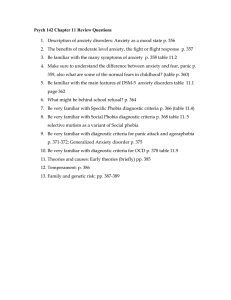

Anxiety Disorders: GAD & Panic Disorder - DSM-5 Criteria

advertisement

Anxiety Disorders Fear vs. Anxiety Fear is a response to external threat. Or otherwise is the emotional response for certain danger or threat. Anxiety it is an internal state, focused very much on anticipation of danger. It resembles fear but occurs in the absence of an identifiable external threat, or it occurs in response to an internal threatening stimulus. Or otherwise is the emotional response for uncertain danger or threat. Anxiety disorders in primary care settings • Anxiety disorders are commonly encountered in clinical practice. In most studies of primary care settings (e.g., Lowe et al. 2008), anxiety disorders (10%-15% of patients) are more common than depressive disorders (7%-10% of patients). In a general psychiatric outpatient practice, anxiety disorders will comprise up to 40% of new referrals. • Much of the treatment of anxiety disorders can be successfully carried out by the primary care treatment provider (e.g., family doctor or internist). The psychiatrist usually plays a consultative role or manages the patients who are most difficult to treat. Epidemiology • Among the mental disorders, anxiety disorders are the most prevalent conditions in any age category. • They are associated with substantial cost to society due to disability and loss of work productivity. • Emerging evidence shows that anxiety disorders are associated with increased risk of suicidal behavior (Sareen 2011). Approximate lifetime and 12-month prevalence, gender ratio, and median age at onset for anxiety disorders in the U.S. general population Disorder Panic disorderᵃ Agoraphobiab Social anxiety disorder Generalized anxiety disorder Specific phobia Lifetime 12-month prevalence prevalence (%) (%) Median age Gender ratioat onset (F:M) (years) 3.8 2.5 10.7 2.4 1.7 7,4 1.8:1 1.8:1 1.4:1 23 18 15 4.3 2.0 1.8:1 30 15.6 12.1 1.2 1.5:1 Separation anxiety disorder 6.7 1.6:1 16 Common risk factors for the most of the anxiety disorders: • Female sex, • younger age, • single or divorced marital status, • low socioeconomic status, • poor social supports, • low education, • Stressful life events and childhood maltreatment are strong risk factors for anxiety disorders Comorbidity Comorbidity is the presence of one or more additional diseases or disorders co-occurring with a primary disease or disorder • Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with other mental disorders, personality disorders, and physical health conditions. • Over 90% of persons with an anxiety disorder having lifetime comorbidity with one or more of these disorders • Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with other conditions often leads to poorer outcomes and affects treatment. • Mood and substance use (including nicotine and alcohol) disorders also commonly co-occur with anxiety disorders. Comorbidity • Physical health conditions are also common among patients with anxiety disorders (Sareen et al. 2006). Among the comorbid physical health conditions, the most prevalent are 1. cardiovascular disease, 2. respiratory illness (e.g., asthma) 3. arthritis 4. migraines • The onset of a serious physical illness might trigger the onset of an anxiety disorder, or conversely, anxiety and avoidance might lead to physical health problems. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by nervousness, somatic symptoms of anxiety, and worry. What distinguishes GAD is the multifocal and pervasive nature of the worries. Individuals with GAD have multiple domains of worry; these might include: finances, health (their own and that of their loved ones), safety, and many others DSM-5 Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder A. Excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation), occurring more days than not for at least 6 months, about a number of events or activities (such as work or school performance). B. The individual finds it difficult to control the worry. DSM-5 Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder C. The anxiety and worry are associated with three (or more) of the following six symptoms (with at least some symptoms having been present for more days than not for the past 6 months): 1. Restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge. 2. Being easily fatigued. 3. Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank. 4. Irritability. 5. Muscle tension. 6. Sleep disturbance (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless, unsatisfying sleep). DSM-5 Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder • The anxiety, worry, or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. • The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism). DSM-5 Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder The disturbance is not better explained by another mental disorder -e.g., anxiety or worry about having panic attacks in panic disorder, - negative evaluation in social anxiety disorder [social phobia], - contamination or other obsessions in obsessive-compulsive disorder, - separation from attachment figures in separation anxiety disorder, - reminders of traumatic events in posttraumatic stress disorder, - gaining weight in anorexia nervosa, - physical complaints in somatic symptom disorder, - perceived appearance flaws in body dysmorphic disorder, - having a serious illness in