Warren Reeve Duchac

MANAGERIAL

ACCOUNTING

10e

Carl S. Warren

Professor Emeritus of Accounting

University of Georgia, Athens

James M. Reeve

Professor Emeritus of Accounting

University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Jonathan E. Duchac

Professor of Accounting

Wake Forest University

This page intentionally left blank

Warren Reeve Duchac

MANAGERIAL

ACCOUNTING

10e

Carl S. Warren

Professor Emeritus of Accounting

University of Georgia, Athens

James M. Reeve

Professor Emeritus of Accounting

University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Jonathan E. Duchac

Professor of Accounting

Wake Forest University

Managerial Accounting, 10e

Warren Reeve Duchac

VP/Editorial Director: Jack W. Calhoun

Editor in Chief: Rob Dewey

Executive Editor: Sharon Oblinger

Developmental Editor: Aaron Arnsparger

Editorial Assistant: Heather McAuliffe

Marketing Manager: Steven E. Joos

Marketing Coordinator: Gretchen Wildauer

Senior Media Editor: Scott Hamilton

Senior Content Project Manager: Cliff Kallemeyn

Art Director: Stacy Shirley

Senior Frontlist Buyer: Doug Wilke

Production: LEAP Publishing Services, Inc.

© 2009, 2007 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the

copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used

in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical,

including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning,

digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted under

Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For permission to use material from this text or product,

submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions

Further permission questions can be emailed to

permissionrequest@cengage.com

Composition: GGS Book Services, Inc.

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at

Internal Design: Mike Stratton/Patti Hudepohl/Beckmeyer

Design

Cengage Learning Academic Resource Center, 1-800-423-0563

Cover Design: Beckmeyer Design

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008935463

Cover Image: Getty Images

Student Edition

ISBN 13: 978-0-324-66382-2

ISBN 10: 0-324-66382-X

Instructor Edition

ISBN 13: 978-0-324-66387-7

ISBN 10: 0-324-66387-0

South-Western Cengage Learning

5191 Natorp Boulevard

Mason, OH 45040

USA

Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by

Nelson Education, Ltd.

For your course and learning solutions, visit

www.cengage.com

Purchase any of our products at your local college store or at our

preferred online store www.ichapters.com

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 10 09 08

The Author Team

Carl S. Warren

Dr. Carl S. Warren is Professor Emeritus of Accounting at the University of Georgia,

Athens. Dr. Warren has taught classes at the University of Georgia, University of Iowa,

Michigan State University, and University of Chicago. Professor Warren focused his

teaching efforts on principles of accounting and auditing. He received his Ph.D. from

Michigan State University and his B.B.A. and M.A. from the University of Iowa. During

his career, Dr. Warren published numerous articles in professional journals, including

The Accounting Review, Journal of Accounting Research, Journal of Accountancy, The CPA

Journal, and Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory. Dr. Warren has served on numerous

committees of the American Accounting Association, the American Institute of Certified

Public Accountants, and the Institute of Internal Auditors. He has also consulted with

numerous companies and public accounting firms. Warren’s outside interests include

playing handball, golfing, skiing, backpacking, and fly-fishing.

James M. Reeve

Dr. James M. Reeve is Professor Emeritus of Accounting and Information Management at

the University of Tennessee. Professor Reeve taught on the accounting faculty for 25

years, after graduating with his Ph.D. from Oklahoma State University. His teaching

effort focused on undergraduate accounting principles and graduate education in the

Master of Accountancy and Senior Executive MBA programs. Beyond this, Professor

Reeve is also very active in the Supply Chain Certification program, which is a major

executive education and research effort of the College. His research interests are varied

and include work in managerial accounting, supply chain management, lean manufacturing, and information management. He has published over 40 articles in academic and

professional journals, including the Journal of Cost Management, Journal of Management

Accounting Research, Accounting Review, Management Accounting Quarterly, Supply Chain

Management Review, and Accounting Horizons. He has consulted or provided training

around the world for a wide variety of organizations, including Boeing, Procter and

Gamble, Norfolk Southern, Hershey Foods, Coca-Cola, and Sony. When not writing

books, Professor Reeve plays golf and is involved in faith-based activities.

Jonathan Duchac

Dr. Jonathan Duchac is the Merrill Lynch and Co. Professor of Accounting and Director of

the Program in Enterprise Risk Management at Wake Forest University. He earned his

Ph.D. in accounting from the University of Georgia and currently teaches introductory and

advanced courses in financial accounting. Dr. Duchac has received a number of awards

during his career, including the Wake Forest University Outstanding Graduate Professor

Award, the T.B. Rose award for Instructional Innovation, and the University of Georgia

Outstanding Teaching Assistant Award. In addition to his teaching responsibilities, Dr.

Duchac has served as Accounting Advisor to Merrill Lynch Equity Research, where he

worked with research analysts in reviewing and evaluating the financial reporting practices of public companies. He has testified before the U.S. House of Representatives, the

Financial Accounting Standards Board, and the Securities and Exchange Commission; and

has worked with a number of major public companies on financial reporting and accounting policy issues. In addition to his professional interests, Dr. Duchac is the Treasurer of

The Special Children’s School of Winston-Salem; a private, nonprofit developmental day

school serving children with special needs. Dr. Duchac is an avid long-distance runner,

mountain biker, and snow skier. His recent events include the Grandfather Mountain

Marathon, the Black Mountain Marathon, the Shut-In Ridge Trail run, and NO MAAM

(Nocturnal Overnight Mountain Bike Assault on Mount Mitchell).

v

Leading by Example

For nearly 80 years, Accounting has been used effectively to teach generations of businessmen and women. The text has been used by millions of business students. For

many, this book provides the only exposure to accounting principles that they will ever

receive. As the most successful business textbook of all time, it continues to introduce

students to accounting through a variety of time-tested ways.

The previous edition, 9e, started a new journey into learning more about the

changing needs of accounting students through a variety of new and innovative

research and development methods. Our Blue Sky Workshops brought accounting faculty from all over the country into our book development process in a very direct and

creative way. Many of the features and themes present in this text are a result of the collaboration and countless conversations we’ve had with accounting instructors over the

last several years. 10e continues to build on this philosophy and strives to be reflective

of the suggestions and feedback we receive from instructors and students on an ongoing basis. We’re very happy with the results, and think you’ll be pleased with the

improvements we’ve made to the text.

The original author of Accounting, James McKinsey, could not have imagined the

success and influence this text has enjoyed or that his original vision would continue to

lead the market into the twenty-first century. As the current authors, we appreciate the

responsibility of protecting and enhancing this vision, while continuing to refine it to

meet the changing needs of students and instructors. Always in touch with a tradition

of excellence but never satisfied with yesterday’s success, this edition enthusiastically

embraces a changing environment and continues to proudly lead the way. We sincerely

thank our many colleagues who have helped to make it happen.

“The teaching of accounting is no longer designed to train professional accountants

only. With the growing complexity of business and the constantly increasing difficulty

of the problems of management, it has become essential that everyone who aspires to a

position of responsibility should have a knowledge of the fundamental principles of

accounting.”

— James O. McKinsey, Author, first edition, 1929

vi

Leading by Example

Textbooks continue to play an invaluable role in the teaching and learning

environment. Continuing our focus from previous editions, we reached

out to accounting teachers in an effort to improve the textbook presentation. New for this edition, we have extended our discussions to reach out

to students directly in order to learn what they value in a textbook. Here’s

a preview of some of the improvements we’ve made to this edition based

on student input:

Guiding Principles System

NEW!

Students can easily locate the information they need to master course concepts with the

new “Guiding Principles System (GPS).” At the beginning of every chapter, this innovative system plots a course through the chapter content by displaying the chapter

objectives, major topics, and related Example Exercises. The GPS reference to the chapter “At a Glance” summary completes this proven system.

