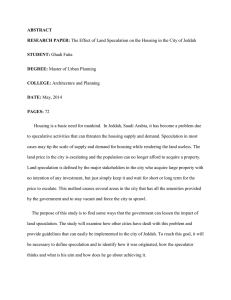

The click of a button Video games and the mechanics of speculation Cameron Kunzelman This article argues that video games have a unique mode of generating speculation within the context of sf. While the formal speculative qualities of written material and films are well known and understood, the techniques of speculation that are unique to games are undertheorised. By looking to two short games whose primary mode of interaction is the click, this article elucidates the moment when video games generate speculation. Speculation is defined here both in the context of sf as a genre and speculation itself as a philosophical act that contemplates being beyond the accepted bounds of reality and empiricism. In conversation with the philosophical work of Quentin Meillassoux, this article concludes that games can offer a speculative mode of thinking that goes beyond empirical projection, and that the speculation provided by a video game can escape contemporary modes of thought and generate new ones. Keywords: video games, speculation, Meillassoux, sf, philosophy Introduction The question of how games perform speculation is an open one. As Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr, writes in the introduction to his The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction, a vast amount of science fictional and speculative work happens at the nexus of written and visual media. The methods best used for discussing that visual media, however, are not necessarily the same ones that provide the best approach to written texts, and he suggests that sf studies more broadly must fully appreciate ‘the technical ways with which film conveys its meanings, and the cognitive and aesthetic engagements that inexorably attend cinematic appreciation’ (11) so that scholars can better ground their analysis of sf within that medium. He also includes video games, stating that ‘although [the] medium is only emerging, and there has been as yet little reflection on the aesthetic and cognitive aspects of constructing sf in it, it is abundantly clear that the genre is a privileged source of its narratives and effects’ (11). It is my argument that the video game, being a developed medium for 40 years, is not merely emerging, it has fully emerged, and in doing so it has generated its own methods of engaging with the genre trappings and conceptual schema of sf. In this essay, I will look to two games: Queers in Love Science Fiction Film and Television 11.3 (2018), 469–90 © Liverpool University Press ISSN 1754-3770 (print) 1754-3789 (online) https://doi.org/10.3828/sfftv.2018.27 470 Cameron Kunzelman at the End of the World (Anthropy 2013) and Impetus (Johan, Oelze and Lonien 2013). It is my claim that these games do exactly what Csicsery-Ronay is seeking in the realm of sf studies’ relation to games; these games have their own ways of approaching and furthering the modes of thinking at the root of sf. It is also my claim that these two games illustrate how video games encourage speculation in the player through their specific modes of interaction. Instead of merely using the genre identifiers of sf as a way of creating a generic heroism-in-space plotline, these two small experimental games demonstrate how the mechanic of the click can function as an act of speculation which moves beyond the traditional literary or cinematic modes of speculation that readers generally expect from sf more broadly. What is the importance of the click? It is one of the most minimal interactions that a player can have with a game. It is singular, but it can be repeated, and it can perform myriad actions. You can click to achieve anything, from organising a whole world in Civilization VI (Beach et al. 2017) to placing two blocks of dirt on top of each other in Minecraft (Persson 2011). While the click is most often used in combination with other actions, like mouse movements or keyboard key commands, focusing on the minimal interaction of the click itself is a starting place for understanding how games proliferate speculation. The keyboard–mouse movement–click assemblage is similar to the sentence in written work or the scene in cinema; the click is the video game version of the word or the shot. It is the minimal portion, and yet it provides the platform for vastly different modes of interaction. By beginning at this smallest form, we can understand what the click does, which then allows us to better understand what it can do in combination with other forms of interaction. It is my contention that the click gives us a focal point for understanding how speculation functions in relation to the video game. To argue this point, some steps must first be taken to set bounds on both speculation and the objects that best exemplify how the click functions. First, I will briefly introduce both games in order to explain how each depend on the mechanical action of the click. Second, I will look at speculative philosophy and sf’s understanding of speculation in order to inform a dual reading of speculation both as empirical assumptions about the future and as contemplation being outside of human knowledge. Lastly, I will look to how both Queers in Love at the End of the World and Impetus each uniquely inform these modes of speculation by deploying a click as speculation. Before delving headfirst into the concept of speculation, it is important to note the difference between games that deploy sf as a series of genre identifiers and games that deploy sf for its ability to generate speculation. To do this, it is The click of a button 471 appropriate to consider briefly the tight-knit history of video games and sf. In 1961, MIT received a PDP-1 computer from the Digital Equipment Corporation. The Tech Model Railroad Club, a student organisation at the institute, put together a small committee to puzzle out what they could do with the platform. After a short deliberation, members Wayne Witaenem, Martin Graetz and Steve Russell decided that they would attempt to make a video game. The latter was designated as the programmer, and after some delays, he produced a sleek game called Spacewar! In the game, two players battled each other with space ships, and both the design and the look of the game were heavily influenced by the sf of the time period (Donovan 10). In an article on the origins of the game published in 1981, J.M. Graetz states it much more starkly: ‘Most of the blame falls on E.E. Smith’ and his stories in which ‘overdeveloped Hardy Boys go trekking off through the universe to punch out the latest gang of galactic goons, blow up a few planets, kill all sorts of nasty life forms, and just have a heck of a good time’ (Graetz n.p.). Spacewar!’s legacy is one of the most significant in video games. Galaxy Game, released by Bill Pitts in 1971, and Computer Space, released two months later by Ted Dabney and Nolan Bushnell, are widely recognised as two of the first commercial arcade game machines. These two games absorbed and emulated the spaceship action of Spacewar!, and sf concepts and content have been at the core of video games and game culture since. From the perspective of public perception of the game industry, Edge, a popular gaming magazine that has been running since 1993, published a special issue titled ‘The 100 Greatest Videogames’ in 2015. Within those, at least 24 can be considered directly science-fictional (including The Last of Us, Bioshock and Half Life 2) while another dozen are somewhere on the edge of sf and fantasy. Within scholarly work, Tanya Krzywinska and Esther MacCallum-Stewart also demonstrate a similar lineage in their chart of sf digital games in their chapter on the topic in The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction, highlighting more than 24 major games using sf themes or concepts