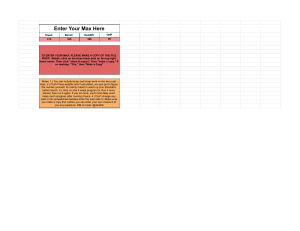

PEAK STRENGTH COMPETITIVE PERFORMANCE ROADMAP BROMLEY TABLE OF CONTENTS Pg. 10 Mass Pg. 21 Specialization Pg. 29 The Base/Peak Model Pg. 38 Squatting, Pressing and Pulling Pg. 46 Variations and Accessory Pg. 68 Organizing the Training Week Pg. 82 Pacing Efforts and Recovery Pg. 92 Methods of Progression Pg. 103 Finishing the Peak: Contest Prep Pg. 111 From the Ground Up: Novice Pg. 119 From the Ground Up: Intermediate Pg. 130 From the Ground Up: Advanced Pg. 141 Advanced Fatigue Techniques Pg. 150 GPP Workouts Dedicated to my beautiful wife, Laura, who surprises me daily with her care and affection, and who belched on the couch as I was writing this. INTRODUCTION My first book, Base Strength, was dedicated to the fundamentals of programming, specifically the century-old principle of progressive overload. The rule states that, for continued growth, stress has to continue increasing over time. Think of a new construction worker struggling with the demands of moving equipment and loading supplies every week; after months of extreme fatigue, they eventually find themselves at a point where work becomes 'just another day'. And just like a construction worker does not continue to gain muscle and endurance from the same old work days, a lifter will not continue to grow from the same exercises done at the same weight and with the same effort. So, for continued growth, stress needs to progress as we progress. The idea has been around for a very long time and is largely known; that is not why I wrote the book. I wrote it because I saw a need for a laypersons guide to the less talked about rules around progressive overload. For all of the texts and e-books that saturate lifting culture, there weren't more than a few publications that could serve as an easy guide for what those rules were and how to implement them in a way that moves the lifter forward while avoiding overtraining or injury. Most trainees learn early on that 'doing more' is vital for a successful training career. No pain, no gain. Better than yesterday. One more rep. Cliche and misleading as these phrases are, effort is actually a powerful tool for growth, so much so that it can make up for huge holes in a training program. But if the only gym wisdom one has to go off of is that growth comes from monumental efforts that only go up over time, the result is months (or years) spent doing too much of the same work with no break, no rest, no reset. The outcome, which many of you have surely experienced at some point, is the heart break and existential angst that comes from pushing through hundreds of hours of soul-crushing work only to end up pretty much where you started. In pulling apart the layers of intelligent program organization, Base Strength combined the principles of specificity, recovery and novelty into some easy workarounds. The Base/Peak dynamic was introduced, which was just an easy visual model to help conceptualize what periodization has been doing all along. With Base Strength, I compared and contrasted a lot of different methods to show the important ways that they were similar, isolating and demystifying the raw elements of programming in the process. These topics shouldn't be thought of as some excessively complex voodoo; the dots actually connect rather nicely once you frame them the right way. Now, with this book, I want to shed some light on how to use those raw elements to commit to a method over a training career. Every lifter is in the process of driving through a decades-long road trip and I often start the writing process by thinking "if I could go back to the start and hand myself a map, what would I have written on it?". The big one is how much training has to change as you move from untrained and unskilled to strong and conditioned. Novices often use their quick gains to assure themselves that they've 'figured it out', unaware that those same tactics stop working right around the time your rapid growth has led you to believe that World Strongest Man is just a few years away. This book would be useful enough if it just explained how to follow a template but, if avoiding slowdowns and eventually becoming competitive is a real goal for you, a template by itself won't do. My real aim here is to go deeper by using this particular template as a case study in how one moves from the bumper cars into the Daytona 500. I'm taking this opportunity to write a map for you that I wish I had myself, to detail that journey by putting a marker at every lane change and pit stop. I could have surely used any of the other programs listed at the back of Base Strength for such a case study, especially since many of them are close to or derivative of common programs out there today. Of those 10 templates, Bullmastiff stood out to me and not just because of the name (it sounded cool and, more importantly, I love dogs). I chose it because this approach addresses some issues common in today's recreational lifter. It works well enough as a blanket template but, more importantly, it goes against the grain of a lot of modern pop-training programs that trade proven fundamentals for unnecessary complexity and increased dogma. I had kicked around the idea of dedicating whole books to some of these templates but I never wanted to sell something that could be called a 'system'. When coaches and writers in this field commit to creating content for a living, they survive by standing out and that only happens with effective branding. Many will do this by building some universe of training methods that revolves around one particular ideology. The problem is that dogma takes root in these systems like termites in your walls. It is an entirely self-serving feature; it exists to promote the ideology rather than to benefit the lifter. Grow using just the big 3. Grow using everything but the big 3. Max every week. Squat every day. 5s, 5s and more 5s. As valid as any one of these approaches might be, they have all been present in some system that arbitrarily fixes them to the wall and doesn't allow them to move. These systems produce publication after publication on how the rest of your training decisions should spin, twist and stretch so that this one variable remains a constant center of this universe. It is born out of a financial incentive to attract more disciples and sell more product. Now, there's not a thing wrong with branding, marketing or profit, but we need to be aware of those biases when we are being told something is true, especially when there is insistence that it is true at the expense of everything else. Many of these approaches are proven enough, having led to plenty of stretched sleeves and bent barbells. But all of them represent a way, not the way. I said all that to say this: the templates used to drive these principles home represent a way. Sure, it's a way that has led to ample growth in newbies and world champions alike and it's a way that I prefer over some of the others. More importantly, it's a way that is limited the same way all other methods are: it only works as well as it solves a problem for the individual running it. By using Bullmastiff as the template, I'm promoting a flavor of training that doesn't trade physical development for pure sport specificity. It includes work and technical practice across all major barbell lifts, pressing, squatting and pulling but also uses a lot of variations and isolation movements. It incorporates a wide range of repetitions for many sets, building up a high level of fatigue in each workout. It is a ton of work and you will be sore. This approach takes inspiration from the old-school, the era that existed before watered-down interpretations of Soviet periodization models dominated modern lifting culture. Recreational lifters in the 1940s, 50s and 60s weren't being water- boarded with training information. They didn't have the luxury to waste countless hours online, debating the validity of trivia gotten from third hand sources. They learned in the gym, using few basic principles that had been passed on from the old timers, and they used their training hours to best mold those principles to themselves with simple trial and error. Soviet data collection still represents the best of what we have for finding best practices over a large population, specifically a population where every participant was pre-selected for their talent and where only a few athletes out of dozens need to survive the system in order to collect their medals. However, it is known by most sports scientists who also spend time in the field, training and coaching, that formal academic science is behind the curve. Way behind. For finding what causes consistent growth in the individual while prioritizing longevity and sustainability, the 'old-school' non-academic approach is about as empirical as it gets. Many of the greats were directly made by this approach. We are talking monsters of decades past who set records by following some of the simplest methodologies one can imagine. The Base progression cycle for Bullmastiff is actually inspired by some familiar wave cycling schemes along with an autoregulation trick made famous by 70s powerlifting phenom, Doug Young. Everything I'm presenting here meets 3 key criteria that must be met for me to sell an idea as the real deal: I have to have had personal success with it myself, personal success with my trainees and (the big one) there has to be a large consensus of support among top performing coaches and lifters. So, I'm starting us off with our feet grounded on the firm cement laid by a century of training wisdom and my own trial and error. With that minimum standard met, we can start building our road-map. MASS For lifters throughout the last few centuries, there was nothing more obviously essential to the pursuit of strength and performance than growing muscle mass. That still might be obvious to some, but increased popularity and changing societal priorities have influenced the spirit of lifting culture to shift. Recreational lifting competitions usually default into a 'rock-star summer camp' type of experience, where a minimal amount of equipment and experience along with an entry fee gets you a ticket to feel like an athlete for a day. Now, amateur contests are a vital way for competitive hopefuls to get their feet wet but the lack of hierarchy and standards (which seem to be present in every other discipline besides strength sports) has led to a 'customer is always right' mentality that has had a wide sweeping effect on the very concept of competition and what growth and education means in that context. In our modern era of consumer culture run amok, new lifters often select their path based on their own preconceived notions about the way things work. This is just like a middle-school student crafting their own syllabus. An increase in the number of competitive divisions in the sport of powerlifting has led novice (smaller) lifters to focus on smaller weight classes, as if the real goal isn't to transform your physique and move your potential for strength up to the next solar system but instead to stay as light as possible. 135lb males of average height no longer see themselves as being light because they are undertrained but rather as natural featherweights, already half way to their spot at the top of the least populated weight classes. This mentality is lazy and universally a byproduct of the fear many feel when they see a mountain that looks too big to climb. Where one might logically think "it's time to get better at climbing", many settle for walking around base camp and calling it the same thing. It would be enough to criticize any philosophy that aims to make gratification immediate by moving the goal posts closer but it doesn't even get you closer to the goal posts once you've moved them. Example: If I were to train a kid who stood 5'9" at a buck-fifty-five, I would typically get push-back if I told him to up his calories and aim to gain 10-15lbs, even though there is no likely path that would lead a typical trainee at that height to a competitive total without getting to at least the 200lb range. The best 132lb lifter was Lamar Gant. He was 5'1". On the other end of the spectrum, 6'5" represents a typical height of heavyweight strongmen while 5'9" to 6'1" represents the typical stature of the most dominant 231lb strongmen. Potential success in a weight classes is determined largely by the height and frame of the lifter. Reaching an optimal weight for your frame takes a ton of time and training; it sure isn't based off how you woke up the day you decided to get a gym membership. The point is, we all begin our journey under-muscled. Every lifter needs more mass and getting enough of it is extremely difficult. You won't get a license if you have a fear of dribing and you won't build a base if you have a phobia of mass. Often these smaller white-belt lifters cite the grotesque physiques of the world's best heavyweights for why weight gain is an unreasonable goal. I've responded to numerous comments that go something like, "Not everyone wants to weigh 330lbs!", as if upping your training volume and protein intake for the next 3 months will result in some "Freaky Friday: Olympia Edition" rather than a pound or two of muscle and a modest squat PR. Getting accidentally too big is like getting accidentally too rich; it's not an actual problem that anyone has. No one suddenly turns into a 280lb bodybuilder. The haul from 160 to 200 is hard enough; bridging the gap from 250 to 260 takes next level planning and patience. That exceptional size is deliberate and requires several years of, as Dorian Yates put it, living like a monk. Young female lifters face a more insidious problem since the aversion to muscularity is a byproduct of persistent cultural norms. Thank God that has changed in the 20 years I've been at this. Where muscular women were universally regarded as an aberration, now there is a push from men and women alike to normalize the perception of the female body as a competitive machine. Volleyball, gymnastics, weightlifting, Crossfit, swimming and strongman all tell the exact same story: strong women have muscle. The decades-long influence of smooth, flat shapes presented by do-nothing runway models is now being replaced by the edges and shadows created by elite athletic performers. If you are a female who is worried about losing femininity, know that you will never add a single ounce of muscle that you didn't intend to put there. If you are worried about becoming masculine, know that big brass balls look good on everybody. One of my greatest joys was watching my wife evolve in the sport of strongman over the last 5 years. When she started, she couldn't deadlift her body weight off the floor; now she is preparing for her second go at Worlds. In the first couple of years training, she experienced substantial growth in her shoulders and arms, partly due to a genetic predisposition, partly due to expert programming *ahem*. Every time I hear apprehension from a female lifter about increasing muscle mass, I think of every sleeveless blouse my wife gleefully modeled in front of the mirror, I think of every time a woman has stopped her on the street to compliment her and I think of every bit of confidence she has gained in her strength, resolve and deadliness. To the women reading this, I hope all of that for you. Everyone should stop right now and find a role model, some lifter or athlete you wouldn't mind swapping bodies with. Use the internet to pull up their stats: height, weight, body composition. Compare yourself. How much muscle do you need go gain to look like them? 10? 20? 50? After the newbie gains wear off, even 5lbs might take a year to put on. Then look at 5lbs of meat on a butcher block and ask if you can afford to 'hold back' on mass gains. Without a doubt, the most important thing at early stages of training is the even accumulation of muscle over your entire frame. That is best done with a lot of repeating sets with sub-maximal loads in the compound barbell movements and no shortage of targeted isolation work we generally describe as 'bodybuilding'. Despite desperate attempts from strength elitists to brand bodybuilders as 'all show and no go", bodybuilders have been synonymous with excellence in strength sports. And that's without a lifetime of pure powerlifting specialization. Lou Ferrigno, Franco Columbu, Stan Efferding, Ronnie Coleman, Ben White, Johnnie Jackson and more have boasted strength performances that would make most lifting purists blush. In fact, one trend that stands out is how quickly women with physique or bodybuilding backgrounds excel in powerlifting and strongman, even outpacing former athletes. It turns out that tempering your body to high volumes of work with a wide variety of movements sets you up to become really strong, really fast. What's important isn't that some bodybuilders got strong bodybuilding, so we should all go bodybuild. It's that the methods they used to grow mass at the highest level have been used successfully in the programs of some of the strongest strength athletes in the world. We can look all over the record books and find lifters who used methods that might not pass the average competitor's standard of 'real powerlifting training'. • Eric Lilliebridge would dedicate entire training days every week to pure bodybuliding work. One day would feature heavier attempts with his competitive movements and the next would include 6-10 accessory exercises for 4-6 sets of up to 20 (!!) reps. • 3x World's Strongest Man Bill Kazmaier would use up to 5 working sets of 10 reps in multiple compound lifts to start off his training cycles. When asked how he approached his tricep accessory work to help with his bench, he outlined numerous high rep isolation exercises that would come after his heavy pressing. In his words, "I would make them scream". • Ed Coan, the dominant 220lb lifter of his day, was hardly known for his freakish size. He is widely regarded today as the best powerlifter ever and he built that legacy on a pattern of simple linear periodization. He began with a lot of sets of 10 reps, then moved to sets of 8, then 6 and so on. He described building his smaller accessory lifts as giving him "a suit of armor" that would reinforce his strength performance. • Eric Spoto, who briefly held the all-time bench record, stated in an interview, "Most of the early years of my training consisted of basic bodybuilding training". In the same interview, he outlined a program that put almost all of his bench variations between 8-12 reps. • Pat Casey, the first man to bench 600lbs (way back in 1967), built his power with repeating sets of 5s and 10s, almost always finishing each exercise with a back-off set of 20. • Jeremy Hoornstra boasted a 675lb bench at 266lbs body weight, putting him at the 10th highest bench in a meet and making him the second lightest guy out of the top 60 (!!) all-time. Having competed in bodybuilding before powerlifting, Jeremy developed a world-class bench following a body-part split and by utilizing machines and isolation exercises for double digit reps. • Marisa Inda began her lifting career as a bodybuilder before working towards the all-time 114lb record total. She still leans on bodybuilding methods like drop sets with her accessory work, stating that, " In bodybuilding, you hit everything. There are not weak links." • Suzan Salazar earned an IFBB pro card before starting her powerlifting domination, where she became the first woman to hit a 600+ wilks score in sleeves. • And then there's Doug Young, who inspired one of the auto-regulation methods used later on. Doug was a monster bencher, hoisting over 600lbs in contest at well under 300lbs body weight. His physique was just as impressive, as he possessed density and proportions that, while not seen as often today, were a hallmark of the 70s lifting era. His broad shoulders and narrow waist contrasted with an obvious aversion to manscaping to make him a modern day lifting meme. Anyone who has stumbled upon articles of Doug Young's training will certainly have noticed the immense amount of volume over numerous bodybuilding exercises that led to his legendary form. Now, obviously there are many successful recreational lifters and world champions who have used training methods that didn't lean on very high reps with bodybuilding accessory work to round out their physique and establish a wide base. For example, many world record holders came out of formal state-sponsored systems that used the same few lifts multiple times per week and progressed the workouts through subtle changes in weekly tonnage, intensity and total number of lifts. Not only does that monotony hit like Chinese water torture with a barbell but it's not likely to work as well unless you have the veteran coach with the clipboard observing you in person before working the calculations on your behalf. It certainly isn't appropriate for inexperienced lifters on their own. Other examples are the recreational lifters who had success with simple western programs, the kind that exploit the developmental power of compound lifts by only prescribing a few of them at a time and running them with a simple progression cycle. I'm a big fan of programs like Starting Strength, the Texas Method and 5/3/1; they work for just about everyone and only require a cocktail napkin to lay out the bones of the program. But these 'forever programs' that grind progress with the indefinite addition of 5 more pounds have limits, both physically and psychologically. I remember one coach, who used a 5s based linear progression with his clients to GRIND out new PRs for weeks on end, lamenting how one of his best guys stopped before a set one day and exclaimed, "you gotta give me a reason to keep doing this". I'm choosing to emphasize programs that prioritize mass because it solves some of these problems, especially for newer lifters. The workouts are varied enough to keep you from jumping off a building but similar enough to practice skill in the main movements. The effects of these protocols will also prevent weaknesses from developing and give you more practice for advanced programming down the road. So, we accept that there is a theoretical minimum amount of mass that you need to be competitive based on your frame. Then we must accept that the quicker we slap it on to your bones, the better. For those of you who haven't been influenced by Weider's principles for growth, Arnold's Bodybuilding Encyclopedia or a decade-long subscription to Flex and Muscular Development, let me summarize the things that grow muscle faster. COMPOUND MOVEMENTS Compound movements are any movement that involve work at more than one joint. They have long been known to give the most bang for the buck in regards to strength and size development. Give me just a barbell and plates and I can prescribe a spread of compound movements that will put mass over your entire body. Using multiple muscles to move a weight allows for more total load to be handled, which is a huge trigger for growth. There is also something about working a movement pattern over just stressing a muscle that adds something to the adaptive process. More complex movements require coordination, both with how muscles interact with each other and with the order in which individual motor units are recruited. As a lifter increases coordination, more reps can be performed with more weight, further increasing the stress the lifter experiences which creates new growth but also requires further coordination. This positive feedback loop leads to immense growth in a short period. Compound movements are great but that doesn't mean we have to commit to them at the expense of everything else. We will always use squatting, pressing and pulling as main developmental tools but we can still include a variety of other methods to compound how quickly we grow from each session. We can also use this pattern of 'growth driven by coordination' to our benefit when we plan our progression with new variations of the main movement from block to block. VARIETY OF EXERCISES Each muscle is made up of muscle fibers and those are bundled into 'motor units'. Each bundle averages around 150 fibers, which are all triggered to contract from the signal of a single motor neuron. Each specific movement requires a unique pattern of motor units to be triggered and an unfamiliar movement pattern will require use of a different pattern of these bundles. Casual gym lingo refers to this as 'hitting the muscle from a different angle'. Yes, bench pressing will grow your chest. But your chest will grow more if you bench press, incline press and dumbbell fly. With each variation, a broader assortment of motor units are stimulated to grow and the result is more mass and fewer weak points. VARIETY OF REP RANGES Instead of worrying about the difference between fast and slow twitch fibers (which can change with specialized training, anyways), I prefer to think about the nature of low and high threshold motor units. Smaller, low threshold motor units are the first to come on line and they become aided by larger and larger fibers as the demand for more force production is needed. This is where heavier work at lower rep ranges comes in; pushing the load higher over time conditions these high threshold motor units to grow. However, higher rep ranges are associated with greater overall hypertrophy. That may be due to reaching an optimal amount of work over an entire workout rather than the magic of a single set of 10, but there is no denying that getting into the weeds with double digit reps offers a growth benefit that heavy weight can't reproduce. As a longer set goes on, all of the high threshold motor units that were initially available fatigue and fall off-line. The nervous system attempts to keep the train going by recruiting nearby motor units that were previously dormant. Keep in mind, your body doesn't allow you to pull all of your motor units at once. That amount of sudden force would rip tendon from bone and exhaust all of your energy reserves, leaving you too fatigued and injured to even breathe. So part of the mission of strength training and bodybuilding is to trick your body into stimulating new motor units so that we can A.) get them to grow and B.) have them on-line and ready in the future. Strength-specific work with heavier weights will steadily increase the number of motor units used with each attempt but so will longer sets that involve high levels of fatigue. It is in our best interest to exploit both. INCREASING VOLUME More work = more growth, period. Volume is associated hypertrophy, so much so that 'volume' and 'hypertrophy' phases in programming lingo are often interchangeable. Volume is best thought of as the amount of work done in a session and that goes up when the number of sets and reps go up (even though load goes down). 10 sets of 15 is extremely high volume. Too much, perhaps. 