus 20% * (10% * 2,000) = 40 equivalent units of normal spoilage. Thus, the equivalent units of normal spoilage accounted for are 110 equivalent units related to the units completed and transferred out plus 40 equivalent units related to the units in ending work in process, for a total of 150 equivalent units, as Exhibit 18-4 shows. Early inspections can help prevent any further costs being wasted on units that are already spoiled. For example, suppose the units can be inspected when they are 70% complete rather than 100% complete. If the spoilage occurs prior to the 70% point, a company can avoid incurring the final 30% of conversion costs on the spoiled units. While not applicable in the Anzio example, more generally a company can also save on the packaging or other direct materials that are added after the 70% stage. The downside to conducting inspections at too early a stage is that units spoiled at later stages of the process may go undetected. It is for these reasons that firms often conduct multiple inspections and also empower workers to identify and resolve defects on a timely basis. 729 DecisiOn Point How does inspection at various stages of completion affect the amount of normal and abnormal spoilage? exHibit 18-4 $ % (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in process, beginning a Started during current period To account for Good units completed and transferred out Normal Spoilage (750 3 100%; 750 3 20%) Abnormal Spoilage (250 3 100%; 250 3 20%) Work in process, endingb (2,000 3 100%; 2,000 3 50%) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done to date Physical Units 1,500 8,500 10,000 7,000 750 & (Step 2) Equivalent Units Direct Conversion Materials Costs 7,000 7,000 750 150 250 50 2,000 1,000 10,000 8,200 250 2,000 10,000 a b ' Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 60%. Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. Computing Equivalent Units with Spoilage Using the Weighted-Average Method of Process Costing with Inspection at 20% of Completion for the Forming Department for July 2017 www.downloadslide.com 730 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap Normal spoilage is 6% of the good units passing inspection in a forging process. In 18-3 March, a total of 10,000 units were spoiled. Other data include units started during March, 120,000; work in process, beginning, 14,000 units (20% completed for conversion costs); and work in process, ending, 11,000 units (70% completed for conversion costs). trY it! Compute the normal and abnormal spoilage in units, assuming the inspection point is at (a) the 15% stage of completion, (b) the 40% stage of completion, and (c) the 100% stage of completion. Job Costing and Spoilage Learning Objective 5 Account for spoilage in job costing . . . normal spoilage assigned directly or indirectly to job; abnormal spoilage written off as a loss of the period The concepts of normal and abnormal spoilage also apply to job-costing systems. Companies attempt to identify abnormal spoilage separately so they can work to eliminate it altogether. The costs of abnormal spoilage are not considered to be inventoriable costs and are written off as costs of the accounting period in which the abnormal spoilage is detected. Normal spoilage costs in job-costing systems—as in process-costing systems—are inventoriable costs, although increasingly companies are tolerating only small amounts of spoilage as normal. When assigning costs, job-costing systems generally distinguish normal spoilage attributable to a specific job from normal spoilage common to all jobs. We describe accounting for spoilage in job costing using the following example. Example 3: In the Hull Machine Shop, 5 aircraft parts out of a job lot of 50 aircraft parts are spoiled. The costs assigned prior to the inspection point are $2,000 per part. When the spoilage is detected, the spoiled goods are inventoried at $600 per part, the net disposal value. Our presentation here and in subsequent sections focuses on how the $2,000 cost per part is accounted for. Normal Spoilage Attributable to a Specific Job When normal spoilage occurs because of the specifications of a particular job, that job bears the cost of the spoilage minus the disposal value of the spoilage. The journal entry to recognize the disposal value is as follows (items in parentheses indicate subsidiary ledger postings): Materials Control (spoiled goods at current net disposal value): 5 units * $600 per unit Work-in-Process Control (specific job): 5 units * $600 per unit 3,000 3,000 Note that the Work-in-Process Control (for the specific job) has already been debited (charged) $10,000 for the spoiled parts (5 spoiled parts * $2,000 per part). So, the net cost of the normal spoilage is $7,000 ($10,000 - $3,000), which is an additional cost of the 45 (50 - 5) good units produced. Therefore, total cost of the 45 good units is $97,000: $90,000 (45 units * $2,000 per unit) incurred to produce the good units plus the $7,000 net cost of normal spoilage. Cost per good unit is $2,155.56 ($97,000 , 45 good units). Normal Spoilage Common to All Jobs In some cases, spoilage may be considered a normal characteristic of the production process. The spoilage inherent in production will, of course, occur when a specific job is being worked on. However, the spoilage is not attributable to, and hence is not charged directly to, the specific job. Instead, the spoilage is allocated indirectly to the job as manufacturing overhead because the spoilage is common to all jobs. The journal entry is as follows: Materials Control (spoiled goods at current disposal value): 5 units * $600 per unit Manufacturing Overhead Control (normal spoilage): ($10,000 - $3,000) Work-in-Process Control (specific job): 5 units * $2,000 per unit 3,000 7,000 10,000 www.downloadslide.com Job CoSting and rework 731 When normal spoilage is common to all jobs, the budgeted manufacturing overhead rate includes a provision for the normal spoilage cost. The normal spoilage cost is spread, through overhead allocation, over all jobs rather than being allocated to a specific job.5 For example, if Hull produced 140 good units from all jobs in a given month, the $7,000 of normal spoilage overhead costs would be allocated at the rate of $50 per good unit ($7,000 , 140 good units). Normal spoilage overhead costs allocated to the 45 good units in the current job would be $2,250 ($50 * 45 good units). The total cost of the 45 good units is $92,250: $90,000 (45 units * $2,000 per unit) incurred to produce the good units plus $2,250 of normal spoilage overhead costs. The cost per good unit is $2,050 ($92,250 , 45 good units). Abnormal Spoilage If the spoilage is abnormal, the net loss is charged to the Loss from Abnormal Spoilage account. Unlike normal spoilage costs, abnormal spoilage costs are not included as a part of the cost of good units produced. The total cost of the 45 good units is $90,000 (45 units * $2,000 per unit). The cost per good unit is $2,000 ($90,000 , 45 good units). Materials Control (spoiled goods at current disposal value): 5 units * $600 per unit Loss from Abnormal Spoilage ($10,000 - $3,000) Work-in-Process Control (specific job): 5 units * $2,000 per unit 3,000 7,000 10,000 Even though, for external reporting purposes, abnormal spoilage costs are written off in the accounting period and are not linked to specific jobs or units, companies often identify the particular reasons for the abnormal spoilage and, when appropriate, link it with specific jobs or units for cost management purposes. The accounting treatment described above highlights the potential impact of misclassifying