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

2

1

3

4

Describe managerial

accounting and the role

of managerial

accounting in a

business.

Describe and illustrate

the following costs:

1. direct and indirect

costs

2. direct materials, direct

labor, and factory

overhead costs

3. product and period

costs

Describe and

illustrate the

following statements

for a manufacturing

business:

1. balance sheet

2. statement of cost of

goods manufactured

3. income statement

Describe the uses of

managerial accounting

information.

Managerial

Accounting

Manufacturing

Operations: Costs

and Terminology

Financial Statements

for a Manufacturing

Business

Uses of Managerial

Accounting

Direct and

Indirect Costs

Balance Sheet for a

Manufacturing

Business

Differences Between

Managerial and

Financial Accounting

The Management

Accountant in the

Organization

Manufacturing

Costs

1-2

EE (page 10)

EE 1-3

(page 11)

EE 1-4

(page 13)

Managerial

Accounting in the

Management

Process

1-1

EE (page 6)

At a Glance

NEW!

Income Statement

for a Manufacturing

Company

1-5

EE (page 18)

Menu

Turn to pg 19

Written for Today’s Students

Designed for today’s students, the 10th edition has been extensively revised using an

innovative, high-impact writing style that emphasizes topics in a concise and clearly

written manner. Direct sentences, concise paragraphs, numbered lists, and step-by-step

calculations provide students with an easy-to-follow structure for learning accounting.

This is achieved without sacrificing content or rigor.

vii

Leading by Example

NEW!

Revised Coverage of Investments

A new chapter on investments and fair value accounting has been written to consolidate coverage of both dept and equity investments. The chapter also contains a conceptual discussion of fair value accounting and its increasing role in defining today’s

modern accounting methods.

NEW!

IFRS

No topic is on the minds of many accounting practitioners more than the possible

convergence of IFRS and GAAP. How accounting educators handle this emerging

reality is perhaps even more of a question going forward. In the financial chapters

found within this text, IFRS icons now exist in the margin to help highlight certain

areas where differences exist between these standards.

NEW!

Modern User-Friendly Design

Based on students’ testimonials of what they find most useful, this streamlined presentation includes a wealth of helpful resources without the clutter. To update the look of the

material, some exhibits use computerized spreadsheets to better reflect the changing environment of business. Visual learners will appreciate the generous number of exhibits and

illustrations used to convey concepts and procedures.

Exhibit 4

Retained

Earnings

Statement for

Merchandising

Business

NetSolutions

Retained Earnings Statement

For the Year Ended December 31, 2011

$128,800

Retained earnings, January 1, 2011

Net income for the year

Less dividends

Increase in retained earnings

Retained earnings, December 31, 2011

$75,400

18,000

57,400

$186,200

Journal

Date

Description

Page 25

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

2011

Jan.

viii

3

Cash

Sales

To record cash sales.

1,800

1,800

Leading by Example

Chapter Updates and Enhancements

The following includes some of the specific content changes that can be

found in Managerial Accounting, 10e.

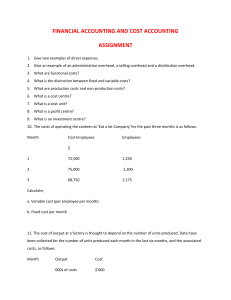

Chapter 1: Managerial Accounting Concepts

and Principles

• Added a new section at the beginning of the chapter on the uses of managerial

accounting, which references subsequent chapters where the uses are described and

illustrated.

• Added an illustration of comparing merchandising and manufacturing income

statements.

• Added format for the cost of goods manufactured statement.

• Added stepwise preparation of the cost of goods manufactured.

Chapter 2: Job Order Costing

• Added format for the entries used to dispose of overapplied or underapplied factory

overhead.

• Changed order of entries so that entries for sales and cost of goods sold are shown

separately from the finished goods entry for completed units.

Chapter 3: Process Cost Systems

• Revised Exhibit 2 and accompanying narrative so that Exhibit 2 ties into Exhibit 8,

which illustrates entries for Frozen Delights.

• Revised illustration of cost of production report so that units are classified into groups

consisting of beginning work in process units (Group 1), started and completed units

(Group 2), and ending work in process units (Group 3). This aids students in computing

unit costs and assigning costs to groups using first-in, first-out inventory cost flow.

Accompanying exhibits and art also classify units by these groups.

• Revised and expanded the section on using the cost of production report for decision

making to include an example from Frozen Delights.

Chapter 4: Cost Behavior and Cost-Volume-Profit

Analysis

• Supplemented the mixed cost discussion by adding an equation for determining

fixed costs.

• Added contribution margin equation to cost-volume-profit discussion.

• Added unit contribution margin equation to cost-volume-profit discussion.

• Added “change in income from operations” equation based on unit contribution

margin to cost-volume-profit discussion.

• Incorporated a discussion of computing break-even in sales dollars using contribution margin ratio.

• Added a stepwise approach to discussion of preparing cost-volume-profit and profit-volume charts.

• Added equation for computing the percent change in income from operations using

“operating leverage.”

• Expanded discussion of margin of safety so that margin of safety may be expressed

in sales dollars, units, or percent of current sales.

• Revised appendix on variable costing to include format for variable costing income

statement.

ix

Leading by Example

Chapter 5: Variable Costing for

Management Analysis

• Chapter objectives revised slightly.

• Generic absorption and variable costing income reporting formats illustrated in

Objective 1, followed by numerical examples.

• Graphic on page 184 revised to include units manufactured = units sold.

• Formulas (equations) added for contribution margin analysis section, Objective 5.

• Exhibits 11, 12, and 16 revised for clarity.

Chapter 6: Budgeting

•

•

•

•

Made minor changes to chapter objectives.

Added stepwise approach to preparing a flexible budget.

Modified the definition of the master budget.

Added new classifications of budget components of the master budget as operating,

investing, and financing budget components.

• Added format for determining “total units to be produced.”

• Added format for determining “direct materials to be purchased.”

Chapter 7: Performance Evaluation Using Variances

from Standard Costs

• Added a 2nd level heading for Objective 1, “Criticisms of Standard Costs.”

• Added several new headings for Objective 2, “Budget Performance Report” and

“Manufacturing Cost Variances.”

• Revised discussion of “Manufacturing Cost Variances” to better tie into subsequent

discussion of standard cost variances.

• Utilized a new equation format for computing standard cost variances. Using these

equations, a positive amount indicates an unfavorable variance while a negative

amount indicates a favorable variance. Later in the chapter, positive variance amounts

are recorded as debits and negative variance amounts are recorded as credits.

• Revised the factory overhead variance discussion to include equations for computing

total, variable, and fixed factory overhead rates. These rates are then used to explain

and illustrate the computation of the controllable factory overhead variance and the

volume factory overhead variance.

• Revised the factory overhead variance discussion to use equations for computing the

controllable and volume variances.

• Revised the discussion of how the total factory overhead cost variance is related to

overapplied or underapplied overhead balance. Further explanation is provided to

show how the overapplied or underapplied overhead balance can be separated into

the controllable and volume variances.

• Added new key terms for budgeted variable factory overhead, favorable cost variance, unfavorable cost variance, and standards.

Chapter 8: Performance Evaluation for Decentralized

Operations

• Modified the chapter objectives slightly.

• Added equations for computing service department charge rates.

• Presented equations for allocating service department charges to decentralized

operations (divisions).

x

Leading by Example

• Added example format for determining residual income.

• Added equations for computing increases and decreases in divisional income using

different negotiated transfer prices.

Chapter 9: Differential Analysis and Product Pricing

• Added section on managerial decision making. Objective 1 now includes a new flowchart depicting the steps that define the decision-making process.

