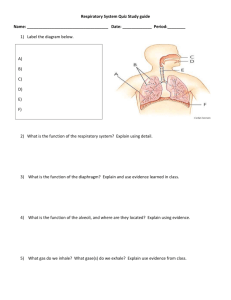

Histology, Respiratory Epithelium Nakisa Kia'i Introduction The respiratory system is constantly filtering through the external environment as humans breathe air. The airways must maintain the ability to clear inhaled pathogens, allergens, and debris to maintain homeostasis and prevent inflammation. The respiratory system subdivides into a conducting portion and a respiratory portion. The majority of the respiratory tree, from the nasal cavity to the bronchi, is lined by pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelium. The bronchioles are lined by simple columnar to the cuboidal epithelium, and the alveoli possess a lining of thin squamous epithelium that allows for gas exchange. Structure There are four main histological layers within the respiratory system: respiratory mucosa, which includes epithelium and supporting lamina propria, submucosa, cartilage and/or muscular layer and adventitia. Respiratory epithelium is ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium found lining most of the respiratory tract; it is not present in the larynx or pharynx. The epithelium classifies as pseudostratified; though it is a single layer of cells along the basement membrane, the alignment of the nuclei is not in the same plane and appears as multiple layers. The role of this unique type of epithelium is to function as a barrier to pathogens and foreign particles; however, it also operates by preventing infection and tissue injury via the use of the mucociliary elevator. The Conducting Portion The conducting piece of the respiratory system consists of the nasal cavity, trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles. The luminal surfaces of this entire portion have a lining of ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Their role is to secrete mucus that serves as the first line of defense against incoming environmental pathogens. Cilia move the mucus-bound particulate up and away for expulsion from the body. The various types and abundance of cells are dependent on which region of the airway they are.[1] In the most proximal airway, hyaline cartilage rings support the larger respiratory passages, namely, the trachea and bronchi, to facilitate the passage of air. Three major cell types are found in this region: ciliated, non-ciliated secretory cells, and basal cells. Ciliated cells, each lined with 200 to 300 cilia, account for more than half of all epithelial cells in the conducting airway. As the degree of branching within the airway tree continues, the epithelium gradually changes from pseudostratified to simple cuboidal; and the predominant cells become nonciliated cells, Clara cells. The Gas-Exchange Portion The respiratory or gas-exchange region of the lung is composed of millions of alveoli, which are lined by an extremely thin, simple squamous epithelium that allows for the easy diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Additionally, cuboidal, surfactant-secreting cells, Type II pneumocytes, are also found lining the walls of alveoli. Surfactant, which is primarily composed of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine, has a vital role in lowering the surface tension of water to allow for effective gas exchange.[1] Type I pneumocytes are flattened cells that create a very thin diffusion barrier for gases. Tight junctions are found connecting one cell to another.[2] The principal functions of Type I pneumocytes are gas exchange and fluid transport. Type II Pneumocytes secrete surfactant, which decreases the surface area between thin alveolar walls, and stops alveoli from collapsing during exhalation. These cells connect to the epithelium and other constituent cells by tight junctions. Type II pneumocytes also play a vital role in acting as progenitor cells to replace injured or damaged Type I pneumocytes.[3] Function Just as the skin protects humans from external pathogens and irritants, the respiratory epithelium acts to protect and effectively clear the airways and lungs of inhaled pathogens and irritants. The division of the respiratory system into conducting and respiratory airways delineates their function and roles. The conducting portion, consisting of the nose, pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles, which all serve to humidify, warm, filter air. The respiratory portion is involved in gas exchange. There are three major types of cells found in respiratory epithelium, and each holds a vital role in regulating how humans breathe. If any of these components of the barrier are not properly functioning, the body becomes susceptible to acquiring infections, pathogens