the nature of the spoilage. Normal spoilage costs are inventoriable and are added to the cost of good units produced, while abnormal spoilage costs are expensed in the accounting period in which they occur. So, when inventories are present, classifying spoilage as normal rather than abnormal results in an increase in current operating income. In the above example, if the 45 parts remain unsold at the end of the period, such misclassification would boost income for that period by $7,000. As with our discussion of completion percentages, it is important for managers to verify that spoilage rates and spoilage categories are not manipulated by department supervisors for short-term benefits. DecisiOn Point How do job-costing systems account for spoilage? Job Costing and Rework Rework refers to units of production that are inspected, determined to be unacceptable, repaired, and sold as acceptable finished goods. We again distinguish (1) normal rework attributable to a specific job, (2) normal rework common to all jobs, and (3) abnormal rework. Consider the Hull Machine Shop data in Example 3 on page 730. Assume the five spoiled parts are reworked. The journal entry for the $10,000 of total costs (the details of these costs are assumed) assigned to the five spoiled units before considering rework costs is as follows: Work-in-Process Control (specific job) Materials Control Wages Payable Control Manufacturing Overhead Allocated 10,000 4,000 4,000 2,000 Assume the rework costs equal $3,800 ($800 in direct materials, $2,000 in direct manufacturing labor, and $1,000 in manufacturing overhead). 5 Note that costs already assigned to products are charged back to Manufacturing Overhead Control, which generally accumulates only costs incurred, not both costs incurred and costs already assigned. Learning Objective 6 Account for rework in job costing . . . normal rework assigned directly or indirectly to job; abnormal rework written off as a loss of the period www.downloadslide.com 732 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap Normal Rework Attributable to a Specific Job If the rework is normal but occurs because of the requirements of a specific job, the rework costs are charged to that job. The journal entry is as follows: Work-in-Process Control (specific job) Materials Control Wages Payable Control Manufacturing Overhead Allocated 3,800 800 2,000 1,000 Normal Rework Common to All Jobs The costs of the rework when it is normal and not attributable to a specific job are charged to manufacturing overhead and are spread, through overhead allocation, over all jobs. Manufacturing Overhead Control (rework costs) Materials Control Wages Payable Control Manufacturing Overhead Allocated 3,800 800 2,000 1,000 Abnormal Rework If the rework is abnormal, it is charged to a loss account. Loss from Abnormal Rework Materials Control Wages Payable Control Manufacturing Overhead Allocated DecisiOn Point How do job-costing systems account for rework? trY it! 3,800 800 2,000 1,000 Accounting for rework in a process-costing system also requires abnormal rework to be distinguished from normal rework. Process costing accounts for abnormal rework in the same way as job costing. Accounting for normal rework follows the accounting described for normal rework common to all jobs (units) because masses of identical or similar units are being manufactured. Costing rework focuses managers’ attention on the resources wasted on activities that would not have to be undertaken if the product had been made correctly. The cost of rework prompts managers to seek ways to reduce rework, for example, by designing new products or processes, training workers, or investing in new machines. To eliminate rework and to simplify the accounting, some companies set a standard of zero rework. All rework is then treated as abnormal and is written off as a cost of the current period. Avid Corporation manufactures a sophisticated controller that is compatible with a 18-4 variety of gaming consoles. Excluding rework costs, the cost of manufacturing one controller is $220. This consists of $120 in direct materials, $24 in direct manufacturing labor, and $76 in manufacturing overhead. Maintaining a reputation for quality is critical to Avid. Any defective units identified at the inspection point are sent back for rework. It costs Avid $72 to rework each defective controller, including $24 in direct materials, $18 in direct manufacturing labor, and $30 in manufacturing overhead. In August 2017, Avid manufactured 1,000 controllers, 80 of which required rework. Of these 80 controllers, 50 were considered normal rework common to all jobs and the other 30 were considered abnormal rework. a. Prepare journal entries to record the accounting for both the normal and abnormal rework. b. What were the total rework costs of controllers in August 2017? c. Suppose instead that the normal rework is attributable entirely to Job #9, for 200 controllers intended for Australia. In this case, what are the total and unit costs of the good units produced for that job in August 2017? Prepare journal entries for the manufacture of the 200 controllers, as well as the normal rework costs. www.downloadslide.com aCCoUnting For SCrap 733 Accounting for Scrap Scrap is residual material that results from manufacturing a product; it has low total sales value compared with the total sales value of the product. No distinction is made between normal and abnormal scrap because no cost is assigned to scrap. The only distinction made is between scrap attributable to a specific job and scrap common to all jobs. There are two aspects of accounting for scrap: 1. Planning and control, including physical tracking 2. Inventory costing, including when and how scrap affects operating income Initial entries to scrap records are commonly expressed in physical terms. In various industries, companies quantify items such as stamped-out metal sheets or edges of molded plastic parts by weighing, counting, or some other measure. Scrap records not only help measure efficiency, but also help keep track of scrap, and so reduce the chances of theft. Companies use scrap records to prepare periodic summaries of the amounts of actual scrap compared with budgeted or standard amounts. Scrap is either sold or disposed of quickly or it is stored for later sale, disposal, or reuse. To carefully track their scrap, many companies maintain a distinct account for scrap costs somewhere in their accounting system. The issues here are similar to the issues in Chapter 16 regarding the accounting for byproducts: ■ ■ When should the value of scrap be recognized in the accounting records—at the time scrap is produced or at the time scrap is sold? How should the revenues from scrap be accounted for? To illustrate, we extend our Hull example. Assume the manufacture of aircraft parts generates scrap and that the scrap from a job has a net sales value of $900. Recognizing Scrap at the Time of Its Sale When the dollar amount of the scrap is immaterial, it is simplest to record the physical quantity of scrap returned to the storeroom and to regard the revenues from the sale of scrap as a separate line item in the income statement. The only journal entry is as follows: Sale of scrap: Cash or Accounts Receivable Scrap Revenues 900 900 When the dollar amount of the scrap is material and it is sold quickly after it is produced, the accounting depends on whether the scrap is attributable to a specific job or is common to all jobs. Scrap Attributable to a Specific Job Job-costing systems sometimes trace scrap revenues to the jobs that yielded the scrap. This method is used only when the tracing can be done in an economically feasible way. For example, the Hull Machine Shop and its customers, such as the U.S. Department of Defense, may reach an agreement that provides for charging specific jobs with all rework or spoilage costs and then crediting these jobs with all scrap revenues that arise from the jobs. The journal entry is as follows: Scrap returned to storeroom: Sale of scrap: No journal entry. [Notation of quantity received and related job entered in the inventory record] Cash or Accounts Receivable Work-in-Process Control Posting made to specific job cost record. 