illness anxiety disorder, or - the content of delusional beliefs in schizophrenia or delusional disorder). GAD is encountered much more frequently by primary care physicians and other medical practitioners than by psychiatrists (Kroenke et al. 2007) GAD typically presents with somatic symptoms for which sufferers seek help in the primary care setting: - headache - back pain and other muscle aches - gastrointestinal distress - Insomnia is another common complaint in GAD for which patients may seek help in primary care. Here more common initial insomnia (difficulty falling or staying asleep) - GAD-like symptoms can be caused by some physical ailments (e.g., hyperthyroidism) and substances (e.g., excess caffeine use; stimulants) Etiology • Twin studies suggest that GAD is influenced by genetic factors that overlap extensively with those for the personality trait neuroticism (Hettema et al. 2004) 1. Individuals who score high on neuroticism are more likely than average to be moody and to experience such feelings as anxiety, worry, fear, anger, frustration, envy, jealousy, guilt, depressed mood, and loneliness. 2. People who are neurotic respond worse to stressors and are more likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. Neuroimaging studies in GAD: There is some evidence of failure of anterior cingulate activation and connectivity with the amygdala during implicit regulation of emotional processing in GAD (Etkin et al. 2009). Panic Disorder (soldier's heart; neurocirculatory asthenia) • Panic disorder is mainly consisting of a panic attacks. • Panic attacks are sudden, at least sometimes unexpected episodes of severe anxiety, accompanied by an array of physical (e.g., cardiorespiratory, motoneurological, gastrointestinal, and/or autonomic) symptoms • These attacks are extremely frightening, particularly because they seem to occur out of the blue and without explanation. • Patients with panic disorder often report extreme fatigue after experiencing an attack (not included as part of current diagnostic criteria) DSM-5 Criteria for Panic Disorder Recurrent unexpected panic attacks. A panic attack is an abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that reaches a peak within minutes, and during which time four (or more) of the following symptoms occur: Note: The abrupt surge can occur from a calm state or an anxious state. 1. Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate. 2. Sweating. 3. Trembling or shaking, 4. Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering. 5. Feelings of choking. 6. Chest pain or discomfort. DSM-5 Criteria for Panic Disorder 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Nausea or abdominal distress. Feeling dizzy, unsteady, light-headed, or faint. Chills or heat sensations. Paresthesias (numbness or tingling sensations). Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself). 12. Fear of losing control or “going crazy.” 13. Fear of dying. DSM-5 Criteria for Panic Disorder B. At least one of the attacks has been followed by 1 month (or more) of one or both of the following: 1. Persistent concern or worry about additional panic attacks or their consequences (e.g., losing control, having a heart attack, “going crazy”). 2. A significant maladaptive change in behavior related to the attacks (e.g., behaviors designed to avoid having panic attacks, such as avoidance of exercise or unfamiliar situations). C. The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism, cardiopulmonary disorders). DSM-5 Criteria for Panic Disorder D. The disturbance is not better explained by another mental disorder • the panic attacks do not occur only in response to feared social situations, as in social anxiety disorder; • in response to circumscribed phobic objects or situations, as in specific phobia; • in response to obsessions, as in obsessive-compulsive disorder; • in response to reminders of traumatic events, as in posttraumatic stress disorder; • in response to separation from attachment figures, as in separation anxiety disorder). Over time the individual may curtail many activities to prevent panic attacks from occurring in such situations. It is this pervasive phobic avoidance—which carries the diagnostic label agoraphobia—that often leads to the extensive disability seen with panic disorder. Panic disorder and general medical conditions Because panic disorder mimics numerous medical conditions, patients often have increased utilization of health care, including physician visits, procedures, and laboratory tests (Kroenke et al. 2007). Persons with panic disorder frequently have the belief that their intense somatic symptoms are indicative of a serious physical illness (e.g., cardiac or neurological). This is particularly true early on in the course of their illness and in situations where they fail to get good care that includes appropriate diagnosis and education about their condition. Panic disorder and comorbid medical problems Panic attacks (and, when recurrent, panic disorder) can occur as a direct result of common conditions such as hyperthyroidism and caffeine and other stimulant (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine) use/abuse, and more rarely with disorders such as pheochromocytoma or partial complex seizures. To "rule out" for such conditions : • A thorough medical history, • physical examination, • routine electrocardiogram, • thyroid-stimulating