• Added equations (e.g., markup percentages, desired profit) to “Setting Normal

Product Selling Prices” Section.

• Adopted a stepwise approach to setting normal prices for each cost-plus (total,

product, variable) concept.

• Added Exhibit 11 to summarize cost-plus approaches to setting normal prices.

• Added equation to determine “contribution margin per bottleneck constraint.”

• Presented equations for assessing product pricing and cost decisions related to bottlenecks.

• Added equation for determining “activity rate” in Activity-Based Costing appendix.

Chapter 10: Capital Investment Analysis

• Replaced XM Satellite Radio with Carnival Corporation as the opener vignette.

• Revised the learning objectives so that the nonpresent value (average rate of return

and cash payback) methods have a separate learning objective from the present value

(net present value and internal rate of return) methods.

• Added an equation for determining the “average investment” for use in the average

rate of return method.

• Added an equation for determining the “cash payback period.”

• Added a graphic for determining the present value of $1 along with additional explanations of present values.

• Added format for using the net present value method that is consistent with that

shown in the solutions manual.

• Added an equation for determining the present value index.

Chapter 11: Cost Allocation and Activity-Based Costing

• Added discussion and illustration of conditions when a single-plantwide rate might

cause product cost distortions.

• Added equations for determining activity rates.

Chapter 12: Cost Management for Just-in-Time

Environments

•

•

•

•

Chapter Objective 1 revised slightly.

Added equation for computing “Value-Added Ratio” for lead time.

Added equation for computing “Total Within-Batch Wait Time.”

Deleted Learning Objective 2 (Andersen Metal Fabricators" illustration) from previous edition.

• Moved discussion of JIT for nonmanufacturing setting to precede implications of JIT

for cost accounting.

xi

Leading by Example

Chapter 13: Statement of Cash Flows

• Revised beginning section discussing the statement of cash flows (SCF) and illustrating the format for the SCF under the direct and indirect methods.

• Revised beginning discussion of direct method to emphasize conversion of accrual

income statement to cash flows from operations (on an item-by-item basis). New

graphic for conversion of interest expense to cash payments for interest provides

visual reinforcement for this topic.

• Used stepwise format for preparing the statement of cash flows under indirect and

direct methods.

• Used stepwise format for preparing the work sheet for the indirect method in the end-ofchapter appendix.

Chapter 14: Financial Statement Analysis

• New chapter opener features Nike, Inc.

• Real world financial statement analysis problem features data from the Nike, Inc.

2007 10K, which can be found in Appendix B in the back of the text.

• Each ratio is highlighted in a boxed screen for easier review.

• Appendix on “Unusual Items on the Income Statement” was added.

xii

Leading by Example

Managerial Accounting, 10e, is unparalleled in pedagogical innovation. Our

constant dialogue with accounting faculty continues to affect how we refine

and improve the text to meet the needs of today’s students. Our goal is to

provide a logical framework and pedagogical system that caters to how students of today study and learn.

1

Describe and

illustrate reporting income from

operations under absorption and variable

costing.

EX 5-1

Inventory valuation

under absorption

costing and variable

costing

b. Inventory,

$294,840

Clear Objectives and Key Learning

Outcomes

To help guide students, the authors provide clear chapter objectives

and important learning outcomes. All aspects of the chapter materials relate back to these key points and outcomes, which keeps students focused on the most important topics and concepts in order to

succeed in the course.

At the end of the first year of operations, 5,200 units remained in the finished goods

inventory. The unit manufacturing costs during the year were as follows:

Direct materials

Direct labor

Fixed factory overhead

Variable factory overhead

$35.00

16.80

5.60

4.90

Determine the cost of the finished goods inventory reported on the balance sheet under

(a) the absorption costing concept and (b) the variable costing concept.

Example Exercises

Example Exercises were developed to reinforce concepts and procedures in a bold, new

way. Like a teacher in the classroom, students follow the authors’ example to see how to

complete accounting applications as they are presented in the text. This feature also provides a list of Practice Exercises that parallel the Example Exercises so students get the practice they need. In addition, the Practice Exercises also include references to the chapter

Example Exercises so that students can easily cross-reference when completing homework.

See the example of the

application being presented.

Follow along as

the authors

work through

the Example

Exercise.

Try these

corresponding

end-of-chapter

exercises for

practice!

Example Exercise 2-2

2

Direct Labor Costs

During March, Hatch Company accumulated 800 hours of direct labor costs on Job 101 and 600 hours

on Job 102. The total direct labor was incurred at a rate of $16 per direct labor hour for Job 101 and $12

per direct labor hour for Job 102. Journalize the entry to record the flow of labor costs into production

during March.

Follow My Example 2-2

Work in Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Wages Payable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

*Job 101

Job 102

Total

$12,800

7,200

_______

$20,000

_______

800 hrs.

600 hrs.

20,000*

20,000

$16

$12

For Practice: PE 2-2A, PE 2-2B

xiii

Leading by Example

“At a Glance” Chapter Summary

The “At a Glance” summary grid ties everything together and helps students stay on

track. First, the Key Points recap the chapter content for each chapter objective. Second,

the related Key Learning Outcomes list all of the expected student performance capabilities that come from completing each objective. In case students need further practice

on a specific outcome, the last two columns reference related Example Exercises and

their corresponding Practice Exercises. In addition, the “At a Glance” grid guides struggling students from the assignable Practice Exercises to the resources in the chapter that

will help them complete their homework. Through this intuitive grid, all of the chapter

pedagogy links together in one cleanly integrated summary.

2

Prepare a cost of production report.

Key Points

Example

Exercises

Practice

Exercises

• Determine the whole units

charged to production and to be

assigned costs.

3-2

3-2A, 3-2B

• Compute the equivalent units

with respect to materials.

3-3

3-3A, 3-3B

• Compute the equivalent units

with respect to conversion.

3-4

3-4A, 3-4B

• Compute the costs per

equivalent unit.

3-5

3-5A, 3-5B

• Allocate the costs to beginning

inventory, units started and

completed, and ending

inventory.

3-6

3-6A, 3-6B

Key Learning Outcomes

Manufacturing costs must be allocated

between the units that have been completed

and those that remain within the department.

This allocation is accomplished by allocating

costs using equivalent units of production during

the period for the beginning inventory, units

started and completed, and the ending

inventory.

• Prepare a cost of production

report.

Provides a conceptual

review of each

objective.

Creates a checklist of

skills to help review for

a test.

Real-World Chapter

Openers

xiv

H

A

P

T

E

R

2

Job Order Costing

©2006 James Goulden/AAAphotos.org—All Rights Reserved

Building on the strengths of past editions,

these openers continue to relate the

accounting and business concepts in the

chapter to students’ lives. These openers

employ examples of real companies and

provide invaluable insight into real practice.

Several of the openers created especially for

this edition focus on interesting companies

such as Washburn Guitars, The North Face,

and Netflix.

C

Directs the student

to this helpful

feature!

D A N

A

D O N E G A N ’ S

s we discussed in Chapter 1, Dan Donegan of the

rock band Disturbed uses a custom-made guitar purchased from Washburn Guitars. In fact, Dan Donegan designed his guitar in partnership with Washburn Guitars,

which contributed to Washburn’s Maya Series of guitars.

The Maya guitar is a precision instrument that amateurs

and professionals are willing to pay between $1,400 and

$7,000 to own. In order for Washburn to stay in business,

the purchase price of the guitar must be greater than the

cost of producing the guitar. So, how does Washburn determine the cost of producing a guitar?