900 900 Learning Objective 7 Account for scrap . . . reduces cost of job either at time of sale or at time of production www.downloadslide.com 734 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap Unlike spoilage and rework, there is no cost assigned to the scrap, so no distinction is made between normal and abnormal scrap. All scrap revenues, whatever the amount, are credited to the specific job. Scrap revenues reduce the costs of the job. Scrap Common to All Jobs The journal entry in this case is as follows: Scrap returned to storeroom: Sale of scrap: No journal entry. [Notation of quantity received and related job entered in the inventory record] Cash or Accounts Receivable 900 Manufacturing Overhead Control 900 Posting made to subsidiary ledger—“Sales of Scrap” column on department cost record. Because the scrap is not linked with any particular job or product, all products bear its costs without any credit for scrap revenues except in an indirect manner: The expected scrap revenues are considered when setting the budgeted manufacturing overhead rate. Thus, the budgeted overhead rate is lower than it would be otherwise. This method of accounting for scrap is also used in process costing when the dollar amount of scrap is immaterial because the scrap in process costing is common to the manufacture of all the identical or similar units produced (and cannot be identified with specific units). Recognizing Scrap at the Time of Its Production Our preceding illustrations assume that scrap returned to the storeroom is sold quickly, so it is not assigned an inventory cost figure. Sometimes, as in the case with edges of molded plastic parts, the value of the scrap is not immaterial, and the time between storing it and selling or reusing it can be long and unpredictable. In these situations, the company assigns an inventory cost to scrap at a conservative estimate of its net realizable value so that production costs and related scrap revenues are recognized in the same accounting period. Some companies tend to delay selling scrap until its market price is attractive. Volatile price fluctuations are typical for scrap metal. In these cases, it’s not easy to determine a “reasonable inventory value.” Scrap Attributable to a Specific Job The journal entry in the Hull example is as follows: Scrap returned to storeroom: Materials Control Work-in-Process Control 900 900 Scrap Common to All Jobs The journal entry in this case is as follows: Scrap returned to storeroom: Materials Control Manufacturing Overhead Control 900 900 Notice that the Materials Control account is debited in place of Cash or Accounts Receivable. When the scrap is sold, the journal entry is as follows: Sale of scrap: Cash or Accounts Receivable Materials Control 900 900 www.downloadslide.com aCCoUnting For SCrap cOncepts in actiOn 735 Nestlé’s Journey to Zero Waste for Disposal Almost one third of global food production is either wasted or lost every year. Food waste not only generates excess greenhouse gas emissions and wastes water, but it also negatively affects farmer income and the availability and cost of food worldwide. Many food and beverage companies around the world are addressing this growing problem. In 2015, Nestlé pledged that all of its production sites worldwide would generate zero waste for disposal by 2020. That is, no waste will go to a landfill or be incinerated without energy being recovered from the process beforehand. As part of this process, Nestlé is focused on reusing scraps and Bob Pardue—Signs/Alamy Stock Photo byproducts created during its food manufacturing processes. The company already recovers 91% of the materials that arise from manufacturing. Examples of recovery that increase sustainability include the following: ■ Composting: Nestlé’s Shimada factory in Japan recycles some of the coffee grounds produced during the coffee manufacturing process by fermenting them and turning them into soil, which is donated to local parks and schools. ■ Incineration with energy recovery: In 22 Nescafé factories, Nestlé uses the spent coffee grounds resulting from the manufacturing process as a source of renewable energy. ■ Animal feed: Also in Japan, Nestlé’s zero waste KitKat factory in Kasumigaura turns all its food waste into animal feed, sending it to local farms. With 468 factories in 86 countries, Nestlé’s zero waste for disposal pledge will require a significant effort to avoid food waste and improve efficiency throughout its supply chain. That said, the company has already reduced its total waste for disposal by 62% since 2005 and is committed to further improvement. Sources: Nestlé SA, “Waste and recovery” (http://www.nestle.com/csv/environmental-sustainability/product-life-cycle/waste-and-recovery), accessed April 2016; “Nestlé pledges to reduce food loss and waste,” Nestlé SA press release, Vevey, Switzerland, May 12, 2015 (http://www.nestle.com/media/ news/nestle-pledges-to-reduce-food-loss-and-waste). Scrap is sometimes reused as direct material rather than sold as scrap. In this case, Materials Control is debited at its estimated net realizable value and then credited when the scrap is reused. For example, the entries when the scrap is common to all jobs are as follows: Scrap returned to storeroom: Reuse of scrap: Materials Control Manufacturing Overhead Control Work-in-Process Control Materials Control 900 900 900 900 Accounting for scrap under process costing is similar to accounting under job costing when scrap is common to all jobs. That’s because the scrap in process costing is common to the manufacture of masses of identical or similar units. Managers focus their attention on ways to reduce scrap and to use it more profitably, especially when the cost of scrap is high. For example, General Motors has redesigned its plastic injection molding processes to reduce the scrap plastic that must be broken away from its molded products. General Motors also regrinds and reuses the plastic scrap as direct material, saving substantial input costs. Concepts in Action: Nestlé’s Journey to Zero Waste for Disposal shows how a firm that is deeply committed to principles of environmental sustainability minimizes the waste and scrap from its processes. DecisiOn Point How is scrap accounted for? www.downloadslide.com 736 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap Problem for Self-StudY Burlington Textiles has some spoiled goods that had an assigned cost of $40,000 and zero net disposal value. Prepare a journal entry for each of the following conditions under (a) process costing (department A) and (b) job costing: Required 1. Abnormal spoilage of $40,000 2. Normal spoilage of $40,000 regarded as common to all operations 3. Normal spoilage of $40,000 regarded as attributable to specifications of a particular job Solution (a) Process Costing 1. Loss from Abnormal Spoilage Work in Process—Dept. A 40,000 (b) Job Costing Loss from Abnormal Spoilage 40,000 40,000 Work-in-Process Control 40,000 (specific job) 40,000 Manufacturing Overhead Control Work-in-Process Control (specific job) 40,000 2. No entry until units are completed and transferred out. Then the normal spoilage costs are transferred as part of the cost of good units. Work in Process—Dept. B 40,000 Work in Process—Dept. A 40,000 3. Not applicable No entry. Normal spoilage cost remains in Work-in-Process Control (specific job) DecisiOn PointS The following question-and-answer format summarizes the chapter’s learning objectives. Each decision presents a key question related to a learning objective. The guidelines are the answer to that question. Decision 1. What are spoilage, rework, and scrap? 