hormone blood level, • urine or blood drug screen are sufficient as a first-pass "rule out" for such conditions. Panic disorder and comorbid medical problems Additional tests may be indicated if: 1. frequent palpitations indicating the need for a Holter monitor, echocardiogram, and/ or cardiology consultation; 2. profound confusion during or after attacks indicating the need for an electroencephalogram and/or neurology consultation). The physician have to revisit the medical differential diagnosis if: 1. the course of illness changes, 2. if symptoms become atypical, 3. the patient does not respond well to standard treatments Etiology Genetics. Twin studies suggest that panic disorder is moderately heritable (~ 40%) (Gelernter and Stein 2009). F Panic disorder, like other psychiatric disorders, is a complex disorder with multiple genes conferring vulnerability through as-yet largely undetermined pathways (Manolio et al. 2009; Smoller et al. 2009). Etiology Neurobiology. Beginning in 1967 with Pitt's observation that hyperosmolar sodium lactate provoked panic attacks in patients with panic disorder but not in control subjects (Pitts and McClure 1967), Agents with disparate mechanisms of action such as caffeine, isoproterenol, yohimbine, carbon dioxide, and cholecystokinin (CCK) had similar abilities to provoke panic in patients with panic disorder but not in control subjects (RoyByme et al. 2006). Many of these neurobiological "challenge" agents have been thought to have specific effects on the brain's fear circuits, which are believed to function aberrantly in patients with panic disorder. The amygdala has a crucial role as an anxiety way-station that mediates incoming stimuli from the environment (thalamus and sensory cortex) and stored experience (frontal cortex and hippocampus), thereby affecting the anxiety and panic response by stimulating various brain areas responsible for key panic symptoms. Etiology Psychology Learning theory postulates that factors that increase the salience of bodily sensations are central to the onset and maintenance of panic disorder. The heightened state of interoceptive attention (attention to internal sensations) that primes the individual to experience panic attacks and to be intensely frightened by them when they occur. "Fear of fear" develops after the initial panic attacks and is believed to be the result of interoceptive conditioning (conditioned fear of internal cues such as pounding heart) and the subsequent misappraisal of these internal cues as indicating something threatening or dangerous (e.g., loss of control; heart attack or stroke) (Bouton et al. 2001). Agoraphobia Agoraphobia literally, in Greek, means "fear of the marketplace." Agoraphobia refers to marked fear or anxiety of the situations in which patient can stay alone without possibility to get help from companion or from other close person. Patient afraid that certain symptoms, like dizziness, heart racing, trouble concentrating, occur in these situations. The agoraphobic situations are actively avoided, require the presence of a companion, or are endured with intense fear or anxiety.: DSM-5 Criteria for Agoraphobia A. Marked fear or anxiety about two (or more) of the following five situations: 1. Using public transportation (e.g., automobiles, buses, trains, ships, planes). 2. Being in open spaces (e.g., parking lots, marketplaces, bridges). 3. Being in enclosed places (e.g., shops, theaters, cinemas). 4. Standing in line or being in a crowd. 5. Being outside of the home alone. DSM-5 Criteria for Agoraphobia B. The individual fears or avoids these situations because of thoughts that escape might be difficult or help might not be available in the event of developing panic-like symptoms or other incapacitating or embarrassing symptoms (e.g., fear of falling in the elderly; fear of incontinence). C. The agoraphobic situations almost always provoke fear or anxiety. D. The agoraphobic situations are actively avoided, require the presence of a companion, or are endured with intense fear or anxiety. E. The fear or anxiety is out of proportion to the actual danger posed by the agoraphobic situations and to the sociocultural context. F. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance is persistent, typically lasting for 6 months or more. DSM-5 Criteria for Agoraphobia G. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. H. If another medical condition (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, Parkinson’s disease) is present, the fear, anxiety, or avoidance is clearly excessive. I. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance is not better explained by the symptoms of another mental disorder—for example: • the symptoms are not confined to specific phobia, situational type; • do not involve only social situations (as in social anxiety disorder); • and are not related exclusively to obsessions (as in obsessive-compulsive disorder), • perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance (as in body dysmorphic disorder), • reminders of traumatic events (as in posttraumatic stress disorder), or fear of separation (as in separation anxiety disorder). Social Anxiety Disorder Social anxiety disorder, also known as social phobia, is characterized by a marked fear of social and performance situations that often results in avoidance. The concern in such situations is that the individual will say or