from the release of Spacewar! to Halo 3’s release in 2007 (350–1). It is worth noting that the way in which genre works in games is distinct from other media. Heuristically, we are comfortable with categorising films or novels into mysteries, dramas, horror tales and various other genre identifiers. Within video games, there is an elision between ‘genre’ as we understand it in other media and the specific, interaction-focused genres that appear in video games. In ‘Genre and Game Studies: Toward a Critical Approach to Video Game Genres’, Thomas H. Apperley argues that games should be classified into genres not by their representational characteristics but instead by their 472 Cameron Kunzelman different modes of interactions. To follow Apperley’s argument, the crux of the debate around genre in games has nothing to do with what you are looking at or hearing, and everything to do with how you are interacting with that system – which means that game genres, such as ‘simulation’ and ‘action’, hold precedence over whatever actual content you are seeing. While I have sympathy for this argument, and I do maintain alongside Apperley that the mode of interaction with a game is a primary location of interest, this classification of genre seems strongly decoupled from the actual experience of the field of games. Perusing the popular tags on Steam, the largest platform for computer games, produces a number of results that hold to Apperley’s argument: action, adventure, strategy and simulation are all there. Alongside these, though, are generic identifiers that we would likely see in other media: horror, sf, fantasy, funny. These genres are not hidden away inside some kind of submenu or presented with any additional qualifiers; within the realm of actually played games, genres as modes of interaction and genres as representational qualities are not either/or but both/and. If there is a difference, it is a difference purely in theory and not in practice. To assert that a game with sf representational elements is not a game in an sf genre is the equivalent of saying that Transformers: The Last Knight (Bay US 2017) is an action film, not a sf film. The sf games that I am addressing in this piece are after something other than what the top sellers in the genre are doing, however. Impetus and Queers in Love at the End of the World both eschew the bombast and mechanical complexity of a game like the omnibus action-stealth-zombie hit The Last of Us (Straley and Druckmann 2013). In this game, or in the popular Halo franchise, the spectacle of what sf offers (the end of the world via plague or robot armies from the deep past) is used as a structuring set of tropes within which one can place methods of interaction that are agnostic to that representational content. In many ways, this is similar to the sf pulps, in which stock situations were used as complete blocks of content that could be stacked in novel ways. In Krzywinska and MacCallum-Stewart’s analysis, this form of taking on sf in games ‘privileges spectacle and action over contemplation, and [is a site] in which speculation, clearly integral to the act of playing games, is not as radically realized as is possible’ (353). In the same way that the ‘heck of a good time’ books of E.E. Smith enabled Spacewar!’s particular gameplay elements of two ships firing at each other, the sf elements of The Last of Us or Halo merely provide a shortcut to narratively grounding a particular kind of gameplay. In contrast to the spectacular, action-based games mentioned above, Queers in Love at the End of the World and Impetus are two video games that do not The click of a button 473 simply use sf as a set of generic identifiers to ground first-person shooting or third-person action. In these games, sf is not merely its representational content of rocket ships and laser guns. Rather, they embrace the element of speculation that Krzywinska and MacCallum-Stewart claim is possible within sf video games. If games like The Last of Us are not able to ‘realize’ speculation to its utmost potential, then Impetus and Queers in Love at the End of the World embrace it to the exclusion of all else. Each is propelled by the relationship between the world that the player inhabits while playing and the world that exists over the horizon line of the game’s ending. Both, in short, are fully dependent on the player’s ability to imagine a world that exists after the game is finished, and both attend to that act of speculation through a very particular mechanism: the click. With the distinction between sf-as-genre identifiers and speculation established, I will now look to two modes of understanding speculation so that we may begin to see why Queers in Love at the End of the World and Impetus are unique in how they present speculation to us. Playing the word game Before proceeding with my analysis, it is worth considering if these two experimental games, both certainly at the fringes of games both culturally and mechanically, are actually games at all. Disciplinarily, games studies has had a number of formalised debates about the boundaries of what constitutes a game, digital or otherwise, and while I have little interest in rehearsing those debates here, there are stakes to positioning how these two games use clicks to inform how we understand games in general. Queers in Love at The End of the World is a text-based game in which the world ends. Created with the Twine hypertext game creation tool, the game is played in a browser. When the player initially navigates to the game, they are presented with the word ‘begin’ in blue against a black background. The word is a hyperlink, and after the player clicks the word, the screen changes. A paragraph of text appears, and a circular white timer begins counting down on the left side of the page. The first block of text is descriptive, and it contains several different words as links within it that the player can then click on to progress the story forward: ‘In the end, like you always said, it’s just the two of you together. You have ten seconds, but there’s so much you want to do: kiss her, hold her, take her hand, tell her.’ In the previous sentence, the bolded words are those links, and if the player clicks on ‘kiss’, the game takes them to 474 Cameron Kunzelman Screenshot of Anna Anthropy, ‘Queers in Love at the End of the World’. yet another screen. Upon clicking ‘tell’, for example, the player is then brought to a screen in which a small conversation plays out. Then, at the bottom of that screen, there are four more options that will push the narrative action forward. While the player is clicking these particular narrative threads, the timer on the left of their screen is counting down. It begins at ten seconds, and it counts down in real time. A first-time player might only make it through two screens before the timer hits zero, and when that happens the game immediately cuts to a screen with a simple bit of text: ‘Everything is wiped away.’ The player then has the option of reading an afterword, which is a graphic of the words ‘when we have each other we have everything’, or clicking a restart link, which puts them back at the beginning of the game. The counter ticks down on the left side, and the narrative begins anew. A player clicking at maximum speed cannot exhaust the game’s narrative branches in a single playthrough, and there is a possibility of hitting narrative dead-ends that do not allow for forward progress into additional parts of the narrative. There is no way to see the ‘whole story’, and most players will be limited by the timer more than they are limited by the branches of the game itself. Within Queers in Love at the End of the World, the amount of clicking that a player does has no impact on when the already-written future arrives. The end of the game is coming, and it cannot be deferred, it can only be repeated endlessly in replays of the game. The click of a button 475 Screenshot of Dominik Johan, Jan Oelze and Jeremy Lonien, ‘Impetus’. Impetus, developed over a 48-hour period in August 2013 for the game development event Ludum Dare 27 and no longer operable, was composed of a single screen. A female astronaut is positioned in the middle of the screen. The description page for the game states that ‘Impetus has lost consciousness and her systems will fail in 10 seconds’ (Johan, Oelze and Lonien). Playing the game consisted of loading the live web page and clicking on the astronaut, and the stakes for doing so were high. As the developers explain on the game’s page, ‘Death is inevitable, but it can be delayed. Sustain Impetus’ life by pressing the button, which will reset the timer. Once it runs out, the game is over and can never be played again.’ With these basic descriptive facts, the game was released into the world. The reception of the game was momentous and immediate. While the game was initially played by only the three members of the development team, when the time came for them to sleep, they had to hope that the Ludum Dare community of game creators and fans of the game on Twitter would sustain it through to the next day. In his essay reflecting on the game, designer Dominik Johan confesses that upon waking the next morning he assumed that someone had written a script to keep the game alive. More than 25,000 timer resets, or individual human clicks, had generated more than 30,000 additional seconds of Impetus’s life (Johan). The second day of Impetus’s life, Johan was interviewed by the newspaper Spiegel Online. The publication of the 476 Cameron Kunzelman interview generated a huge influx of web traffic for the server on which Impetus was hosted. According to a graph shared by Johan, there were roughly 16,000 players of the game before the web hosting company shut it down due to the sheer amount of stress it had been putting on the hosting server. On 27 August 2013, Impetus was shut down for good. In the estimation of a scholar like Jesper Juul, neither of these games are games in a classic sense; if we were to plot them on his well-cited diagram of games, borderline cases and not-games, they could only charitably be put into the borderline category (Juul 44). Queers in Love at the End of the World is built with the hypertext tool Twine, and Juul places hypertext fiction squarely outside of the category of ‘game’ due to its fixed outcome. Similarly, Impetus might best be understood as analogous to open-ended simulations, which Juul argues are borderline cases due to their lack of valorised outcomes. You could not win Impetus; you could simply forestall its ending. To make these classifications, however, is to miss that Queers in Love at the End of the World has a clear fail state in the timer running down and is no more deterministic than any other narrative game that begins at an arbitrary plot point and ends at another. Similarly, Impetus clearly had fixed rules (in the clicking mechanic), negotiable consequences (you can care about the outcome of the game however you wish), player attachment to outcome (the massive outpouring of affect-asclick) and player effort (the clicking itself). The lack of the last two qualities, valorisation of outcome and variable outcome, could just as easily be applied to any number of puzzle or hidden object games. To evoke Juul’s definition of games as the sole definition is to make claims of formal specificity at the cost of a wide swathe of experiences that are understood to be games by millions of people the world over – and if our formal definitions of games are not capturing things that are generally understood to be games, then it is unclear what the value of these definitions is. If we turn to the work of Janet Murray, and her definition of games as ‘joint attentional scenes’, we can perhaps get a better handle on how these games are functioning (Murray 187). Within this definition, what games are is less important than what they do as organisational forces and directors of focus. Within Murray’s paradigm, a game is merely a set of patterns that communicates and codifies specific behaviours. For her purposes, it is better to be agnostic about the specificities of what a game is, since it is only through casting a wide net that we can understand how games and adjacent activities impact culture, communicate knowledge and declare cultural expectations. Murray is not the only person who rejects a strong, categorical definition of a game in favour of a more open one. Jon Sharp gives us ‘a goal for the player The click of a button 477 to achieve, actions with which the player can achieve the goal, and resistance thwarting the player’s progress toward the goal’ as the ‘core components’ of a game (Sharp 8). Brian Schrank, writing specifically on experimental games, suggests that game designer Will Wright’s claim that his SimCity and The Sims are ‘software toys rather than games’ in the face of mainstream culture’s clear understanding of them as games is one of many reasons that we should ‘allow many definitions of videogame to aggregate into a composite, fractured image’ that is ‘lively, challenging, and historically grounded’ (Schrank 12). Indeed, Anna Anthropy and Naomi Clark write in their co-authored book on game design that ‘games are made of rules’, full stop (Anthropy and Clark 14). Within this wider framework, and certainly the frameworks of the designers, both Impetus and Queers in Love at the End of the World are video games, even if they are on the fringes of the medium. Indeed, it is their quality of being on the fringe that gives them their explanatory and exploratory potential. Freed from the expectations of mechanical complexity and interlocking control systems of traditional games, the intense focus on the singular mode of interaction in these games – the click – enables us to understand how the click itself works. There are two prominent characteristics shared between these games. The first is the click, which drives all of the player’s interaction with the games. In Queers in Love at the End of the World, the player is clicking the narrative elements until the ability to click is removed by the countdown timer. In Impetus, the player clicks the figure in the middle of the screen in order to keep the game playable and existent. I will return to these clicks and what they do in the third section of this essay. The second characteristic that the two games share is their relationship to sf. Queers in Love at the End of the World’s timer is diegetically realised as some kind of apocalyptic event (the ‘end of the world’ of the title), an oftendeployed standby of sf that stretches back to its origins. All of the player’s interactions in the game are measured against the reality that any given play session will be erased, and that the only thing that can be taken from those play sessions is what the player can retain of the experience. For Impetus, the genre concepts of sf are contained in the visual elements of the game. While I have characterised the figure on the screen as an astronaut, that description is not necessarily supported by either the game or the designers. Rather, Impetus is simply a person who is attached to a number of different tubes, and those tubes keep her alive. This system could be a mech suit, a spaceship cryostasis unit or any other sf device that can keep a human alive. Like Queers in Love at the End of the World, Impetus holds definitive information at a 478 Cameron Kunzelman distance from the player, giving them only what they need to know to keep interacting with the game. With the objects clearly described and their positions in both genre and video games established, I