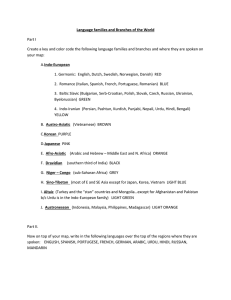

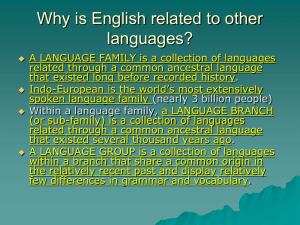

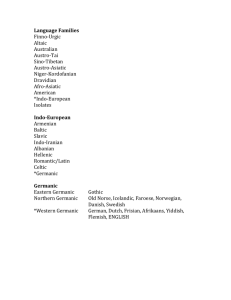

THEME 1. HISTORICAL CONDITIONS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH § 1. ENGLISH AS A GERMANIC LANGUAGE OF THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY Old English developed from the Germanic language which in its turn goes back to the Indo-European language. The common Proto-Indo-European language existed in the 5-2 millennia B.C. In the second millennium B.C. Indo-European split into a number of new languages which gave rise to 12 branches of the Indo-European family: Germanic, Slavic, Baltic, Celtic, Romanic, Greek, Albanian, Armenian, Iranian, Indian, and other extinct languages. Germanic split into the languages of three groups: East-Germanic, North-Germanic and West-Germanic. The East-Germanic group includes only dead languages: Gothic, Burgundian, and Vandalic. Gothic is of great importance for the students of Germanic philology since the oldest Germanic texts were written in this language. It disappeared in the 17th century. The North-Germanic group comprises Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Faroese and Icelandic. The West-Germanic group includes English, German, Dutch, Frisian, Flemish, Yiddish, and Afrikaans spoken in South Africa. The history of English began in the 5th century when the Anglo-Saxon tribes invaded the British Isles. § 2. THE STRUCTURE OF THE OLD ENGLISH VOCABULARY The vocabulary spoken by Anglo-Saxons during the Old English period reflects the stages of the prehistoric development of English. The word-stock of that period consists of three layers: Indo-European, Germanic, and Old English. The words of the Indo-European layer can be found in other Indo-European languages, e.g. Latin, Russian, Ukrainian. The words of the Germanic layer are found in other Germanic languages, e.g. German. The words of the Old English layer appeared in English and cannot be traced to any other IndoEuropean or Germanic language. 2.1. Indo-European layer The words of this layer denote the most basic things of everyday life: terms of kinship, e.g. mother – Ukr. матір; sister – Ukr. сестра; son – Ukr. син; body parts, e.g. back – Ukr. бік; beard – Ukr. борода; brow – Ukr. брова; tooth – Lat. dens, cf. Ukr. дантист; heart – Lat. cor, cf. Ukr. кардіолог; lip – Lat. labium; animals, e.g. swine – Ukr. свиня; plants, e.g. birch – Ukr. береза; tree – Ukr. дерево; colours, e.g. brown – Ukr. брунатний; red – Ukr. рудий 2.1. Indo-European layer verbs, e.g. call – Ukr. голос; eat – Ukr. їсти; sit – Ukr.сидіти; stand – Ukr. стояти; sleep – Ukr. слабий; smile – Ukr. сміятися; separate objects, e.g. field – Ukr. поле; hammer – Ukr. камінь; milk – Ukr. молоко; prepositions, e.g. to – Ukr. до; numerals: ān – Ukr. один; twā, tū, twēgen – Ukr. два; þrī, þrēo, þrīe – Ukr. три; fēower – Ukr. чотири; fīf – Ukr. п’ять; siex, syx – Ukr. шість; seofon – Lat. septem(ber); æht, eaht – Lat. octo(ber); nigon – Lat. novem(ber); tÿn,tien – Ukr. десять, Lat. decem(ber); thousand – Ukr. тисяча. SOME TYPOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE GERMANIC LANGUAGES: The levelling of the IE tense system into past and present. The use of a dental suffix (/d/ or /t/) instead of vowel alternation (ablaut) to indicate past tense. The presence of two distinct types of verb conjugation: weak (using dental suffix) and strong (using ablaut). SOME TYPOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE GERMANIC LANGUAGES (continuation): The use of strong and weak adjectives. The consonant shift known as Grimm’s Law. A number of words (called Common Germanic) with etymologies that are difficult to link to other Indo-European families, but variants of which appear in almost all Germanic languages. The shifting of stress onto the root of the stem. Additional information. The study of the Indo-European layer of the vocabulary helps to determine where the Indo-European people lived. In the 19th century it was customary to assume an Asiatic home for the Indo-European family which was the result of the biblical tradition that placed the garden of Eden in Mesopotamia. However, the facts of various Indo-European languages prompt that the original home for the family was Europe because the languages of this group have common words for ‘winter’ and ‘snow’ which means that the family was in a climate that at certain seasons was at least partly cold. Therefore a European home for the languages of the IndoEuropean family has come to be considered more probable. Most of the proposed locations can be in the district of the Germanic area stretching from central Europe to the steppes of southern Russia and Ukraine. 