Costs associated with creating a guitar include materials such as wood and strings, the wages of employees who

build the guitar, and factory overhead. To determine the

G U I T A R

purchase price of Dan’s Maya, Washburn identifies and

records the costs that go into the guitar during each step

of the manufacturing process. As the guitar moves through

the production process, the costs of direct materials, direct

labor, and factory overhead are recorded. When

the guitar is complete, the costs that have been

recorded are added up to determine the cost of

Dan’s unique Maya Series guitar. The company

then prices the guitar to achieve a level of profit

over the cost of the guitar. This chapter introduces the principles of accounting systems that

accumulate costs in the same manner as they

were for Dan Donegan’s guitar.

Leading by Example

Business Connection and Comprehensive

Real-World Notes

Students get a close-up look at how accounting operates in the marketplace through a

variety of items in the margins and in the “Business Connection” boxed features. In addition, a variety of end-ofchapter exercises and

problems employ reallargest business, such as Ford Motor Company, compaTHE ACCOUNTING EQUATION

nies use the accounting equation. Some examples taken

world data to give stuThe accounting equation serves as the basic foundation for from recent financial reports of well-known companies are

the accounting systems of all companies. From the small- shown below.

dents a feel for the materiest business, such as the local convenience store, to the

al that accountants see

Company

Assets*

Liabilities

Owner’s Equity

daily. No matter where

$13,043

$16,920

The Coca-Cola Company

$ 29,963

Circuit City Stores, Inc.

4,007

2,216

1,791

they are found, elements

Dell Inc.

25,635

21,196

4,439

2,589

10,905

eBay Inc.

13,494

that use material from real

1,433

17,040

Google

18,473

McDonald’s

29,024

13,566

15,458

companies are indicated

32,074

31,097

Microsoft Corporation

63,171

Southwest Airlines Co.

13,460

7,011

6,449

with a unique icon for a

Wal-Mart

151,193

89,620

61,573

consistent presentation.

*Amounts are shown in millions of dollars.

Integrity, Objectivity, and Ethics in Business

In each chapter, these cases help students develop their ethical compass. Often coupled

with related end-of-chapter activities, these cases can be discussed in class or students

can consider the cases as they read the chapter. Both the section and related end-ofchapter materials are indicated with a unique icon for a consistent presentation.

ACCOUNTING REFORM

The financial accounting and reporting failures of Enron,

WorldCom, Tyco, Xerox, and others shocked the investing public. The disclosure that some of the nation’s largest and best-known corporations had overstated profits

and misled investors raised the question: Where were the

CPAs?

In response, Congress passed the Investor Protection,

Auditor Reform, and Transparency Act of 2002, called the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The Act establishes a Public Company

Accounting Oversight Board to regulate the portion of the

accounting profession that has public companies as clients.

In addition, the Act prohibits auditors (CPAs) from providing certain types of nonaudit services, such as investment

banking or legal services, to their clients, prohibits employment of auditors by clients for one year after they

last audited the client, and increases penalties for the

reporting of misleading financial statements.

xv

Leading by Example

Summaries

Within each chapter, these synopses draw special attention to important points and

help clarify difficult concepts.

Self-Examination Questions

Five multiple-choice questions, with answers at the end of the chapter, help students

review and retain chapter concepts.

Illustrative Problem and Solution

A solved problem models one or more of the chapter’s assignment problems so that students can apply the modeled procedures to end-of-chapter materials.

Market Leading End-of-Chapter Material

Students need to practice accounting so that they can understand and use it. To give

students the greatest possible advantage in the real world, Managerial Accounting, 10e,

goes beyond presenting theory and procedure with comprehensive, time-tested, endof-chapter material.

xvi

Online Solutions

South-Western, a division of Cengage Learning, offers a vast array of

online solutions to suit your course needs. Choose the product that best

meets your classroom needs and course goals. Please check with your

Cengage representative for more details or for ordering information.

Aplia

Founded in 2000 by economist and Stanford professor Paul Romer, Aplia is an educational technology company dedicated to improving learning by increasing student

effort and engagement. Currently, our products support college-level courses and have

been used by more than 650,000 students at over 750 institutions.

For students, Aplia offers a way to stay on top of coursework with regularly scheduled homework assignments. Interactive tools and content further increase engagement

and understanding.

For professors, Aplia offers high-quality, auto-graded assignments, which ensure

that students put forth effort on a regular basis throughout the term. These assignments

have been developed for a range of textbooks and are easily customized for individual

teaching schedules.

Every day, we develop our

products by responding to the

needs and concerns of the students

and professors who use Aplia in

their classrooms. As you explore

the features and benefits Aplia has

to offer, we hope to hear from you

as well.

Welcome to Aplia.

CengageNOW Express

CengageNOW Express™ for Warren/Reeve/Duchac Managerial Accounting,

10e, is an online homework solution that delivers better student outcomes—NOW!

CengageNOW Express focuses on the textbook homework that is central to success in

accounting with streamlined course start-up, straightforward assignment creation,

automatic grading and tracking student progress, and instant feedback for students.

• Streamlined Course Start-Up: All Brief Exercises, Exercises, Problems, and

Comprehensive Problems are available immediately for students to practice.

• Straightforward Assignment Creation: Select required exercises and problems, and

CengageNOW Express automatically applies faculty approved, Accounting

Homework Options.

• Automatic grading and tracking student progress: CengageNOW Express grades and

captures students’ scores to easily monitor their progress. Export the grade book to

Excel for easy data management.

• Instant feedback for students: Students stay on track with instructor-written hints

and immediate feedback with every assignment. Links to the e-book, animated exercise demonstrations, and Excel spreadsheets from specific assignments are ideal for

student review.

xvii

Online Solutions

CengageNOW

CengageNOW for Warren/Reeve/Duchac Managerial Accounting, 10e, is

a powerful and fully integrated online teaching and learning system that provides you

with flexibility and control. This complete digital solution offers a comprehensive set of

digital tools to power your course. CengageNOW offers the following:

• Homework, including algorithmic variations

• Integrated E-book

• Personalized Study Plans, which include a variety of multimedia assets (from

exercise demonstrations to video to iPod content) for students as they master the

chapter materials

• Assessment options which include the full test bank, including algorithmic

variations

• Reporting capability based on AACSB, AICPA, and IMA competencies and standards

• Course Management tools, including grade book

• WebCT and Blackboard Integration

WebTutor™!

Available packaged with Warren/Reeve/Duchac Managerial Accounting,

10e, or for individual student purchase Jumpstart your course with customizable, rich, text-specific content within your Course Management System.

• Jumpstart—Simply load a WebTutor cartridge into your Course Management System.

• Customizable—Easily blend, add, edit, reorganize, or delete content.

• Content—Rich, text-specific content, media assets, quizzing, test bank, weblinks, discussion topics, interactive games and exercises, and more.

Visit www.cengage.com for more information.

xviii

For the Instructor

When it comes to supporting instructors, South-Western is unsurpassed.

Managerial Accounting, 10e, continues the tradition with powerful print and

digital ancillaries aimed at facilitating greater course successes.

Instructor’s Manual This manual contains a number of resources designed to aid

instructors as they prepare lectures, assign homework, and teach in the classroom. For each

chapter, the instructor is given a brief synopsis and a list of objectives. Then each objective

is explored, including information on Key Terms, Ideas for Class Discussion, Lecture Aids,

Demonstration Problems, Group Learning Activities, Exercises and Problems for

Reinforcement, and Internet Activities. Also, Suggested Approaches are included that incorporate many of the teaching initiatives being stressed in higher education today, including

active learning, collaborative learning, critical thinking, and writing across the curriculum.

Solutions Manual The Solutions Manual contains answers to all exercises, problems,

and activities that appear in the text. As always, the solutions are author-written and

verified multiple times for numerical accuracy and consistency with the core text.

Solutions transparencies are also available.