will now move to an elaboration of how speculation functions in relation to the unknown future that both of these games gesture towards. The wiping away of Queers in Love at the End of the World and the continual hope of keeping Impetus living forever in Impetus both rely on the conceptual structure of speculation. In the next section, I will elaborate the philosophical perspective that gives us some purchase on how games function in regard to speculation. Speculations on speculation There are two strong senses of speculation at work in the two games I have endeavoured to explore here. The first is the speculation of speculative fiction. The second is the speculation of speculative philosophy. In this section, I will briefly explore the former before turning to the latter in order to elaborate a theory of the relationship between speculation itself and the mechanics of speculating. In a longform 1997 essay commenting on Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, Samuel R. Delany offers some remarks on how speculation functions in sf more generally. He offers a ‘pair of parameters’ as a sort of engine for how sf operates: ideohistory and conventions of omission (Delany 273). The first is a sense of history of the ideas and structuring ideologies of a given fictional world, and the second is the mode of writing that strategically omits that sense of history to give it a sense of fullness of which the reader is only receiving pieces. What this dialectical pair gives to the writer and the reader is a sense of how the new is produced within any given sf work; by having a sense of a filled-in history of ideas, we can understand how a given event in the sf work has significance in relation to the fullness of ideohistory. Delany claims that this pair of concepts ‘create a richly contoured field capable of infinite modulation, in which exploration can proceed in any direction, and within which any number of subtle points can be posited’ (273) by the sf writer. It is from this argument that Delany posits a short theory of the speculation of speculative fiction. He writes that the dyad of ideohistory and the writing of omission ‘are what finally allow science fiction to treat ideas as signifiers – as complex structures that organise outward in time and space (they have causes, they have results) as well as inward (their expressions, their forms, The click of a button 479 their deconstructions)’ (273). These modes of writing sf ‘are what free science fiction from the stricture that has held back so much modern thought, of treating ideas as signifieds – as dense, semantic objects with essential, hidden, yet finally extractable semantic cores’ (273). For Delany, this recognition of the ‘complex signifiers’ liberates sf from eternal truths or essences, and opens up the field of potential within the field. He finishes this argument with a specific claim about speculation: We must remember that in science fiction, speculation is a metaphor for knowledge; too many critics today find themselves arguing, however inadvertently, that (rather than ceding to this metaphoric hierarchy) knowledge of some sort of prior, privileged system (say, ‘science’) can or must generate some metaphoric commentary on the use, workings, and efficacy of speculation itself. This is simply not the case. (273–4) Within this reading of The Dispossessed, Delany is putting forward a set of mechanics through which speculation itself can be seen to emerge within writing. First, there is a conceptual history of a world, and there is the slow leaking or revelation of that conceptual history to the reader of a given text. The last quotation, however, makes it clear that the work of speculation is not merely that of proving a previously existing system that exists outside the ideohistory of the world presented in a given sf work. On the contrary, speculation is the act of building from those presuppositions, and demonstrating the newness or ruptures that happen within those spaces when the fictional world encounters something that has not existed within it previously.1 Delany claims that the error in The Dispossessed is not in the creation of the world, but that the basics of its ideohistory are not sufficiently developed enough for the reader to understand where the speculation, or the generation of new knowledge in the context of that world, is occurring. Instead, the reader is left depending on their own assumptions about the structure of the world of the novel, and it is therefore difficult to see where speculation happens. Similarly, in The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction, Csicsery-Ronay remarks on the notorious difficulty of defining sf, and suggests instead that we look to a concept of ‘science fictionality’ instead (3). Science fictionality is not a genre marker or a cluster of signifiers, but instead a kind of process. It is a ‘mood or attitude, a way of entertaining incongruous experiences, in which judgment is suspended, as if we were witnessing the transformations happening to, and occurring in, us’ (3). This attitude of science fictionality, like Delany’s arguments about sf, is animated by ‘gaps’ or drives, and one is historical-logical and ‘lies 1. This empirical building process is similar to the novum as the concept is developed by Darko Suvin in his Metamorphoses of Science Fiction (1979). 480 Cameron Kunzelman between the conceivability of future transformations and the possibility of their actualization’ (3). For Csicsery-Ronay, this drive is completely controlled by the empirical conclusions that one can draw from a set of conditions. R.B. Gill’s discussion of the genre of speculative fiction also orbits similar concerns about the work of speculation to those that Delany puts forward. Working towards an inclusive definition that includes all common and popular conceptions of the genre, Gill claims that speculative fiction is ‘speculative representation of what would happen had the actual chain of causes or the matrix of reality-conditions been replaced with other conditions’ (Gill 73). For Delany, speculation is enabled by the conditions of the ideogram and then a focus on extrapolation from there; for Gill, that extrapolation is given meaning in contrast to the conditions of the world in which the reader lives. That baseline mode of speculation is also at work in speculative philosophy. In their introduction to The Speculative Turn, an edited volume that put many strands of contemporary philosophy in conversation with each other, editors Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek and Graham Harman summarise the labour of speculation in speculative philosophy: speculation ‘aims at something ‘beyond’ the critical and linguistic turns. As such, it recuperates the pre-critical sense of ‘speculation’ as a concern with the Absolute, while also taking into account the undeniable progress that is due to the labour of critique’ (3). While the essay you are reading is not a full-throated defence of speculative philosophical endeavours, it is precisely the quality of speculation that reaches beyond the readily acquired representations that seems to draw interest from both Delany and Gill in the essays mentioned above. Indeed, for Alfred North Whitehead, a prominent figure in several strands of speculative philosophy, the act of speculation is an ‘imaginative construction’ that required an ‘unflinching pursuit’ of ‘coherence and logical perfection’ (8). ‘Speculative boldness’, he writes, ‘must be balanced by complete humility before logic, and before fact’ (8). What unites the two speculations (fiction and philosophy) is a fidelity to consistency based on specific principles that are stated up-front as nearly axiomatic. Additionally, it is a fidelity to those principles that extend beyond the knowable or the