Upstream Planning: Tax Strategy for Appreciated Assets

advertisement

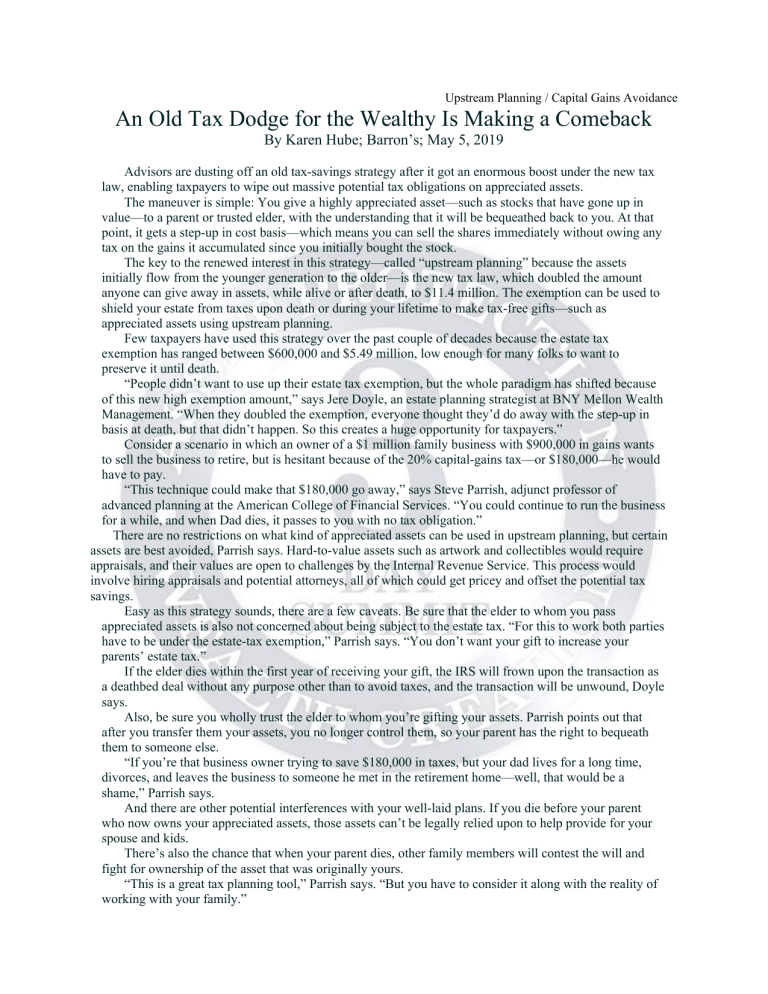

Upstream Planning / Capital Gains Avoidance An Old Tax Dodge for the Wealthy Is Making a Comeback By Karen Hube; Barron’s; May 5, 2019 Advisors are dusting off an old tax-savings strategy after it got an enormous boost under the new tax law, enabling taxpayers to wipe out massive potential tax obligations on appreciated assets. The maneuver is simple: You give a highly appreciated asset—such as stocks that have gone up in value—to a parent or trusted elder, with the understanding that it will be bequeathed back to you. At that point, it gets a step-up in cost basis—which means you can sell the shares immediately without owing any tax on the gains it accumulated since you initially bought the stock. The key to the renewed interest in this strategy—called “upstream planning” because the assets initially flow from the younger generation to the older—is the new tax law, which doubled the amount anyone can give away in assets, while alive or after death, to $11.4 million. The exemption can be used to shield your estate from taxes upon death or during your lifetime to make tax-free gifts—such as appreciated assets using upstream planning. Few taxpayers have used this strategy over the past couple of decades because the estate tax exemption has ranged between $600,000 and $5.49 million, low enough for many folks to want to preserve it until death. “People didn’t want to use up their estate tax exemption, but the whole paradigm has shifted because of this new high exemption amount,” says Jere Doyle, an estate planning strategist at BNY Mellon Wealth Management. “When they doubled the exemption, everyone thought they’d do away with the step-up in basis at death, but that didn’t happen. So this creates a huge opportunity for taxpayers.” Consider a scenario in which an owner of a $1 million family business with $900,000 in gains wants to sell the business to retire, but is hesitant because of the 20% capital-gains tax—or $180,000—he would have to pay. “This technique could make that $180,000 go away,” says Steve Parrish, adjunct professor of advanced planning at the American College of Financial Services. “You could continue to run the business for a while, and when Dad dies, it passes to you with no tax obligation.” There are no restrictions on what kind of appreciated assets can be used in upstream planning, but certain assets are best avoided, Parrish says. Hard-to-value assets such as artwork and collectibles would require appraisals, and their values are open to challenges by the Internal Revenue Service. This process would involve hiring appraisals and potential attorneys, all of which could get pricey and offset the potential tax savings. Easy as this strategy sounds, there are a few caveats. Be sure that the elder to whom you pass appreciated assets is also not concerned about being subject to the estate tax. “For this to work both parties have to be under the estate-tax exemption,” Parrish says. “You don’t want your gift to increase your parents’ estate tax.” If the elder dies within the first year of receiving your gift, the IRS will frown upon the transaction as a deathbed deal without any purpose other than to avoid taxes, and the transaction will be unwound, Doyle says. Also, be sure you wholly trust the elder to whom you’re gifting your assets. Parrish points out that after you transfer them your assets, you no longer control them, so your parent has the right to bequeath them to someone else. “If you’re that business owner trying to save $180,000 in taxes, but your dad lives for a long time, divorces, and leaves the business to someone he met in the retirement home—well, that would be a shame,” Parrish says. And there are other potential interferences with your well-laid plans. If you die before your parent who now owns your appreciated assets, those assets can’t be legally relied upon to help provide for your spouse and kids. There’s also the chance that when your parent dies, other family members will contest the will and fight for ownership of the asset that was originally yours. “This is a great tax planning tool,” Parrish says. “But you have to consider it along with the reality of working with your family.”

![----Original Message----- From: [ ] Sent: Monday, March 14, 2005 1:52 PM](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015588457_1-c7ec3906ed94c9019b2101e3ce2ab4ac-300x300.png)