Test Bank For each chapter, the Test Bank includes True/False questions, MultipleChoice questions, and Problems, each marked with a difficulty level, chapter objective

association, and a tie-in to standard course outcomes. Along with the normal update

and upgrade of the 2,800 test bank questions, variations of the new Example Exercises

have been added to this bank for further quizzing and better integration with the textbook. In addition, the bank provides a grid for each chapter that compiles the correlation of each question to the individual chapter’s objectives, as well as a ranking of difficulty based on a clearly described categorization. Through this helpful grid, making a

test that is comprehensive and well-balanced is a snap!

ExamView® Pro Testing Software This intuitive software allows you to easily customize exams, practice tests, and tutorials and deliver them over a network, on the

Internet, or in printed form. In addition, ExamView comes with searching capabilities

that make sorting the wealth of questions from the printed test bank easy. The software

and files are found on the IRCD.

PowerPoint® Each presentation, which is included on the IRCD and on the product

support site, enhances lectures and simplifies class preparation. Each chapter contains

objectives followed by a thorough outline of the chapter that easily provide an entire

lecture model. Also, exhibits from the chapter, such as the new Example Exercises, have

been recreated as colorful PowerPoint slides to create a powerful, customizable tool.

Instructor Excel® Templates These templates provide the solutions for the problems and exercises that have Enhanced Excel® templates for students. Through these

files, instructors can see the solutions in the same format as the students. All problems

with accompanying templates are marked in the book with an icon and are listed in the

information grid in the solutions manual. These templates are available for download

on www.cengage.com/accounting/warren or on the IRCD.

Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM This convenient resource includes the PowerPoint®

Presentations, Instructor’s Manual, Solutions Manual, Test Bank, ExamView®, An

Instructor’s Guide to Online Resources, and Excel Application Solutions. Lively demonstrations of support technology are also included. All the basic material an instructor

would need is available in one place on this IRCD.

xix

For the Student

Students come to accounting with a variety of learning needs. Managerial

Accounting, 10e, offers a broad range of supplements in both printed form

and easy-to-use technology. We continue to refine our entire supplement

package around the comments instructors have provided about their

courses and teaching needs.

Study Guide This author-written guide provides students Quiz and Test Hints,

Matching questions, Fill-in-the-Blank questions (Parts A & B), Multiple-Choice questions, True/False questions, Exercises, and Problems for each chapter. Designed to

assist students in comprehending the concepts and principles in the text, solutions for

all of these items are available in the guide for quick reference.

Working Papers for Exercises and Problems The traditional working papers

include problem-specific forms for preparing solutions for Exercises, A & B Problems,

the Continuing Problem, and the Comprehensive Problems from the textbook. These

forms, with preprinted headings, provide a structure for the problems, which helps

students get started and saves them time. Additional blank forms are included.

Blank Working Papers These Working Papers are available for completing exercises and problems either from the text or prepared by the instructor. They have no

preprinted headings. A guide at the front of the Working Papers tells students which

form they will need for each problem.

Enhanced Excel® Templates These templates are provided for selected long or

complicated end-of-chapter exercises and problems and provide assistance to the

student as they set up and work the problem. Certain cells are coded to display a red

asterisk when an incorrect answer is entered, which helps students stay on track.

Selected problems that can be solved using these templates are designated by an icon.

Klooster & Allen General Ledger Software Prepared by Dale Klooster and

Warren Allen, this best-selling, educational, general ledger package introduces students

to the world of computerized accounting through a more intuitive, user-friendly system

than the commercial software they’ll use in the future. In addition, students have access

to general ledger files with information based on problems from the textbook and practice sets. The program is enhanced with a problem checker that enables students to

determine if their entries are correct and emulates commercial general ledger packages

more closely than other educational packages. Problems that can be used with

Klooster/Allen are highlighted by an icon. A free Network Version is available to

schools whose students purchase Klooster/Allen GL.

Product Support Web Site www.cengage.com/accounting/warren. This site provides students with a wealth of introductory accounting resources, including quizzing

and supplement downloads and access to the Enhanced Excel® Templates.

xx

Acknowledgments

Many of the enhancements made to Managerial Accounting, 10e, are a direct result of countless conversations we’ve had with principles of accounting students over the past several years. We want to take

this opportunity to thank them for their perspectives and feedback on textbook use; we think that 10e

represents our finest edition yet!