2. What is the distinction between normal and abnormal spoilage? Guidelines Spoilage refers to units of production that do not meet the specifications required by customers for good units and that are discarded or sold at reduced prices. Spoilage is generally divided into normal spoilage, which is inherent to a particular production process, and abnormal spoilage, which arises because of operational inefficiency. Rework refers to unacceptable units that are subsequently repaired and sold as acceptable finished goods. Scrap is residual material that results from manufacturing a product; it has low total sales value compared with the total sales value of the product. Normal spoilage is inherent in a particular production process and arises when the process is done in an efficient manner. Abnormal spoilage, on the other hand, is not inherent in a particular production process and would not arise under efficient operating conditions. Abnormal spoilage is usually regarded as avoidable and controllable. www.downloadslide.com appendix Decision 3. How do the weighted-average and FIFO methods of process costing calculate the costs of good units and spoilage? 737 Guidelines The weighted-average method combines the costs of beginning inventory with the costs of the current period when determining the costs of good units, which include normal spoilage, and the costs of abnormal spoilage, which are written off as a loss of the accounting period. The FIFO method keeps the costs of beginning inventory separate from the costs of the current period when determining the costs of good units (which include normal spoilage) and the costs of abnormal spoilage, which are written off as a loss of the accounting period. 4. How does inspecting at various stages of completion affect the amount of normal and abnormal spoilage? The cost of spoiled units is assumed to equal all costs incurred in producing spoiled units up to the point of inspection. Spoilage costs therefore vary based on different inspection points. 5. How do job-costing systems account for spoilage? Normal spoilage specific to a job is assigned to that job or, when common to all jobs, is allocated as part of manufacturing overhead. The cost of abnormal spoilage is written off as a loss in the accounting period. 6. How do job-costing systems account for rework? Normal rework specific to a job is assigned to that job or, when common to all jobs, is allocated as part of manufacturing overhead. Cost of abnormal rework is written off as a loss of the accounting period. 7. How is scrap accounted for? Scrap is recognized in a firm’s accounting records either at the time of its sale or at the time of its production. If the scrap is immaterial, it is recognized as revenue when it’s sold. If it’s not immaterial, the net realizable value of the scrap when it’s sold reduces the cost of a specific job or, when common to all jobs, reduces Manufacturing Overhead Control. APPendix Standard-Costing Method and Spoilage The standard-costing method simplifies the computations for normal and abnormal spoilage. To illustrate, we return to the Anzio Company example in the chapter. Suppose Anzio develops the following standard costs per unit for work done in the forming department in July 2017: Direct materials Conversion costs Total manufacturing cost $ 8.50 10.50 $19.00 Assume the same standard costs per unit also apply to the beginning inventory: 1,500 (1,500 * 100%) equivalent units of direct materials and 900 (1,500 * 60%) equivalent units of conversion costs. Hence, the beginning inventory at standard costs is as follows: Direct materials, 1,500 units * $8.50 per unit Conversion costs, 900 units * $10.50 per unit Total manufacturing costs $12,750 9,450 $22,200 Exhibit 18-5, Panel A, presents Steps 1 and 2 for calculating physical and equivalent units. These steps are the same as for the FIFO method described in Exhibit 18-3. Exhibit 18-5, Panel B, presents Steps 3, 4, and 5. www.downloadslide.com 738 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap Standard-Costing Method of Process Costing with Spoilage for the Forming Department for July 2017 exHibit 18-5 PANEL A: Summarize the Flow of Physical Units and Compute Output in Equivalent Units $ % & ' (Step 1) Flow of Production Work in proc ess, beginning (given, p. 722) Started during current period (given, p. 722) To account for Good units completed and transferred out during current period From beginning work in process a [1,500 3 (100% – 100%); 1,500 3 (100% – 60%)] Started and completed (5,500 3 100%; 5,500 3 100%) 10,000 1,500 5,500 Normal Spoilagec (700 3 100%; 700 3 100%) 700 Abnormal Spoilaged (300 3 100%; 300 3 100%) 300 Work in process, ending e (given, p. 722) (2,000 3 100%; 2,000 3 50%) Accounted for Equivalent units of work done in current period Physical Units 1,500 8,500 ( (Step 2) Equivalent Units Direct Conversion Costs Materials 0 600 5,500 5,500 700 700 300 300 2,000 1,000 8,500 8,100 b 2,000 10,000 a Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 60%. b 7,000 physical units completed and transferred out minus 1,500 physical units completed and transferred out from beginning work-in-process inventory. c Normal spoilage is 10% of good units transferred out; 10% 3 7,000 5 700 units. Degree of completion of normal spoilage in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 100%. d Abnormal spoilage 5 Actual spoilage – Normal spoilage 5 1,000 – 700 5 300 units. Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 100%. e Degree of completion in this department: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 50%. PANEL B: Summarize the Total Costs to Account For, Compute the Cost per Equivalent Unit, and Assign Costs to the Units Completed, Spoiled Units, and Units in Ending Work-in-Process Inventory $ % (Step 3) (Step 4) (Step 5) Work in process, beginning (1,500 units) Costs added to beginning work in process in current period Total from beginning inventory before normal spoilage Started and completed before normal spoilage (5,500 units) Normal spoilage (700 units) (A) (B) Work in proc ess, beginning (given, p. 722) Costs added in current period at standard costs Total costs to account for Standard costs per equivalent unit (given, p. 722) Assignment of costs: Good units completed and transferred out (7,000 units): Total costs of good units completed and transferred out Abnormal spoilage (300 units) (C) Work in process, ending (2,000 units) (A) 1 (B) 1(C) Total costs accounted for f Equivalent units of direct materials and conversion costs calculated in Step 2 in Panel A. & ' Total Production Costs $ 22,200 157,300 $179,500 $ 19.00 Direct Materials (1,500 3 $8.50) (8,500 3 $8.50) $85,000 $ 8.50 ( ) Conversion Costs 1 (900 3 $10.50) 1 (8,100 3 $10.50) $94,500 1 $ 10.50 $ 22,200 6,300 28,500 (1,500 3 $8.50) 1 (900 3 $10.50) (0f 3 $8.50) 1 (600 f 3 $10.50) 104,500 13,300 (5,500f 3 $8.50) (700f 3 $8.50) 1 1 (5,500 3 $10.50) f (700 3 $10.50) 146,300 5,700 (300f 3 $8.50) 1 (300 f 3 $10.50) 1 (1,000 f 3 $10.50) $94,500 27,500 $179,500 f (2,000 3 $8.50) $85,000 1 f www.downloadslide.com aSSignment material 739 The costs to account for in Step 3 are at standard costs and, hence, they differ from the costs to account for under the weighted-average and FIFO methods, which are at actual costs. In Step 4, cost per equivalent unit is simply the standard cost: $8.50 per unit for direct materials and $10.50 per unit for conversion costs. The standard-costing method makes calculating equivalent-unit costs unnecessary, so it simplifies process costing. In Step 5, managers assign standard costs to units completed (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to ending work-in-process inventory by multiplying the equivalent units calculated in Step 2 by the standard costs per equivalent unit presented in Step 4. This enables managers to measure and analyze variances in the manner described in the appendix to Chapter 17 (pages 705–707).6 Finally, note that the journal entries corresponding to the amounts calculated in Step 5 are as follows: Finished Goods Work in Process—Forming To record transfer of good units completed in July. Loss from Abnormal Spoilage Work in Process—Forming To record abnormal spoilage detected in July. 6 146,300 146,300 5,700 5,700 For example, from Exhibit 18-5, Panel B, the standard costs for July are direct materials used, 8,500 * $8.50 = $72,250, and conversion costs, 8,100 * $10.50 = $85,050. From page 722, the actual costs added during July are direct materials, $76,500, and conversion costs, $89,100, resulting in a direct materials variance of $72,250 - $76,500 = $4,250 U and a conversion costs variance of $85,050 - $89,100 = $4,050 U. These variances could then be subdivided further as in Chapters 7 and 8; the abnormal spoilage would be part of the efficiency variance. termS to leArn This chapter and the Glossary at the end of the book contain definitions of the following important terms: abnormal spoilage (p. 720) inspection point (p. 721) normal spoilage (p. 720) rework (p. 719) scrap (p. 719) spoilage (p. 719) ASSignment mAteriAl Questions 18-1 18-2 18-3 18-4 18-5 18-6 18-7 18-8 18-9 18-10 18-11 Why is there an unmistakable trend in manufacturing to improve quality? Distinguish among spoilage, rework, and scrap. “Normal spoilage is planned spoilage.” Discuss. “Costs of abnormal spoilage are losses.” Explain. “What has been regarded as normal spoilage in the past is not necessarily acceptable as normal spoilage in the present or future.” Explain. “Units of abnormal spoilage are inferred rather than identified.” Explain. “In accounting for spoiled units, we are dealing with cost assignment rather than cost incurrence.” Explain. “Total input includes abnormal as well as normal spoilage and is, therefore, inappropriate as a basis for computing normal spoilage.” Do you agree? Explain. “The inspection point is the key to the allocation of spoilage costs.” Do you agree? Explain. “The unit cost of normal spoilage is the same as the unit cost of abnormal spoilage.” Do you agree? Explain. “In job costing, the costs of normal spoilage that occur while a specific job is being done are charged to the specific job.” Do you agree? Explain. MyAccountingLab www.downloadslide.com 740 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap 18-12 “The costs of rework are always charged to the specific jobs in which the defects were originally discovered.” Do you agree? Explain. 18-13 “Abnormal rework costs should be charged to a loss account, not to manufacturing overhead.” Do you agree? Explain. 18-14 When is a company justified in inventorying scrap? 18-15 How do managers use information about scrap? MyAccountingLab Multiple-Choice Questions In partnership with: 18-16 All of the following are accurate regarding the treatment of normal or abnormal spoilage by a firm with the exception of: a. Abnormal spoilage is excluded in the standard cost of a manufactured product. b. Normal spoilage is capitalized as part of inventory cost. c. Abnormal spoilage has no financial statement impact. d. Normal and abnormal spoilage units affect the equivalent units of production. 18-17 Which of the following is a TRUE statement regarding the treatment of scrap by a firm? a. b. c. d. Scrap is always allocated to a specific job. Scrap is separated between normal and abnormal scrap. Revenue received from the sale of scrap on a job lowers the total costs for that job. There are costs assigned to scrap. 18-18 Healthy Dinners Co. produces frozen dinners for the health conscious consumer. During the quarter ended September 30, the company had the following cost data: Dinner ingredients Preparation labor Sales and marketing costs Plant production overhead Normal food spoilage Abnormal food spoilage General and administrative expenses $3,550,000 900,000 125,000 50,000 60,000 40,000 75,000 Based on the above, what is the total amount of period expenses reflected in the company’s income statement for the quarter ended September 30? a. $200,000 b. $240,000 c. $290,000 d. $300,000 18-19 Fresh Products, Inc. incurred the following costs during December related to the production of its 162,500 frozen ice cream cone specialty items: Food product labor Ice cream cone ingredients Sales and marketing costs Factory overhead Normal food spoilage Abnormal spoilage $175,000 325,000 10,000 16,000 4,000 3,000 What is the per unit inventory cost allocated to the company’s frozen ice cream cone specialty items for December? a. $3.18 b. $3.20 c. $3.22 d. $3.26 ©2016 DeVry/Becker Educational Development Corp. All Rights Reserved. www.downloadslide.com aSSignment material Exercises 741 MyAccountingLab 18-20 Normal and abnormal spoilage in units. The following data, in physical units, describe a grinding process for January: Work in process, beginning Started during current period To account for 19,300 145,400 164,700 Spoiled units Good units completed and transferred out Work in process, ending Accounted for 12,000 128,000 24,700 164,700 Inspection occurs at the 100% completion stage. Normal spoilage is 5% of the good units passing inspection. 1. Compute the normal and abnormal spoilage in units. 2. Assume that the equivalent-unit cost of a spoiled unit is $8. Compute the amount of potential savings if all spoilage were eliminated, assuming that all other costs would be unaffected. Comment on your answer. Required 18-21 Weighted-average method, spoilage, equivalent units. (CMA, adapted) Consider the following data for November 2017 from MacLean Manufacturing Company, which makes silk pennants and uses a process-costing system. All direct materials are added at the beginning of the process, and conversion costs are added evenly during the process. Spoilage is detected upon inspection at the completion of the process. Spoiled units are disposed of at zero net disposal value. MacLean Manufacturing Company uses the weighted-average method of process costing. Work in process, November 1a Started in November 2017 Good units completed and transferred out during November 2017 Normal spoilage Abnormal spoilage Work in process, November 30b Total costs added during November 2017 Physical Units (Pennants) 1,350 ? 8,800 Direct Materials $ 966 Conversion Costs $ 711 $10,302 $30,055 80 50 1,700 a Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 45%. Degree of completion: direct materials, 100%; conversion costs, 35%. b Compute equivalent units for direct materials and conversion costs. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. Required 18-22 Weighted-average method, assigning costs (continuation of 18-21). For the data in Exercise 18-21, summarize the total costs to account for; calculate the cost per equivalent unit for direct materials and conversion costs; and assign costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work-in-process inventory. Required 18-23 FIFO method, spoilage, equivalent units. Refer to the information in Exercise 18-21. Suppose MacLean Manufacturing Company uses the FIFO method of process costing instead of the weightedaverage method. Compute equivalent units for direct materials and conversion costs. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. Required 18-24 FIFO method, assigning costs (continuation of 18-23). For the data in Exercise 18-21, use the FIFO method to summarize the total costs to account for; calculate the cost per equivalent unit for direct materials and conversion costs; and assign costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work in process. 18-25 Weighted-average method, spoilage. LaCroix Company produces handbags from leather of moderate quality. It distributes the product through outlet stores and department store chains. At LaCroix’s facility in northeast Ohio, direct materials (primarily leather hides) are added at the beginning of the process, Required www.downloadslide.com 742 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap while conversion costs are added evenly during the process. Given the importance of minimizing product returns, spoiled units are detected upon inspection at the end of the process and are discarded at a net disposal value of zero. LaCroix uses the weighted-average method of process costing. Summary data for April 2017 are as follows: $ Required Work in process, beginning inventory (April 1) Degree of completion of beginning work in process Started during April Good units completed and transferred out during April Work in process, ending inventory (April 30) Degree of completion of ending work in process Total costs added during April Normal spoilage as a percentage of good units Degree of completion of normal spoilage Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage % & ' Physical Units 2,400 Direct Materials $21,240 100% Conversion Costs $ 13,332 50% 100% $97,560 75% $111,408 100% 100% 100% 100% 12,000 10,800 2,160 10% 1. For each cost category, calculate equivalent units. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. 2. Summarize the total costs to account for; calculate the cost per equivalent unit for each cost category; and assign costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work in process. 18-26 FIFO method, spoilage. Required 1. Do Exercise 18-25 using the FIFO method. 2. What are the managerial issues involved in selecting or reviewing the percentage of spoilage considered normal? How would your answer to requirement 1 differ if all spoilage were viewed as normal? 18-27 Spoilage, journal entries. Plastique produces parts for use in various industries. Plastique uses a job-costing system. The nature of its process is such that management expects normal spoilage at a rate of 2% of good parts. Data for last month is as follows: Production (units) Good parts produced Direct material cost/unit 10,000 9,750 $ 5.00 The spoiled parts were identified after 100% of the direct material cost was incurred. The disposal value is $2/part. Required 1. Record the journal entries if the spoilage was (a) job specific or (b) common to all jobs. 2. Comment on the differences arising from the different treatment for these two scenarios. 18-28 Recognition of loss from spoilage. Spheres Toys manufactures globes at its San Fernando facility. The company provides you with the following information regarding operations for April 2017: Total globes manufactured Globes rejected as spoiled units Total manufacturing cost 20,000 750 $800,000 Assume the spoiled units have no disposal value. Required 1. What is the unit cost of making the 20,000 globes? 2. What is the total cost of the 750 spoiled units? 3. If the spoilage is considered normal, what is the increase in the unit cost of good globes manufactured as a result of the spoilage? 4. If the spoilage is considered abnormal, prepare the journal entries for the spoilage incurred. www.downloadslide.com aSSignment material 18-29 Weighted-average method, spoilage. LogicCo is a fast-growing manufacturer of computer chips. Direct materials are added at the start of the production process. Conversion costs are added evenly during the process. Some units of this product are spoiled as a result of defects not detectable before inspection of finished goods. Spoiled units are disposed of at zero net disposal value. LogicCo uses the weightedaverage method of process costing. Summary data for September 2017 are as follows: $ Work in process, beginning inventory (September 1) Degree of completion of beginning work in process Started during September Good units completed and transferred out during September Work in process, ending inventory (September 30) Degree of completion of ending work in process Total costs added during September Normal spoilage as a percentage of good units Degree of completion of normal spoilage Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage % & ' Physical Units (Computer Chips) 900 Direct Materials $125,766 100% Conversion Costs $ 10,368 30% 100% $619,650 10% $253,098 100% 100% 100% 100% 2,754 2,500 490 15% 1. For each cost category, compute equivalent units. Show physical units in the first column of your schedule. 2. Summarize the total costs to account for; calculate the cost per equivalent unit for each cost category; and assign costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work in process. Required 18-30 FIFO method, spoilage. Refer to the information in Exercise 18-29. 1. Do Exercise 18-29 using the FIFO method of process costing. 2. Should LogicCo’s managers choose the weighted-average method or the FIFO method? Explain briefly. Required 18-31 Standard-costing method, spoilage. Refer to the information in Exercise 18-29. Suppose LogicCo determines standard costs of $215 per equivalent unit for direct materials and $92 per equivalent unit for conversion costs for both beginning work in process and work done in the current period. 1. Do Exercise 18-29 using the standard-costing method. 2. What issues should the manager focus on when reviewing the equivalent units calculation? Required 18-32 Spoilage and job costing. (L. Bamber) Barrett Kitchens produces a variety of items in accordance with special job orders from hospitals, plant cafeterias, and university dormitories. An order for 2,100 cases of mixed vegetables costs $9 per case: direct materials, $4; direct manufacturing labor, $3; and manufacturing overhead allocated, $2. The manufacturing overhead rate includes a provision for normal spoilage. Consider each requirement independently. 1. Assume that a laborer dropped 420 cases. Suppose part of the 420 cases could be sold to a nearby prison for $420 cash. Prepare a journal entry to record this event. Calculate and explain briefly the unit cost of the remaining 1,680 cases. 2. Refer to the original data. Tasters at the company reject 420 of the 2,100 cases. The 420 cases are disposed of for $840. Assume that this rejection rate is considered normal. Prepare a journal entry to record this event, and do the following: a. Calculate the unit cost if the rejection is attributable to exacting specifications of this particular job. b. Calculate the unit cost if the rejection is characteristic of the production process and is not attributable to this specific job. c. Are unit costs the same in requirements 2a and 2b? Explain your reasoning briefly. 