3 sets of 2 is extremely low volume. Most lifters have a concept of 'progression' that centers around load; if stress is supposed to go up, that must mean adding weight, right? Very few have spent a substantial amount of time figuring out how to progress other variables, like volume. Any linear periodization program will start with high volume, something like 5x10, before immediately increasing weight and dropping the amount of work. The problem I have with this is that the highest volume workout happens when the lifter is least conditioned to it. It makes more sense to actively increase volume week to week, so that the biggest stress comes when the lifter can actually hit the gas without getting dizzy or throwing up. There are a few progressions I've used in the past with insane results that simply limit weight jumps in favor of increasing the number sets and/or reps and I've included those in the templates to be discussed later on. HIGH EFFORT/FATIGUE Many young lifters chip away for hours in the gym, using each set as a form of self harm, and manage grow week to week despite the absolute mess that is their training organization. The reason is that, in both high and low rep ranges, high effort is an extremely potent driver for growth. With low reps and heavy weights, increased effort puts more tension on the muscles and increases neurological action. Pushing as hard as you can through the lift (in the vein of compensatory acceleration) increases high threshold motor recruitment, digging out those pathways so they are more readily accessible in the future. This is compounded if you've got the adrenaline spike that comes from blasting "Kiss from a Rose" in your Beats and freebasing ammonia salts. High effort with low reps causes more damage to each muscle fiber as well and creates a high substrate deficit (lack of available fuel). Both are thought to be major triggers for growth. The lack of substrates (or buildup of waste products, if your glass is half full) that create the experience of fatigue seem to be independent drivers of muscle growth. Bodybuilders have, for years, found ways to increase the symptoms of fatigue during training. Some creative protocols were born out of the desire to increase the pump or to intensify the burn. even at the expense of variables like load that were thought to be more important. Blood-flow restriction training, which creates these symptoms by trapping blood instead of intense work, has actually shown to increase size and strength from low intensity efforts..... even from just walking! This suggests that reaching a high level of local muscular fatigue is an invaluable trigger for growth by itself. Now, I'm not saying you need to tie off your arms like an extra in the Wire to get results. I am saying we can exploit this by using advanced fatigue techniques with high rep work to build key muscles without compounding stress on the joints with ever-increasing weights. EAT AND REST Growth happens when you recover. For your body to do it's thing, you need plenty of raw materials and time away from the gym. I'm going to spare you the diet lecture, since the entire strength industry has had the same few talking points regarding diet on repeat for about 40 years now. Calorie surplus to grow. A gram of protein per pound of body weight. If you can do that, you won't have a problem. If you are very focused on body composition and want more insight, there are plenty of sources for that info who are more qualified than I am. As far as recovery goes, that's baked into the programs. The templates to come are all specifically arranged to include enough of a break in between monumental efforts so that you don't fry yourself and start backsliding. Just make sure that you aren't running ultra-marathons or participating in Vegas turnaround trips in your off days. SPECIALIZATION Every task that you try to get really, really good in is built off of numerous constituent parts that contribute to the success of said task. Consider the following subjects you might want to specialize in and the underlying qualities needed to do so. Public Speaking Control over your nerves in stressful situations, a wide vocabulary, strong communication skills, quick reaction time, sharp pacing Tattoo Artistry Steady hands, hand-eye coordination, focused and patient temperment, creativity, awareness of color, shadow and depth, large bank of visual media Waiting Tables Sharp memory, strong communication skills, short term planning, strong pacing, control over nerves in stressful situations, visual awareness, steady hands, focused and patient temperment Specificity is a method of specializing; it means focusing your efforts on doing the actual thing (or things close to it) to improve in that particular area. If you want to specialize in public speaking, just start speaking in public. Do it every chance you get; at parties, weddings, open-mic nights. You will be bad for a time, but you will steadily gain confidence, round out your approach and become a better speaker. Another way is to, instead, focus on the smaller pieces that make up the whole; these are activities that are still helpful but non-specific to the end goal. You can increase your vocabulary by using a 'word of the day' calendar and highlighting every word you don't know when you read to look up later. You can practice your communication skills by having more one-on-one conversations, by tutoring or by creating instructional presentations. You might practice your pacing by recording speeches you give in front of a mirror so you can experience where your speech moves too fast or gets too wordy. All of these non-specific activities are essential to getting better at public speaking and increasing them will surely set you up for success down the road. But none of them will replace the specific experience that comes from actually standing up and talking in front of a crowd. Both methods of attack are equally important, since each approach addresses some specific means of development that the other one lacks. That's essentially what periodization is in athletics and what the Base/Peak model tries to illustrate. We start out building a rigid foundation, getting better at each individual piece that is required for success that won't be improved by actually doing the thing. To bench a lot of weight, you need a fully developed upper body, including the triceps, lats and rear delts. Benching by itself is a great way to get better at benching but it will never optimize the development of your triceps, lats or rear delts by itself. To do that, other work is needed and that makes up part of the 'Base' that we are talking about. Specificity has to come after a wide enough base has been built. It doesn't do you any good to start speaking in public if you aren't comfortable with the language, not effective at communicating basic ideas and immediately start shaking and forgetting your lines as soon as you have eyes on you. It stands to reason that addressing those issues first will give you a much more substantial return when you finally do start getting on a stage in front of hundreds of people. This order of operations is 100% the same in all arenas of sports preparation, including strength sports. The Base/Peak pattern doesn't just apply to the 16 week cycles that take you through these phases on your way to competition day; it applies to the long-term journey from complete newbie to seasoned champion. The most specific methods of strength training, those that stay very close to what game day scenarios look like, are not warranted for those in their first year of development. We save super-specific training protocols for the most advanced and competitive performers. A frustrating problem with modern lifters is that they routinely skip the basebuilding work in favor of highly specialized training. There are a lot of reasons this happens but the big one is immediate gratification. The desire to be a champion NOW leads lifters who train solo to see their favorite world-record holders as role models and copy their routines. This is like giving the State of the Union with a 5th grade vocabulary. Where they should be paying dues by building a foundation of basic mobility, coordination, endurance, tendon strength and, of course, muscle mass, the unchecked newbie instead opts for methods that 'feel' like real powerlifting. I can't tell you how many conversations I've seen from first year lifters kicking around the idea of running Smolov or a Bulgarian split. For those who don't know, those are both approaches to weightlifting that weren't prescribed to an athlete until the coaches thought they were already good enough to be considered for the Olympics. This should put a big exclamation point on why volunteered Bullmastiff to be the tool for highlighting the journey from novice to advanced in Peak Strength. The flavor of training Bullmastiff provides (a wide variety of sets, reps and exercises) gives the fledgling lifter a huge head start in checking off these developmental bench marks while giving them the experience with different movement variations and programming transitions that will need to be implemented when they become more advanced. Let's evaluate the specific qualities that separate new lifters from advanced ones to determine how specialized their training should be. NOVICE LIFTERS • Inefficient in the barbell movements; lacking in coordination, timing and consistency • Lacking in muscle mass • Low work capacity • Psychological approach is inconsistent; apprehension with big lifts, cues ignored during harder efforts • Low bone density and connective tissue strength • Low local recovery, high systemic recovery The biggest curse of the novice lifter is how fast they grow from absolutely everything. You might intuit that it's a good thing that any exercise for any amount of work provides near-immediate strength gains and that those gains provide some benefit to just about every other activity. It's not. As cool as it is at the time, newbie gains insulate lifters from dealing with consequences from their bad training decisions. Where one should be cutting their teeth on sound training principles by figuring out how to balance stress and recovery and avoid diminished returns, novices instead bounce gleefully from workout to workout, like a gonzo film without a plot, void of any thought or care of the brick wall that they will soon run into. The reason that novices grow so well is because modern humans are artificially weak and undeveloped from our mostly sedentary lifestyles. The baseline for homeostasis for the human body is actually closer to that of a construction worker, middle-distance runner or anyone, really, who has some regular lowintensity work in their weekly routine. Just like shedding 100lbs is relatively easy if you started at 900lbs, gaining muscle and strength is relatively easy when you start lower than where your body naturally wants to be. Some programs address novices by trading a lot of fitness fluff for simple homework. Starting Strength (which I'm actually a big fan of for multiple reasons) emphasizes practice with the same few lifts on a basic linear progression that even a chimp could follow. You only need to squat 3 days per week because, as a novice, you can do that and grow. You add 5lbs every single time because, as a novice, you can do that and grow. You only focus on the bar bones because new lifters are prone to 'shiny object syndrome' and focusing their efforts on just a few important variables will increase compliance. It works beautifully and it's what I recommend when I need to explain to a nonlifter what they should do when I only have 3 minutes and a cocktail napkin to explain it. The only blind spot I see (all programs have one) is that it prevents practice with the fundamentals of programming. Novices can get away with a 3 day per week program driven by daily weight jumps, but they don't have to do it that way. They can do anything and grow. I would prefer to see an approach that gets the novice comfortable with working their training through some pre-planned cycles while experimenting with movement variations that will suit them down the road. I see that experience as just an important part of Base development as any amount of physical strength or endurance. The trade off is that a little more attention has to be paid to what's going on. That means we will lose those people who need to keep it to the level of the cocktail napkin. Those who can stretch their attention span, however, will be exponentially better for it. INTERMEDIATE LIFTERS • Comfort and consistency with the barbell movements; technique is more efficient but may still need refinement and consistency • Greater muscle mass than average; more mass needed to advance and physique might be showing lagging muscle groups • Work capacity is sufficient to get through hard workouts • Improved psychology; approach to the barbell is becoming ritualistic but there still may be breaks with high-stakes attempts • Bone density and connective tissue strength has started to increase • High local recovery, medium systemic recovery Intermediate is a tricky term to pin down. It represents a very broad island in the middle of your journey and an alarm doesn't exactly go off when you are arriving or leaving. This list outlines what it is supposed to look like but people have a funny way of not fitting in the lines. There are all kinds of guidelines one can find to try and place your level of advancement, ranging from years of experience to strength/body weight ratios and none of them tell the whole story. A cheap guideline is to take the world record of a given lift at your weight and gender and look at the range between 50 and 70%. The best conventional deadlift from a 220lb male is just shy of 900lbs (I believe it's Tom Martin with a conventional 887lbs). The intermediate range is roughly 440lbs to 625lbs. That's a big spread, I know. A 440lb pull around 220lbs body weight represents a point where you are beginning to get something that looks like strength. This isn't winning contests any time soon but it is more strength than a similarly sized guy will have without some specific training under his belt or, at least, a job that involves regular physical labor. The big point is that the emergence of above-normal strength represents a change in how you need to pace your training efforts and which type of activities will or won't increase your deadlift further. That is the entire purpose of separating lifters into these groups in the first place. A 625lb deadlift at 220lbs is closing in on competitive levels of strength and should be where you look for signs of a changing recovery dynamic. If you are following the same split as when you were pulling 500 with the same frequency of hard efforts and you are finding it harder and harder to meet the demands of each workout, it might be time to incorporate some more advanced methodologies. It is really important that you incorporate how skilled and advantaged you are into your analysis. Very advantaged lifters (long-armed deadlifters, for instance) might blow through these numbers without the need to make many changes to their training; they might benefit from novice tactics longer and be much more competitive down the road before implementing advanced methods. My short arms and longer torso give me a huge disadvantage in the deadlift, so much so that I had to incorporate some advanced-level trickery long before my numbers came close to competitive. This shows beautifully why world record holders often make poor role models; they represent the most advantaged humans among us and the strategies they discover and use are often tailored to those advantages. Your primary goal as an intermediate is to get a rock-solid handle on your recovery timeline for each lift so that training can be sustainable. I call this 'finding a cruising altitude'. It will take some trial and error but eventually you have to have a sense of how many sessions per week you can handle, which thresholds take longer to recovery from and what lifts or activities interfere with that recovery. You might notice that challenging overhead sessions require 4 or more days of rest before you can bench press effectively. You might notice that heavy deadlifts require more than 7 days rest before you can reproduce that effort. Or you might notice that you can handle just about anything as long as you keep the RPE in a tight margin. It's subtly different for everyone and no one can figure it out for you, so start paying attention now. Your secondary goal is to start using main movement variations more surgically. Novices should use plenty of different movements the way youth athletes should play a lot of sports: everything makes them better at everything and the familiarity with extra movements will be useful later on. As an intermediate, you will finally be strong enough to see weak points emerge by contrast. Make a few educated guesses as to which muscles or parts of the main lift are lacking, practice targeted variations/accessories long enough to improve at them and measure if there was improvement on your main lift. If becoming advanced at any point is on your bucket list, trial and error along with rigorous note taking is the only path there. This is only for people who are here for the long haul. ADVANCED LIFTERS • • • • Extremely efficient and consistent with each movement Optimized amount of muscle mass and extremely well rounded physique Work capacity remains high Psychology is absolutely dialed in; machine like approach to lifts, cues are automatic • Bones are dense and movements are supported by thick tendons and ligaments • High local recovery, low systemic recovery Advanced lifters will represent the most specialized group in their field. Their technique will be razor sharp, having been tweaked over the years to suit their build and remove any inefficiencies. Some advanced lifters have what might be considered a 'non-optimal' technique but years of training have forced their bodies to adapt around it so that they are still able to perform at the highest level. Technique work is constantly reinforced by the most sport-specific movements; this isn't because they are trying to get their already-elite technique even better but rather because future success hinges on retaining the skill they've developed so far. They simply can't afford to lose a step when it comes to skill so a greater ratio of work is done with contest specificity. The high level of skill advanced lifters possess gives more bang for the buck when it comes to creating a growth stress. Because the body has adapted to milk each structure for greater and greater performances, each hard effort represents a monster stress to the entire system. Sure, years of training will make each muscle near-impervious to muscle soreness and fatigue from general training but systemic recovery from a hard effort takes much, much longer. Given these circumstances, many tactics that worked in the beginning are counter-productive now. You can't max every session with the same lift and get a good result. The same goes for amrap sets, repeating work at high percentages and very high volume/high effort workouts. For any of these tactics to be sustainable with an advanced lifter, they have to be placed further and further apart from each other with the other workouts being made up of different movements, different thresholds or reduced efforts. THE BASE/PEAK MODEL We talked about labeling lifters as novice, intermediate or advanced based on how specialized they need their training to be; novices need variety, elites need specificity. Bottom to top, training should go from broad to narrow. The same pattern is used to optimize training in the short term and is especially important for preparation over a competitive year. This is represented by the Base/Peak model, which is just a conceptual method that simplifies what periodization has been doing for decades. These are the nuts and bolts of training because they give insight into what you should be doing NOW and how you need to change it around the time that stops working. BASE QUALITIES FOR STRENGTH MASS I started this book with a long rant about the importance of muscle mass, so I'll spare you from having to relive that. I'll just give some context as to how that training should go. Most of the mass-specific training you do should come at the start of a training cycle, furthest away from any upcoming contest or testing date. This is universal in block and linear periodization, to the point that early phases are labeled as 'hypertrophy' phases just as often as they are labeled 'volume', 'accumulation' or anything else. Muscle growth is at it's highest when volume reaches a certain sweet spot. On the spectrum of volume, long efforts at lower intensities, like cycling for instance, can absolutely lead to growth of the leg muscles, just like a few years of maximal squatting might as well. But in the short term, muscle growth won't be optimized if the weight is too light or if the reps are too low. They need to balance. There's a reason that a 10 rep set is the golden standard for bodybuilding work and it isn't because 10 is a nice round number. Studies show what most gym rats and self-taught lifters already now, that work around 10 reps, or 45 seconds of work, provide superior short term growth than ranges significantly above or below. It's because sets of 10 correspond to the 70% range, the point where the amount of weight on the bar balances with the amount of work that can be done. So, developmental work in the beginning phases of a periodization scheme will hover around that point, maybe staying between 65-75% for the 4-6 weeks that period needs to last. Some programs will use sets of 10 or so and build up a lot of fatigue in each set while others might keep the reps lower to prioritize crisp technical practice and use a greater number of sets to build volume. The important takeaway is that a lot of total reps with the main movements around this percentage range will lead to rapid short term growth and that is doubly so if this range represents a stimulus you aren't familiar with. The other side of the 'mass' coin is focused accessory and isolation work. Where hypertrophy work with the main movement represents a hammer, these smaller 'helper' movements are more surgical. Remember that the main lifts are fantastic developers but, by themselves, leave holes that can turn into weak points down the road. If we want to set ourselves up for a brutal run of PRs at the end of our training cycle, we need to come into the later strength phases more efficient and well-rounded than before. That means picking movements that will spark growth in lagging triceps, tiny delts, invisible lats and flat glutes. If you really want performance to close in on 'elite' territory, you will even have to dedicate training to hidden areas like bracing ability or rotator cuff strength. None of that is going to happen with just a barbell. Machines, dumbbells, cables, body weight exercises.... there is a huge selection of potential exercises to solve any given problem. The beauty is that we don't have to be as careful with these exercises the way we have to with the big movements. Pushing the limit on dumbbell rows and delt raises will lead to a lot of local fatigue and soreness but the fatigue doesn't register systemically. The body can roll into the next workout without really being any worse for wear. By taking these smaller movements to and beyond failure (with advanced fatigue techniques that will be explained later on), we can trigger growth from two sides, the side of weekly volume and the side of immediate fatigue. The synergistic effect results in more growth in a shorter period of time. SYMMETRY If you are in the heaviest phase of your program, say, 6 weeks out from a meet, and you notice that your hamstrings are underdeveloped relative to your quads and glutes, it's already too late. The weight will be getting heavier each week and total volume has to drop to allow recovery, so smaller exercises have to go on the back burner. That makes it so important that symmetry is emphasized early on in the Base phase. For your pressing, evaluate how big the main movers are to each other (shoulders, pecs, triceps) and then compare how developed all of those are to the antagonists (lats, rear delts, biceps) and stabilizers (muscles of the rotator cuff). All of those muscles have to grow over time and, when water is scarce, only the important things get washed. For squatting and deadlifting, see if there are obvious differences between development of the glutes, hamstrings, quads, abdominals and erectors. Then look where you are weakest in each lift. Does your back round more with heavier deadlift attempts? If so, focus on developing your erectors, abdominals and bracing ability. Are you slow at lockout? Then the glutes need more work. Do you tip forward on heavy squats? Increase the amount of quad work you do. You simply can't justify chasing big weights in a Peak phase until you bring these areas into balance. COORDINATION You never want to go into a contest uncertain of your technical approach. By the time the percentages start getting into unfamiliar territory and you see PRs on the horizon, you should already be moving like a well-oiled machine. There should be no thought, no hesitation, no last minute changes. Blindfolded and on Ambien, your squatting, pressing and pulling should look crisp and effortless. Coordination with the big lifts begins with sub-maximal weights. Every technical change you make can feel awkward at first, even if the change represents a more efficient position, so the loads have to be light enough that you can force that cue without the rest of the lift falling apart. Once you apply that change, you have to drill it over thousands of reps until your body changes to accommodate it and you instinctively recognize it as an effective setup. Start with the universal cues that make you tight, stable and consistent. Once those are second nature, go through the process of tweaking minor details to your preferred setup. Deadlifts, squats and presses will all challenge individual lifters differently and it is up to you to work your technique around your specific needs. CAPACITY To shine in any phase of training, you need to be able to handle a certain amount of work without fatigue setting you back. An effective Base phase will do this by slowly tempering you to more and more work over time. Running through higher volume workouts with reduced weight is a good start, especially when those reduced percentages get you into double-digit reps. But you can take that one step further by specifically including work for it's conditioning benefits. Some of the options: • Smaller accessory work can be done every-minute-on-the-minute or in circuits. In addition to improving general conditioning, this can help growth by increasing the density of the work. It's an effective, if little talked about, means of increasing stress and benefits from the fact that accessories can be worked harder without sidelining the whole program. • GPP workouts can be included on off days or at different times of training days. General physical preparedness workouts involve a host of less taxing work to help with recovery and jack capacity up. While things like sled pushes and plyometrics are non-strength specific, the conditioning they offer will allow you to tear through much more difficult strength training workouts without gassing out. • Strongman work can be used during workouts or on separate event days. The success strongman competitors have with the deadlift is largely a byproduct of the type of event work that has to be done year round. Where typical deadlift working sets might last 10 seconds or less, carry events might involve 30 seconds to a minute of continuous movement with supermaximal loads. Hypertrophy in the posterior chain is an inevitability, as is elevated levels of work capacity. PSYCHOLOGY Lifting maximal loads requires both precision and aggression to be high and, as sports psychology teaches us, there is an obvious inverse relationship between the two. Think of your mental state when aiming to hit a bullseye on a dart board or trying to bowl a strike. Now think of it your state if you were to throw either implement as hard as possible. High arousal means low precision and vice versa. Where your fall on the chart of precision and aggression will depend on a whole host of individual factors and you need every rep of your Base phase to figure that out. Some lifters walk into the gym as absolute monsters, using screams, slaps and smelling salts to summon the greatest amount of neurological output. These are the guys who have a mountain of pink ammonia caps piled up before their first working set. If that works for you, great, but me mindful that getting over-hyped can be just as devastating to a maximal attempt as going in cold. If you are prone to rushing commands, getting out of position or blowing your energy reserves for any later attempts, over-the-top theatrics might cost you more than they give back. Some more calculated lifters benefit from a Terminator-like presence. I'm reminded of Zydrunas Zavickas, who established himself as the best strongman of all-time who set world records while never showing so much as an eye-twitch. Practicing stoicism while training will make your lifts deadly and predictable and will insulate you from having swings of emotion determine how well you perform. It also will make insanely sensitive to contest adrenaline when the right contest circumstances hit. There's nothing like watching the introvert glow red with quiet rage when he smells the blood of his opponent. Whatever approach you take, remember that it's peak performance you're after and not the attention of strangers. JOINTS AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE Joint health is the most important part of the equation for elite hopefuls and the one least talked about. How much weight you can handle, either in a meet or in training, is dependent on how strong your structural foundation is. Muscles grow pretty easily, so much so that they can easily outpace the tendons that anchor them to bone. Those tendons lack a sufficient supply of blood flow, so they grow much slower and take exponentially longer to heal when injured. Anyone who has suffered both will tell you that a broken bone is often a better option than a severely sprained tendon. Base phases provide a break to your joints and connective tissues from the beat-down of heavy loads. While you are working for increased muscle mass from all of those reps at reduced percentages, your tendons and ligaments are also getting the chance to thicken. We have a few competitive arm wrestlers in our area. The wisdom from the best guys, who often suffer severe joint and nerve pain from the constant pulling and torquing, is that the hardest table work should be immediately followed by more work. When they are so beaten from long practices that they can't sign their name, they will often go to the gym and do a myriad of lighter resistance exercises, usually with bands and for high reps, so as to force blood into the tendons and accelerate the recovery process. As you work to widen your base as a lifter, remember the role that these methods have in preparing your joints and connective tissue for maximal efforts. Big movements provide the load, which will lead to tendon growth. Smaller movements move around blood and deliver nutrients for growth and can also be powerful tools for combating inflammation and overuse issues. SPECIFICITY/RECOVERY/NOVELTY A Base phase of training can last 4-8 weeks for someone on a tight block periodization-type contest prep or months for an intermediate looking to sufficiently bulk up before chasing heavy weight again. When it's time to focus on specialization by switching to a Peak phase, it's important to recognize what exactly is happening with that switch. In short, the stagnation that occurs from doing the same thing repeatedly gets disrupted when you change specificity and recovery while including novelty. • The Base phase represents low specificity. When specificity is increased in a Peak phase, whatever improvement we got in Base qualities are put to work and exploited to break through new barriers. As we make strengthspecific adaptations in that context, numbers go up even more. • Fatigue is high during the Base phase (because volume = growth) and we know that fatigue hides strength. If you are recovered enough to display top end strength, it means you haven't really been working hard enough to grow. When the weights get heavy, increasing recovery by dropping the amount of work we do leads to an upswing in growth. That growth means heavier weights and that means a greater training effect. • Novelty is the big one. The simple fact that we are making changes will cause us to start responding to training again, regardless of how focused they are to the end goal. Novices and intermediates can really milk this, but more specialized lifters will need to stick to a tighter list of novel stimuli if they want it to carry over to their specific goal. TRANSITION TO PEAK: STRENGTH-SPECIFICTY LESS MOVEMENT VARIATION More work in a Peak phase has to be made up of exercises specific to the main movements. Frequency might increase, moving from once to twice per week, and lighter variations might be replaced with ones that are heavier and look more like the main lift. Part of optimizing strength performance is dialing in technique and staying in position under heavier loads. The more touches we get greasing that groove, the better off we will be. Generally, smaller accessory exercises go by the wayside so as not to pull from the limited well of recovery. 