Bucks County Community

College

Instructors: Lori Grady,

Judy Toland

Bernadette Allen

Matarazzo

Vikas Patel

Erica Olsen

Eric Goldner

Shelly Rushbrook

Eamon Coleman

Tracy Bunsick

Baltimore City Community

College

Instructors: Jeff Hillard,

John Wiley

Sulaimon Adeyemi

Udeya Diour

Dwain White

Debra Witherspoon

Jacqueline Tuggle

Mabono Soumahoo

Des Moines Area

Community College

Instructors: Shea Mears,

Patty Holmes

Zach Schmidt

Angie Lee

Tim Hoffman

Richard Palmer

Sharon Beattie

Joseph J. Johnson

Armina Kahrimanovic

Ryan Wisnousky

Lindsay Tripp

Tiffany Shuey

Jenny Leonard

Susann Shaffner

Cori Shanahan

Nicholas Wallace

Kyle Melohn

Wendy Doolittle

LaRue Brannan

Nicholas Christopher

Yaeger

Jason Aitchison

Kean University

Instructor: Gary Schader

Margherita Marjotta

Hugo Prado

Marta Domanska

Nicole Foy

Andrea Colbert

Khatija Bibi

Houston Community

College

Instructor: Linda

Flowers

Yildirim Kocoglu

Ana Zelaya

Seungkyu Kim

Mohammad Arsallan

Bakali

Vanessa K. Rangel

Cher Lay

Sherika Gibson

Ulsi Ramos

Muhammad Shaikha

Hong Yang

Pamela Ruiz

Yvonne Ngo

Lansing Community

College

Instructor: Patricia

Walczak

Ana Topor

John Barrett

Brandon Smithwick

Bradley L. Moore

Cassandra DeVos

Elizabeth C. Escalera

Clara Powers

Lance Spencer

Jennifer Jones

Aristoteles Paiva Lopes

Oakland Community

College

Instructor: Deborah

Niemer

Paul Boker

Tracie M. Leitner

Thetnia Lynette Cobb

Vera Kolaj

Olivia Burke

Thomas J. Zuchowski

Ryan Shead

Austen Michaels

Michaele Jones

Bradlee J. VanAlstine

Tim Doherty

Vanya Jelezarova

Nilda Dervishaj

Maja Lulgjuraj

Pierce Radtke

Butler Community

College

Instructors: Jennifer

Brewer, Janice Akao

Sarah Kirkwood

Kimberly Brothers

Christine Brown

Chelsey Perkins

Thomas Mackay

Tucker Stewart

Austin Birkholtz

Santa Monica College

Instructors: Greg Brookins,

Terri Bernstein, and Pat

Halliday

Julieta Loreto

Noah Johnson

Matthew Nyby

Anitha Guna Wijaya

Jovani Rodriguez

Michelle Sharma

Marisol Granele

Prashila Sharma

Karlie Bryant

Wing San Kwong

Anthony Mitchell

Metropolitan Community

College

Instructor: Idalene

Williams

Suquett Saunders

Danette Cook

Ewokem Akohachere

Ivina Washington

Queen Esther Tucker

Jamie Rusch

Daisuke Motomura

Comlanri S. Zannou

Melissa Brunious

Marc Anderson

Keith Costello

Robyn Adler

Kelly Fitzgerald

Volunteer State

Community College

Instructor: Brent

Trentham

Kris Anderson

Jasmine Cox

Wendy Nabors

Patrick Farmer

Justin Gill

Kathryn Gambrell

Dana Mihalko

Kavitha Sudheendra

April Jeffries

Ray Mefford

Ashlee Kilpatrick

Cedar Valley

Instructor: S.T. Desai

Tiffany King

Kareem Aziz

Ebony Wingard

Cheryl Boyd

Dwevelyn Jennings

Kal Takieddin

Lazari Vanly

Adrian McKinney

Tanya Hubbard

Angela Fulbright

Tenisha Blair

Jamie Riley

Roshunda Webb

Porsha Espie

Keisha Murrell

Dawn Smith

Sinclair Community College

Instructor: Donna

Chadwick

Emanuel Gena

Victoria Wiseman

Daniel Hulet

Naaman Beck

Eric Pedro

Kathy Ernest

Jessica Weiss

Jessica Baker

Champer Murtery

Steve Huffman

Regis Allison

Hiba Ligawad

Cara Scott

Tammy Baughman

Kevin Ricketts

Nora Hatlab

Mary Kasper

Nicole Sutherland,

Grossmont College

Katie Longo, Southern

Adventist University

Joel Hughes, Southern

Adventist University

Lisa Hubbard, Mid-State

Technical College

Amanda Baker,

Davenport University

Phillipe Bouzy, Southern

Adventist University

Barbara Bryant, DeKalb

Technical College

Charisse Dolina,

Maharishi School of

Management

Amanda Worrell,

Southern Adventist

University

Angela Snider, Cardinal

Stritch University

Star Maddox, DeKalb

Technical College

Charles Balliet, Lehigh

Carbon CC

Ashley Heath, Buena

Vista University

Brianna Miller, Southern

Adventist University

John Varga,

Orange Coast College

Roger Montero, East

Los Angeles College

Terry Thorpe,

Irvine Valley

Jim Sugden,

Orange Coast College

WebEx Focus Group

Participants

April Wakefield,

Northcentral Technical

College

xxi

The following instructors

are members of our Blue

Sky editorial board,

whose helpful comments

and feedback continue to

have a profound impact

on the presentation and

core themes of this text:

Ana M. Cruz

Miami Dade College

Gloria Worthy

Southwest Tennessee

Community College

Walter DeAguero

Saddleback College

Lee Smart

Southwest Tennessee

Community College

Rick Andrews

Sinclair Community College

Donna Chadwick

Sinclair Community

College

Warren Smock

Ivy Tech Community College

Terry Dancer

Arkansas State University

David L. Davis

Tallahassee Community

College

Robert Dunlevy

Montgomery County

Community College

Richard Ellison

Middlesex County College

W. Michael Fagan

Raritan Valley Community

College

Carol Flowers

Orange Coast College

Shirly A. Kleiner

Johnson County

Community College

Carol Welsh

Rowan University

Patrick Borja

Citrus College

Michael M. Landers

Middlesex College

Chris Widmer

Tidewater Community

College

Robert Adkins

Clark State Community

College

Phillip Lee

Nashville State

Community College

Lynnette Mayne Yerbury

Salt Lake Community

College

Melvin Williams

College of the Mainland

Denise Leggett

Middle Tennessee State

University

The following instructors have participated in

the review process,

focus groups, and marketing events for this

new edition:

Patrick Rogan

Consumes River

College

Lynne Luper

Ocean County College

Maria C. Mari

Miami Dade College

Thomas S. Marsh

Northern Virginia

Community College—

Annandale

Cynthia McCall

Des Moines Area

Community College

Gary Schader

Kean University

Linda S. Flowers

Houston Community

College

Priscilla Wisner

Montana State University

Mike Foland

Southwest Illinois College

Andrea Murowski

Brookdale Community

College

Audrey Hunter

Broward Community College

Anthony Fortini

Camden Community College

Rachel Pernia

Essex County College

Renee Rigoni

Monroe Community College

Terry Thorpe

Irvine Community College

Patricia Walczak

Lansing Community College

Judith Zander

Grossmont College

Gilda M. Agacer

Monmouth University

Irene C. Bembenista

Davenport University

Laurel L. Berry

Bryant & Stratton College

Bill Black

Raritan Valley Community

College

Gregory Brookins

Santa Monica College

Barbara M. Gershowitz

Nashville State

Community College

Angelina Gincel

Middlesex County College

Lori Grady

Bucks County Community

College

Joseph R. Guardino

Kingsborough Community

College

Amy F. Haas

Kingsborough Community

College

Betty Habershon

Prince George’s

Community College

Patrick A. Haggerty

Lansing Community

College

Rebecca Carr

Arkansas State University

Becky Hancock

El Paso Community

College

James L. Cieslak

Cuyahoga Community

College

Paul Harris

Camden County College

Sue Cook

Tulsa Community College

xxii

Patricia H. Holmes

Des Moines Area

Community College

Brenda Fowler

Alamance Community

College

James Cieslaks

Cuyahoga Community

College

Shelia Ammons

Austin Community College

Felicia Baldwin

Daley College

Peggy Smith

Baker College—Auburn

Hills

Debra Kiss

Davenport University

Christopher Mayer

Bergen Community

College

Dawn Peters

Southwest Illinois College

Gary J. Pieroni

Diablo Valley College

Audrey Hunter

Broward Community College

Debra Prendergast

Northwestern Business

College

Cathy Montesarchio

Broward Community

College

Eric Rothernburg

Kingsborough Community

College

Richard Sarkisian

Camden Community College

Gerald Savage

Essex Community College

Janice Stoudemire

Midlands Technical

College

Linda H. Tarrago

Hillsborough Community

College

Lawrence Roman

Cuyahoga Community

College

Darlene B. Lindsey

Hinds Community College

Michelle Grant

Bossier Parish Community

College

Lou Rosamillia

Hudson Valley Community

College

Sandee Cohen

Columbia College—Chicago

Laurel L. Berry

Bryant and Stratton

College

Judy Toland

Bucks County Community

College

Lori Grady

Bucks County Community

College

Rafik Elias

California State University

—Los Angeles

Norris Dorsey

California State University

—Northridge

Judy Toland

Buck Community College

Angela Siedel

Cambria-Rowe Business

College

Bob Urell

Irvine Valley College

Suryakant Desai

Cedar Valley College

Marilyn Ciolino

Delgado Community

College

Patti Holmes

Des Moines Area

Community College

Gary J. Pieroni

Diablo Valley College

Rebecca Brown

DMACC—Carroll Campus

Chris Gilbert

East Los Angeles College

Satoshi K. Kojima

East Los Angeles College

Ron Ozur

East Los Angeles College

Lorenzo Ybarra

East Los Angeles College

Carol Dutchover

Eastern New Mexico

University—Roswell

Peter VanderWeyst

Edmonds Community

College

Debbie Luna

El Paso Community

College

Lee Cannell

El Paso Community

College

Kenneth O’Brien

Farmingdale State College

Lynn Clements

Florida Southern College

Sara Seyedin

Foothill College

Aaron Reeves

Forest Park Community

College

Ron Dustin

Fresno City College

Christy Kloezman

Glendale Community

College

Scott Stroher

Glendale Community

College

Brenda Bindschatel

Green River Community

College

Judith Zander

Grossmont College

Susan Logorda

Lehigh Carbon Community

College

Kirk Canzano

Long Beach City College

Frank Iazzetta

Long Beach City College

Anothony Dellarte

Luzerne County Community

College

Bruce England

Massasoit Community

College

Idalene Williams

Metropolitan Community

College

Cathy Larson

Middlesex Community

College

Janice Stoudemire

Midlands Technical

College

Dick Ahrens

Pierce College

Catherine Jeppson

Pierce College

Al Partington

Pierce College

Mercedes Martinez

Rio Hondo College

Michael Chaks

Riverside Community

College

Cheryl Honore

Riverside Community

College

Frank Stearns

Riverside Community

College

Patricia Worsham

Riverside Community

College

Leonard Cronin

Rochester Community

College

Dominque Svarc

Harper College

Renee Rigoni

Monroe Community

College

Jennifer Finley

Hill College

Janice Feingold

Moorpark College

Michelle Powell Dancy

Holmes Community

College

Yaw Mensah

Rutgers University

Patricia Feller

Nashville State

Community College

Terry Thorpe

Irvine Community College

David Juriga

Saint Louis Community

College

Ray Wurzburger

New River Community

College

Doug Larson

Salem State College

Leslie Thysell

John Tyler Community

College

Desta Damtew

Norfolk State University

Carol Welsh

Rowan University

David L. Davis

Tallahassee Community

College

Chris Widmer

Tidewater Community

College

Julie Gilbert

Triton College

Stephanie Farewell

U of Arkansas—

Little Rock

Sanford Kahn

University of Cincinnati

Suzanne McCaffrey

University of

Mississippi

Pete Rector

Victor Valley College

Daniel Gibbons

Waubonsee Community

College

The following instructors created content for

the supplements that

accompany the text:

Christine Jonick

Gainesville State College

CengageNOW

Janice Stoudemire

Midlands Technical

College

CengageNOW

Greg Brookins

Santa Monica College

Angie LaTourneau

Winthrop University

CengageNOW

Dan King

Shoreline Community

College

Ann Martel

Marquette University

CengageNOW

Ann Gregory

South Plains College

Robin Turner

Rowan-Cabarrus

Community College

CengageNOW

Shirly A. Kleiner

Johnson County

Community College

Andrew McKee

North Country Community

College

Alex Clifford

Kennebec Valley Technical

College

Greg Lauer

North Iowa Area

Community College

Eric Rothenburg

Kingsborough Community

College

Debra Prendergast

Northwestern Business

College

John Dudley

La Harbor College

Lynne Luper

Ocean County College

Abdul Qastin

Lakeland College

Audrey Morrison

Pensacola Junior College

John Teter

St. Petersburg

College

Patricia Walczak

Lansing Community

College

Judy Grotrian

Peru State College

Bonnie Scrogham

Sullivan University

Gloria Worthy

Southwest Tennessee

Community College

Beatrice Garcia

Southwest Texas Junior

College

Sheila Ammons

Austin Community College

CengageNOW

Tracie Nobles

Austin Community College

CengageNOW

Patti Lopez

Valencia Community

College

General Ledger Software

LuAnn Bean

Florida Institute of

Technology

Test Bank

Barbara Durham

University of Central

Florida

Test Bank

Doug Cloud

Pepperdine University

PowerPoint Presentations

Kirk Lynch

Sandhills Community

College

Instructor’s Manual

Lori Grady

Bucks County Community

College

JoinIN/Turning Point

Kevin McFarlane

Front Range Community

College

Achievement Tests, Web

Quizzes

L.L. Price

Pierce College

Leaping Lizards Lawn Care

Practice Set

Don Lucy

Indian River Community

College

Bath Designs, Danielle’s

Dog Care Practice Sets

Jose Luis Hortensi

Miami Dade College

Fitness City Merchandise

Practice Set

Edward Krohn,

Miami Dade, College

Star Computer Sales and

Services Practice Set

Ana Cruz & Blanca Ortega,

Miami Dade College

Artistic Décor Practice Set

Craig Pence

Highland Community

College

Spreadsheets

xxiii

This page intentionally left blank

BRIEF CONTENTS

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

A

B

Managerial Accounting Concepts and Principles. . . . . . . . . . . 1

Job Order Costing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Process Cost Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Cost Behavior and Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis. . . . . . . . . . 131

Variable Costing for Management Analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

Budgeting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227

Performance Evaluation Using Variances from

Standard Costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273

Performance Evaluation for Decentralized Operations . . . . . . 317

Differential Analysis and Product Pricing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 361

Capital Investment Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 405

Cost Allocation and Activity-Based Costing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 443

Cost Management for Just-in-Time Environments. . . . . . . . . 489

Statement of Cash Flows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 529

Financial Statement Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 583

Interest Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Form 10-K Nike Inc. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Subject Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Company Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A-2

