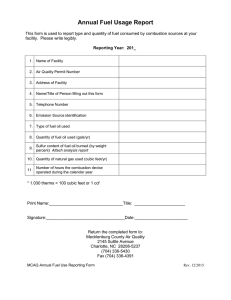

Performance of Waste Lubrication Oil Burner for Process

advertisement