do something that will result in embarrassment or humiliation. The core fear in SAD is fear of negative evaluation—that is, the belief that when in situations where evaluation is possible, the individual will not measure up and will be judged negatively (Hofmann et al. 2009). Despite the extent of suffering and impairment associated with social phobia, few individuals with the disorder seek treatment, and often only after decades of suffering. DSM-5 Criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia) A. Marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situations in which the individual is exposed to possible scrutiny by others. Examples include social interactions (e.g., havng a conversation, meeting unfamiliar people), being observed (e.g., eating or drinking), and performing in front of others (e.g., giving a speech). Note: In children, the anxiety must occur in peer settings and not just during interactions with adults. B. The individual fears that he or she will act in a way or show anxiety symptoms that will be negatively evaluated (i.e., will be humiliating or embarrassing; will lead to rejection or offend others). DSM-5 Criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia) C. The social situations almost always provoke fear or anxiety. Note: In children, the fear or anxiety may be expressed by crying, tantrums, freezing, clinging, shrinking, or failing to speak in social situations. D. The social situations are avoided or endured with intense fear or anxiety. E. The fear or anxiety is out of proportion to the actual threat posed by the social situation and to the sociocultural context. F. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance is persistent, typically lasting for 6 months or more. G. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. DSM-5 Criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia) H. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition. I. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance is not better explained by the symptoms of another mental disorder, such as panic disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder. J. If another medical condition (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, obesity, disfigurement from burns or injury) is present, the fear, anxiety, or avoidance is clearly unrelated or is excessive. Specify if: Performance only Specific Phobia A key feature of specific phobia is that the fear or anxiety is limited to the phobic stimulus, which is a specific situation or object. DSM-5 has codes for specifying the various types of situations or objects that may be involved: animal, natural environment, bloodinjection-injury situational, and other. DSM-5 Criteria for Specific Phobia A. Marked fear or anxiety about a specific object or situation (e.g., flying, heights, animals, receiving an injection, seeing blood). Note: In children, the fear or anxiety may be expressed by crying, tantrums, freezing, or clinging. B. The phobic object or situation almost always provokes immediate fear or anxiety. C. The phobic object or situation is actively avoided or endured with intense fear or anxiety. D. The fear or anxiety is out of proportion to the actual danger posed by the specific object or situation and to the sociocultural context. E. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance is persistent, typically lasting for 6 months or more. F. The fear, anxiety, or avoidance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. DSM-5 Criteria for Specific Phobia G. The disturbance is not better explained by the symptoms of another mental disorder, including: • fear, anxiety, and avoidance of situations associated with panic-like symptoms or other incapacitating symptoms (as in agoraphobia); • objects or situations related to obsessions (as in obsessivecompulsive disorder); • reminders of traumatic events (as in posttraumatic stress disorder); • separation from home or attachment figures (as in separation anxiety disorder); • or social situations (as in social anxiety disorder). DSM-5 Criteria for Specific Phobia Specify if: Code based on the phobic stimulus: 300.29 (F40.218) Animal Natural environment 300.30 (F40.228) Natural environment 300.29 (F40.23x) Blood-injection-injury 300.29 (F40.248) Situational 300.29 (F40.298) Other Specific phobias vs. Normal fears • Specific phobias must be persistent (though this characteristic, of course, depends on the opportunity for exposure to the situation or object), • the fear or anxiety must be intense or severe (sometimes taking the form of a panic attack), • the individual must either be routinely taking steps to actively avoid the situation or object or be intensely distressed in its presence. • the fear and/or avoidance in specific phobias must be disproportionate to the actual danger posed by the situation (Craske et al. 2009). Treatment of Anxiety Disorders General Approach • Treatment of anxiety disorders can be extremely gratifying for clinicians because anxiety disorders tend to respond well to psychological and pharmacological treatments. • Most patients with anxiety disorders can be well managed in the primary care setting, with only the more difficult-to-treat cases necessitating care in the mental health specialty setting. • Most patients prefer treatment of anxiety with psychotherapy alone or in combination with medications (Roy-Byrne et al. 2010). However, evidence