provable.2 A given fictional world does not have a prewritten future, but we can speculate about what that might be based on from the information we are given about that world’s people, chemical makeup, solar system and other given information. Similarly, we are left to speculate about the existence of the universe in which we live. Given what we know, and armed 2. Quentin Meillassoux calls this ‘dogmatism’, but he does not use this term in the strictly negative sense that we might normally associate it with. The click of a button 481 with Whitehead’s fidelity to logical consistency, we can extrapolate out into encompassing statements about how these games and our reality might function. Quentin Meillassoux’s work on contingency, however, puts pressure on some of the claims about speculation that I have outlined here. If speculation is about logically following through on given principles, then it is largely an act of fictional empiricism; what is given in one instance is extrapolated into another, and then the next, and so on. Meillassoux’s After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency is a short book that defends speculation but problematises how we have tended to understand it in the past. It is impossible to properly summarise After Finitude; it is a dense text that coils around itself, with Meillassoux slowly working his way through the assumptions of the history of philosophy in order for the reader to understand the significant, yet finely-grained, claims that he is making. The goal of After Finitude is to reassert the human ability to think about what he variously calls ‘the absolute’ and ‘the great outdoors’ (Meillassoux 7). This is a significant manoeuvre in that Meillassoux is fundamentally rejecting most philosophy since Immanuel Kant, whose philosophy of the transcendental subject set the groundwork for philosophers who assumed that we could never properly consider things-in-themselves. Put in other terms, for Kant, we can only properly think about and consider objects in the world that we have human access to, and we can never truly access other things; we merely have our perceptions of them. Meillassoux, in contrast, defends the human ability to consider the existence of things both before and after the existence of humans, or the individual human. While the specifics and stakes of the book proper are not important for our discussion here, two of Meillassoux’s supporting arguments are crucial for thinking about how the games we are discussing provide for a mechanic of speculation. The first argument critical for us in After Finitude is Meillassoux’s elaboration of what he calls facticity. In the philosophical argument being put forward, there are two forms of relationship to possibility. Contingency, Meillassoux argues, ‘expresses the fact that physical laws remain indifferent as to whether an event occurs or not – they allow an entity to emerge, subsist, or perish’ (39). Contingency is at work, for example, when we are watching a juggler plying her trade on a crowded street corner. The balls might fall; someone might run into her; she might trip; she might start laughing; the sidewalk might crack from the heat; and so on. In contrast to this, facticity ‘pertains to those structural invariants that supposedly govern the world’ and ‘provide the minimal organization of representation: [the] principle of causality, forms of perception, logical laws, etc.’ (39). Where contingency grants the consistency 482 Cameron Kunzelman of basic laws of the universe, facticity radicalises those ideas by suggesting a contingency of contingency itself. The concept of facticity when applied to the juggler assumes that she could turn into a 2D object, that all oxygen could disappear from the universe, that gravity could fluctuate without reference or recourse to the moments before it. It is important to note here that Meillassoux isn’t saying that this could one day happen; rather, he is claiming that this is the current structure of reality. We currently live within a world of facticity, of the contingency of contingency, and that we should recognise that any spilling over into ‘hyper-Chaos’ (64) would not be an interruption of the normalcy of things from a philosophical standpoint. Meillassoux’s characterisation of reality as one where facticity should be taken seriously is related to his evocation and proposed solution to Hume’s Problem, a philosophical conundrum first put forward in the work of David Hume and then proposed formally by Kant. While Hume’s Problem has been a concern of many philosophers in the ensuing centuries, including Karl Popper during the twentieth century, it is the principle of facticity as Meillassoux understands it that provides an intriguing inroad to thinking about how the Problem functions. What is Hume’s Problem, then? Meillassoux proposes it in this way: ‘Is it possible to demonstrate that the same effects will always follow from the same causes ceteris paribus, i.e. all other things being equal? In other words, can one establish that in identical circumstances, future successions of phenomena will always be identical to previous successions?’ Summarised further, Meillassoux puts the Problem this way: ‘Can we demonstrate that the experimental science which is possible today will still be possible tomorrow?’ Quentin Meillassoux evokes Hume’s example of the billiard balls in An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding in order to elucidate what he means. Hume, outlining his philosophy of both causality and empiricism, writes: ‘When I see, for instance, a billiard-ball moving in a straight line towards another; even suppose motion in the second ball should by accident be suggested to me, as the result of their contact or impulse; may I not conceive, that a hundred different events might follow from that cause?’ He ends the example with a taut conclusion: ‘When then should we give preference to one, which is no more consistent or conceivable than the rest? All our reasonings a priori will never be able to show us any foundation for this preference’ (Hume 111). For Hume, it is ultimately the predictive capacity of empiricism that allows us to make ­substantiated guesses about how the billiard balls will ultimately move. The crucial move that Meillassoux makes with the principle of facticity and his presentation of Hume’s Problem is that he posits a speculative answer to it. Contingency suggests that we have a sense of where the billiard balls will The click of a button 483 move, if not absolute knowledge. Facticity means that we do not even know if the physical laws of reality will allow for that movement to occur. Facticity radicalises Hume’s Problem to the extent that we cannot predict whether the natural forces which subtend the Problem itself can hold. This reality, the true operationalising of facticity, is the ultimate payoff for embracing Meillassoux’s version of speculation. It is only through speculation, or through attempting to think the absolute Outside of all the things that humans take for granted in their world, that we can access and take seriously facticity itself. ‘Speculation’, Meillassoux writes, ‘proceeds by accentuating thought’s relinquishment of the principle of reason to the point where this relinquishment is converted into a principle, which alone allows us to grasp the fact that there is absolutely no ultimate Reason, whether thinkable or unthinkable’ (Meillassoux 63). It is here that we can see the key difference between the speculations of speculative fiction as typified by Delany and speculative philosophy as presented by Meillassoux: the former relies on the development of empirical concepts and ideas to project a future forward in time, and the latter has foregone that possibility completely both in fiction and in the lived