6 weeks out from a meet, bicep curls and chest flys won't do a thing to help your performance. But they can set you back by stretching you thin. LESS LOAD VARIATION Double digit reps won't help us here. The pacing of the workouts have to get us comfortable with performing under loads that challenge our ability to put out force. The Peak phase might start out with sets of 5 and 6 but 3 reps and less are where the most contest-specific practice happens. Most of the work will be int the 85-95% range and higher-rep variations and accessories will be replaced by targeted variations that work in a similar threshold. Part of the move to specificity will be to select movements that allow the heaviest loads to be handled. Partial movements allow for an intense stimulation of the nervous system by exploiting mechanical advantages near lockout. Even without substantial ranges of motion, experiencing these loads creates a change in how aggressively the nervous system recruits motor units. Static holds, eccentric overloads, board presses, rack pulls, etc can all be effective tools at optimizing strength development in a Peak phase. MORE WORK ON WEAK AREAS Variations will still be a staple but they have to be limited to work that will cause short term growth. That means reinforcing the last few weak spots that could hinder performance in a maximal attempt. Where we were prioritizing balancing out our physique with a broad array of movements early on, now we need to evaluate where technique breaks down and spend more time in those positions. Elevated lifts can increase strength at that specific height and deficits and pauses can increase starting power. There is a thorough list of movement specific variations later on, complete with full explanations of which weak points they address. SQUATS, PRESSES & PULLS Lifting culture is at the point where anyone who has been at this for a day recognizes the importance of compound barbell movements as effective strength and mass builders. It's not even a question. Another big reason to prioritize them ahead of, say, machine work is that they are represented in competitive arenas. If you get big and strong from squatting, pressing and pulling you will already be set up to transition to powerlifting or strongman, which requires specialization in squatting, pressing and pulling. The technical nuances of these lifts is way beyond the scope of this book and I'm not going to patronize you by filling up paper with a bunch of vague cues. Everyone's different and it will take some time to dial these movements in exactly to your needs. Just get technique passable so you don't end up with herniated discs or unnecessary overuse issues. SQUAT Squatting should be the backbone of any strength program because it checks so many damn boxes (we are all about checking boxes, if you haven't caught on). It is inarguably one of the best size and strength developers for the lower body, so much so that some of the biggest displays of both size and strength have been built off of programs with little else but squatting. It's more specialized towards athletics, since the movement of the ankle, knee and hip is similar to what many athletes experience in the field of play. As great as deadlifts are at building strength, nothing on the track or in the field looks like a deadlift. It's also one of the easiest movements to recover from systemically, meaning it can be trained harder more often without compromising recovery for the rest of the week. It builds strong knees, encourages mobility through the hips and ankles and, as verified by anyone who has ran through German Volumizing or Super Squats, will actively build pain tolerance, resolve and basic character. FOR NOVICES If you are new to squats, 'passable technique' means reinforcing good habits that will set you up for success while eliminating bad ones that will get you injured quicker. Good habits include getting the hip crease below the knee (every time, not just when the weight is comfortable), maintaining posture and a strong brace throughout the entire lift, keeping the knees from falling in on the way up and making sure that your heels are glued to the floor and not twisting in or popping off the ground. Bad habits include violating any of those things. Once that happens, the set is over and the weight has to come down. I bias towards getting novice lifters comfortable with a more upright, narrow stance squat regardless of build. I feel that it has more technical carryover than wide stance squats to other activities, like Olympic lifting, track events and most strongman events. Developmentally, the upright position and increased emphasis on the quads makes it a better antagonist to deadlifts, which start bent over and put a heap of stress on the entire backside. That being said, the benefit of upright (or high bar) squats won't make up for what you lose by keeping the load light because the movement is horribly awkward for your build. Those with long femurs and short torsos might find that a wider stance and more bent over position is the only way that any meaningful work can be done. That's fine, just make it work. BEYOND NOVICE As you advance, there will be subtle things you tweak to get a competitive advantage. You might play with your stance, change the bar height, practice building more tension in the hole by pushing your knees out or bracing differently. These are all well and good, but remember that you get good at how you train. The marginal benefits of each technical change won't make up for the cost of lost ground that comes with reinventing your squat every 6 weeks. Find what works and feels good and then drill it until you can do it in your sleep. DEADLIFT As a strongman competitor, squats make me feel like I'm cheating on deadlifts. As I said, they are an antagonist to squatting but are every bit as important in the development of useful strength. Most of real life strength involves bending over and picking things up and even if the movement is not completely specific to your sport, the hip power developed from deads transfers to just about everything. The bent over position disadvantages the upper back and midsection as much as anything you can imagine which forces the acquisition of a lot of strength and mass in those areas to compensate. The reason they are so good is also the reason that they are so bad: the high stress they place on so many large muscles. For developmental purposes, it's fantastic but for recovery, it creates potential pitfalls. FOR NOVICES Novice lifters fall in love with deads pretty quickly because hard efforts yield big returns out of the gate. Novices aren't typically strong enough to illicit a big systemic stress from all-out efforts, so they can push the envelope every session and still recover. Once they they approach that Valley of Intermediacy, the new found strength taxes the system to a much greater degree. Recovery chronically falls short and, as frustrated lifters try to bully their way through stagnation, injuries become more likely. I highly encourage new lifters to take the time to build tolerance to deadlift volume so that it doesn't eat them up when the weights get heavy down the road. This is best done by building a strong upper back and midsection, learning how to brace properly, practicing a smooth and efficient deadlift stroke and by slowly, steadily, incrementally adapting to higher reps and multiple sets. Any lifter who does this early on in their career will be able to chew through future deadlift training cycles unphased. BEYOND NOVICE Advanced lifters often struggle to progress deadlifts, especially while balancing the weekly toll taken by other big lifts. The workaround is usually to push hard efforts further and further apart, sometimes to every other or every third week. The trick is to prevent detraining and maintain familiarity with all of this time in between efforts. One method is to swap deads out for close variations, since subtle changes in neurological stimulus serves as a form of recovery. Another is to substantially dial back efforts using speed work or recovery sets to recover while keeping the movement fresh. Because deads are such a recovery suck, you HAVE to know where your break is. The templates later on take care of deadlift recovery in the Base phases (when volume and hypertrophy is the goal) by keeping the work sub-maximal and incorporating frequent resets in volume. When the loads get heavier and require more effort in the Peak phase, effort is controlled tightly so that the hardest efforts come only once ever few weeks. The technical aspect of recovery is just as important. A lot of lifters manage to get pretty strong despite sloppy pulling mechanics. I can tell you as a matter of pure fact, whatever effect getting stronger has on reducing your ability to recover from deads, it is doubled if you are bullying your way through hard sets with inefficient technique. As an advanced lifter, you need to know exactly where your start position is, how much your shoulders should hang, how much stiffness should be in your back and midsection and how aggressive you should be at each inch of the movement. If there is a question mark at any of these points, you have work to do. BENCH PRESS I'm going to be dead honest here: I hate benching. It's not that I'm not good at it; the short limbs that predisposed me to being a good overhead presser provided just as much benefit to benching. My bench career culminated with a 475lb dead press from pins off the chest, right around the time I was considering scratching a competition 500 bench at 220 off my bucket list. That moment never came and I'm not sorry for it. After that very cycle, I had severe bicep tendonitis near my shoulder that made any eccentric loading impossible. I've had rotator cuff and labrum tears that have kept me from any pressing for months on end. Even when I contorted myself into a shouldersback, high arched, top-of-the-belly bench press setup, I couldn't keep my shoulders happy during a cycle. I'm not writing this to scare any powerlifting hopefuls off of bench pressing. I just want to make you all aware that long-term benching has been synonymous with injuries and overuse issues in the general population; much more so than the other lifts. If you are going to plan out any kind of path to the top, you need to know what the common pitfalls are so you can avoid them. If you don't have to bench press in competition, you would not be mistaken for swapping full range benching for floor, board and pin presses as lockout accessory for your overhead press. That's what I resolved to do and my shoulders are happier than they've ever been, my overhead is soaring and I seem to have preserved most of my bench ability from keeping my delts and triceps strong. Competitive strongmen know what others have been guessing at for years; big overhead presses create big benches, but not the other way around. Now, if you do want to develop a competitive bench or are tied to it simply because it is such a staple in popular lifting culture (which I imagine most of you are), just be cautious. FOR NOVICES Novices get the most reckless because they haven't developed the chronic pain and scar tissue that comes with chasing big bench numbers for years at a time. This is a key marker on that road-map from the future I talked about earlier. CONTROL YOUR DAMN BENCH PRESS! Do not flare your elbows out to the side. Do not bounce it off of your sternum because it moves faster that way. And for the love of God, stop with the endless grindy attempts at the same 2.5lb PR. One of the better effects of powerlifting coming into popularity is that most trainees are mimicking competitive setups instead of just plopping down onto the bench, soft and ineffective like a gaffed fish. That brings us to another point which is that the powerlifting bench setup, while great for optimizing big lifts and keeping your shoulders alive to fight another day, is a really crappy developmental exercise. These templates come to the rescue in a big way here since the secret to a big bench is to prioritize a lot of non-benching activities. You need front and rear delts, triceps and pecs and those can be better targeted by borrowing from the well of proven bodybuilding exercises. You also need a big back and strong biceps and all the benching in the world won't get them for you. We are going to get the best of both worlds here by using just enough benching to build comfort and control while using most of our energy to build a really well-rounded upper body, free of weak points and inefficiencies. BEYOND NOVICE As lifters advance, they will be more prone to inflammation, pain, stiffness and inexplicable 'clicking' every time they lay down to warm up with the bar. Assuming you've sufficiently 'greased the groove' at this point and have an efficient and reliable bench setup, it's important to keep everything moving well by preventing weak areas from forming. There should be ample work given to keeping the rotator cuff strong and banded movements to keep the shoulder joint warm and mobile. Muscle imbalances between the front and back need to be addressed and eliminated. The movement variety that novices select for pressing assistance will largely be randomized so as to increase experience and build a wide base. More advanced lifters will need more specialization towards bench specific skill, meaning that each bit of variety has to solve a specific problem. We aren't just trying to build muscle for the sake of it anymore, we need to know what the weak link is in a missed attempt and reinforce that with carefully chosen specialty exercises. OVERHEAD PRESS On the other hand, I love me some overhead pressing. Aside from being a strongman staple and a much cooler demonstration of upper body strength, the overhead press led to some of the most dramatic changes in my physique and allowed me to keep my benching ability high without having to further torture my shoulders. FOR NOVICES 'OHP' is kind of a broad catch all, but most of you should just be doing a standing strict press. The world won't end if you do a seated press instead, but I will judge you for it. The spirit of an overhead press is exemplified when you stand on your own two feet and push an object as far away from the earth as your corporeal being will allow. It's a spiritual event, so don't spit on it by making it cozier for you unless you have a really legitimate reason. I personally prefer a push press instead of a standing strict press because it is my contested lift but it's a bit more technical and inconsistent at the start. I don't recommend it unless you are going to be competing in a strongman meet sometime soon. Get a minimum amount of strict pressing ability and coordination first and you will find that implementing leg drive on big lifts is a much more efficient use of time. BEYOND NOVICE Similar rules go for overhead work as benching. Mind your shoulders by keeping your mobility good and rotator cuffs strong. Warm up sufficiently, work to build a well rounded upper body and avoid ugly, grinded attempts. If you can do this, you should be able to keep progress ticking up for years to come. The result will be impressive shoulder caps and unrivaled pressing ability. If you are incorporating a push press or push jerk for strongman (or for fun) work to maintain enough mobility to rack the bar across your collarbone. As cool as it is to be so bound that 315 floats off your chest at the start of a press, that will severely hamstring your performance. Having the bar trampolining off of your elbows as you dip and drive is damn inefficient along with being a good way to strain your bicep tendon at either insertion point. VARIATIONS AND ACCESSORY WORK An effective strength program can be thought of like a really good margarita; if the main movements are the tequila, the variations are the mix. Sure, tequila by itself can get the job done but a bit of flavor will heighten the experience. Here are the benefits of incorporating variations of the main movements: • EFFECTIVE BUILDERS They create growth through the exact same pathways as the main movements, meaning that they should be similarly effective at creating new growth as the main movements. • NOVEL STIMULUS They provide novelty for the sake of it. When you incorporate a movement that features an unfamiliar pattern of loading, the body adapts to it quickly over the first few sessions. It's kind of like experiencing newbie gains all over again and is a powerful tool against diminished returns • TOOL AGAINST OVER-TRAINING The differences in loading result in a sort of recovery effect relative to the main lift. Since the neurological action is slightly different between main movements and their variations, the burnout that comes with training the same movement hard and heavy for weeks on end is blunted. This is useful if you want to train the same movement multiple times per week or transition from one block to another without deloading or resetting. • CAN SOLVE SPECIFIC PROBLEMS They can be chosen specifically to better fit the goals of one phase of training or to address a particular weak point for an individual To expand on the last point, Base phases or any period of training dedicated to hypertrophy are best suited by using methods that increase the total amount of work. The most common way is to focus on sets and reps but movement selection can do this as well. Compound movements that keep the stress similar while increasing range of motion (deficit work/disadvantaged movements) or forcing more time under tension (tempo/pause work) can augment the effect of a hypertrophy driven training period. In contrast, Peak phases or any period focused specifically on load tolerance or power output would benefit from variations that expose the lifter to more weight (partial/advantaged movements). As the lifter becomes more comfortable with the increased loads that are present during top end work, performance with the full range lifts also increases. Weak areas can also be fixed by surgically using variations of the main movement. Stick points at lockout can be addressed with top end work. Rough patches mid-lift can be addressed with tempo or pause work. Slow and inconsistent starts can be aided by incorporating a deficit. MORE SPECIALIZATION REQUIRES MORE SIMILAR VARIATIONS In youth sports, many coaches encourage kids to play multiple sports to keep them engaged and build skill and familiarity with a wide array of movements. Everyone knows the manic sports-parents who think they can produce the next Tiger Woods by getting their 5 year old to swing a golf club 30 hours a week. It turns out that this is actually the worst approach; aside from they psychological issues that arise, it robs the child of the ability to develop vital skills during the most formative years. These are the skills that are important for success that the main specific task doesn't improve (remember my rant on new lifters overspecializing too soon?). Lifting is no different. Novices up to early-intermediates do not need excessive specialization with their movement variations and actually benefit from including more variety early on. Note that the term 'weak points' implies that other areas are strong by comparison. New lifters do not have weak points; everything is weak and you fix that by casting a wide net in your training. Don't over-complicate things by trying to be surgical with your movement selection. Drill the main lift, use variations that encourage diverse physical adaptations and rely on the progression of sets and reps to drive growth. Only once your lifts are close to competitive should you start sniffing out potential lagging areas. More advanced lifters, on the other hand, don't have the luxury of losing the skill and specialization they've acquired over the years. Variation is still important for all the reasons listed before but you won't get carry over from movements that are too radically different. Advanced athletes are best suited when their lifting variations are A.) similar to the main movement and B.) targeted to fixing a specific lagging area. Keep in mind that this pattern of 'broad and varied versus narrow and specialized' is important in the short term as well. Over a competitive year, sports teams start their training cycle with a lot of variation and non-specific movements. Those movements become less frequent as game day approaches, having been replaced with things that look like what will happen during an actual game. We can say that more elite athletes need more overall specialization than someone in youth sports, but a high-school or college athlete will still periodize in a way that moves from broad to sport specific training movements as they get closer to the season. TYPES OF VARIATIONS Focusing variations towards a specific weak area requires knowing how they are different. The idea is that being disadvantaged in a particular way requires more adaptation at that point, reinforcing the main lift there as well. These are the common themes when tweaking the loading parameters for one of the Big 4. • MOVE THE FEET OR HANDS A narrow position puts more emphasis on elbows/knees, which force adaptation with their extensors, the quads and triceps. Wider setups put the stress at the shoulder/hip, similarly stressing the glutes and delts/pecs. • MOVE THE LOAD You can change where the center of mass of the movement is by placing the bar in a different spot or using a specialty bar. A side handle deadlift is much different from a straight bar, just like a front squat is different from a typical back squat. There are a lot of different ways to do this and they will all have their own specific carry over to individual muscles or parts of the main lift. • PAUSE OR USE A TEMPO Pausing can be done at the bottom of a lift or at some mid-way point. Doing so eliminates stretch reflex and bar momentum, creating a unique demand on the nervous system at that particular point. Moving at a tempo is also a deadly way of making lighter weight more difficult and increasing mechanical tension at points of the main lift where you can typically coast. • CHANGE THE ROM Shorter ranges of motion are synonymous with overload, since humans are mechanically more advantaged closer to lockout. Getting comfortable with top end movements can fix lagging lockout ability in addition to conditioning lifters to a greater neurological stress with the heavier weights that can be used. Longer ranges of motion, like deficit work, can increase power production around the deficit while also encouraging new hypertrophy. • INCREASE LOAD AT LOCKOUT Accommodating resistance involves the use of bands or chains to overload the top. Remember, we get mechanically more advantaged closer to lockout so the load changes over the lift to 'accommodate' the fact that we are stronger at that point. This can provide a gnarly effect on the nervous system by acclimating the lifter to extreme loads at the very top of the lift. It's also a good tool for teaching compensatory acceleration, which basically means hitting the gas throughout the entire lift. • INCREASE OR DECREASE STABILITY Using lighter weights with unstable movements can sometimes reinforce technique, increase control and take pressure away from dodgy joints. Think about using a Tsunami bar or benching with your feet off the ground. Too much instability will eliminate carry over to the main lift; keep this in mind before you jump on a swiss ball for your next set of squats. Increasing stability will shift the focus to overload by allowing you to move more efficiently. A stiff squat bar is more stable than a whippy Oly bar and will allow you to push greater loads as a result. • USE SPECIALTY BARS All specialty bars do something different, so do some research before blindly throwing them in. Trap bars and safety bars change where the load is. Cambered squat bars and Tsunami bars destabilize you. The Swiss bar changes your hand position. If you can connect a need for a certain adaptation with the intended use of a specialty bar, you're in business. If you walk in and play 'eenie-meenie-miny-moe' at the bar rack, you're going to end up spinning your wheels. SQUAT WIDE/NARROW Many get fixated on high bar vs low bar setups and, while there is a noticable change in stress by moving where the bar sits, it usually synonymous with changes in foot stance. Wherever your strongest 'competitive' stance is, that will be the main version of the lift for you. If you normally have a super wide 'Westside-ish' stance, then more narrow and upright squats can provide some range of motion to your lift and much needed love to your quads. If you squat like an Oly lifter by default, then taking your stance out will hit your glutes, hams and adductors along with requiring more of a tempo than you might be used to. FRONT/ZERCHER Front squats and zercher squats change the dynamic of a squat by a big margin. Front squats force you to squat more upright, causing the knee to track forward more and stressing the quads as a result. Supporting the bar across the collar bone puts a demanding stress on your upper back and midsection. If you've never worked front squats aggressively, I can gurantee sore back, abs and quads the day after. Zerchers put the load in the crease of your arms, which settles closer to your hips. That makes the glute action of extending the hips more important and taxes them more as a result. Similar to the front squat, the novel stress of supporting the bar in a different location is a recipe for a sore back and abs. Both, as it turns out, are phenomenal strongman accessory movements. PAUSE/ TEMPO Pausing at the bottom of a squat eliminates the stretch reflex, which is the bit of pop you get from bouncing out of the bottom. Stretch-reflex is a natural part of the movement and how we optimize force production (it's not 'cheating' as so many think). Taking it away, however, forces the nervous system to pull double time to get the same load moving from a dead stop. As you get better at paused squats, you should notice an increase in starting power with your regular squat setup. Those who use a bit of leg drive in their deadlifts will also notice an improvement in breaking the bar off the floor. Other benefits include more time under tension (which is great for hypertrophy and base building), reinforcement of technique and positioning and more stress on the supportive muscles of the upper back. Higher rep thresholds make these great as a 'Base' movement and low rep ranges with plenty of load play well into more specific 'Peak' phases. Slowing the tempo on the way down and/or the way up provides similar benefits of time under tension and reinforcing technique. Since 'Peak' training is all about conditioning the nervous system to fast efforts and heavy loads, leave tempo work to Base building in the early parts of training cycles. LOW/HIGH BOX Box squats are a method of interrupting the stretch-shortening cycle. They should be done under control with a pause at the bottom, relaxing the hip flexors to make sure that stretch-reflex dissipates completely. They are NOT to be done touch-and-go! There are two ways that I find them useful for most lifters: high box with a wide stance and low box with a more narrow stance. Putting the box above parallel is a way to shorten the movement and expose you to more weight. This can be very effective as a means of conditioning power output but, as fun as it is to load up as much weight as you can, you shouldn't go crazy with it. I like these with a wide stance because it shifts emphasis to the hips, shortening the movement into a tight 'snap' that gets faster as you improve. By the time you have the snap down and are leaping of the box, you should feel rock solid in your competitive squat AND your starting power on your deadlift. This is a specialized strength-specific variation that should be saved for later strength/'Peak' cycles. Low box is great for narrow squatters. It can be used to pause at lower depths, getting more range of motion and eliminating the bounce that narrow squatters rely on. We found it especially helpful in strongman, since so many events include going from a dead stop in a deep squat. The extra range of motion and disadvantaged joint angles make this a solid 'Base' exercise. BANDS/CHAINS