based psychotherapies administered by therapists well trained and experienced in those psychotherapies may not be readily accessible by all patients in all settings. • Thus, medication treatment, which is more often available and covered by insurance, frequently becomes the de facto treatment of anxiety disorders. Algorithm for the treatment and management of anxiety disorders Cognitive-Behavior Therapy Among the psychosocial interventions for anxiety disorders, CBT has the most robust evidence for efficacy and has been delivered in a variety of formats. CBT strategies for the various anxiety disorders differ somewhat in their focus and content, but despite this disorder-specific tailoring they are similar in their underlying principles and approaches (Craske et al. 2011). All CBT strategies have the following core components: psychoeducation, relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, and exposure therapy. • Psychoeducation involves having the patient read material about the normal and abnormal nature of anxiety that enhances their understanding of the sources and meanings of anxiety. • Relaxation training involves systematic desensitization, patients gradually but in increasingly more challenging situations face the phobic stimuli that make them feel anxious. Other techniques in CBT include relaxation training through deep muscle relaxation and/or breathing management. • Exposure therapy. Over the course of the therapy the patient would slowly face the anxiety-provoking situations and learn that if she stays in the situation long enough, the anxiety resolves. • Cognitive restructuring. The cognitive model of anxiety disorders proposes that people with these disorders overestimate the danger in a particular situation and underestimate their own capacity to handle the situation. • People with anxiety disorders often have catastrophic automatic thoughts in triggering situations. • Patients are taught to become aware of these thoughts that precede or cooccur with their anxiety symptoms, and they learn to challenge these thoughts and change them. Pharmacotherapy (general issues) • Pharmacotherapy is a good option for many patients with anxiety disorders, either in combination with CBT or as a stand-alone treatment (Ravindran and Stein 2010) • Providing patients with material that describes their symptoms, discusses at an appropriate level of depth the theoretical underpinnings of their disorder(s), and begins to make them aware of treatment options can be the most important therapeutic intervention the clinician makes (see psychoeducation). • Exposure instructions and practice can be readily incorporated into everyday pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders. Patients should be instructed that whereas their antianxiety medication(s) are intended to reduce their spontaneous and anticipatory anxiety, it is important that they begin to face situations that have made them fearful in the past in order to learn that they are safe and that they can be successfully negotiated. Pharmacotherapy (general issues) • The medication classes with the best evidence of efficacy and (when used properly) safety for the anxiety disorders are the antidepressants and the benzodiazepine anxiolytics. • The antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) • There are currently six different SSRIs available for clinical use in the United States: fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, and escitalopram. • There are currently four SNRIs available for clinical use in the United States: venlafaxine ER, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran. • Experts usually recommend an initial trial of an SSRI beginning with the lowest available dose, given that patients with anxiety disorders— particularly those with panic disorder, who attend to and fear physiological sensations—tend to be sensitive to medication side effects. The dose is then increased gradually, in weekly or biweekly increments, until therapeutic doses are reached. • Time course of response is similar to that in major depression, that is, taking 4–6 weeks to see a clinically meaningful response (though this may occur sooner) and as long as 12–16 weeks to achieve an optimal response. Pharmacotherapy • Benzodiazepines are the best-established pharmacotherapy for treating anxiety that is predictable and limited to particular situations (e.g., specific phobia such as flying phobia; social phobia such as public speaking or other performance anxiety), for which they can be prescribed on an “as needed” basis (el-Guebaly et al. 2010). • Prescription of benzodiazepines on an as-needed basis for unpredictable anxiety (e.g., panic disorder) or chronic anxiety (e.g., GAD) is not recommended. Pharmacotherapy • Nonbenzodiazepine Anxiolytics • Buspirone is a nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytic with efficacy limited to the treatment of GAD. • Gabapentin and pregabalin have somewhat limited evidence for efficacy in treating anxiety disorders, though they are sometimes used as an alternative to benzodiazepines, often as an adjunct to antidepressants. Combining CBT and Pharmacotherapy Although the evidence is limited, several studies suggest that combining CBT and pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders is superior to either alone (Blanco et al. 2010), particularly in children (Walkup et al. 2008).