world of you and I. Speculative fiction’s success depends on the qualities of reason. Speculative philosophy’s success depends on the successful unseating of human reasoning as bearing a meaningful interpretation of reality. This distinction reveals the dual nature of speculation, and how it can be both bound and unbound in productive ways. Speculation can be the thought about logical conclusions, but it can also produce ways of contemplating the structure of reality that has no recourse to already-known ways of thinking and being in the world. The gap between those two modes of speculation is especially important when it comes to speculating not just about reality, but about the future that stretches out from any given moment. In another short book, Science Fiction and Extro-Science Fiction, Meillassoux categorises the kind of speculation that Delany advocates for as the domain of sf proper. Here, sf ‘is a matter of imagining a fictional future of science that modifies, and often expands, its possibilities of knowledge and mastery of the real’ (Meillassoux ‘Extro’ 3–4). He claims that this mode always follows the axiom that ‘in the anticipated future it will still be possible to subject the world to scientific knowledge’ (5). By contrast, he claims that what he calls ‘extro-science fiction’ is the creation of worlds that are ‘inaccessible to human knowledge, so that they cannot be established as the object of natural science’ (6). Without delving into the argument deeply, as it ultimately has little to do with what I am discussing here, the fundamental divide that he sees here is the one between speculation as empiricism and speculation as 484 Cameron Kunzelman contemplating the world outside of the human potential for understanding and knowledge-generation. Meillassoux’s ‘discovery’ of his arguments about speculative philosophy are important because he sees them as latent within already-accepted modes of thinking about the world. The principle of facticity and his acceptance of Hume’s Problem are not made whole-cloth out of nonexistent argument. Rather, he reaches his conclusions about both by taking the accepted philosophical principles of contingency, causality and empiricism to find these radical arguments already existing within them, and yet not taken to their furthest extremes. In the next, and final, section of this essay, I will look to the two games introduced earlier to elucidate how the two modes of speculation both exist within them and are brought to bear by the mechanic of the click. How do games speculate? The fundamental question about the two forms of speculation and their relationship to games is this: How do games speculate? Moreover, how do the two games on display here, Queers in Love at the End of the World and Impetus, operate within the two modes of speculation that I have presented from the critical work of Samuel Delany and Quentin Meillassoux? It is my argument that these two games play at the edge of human experience of causality and empiricism. They both generate speculation itself, and they do it through the mode of interaction that the player has with the game. Clicking with a mouse is an act of speculating, though whether it is of the Delany sort or the Meillassoux sort has yet to be determined. As I explained in the opening of this essay, the click is a kind of minimum viable interaction for video games. It is the equivalent of a quick button press, a single key command or a swipe on a touch device. By focusing in on what clicks do, we can, at least in some ways, put some limits on the analysis of the large assemblage that is formed by a human player, their game hardware and the game software that they are playing. To focus on the click alone is to become a kind of diagnostician in the same way that you would repair a faulty computer part; determining what the click does is much like trying to ascertain if you have a bad stick of RAM. You need to focus in on it, to the exclusion of the other parts, to see how it is working. One might object that this is limiting to some degree, or that it misses the broader concert of social and mechanical interplay that is happening in games, but rest assured that this is a methodical decision The click of a button 485 in the same way that interrogating word choice in poetry analysis or focusing on the shape of particular brush strokes operates in art criticism. The click is so minimal, so fundamentally small, that it fuelled an entire cadre of ‘clicker’ games that thrived on using that minimal reaction to fuel a boom economy in distributing, controlling and monetising the click itself (Lewis, Wardrip-Fruin and Whitehead 179). The click is the atom of the video game, and analysing it tells us a significant amount about the objects and contexts it affords. The speculation of the click is what unites the two games at hand. After all, other than the mode of interaction and their relationship to sf, these games have nothing in common. One is a narrative form that is always cut short, and the other is a completely open-ended clicker that is more similar to an experiment than it is to what most people would imagine are the formal qualities of a game. It is the way that they use the click that makes these games resonate together as objects that help demonstrate the relationship between clicking and speculation. In Queers in Love at the End of the World, the click is a mode of moving through prewritten story segments. Clicking on a piece of text always produces the same event, no matter how many times the player interacts with the game. The text always moves linearly from node to node, and there is no in-game way of altering that meta-structure. A player can choose to interact differently, in the sense that they are interacting with new parts of the game each time, but the fundamental structure of nodes and the links between those nodes will always be the same. Additionally, the timer that counts down in any given play session always counts down in the same way, neither speeding nor slowing in its methodical quest to run down to zero. Playing Queers in Love at the End of the World is an effort of filling out the world of the player. The act of clicking is like that of science. Under controlled conditions that are predictable and known, the player augments and expands their knowledge of a given narrative. Claudia Lo explains this as a fundamental paradox; this is both a game that asks the player to race against the clock and also to accept failure. Lo characterises this as respite, and points our attention to ‘a cathartic satisfaction in deliberately failing in order to reset and try again after learning the exact details of failure’ (Lo 186). Following from this, we can understand this catharsis as the comfort of knowing, finally, how things end. It is the comfort of knowing what happened. When the counter runs down, we can play the game again, and like the scientist in the lab who is repeating an experiment, we can either choose new lines of inquiry or run down the same narrative pathways to confirm what we know. Queers in Love at the End of the World is speculative in that it takes an sf concept (the catastrophic destruction 486 Cameron Kunzelman of things) and then plays out all the possibilities in the time directly before that event. It is wholly deterministic, and in being so, it is as empirically verifiable as the average construction of a water molecule. And, just like that structure of water, what has been experienced (the wetness, the hydration, the interaction with lye) can be compiled together into general knowledge about what happened and what will happen. It is, in essence, the video game equivalent of Hume’s billiard balls: it has many pathways, but those pathways are clearly defined and empirically modellable; the billiard balls might move