or inducing inflammation, and disturbing hemostasis. Humidification & Warming Humidification requires serous and mucous secretions, and warming relies on the extensive capillary network that lays within the alveoli. The alveoli are also extensively enveloped by capillaries that allow for air to be conditioned and heated by the vascular plexus that surrounds them and provides for heat-exchange. The branching of the arteries and veins of the pulmonary system follow a similar branching pattern to that of the airway tree. The walls of the pulmonary arteries and veins are more delicate than the vasculature in other regions of the body, as the pulmonary circulation functions at a lower pressure than the systemic circulation. Filtration Filtration occurs by the trapping mechanism of mucus secretions and ciliary beating. This process allows trapped particulate to move towards the throat where mucus is swallowed or expelled by the body. Goblet cells are columnar epithelial cells that secrete high molecular weight mucin glycoproteins into the lumen of the airway and provide moisture to the epithelium while trapping incoming particulate and pathogens. In a healthy airway, ciliated cells are columnar epithelial cells that are modified with hundreds of hair-like projections, beating at a rapid frequency of approximately 8 to 20 Hz, mobilizing the mucus that is found resting on it.[4] Oxidant defense & Response to Injury Cells found in the respiratory epithelium are continually fighting off inhaled particulate and pathogens and regenerating themselves after injury. Basal cells, which are small, nearly cuboidal cells, attached to the basement membrane by hemidesmosomes, can differentiate into other cell types found within the epithelium. Basal cells provide an attachment site for ciliated and goblet cells to the basal lamina. They also respond to injury and act in oxidant defense of the airway epithelium and transepithelial water movement. Gas Exchange Within the hundreds of millions of microscopic alveolar sacs, the exchange of oxygen for carbon dioxide occurs. Inhaled air diffuses through the alveoli into the pulmonary capillaries, and at the same time, carbon dioxide from deoxygenated blood diffuses into the capillaries then into the alveoli and is expelled through the airways as exhalation occurs. Microscopy Light Light microscopy of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained samples of respiratory tissue reveals pseudostratified epithelium. The term “pseudostratified” is given to this type of epithelium as it appears to be stratified, but all of the component cells are actually attached to one underlying basement membrane. Nuclei appear at varying levels, causing the appearance of stratified epithelium. With H&E staining viewed under light microscopy, the basement membrane appears as a clearly delineated pink line.[5] Goblet cells, with mucinogen granules, also are found scattered amongst the epithelium, and basal cells are present at the basal aspect of the epithelium, acting as progenitor cells for other cell types. The cells that reach the free or apical surface of the epithelium are ciliated, appearing with thin, ‘hair-like’ projections. Each cilium is given rise to by a basal body, which appears as a dense eosinophilic line.[6] The epithelium of the trachea will appear as a narrow pink-staining region immediately basal to the epithelium as a result of its unusually thick basement membrane. Outside the connective tissue layers, rings of C-shaped cartilage keep the lumen of the trachea patent. The transition from the trachea to bronchi is made apparent by the appearance “plates” instead of C-shaped hyaline rings.[7] Additionally, a layer of smooth muscle is present between the lamina propria and submucosa.[7] The bronchioles can be differentiated from the bronchi by the absence in cartilaginous structures and the absence of glands. The transition to respiratory bronchioles shows by the presence of alveoli in their walls and the gradual reduction of the height of epithelium. Clusters of alveoli, called alveolar sacs, become visible, appearing as small knobs of smooth muscle, elastic fibers, and collagen. Microscopy Electron Electron microscopy (EM) can be used to visualize individual cell types and ultrastructural features of epithelium found within respiratory tissue samples. At the level of the trachea and tracheal lining, electron microscopy delineates the different cell types: basal cells, goblet cells, and ciliated cells, as well as their associated organelles and cytoplasmic components. Ciliated epithelium with microvilli are seen well under EM, a cross-section of cilia allows for visualization of the typical 9+2 arrangements of microtubules within the cytoplasm.