Understanding Economics A Contemporary Perspective Eighth Edition (Mark Lovewell)

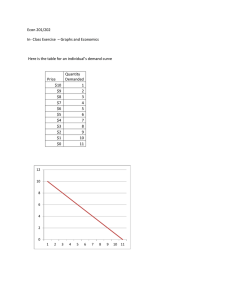

advertisement