around, but the table is always flat and dependable. The act of playing Impetus, by contrast, does not provide the same empirical substrate. While the playing of the game can only happen in retrospect due to its nature as an unrepeatable instantiation of the game, the potential set of possibilities on the ‘other side’ of the act of clicking to keep the game’s character alive is much larger. There is no possibility for doing what Meillassoux calls ‘science’, or empirical knowledge, in regard to Impetus because the future is so radically unknown. When a player clicks on the character to keep her alive, it is impossible to know if the game will continue to respect that action. Importantly, the laws of reality do not change in the way that Meillassoux might require; the billiard table does not warp, stretch or skew. However, the server issues that the game experienced due to traffic load disrupted and even fragmented the game into different experiences depending on a player’s connection to the server, all of which were ‘true’ for those players. Some players saw the game over screen, some had counters that passed through zero and kept going, and others were kicked off the web page without any explanation. Paradoxically, the game was both alive and dead, playable and completed, at the same time for different players. For the individual player, this is the hyper-chaos that Meillassoux points to as the logical outcome of facticity. A player of Impetus was not able to reliably imagine what the future of that game was because the rules of interaction changed so radically during the time that it was available to play. What matters here is not just those interruptions, but that the structure of Impetus makes it impossible to know if the game is moving forward ‘correctly’. From the player’s perspective, there is no way of knowing if the paradoxical game state is designed or accidentally deployed. One cannot build empirical knowledge with Impetus during the act of playing; one can only say what has happened, not what will happen during play. In this way, the clicking of Impetus activates the second sense of speculation, the approach to the outside that has no regard for the human ability to render appropriate knowledge of the object at hand. Related to the case of Impetus is The Button, a game created by a moderator The click of a button 487 Screenshot of http://www.reddit.com/r/thebutton (archived). of the internet forum Reddit. Similarly, The Button was a timer-centred game where players could log in to their Reddit account and click a light blue button, which reset a 60-second timer. Crucially, and in a different way from Impetus, each Reddit user could only click the button once, which meant that group organisations immediately formed in order to maximise the number of clicks for the button. Groups dedicated to speculating about the future of the button also emerged from the community, all with specific beliefs about what would happen after the button was no longer pressed or when a certain number of button presses were reached (the button was ultimately clicked 1,008,316 times; when the timer finally expired, nothing happened beyond the Reddit being auto-archived). What unites Impetus and The Button is the speculation that the click itself affords. In these two games, the click forestalls a coming event. Players are left to speculate about what that coming event is. Will the game simply end, leaving players wondering what the experience was about? Will it fundamentally change after it exists for days, months or years? Is there a click threshold for some kind of shift in gameplay? For both of these games, these were all answered in the negative, but that conclusion could not be known by players at the time. By clicking, players deferred the end of the game and at the same time they deferred the revelations that would end speculations. They clicked, and in doing so they both propelled the game into the future and prevented themselves from accessing the very answers to the questions that they were asking. Speculation proliferated while the end of the game was unknown, and the end of the game would always be unknown while players were clicking. In clicking, players enabled their own ability to speculate about what would happen when they stopped clicking. 488 Cameron Kunzelman The two valences of the click in these games, then, are about two modes of speculating. The first, best represented in Queers in Love at the End of the World, is about developing a more robust understanding of a game world. It is using the click as an experimental procedure that triggers speculation, and then deploying empirical fact finding to do the work of extrapolating from the ideograms with which Delany was so concerned with. The second, best represented in Impetus, is the projection of pure speculation outside of expected empirical relations, of contemplating the absolute in which their preconceived notions of games and interactive experience might have no ground or purchase. At the end of things, of course, that speculation can be proved or disproved, but it is precisely in the gap produced between the beginning and the ending that speculation spins up and proliferates. As I have argued here, the click is a minimal interaction that allows us to both pursue the future and defer it. These modes, in turn, allow us to think through two modes of speculation within the sf genre as it appears in games. I have purposefully chosen these small games and their very tight mechanics and rulesets in order to demonstrate a general rule for how interaction generates speculative thoughts in players, and my intention is to provide readers with a tool that can be applied to other video game objects. It is an open question how the additional mechanics and interactions in a time-looping game like The Sexy Brutale (2017) can be understood in conversation with the ideogrammatic form of speculation on which Queers in Love at the End of the World depends. Similarly, the Meillassouxian speculation at work in the eternal present of Impetus must have some presence within the open experiences of a game like EVE Online. There might even be additional modes of speculation that exist beyond the two I have elaborated on here, further highlighting how the games we make ground, instantiate and trouble the relationship that we have with possible future events. What I have outlined here is not an exhaustion of how clicks work or how speculation is achieved through games. Rather, I have highlighted the smallest interaction that generates speculation in its most apparent circumstances. In closing, we can turn to David Elkins’s 1979 essay ‘Science Fiction versus Futurology’, in which he distinguishes the dramatic models of sf, where ‘SF give[s] form to the future and create[s] attitudes for readers to organise ‘action’ in the present’ versus futurology’s logical models that ‘think about’ change and organise ‘knowledge’ for predicting future events’ (Elkins 20). By pitting sf against the data analysis claims of the futurists, Elkins suggests that we can understand the true value of sf as a form of social fiction: ‘SF makes no propositions about the future in which its events are situated; it is a symbolic The click of a button 489 construct of a future’ (20). For both modes of speculation, this claim towards building out a world from a set of experiences is true, and I argue that they are more intensive in that they are specifically activated by the interactions of the click. The futures to which each of these games give form are radically different: one is plotted out to completion and then discovered, and the other could have been anything at all, despite ultimately ending in collapse and the dissolution of the ability of the click to ever happen again. We can never click Impetus