3. Refer to the original data. Tasters rejected 420 cases that had insufficient salt. The product can be placed in a vat, salt can be added, and the product can be reprocessed into jars. This operation, which is considered normal, will cost $420. Prepare a journal entry to record this event and do the following: a. Calculate the unit cost of all the cases if this additional cost was incurred because of the exacting specifications of this particular job. Required 743 www.downloadslide.com 744 Chapter 18 Spoilage, rework, and SCrap b. Calculate the unit cost of all the cases if this additional cost occurs regularly because of difficulty in seasoning. c. Are unit costs the same in requirements 3a and 3b? Explain your reasoning briefly. 18-33 Reworked units, costs of rework. Heyer Appliances assembles dishwashers at its plant in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. In February 2017, 60 circulation motors that cost $110 each (from a new supplier who subsequently went bankrupt) were defective and had to be disposed of at zero net disposal value. Heyer Appliances was able to rework all 60 dishwashers by substituting new circulation motors purchased from one of its existing suppliers. Each replacement motor cost $125. 1. What alternative approaches are there to account for the materials cost of reworked units? 2. Should Heyer Appliances use the $110 circulation motor or the $125 motor to calculate the cost of materials reworked? Explain. 3. What other costs might Heyer Appliances include in its analysis of the total costs of rework due to the circulation motors purchased from the (now) bankrupt supplier? Required 18-34 Scrap, job costing. The Russell Company has an extensive job-costing facility that uses a variety of metals. Consider each requirement independently. 1. Job 372 uses a particular metal alloy that is not used for any other job. Assume that scrap is material in amount and sold for $480 quickly after it is produced. Prepare the journal entry. 2. The scrap from Job 372 consists of a metal used by many other jobs. No record is maintained of the scrap generated by individual jobs. Assume that scrap is accounted for at the time of its sale. Scrap totaling $4,500 is sold. Prepare two alternative journal entries that could be used to account for the sale of scrap. 3. Suppose the scrap generated in requirement 2 is returned to the storeroom for future use, and a journal entry is made to record the scrap. A month later, the scrap is reused as direct material on a subsequent job. Prepare the journal entries to record these transactions. Required Problems MyAccountingLab 18-35 Weighted-average method, spoilage. World Class Steaks is a meat-processing firm based in Texas. It operates under the weighted-average method of process costing and has two departments: preparation (prep) and shipping. For the prep department, conversion costs are added evenly during the process, and direct materials are added at the beginning of the process. Spoiled units are detected upon inspection at the end of the prep process and are disposed of at zero net disposal value. All completed work is transferred to the shipping department. Summary data for May follow: $ World Class Steaks: Preparation (Prep) Department Work in process, beginning inventory (May 1) Degree of completion of beginning work in process Started during May Good units completed and transferred out during May Work in process, ending inventory (May 31) Degree of completion of ending work in process Total costs added during May Normal spoilage as a percentage of good units Degree of completion of normal spoilage Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage % & ' Physical Units 7,200 Direct Materials $ 10,632 100% Conversion Costs $ 2,778 50% 100% $111,000 25% $89,664 100% 100% 100% 100% 60,000 49,200 10,080 10% Required For the prep department, summarize the total costs to account for and assign those costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work in process. (Problem 18-37 explores additional facets of this problem.) Required Do Problem 18-35 using the FIFO method of process costing. (Problem 18-38 explores additional facets of this problem.) 18-36 FIFO method, spoilage. Refer to the information in Problem 18-35. www.downloadslide.com aSSignment material 18-37 Weighted-average method, shipping department (continuation of 18-35). In the shipping depart- ment of World Class Steaks, conversion costs are added evenly during the process, and direct materials are added at the end of the process. Spoiled units are detected upon inspection at the end of the process and are disposed of at zero net disposal value. All completed work is transferred to the next department. The transferred-in costs for May equal the total cost of good units completed and transferred out in May from the prep department, which were calculated in Problem 18-35 using the weighted-average method of process costing. Summary data for May follow. $ World Class Steaks: Shipping Department Work in process, beginning inventory (May 1) Degree of completion of beginning work in process Started during May Good units completed and transferred out during May Work in process, ending inventory (May 31) Degree of completion of ending work in process Total costs added during May Normal spoilage as a percentage of good units Degree of completion of normal spoilage Degree of completion of abnormal spoilage % & ' ( Physical Units 25,200 Transferred-In Costs $67,397 100% Direct Materials $ 0 0% Conversion Costs $ 46,950 70% 0% $11,520 40% 81,690 $ 100% 100% 100% 100% 49,200 52,800 16,800 100% ? 7% For the shipping department, use the weighted-average method to summarize the total costs to account for and assign those costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work in process. Required 18-38 FIFO method, shipping department (continuation of 18-36). Refer to the information in Problem 18-37 except that the transferred-in costs of beginning work in process on May 1 are $66,180 (instead of $67,397). Transferred-in costs for May equal the total cost of good units completed and transferred out in May from the prep department, as calculated in Problem 18-36 using the FIFO method of process costing. For the shipping department, use the FIFO method to summarize the total costs to account for and assign those costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work in process. 18-39 Physical units, inspection at various levels of completion, weighted-average process costing. SunEnergy produces solar panels. A key step in the conversion of raw silicon to a completed solar panel occurs in the assembly department, where lightweight photovoltaic cells are assembled into modules and connected on a frame. In this department, materials are added at the beginning of the process and conversion takes place uniformly. At the start of November 2017, SunEnergy’s assembly department had 2,400 panels in beginning work in process, which were 100% complete for materials and 40% complete for conversion costs. An additional 12,000 units were started in the department in November, and 3,600 units remain in work in process at the end of the month. These unfinished units are 100% complete for materials and 70% complete for conversion costs. The assembly department had 1,800 spoiled units in November. Because of the difficulty of keeping moisture out of the modules and sealing the photovoltaic cells between layers of glass, normal spoilage is approximately 12% of good units. The department’s costs for the month of November are as follows: Direct materials costs Conversion costs Beginning WIP $ 76,800 123,000 Costs Incurred During Period $ 240,000 1,200,000 Required 745 www.downloadslide.com 746 Chapter 18 Required Spoilage, rework, and SCrap 1. Using the format on page 728, compute the normal and abnormal spoilage in units for November, assuming the inspection point is at (a) the 30% stage of completion, (b) the 60% stage of completion, and (c) the 100% stage of completion. 