Squats are a great candidate for accommodating resistance since humans are SO much stronger at the top of a squat than the very bottom. Overloading the top with bands and chains is a great opportunity to condition more aggression and follow-through for the entire movement and to expose the nervous system to weights it hasn't experienced before. There are a few different applications for using them, from heavy circa-max phases before a meet to snappier sets as part of speed or recovery work. This is one of those movements that can provid a big return IF they are applied correctly (and that's a big 'if'). The complexity of setting them up and finding appropriate ratios of straight-weight to band tension make them less appropriate for inexperienced lifters. If you do use them, make sure they come after the base building phase as part of a strength-specific block. SSB/CAMBERED There are a few specialty bars for squatting that play with where the load is. The Safety bar (or SSB Squat Bar) has a bend in it that shifts the plates in front of you, not unlike a front squat. This puts a TON of stress on the upper back. There was a rash of lifters turning the bar around and using them for front squats, likely because the pad made it more comfortable. The logic here is lacking, since the bend puts the weight behind you which is the opposite of a front squat. The SSB is more specific to a back squat than front squats while still providing much of the same benefits. I like these as a Base exercise, though lower rep thresholds might be good for weak point-specific targeting in a Peak phase with a lifter who tends to fold over with heavier squats. Cambered bars have the weight hanging down off the sides of the bar and tend to swing unless controlled with the hands. The swing provides a bit of a destabilizing effect but the main benefit comes from being able to keep the weight closer to the hips. Being able to pull the weight back as you scoop your hips forward takes a lot of stress off the upper back and midsection and puts it right into the glutes and hamstrings. This is a versatile tool that can be used during any phase of training. DEADLIFT SUMO/STIFF LEG/RDL/SNATCH GRIP These are all methods of changing your body position to disadvantage yourself in some way. A common myth is that 'some are built for sumo, some for conventional'. That's not true; everyone is more mechanically advantaged with their hips closer to the bar and an upright torso. The performance gap is determined by how much training you've done in that position. If you have only ever pulled conventional, wide stance deadlifts will be extremely awkward; that represents a great opportunity for some quick adaptation. If you work to bridge that gap, you will notice your glutes and hamstrings come into play much more. I see sumo pulls as being a good developmental tool for early and intermediate lifters, but are technically different enough that they will likely not have much carry over for more advanced conventional deadlifters. The awkwardness and limited load makes this a good Base building tool, but it will fall short in heavier phases as you get closer to competition day. Stiff leg pulls and Romanian deadlifts increase stress on the entire posterior chain by elongating the hamstrings and glutes at the start and pushing the hips further away from the bar. The subtle difference is that SLs are taken to the floor and allow for some round in the back (though not much) whereas RDLs don't touch the floor and emphasize very strict posture. The muscles around the torso have to work harder to stabilize and the muscles that extend the hip have to work harder to move you. I really like these as Base exercises; they adds mass effectively, build tolerance to volume and do so with weights that don't create the same recovery deficit. They also are really effective for teaching the 'hinge' movement, which is lacking in many lifters including some strong pullers. They should pop up regularly in novice and intermediate programs. Snatch grip deads became popular in the last few years when American deadlift record-holder (1,025lbs) and World's Strongest Man/Arnold Strongman regular Jerry Pritchett cited them as a staple in his training. Taking a wider grip reproduces a deficit-effect, since the lifter has to bend over/squat down farther to start the lift. There's another sneaky benefit here and that's the destabilizing effect the wide grip has on the upper back. If you can get comfortable hoisting substantial weights with a wide grip, your start on the deadlift will become deadly. This is another one I could see as a blanket Base exercise or as a Peak exercise that fixes a specific weakness, like a weak brace or a slow start. TRAP BAR/HACK LIFT These two movements change where the load is placed. Trap bars put the center of mass to the side of your body which represents a monster mechanical advantage. The lifter isn't limited by a bar having to move out and around the kneecaps so they can squat lower and keep the hips forward through more of the movement. Sheer overload is an obvious advantage but the use of leg drive is the real game changer. Many deadlifters have learned how to overhaul their start with more leg drive by incorporating trap bar pulls. Once working sets to exceed typical weights used with regular deads, the hip extension at the top of the lift gets hammered as well. That means sore glutes. I could see a trap bar pull as a solid Base exercise if blocks were used to increase the length of the pull. The overload that comes with higher handles is better for conditioning the lifter to sheer load in a Peak phase. I'm listing the hack lift as an example more so than a recommendation. The bar locks out right on your glutes if your arms aren't long enough and that makes the lift too awkward to be useful. Those with longer arms tend to be more advantage for deadlifts anyways, which kind of renders the hack lift ineffective. The lifter starts with the bar behind them, squats down and stands up with the bar behind their body. In principle, the hack lift increases the need for leg drive, just like a trap bar. It's a difficult version for sure, but trying to connect it to a specific weakness or stick point is difficult. Likely why it is almost never seen. PAUSE AT KNEE/TEMPO Same principle as with squatting: pauses reinforce strength and stability at that specific point and tempo reinforces technique/positioning and aids hypertrophy by increasing time under tension. Pauses with deadlifts can be done at a variety of points (right off the ground, above the knee at several points, on the way up, on the way down, both, etc.) but I really caution against going crazy with them; they will just end up as a distraction for most lifters. The most common pause point is either right below or a few inches below the knee on the way up, as that represents a very typical stick point in all-out deadlift attempts. That point can be a huge dead spot given that the hips are farthest away from the body and leg drive is pretty much absent. You will need to start light if you are new here, even as low as 50% of your deadlift. As you pull the bar and stop, counting through at least two Mississippi's, your abs and back will strain and your hamstrings will shake. Restarting the bar is much, much more taxing than you might anticipate soI like to think of two things: squeezing my abs hard to lock-down the brace and engaging my hamstrings and glutes as aggressively as possible to explode through the start. RDLs are the most common application for tempo deadlift work, but the conventional version can be done with a tempo on the eccentric phase. Slowing down the descent on working sets can be an excellent way to encourage hypertrophy (the negative component of a lift is usually associated with muscle growth) and build stability through the entire motion. If you aren't used to controlling the descent, it will be extremely taxing at first and that goes double for relatively strong deadlifters. Adjust the weight accordingly until you adapt. For strength specialization in a Peak phase, I've seen programs that utilize heavy negatives walked out of the racks with weight that is closer to (and sometimes beyond) a one rep max in order to stimulate the nervous system. As fun as this might sound, I would leave that to veteran lifters who have a tight handle on their recovery with deadlifts. Any maximal attempt with a deadlift brings the possibility of over-reaching and negatives increase systemic fatigue greatly. If you are unsure of where your recovery limits are with the main lifts or don't have a coach to determine that for you, this approach is likely to take more than it gives. DEFICIT/ELEVATED Standing on a 1-2" block when you pull is one of the oldest recommended deadlift accessory movements I can think of. I remember getting tips from an old 70's era powerlifter who said he would pull in thick work boots his entire prep and only take them off closer to a contest. The 1" or so elevation provided a small disadvantage and, since it was his footwear and not actual equipment, he wouldn't think twice about it. By the time the shoes came off, standard height felt like it was cheating. Specifically, deficits are used to fix weaknesses off the floor but the increased range makes them a good blanket Base exercise. For specialization purposes, make sure that the deficit doesn't force the lift into a different thing; once you get past two inches, those who have mobility issues will find themselves getting into a position that doesn't look anything like their standard pull. One of my biggest breakthroughs in the deadlift came from prepping for 2019 Strongman nationals where there was to be a 625lb axle deadlift for reps.... .from a 4" deficit. My poor bracing ability and tight hips at the time made this lift almost impossible; I remember pulling a single around 385lbs the first time and thinking "this just isn't gonna happen". I stuck to it for months, slowly progressing as I was able to inch my way to a better and better start position. I was able to touch the contest weight by the end and, once I returned to standard height, felt power and control off the floor that I have never felt before. My abs and erectors were so disadvantaged in that position that they had to grow substantially to compensate and that extra strength meant that, when getting into position, they stood a chance of winning when they were put into a tug-of-war with my excessively tight hamstrings. My new flexibility allowed for the most efficient setup I've ever had and my new ability to brace has insulated me from back pain and injury ever since. Elevated deads are a great general tool, as most strongmen know, since the top end of a pull can be loaded so much heavier. A lifter who regularly trains at 1316" bar heights will find themselves able to pull 10% or more at that height than from the floor while those who only pull from the floor might even be weaker at an elevation. If you are really poor at elevated deadlifts, use them with reduced weights as a Base builder. Once they become a reliable method of exceeding you typical working weights from the floor, use them to condition your nervous system in the Peak phase. BANDS/CHAINS Accommodating resistance is a popular supplementary work for deadlifts, as it reinforces compensatory acceleration (pulling hard through the whole lift) and conditions a strong, decisive lockout. If any part of your training features speed/recovery deadlifts with reduced percentages, there is nothing wrong with adding tension at the top and greasing the top end of your pull. For working sets, however, getting the band tension right and accounting for recovery with that extra stress at the top can be tricky. When you do have a better understanding of how to structure your split to pace recovery, heavier band pulls can be a great way for more developed lifters to prime their nervous system. AXLE/STIFF/DL BAR Bar stiffness has a huge effect on the developmental effect of the pull. Most bars have some amount of flex; it might be imperceptible but your body comes to bank on that to cushion the first inch or two of the pull. Once you switch to a bar with no give, like an axle, the difference becomes painfully clear. You can't yank the way a reactive puller might to get the bar moving (unless you're comfortable with a torn lat or bicep) and the extra fraction of a second needed to get the bar moving might as well be 3 full minutes. This unforgiving quality puts axle deads right up with deficit deadlifts as my preffered way to fix a laggy start and makes them my default for milking elevated or paused deadlifts for all they are worth. Actual deadlift bars, on the other hand, are half a foot longer and much thinner than a regular bar. This allows for a ton of give at the start and favors very explosive pullers. The bar will bounce and wiggle the whole way up, creating a ton of instability in lifters who aren't used to it but the whip ultimately allows seasoned pullers to move a lot more weight. You will always prioritize whichever bar is going to pop up in contest when you are working the Peak phase but keep in mind which lifts help what. An axle deadlift might help you as an accessory for a powerlifting meet with a deadlift bar, but training a whippy bar won't do much if you have an axle pull coming up in a strongman meet. BENCH WIDE/NARROW/NEUTRAL You can have more fun with pressing variations because upper body development benefits more from variety and you aren't at as much risk of blowing your systemic recovery for the week. The easiest way to vary your bench development is to change your hand position. Wide grip benches put the stress in the shoulder, requiring a lot more from the pectoral muscle. The pecs are big for starting strength and wide presses can help pad that part of the lift but be warned: extra stress on the shoulder joint means increased risk of overuse issues. Keep these as a Base movement for lighter weight until you are certain they are something you can recover from. They can theoretically be used in a Peak phase as well but given the rate of shoulder issues from frequent benchers, I don't think the juice is worth the squeeze. Close grip presses are so versatile that they should be considered for a permanent spot on your list. They disadvantage the elbow, spurring development of the triceps as a result. They can aid in both starting power and lockout strength and they tend to be friendly on the shoulders, even in the face of chronic shoulder issues. I like them for high reps in Base phases and I usually default to a close grip when doing other bench variations, like pin presses or pause work. If you have access to a Swiss bar, you can execute a neutral grip bench press. This provides good novelty for the sake of it but can also be used specifically to work around shoulder pain and target the long head of the triceps. This is another one that goes good with things like floor presses and general lockout work. INCLINE/DECLINE Incline and decline presses are used by bodybuilders to target the upper or lower chest but we generally don't care about that. These movements are useful to us because they work the same muscles through a movement pattern that is very similar to the bench press while being different enough to provide some neurological and structural recovery. Decline presses can be an effective overload tool, but I don't know a ton of big pressers who lean on them as a main variation. That's probably due to the fact that decline benches aren't normally found outside of corporate gyms and that there are better ways to overload a bench than crawling into a guillotine belly up. Incline presses, on the other hand, are very versatile. They serve as yet another potential workaround if flat benches bother your shoulders, they increase the range of the press substantially, they target the front delts more aggressively AND they have carryover to overhead pressing. I've incorporated incline pin presses and incline close grip presses with quite a bit of success in the past, increasing lockout strength while giving my shoulders a break from full-range benching. They are a solid Base option but should be switched with flat variation if your Peak phase is heading towards a powerlifting meet. PAUSE/TEMPO Tempo work is fantastic for building hypertrophy in the upper body. Slowing down the press and the descent introduces more mechanical tension to the set, increases time under tension and builds up a TON of fatigue. It's great Base work but not specific enough to the aggressive work with heavier loads that needs to be done in a Peak phase. Pause benches build up starting strength and reinforce position the same way that pause squats do. If you are a competitive powerlifter, I believe pause benches should be your default anyways. It feels good to rebound a lot of weight to arms length after slapping it off of your sternum but that becomes a crutch that will be difficult to ditch if you have to prep for an actual meet. SPOTO/FLOOR/DEFICIT/BOARD/PIN There are a lot of ways to change the height of a bench press. Deficits can be used by putting Fat Gripz on the bar or using a buffalo bar, although this requires having bulletproof shoulders. Spoto presses involve stopping the bar an inch or so above the chest, sometimes with a pause. This requires an extra bit of control and is hugely productive to building comfort and strength right off the chest. It also can be a tool to avoid overuse of the shoulder joint. These are versatile and can be used at any point during your training. Partial bench movements are used to work stick points and/or expose the lifter to overload. They all do this well but differ slightly in how you support the load at the bottom of the movement. Floor presses have you lying on the floor and resting your upper arm on the ground. I treat these like a box squat, relaxing tension at the bottom so I can fire into it from a dead stop. These are hugely beneficial for lockout work and carryover to overhead presses as well. Board presses require a Bench Block or a friend holding a board on your chest. The bar deloading into the board and through your chest is different; it feels closer to a regular bench press and reversing direction feels more natural. Pin presses involve resting the bar on the pins of a bench or squat rack. I really like starting these at the very bottom of the press, otherwise known as a dead press. My blanket recommendation for elevated benching is to keep the height reasonable. Really high board presses are great for priming the nervous system for heavy lifts and fixing lockout-specific weaknesses in a Peak phase but this is something only more developed and specialized bench pressers should incorporate. Intermediates should instead do pin and board presses from 2-4" off the chest, incorporating touch-and-go or shorter pauses as part of Base phases and longer holds or bottom-up work in strength-specific Peak phases. BANDS/CHAINS I strongly recommend non-elite bench pressers avoid accommodating resistance. That's not because it doesn't have value for intermediates but because setting up for the right amount of load at the right part of the lift is really tricky given such a short range of motion. It's really easy to use too much band tension and blow your wad or too little to where the effect is negligible. Generally, those trying to fix their poverty bench have imbalances in their physique that need to be addressed, need more mass and need a more consistent technical setup. All of these should be addressed before spending 20 minutes finding the right band to weight ratio. TSUNAMI BAR/BANDBELL/AXLE Specialty bars can change the dynamic of the bench press quite a bit, causing new adaptations. Tsunami bars, or just hanging weights from bands if you don't have the coin, create a ton of instability and will test your ability to maintain position. It's a very non-specific movement, so it should pop up in a Base phase with a steady tempo on the concentric and eccentric. These were actually a life saver when I was dealing with a shoulder injury a few years back; I didn't need a lot of weight to tax the working muscles and with high effort it seemed to bypass any shoulder pain. Axle presses create a subtle change in how the load is distributed through the elbow and shoulder. With the hands open more, the forearm muscles can be tensed very easily and this creates a lot of tension at the elbow joint. The result is more tricep activation and a sense of control over the bar. The change isn't monumental but it can be a nice change up from time to time, especially if you are dealing with elbow issues or have trouble squeezing the bar through the change of direction. Use Fat Gripz on a regular bar and you get the additional benefit of benching to a deficit. OVERHEAD WIDE/NARROW/NEUTRAL Wide overhead presses absolutely annihilate the delts. It also forces your elbows out to the side, which transfers some of the load from the front to the lateral head of your delts. Add to that the fact that you don't need very much weight to make these work for you and it's obvious that wide presses are a great Base exercise. A narrow grip with the thumb right outside the shoulders usually represents the default 'competition' grip (even though you probably aren't competing in a standing strict press) given that the extra compression at the elbow gives you the strongest break at the start. It isn't productive to go narrower than that, so 'narrow pressing' as a variation should only be used for those who do most of their main pressing with their hands closest to the rings. A neutral grip with a Swiss bar will put more of the load on the long head of the triceps and will provide a change in neurological stimulus for the sake of it but that's about it. I don't love Swiss bar since the depth of the handles force the weight out in front, compromising the load by making positioning more awkward. For the trouble, I would just as soon use a log. But then again, I'm a strongman so I look for any reason to use a log. BTN PRESS Many professionals claim that behind-the-neck presses are inherently bad for your shoulders. I tend to believe that most injuries with this movement are a result of the same bad habits that lead to all other injuries: poor mobility, reckless technique and too much damn weight. That being said, I'm not going to discount the anecdotes of shoulder injuries from these because lifting can very much be degenerative and I know how not-fun torn labrums and strained rotator cuffs can be. Approach them how you would approach benching, deadlifts or any other lift that that has a history of eating people up who didn't treat them with proper respect. Start light. Progress slowly. Stay short of failure. Evaluate how you feel post workout. Do not be a hero. If your shoulders can handle the movement without issue, these can be an absolutely devastating upper body builder. The low weight and absolute control I recommend you apply to these makes this an obvious candidate for Base phases. PAUSE/TEMPO If you bounce your reps on strict presses (as I advise you do), pausing at the bottom can be a nice change up. The reason I don't recommend pausing as your default strict press strategy is because each start takes a ton of effort in a standing press; this requires a drop in load that hinders total volume on anything over 5 reps. For building starting power in a Peak phase over 3-5 reps, it works great. Pauses at different heights can reinforce positioning, target stick points and increase overall time under tension. The most common stick is going to be somewhere between your nose and forehead, so that can be a good default range to work in, even if you are just using it for blanket novelty. Tempo work is an easy way to make lighter weight more challenging in Base phase and I recommend BTN and wide presses have a slowed tempo by default. PIN/LOG/PUSH PRESS These are all methods of overloading the top of the lift. Pin presses are great for building starting power and can involve a lot of overload if you do them seated. There isn't an eccentric phase (or at least, there doesn't have to be) which makes them easier to recover from than movement where the negative has to be controlled. These tie in nicely to a strength-specific block in a Peak phase. Log presses are a solid variation regardless of whether you compete in strongman or not. The neutral grip with the elevated hand position allows for a lot of overload here but the fact that it is forced so far out in front of you can be overwhelming at first. When you are new to log presses, you will be using pretty paltry weights. When you get good at them, you will likely be pressing more than you can with a barbell. Improvements in the log press are usually associated with a stronger upper back and stronger triceps. You can do them strict or with a push press and they can be used at any phase of training. Barbell push presses are near and dear to my heart since they are my main competitive movement. Lifters who are new to push presses will feel worse for doing them. The weight won't exactly move quick and a ton of energy will be spent trying to control the pace. As time goes on, efficiency will improve which results in more load which results in sudden spurts in strength and size. Getting the overload benefit out of a push press requires some technical mastery first. I suggest newer lifters experiment with them during developmental Base phases while heavy, low rep work be saved for the Peak phases of more advanced overhead pressers. BANDS/CHAINS As with benching, yes it can provide benefit with speed and lockout strength but, damn, is it a pain to set up for the return it gives. If you are a very specialized presser who is experienced enough to put it together (or have a coach who is), fantastic. For everyone else, keep it simple. TSUNAMI BAR/BANDBELL Tsunami bars and weights hung from bands expose poor stabilization with overhead presses. The lift, by nature, is less stable than something like a bench press so I think this variation has a ton of potential benefit here, as developmental tools in Base phases and as a form of injury prevention or rehab. Keep the reps high and weight conservative and you will feel what I'm talking about. ACCESSORY I spent a lot of time writing out the variations for the main lifts because knowing how they effect your training is crucial for using them surgically in a program. The smaller accessory movements that come towards the end of the workout are more generic and mainly just need to be included for the sake of extra work. This is how I group accessories and isolation work along with a few of the most productive options for them. The finer points of technique are way beyond the scope of this book but your favorite search engine will clarify any questions inside of 30 seconds. Don't get lost down that rabbit hole, though; you can spend all day comparing meaningless technical minutiae and you aren't better for it. You can surely scour the internet for exotic variations using cables, dumbbells or machines but remember that your goal isn't to have the most creative list of assistance exercises. Unless any one of these causes a particular issue, stick to the basics and work them long enough to get good at them. COMPOUND ACCESSORIES These are movements that use more than one joint. They can be prescribed because you are trying to target a particular muscle group or you can schedule them by which main lift they contribute to. The recovery cost with these is much lower than with barbell squats, presses and pulls and should be done for more sets and with more effort. BACK Compound back work consists of rows, rows and more rows. For your upper back, they are like water to a weed and are vital to the development of a torso that is capable of sustaining monster presses and deadlifts. Sometimes, they are better strict, sometimes I like some body English. Treat them with the same intent to progress that you would treat a bench or a squat. • Bent Barbell Rows, One Arm Dumbbell Rows, Plate Loaded Machine Rows, Lat Pulldowns, T-Bar Rows, Chest Supported Rows, Seal Rows BENCH Once you break away from barbells for your bench variations, the recovery stress drops quite a bit. These movements still provide a huge growth stimulus and can be chosen or tweaked to emphasize your pecs, delts or triceps. Use the same control you would on a bench and, though you can work these harder, avoid sloppy or grinded reps. • Dumbbell Bench Press (Flat or Incline), Smith Machine Bench, Machine Chest Press (Wide, Narrow, Incline or Decline), Weighted Push-ups, Parallel Bar Dips OVERHEAD PRESS There aren't as many options for rounding out your overhead press and that's not a bad thing. Between benching, your main overhead work and all of the potential variations and isolation movements, your shoulders don't need more ways to grow. Use these for higher reps and to build more fatigue than you would on the barbell versions. • Dumbbell Overhead Presses (Seated or Standing), Machine Shoulder Presses, Parallel Bar Dips SQUAT These movements should play a much bigger role in your development, especially if you are newer or if you are in a Base phase. Barbell squats can be brutal but the fact that so many muscles are involved means that the legs usually aren't the limiting factor. These movements put much more emphasis on the muscles of the leg which allows you to build more local fatigue than you could with a barbell. Treat these with a sense of urgency and the difference will be clear. • Leg Press, Lever Squat, Hack Squat, Lunges, Split Squats, Hip Belt Squat DEADLIFT Similar to the squat accessory, these