again. Our investments and interactions annihilated it. It is the commitment to the future, to events emanating from the future, towards which sf orients our attention. When this is in the form of the game, with interactive mechanisms that can bring or defer the future in methodical ways, our modes of exploring the potential for the relationship between sf and games become more robust. At the opening of this essay, I evoked Csicsery-Ronay’s yearning for an sf method for understanding how video games function. In the analysis of two games, I have not endeavoured to provide a full method for how all video games work when viewed through their relationship with sf. Instead, I have attempted to show how one mode of interaction that a player has with a game, the click, can then provoke speculation within that player. This, I believe, is an important avenue of inquiry in the future study of games and sf. It is imperative to understand how our modes of interaction with video games function in the micro so that one can then understand how these modes of interaction compile, configure and assemble into larger forms of the sf genre within games. It is only in this way that we can understand what video games uniquely contribute to sf’s quality of speculation rather than simply extolling the virtues of shared affinities for spaceships, heroes and concerns about what makes us human. Discovering what makes speculation in a game different from speculation in a novel, film or comic book is the endeavour that sets itself in front of us, and my hope is for future scholarship to take up these ideas that press them to their limit. If there are serious games, queer games and experimental games, among a plethora of other kinds, can there be said to be a distinct strain of work that could be thought of as speculative games? Works cited Anthropy, Anna and Naomi Clark. A Game Design Vocabulary: Exploring the Foundational Principles Behind Good Game Design. Upper Saddle River: Addison-Wesley, 2014. Apperley, Thomas H. ‘Genre and Game Studies: Toward a Critical Approach to Video Game Genres’. Simulation & Gaming 37.1 (2006): 6–23. 490 Cameron Kunzelman Bryant, Levi, Nick Srnicek and Graham Harman. ‘Towards a Speculative Philosophy’. The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and Realism. Melbourne: re.press, 2011. 1–18. Csicsery-Ronay, Jr, Istvan. The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction. Middletown: Wesleyan UP, 2008. Delany, Samuel R. ‘To Read The Dispossessed’. The Jewel-Hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction. Elizabethtown: Dragon Press, 1977. 239–308. Donovan, Tristan. Replay: The History of Video Games. East Sussex: Yellow Ant, 2010. Elkins, Charles. ‘Science Fiction versus Futurology: Dramatic versus Rational Models’. Science Fiction Studies 6.1 (1979). 20–31. Gill, R.B. ‘The Uses of Genre and the Classification of Speculative Fiction’. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 46.2 (2013). 71–85. Graetz, J.M. ‘The Origin of Spacewar’. www.talisman.org/~erlkonig/misc/spacewar.html. Accessed 4 Sep 2017. Hume, David. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Johan, Dominik. ‘Impetus’ (2013). https://web.archive.org/web/20130828225605/https:// dominikjohann.tumblr.com/post/59611971605. Accessed 4 Sep 2017. Johan, Dominik, Jan Oelze and Jeremy Lonien. ‘Impetus’. Ludum Dare 27: 10 Seconds (2013). www.ludumdare.com/compo/ludum-dare-27/?action=preview&uid=27544. Accessed 4 Sep 2017. Juul, Jesper. Half-Real: Video Games Between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005. Krzywinska, Tanya and Esther McCallum-Stewart. ‘Digital Games’. The Routledge Guide to Science Fiction. Eds. Mark Bould, Andrew M. Butler, Adam Roberts and Sherryl Vint. New York: Routledge, 2009. 350–61. Lewis, Chris, Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Jim Whitehead. ‘Motivational Game Design Patterns of “Ville Games”’. Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (2012). 172–9. Lo, Claudia. ‘Everything Is Wiped Away: Queer Temporality in Queers in Love at the End of the World’. Camera Obscura 32.2 (2017): 185–92. Meillassoux, Quentin. After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency. Trans. Ray Brassier. New York: Continuum, 2008. —. Science Fiction and Extro-Science Fiction. Trans. Alyosha Edlebi. Minneapolis: Univocal, 2015. Murray, Janet. ‘Toward a Cultural Theory of Gaming: Digital Games and the Co-Evolution of Media, Mind, and Culture’. Popular Communication 4.3 (2006): 185–202. Schrank, Brian. Avant-Garde Videogames: Playing with Technoculture. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2014. Sharp, Jon. Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2015. Suvin, Darko. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. New Haven: Yale UP, 1979. Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Harper, 1960. About the contributors Gerry Canavan is Associate Professor in the Department of English at Marquette University. He is the author of Octavia E. Butler (2016) and the co-editor of the forthcoming Cambridge History of Science Fiction. Nathaniel Comfort is Professor of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Univeristy. He writes on genes, genomes and the social meanings of heredity, for both scholarly and lay audiences. Catherine Constable is Professor in the Department of Film and Television Studies at the University of Warwick. She is on the editorial board of Film-Philosophy and co-editor of the series Film Studies and Philosophy with Palgrave-Macmillan. Her monographs include Postmodernism and Film: Rethinking Hollywood’s Aesthetics (2015) and Adapting Philosophy: Jean Baudrillard and The Matrix Trilogy (2009). Kirsten Dillender is a PhD student at the University of Illinois interested in sf as well as literature and the environment, theory and gaming/memes. Johan Hallqvist is a PhD candidate in ethnology in the Department of Culture and Media Studies & Umeå Centre for Gender Studies at Umeå University. He is interested in exploring human–technology relationships both in fiction and in the fields of eHealth and digital health technologies. Everett Hamner is Associate Professor of English at Western Illinois University. His writing about Orphan Black may also be found in Editing the Soul: Science and Fiction in the Genome Age (2017) and online at the Los Angeles Review of Books. David M. Higgins is the Speculative Fiction Editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books. He teaches in the English department at Inver Hills College in Minnesota, and his research examines imperial fantasies in postwar American culture. He has published in journals such as American Literature, Science Fiction Studies, Paradoxa and Extrapolation, and his work has appeared in edited volumes such as The Cambridge Companion to American Science Fiction. Cameron Kunzelman is a PhD candidate in Moving Image Studies at Georgia State University. His dissertation is about the aesthetic categories through which humans wrestle with their own finitude. Jennifer L. Lieberman is Associate Professor of American Literature and Culture at the University of North Florida. She is the author of Power Lines: Electricity in American Life and Letters, 1882–1952 (2017), as well as several articles on technology, literature and culture. Giorgina Paiella is a PhD student in the English Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on the long eighteenth century, the digital humanities, cognitive science, and gender studies, with a particular focus on the intersection of gender and automation and artificial intelligence. Science Fiction Film and Television 11.3 (2018), 519–20 © Liverpool University Press ISSN 1754-3770 (print) 1754-3789 (online) https://doi.org/10.3828/sfftv.2018.31 Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.