2. Refer to your answer in requirement 1. Why are there different amounts of normal and abnormal spoilage at different inspection points? 3. Now assume that the assembly department inspects at the 60% stage of completion. Using the weighted-average method, calculate the cost of units transferred out, the cost of abnormal spoilage, and the cost of ending inventory for the assembly department in November. 18-40 Spoilage in job costing. Jellyfish Machine Shop is a manufacturer of motorized carts for vacation resorts. Patrick Cullin, the plant manager of Jellyfish, obtains the following information for Job #10 in August 2017. A total of 46 units were started, and 6 spoiled units were detected and rejected at final inspection, yielding 40 good units. The spoiled units were considered to be normal spoilage. Costs assigned prior to the inspection point are $1,100 per unit. The current disposal price of the spoiled units is $235 per unit. When the spoilage is detected, the spoiled goods are inventoried at $235 per unit. Required 1. What is the normal spoilage rate? 2. Prepare the journal entries to record the normal spoilage, assuming the following: a. The spoilage is related to a specific job. b. The spoilage is common to all jobs. c. The spoilage is considered to be abnormal spoilage. 18-41 Rework in job costing, journal entry (continuation of 18-40). Assume that the 6 spoiled units of Jellyfish Machine Shop’s Job #10 can be reworked for a total cost of $1,800. A total cost of $6,600 associated with these units has already been assigned to Job #10 before the rework. Required Prepare the journal entries for the rework, assuming the following: a. The rework is related to a specific job. b. The rework is common to all jobs. c. The rework is considered to be abnormal. 18-42 Scrap at time of sale or at time of production, journal entries (continuation of 18-40). Assume that Job #10 of Jellyfish Machine Shop generates normal scrap with a total sales value of $700 (it is assumed that the scrap returned to the storeroom is sold quickly). Required Prepare the journal entries for the recognition of scrap, assuming the following: a. b. c. d. The value of scrap is immaterial and scrap is recognized at the time of sale. The value of scrap is material, is related to a specific job, and is recognized at the time of sale. The value of scrap is material, is common to all jobs, and is recognized at the time of sale. The value of scrap is material, and scrap is recognized as inventory at the time of production and is recorded at its net realizable value. 18-43 Physical units, inspection at various stages of completion. Chemet manufactures chemicals in a continuous process. The company combines various materials in a specially configured machine at the beginning of the process, and conversion is considered uniform through the period. Occasionally, the chemical reactions among the materials do not work as expected and the output is then considered spoiled. Normal spoilage is 4% of the good units that pass inspection. The following information pertains to March 2017: Beginning inventory 2,500 units (100% complete for materials; 25% complete for conversion costs) Units started 30,000 Units in ending work in process 2,100 (100% complete for materials; 70% complete for conversion costs) Chemet had 1,900 spoiled units in March 2017. Required Using the format on page 728, compute the normal and abnormal spoilage in units, assuming the inspection point is at (a) the 20% stage of completion, (b) the 45% stage of completion, and (c) the 100% stage of completion. 18-44 Weighted-average method, inspection at 80% completion. (A. Atkinson) The Horsheim Company is a furniture manufacturer with two departments: molding and finishing. The company uses the www.downloadslide.com aSSignment material weighted-average method of process costing. In August, the following data were recorded for the finishing department: Units of beginning work-in-process inventory Percentage completion of beginning work-in-process units Units started Units completed Units in ending inventory Percentage completion of ending work-in-process units Spoiled units Total costs added during current period: Direct materials Direct manufacturing labor Manufacturing overhead Work in process, beginning: Transferred-in costs Conversion costs Cost of units transferred in during current period 25,000 25% 175,000 125,000 50,000 95% 25,000 $1,638,000 $1,589,000 $1,540,000 $ 207,250 $ 105,000 $1,618,750 Conversion costs are added evenly during the process. Direct material costs are added when production is 90% complete. The inspection point is at the 80% stage of production. Normal spoilage is 10% of all good units that pass inspection. Spoiled units are disposed of at zero net disposal value. 1. For August, summarize total costs to account for and assign these costs to units completed and transferred out (including normal spoilage), to abnormal spoilage, and to units in ending work in process. 2. What are the managerial issues involved in determining the percentage of spoilage considered normal? How would your answer to requirement 1 differ if all spoilage were treated as normal? Required 18-45 Job costing, classifying spoilage, ethics. Flextron Company is a contract manufacturer for a variety of pharmaceutical and over-the-counter products. It has a reputation for operational excellence and boasts a normal spoilage rate of 2% of normal input. Normal spoilage is recognized during the budgeting process and is classified as a component of manufacturing overhead when determining the overhead rate. Lynn Sanger, one of Flextron’s quality control managers, obtains the following information for Job No. M102, an order from a consumer products company. The order was completed recently, just before the close of Flextron’s fiscal year. The units will be delivered early in the next accounting period. A total of 128,500 units were started, and 6,000 spoiled units were rejected at final inspection, yielding 122,500 good units. Spoiled units were sold at $4 per unit. Sanger indicates that all spoilage was related to this specific job. The total costs for all 128,500 units of Job No. M102 follow. The job has been completed, but the costs are yet to be transferred to Finished Goods. Direct materials Direct manufacturing labor Manufacturing overhead Total manufacturing costs $ 979,000 840,000 1,650,500 $3,469,500 1. Calculate the unit quantities of normal and abnormal spoilage. 2. Prepare the journal entries to account for Job No. M102, including spoilage, disposal of spoiled units, and transfer of costs to the Finished Goods account. 3. Flextron’s controller, Vince Chadwick, tells Marta Suarez, the management accountant responsible for Job No. M102, the following: “This was an unusual job. I think all 6,000 spoiled units should be considered normal.” Suarez knows that the work involved in Job No. M102 was not uncommon and that Flextron’s normal spoilage rate of 2% is the appropriate benchmark. She feels Chadwick made these comments because he wants to show a higher operating income for the year. a. Prepare journal entries, similar to requirement 2, to account for Job No. M102 if all spoilage were considered normal. How will operating income be affected if all spoilage is considered normal? b. What should Suarez do in response to Chadwick’s comment? Required 747