[4] The level of the alveolus reveals the extremely thin air-blood barrier made up of Type I pneumocytes, capillary endothelium, and the fused basal lamina.[8] Additionally, Type II pneumocytes are seen distinctively from the more thin, delicate Type I pneumocytes. Type II cells contain lamellar bodies, rough endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi and reticular fibers, as well as microvilli. Pathophysiology A number of diseases affect the respiratory system, which may be due to some degree of defective barrier function, a genetic mutation or an inflammatory process. The following discussion outlines a few major diseases that affect respiration. Though not comprehensive, the importance of the proper functioning of the respiratory system and what occurs when a component is malfunctioning may be appreciated based on the few selected diseases discussed below. Asthma Asthma is an inflammatory disease that results in remodeling of the airway walls and causes a hyperreactivity response from environmental triggers, with the overproduction of mucus.[9] Asthma is a common and chronic health condition that affects both adults and children. The incidence is increasing and poses a strong concern for the impacts on health, economic burden, and environmental quality.[10] The cause of asthma is inflammation and edema of the airway that results in bronchospasms that block air entry into the lungs. It may be triggered by environmental factors such as dust, pollen, debris, and pathogens. The response to such triggers is bronchoconstriction, a process in which smooth muscle tightens and narrows the caliber of the bronchi and bronchioles, resulting in wheezing and shortness of breath. Bronchoconstriction occurs through a series of complex interactions between the mucosal epithelium, mast cells, smooth muscles, and the parasympathetic nervous system.[11] Cystic Fibrosis Cystic fibrosis is a disease that once had a life expectancy of a few months and now has a median lifespan of about 40 years.[12] It requires early diagnosis and optimized, mutation-specific treatment to maintain a quality of life for patients. Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive pathology caused by a mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene, CFTR, most commonly the phe508del gene.[13] CFTR protein functions as an ion channel that regulates the amount of liquid through the secretion of chloride and inhibition of sodium absorption from exocrine glands. Chloride and bicarbonate transport play a role in regulating the thickness of the epithelial lining fluid, maintaining pH and sensing the presence of incoming pathogens or irritants. When uncontrolled, the increased sodium reabsorption causes water to follow and results in thick mucus secretions in nearly every organ system.[13] Though thousands of mutations of the CFTR have been described, each mutation manifests with varying effects on the gene and can result in differing phenotypic manifestations in patients, some resulting in more mild disease, others in much more severe prognosis. Cystic fibrosis may affect multiple organ systems, from the lungs to the digestive tract, the pancreas, the liver or the reproductive organs.[14] In the majority of patients, Cystic fibrosis leads to chronic, progressive lung disease and eventually death. Recurrent and infectious exacerbations lead to structural changes and damage to the respiratory system. These complications, in turn, dictate the treatment goals for this condition; to improve mucociliary clearance and to reduce the frequency of bacterial infections while aiming to enhance the quality of life.[12] Ciliary Dyskinesia The respiratory system relies heavily on the ability of cilia to move mucus and inhaled materials up into the proximal airways and away from the lower respiratory tract. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) often presents with situs abnormalities, chronic sinus or pulmonary diseases, and abnormal sperm motility. Ciliary movement plays a role in many organs of the body. When impaired, this manifests in several organ systems. In the respiratory system, impaired mucociliary clearance occurs and results in recurrent infections of the sinuses, ears, and lungs. In the reproductive tract, both sperm motility from flagellae and the fimbriae of fallopian tubes are affected and often lead to infertility. Situs invertus occurs as a result of defective cilia during embryogenesis, as normal functioning cilia are required in the visceral rotation of organs.