allow more fatigue in specific areas than a conventional deadlift by itself. Stay braced and controlled and practice forceful execution with the hips. • Good Morning, Seated Good Morning, Glute Bridge, Dumbbell RDL ISOLATION ACCESSORIES DELTS • Front Raise, Lateral Raise ** Either one can be done with dumbbells, bands or cables. PECS • Dumbbell Flys, Cable Flys, Pec Deck Flys, Dumbbell Pullovers ** Flys with chains are one of my favorite accessories. BICEPS • Hammer Curl, Reverse Curl, Dumbbell Curl, Barbell Curl, Machine Curl TRICEPS • Skull Crushers, French Press, JM Press, Pressdowns, Kickbacks, Bench Dips, Tate Presses • TRAPS/REAR DELTS/ROTATOR CUFF • Seated Dumbbell Cleans, Bent Dumbbell Raises, Rear Pec Deck Flys, Band Pullaparts, Face Pulls, External Rotations QUADS • Leg Extensions, Backwards Sled Drags ** Most quad exercises will be compound movements. GLUTES • Weighted Back Extension, Glute Bridges, Donkey Kicks, Cable PullThroughs, Kettlebell Swings HAMSTRINGS • Hamstring Curl, Nordic Ham Curl, Glute Ham Raise, Hamstring Rollouts ERECTORS • Reverse Hyper, Weighted Back Extensions BRACING/ABDOMINALS • Planks, Side Planks, Bird-Dogs, Curl Ups, Dead Bugs, Pallof Presses, 90/90 Breathing, Situps, Hanging Leg Raises ORGANIZING THE TRAINING WEEK We want to start our program by first establishing a baseline of weekly work. Once this is set, we can plan how we are going to move stress up over a period of weeks. This is what a training week has to include. - Main Lift - Variations of the Main Lift - Accessory Movements - Any other relevant recovery or conditioning work The lifts you select and how much work you are going to do in each area will depend on where you are in your cycle. Remember, blocks get arranged broad to narrow, base to peak. I'm going to cover a couple of quick examples of training splits to illustrate a spectrum. Where your split falls on the spectrum will impact all of the other training decisions you make, from how heavy and hard each workout is to how many variations and accessory exercises you can do. HIGH FREQUENCY Higher frequency methods require a whole-body template. The main exercises, or some close variations, are used as the primary means of development and that stress is distributed over the entire training week. Many general strength programs for novice/intermediate are high frequency, such as Starting Strength, Greyskull LP and the Texas Method. The benefit is that you get many more weekly touches with each movement so skill acquisition can occur faster. The frequency can also exploit the fact that less developed lifters recover from hard efforts faster; instead of weekly jumps, novices can sustain weight increases every few days. It is also now common for more specialized and advanced powerlifting programs to be high frequency. Olympic lifting shows it's influence here as many international coaches were inspired by the data collected from the Soviet era. Oly lifting is, by nature, a high frequency sport; it involves explosive movements that are A.) easier to recover from and B.) extremely technical and both of those factors make daily practice requirement of elite performance. Mike Tuscherer and Boris Shieko are two of the most visible examples of coaches who boast successful high frequency systems. They both use a mix of upper and lower body competition lifts (or close variations) in each workout and mainly differ on how they prescribe sets and reps. Mike T generally prescribes top sets for each exercise according to his RPE scale where Shieko rolls the weight up and down differently in each workout according to more complex charts influenced by Olympic lifting data. HIgh frequency programs are about as proven as it gets in their effectiveness but they feature their own set of rules and their own list of potential pitfalls. EFFORT Effort has to be controlled tightly in a high frequency program less the entire structure of the program go out the window. With the exception of complete novices, you can't squat, press and deadlift 3 times per week to limit and expect to meet your prescribed numbers each workout. Mike T addresses this by using an RPE scale to select appropriate working weights for each exercise; the lifter only puts the weight on the bar according to their abilities that day. Shieko uses advanced volume distribution charts derived from decades of observing elite athletes that bounce between large, medium and small workouts. Even simple programs like the Texas Method address this by varying the workload day to day to make it sustainable (one heavy day, one volume day, one recovery day). VARIETY In each workout, something has to change workout to workout to keep the workload sustainable. High frequency programs will always feature some difference in each workout, whether it's a change in movement pattern, change in volume/intensity or change in effort. When controlling for recovery, remember that variety offers a form of it. If you are working in the same set and rep threshold 3 days per week you can move between 3 different variations to allow consistently high performances while encouraging well rounded development. Example: Top 2 @ RPE 8 Bench Press Top 2 @ RPE 8 Close Grip Top 2 @ RPE 8 Pause Bench If the protocol is specific to the exact movement, then you can switch between more volume/hypertrophy and intensity/strength thresholds (also called DUP) to accomplish a similar effect. Example: Squat 3x8 @ 70% Squat 2x5 @ 80% Squat 5x3 @ 85% Protocols similar to the Texas Method will take what is, arguably, the simplest route and change the effort while keeping the lift and threshold the same. Example: Squat 3x5 @ 75% Squat 2x5 @ 65% Squat 1x5 @ 80% The point is that some amount of undulation is necessary with high frequency programs. How complex it is should hinge on your own goals and experience along with your access to quality coaching. ACCESSORY WORK There are plenty of opportunities to incorporate movement variations with high frequency splits but the total number of non-specific accessory exercises will be very limited. Simply put, you can't squat and deadlift 3 times per week and expect to follow it up with RDLs, back extensions, hamstring curls and lunges. Most of the work will be from the main movement and close variations. That means that high frequency work is innately more specialized than lower frequency options that can accommodate a greater volume of non-specific accessory exercises. This is an important distinction for those new lifters who would be best suited by rounding out their physique and developing a large base of muscle. The tendency for early lifters to jump straight into a high frequency routine represents the trend of over-specialization I was talking about earlier. As a general recommendation, less developed lifters should take the opportunity to prioritize a wide base and that means choosing a split that allows a lot of nonspecific movements to be done with ample volume. Don't wait for tiny triceps, flat quads or invisible lats to be the thing holding your progress back; make them a priority FIRST and then put them to work as you specialize. As the base becomes increasingly wide and numbers start to get competitive, you as a lifter stand much more to gain out of a more specialized high-frequency split. EXAMPLE: Starting Strength / Texas Method / H/L/M Starting Strength - A/B Split (A) Monday Squat 3x5 Bench 3x5 Deadlift 1x5 (B) Wednesday Squat 3x5 Press 3x5 Clean 5x3 (A) Friday Squat 3x5 Bench 3x5 Deadlift 3x5 Starting Strength (example above) is the most popular default novice program. What makes a high frequency program more oriented towards novices versus intermediates is the rate of progression more than how the exercises are distributed over the week. SS keeps the sets and reps fixed and simply adds a small amount of weight every session for months on end, which can't be done with stronger lifters. Texas Method Monday Squat 5x5 Bench 5x5 Deadlift 1x5 Wednesday Squat 2x5 Press 2x5 Chins 3x5 Friday Squat Max 5 Bench Max 5 Cleans 5x3 *Bench workouts alternate with press workouts Once a lifter treads into intermediate territory, recovery has to be accounted for by varying effort and training thresholds. Texas Method (above) accommodates intermediates by alternating between volume and intensity efforts on Monday and Friday and using Wednesday as a recovery day. The rate of progression now slows as weight is added every week instead of every session. Heavy/Light/Medium Monday Squat (H) Deficit DL (M) Wide Bench (L) Wednesday OH Press (H) Front Squat (M) SL Deads (L) Friday Deadlift (H) CG Bench (M) Pause Squat (L) *Bench workouts alternate with press workouts Heavy/Light/Medium (above) looks similar but can be modified further to individualize the program to intermediates. The stress can be distributed better by staggering the heavy, light and medium efforts across the week instead of having them all on one day. Variations are also often substituted to increase specialization and better attach weak areas that pop up as lifters become more developed. The detailed perameters of each program is beyond the scope of this book. Check out Andy Baker's Youtube channel for more information. EXAMPLE: Reactive Training Systems / Shieko Templates Shieko Novice Template Monday Wednesday Friday Box Squat DB Bench Flies Pullups Leg Raise Incline Bench Pushups Rack Pulls Lunges Back Extension Box Squat CG Bench Flys Good Mornings Play Sports *** changes weekly Notice that this counters the minimalist movement selection seen in Starting Strength and similar novice programs. This varied approach is similar to what coaches of young athletes do and it is here that we see the academic approach of sport development influencing Shieko's methods. There is exposure to a lot of different movements and they are selected based on how well they will generally develop the lifter and prepare them for the main lifts down the road. This is what I am aiming for with the novice program I outline later in the book. Shieko Intermediate Template Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday Front Squat Bench Press Squat Pause Deadlift Bench Press Pause Deadlift Bench Press Squat Board Bench Deficit DL Incline 13" DL Chest Acc. Abs Lat Acc. Good Mornings Chest Acc. Back Ext. Dips Leg Press *** changes weekly The intermediate templates Shieko writes usually feature 3 big lifts (often with the first lift being repeated as the third) followed by several smaller developmental exercises. RTS Generalized Intermediate Program Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday Squat Comp Bench Pause Bench Deadlift Floor Press Front Squat Pin Squat Bench Press Push Press Deficit DL CG Bench SLDL *** changes weekly RTS and Shieko programs both use a mix of main movement and close variations and often change the variations each week. They decide how to distribute them across the week according to what will best permit recovery (not a lot of hard rules here) and then apply their preferred methods of progression. RTS uses a set hierarchy of movements, selecting a primary, secondary and supplementary movement for each lift and using them along with assistance lifts to populate the week. Shieko has a long list of his preferred movements (present in his Powerlifting Foundations and Methods book) and treats them more similarly by not committing to any one for a particular block. Shieko has some peculiarities, like programming the same lift at the beginning and end of the same workout (i.e. Bench, Deadlift, Bench) and, where Mike T. emphasizes barbell movements, Shieko is more liberal with machine work and isolation movements. Besides that, there don't appear to be meaningful differences in training organization between the two. I like to use Mike Tuscherer and Boris Shieko as examples because they are two well known and highly regarded coaches. Keep in mind that there are plenty of coaches and systems out there that use similar methods and will have their own preferences. Don't make the mistake of seeing the small idiosyncrasies of each program as represent some gold standard. LOW FREQUENCY 1x per week strength splits mirror simple bodybuilding routines, with the main difference being that muscle groups are arranged by lifts. A lot of young lifters back in the day grew from workouts inspired by Flex and Muscular Development and some of the best powerlifters of all-time arranged their training similarly. 'Powerbuilding' is the term used for bodybuilding workouts that get repurposed for strength development and the idea is that both size and strength can be optimized when they are trained for concurrently. EXAMPLE: Generic Powerbuilding Routine Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday (LEGS) (CHEST/BIS) (BACK) (SHOULDERS/TRIS) Squat Front Squat Leg Press Lunges Leg Ext. Bench Press Incline Bench Machine Bench DB Fly Hammer Curl DB Curls Deadlift Good Mng. GHD Hamstring Curl Bent Row Lat Pulldown Strict Press BTN Press Dips Lateral Raise Skull Crusher Dip Machine The goal is to exploit the main lift as a strength-specific developmental tool by applying some proven strength progression then backing it up with loads of hypertrophy work using variations and accessories. Notice that the order of movements go from big to small; where true bodybuilders don't care about prioritizing heavy weight first, those looking for improvements in a 1 rep max save the high-fatigue work for the end. Some strength programs that use a similar split might be more specific in their exercise selection, but powerbuilders usually choose the exercises and rep schemes based on their general muscle building ability rather than their capacity to fix specific weak areas of the lift. The thinking goes that weaknesses won't pop up if general development is always the main priority. EFFORT Low frequency splits don't require such a tightrope of recovery to be walked to be effective. In fact, the full week in between similar workouts usually warrants as much local muscular fatigue being built up as possible. This gives a big cushion to less experienced lifters. The big downfall will be with those who struggle to take smaller exercises seriously and last through very long sessions. I have come across even highly competitive lifters who can grind through vein-popping deadlift attempts but won't push a set of leg presses to save their life. This is a specific flavor of training that isn't everyone's cup of tea, but I still think everyone should become familiar with at some point. If you get in the habit of looking down your nose at anything that isn't a barbell movement, you will procrastinate down the road when increased volume with targeted isolation movements is the only way to fix the weak points that are holding you back. VARIETY A hallmark of low frequency approaches is the variety of rep and percentage thresholds that get worked through in a single workout. We already covered how this variety is a devastatingly effective way to grow mass and build a wide base but there is a trade off. Because you will only have one crack at each main lift each week, there won't be a ton of variety in the rep and percentage range you will be working them in. In a low frequency split, either the main lifts persist as the designated 'low rep strength' movement indefinitely or it gets moved through different rep thresholds over time, like a linear or block periodization approach. Unless you are right up against a contest prep, one isn't really better than the other. For most non-advanced lifters, I like 'forever programs' like 5/3/1 that keep the main lift on one progression and designate variety to the secondary exercises. It works well enough and doesn't offer a lot of opportunities to mess up. For those who want to get a taste for the deliberate and aggressive changes in training that comes with linearly periodized approaches, Juggernaut is a good low frequency example. ACCESSORY WORK The main appeal of a low frequency split is the ability to prioritize accessory work to build a wide base. Embrace this as an advantage and take the smaller exercises seriously. The full week of rest has to be earned and that means building up enough local fatigue to merit the time off. Smaller movements can be trained much harder without causing the systemic fatigue that hinders subsequent workouts. In fact, they typically have to be trained hard to illicit the desired result. If everything after the main exercise is treated lackadaisically, you might as well just commit to a higher frequency split. To keep the triceps, rear delts, lats, hamstrings and other trouble areas growing in step with your main lift, progressive techniques have to be employed. I have some simple rep progressions laid out later that will take the guess work out, along with some fun (or not so fun) advanced fatigue techniques to force growth out of stubborn areas. MIDDLE FREQUENCY Twice per seek splits for each lift seems to be the most common method of training organization across the board and I find them to be the best generic recommendation for most lifters. The higher frequency of 2 days gives you extra touches to help with skill acquisition without being so high that accessory work has to be limited. There are a lot of ways to program twice per week. You can keep it to the main movements or be liberal with variations. You can focus on one upper body and lower body lift for a full cycle (say, bench and squat) and use their rival lift as accessory. My preferred method is a blended split, as each day features a main movement blended with it's rival's variation to keep volume and effort consistent for all lifts across the board. UPPER LOWER UPPER LOWER BENCH SQUAT PRESS DEADLIFT PRESS VAR. DL VAR. BENCH VAR. SQUAT VAR. 1x per week programs have some overlap, since the upper body and lower body days use the same muscles and similar movement patterns. We can use that to our advantage by committing to give equal love to both lifts on each day. Squat days won't be entirely knee-dominant now, so the crippling fatigue we get from 2 hour squat marathons will be muted (fun as it is to plan your deadlift day around squat DOMS). The potential amount of work across all exercises will be the same and you will be more fresh for each main lift and variation, which should actually equate to greater weekly volume from better performances. I really like this because it puts you in the middle of all the options so you won't get whiplash if you jump into a more specialized high-frequency plan. I think it's important to pick lifting methods that will teach you something about what you are going to experience later on. If we can do that while preserving our ability to make simple and straightforward progress, then it's a no-brainer. STRUCTURE - SQUAT/DEADLIFT DAY 1 1. 2. 3. 4-5. SQUAT DEADLIFT VARIATION SQUAT VARIATION or COMPOUND SQUAT ACCESSORY SMALLER ACCESSORY - HAMS/QUADS DAY 2 1. 2. 3. 4-5. DEADLIFT SQUAT VARIATION DEADLIFT VARIATION or COMPOUND DEADLIFT ACCESSORY SMALLER ACCESSORY - HAMS/QUADS This is a solid guideline for structuring your training. It is hard to screw up and it gives a whole lot of play in the joints for tweaking. Spots 1 and 2 are the bread and butter, the main lift followed by a variation for it's opposite. Spot 3 can be filled with another variation of the main movement or by another compound exercise that hits the same muscles or movement pattern. In the Day 1 example, we went with leg presses as a simple accessory option, but we just as easily could have prescribed another squat variation like pause or wide stance squats. 3 big compound movements is plenty for any workout, regardless of how advanced you are. Day 2 features the deadlift emphasis. Notice that the small accessory movements are the same as Day 1. I like to glue myself to the same isolation movements until I feel like I've improved but this is optional. You can feature a different run of movements on each day for the isolation work. STRUCTURE - BENCH/PRESS DAY 1 1. 2. 3. 4-7. BENCH PRESS OVERHEAD VARIATION BENCH VARIATION OR COMPOUND ACCESSORY SMALLER ACCESSORY - BACK/DELTS/PECS/BICEPS/TRICEPS DAY 2 1. 2. 3. 4-7. OVERHEAD PRESS BENCH PRESS VARIATION OVERHEAD VARIATION OR COMPOUND ACCESSORY SMALLER ACCESSORY - BACK/DELTS/PECS/BICEPS/TRICEPS The upper body has more moving pieces, so we are using 7 exercises to cover all of the bases. I know it looks like a lot to most of you. It's really not. The first 3 movements are all compounds and will go by pretty quick; a half hour or so if you aren't stalling in between sets. Towards the end, fatigue will be setting in and you will be looking for reasons to skip the isolation work. These smaller movements aren't nearly as taxing; you should be able to run a marathon and still knock out a set of lateral raises right after. If you do skip the work, remind yourself that it was out of poor planning or unwillingness to work, not because it was an unreasonable amount of effort. Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday 1. 2. 3. Squat 13" Deadlift Leg Press Bench Press OH Pin Press DB Incline Deadlift Front Squat Good Mng. Strict Press CG Bench Bar Dips 4. 5. 6. 7. Hamstring Curl Leg Extension Cable Row Front Raise French Press Hammer Curl Ham. Curl Leg Ext. DB Row Lateral Raise French Press Reverse Curl You absolutely can consolidate work at the end to get through it faster. Any of the exercises from number 4 on can be done in superset; go from one right into the other and then rest for 1-2 minutes. If you do that over all of the small accessory movements, the workout will run less than an hour. As a general rule, novices don't need as much work with compound movements to get a good training result. The main movement and one developmental variation will be enough, leaving plenty of time to focus on rounding out their physique with varied movements and smaller isolation exercises. All of the compound lifts can be treated interchangeably and worked with similar difficulty. Intermediates can use 3 main compound movements and will want to start surgically selecting their variations and accessory movements based on perceived weaknesses. Instead of the volume being distributed evenly, perceived weak areas will have more total sets dedicated to them each week. This is where like movements have to be varied. A heavy/light or volume/intensity approach can be used to make sure the work week is sustainable. Advanced lifters are the best candidates for more specialized high frequency approaches but plenty have developed using a low or medium frequency split. They will want to keep smaller developmental movements to their Base phases, which will get shorter, and use Peak phases almost exclusively for drilling form and weight with the main movements and their variations. Any lifter who is knocking on 'advanced' status should, by default, consider a 910 day split instead of a 7 day split. Here are two quick methods for writing that out. Option 1: Write 3 workouts to cover all of your bases, focusing on one exercise per workout. Then, re-write those 3 days in a different training threshold to make a 6-workout 'week'. Cycle through those 6 days using a 4 day per week split. EXAMPLE: (1) Volume vs. (2) Intensity 4x5 5x6 4x8-12 SQUAT 1 BENCH 1 DEADLIFT 1 Pause Squat Front Squat Accessories Wide Bench CG Bench Accessories Axle Deadlift Snatch Grip Deadlift Accessories Top 3 3x4 4x8-12 SQUAT 2 BENCH 2 DEADLIFT 2 Squat Box Squat Accessories Bench Board Bench Accessories Deadlift Rack Pull Accessories Monday SQUAT 1 Wednesday BENCH 1 Friday DEADLIFT 1 Saturday SQUAT 2 Monday BENCH 2 Wednesday DEADLIFT 2 Friday REPEAT Saturday There are multiple ways to include variation of movements, thresholds and effort to make a split sustainable, this is just one. Option 2: Keep your 4 workout cycle and train them inside over 3 days instead of 4. Monday . Squat 13" Deadlift Leg Press Accessories Wednesday Bench Press OH Pin Press DB Incline Accessories Friday Monday Deadlift Front Squat Good Mng. Accessories Strict Press CG Bench Bar Dips Accessories This option is the easiest but leaves a lot of down time throughout the week. Instead of sitting on your heels, rest days can be filled with smaller workouts to focus on weak points or GPP work. METHODS OF PROGRESSING Mapping out a sustainable work week is the first step. Now you need to know how you are going to increase the stress of the workout over time. There are a lot of different training approaches and I want to give insight to them without flooding you with a bunch of unnecessary trivia that will ultimately make it harder for you to make a decision. I think of 2 broad program types for progressing over time: progressive-based programs and static programs. PROGRESSIVE PROGRAMS Progressive programs are what you will be more familiar with; they are much more abundant because they are user friendly and look cleaner on paper. You would think how a program looks on paper would be irrelevant to how often it gets prescribed but, unfortunately, you would be wrong. A progressive program is one where the workout changes every session based on some obvious progression. You can, for instance, line up all of the deadlift workouts in a month of training and see that the weight goes up, the volume increases or something else happens week to week to make the stress goes up. NOVICE LINEAR PROGRESSION This is the shortest answer to the question of progressive overload: keep exercises, sets and reps the same and only focus on adding a small amount of weight. A simple linear progression might start your bench at 135lbs for 3 sets of 5 and prescribe a 5lb jump every session for as long as you can complete your reps. For novices, this process can go on several times per week for months, which is why they are usually prescribed as a fool-proof way for novices to develop a foundation of strength. EXAMPLE: Monday Wednesday Friday Monday Squat 3x5 @ 150 Squat 3x5 @ 155 Squat 3x5 @ 160 Squat 3x5 @ 165 Starting Strength is the most common example but it's important to note: novice linear progressions work well for novices but specifically don't provide enough recovery or variety for more advanced lifters. WEEKLY LINEAR PROGRESSION We already gave examples of the Texas Method and H/L/M as being the intermediate stepping stones once you've outgrown novice linear progressions. These programs have a similar weekly split but make the weight jump on a weekly basis instead of a daily one. The rest of the workouts are replaced with lighter efforts or a different rep range and the end result is a sustainable method of progressive overload for intermediates. (repeat +5lbs) Monday Squat 5x5 @ 150 Wednesday Squat 2x5 @ 130 Friday Squat 1x5 @ 170 Monday Squat 5x5 @ 155 Wednesday Squat 2x5 @ 135 Friday Squat 1x5 @ 175 Note that weekly linear progressions can be applied to low frequency splits as well. WAVE PROGRESSION This is one of my favorite methods since it works for a wide variety of skill levels and does well to break up training monotony. Instead of inching forward your best 5-rep set, waves move you through a range of work over a block. The wave then resets with a few more pounds on the bar and repeats. In novice programs, the rate of progression is several days. With the first intermediate progressions, it's every week. A wave bumps it to several weeks which fits nicely with the recovery demands of more advanced lifters. 