2.2. Germanic layer The vocabulary of this layer can be divided into two subgroups: - expanding the Indo-European word classes; - names of new phenomena. 2.2.1. Words expanding the Indo-European classes: - terms of distant kinship, e.g. uncle – Germ. der Onkel, aunt – Germ. Die Tante; - body parts, e.g. arm – Germ. der Arm; finger – Germ. der Finger; hand – Germ. die Hand; head – Germ. das Haupt; 2.2. Germanic layer - animals, e.g. bear – der Bär; fox – der Fuchs; calf – das Kalb; - plants, e.g. oak – Germ. die Eiche; lime – Germ. Die Linder (a tree under which trials took place); beech tree – Germ. das Buch (originally pieces of writing were scratched on beechen boards, hence ModE book); - colors, e.g. green – Germ. grün; blue – Germ. blau; - verbs, e.g. drink – Germ. trinken. 2.2.2. Names of new phenomena: spatial terms, e.g. earth, ground, land, sand; temporal names, e.g. week; names of days: Anglo-Saxons were pagans, i.e. they believed in many Gods, and gave their names to days of the week: Sunday – Sun’s day; Monday – Moon’s day; Tuesday – the day of Tiw (the god of war); Wednesday – Woden’s day (the god of wind); Thursday – Thor’s day (the god of thunder, cf. Germ. der Donner “thunder” – Donnerstag); Friday – Frige’s day (the goddess of love, cf. ModE friend); Saturday – Saturn’s day (Roman god of agriculture). Additional note. To be more exact, names of the days of the week should be treated as translation loans, i.e. units created on the pattern of Latin words as their literal translations. They were formed by the substitutions of the name of the corresponding Germanic god for the god of the Romans. For example, Monday, i.e. Moon’s day = Lat. Lunae dies; Tuesday, i.e. Tiw’s day = Lat. Martis dies since the Teutonic God Tiw corresponds to Roman Mars. 2.3. Old English layer These words appeared in Old English and cannot be found in other Indo-European languages though some of them were borrowed by other languages later. The specifically Old English words are bird (OE brid), lord (OE hlāford = hlāf ‘loaf’ + weard ‘keeper’), woman (OE wīf-man) etc. 2.4.1. Latin borrowings comprise three groups: 1) the words introduced by Roman traveling merchants into the common Germanic language; 2) the words adopted during the Roman occupation of the British Isles; 3) the units connected with the introduction of Christianity. Latin borrowings of the common Germanic period denote measures, e.g. pound, mile, money, fruit, e.g. pear, plum, cherry, vegetables, e.g. beet, plant, drinks, e.g. beer, wine, food, e.g. butter, pepper. The words connected with the fortifications built by the Romans are wall, street, port, etc. The Latin borrowings brought with the introduction of Christianity (7th century) are alter, angel, anthem, candle, devil, pope, school etc. 2.4.1. Celtic borrowings Celtic borrowings are very few (about a dozen words): ass, bin, clan, down, iron, tory, whiskey, place-names, e.g. Avon, Dover, Kent, Thames, York, perhaps, London, names of persons, e.g. Arthur (noble), Kennedy (ugly head). The name of the British capital London originates from the Celtic compound noun Llyndūn meaning “a fortress on the hill over the river” (Celtic llyn, “a river” + dūn, “a fortified hill”). § 3. FIRST GERMANIC CONSONANT SHIFT: GRIMM’S LAW Many words of the Indo-European layer have different consonants in related units, cf. tree – Ukr. дерево, to – Ukr. до, call – Ukr. голос; tooth – Lat. dens, cf. Ukr. дантист; heart – Lat. cor, cf. Ukr. кардіолог; hammer – Ukr. камінь. These differences were explained in 1822 by a German philologist, Jacob Grimm. Therefore this set of changes is often called Grimm’s law. Grimm’s law The changes are systematically revealed if we compare Ukrainian and English numerals: два – two: d → t; три – three: t → θ; п’ять – five: p → f. The comparison of два and two suggests that the IndoEuropean voiced plosives (stops) d, b, g developed into the Germanic voiceless plosives t, p, k, e.g. два – two, яблуко – apple, голос – call. It is the first act of Grimm’s law. Grimm’s law The comparison of три – three and п’ять – five reveals that the Indo-European voiceless plosives t, p, k became Germanic fricatives θ, f, h, e.g. три – three, п’ять – five, корова – horn. It is the second act of Grimm’s law. The third act of Grimm’s law is not reflected in modern languages. It concerns the development of the IndoEuropean aspirated voiced plosives bh, dh, gh into the Germanic voiced plosives b, d, g, e.g. Skrt. bhratar – ModE brother. These developments explain similar consonants in the English and Ukrainian words back and бік; beard and борода; brow and брова etc.