[4] The diagnosis of PCD, though complex and often missed or misdiagnosed, frequently involves analysis of cilia at an ultrastructural level and molecular genetic testing with one of the 33 genes associated with PCD.[15] The triad of chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, and situs invertus, resulting from ciliary dyskinesia are known as Kartagener syndrome.[4] Clinical Significance The clinical significance of respiratory diseases in the context of histology and function is a complex and broad topic. There is a multitude of conditions and diseases that involve the respiratory system. Below is a list of diseases involving the respiratory system and its constituents. An understanding of the microanatomy and functioning of the respiratory system is key to the mechanism of each of the diseases listed below. Bronchial Diseases Asthma Bronchiectasis Bronchitis Bronchopneumonia Tracheobronchomalacia Bronchogenic cyst Ciliary Motility Disorders Kartagener syndrome Laryngeal Diseases Laryngitis Laryngomalacia Vocal cord paralysis Neoplasms Lung Diseases Acute chest syndrome A-1 antitrypsin deficiency Cystic fibrosis Hemoptysis Pulmonary hypertension Lung abscess Neoplasms Pneumonia Pulmonary edema Pulmonary embolism Atelectasis Tuberculosis Pleural Diseases Chylothorax Hemothorax Hydrothorax Pleural effusion Tuberculosis, pleural Infections Neoplasms Review Questions References 1. Rokicki W, Rokicki M, Wojtacha J, Dżeljijli A. The role and importance of club cells (Clara cells) in the pathogenesis of some respiratory diseases. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2016 Mar;13(1):26-30. [PMC free article: PMC4860431] [PubMed: 27212975] 2. Frank JA. Claudins and alveolar epithelial barrier function in the lung. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012 Jun;1257:175-83. [PMC free article: PMC4864024] [PubMed: 22671604] 3. Reid L, Meyrick B, Antony VB, Chang LY, Crapo JD, Reynolds HY. The mysterious pulmonary brush cell: a cell in search of a function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Jul 01;172(1):136-9. [PMC free article: PMC2718446] [PubMed: 15817800] 4. Mirra V, Werner C, Santamaria F. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia: An Update on Clinical Aspects, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Future Treatment Strategies. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:135. [PMC free article: PMC5465251] [PubMed: 28649564] 5. Ali MY. Histology of the human nasopharyngeal mucosa. J Anat. 1965 Jul;99(Pt 3):657-72. [PMC free article: PMC1270703] [PubMed: 5857093] 6. Bayless BA, Giddings TH, Winey M, Pearson CG. Bld10/Cep135 stabilizes basal bodies to resist cilia-generated forces. Mol Biol Cell. 2012 Dec;23(24):4820-32. [PMC free article: PMC3521689] [PubMed: 23115304] 7. Furlow PW, Mathisen DJ. Surgical anatomy of the trachea. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018 Mar;7(2):255-260. [PMC free article: PMC5900092] [PubMed: 29707503] 8. Knudsen L, Ochs M. The micromechanics of lung alveoli: structure and function of surfactant and tissue components. Histochem Cell Biol. 2018 Dec;150(6):661-676. [PMC free article: PMC6267411] [PubMed: 30390118] 9. Kudo M, Ishigatsubo Y, Aoki I. Pathology of asthma. Front Microbiol. 2013 Sep 10;4:263. [PMC free article: PMC3768124] [PubMed: 24032029] 10. Zein JG, Udeh BL, Teague WG, Koroukian SM, Schlitz NK, Bleecker ER, Busse WB, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Comhair SA, Fitzpatrick AM, Israel E, Wenzel SE, Holguin F, Gaston BM, Erzurum SC., Severe Asthma Research Program. Impact of Age and Sex on Outcomes and Hospital Cost of Acute Asthma in the United States, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157301. [PMC free article: PMC4905648] [PubMed: 27294365] 11. Bacsi A, Pan L, Ba X, Boldogh I. Pathophysiology of bronchoconstriction: role of oxidatively damaged DNA repair. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb;16(1):59-67. [PMC free article: PMC4940044] [PubMed: 26694039] 12. Naehrig S, Chao CM, Naehrlich L. Cystic Fibrosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017 Aug 21;114(33-34):564-574. [PMC free article: PMC5596161] [PubMed: 28855057] 13. Davies JC, Alton EW, Bush A. Cystic fibrosis. BMJ. 2007 Dec 15;335(7632):1255-9. [PMC free article: PMC2137053] [PubMed: 18079549] 14. Stanke F. The Contribution of the Airway Epithelial Cell to Host Defense. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:463016. [PMC free article: PMC4491388] [PubMed: 26185361] 15. Zariwala MA, Knowles MR, Leigh MW. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle; Seattle (WA): Jan 24, 2007. [PubMed: 20301301]