5/3/1 is the best known example and Juggernaut actually uses a pattern of it as part of it's broader linear structure. (repeat +5lbs) Week 1 1x5 @ 200 Week 2 1x3 @ 220 Week 3 1x1 @ 240 Week 4 1x5 @ 205 Week 5 1x3 @ 225 Week 6 1x1 @ 245 STEP WAVE PROGRESSION / VOLUMIZING Step loading keeps the weight the same for several sessions and increases stress by adding a set or rep. This method is little talked about, which is funny because it is extremely effective and very appropriate for newer lifters. Pavel Tstatsouline and strength legend Doug Hepburn both have promoted forms of step loading programs in the past. By default, I prefer it to be structured in a wave format where the number of sets build up over several sessions before dropping back down and being repeated with a heavier load. The short term stress of dealing with more and more work creates volume-specific adaptations (namely, mass) and the extra time in between weight increases lets you focus on technical mastery over several sessions. (repeat +5lbs) Week 1 3x5 @ 200 Week 2 4x5 @ 200 Week 3 5x5 @ 200 Week 4 3x5 @ 205 Week 5 4x5 @ 205 Week 6 5x5 @ 205 This is a very slow 'forever program' approach if you want to progress out of novice territory while turning your brain off. A few months of this will leave you much stronger than when you started and you will spare yourself the hell of endless grinded 3x5s with 5 more pounds. I like to add an element of complexity to this for faster short-term development by adding weight and sets within the 3-week time frame, then taking each wave through different rep thresholds. It's a method of progression that optimizes volume increases, so I just call it 'volumizing' (in Base Strength it was labeled as "My Favorite Base Phase") Week 1 3x12 @ 55% Week 2 4x12 @ 55-60% Week 3 5x12 @ 55-65% Week 4 3x10 @ 60% Week 5 4x10 @ 60-65% Week 6 5x10 @ 60-70% Week 7 3x8 @ 65% Week 8 4x8 @ 65-70% Week 9 5x8 @ 65-75% This is more appropriate for intermediates than complete novices; the waving of volume along with the ability to work in a range depending on how you feel that day allows for recovery that novices don't really need. The first week of each wave is always relatively easy and low volume and that provides a permanent point of recovery. The jump from 12s to 10s to 8s, etc. is a linear organization scheme that gets the lifter into strength-specific territory faster. I really like this as a Base progression. It can be done in lower rep thresholds, but I've had devastating results with it in the 8-12 range. I literally had a client quit on me because he was disturbed by the stretch marks from the rapid muscle growth. I would recommend using it specifically to grow (high calories, plenty of rest) then switching to a strengthspecific 'intensifying' approach as part of a Peak phase to chase new PRs. LINEAR PERIODIZATION / INTENSIFYING Linear periodization will start the program with repeating sets of high reps at a lower percentage, say 5x10 at 60%. The weight goes up every week as the number of sets and reps drops, until the whole thing finishes with one set at a new one-rep max. WK % 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 5x10 4x10 4x8 4x6 3x6 3x5 3x4 3x3 3x2 2x2 65 70 74 78 80 82 85 88 91 94 11 2x1 97 12 1x1 100 This pattern is also called 'classical periodization'. It features a smooth, uninterrupted increase in weight that is more about looking nice on paper than optimizing results. Most iterations of linear periodization modify away from the 'smoothness' to better allow recovery over the entire run; some include deload weeks every 4th week or so while others progress in a wave pattern. Any method that drops volume as the weight goes up can be referred to as 'intensifying', as the reduction in sets allows the most amount of weight to be handled. This is the optimal strength-specific approach for progressive programs. I like abbreviated methods of intensifying that occur over a few weeks instead of an entire 12+ week cycle. If I had success in a volumizing program during a Base phase and wanted to intensify as part of a Peak phase, I might follow something like this. Week 1 5x5 @ 80% Week 2 3x5 @ 85% Week 3 Max 5 If I was in no particular hurry, I could repeat that by aiming to add 5-10lbs each cycle for several cycles. On the other hand, if I had a deadline for a meet or a 1 rep max test, I could instead push forward linearly into 3s, 2s and 1s. Week 4 5x3 @ 85% Week 5 3x3 @ 90% Week 6 Max 3 etc...... BLOCK PERIODIZATION Block periodization takes a loosely linear model and breaks it into Individual chunks of training, 4 to 6 weeks long. Instead of a mindlessly smooth increase, each individual block worries about adapting to one specific quality. The volume might go up and down within a particular block and the change from one block into the next is usually more jarring. Block 1 65-75% Wk 1 3x8 Wk 2 3x8 Wk 3 4x6 Wk 4 4x6 Block 2 75-85% Wk 5 5x5 Wk 6 5x5 Wk 7 6x4 Wk 8 6x4 These are all examples of progressive programs where the method of progressive overload is obvious. These programs follow a pattern that commits the lifter to making specified jumps at specific points of the training. They are extremely popular and for good reason: they work predictably well for novice and intermediate lifters and they are super simple to follow. One of the pitfalls of a progressive method is that it moves things forward on a set timeline and that becomes harder to implement with stronger lifters. For example, if you are slated to repeat your deadlift workout each week with a predetermined increase of weight, you need to have A.) gotten stronger at the rate the program anticipates and B.) be refreshed enough from the previous week's work to display that strength. The time needed to recover and display an increase in strength changes over a training career and the rate of change is different for each lifter and each lift. There are a lot of ways to modify progressive programs as you get stronger:. • A good progression based program won't assume substantial increases in strength somewhere in the middle of the program; it will feature percentages that are manageable for the entire macrocycle OR use some method of auto-regulation (like RPE) that molds the work to how the lifter is currently performing. • As lifters advance, they can place similar workouts further apart. A deadlift progression, for instance, might go on a 9 day split instead of 7 OR alternate every week with another lower body movement to keep the rate of progression sustainable. • Advanced lifters might also find that they can't train all movements with the same level of attention. A progression based program might program a block to give attention to the squat while reducing effort with deadlifts or replacing them with lighter variations. I feel that progression-based programs solve more problems than they cause for novices and most intermediates, so they remain my preferred method of programming. As you get comfortable with them, you will have a better intuitive sense of your own tolerance for work and will be able to transition to a static program more easily. Base Strength outlines a long list of progressions that follow 3-week waves. I like the 3 week wave by default because it typically corresponds to a low, medium and high stress week which casts a wide umbrella over novice and intermediate lifters. Some rely on percentages of a one rep max, others on rate of perceived exertion, but the entire list features enough variety that just about anyone can find a sustainable progression for any lift. STATIC PROGRAMS Static programs are what I call the ones that don't have a clear cut or predetermined method of progression between each session. The progressions are either hidden in the complex mathematics of subtle volume and intensity changes or it comes organically after the lifter has adapted to a period of training. Olympic lifting programs are a common example of hidden mathematical progression. Most of our inspiration for programming comes from Soviet-era data which obsessed over lifting metrics like tonnage and number of lifts. If you look through any two workouts in most Olympic programs, it's almost impossible to see what meaningful changes occurred from one to the other; the changes in weights, sets and reps might as well be static on a television set. Instead, you have to pick apart the individual metrics and see how they change over the entire cycle. For instance, one block of training might keep a lifter working tightly in the 7080% range and the main change as the block goes on is that the ratio of work done at 80% is higher at the start than the beginning. This won't be obvious until you see it on a chart. Boris Sheiko, arguably the most decorated powerlifting coach in the sport, was a Russian Olympic lifting coach first and takes much of his inspiration from that style of training. If you were to look over his programs, you might see that the heaviest squat in week 1 is 85% for 2. At week 4, the heaviest attempt might still be 85% for 2. If your history is with progressive based programs, you will be confused. Each exercise works up over several sets to a 'top weight' (85% in this example) and usually works back down; the main driver of progress session to session will be changes over weeks to how many sets are done with each weight along the pyramid. The loads are all sub-maximal, which makes it easier for volume to be manipulated. Instead of just pushing more weight, more weight, more weight, entire blocks of training keep the lifter adapting to one specific performance threshold. During that time volume goes up to create stress or down to permit recovery. Once this threshold is adapted to, they advance into the next block where the same method is used in a more competition-specific threshold. The Soviet methods generally reject the smooth linearity of 'classical periodization' and, instead, lean on templates that roll the volume and intensity back and forth each session at will. Methods like decoupling volume and intensity were effective at balancing stress and recovery in elite lifters but are extremely difficult to get a handle on. I don't recommend such an approach unless you have a seasoned veteran to hold your hand along the way. Westside-inspired programs feature weekly one-rep maxes as the backbone of the program and rotate exercises each week to allow recovery. It certainly isn't as skill-based as Olympic based programs are, since attempts are always at limit and the movements rarely stay the same. However, the lack of a preplanned rate of progression qualifies this approach as a static method. A graph of Westside-style periodization shows a flat line for volume and intensity; sets, reps and percentages always stay in the same range. The best example of a static program that is better suited for the average trainee are the ones put together by Mike Tuscherer via his Emergent Training Strategies. Mike talks about starting with a new trainee by setting a weekly split (which is based on his best guess of what they will benefit from) and having them repeat the same work at the same RPE for several weeks. The idea is that each workout will cause a training stress that should lead to some growth. If they've gotten stronger the next week, the same RPE will be executed with more weight. If they haven't or are under-recovered, they may use the same or less weight. He repeats this until he finds a 'peak event', which is the last week that featured a good result before performance backslides (generally 4 to 6 weeks). This is elegant for a few reasons. One is it shows that you can continue growth short term without having to jack up the stress each session. If a certain number of sets and reps at a given weight causes growth the first time, diminished returns start to show but it doesn't stop giving results the very next workout. This fact makes meandering programs like Sheiko's seem less mysterious; you can take several weeks to adapt to a particular threshold without worrying about dramatic, forward bumps in effort and rely on the shock of the next block to disrupt homeostasis once again. Another point of beauty is that it bases the specific time frame for adaptation around the individual lifter. The pacing of less developed lifters features a lot of play in the joints but it is absolutely crucial to know these time frames when you are programming for advanced lifters. From the data collected from this method, you can plan block changes around when the lifter is likely to stall or accurately schedule peaks for a meet. Then there's the big point of elegance: rate of perceived exertion. Mike T. sidesteps the big question mark of sustainability by never prescribing an arbitrary weight and hoping it suits the lifter's needs for that day. Instead, weights are always based on how the lifter feels. An RPE 7 is always an RPE 7 and you can find that any day, regardless of whether it is more or less weight than last time. It ingrains sustainability into the fabric of the program and saves workouts that are too-often scrapped because a prescribed top set wasn't hit. This inspired me to ditch the progressions for my off-season this year and try a more instinctive static approach until I have to plan an actual contest peak. As it stands right now, I'm training each lift twice in a 9-10 day 'week' by fitting the following work into a MWFS split. This makes 4 full microcycles last 6 weeks. I'm alternating between a low rep (5x1) and high rep (5x5) day and following each main movement with a few variations and a ton of accessory work. I have zero plan for progressing week to week, I just keep the work in the same threshold and let how I feel that day determine the weight (I usually bias away from maximal efforts anyways). DAY 1 DAY 2 DAY 3 Deadlift 5x1 @ 7 13" DL Top 3 @ 7 Accessories Push Press 5x5 @ 7 Log Strict Press 3x5 @ 8 Accessories Farmers 2x50' @ 7 Bag Carry 2 x 200' Bag Toss 8x2 Axle Clean 5x3 @ 6 DAY 1 DAY 2 DAY 3 Deadlift 5x5 @ 7 Box Squat 3x5 @ 7 Accessories Push Press 5x1 @ 7 Pin Press 5x3 @ 8 Accessories Yoke 3x50' @ 7 Stones 2x5 @ 8 Log Clean 4x5 @ 6 H-Stone Carry 2 x 200' The point of this was to prevent me from over-thinking during the off-season and just get some really good work in before planning a prep (which will be a progressive-style program). I haven't added a single bit of excess stress by going heavier than the RPE recommendation or by increasing the number of sets. In fact, I wrote this on the wall in the gym as my only reference: by not to writing down my working weights for each week, I was forced to pick weights according to my current stress level. So far, the result has been astounding. Recovery issues that have plagued me on deadlifts aren't a problem and I'm pulling with more frequency than ever before. Planning weights for later movements has been easy as well, since it's hard to predict a progression for the third lift when you're gassed from progressing the first and second. I just transitioned into the second block and made small adjustments to the rep schemes and movement variations to keep progress moving. I'm not just writing this to shill Mike T. as a coach and writer, I'm hoping it connects some dots for you later on when you are obsessing about the exact rep goal you should have on the 4th exercise of your 3rd workout. In the face of consistent, frequent work, it doesn't matter that much. PACING EFFORTS AND RECOVERY When I first started competing in strongman, I found myself talking to one of the better lightweights. The guy was a Pro who pulled 750 at 231lbs and ran a training crew with a few other 700+ pullers. "You guys must deadlift all the time!" I exclaimed as I looked for a rationalization for their freakish performances. He laughed and said "We only pull twice per month". At 19, I still had the 'harder than yesterday' mentality stuck in my head and thought that getting to the top was really as simple as just keeping my foot on the gas. Shocked as I was that less could be more, that was 15 years ago and I've only had that information affirmed by the elite lifters I've talked to since. I'll repeat something about pacing recovery from before that you might have glossed over: as lifters become more developed, hard efforts with the main movements have to get placed further apart with other workouts made up of different movements, different thresholds or reduced efforts being placed in between. These guys and all of the other monster pullers don't just pull every 14 days and sit on their heels eating Ho-Hos the rest of the time. They are doing other modes of training that create a useful stress while still allowing systemic recovery. That is the key to balancing stress and recovery in an advanced program. For these lifters, it was weekly work strongman events that absolutely decimate the posterior chain. For some powerlifters, it's variations like box squats and good mornings along with speed or recovery work to prop up weekly volume and reinforce technique. For others, it's incorporating a slightly different movement that provides a different neurological stress and avoids hitting the exact same structures the exact same way (remember, variety is a form of recovery). Here's a run down of the big things that hinder recovery: • MAXIMAL LOADS We often use the term 'CNS' (central nervous system) to talk about the major systemic effect of fatigue from high efforts. The brain sends signals along the nervous system to recruit motor units and the idea is that the CNS fatigues the most when the biggest muscles are being used to recruit the greatest number of motor units. Where continued training with high effort is synonymous with growth, we notice a backslide in progress when efforts close to 100% of a 1 rep max are done with the same movements on a weekly basis. There's a bit of controversy around the role of the CNS here and I'm not going to get into that. I just know that the model seems to work in practice so I'm going to stick with it. • MAXIMAL EFFORTS Heavy weight causes a ton of instantaneous motor recruitment, potentially 'frying the CNS' in the process. Well, the same logic holds up when you consider the effect that soul-sucking AMRAP sets have on forcing high threshold motor recruitment. Add on to that the extra tissue breakdown and extreme substrate deficit experienced over the whole body and you can see how something like deadlifts done for one set at very high effort would have a greater recovery cost than repeating sets at a lower RPE. • EXTREME VOLUME If the amount of work you do in a single session is substantially higher than what you are accustomed to, it's possible that it can set you back for your next workout. Now, the point of training (especially Base phases) is to adapt to greater amounts of volume than you are used to but this is a process that should be done slowly and deliberately. Don't double the number of working sets you do all at once and be surprised when you are dragging through your next workout. The kicker is that all of these variables (load, effort and volume) represent things that we need to include in training in some capacity to grow. Instead of avoiding them altogether, we can keep them from turning on us by understanding and applying a few strategic methods. DELOADS Deloads are an informal fixture in the field of sports performance; they are routinely talked about by experts in the field but I haven't seen them defined in any text-book I've read. A deload is an intentional break from volume and/or intensity specifically for recovery purposes but you will find that there aren't many hard lines in the sand as to when and how much. The most common approach is to schedule them after 3 weeks of training like clock-work but this casts an unnecessarily wide net; most trainees simply won't have earned it and will be discarding a week of training they probably could have used. In the earlier days of powerlifting, the deload served to give more advanced lifters time to recover from the very heavy attempt they would do week in week out. Nowadays, it's used as a generic prescription even though most programs control for load and effort. I recommend using deloads as a tool only if your have been using high percentages at high RPEs for multiple weeks in a row. If it's your third week of doubles at 95% and you are getting beat down, then yes, take a week and clear out before resuming. But if you are on any of the numerous programs that keep the weight sub-maximal and change volume and intensity every week to account for recovery, you probably don't need it. WAVE CYCLES Cycling progressions are extremely common in the world of strength e-books and I'm a huge fan of them myself. They're a next step up from simple linear progressions that just add 5lbs each workout and that makes them appropriate for intermediates who need more recovery. They basically arrange the rate of progression so that the work goes from easy to hard or from lighter to heavier over a period of weeks before restarting and building back up; basically linear progression with extra steps. The lifter gets to work up to the hardest/heaviest effort over a short period of time then recovers the very next week when the cycle starts back over. 5/3/1 is the most well known example. Week 1 5x3 80% Week 2 3x3 85% Week 3 1x3 90% Week 4...... 5x3 80% + 5lbs REDUCED OR VARIED EFFORTS Progressive programs can set one workout as the main progression that drives stress and alternate that between lighter or varied work. There are a few different timelines you can schedule these variations. Programs like the Texas Method or Heavy/Light/Medium do this on a daily time frame by working each lift 3 times per week and varying the percentages and volume change for each workout. The weight goes up every week by a small amount but the work in between the heaviest workout allows recovery by using the same reps for less weight and fewer sets. Monday 5x5 75% Wednesday 2x5 70% Friday 1x5 80% Monday.... repeat +5lbs Alternating programs are common for advanced lifters. If, for example, a deadlift is done heavy on Wednesday, the following Wednesday would feature speed work or work at a substantially reduced percentages so that the heaviest weight could be handled again the Wednesday after that. The light work allows volume and technical practice to stay reasonable throughout the month while the hard efforts get pushed every 2 weeks without digging a recovery hole. Week 1 Deadlift 80% x 3 Week 2 Speed Pull 60% x 10x2 Week 3 repeat +5lbs DUP programs (daily undulating periodization) work different training thresholds throughout the week. Day 1 might be 3s, Day 2 sets of 6 and Day 3 sets of 10. This still represents a substantial amount of work but each varied effort taxes the body in a slightly different way, giving some amount of recovery to the specific structures and motor patterns that were taxed on the heaviest day. This looks like the Texas Method and H/L/M but notice that those programs focus on changing the effort where typical DUP changes the rep threshold. Day 1 Squat 65% x 3x8 Day 2 Squat 75% x 5x5 Day 3 Squat 85% x 1x3 NEXT WEEK repeat +5lbs *** The "repeat +5lbs" was just a lazy place holder for "some stress increase". There are many patterns and methods to do that, so don't think 'the 5lb jump' is the gold standard for progressive overload.*** DIFFERENT MOVEMENTS Westside is most well known for using changes in movements to afford recovery. The system was organized around a desire to train maximally week in and week out and maximal training can't be done with the same movement every week unless a deload is taken. What was observed is that small movement changes modified the stimulus just enough to avoid backsliding while still having some positive effect on the main lift. This fits the CNS model to explain why recovery happens when using different movements; the main thing being controlled for here is the specific neurological pattern of motor recruitment. Critiques aside, this does exactly what it is supposed to do and can be used strategically to prevent stagnation. Week 1 Max 1 Bench Press Week 2 Max 1 Board Press Week 3 Max 1 Pause Bench Week 4 Max 1 Close Grip Bench Another example is a static approach that organize in a block-type structure. If a lifter wants to train in a similar threshold for a certain period of time, they can train the same for several weeks and then change to a different block. The sets, reps and effort might be the same but a change in main movements and variations serves as a type of reset. (new block) Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Top 3 Top 3 Top 3 Top 3 RPE 7 RPE 7 RPE 7 RPE 7 Wide Squat Wide Squat Wide Squat Pause Squat SUB-MAXIMAL WORK This has become my preferred approach as I've gotten older and was absolutely integral to the all-time PRs I set in my mid-30s. If you make a habit of keeping reps in the tank for each set of your training block, it becomes very hard to dig a recovery hole that impacts the rest of the week. Yes, working AMRAPs to the limit or moving heavy weight around 100% can be extremely effective for driving growth and, yes, committing to sub-max work means missing out on that. But the problem with those approaches is figuring out 'what's next' and that is a question to answer when recovery and stress have to walk a tight rope. It goes a long way to taking the guess work out of training when getting enough work in doesn't require going Super Saiyan but is just a matter of hanging around and doing enough sets. Most soviet inspired programs live by this approach and the most successful powerlifting specialization programs do as well. Pavel Tsatsouline boiled down decades of research by the Soviet system into a few actionable points: only half of your workouts should be very substantial and working sets should only feature 2/3 of your rep limit at that weight (6 rep max used for sets of 4, for instance). Broad advice, yes, but it fits nicely with what we've outlined so far. LINEAR PERIODIZATION The hallmark of linear periodization is to drop volume over time to allow recovery for the increasingly heavy loads. This is a little more nuanced, however, as a successful run at a linearly periodized program still requires maintaining recovery through each individual part of it. If you run your 10s too hard in the beginning, you will have trouble meeting your prescribed jumps for 8s, 6s and so on. The program will still need to keep work sub-maximal, include deloads or be comprised of individual blocks of training that wave the effort and load. LONGER TIMELINES One of the best changes I made in my training was taking my work week out from 7 days to 9-10. It sounds like I'm giving up valuable training by taking longer to do the same but the fact that I'm systemically recovered each workout has allowed me to work at a consistently higher threshold than I've been able to for years. If the nuances of trying to find a perfect cycling program stress you out, you can make it easy on yourself by incorporating just a little more rest. RECOVERABILITY FOR NOVICES, INTERMEDIATES AND ADVANCED This is where the discussion of pacing recovery gets legs, since the need for recovery changes over time. • High Frequency/High Effort Novices have an extremely difficult time over-training and seem to bounce back from everything they do. This is how simple linear progression programs (+5lbs every few days) become so universally productive; they exploit the fact that novices can recover quick from hard efforts and can guarantee continued increases in weight multiple times per week for long periods of time. I think of novices as being 'too weak to work', meaning that their artificially low amount of mass and neurological ability doesn't allow the type of stress that requires extensive time off. This guarantees that adaptation outpaces breakdown and the novelty of training is so fresh that each workout results in new all-time highs. Now, just because novices can do high frequency and high effort workouts doesn't necessarily mean they should. Novices can actually get away with anything and, all things being equal, I prefer they practice good habits now to set the ground work for when training actually gets tricky. This really means getting most of their practice from sub-max weights and learning to drive progress by something other than going as hard as they physically can. • High Frequency w/ recovery days or Low Frequency/High Effort Intermediates don't have a choice; they have to include recovery either by keeping the frequency low enough to recover from strenuous training sessions or by making sure that most of the sessions actually fall short of strenuous. Texas Method, H/L/M or DUP area ll examples of high frequency programs that use varied or reduced efforts as recovery. Any once per week or alternating program that features a substantial amount of work followed by a week or more of rest is an example of low frequency/high effort. • High Frequency/Low Effort or Low Frequency/High Effort Advanced lifters have to commit to effort or frequency; there just isn't room for both. I'm inclined to recommend static, high frequency programs that keep the RPE down, since it is the most specialized method and allows each workout to be molded by the lifter's own recovery ability. However, there have been plenty of lifters who tweaked their once-per week split over time to keep that pattern working for them. Remember that more frequency means less work and vice versa. If an advanced lifter wants to make low frequency their bread and butter, then they have to be incorporating a lot of work on the back end to merit the long break in between days. They also need to have no question about their recovery abilities with each lift as this has to determine which pattern of progression is going to be used and how fast it ramps up. THE DIRT ROAD There are so many different discussions about the ins and outs of programming for strength that it can be overwhelming. I've spent the last few decades trying to absorb as many bits of information as I could and find ways to put them into practice. I frequently struggled with bridging the gap between the trivia found in formal studies and textbooks with the actual experience of getting in the gym and putting plates on the bar. The rote information provided a set of guidelines to follow but training instinct would always interfere, pulling me away from those guidelines and what they were supposed to do. For instance, let's say I came across a template for a block periodization scheme that prescribed the parameter of work between 70 and 80% for the first phase (accumulation). Keeping in the tradition of formal systems that spawned block periodization in the first place, the template uses Prilipen's chart to pick how many sets and reps will be done over the 4 week block. 