B-1

G-1

I-1

I-12

xxv

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

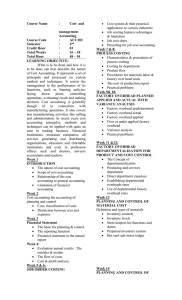

CHAPTER

1

Managerial Accounting Concepts

and Principles 1

Managerial Accounting 2

Differences Between Managerial and Financial Accounting 3

The Management Accountant in the Organization 4

Managerial Accounting in the Management Process 5

Manufacturing Operations: Costs and Terminology 7

Direct and Indirect Costs 8

Manufacturing Costs 9

Financial Statements for A Manufacturing Business 13

Balance Sheet for a Manufacturing Business 13

Income Statement for a Manufacturing Company 14

Uses of Managerial Accounting 16

Business Connection: Navigating The Information

Highway 19

CHAPTER

2

Job Order Costing 38

Cost Accounting System Overview 39

Job Order Cost Systems for Manufacturing Businesses 40

Materials 41

Factory Labor 43

Factory Overhead Cost 45

Work in Process 50

Finished Goods 51

Sales and Cost of Goods Sold 52

Period Costs 52

Summary of Cost Flows for Legend Guitars 52

Job Order Costing for Decision Making 54

Job Order Cost Systems for Professional Service

Businesses 55

Business Connection: Making Money in the Movie

Business 56

Step 4: Allocate Costs to Units Transferred Out and Partially

Completed Units 94

Preparing the Cost of Production Report 96

Journal Entries for a Process Cost System 97

Using the Cost of Production Report for Decision

Making 100

Frozen Delight 100

Holland Beverage Company 101

Yield 101

Just-in-Time Processing 102

Business Connection: Radical Improvement: Just in Time for

Pulaski’s Customers 104

Appendix: Average Cost Method 104

Determining Costs Using the Average Cost Method 104

The Cost of Production Report 106

CHAPTER

4

Cost Behavior and Cost-VolumeProfit Analysis 131

Cost Behavior 132

Variable Costs 133

Fixed Costs 134

Mixed Costs 134

Summary of Cost Behavior Concepts 137

Cost-Volume-Profit Relationships 137

Contribution Margin 138

Contribution Margin Ratio 138

Unit Contribution Margin 139

Mathematical Approach to Cost-Volume-Profit

Analysis 141

Break-Even Point 141

Business Connection: Breaking Even on Howard

Stern 144

Target Profit 144

Graphic Approach to Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis 146

CHAPTER

3

Process Cost Systems 80

Process Cost Systems 81

Comparing Job Order and Process Cost Systems 82

Cost Flows for a Process Manufacturer 84

Cost of Production Report 87

Step 1: Determine the Units to Be Assigned Costs 87

Step 2: Compute Equivalent Units of Production 89

Step 3: Determine the Cost per Equivalent Unit 92

Cost-Volume-Profit (Break-Even) Chart 146

Profit-Volume Chart 148

Use of Computers in Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis 149

Assumptions of Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis 149

Special Cost-Volume-Profit Relationships 150

Sales Mix Considerations 151

Operating Leverage 152

Margin of Safety 154

xxvii

CHAPTER

5

Variable Costing for Management

Analysis 177

Income From Operations Under Absorption Costing and

Variable Costing 178

Absorption Costing 178

Variable Costing 179

Units Manufactured Equal Unit Sold 181

Units Manufactured Exceed Units Sold 181

Units Manufactured Less Than Units Sold 182

Effects on Income from Operations 184

Income Analysis Under Absorption and Variable Costing 185

Using Absorption and Variable Costing 188

Controlling Costs 188

Pricing Products 189

Planning Production 189

Analyzing Contribution Margins 189

Analyzing Market Segments 189

Analyzing Market Segments 189

Sales Territory Profitability Analysis 190

Product Profitability Analysis 191

Salesperson Profitability Analysis 192

Business Connection: McDonald’s Corporation Contribution

Margin by Store 193

Contribution Margin Analysis 194

Variable Costing for Service Firms 196

Reporting Income from Operations Using Variable Costing for

a Service Company 196

Market Segment Analysis for Service Company 197

Contribution Margin Analysis 198

CHAPTER

6

7

Performance Evaluation Using

Variances from Standard Costs 273

Standards 274

Setting Standards 275

Types of Standards 275

Reviewing and Revising Standards 276

Criticisms of Standard Costs 276

Business Connection: Making the Grade in the Real World—

The 360-Degree Review 276

Budgetary Performance Evaluation 277

Budget Performance Report 278

Manufacturing Cost Variances 279

Direct Materials and Direct Labor Variances 280

Direct Materials Variances 280

Direct Labor Variances 282

Factory Overhead Variances 285

The Factory Overhead Flexile Budget 285

Variable Factory Overhead Controllable Variance 286

Fixed Factory Overhead Volume Variance 287

Reporting Factory Overhead Variances 289

Factory Overhead Account 289

Recording and Reporting Variances from Standards 291

Nonfinancial Performance Measures 294

Comprehensive Problem 1 312

CHAPTER

8

Performance Evaluation for

Decentralized Operations 317

Centralized and Decentralized Operations 318

Budgeting 227

Nature and Objectives Of Budgeting 228

Objectives of Budgeting 229

Human Behavior and Budgeting 229

Budgeting Systems 231

Static Budget 232

Flexile Budget 232

Business Connection: Build Versus Harvest 233

Computerized Budgeting Systems 234

Master Budget 235

Income Statement Budgets 236

Sales Budget 236

Production Budget 237

Direct Materials Purchases Budget 238

Direct Labor Cost Budget 239

Factory Overhead Cost Budget 240

Cost of Goods Sold Budget 241

Selling and Administrative Expenses Budget 243

Budgeted Income Statement 243

Balance Sheet Budgets 243

Cash Budget 244

Capital Expenditures Budget 247

Budgeted Balance Sheet 248

xxviii

CHAPTER

Advantages of Decentralization 319

Disadvantages of Decentralization 319

Responsibility Accounting 319

Responsibility Accounting for Cost Centers 320

Responsibility Accounting for Profit Centers 322

Service Department Charges 322

Profit Center Reporting 325

Responsibility Accounting for Investment Centers 326

Rate of Return on Investment 327

Business Connection: Return on Investment 330

Residual Income 330

The Balanced Scorecard 332

Transfer Pricing 333

Market Price Approach 334

Negotiated Price Approach 335

Cost Price Approach 337

CHAPTER

9

Differential Analysis and Product

Pricing 361

Differential Analysis 362

Lease or Sell 364

Discontinue a Segment or Product 365

Make or Buy 367

Replace Equipment 369

Process or Sell 370

Accept Business at a Special Price 371

Setting Normal Product Selling Prices 373

Total Cost Concept 373

Product Cost Concept 376

Variable Cost Concept 377

Choosing a Cost-Plus Approach Cost Concept 379

Activity-Based Costing 380

Target Costing 380

Production Bottlenecks, Pricing, and Profits 381

Production Bottlenecks and Profits 381

Production Bottlenecks and Pricing 382

Business Connection: What Is a Product? 383

CHAPTER

10

Capital Investment Analysis 405

Nature of Capital Investment Analysis 406

Methods Not Using Present Values 407

Average Rate of Return Method 407

Cash Payback Method 408

Methods Using Present Values 410

Present Value Concepts 410

Net Present Value Method 413

Internal Rate of Return Method 415

Business Connection: Panera Bread Store Rate of Return 417

Factors That Complicate Capital Investment Analysis 418

Income Tax 418

Unequal Proposal Lives 418

Lease Versus Capital Investment 420

Uncertainty 420

Changes in Price Levels 420

Qualitative Considerations 421

Capital Rationing 421

CHAPTER

11

Cost Allocation and Activity-Based

Costing 443

Product Costing Allocation Methods 444

Single Plantwide Factory Overhead Rate Method 445

Multiple Production Department Factory Overhead Rate

Method 447

Department Overhead Rates and Allocation 448

Distortion of Product Costs 449

Activity-Based Costing Method 451

Activity Rates and Allocation 453

Distortion in Product Costs 454

Dangers of Product Cost Distortion 455

Activity-Based Costing for Selling and Administrative

Expenses 456

Activity-Based Costing in Service Businesses 458

Business Connection: Finding the Right Niche 461

CHAPTER

12

Cost Management for Just-in-Time

Environments 489

Just-in-Time Practices 490

Reducing Inventory 490

Reducing Lead Times 491

Reducing Setup Time 492

Business Connection: P&G’s “Pit Stops” 495

Emphasizing Product-Oriented Layout 495

Emphasizing Employee Involvement 496

Emphasizing Pull Manufacturing 496

Emphasizing Zero Defects 496

Emphasizing Supply Chain Management 497

Just-in-Time for Nonmanufacturing Processes 497

Accounting for Just-in-Time Manufacturing 499

Fewer Transactions 500

Combined Accounts 500

Nonfinancial Performance Measures 502

Direct Tracing of Overhead 502

Activity Analysis 503

Costs of Quality 503

Quality Activity Analysis 504

Value-Added Activity Analysis 506

Process Activity Analysis 507

CHAPTER

13

Statement of Cash Flows 529

Reporting Cash Flows 530

Cash Flows from Operating Activities 531

Cash Flows from Investing Activities 533

Cash Flows from Financing Activities 533

Noncash Investing and Financing Activities 533

Business Connection: Too Much Cash! 533

No Cash Flow per Share 534

Statement of Cash Flows—The Indirect Method 534

Retained Earnings 536

Adjustments to Net Income 536

Dividends 541

Common Stock 541

Bonds Payable 542

Building 542

Land 543

Preparing the Statement of Cash Flows 543

Statement of Cash Flows—The Direct Method 544

Cash Received from Customers 545

Cash Payments for Merchandise 546

Cash Payments for Operating Expenses 547

Gain on Sale of Land 547

Interest Expense 547

Cash Payments for Income Taxes 548

Reporting Cash Flows from Operating Activities—Direct

Method 548

Financial Analysis and Interpretation 549

Appendix: Spreadsheet (Work Sheet) for Statement of Cash

Flows—The Indirect Method 550

xxix

Analyzing Accounts 550

Retained Earnings 550

Other Accounts 552

Preparing the Statement of Cash Flows 552

Price-Earnings Ratio 603

Dividends Per Share 604

Dividend Yield 604

Summary of Analytical Measures 604

Corporate Annual Reports 606

CHAPTER

14

Financial Statement Analysis 583

Basic Analytical Methods 584

Horizontal Analysis 585

Vertical Analysis 587

Common-Sized Statements 588

Other Analytical Measures 590

Solvency Analysis 590

Current Position Analysis 591

Accounts Receivable Analysis 593

Inventory Analysis 594

Ratio of Fixed Assets to Long-Term Liabilities 596

Ratio of Liabilities to Stockholders’ Equity 596

Number of Times Interest Charges Earned 597

Profitability Analysis 598

Ratio of Net Sales to Assets 598

Rate Earned on Total Assets 599

Rate Earned on Stockholders’ Equity 600

Rate Earned on Common Stockholders’ Equity 601

Earned Per Share on Common Stock 602

xxx

Management Discussion and Analysis 606

Report on Internal Control 606

Report on Fairness of Financial Statements 607