70-80% will be optimized, according to the chart, if I use 3-6 reps in each set for 12-24 total reps. Let's assume I don't waste 8 hours fixating over the arbitrary ways I can get to 12 to 24 reps using sets of 3 to 6 reps. The program gave me the weekly split and the list of exercises and I have the appropriate percentages and amount of work for this phase. This feels like I should have everything to confidently implement the program. But, in reality, my thought process goes like this: Do I work between 70 and 80% on each workout or do I start at 70% and build up to 80%? How fast do I do that? 70% is kind of light, I think I should get to 80% the first day. How hard is each set supposed set be? These reps are kind of easy, I don't think I'm getting stronger from this. Do I do more reps or do I add weight? This is too light,, I really need more weight on the bar. I think I'll put a quarter on. If this amount of anxiety didn't cause me to give up and switch to 5/3/1 for the 19th time, I would undoubtedly end up blowing the progression by doing too much too soon and leaving no room to increase the percentage when I was supposed to. Switching to a 'heavy' phase 4 weeks into a program is meaningless if you talked yourself into going heavy on day 1. This was actually me for my early years of training when, completely unsupervised, I attempted to try my hand at more advanced methods of programming. I eventually learned my lesson and came up with way of conceptualizing each block in a way that made sense to me and prevented me from flying off the rails. The result was more compliance, better decision making and, of course, gains. It goes like this: Imagine a truck on hard asphalt that's trying to drive as far into a patch of dirt as possible. The truck has a ton of traction on the asphalt and can pick up a lot of momentum but it loses some of that traction when it hits the dirt. The truck slows as it pushes on, eventually getting to a mud pit where it stops all together. The driver manages to back up a few feet and push forward into the mud but just doesn't have the traction to build up any speed. He does this for, I don't know, a few years, spinning his wheels but still telling his truck buddies how he's one good push away from making it out of that mud pit. This should sound familiar. After an embarrassing amount of time spinning his wheels, one of the driver's more advanced truck buddies drives over and says, "For the love of.... it's been 3 years, Jeff, and you haven't gone anywhere. Like I told you the first time, back up a little bit more and maybe you could get some traction.". "Back here?", he says, pulling a few feet back into the dirt. "Nope. Further." "Back here?", Jeff said, concerned, as he rolled to the start of the dirt patch. "No, buddy. FURTHER." "What in the.... there's NO WAY I'm going to make progress from all the way back HERE!". Jeff was adamant his friend was just hazing him. There were surely some secrets to getting through the mud pit without backing up that hIS buddy was keeping from him. "Just shut up and hit the gas," the driver said. Jeff hit the gas, skeptical and kind of annoyed that he had been made to back track on all of his precious progress. He had been carving out those inches in the mud for years and was not happy to give up on them! He built up speed on the asphalt, then transitioned smoothly into the dirt patch as, to his sheer amazement, he bulldozed through that mud pit and ended up on the other side. "Well, I'll be.... why didn't you tell me that 3 years ago, bub?!" "I did, Jeff. But you were just having all kinds of fun playing in the mud." This 'dirt road' analogy is how I think of every segment of training that I'll ever do. It applies to novice linear progressions, the 3-week wave progressions, linear periodization models and static blocks, like the one I attempted using Prilipen's chart. In case you missed it: start on solid ground, build up momentum, get into the hard part, then back up and start again. Let's revisit the example block periodization template from before. The 4 weeks just requires work in that 70-80% range and doesn't specify which workouts should be done at which percent. It looks like a static program, which means I'm focused on getting comfortable in that range at whatever rate I can handle, not aggressively adding weight, sets or reps each week. I want week 1 to be kind of easy; I need to establish plenty of traction so I can carry that momentum into the following weeks. That means keeping efforts low and the workload manageable. I'm going to work through the whole range each workout and increase efforts in later weeks as it feels appropriate. If we are working the entire range of 70-80% on day 1, that means that 'easy' days will have more sets around 70% and 'hard' days will have more at 80% A trick when working in static programs to keep the RPE appropriate is to work reps that are 1/2 to 2/3 of your rep max at that weight. 70% is generally a 12 rep max, so we do 6. 75% is typically 10 rep max, so it's done for 5-6 and 80% is usually an 8 rep max, so we do 4-5. Looks like our shortcut fits pretty well with the prescriptions or Prilipen's chart. Week 1: 70% 2x6 75% x 5 80% x 4 75% x 5 = 26 reps, 1 set at 80% Week 2: 70% x 6 75% x 5 80% x 2x4 75% x 5 = Week 3: 70% x 6 80% x 2x4 75% x 5 = 19 reps, 2 sets at 80% Week 4: 75% x 5 80% x 3x4 = 17 reps, 3 sets at 80% 24 reps, 2 sets at 80% The first week is easy as pie, just getting our feet wet with the workload. The second and third increase stress and peel back some reps. The last week gets us into the weeds by featuring the most amount of reps at the highest weight. The start of the next block would jump to a higher percentage range (80-90%) and repeat the pattern. Easy to medium to hard, then reset. Asphalt to dirt to mud, then back up. FINISHING THE PEAK: CONTEST PREP "Peak phases" in this book refer to dedicated periods of training that are more specific and lower volume than generalized Base phases. They should exist in anyone's long term training plan, competitive or not, because it provides a novel shift in the training stress (which combats diminished returns from doing the same old thing) and focuses that novelty towards true strength with heightened specificity and greater recovery (SRN). "Peak" in most training discussion usually refers to a specific competition peak, where the lifter plans their last few weeks of training before a meet in a way that brings their performance up to and beyond 100%. Peak phases can be directed very nicely into a true competition peak because they have already checked many of the boxes of competition preparation, such as exercises selection being limited to the most strength-specific ones and volume having dropped to permit recovery in the face of heavy loads the lifter is new to experiencing. I mentioned it previously in this book, that fatigue accumulated from working weeks hides your true strength: if you are working hard enough to grow you will be too fatigued to demonstrate true strength. The biggest job of a competition peak is to lower fatigue to the point that true strength can be expressed. Consider a lifter preparing for their first competition. They may have been diligent with their training over the last few months, sticking to the recommended percentages and enjoying signs of progress along the way. But as the contest gets closer, anxiety kicks up. Every idle moment now involves mentally running through all of the possible game-day scenarios, from absolute domination and the status that comes with it to complete, ego-crushing failure. The result is about as predictable as any aspect of human behavior can be. With only a couple of weeks left before the meet, sessions get longer, harder and more frequent. The desire to hit those fantasy third attempts on the bench press or to set a PR on the axle deadlift for reps is now influencing last-minute decision making. With three days to go, the nervous lifter tests the contest weights once again, thinking to themselves, "I have to make sure". This lifter might soothe their anxiety with a satisfactory performance right before the show. Maybe their openers move well or they hit the rep goal they wanted in contest and they think, "all right, I'm good". Then contest day comes and the warm-ups start to drag. Bar speed is low, joints are stiff and when it's their time to go up to the platform, they get absolutely stapled. In these last weeks, there is not going to be some magic stress that bumps your strength up beyond what any previous session could. You've already done the training, already gained the conditioning and any stress that would be so significant as to force another dramatic adaptation will A.) sap your recovery and leave you dragging for the show, B.) get you injured or C.) both. The only thing you can do is to follow the plan and let your body take advantage of the extra recovery. You won't get stronger from doing more but you sure can blow your chances at a good performance. As coaches have reiterated to countless nervous athletes in the days before their biggest performances, "the hay is already in the barn". Base and Peak phases can be ran back and forth by non-competitive lifters, but this is what they look like through the lens of an actual meet prep. • Base Phase - Weeks 1-8 Similar to 'hypertrophy', 'volume' or 'accumulation phases' in other periodization systems. The rules are largely the same between all of them: broad selection of movements, varied rep ranges, lots of total volume, emphasis on building mass. Work is very often in the 70-80% range with few sets above and below. • Peak Phase - Weeks 9-12 Also called 'strength', 'transition' or 'transmutation' phase. Smaller developmental movements are swapped for more strength-specific ones. Volume drops by default with lower reps, but the total number of sets might still be high. The goal here is to steadily acclimate to loads in a heavier range in movements that are most similar to what you will do in contest day. Work is often in the 80-90% range with few sets above and below. • Contest Peak - Weeks 13-16 Also called a 'taper', we are solely focused on peeling away work to let more and more strength become realized. At this point, non-specific movements are dropped completely, leaving us with just the main lifts and perhaps one or two variations. The number of working sets are dropped a little more each week, lowering the volume by 50% or more over the course of the phase. The heaviest attempts are planned so many days out based on each lifts timeline for 100% recovery. **** The weeks listed are just an example. Prep times can differ wildly. NOVICES Novices don't need a true taper for the same reason they can get away with consistent progressions in their general training: recovery just isn't a factor. That's not to say that they should be reckless; damage can certainly still be done by doing too much too close to the meet. Preparation just doesn't require walking a tight rope. Signing up for a meet doesn't change best practices. Novices should resist the urge to ditch the novice LP they committed to for something that looks like a 'legit' powerlifting prep: it won't apply. The goal should be to continue their progression as normal and take a few weeks to include some lower rep work just to gain familiarity with the commands and get an estimate of where openers should be. This is where the designation of novice/intermediate/advanced becomes important. The label is primarily concerned with your recovery ability as you get stronger and having a handle on it will give insight into the pacing of your last heavy attempts before a meet. Novices recover faster from hard efforts, evident by the fact that so many can schedule their last heavy lifts 4-5 days out (maybe 7 for deadlifts) without ill effects. If you have been training for some time and find that this wasn't enough time, consider reevaluating your status. Monday Wednesday Friday 3 WEEKS OUT Top 3 @ 7/10 Top 3 @ 9/10 Top 2 @ 8/10 Followed by program as usual -----------------> 2 WEEKS OUT Top 2 @ 9/10 Top 1 @ 7/10 Top 1 @ 9/10 Followed by program as usual -----------------> CONTEST WEEK Top 1 @ 8/10 No extra work REST MEET This is a broad example of how a novice can squeeze in work to prepare them for their first powerlifting meet. Don't sweat the details, this is purely an example. Just pay attention to the pattern. It starts by introducing you to low reps while leaving you room to add weight each session and you steadily get your toe in the water without jumping straight to the heaviest weight you can muster. You are still building skill, awareness and confidence and you won't do that by folding yourself in half under something that's too heavy. Be faithful to the RPE scale. No wishful thinking here. Your absolute heaviest single should be about a week out and that will represent a solid second attempt at the meet. You can squeeze one more workout in a few days later to keep you moving, but effort should be conservative. Note that I don't recommend trying to hit a PR during the last workout; it's just a primer to keep you trained and mentally engaged. In fact, make sure that it's 5% or more below what your previous single was. This strategy of hitting our last hard attempt further out and then filling the time to the meet with reduced efforts is a strategy we will lean on heavily in more advanced peaks. INTERMEDIATE Intermediates will be following full prep cycles in order. By the time they get to the taper, they should already have built up a lot of experience around the 90% range and be razor sharp with their exercise variation. The total number of working sets at the end of the Peak phase should still be pretty high so fatigue will be as well. The first week of the taper should have a designated drop in volume, 10-20%. You don't have to pull out a calculator and crunch all of the numbers, just eliminate a working set from a couple of the exercises. Remember, you should still be exposing yourself to more load each week. Repeat the second week by peeling away more sets and, again, adding weight. 4 Weeks Out Monday Friday Top 3, -10% 4x3 3x4 @ 7/10 Saturday 2 Variations: 4x4 3 Weeks Out Top 2, -10% 3x2 3x3 @ 7/10 2 Variations: 3x3 2 Weeks Out Top 1, -10% 2x1 3x2 @ 7/10 1 Variation: 2x2 Contest Week 60% x 3x5 MEET This looks more complex than it is. Let's break it down. For this movement, we are creeping towards handling 100% of our 1 rep max. I don't like over-specializing in singles for intermediates; at this level of advancement, volume is still a big driver of progress and it's harder to keep it high when you are only clipping off one rep at a time. So my rationale is to work up to the heaviest 3 reps you can handle with confidence and sound execution, then bump it to 2 reps the next week then 1 rep the last week. Most of our work in this example consists of 'back-off sets', which are just repeating sets at a lighter weight. Whatever your top set was for the day, drop 10% and knock off a few sets for the same number of reps. This part is vital as it represents technical practice at low reps but also makes up the volume that will be peeled away for the taper to work in the first place. The back-off sets go from 4x3 to 3x2 to 2x1, which is a pretty dramatic drop in volume. This is an example of a 2-day per week "Heavy/Light" split where we are hitting a top set on one day and doing token volume work at reduced effort the next day. You could alternate "Max Effort/Dynamic Effort" days, "Volume/Intensity" days or even switch the movements and keep the threshold similar. There are a ton of ways, but the pattern is the same for all of them: weight steadily increases while the amount of work melts away. For intermediate and advanced lifters, the timing of your peak will revolve around one thing: how much time it takes you to recover from your absolute heaviest attempt. This is different for each lifter and for each lift, though there are some guidelines I can give you to help estimate. If you are confident you can max on a bench press and perform just as well 7 days later, than that represents where your last substantial workout will be. Your absolute heaviest bench workout might come a session or two before that but 7 days out will represent the last day that you demonstrate any substantial effort in that lift. Many lifters find that benching and squatting can be timed similarly, though squatting sometimes requires a few extra days, and an overwhelming number of lifters cite deadlifts as the lift that requires the longest. In a study of from the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, New Zealand powerlifters (average Wilks of 432) were polled for their tapering practices. The key takeaways were as follows: Total training volume was the highest around 5 weeks out and the highest % work was done about 2 weeks out. Volume was reduced by 60% or so over the taper, accessory work was dropped around 2 weeks out with the final training session being performed 3-5 days out. This chart was pulled from an excellent article regarding the study on maloneyperformance.com: Session Type Final heavy squat session Final squat session Final heavy bench press session Final bench press session Final heavy deadlift session Final deadlift session Days out from comp 8.0 ± 2.9 4.0 ± 1.8 Top set % (%1RM) 90.0 ± 5.4 66.0 ± 15.7 7.3 ± 2.7 92.2 ± 5.7 4.0 ± 1.8 10.9 ± 4.0 7.4 ± 4.1 67.3 ± 18.1 88.9 ± 6.1 72.6 ± 18.5 Take special notice that last workout and the last heaviest workout are two different things. The last squat and bench workouts were typically done 4 days before the meet at severely reduced percentage with the last reduced-effort deadlift day coming a full week before the meet. As you look forward through your program, intermediates should be planning to hit peak weights 2 weeks out and finish out their taper by bringing all of the work back. Note that their heaviest attempts were often short of an actual 1 rep max, averaging around 90% across all of the lifts. For more developed lifters, more is not always better. ADVANCED By the time a lifter is advanced, they should have a solid handle on their preferred training organization and how far apart their hardest efforts need to be placed. Those systems will be tweaked over a training lifetime to benefit the individual and can vary substantially depending on what methods they implement. The only thing to know at this point is that the truly elite need a LOT more time to peak properly. Where an intermediate might need 8 to 10 days of recovery after their hardest squat or deadlift, world record holders often put their last big attempt 3 to 4 weeks out and run the rest of their taper by dropping volume and steadily dropping intensity over the remaining weeks leading into the contest. This will still vary based on the lifter and how comfortable they are with each lift. Body weight is a big factor as elite super heavyweights tend to make up the extremes here; even though their strength-body weight ratios aren't as high as record holders in the lighter weight classes, the greater absolute loads pack a much bigger systemic stress FROM THE GROUND UP: NOVICES Now to take everything up to this point and put it into practice. For those new to lifting, the program should be simple enough to not cause confusion but include enough variety to build skills that will be needed in more advanced periods of training. There are 3 things that escape modern white belts when they find themselves in the honeymoon stage of powerlifting: how easy it is to build muscle, how devastatingly effective that is for short term strength gains and how absolutely important it is for long term success. We want to build muscle in true beginners as fast as possible but the emphasis still has to be on skill acquisition with the competitive lifts. Any good novice program should feature a lot of reps with those movements but it's important that those touches be treated as practice and not as a method of 'muscular annihilation'. Most of the novice LPs out there, like Starting Strength, start out light enough but use daily increases in weight to drive progress. Within a few months, lifters who are still relatively green will be using the heaviest weight they can handle for sets of 5, fingers crossed the whole time that they can muster 5 more lbs next week. Now, while that is a proven means for growth and I'm generally a fan, there are two irritating shortcomings that hang around like pebbles in my shoe. One is the recommendation to green lifters to use pure strain against weight to drive progress. Sure they CAN get away with it and grow, but should they? If there are form break downs early on, it typically won't get better as the weight gets heavier. This makes bad habits inevitable in certain lifters who didn't have the technique 'click' right off the bat. Technique aside, as lifters transition to intermediates and recovery from those efforts takes longer, the programming emphasis has to switch to include work that is not, in fact, the hardest workout of your life. Reliance on strain for the sake of it to drive progress is a hard habit to kick and, eventually, it has to be kicked. The second thing that is bothersome is that a brilliant opportunity to emphasize mass gain while emphasizing technical practice is missed altogether. When mass gain is the short term goal, work increases. Volume = Growth; remember that. Old-school LPs use daily weight jumps (intensity) to increase strength, but if we instead condition new lifters to ever-increasing amounts of work (volume), we can create monumental growth in muscle tissue while tempering them against fatigue and offering more of those practice touches we need so badly. I am a huge fan of step loading for removing both of those pebbles. Linear Progression Weeks 1-forever 3x6 (100) 3x6 (105) 3x6 (110) Weeks 1-3 3x6 (100) 4x6 (100) 5x6 (100) Weeks 4-6 3x6 (110) 4x6 (110) 5x6 (110) Step Loading Observe the differences between linear progressions and a waved step progression. I know, weight jumps take longer, but that's the point. By staying with the same load for several sessions, white belts get the opportunity to gain mastery over that weight before moving up. The increase in number of sets over each 3 week period adds to general fatigue and is a powerful trigger for growth but the stress is never so high as to force the lifter to compromise positioning for 5 more pounds. 3 weeks with the same weight has a funny way of building supreme confidence in heavier attempts, rather than fear and apprehension. Focusing on volume requires holding back on weight jumps and all-out efforts; after all, it's hard to do 5 sets of 10 when you lost your soul 8 reps into the first set. The discipline to adhere to such a plan is a skill in and of itself, one that most neglect to build. So many lifters will move past their newbie gains into the Valley of Intermediacy, where they will toil for years and years without growth. These lifters, even in the face of years-long plateaus will outright reject any program that doesn't permit YOLO attempts or going HAM when the mood strikes. But any novice who cuts their teeth on a step loading protocol will have absolutely zero problem transitioning to sub-maximal, volume-based workouts when they become necessary. That means you will have a flexibility in your training that will later become invaluable, so that you will be growing while others spin their wheels. There are no Base or Peak phases in novice programming. The only exception would be several weeks to practice openers before a contest, like we outlined in the last chapter. The idea is that novices should be able to train linearly for months at a time without recovery becoming an issue; we don't have to worry about manipulating variables like SRN to sustain progress because we can focus on pure progressive overload. Including a variety of rep ranges will expedite the rate of muscle growth. The main lifts should be in a lower rep range, 5-6, the variations in a higher range, 810, and the bodybuilding movements should be 10 to 15. Remember that effort should start out very low in the first two movements (RPE 5-6) so that you have room to build technique and confidence. Bodybuilding accessory stuff can be done with more effort. SPLIT Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday Squat RDL Bench BTN Press Deadlift Front Squat Press CG Bench Bodybuilding Bodybuilding Bodybuilding Bodybuilding Novice lifters can easily recover from training all of their lifts in a 7 day work week. This will look a lot like many intermediate programs, so getting comfortable with this organization now and learning how to pace recovery will be invaluable for future blocks. I like to blend upper and lower body movements as a means of increasing frequency; it gives you more touches with each movement pattern throughout the week and keeps you from getting so brutally sore in one area that it impacts the next workout. EXERCISES • Big 4 Squat, Deadlift, Bench Press, Overhead Press • Developmental Variations Front Squat, RDL, Close Grip Bench, BTN Press • Varied Bodybuilding Accessories Upper Body - Chest, Shoulders, Back, Biceps, Triceps Lower Body - Quads, Glutes, Hams, Erectors, Abs (Bracing) Remember that novice programs are oriented to overall development, not specificity. The variations chosen to pair with the Big 4 are what I consider to be the best general developmental movements. They reinforce sound movement patters, require more control and are better for higher volumes. They are less specific to the main lifts but that lends itself to more generalized development which is what we are after. After the two big compound movements, the rest of the workout consists of varied bodybuilding movements. Shoot for at least 3 of these movements on lower body days and 5 on upper body days. BABY BULLY MAIN LIFT PROGRESSION Squat / Bench / Deadlift / Strict Press Workout 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Weight 100 105 110 3x6+ 4x6+ 5x6+ 3x6+ 4x6+ 5x6+ 3x6+ 4x6+ 5x6+ This program is going to use 'plus sets' as a tool to increase stress on the first exercise and gauge progress. Many programs have used plus sets as a cornerstone, including 5/3/1, the Greyskull LP and Juggernaut. The basic idea is to get through all of your working sets at the prescribed sets and weight, then treat the last set as an AMRAP (as many reps as possible). Make sure that the plus set is clean and leaves a solid rep in the tank; as always, technical execution is priority. Don't take your deadlift sets to a place where you are resting 15 seconds in between reps and rounding your back like a constipated animal. And don't let your spotter force you through 6 extra reps by rowing the bar off your chest while benching. Taking sets right up to the point of full fatigue is a powerful growth stressor but it can't be done for every set all the time, at least not if you want to be able to predict your performances and control for recovery. The reduced effort sets at the start dial you into the movement and build some volume; by the time you perform the last set, the movement should feel greased and efficient and you should be primed for a big number. The AMRAP set also breaks the monotony of step loading, since you have an opportunity to beat your previous rep numbers for the 3 weeks that you are staying with the same weight. Choosing your starting weight takes some trial and error. For your first workout, estimate a weight that you can do 12-15 times and run through the prescribed 3x6+. Your AMRAP on set 3 will determine if you should change the weight for the rest of the block. If you could only perform 11 reps or less, drop the weight by a small margin for next week's 4x6+ and continue on. If you went over 15 reps, make a small jump instead. If you landed in between 12-15, carry on. Weight jumps come every three weeks as the program resets back to 3x6+. They should be around 5%, so make ample use of 2.5lb or 1.25lb plates if you need to. There is some room for a bigger jump if you had a really big upswing over the three week wave. If your 3rd week AMRAP with the 5x6+ cleared past the 15 rep mark, make a 10% jump instead. This is an exceptional case; don't look for reasons to throw more weight on the bar. Programs like these hinge on consistency to create success and smaller jumps are more consistent jumps. WAVE 1 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Squat 150 x 6,6,13 150 x 6,6,6,15 150 x 6,6,6,6,16 WAVE 2 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Squat 165 x 6,6,11 165 x 6,6,6,13 165 x 6,6,6,6,14 WAVE 3 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Squat 175 x 6,6,10 175 x 6,6,6,14 175 x 6,6,6,6,15 The example above shows what 3 waves worth of progressions might look like. The first week finished with an AMRAP of 13, so we stayed with that as our starting point. We were able to perform slightly better each workout, with week 3 featuring 16 reps on the last set. That cleared us for a 10% jump instead of 5%. The rest of the weeks progressed steadily and the cumulative effect is a substantial increase in strength in only 3 waves. 2ND LIFT PROGRESSION Romanian DL / BTN Press / Front Sq / Close Grip Bench Workout Weight 100 105 110 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 3x10 4x10 5x10 3x10 4x10 5x10 3x10 4x10 5x10 The second lifts of the workout are crucial developmental movements, so take them seriously. They will also follow a step loading protocol but with sets of 10 and no AMRAP set. You will find that repeating sets of higher reps builds fatigue much faster than low-rep sets, so an all-out set at the end isn't warranted. In fact, just treat this like homework. All of these movements require complete control and a deliberate tempo, so don't allow yourself to get sloppy. Be conservative with weight selection. As an easy guideline for weight selection, take 20% of your working weight from the main lift. If your deadlift was at 155, your RDLs can start at 125. If your strict press was at 75, your behind-the-neck press can start at 60. You won't have these numbers your first week; that's fine. Use something that is very, very easy as a way of easing into the workload and implement the weight change in week 2. Remember that the further back you start, the more momentum you can build up. ACCESSORY MOVEMENTS The key difference with this template relative to other novice programs is that it doesn't limit us to just a few movements done over a very narrow rep range. For any individual to optimize muscle growth, the aim should be to hit as many muscle fibers as possible by working different movement patterns through different fatigue thresholds. That's bodybuilding 101 and, for periods of training designated to building mass and establishing a wide base, strength athletes aren't going to do better than that. The fact is, to be a good lifter you need to eventually get comfortable in disadvantaged positions, work through different motor patterns and develop individual muscles that tend to lag behind if ignored. If you're smart, you'll do that now. The rep protocols for smaller exercises don't need to be obsessed over. These can be taken closer to failure, just keep them within the prescribed rep range. We can keep stagnation at bay by swapping them out every 6 weeks for another run of isolation exercises and restarting the process Here's an example run of accessory movements: Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday Squat RDL Bench BTN Press Deadlift Front Squat Press CG Bench Leg Press Hamstring Curl 90/90 Breathing Planks T-Bar Row Lat Pulldown Skull Crusher Hammer Curl Back Extension Lunge 90/90 Breathing Side Plank DB Row Dips Hammer Curl DB Curl All of the accessory movements can be kept at 3-4 sets of 10-15 reps. Body weight movements can use assistance or resistance as needed to keep it in this range. Start easy and add weight incrementally. Protocols for the bracing work is found under the GPP section. FROM THE GROUND UP: INTERMEDIATES BULLMASTIFF - BASE PHASE The Base intermediate program uses all 4 big movements follows them up with a developmental variation for the opposite movement and then general bodybuilding work. At this point, the variations and the smaller bodybuilding movements should aim to make lagging areas a priority; don't dedicate time to your third pectoral isolation exercise if that's not the limiting factor in your bench. VARIATION EXERCISES Developmental Bench Press Variations Spoto, Pause, Tempo, Close Grip, Buffalo Bar, Wide Grip, Feet Up Developmental Squat Variations Front Squat, Long Pause, Alternate Stance, Tempo, SSB Bar, Low Box Developmental Deadlift Variations Romanian Deadlift, Snatch Grip, Stiff Leg, Tempo, Stiff Bar/Axle Bar, Sumo Developmental Overhead Variations BTN Press, Wide Grip, From Low Pin, Seated Military, Tempo Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday Squat Dev. DL Back Hams/Quads Abs Bench Dev. Overhead Triceps Biceps R. Delts/Rot. Cuff Deadlift Dev. Squat Back Hams/Quads Abs Press Dev. Bench Triceps Biceps R. Delts/Rot. Cuff BASE MAIN PROGRESSION - SQ, BP, DL, OHP WAVE 1 65% x 4x6+ 4x6+ 4x6+ WAVE 2 70% x 5x5+ 5x5+ 5x5+ WAVE 3 75% x 6x4+ 6x4+ 6x4+ Bullmastiff operates off of a 3 week wave structure, meaning stress increases each session over a 3 week period before dropping back and building back up. Remember the 'dirt road' analogy. The last set of the main exercise is performed for an AMRAP and that number is used to estimate a weight jump for the following week. This is a method of auto-regulation made famous by Doug Young. To determine your weight jumps each week, add 1% of your 1 rep max for every extra rep you did on the AMRAP. If you are working through sets of 6 and performed 10 on the AMRAP, that is 4 extra reps so your weight jump would be 4% of your 1 rep max. If I'm operating off of a 1 rep max of 400lbs, that's 16lbs (we can safely round down to 15). Using this auto-regulation tactic, here's how that might play out in real life with a 400lb squatter. WAVE 1 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Squat 260 x 6,6,6,12 285 x 6,6,6,11 305 x 6,6,6,8 WAVE 2 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Squat 280 x 5,5,5,5,12 305 x 5,5,5,5,10 320 x 5,5,5,5,7 WAVE 3 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Squat 300 x 4,4,4,4,4,11 325 x 4,4,4,4,4,7 335 x 4,4,4,4,4,6 **** Note that the AMRAP on the third week doesn't dictate the weight in week 4; it defaults back to the percentage established above. Compared to the novice program, the progression change here hits on multiple fronts: • Going from step-loading, which is entirely sub-maximal and volume based, to a program that features an all-out set at the end of each workout represents a major shift in the type of stress. This is a kick in the pants to diminished returns, which prevents the same method of progression from working forever. You will be sensitive to the failure sets and you will grow like you were new all-over again. Think of it like a type of re-virgination. • The weights now increase week to week, making intensity a driving force of progress. This is a new stimulus as well but also one that is more strength-specific than the step loading. You've done the work to build a base, now we can start to reap the benefits of specialization. • The training program now has a deadline, meaning you aren't just running it until the wheels fall off. This is your introduction to periodization, where you get to experience how changes in load and volume effect your training week to week and how those weeks combine into blocks of training. Pay attention to how your body responds and take notes; these are the things you will need to know about yourself down the road. BASE DEVELOPMENTAL VARIATION PROGRESSION WAVE 1 3x12 @ 6 RPE 4x12 @ 7 5x12 @ 8 WAVE 2 3x10 @ 6 4x10 @ 7 5x10 @ 8 WAVE 3 3x8 @ 6 4x8 @ 7 5x8 @ 8 Selecting weights for secondary movements requires some extra thought. The main movement gets more demanding as time goes on, which means you will be more fatigued each week going into your variation movements. This makes it more difficult to use linear weight jumps for the secondary movements as the means of progressive overload. You can bank on adding a certain amount of weight to your bench each week, but then adding weight to your close grip, then your dumbbell presses, then your isolation work..... you will find this approach to progressive overload akin to ice skating uphill. An easy way to get around that is to not worry about jacking the weight up on variation movements week to week. Instead, you can focus on how much total work you do in a workout (what I refer to as 'volumizing') which is done by adding a set each week to the same weight and rep scheme. Many don't like using volume as a tool for progression because, well, it's hard damn work, (save your 'reps over 5 is cardio' memes for you Class 4 Powerlifting buddies). Sure, a lot of sets across can make your eyes glaze over at times, but I find it to be way more sustainable than trying to maintain the aggression required to pull out weight jumps across every single exercise week to week. Many of you newbies might be under the impression that going Super Saiyan 5 on every set is the key to long term growth but that just isn't a thing. As stress continues to increase over an entire phase, you will be tired. You will get disillusioned. You will have fluctuations in neurological and hormonal activity that sidelines the aggression you typically rely on for big attempts. And yet you will still be responsible for doing something that improves upon last week's efforts. Don't fall into the 'punish and pray' trap where your workout plan hinges on a prayer that your weekly increases in strength will be enough to keep adding weight onto the bar indefinitely. Save your aggression for the main lift and use the secondary movements as homework. Rules for volumizing are as follows: • Start with a weight that puts you around a 6/10 effort for ALL sets and reps, that's something that easily leaves 4 reps in the tank. If fatigue from set to set causes that to go to a 7 or 8/10, don't be a hero: drop the weight accordingly or you won't last through the program. The percentages I provide are a good starting point, but it's ok if you don't have a max to go off of and want to pick your weights based on feel. You'll have to learn to accurately estimate your abilities set to set eventually, so might as well start now. • Add one working set the following week and keep the same reps. That might seem like an underwhelming method of progression, but the point here is to schedule something sustainable that you can follow for weeks on end. Be concerned about the strain you will be experiencing in week 7, not week 2. • Weight increases are allowed but ONLY if it keeps you at the prescribed difficulty. A grindy or missed rep from an overeager attempt will require dropping the weight back at some point or else you will have no options for moving forward that don't outright abandon this pattern of progression. The sooner you advance weight, the sooner you will have to reset. We aren't here to wing it, we want to keep things moving forward on schedule, so silence your ego and be objective. Here's an example for our 400lb squatter. He hasn't front squatted in some time, so he bases his numbers off of a conservative 315lb max. Not being used to sets of 12, especially with this exercise, he starts even more conservatively at 50% and resolves to tweak the numbers as needed based on the difficulty of each set. WAVE 1 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Squat - - - Front Squat 3x12 @ 155 4x12 @ 155 5x12 @ 155 Week 1 sucked. The first set moved extremely fast and with little effort, but each set was exponentially harder than the one before. 12s were a different ball game. The last set featured burning quads, cramping abdominals and crippling fatigue in the mid-back. That was nothing when compared to the sharp pain in the lungs that worsened with each breath and lingered long after the set was over; think of suicide drills in the snow. Thank goodness for conservative weight selection. After finishing the squats in week 2, the thought of repeating last weeks effort made for sweaty palms and nervous pacing. After a 10 minute argument with himself to skip the squat variant altogether, our squatter resolved to get it done. "You don't have to break yourself, just get the work done". Shockingly enough, each set flew with minimal fatigue. He could not believe how quickly he had adapted. Week 3, he kicked around the idea of making a weight jump, but decided against it. Week 4 would feature a lower rep range, which seemed to be a better opportunity to increase load. "Just get the volume in and be done with 12s forever!" The 5x12 went easier than 3x12 week 1 and this led to a bump in confidence and excitement for the waves to follow. On to something big for next week! WAVE 2 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Squat - - - Front Squat 3x10 @ 175 4x10 @ 175 5x10 @ 185 The amraps on the main squat set were starting to get much more draining. Instead of making an overeager jump and hitting the brick wall in the front squats early, our squatter resolved to stay conservative. The 10s at 175lbs went smooth weeks 4 and 5 and represented more weight and total work in this exercise than he had done in quite a long time. Knowing that the volume would drop substantially in week 7, he thought, "what the hell, I'll work a little harder this week". He bumped week 6 to 185lb and ran through all 5 sets without incident. WAVE 3 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Squat - - - Front Squat 3x8 @ 205 4x8 @ 215 5x8 @ 225 This was the last wave of the Base Phase, meaning that a period of recovery was on the horizon. This is where we leave it all on the table. Week 7 was a nice recovery period from the week before which allowed a small weight bump into week 8. The difficulty still never climbed over 8/10. It was decided that the last week of the entire phase would be a barn burner, so he went for it, piling on 225 and committing to finishing all 5 sets of 8. The last set went up with 2-3 left in the tank and he grinned, remembering that he couldn't hit a single set of 8 at the start of the phase, let alone 5 easy sets of it. BASE BODYBUILDING ACCESSORY PROGRESSION The progression of other accessories (machines, dumbbells, unilateral work, isolation, etc.) is much the same as with the variation of the main barbell lift. We are going to volumize, again adding a set to each workout over the course of a way. We don't have to worry too much about walking the line of fatigue with these movements since they come later in the workout. Pushing the last few sets of leg extensions or tricep pushdowns can create a huge push for new growth and doesn't lead to the type of systemic fatigue that might hinder performance the following week. But remember, we are prioritizing volume as the yardstick for measuring progressive overload and that's accomplished most easily when weight and reps stay similar week to week. WAVE 1 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Squat - - - Front Squat - - - Split Squat 95 x 2x12 95 x 3x12 95 x 4x12 Leg Extension 100 x 2x15 100 x 3x15 100 x 4x15 I generally start the compound and isolation accessory at 2 sets, building up to 3 and 4 over the first wave. This is a personal preference, since the shock of the repeating high rep sets on the main movement and variation often wipe me out early on. Your goal is to steadily adapt to the demands of the training over many weeks, not to begin a phase by biting off more than you can chew. When the reps drop a bit in waves 2 and 3 and I'm more conditioned to the work, I'll reset the wave with 3 sets on the accessory and build up to 5, sometimes even higher on smaller isolation movements. Remember that it's the increases in work relative to what you are used to that forces new growth, not the adherence to an arbitrary number of sets and reps. WAVE 2 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Squat - - - Front Squat - - - Split Squat 115 x 3x8 115 x 4x8 115 x 5x8 Leg Extension 120 x 4x12 120 x 5x12 120 x 6x12 (ouch) This might be a lot more work than you are used to. That's a good thing; more work is necessary to continue past the intermediate stage. At the most, we are talking about 6 working sets on the main movement, 5 on the variation and 4-6 on a handful of smaller movements (though most weeks have much less). This is not an exceptional amount of work for a competitive lifter and it's a very small amount of work for most bodybuilders and physique competitors. If your percentages are on point and you are honest with how you evaluate RPE, the only reason you couldn't recover from this is if you are starved for food or sleep. There are programs that will attempt to work around those circumstances, but this isn't one of them. If you do take your role as a competitor seriously and mold yourself to this structure, the end result will be a base so wide you can park an air craft carrier on it. BULLMASTIFF - PEAK PHASE Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday Squat Bench Deadlift Overhead Targeted DL Dev. Squat Targeted Overhead Dev. Bench Targeted Squat Targeted Bench Dev. DL Dev. Overhead Back Triceps R. Delt/Rot. Cuff Back Triceps R. Delt/Rot. Cuff The Peak phase cuts away much of the smaller bodybuilding movements in exchange for targeted movement variations. These are movements that provide more exposure to heavy weights or specifically work areas that the individual lifter is struggling with. Targeted Bench Press Variations Board/Pin Press, Floor Press, Pause at Stick Point, Bands/Chains Targeted Squat Variations Box Squat, Pin Squat from the Bottom, Short Pause, Bands/Chains Targeted Deadlift Variations Bar at Stick Point, Pause at Stick Point, Bands/Chains Targeted Overhead Variations Pin Press at Stick Point, Pause at Stick Point, Bands/Chains PEAK MAIN PROGRESSION Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 WAVE 1 5x3+ @ 80% 3x3+ 1x3+ WAVE 2 5x2+ @ 85% 3x2+ 1x2+ WAVE 3 5x1+ @ 90% 3x1+ 1x1+ TEST/MEET Deload Test Reps are lower here and percentages will be consistently closer to 90%. The auto-regulation method still determines our weight jumps going into every 2nd and 3rd week but resetting back to the reduced percentages at the beginning of each wave is important to keep this sustainable. More developed intermediates might find that handling the heavy percentages with 4 movements each week presents a challenge. A technique that flirts with 'advanced' territory is to move the 4 workouts beyond a 7 day week. This is the default move in the advanced template that comes after this one. Below is a 3 day per week example; it can easily be turned into 4 days per week by fixing a GPP day to every Saturday. 3 Days per Week Monday DAY 1 Wednesday DAY 2 Monday DAY 4 Wednesday REPEAT Friday DAY 3 PEAK VARIATION PROGRESSION (TARGETED AND DEVELOPMENTAL) Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 WAVE 1 4x6 @ 6 RPE 3x6 @ 7 2x6 @ 8 WAVE 2 4x5 @ 6 3x5 @ 7 2x5 @ 8 WAVE 3 4x4 @ 6 3x4 @ 7 2x4 @ 8 All of the variation movements will have to intensify along with the main lifts. You won't have an established one rep max for most of them so it's best to gauge appropriate working weights according to RPE. ACCESSORY WORK So much effort will be given to the main lifts and their variations that we will only keep in a few vital accessory movements. The upper back, triceps, rear delts and rotator cuff are the most important here and they can be kept up to standard with one exercise done for 3-5 sets of 8-12 reps. There isn't a need to wave the progression in any complex manner, just keep the reps in that range and keep the effort high. You can use the advanced fatigue techniques outlined later in the book if things start to stagnate. Wave 3 of the Peak phase should only feature the main lifts and variations; drop all of the accessory movements at this point. FROM THE GROUND UP: ADVANCED Advanced lifters need to pay special attention to sustainability, both in the weekly arrangement of exercises and the rate of increase with our chosen progressions. Progressing 4 lifts forward inside of 7 days is guaranteed to be overkill for anyone on the elite side of the spectrum. I don't recommend it. The easiest workaround to making this split more recoverable is to simply extend the working week. Plan A - 4/3 We are going to adjust the time frame a typical 'work week' falls into, so for this program a 'work week' is going to be called a 'microcycle' or 'micro' to avoid confusion with a literal 7 day week. By running 4 workouts in a 3 day per week split, 7 days in between workouts turns into 9-10. This goes a LONG way to making his program sustainable. We are doing a main lift or it's variation every 4 days or so, which prevents frequency from dropping too low. It also looks nice on paper, since a single 3microcycle long wave takes 4 weeks to get through. GPP days are always done on the last day of the 7 day week. These days are vital to keep conditioning high and add extra volume to lagging areas. Don't skip. Monday Wednesday Friday Sat. 1 Lower 1 Upper 1 Lower 2 GPP 2 Upper 2 Lower 1 Upper 1 GPP 3 Lower 2 Upper 2 Lower 1 GPP 4 Upper 1 Lower 2 Upper 2 GPP Plan B - 6/4 I have had a ton of success with this split. It's more complex but allows more opportunity for non-specific work without interfering with the important stuff. As a strongman competitor, I needed a lot more time training event implements but couldn't do them effectively in a full barbell workout. By following a split of Upper/Lower/Event/Upper/Lower/Event in a 4 day per week cycle, I was able to effectively fit much more meaningful training into each block than I could have in a single week or alternating split. Swap the strongman event day with run-of-the-mill GPP work (they aren't that different) and you have a powerlifting-specific split. The 6/4 puts hard efforts with each lift far enough away that recovery can take place while keeping frequency high enough to prevent de-training. The effort I was able to put into some of the posterior-dominant events also carried over hugely to my deadlift. I only recommend this split if you are the type of person who can take this secondary work seriously. If you are going to skip most of the GPP workouts (and you call yourself advanced!), stick to plan A. Monday Wednesday Friday Saturday 1 Lower 1 Upper 1 GPP Lower 2 2 Upper 2 GPP Lower 1 Upper 1 3 GPP Lower 2 Upper 2 GPP This example shows that 2 microcycles take 3 actual weeks, so the 2 consecutive 3 microcycle waves will take 9 weeks in this split. It's important to note that this Base phase is just a primer for the Peak phase. Where non-elite lifters can benefit greatly by putting a Base phase on repeat for several months, advanced lifters need to keep sharpening the saw of specialization. These 2 waves are just planting seeds. As soon as that work is done, it's time to reap the rewards by jumping into the Peak phase. EXERCISES Instead of using general developmental variations for sheer novelty, as we might in novice and intermediate programs, advanced lifters should use secondary movements deliberately to target a specific area of the lift that needs reinforcement. For advanced lifters, each movement has to be more specialized. Front squats, RDLs, dumbbell variations, etc. won't cut the mustard as big secondary movements anymore; for there to be benefit to the main lifts at the elite level, variations have to be much closer to the competitive movements. I prefer to use pause and deficit work when volume is higher and save overload movements for when intensity starts climbing. In these templates, the Base phase variants are geared towards control at the bottom of the movement whereas the Peak phase switches those variants out for partial movements that emphasize more weight and target potential stick points. Developmental Bench Press Variations Spoto, Pause, Tempo, Close Grip, Buffalo Bar, Wide Grip, Feet Up Targeted Bench Press Variations Board/Pin Press, Floor Press, Pause at Stick Point, Bands/Chains Developmental Squat Variations Long Pause, Alternate Stance, Tempo, SSB Bar, Low Box Targeted Squat Variations Box Squat, Pin Squat from the Bottom, Short Pause, Bands/Chains Developmental Deadlift Variations Deficit, Snatch Grip, Stiff Leg, Tempo, Stiff Bar/Axle Bar, Sumo Targeted Deadlift Variations Bar at Stick Point, Pause at Stick Point, Bands/Chains Developmental Overhead Variations Wide Grip, From Low Pin, Seated Military, Tempo Targeted Overhead Variations Pin Press at Stick Point, Pause at Stick Point, Bands/Chains BIG BULLY - BASE PHASE Lower 1 Upper 1 Lower 2 Upper 2 Squat Bench Press Squat Bench Press Targeted Squat Dev DL Targeted Bench Dev. Overhead Targeted DL Dev. Squat Dev. Overhead Dev. Bench Back Hams/Quads Abs Triceps Biceps R. Delts/Rot. Cuff Back Hams/Quads Abs Triceps Biceps R. Delts/Rot. Cuff ***For a strongman competitor or anyone who wants to prioritize deadlifting or overhead above benching and squatting, the main movements and variations can be inverted. Plus Extra GPP Days Including: Sled Sprints, Sled Drags, Front Carries, Reverse Hyper, Back Extensions Pushups, Pullups, Isolation Work, Plyometrics, etc. We've talked extensively about advanced lifters requiring more specialization than less developed lifters. Getting to the top of the human-performance heap requires ever-increasing technical proficiency and they don't have the luxury of backsliding in the skill they spent so much time acquiring in the first place. The first obvious difference with this split is increased focus on 2 movements; we are no longer trying to develop all 4 big exercises at once because it's more difficult to do that and it doesn't lend itself to any competitive advantage. For an advanced powerlifter, the squat, bench and deadlift take priority so the overhead press becomes designated as a bench press supplementary movement. Every workout is led by a squat or bench because they generally respond well to more weekly touches and are generally harder to over-train. Improvements in the squat are also more likely to carry over to deadlift strength than the other way around. Of course, this isn't true for those who already squat substantially more than they pull so organize your Base phase around areas that need the most work. The Base phase will follow a volume/intensity split for the squat and bench. BASE MAIN PROGRESSION - UPPER AND LOWER 1 Micro 1 Micro 2 Micro 3 WAVE 1 65% x 4x6 65-70% x 5x6 65-75% x 6x6 WAVE 2 70% x 4x5 70-75% x 5x5 70-80% x 6x5 BASE MAIN PROGRESSION - UPPER AND LOWER 2 Micro 1 Micro 2 Micro 3 WAVE 1 Top 6 @ 6 3x4 Top 6 @ 7 3x4 Top 6 @ 8 3x4 WAVE 2 Top 5 @ 6 4x3 Top 5 @ 7 4x3 Top 5 @ 8 4x3 Stress has to be managed strictly so we use a more measured method of progression right out of the gate. A lifter who is just starting to reach basic strength bench-marks might look at these percentages and think that they are way too conservative, but trust me when I say that the rules change once squats, pulls and presses get into elite territory. The first microcycle of each wave is easy by design; it serves as a launching pad that allows time to adapt to the volume and leaves room for improvement over the rest of the wave (remember the truck driving into the mud). It will continuously serve as recovery week after each 3-micro wave, allowing the lifter to catch up and recover from the stress of the hardest previous weeks while they plan their jumps for the hard weeks to come. That recovery is absolutely vital for the continued progress of advanced lifters. The percentage ranges give us a solid guideline to plan our weight selection around and the progression sets the pace at which we increase and decrease stress. But it's a mistake at this level of performance to plan specific weights ahead of time based on an educated guess. We need some play in the joints for the days that don't go as planned or else the whole program could be sidelined by missed attempts that so often accompany poor recovery management. One approach I like is variable loading, where we set a range to work in and change the weight from set to set based on how we feel from each set. For example: In microcycle 1, 4 sets of 6 are all done with 65%. This is an extremely manageable amount of work and should rate low on the RPE scale. You may be more fresh or more run-down from the first 4 workouts than you might have expected so microcycle 2 can use variable loading to account for that. The range is 65-70% for 5x6, so a set each at 65%, 67%, 70%, 70%, 65% might be a pretty good day, whereas a day where fatigue is high might merit only one set at 70% with the rest at 65% (65/70/65/65/65). The goal should be to hit at least one set at the top end and keep all sets within this percentage range. By doing this, volume goes up each week along with average intensity, regardless of how you feel or what percentages were done with each set. The first microcycle of each wave doesn't require variable loading, since the efforts are so reduced anyways. But wherever there is a range of percentages listed instead of just one, play with the weights to keep the reps crisp and challenge your perception of how the weight feels in each set. BASE DEVELOPMENTAL VARIATION PROGRESSION Micro 1 Micro 2 Micro 3 WAVE 1 3x8 @ 6/10 3x8 @ 7/10 3x8 @ 8/10 WAVE 2 4x6 @ 6/10 4x6 @ 7/10 4x6 @ 8/10 The Base phase features relatively high reps for the developmental variations, though not quite as high as in the beginner and intermediate templates. Even with 'easy' weights, this can be a shock for advanced lifters who aren't used to so many sets and reps. Because we can't predict exactly how fatigue from the first exercise will effect the second movement, we use a rough RPE scale to find a good working weight. 6/10 means that each set had 4 or more reps left; there should be no real sign of strain. 7/10 is a bit challenging and 8/10 is showing plenty of strain while still leaving a couple of reps in the tank. If you start set one at an 8/10, I guarantee the weight will have to drop to keep it from getting to a 9 or a 10. That's ok. There should never be a missed rep, so drop the weight accordingly. Also, don't get hung up on making substantial weight jumps week to week. There will be weeks where fatigue is high and weeks where it is low, so let the RPE scale dictate what weight you choose that day and avoid forcing attempts that aren't there. I recommend keeping all of your exercises the same throughout the Base phase, only swapping them out if they present a substantial problem. Once you move into the Peak phase, the split and exercise selection will change to drive us further towards maximal strength. BASE TARGETED VARIATION PROGRESSION Micro 1 Micro 2 Micro 3 WAVE 1 3x6 @ 6/10 3x6 @ 7/10 3x6 @ 8/10 WAVE 2 5x4 @ 6/10 5x4 @ 7/10 5x4 @ 8/10 The targeted variations stay closer to a strength-specific rep range, partially because we want them carrying over to our heavier attempts in the peak phase and partially because it's harder to recovery systemically from overload movements done for high reps. BASE BODYBUILDING ACCESSORY PROGRESSION The smaller exercises are easiest to progress because they really can't be overtrained. High effort can be used in each set to create a response instead of tiptoeing around our recovery capabilities. Every accessory exercise should be in a range of 3-5 sets of 8-15 reps. How you distribute that is pretty arbitrary, so I leave it up to you. As long as effort is high and you are striving for a little more each microcycle, you will grow. Micro 1 Micro 2 Micro 3 WAVE 1 3x12 3x12 3x12 WAVE 2 3x10, 2 drop sets 3x10, 2 drop sets 3x10, 2 drop sets I recommend starting with a simple set and rep scheme for the first wave to give yourself a chance to get comfortable with the workload. By the second wave, your tolerance to work should be high, so kick it up with some of the advanced fatigue techniques later in the book. Rest/Pause, drop sets, supersets, partial movements.... they are all extremely effective at coaxing growth in stubborn areas and, if you're a masochist, they're kind of fun. BIG BULLY - PEAK PHASE LOWER 1 UPPER 1 LOWER 2 UPPER 2 Squat A Bench Press A Deadlift A Squat B Bench Press B Targeted DL Targeted Squat Targeted Bench Dev. OH Back Triceps R. Delt/Rot. Cuff Targeted DL Back Targeted Bench Dev. OH Triceps R. Delt/Rot. Cuff To peak for maximal strength, the fluff has to get replaced with more specific movements. We got rid of most of the bodybuilding accessory work here along with the developmental variations for the squat, bench and deadlift. We will keep the developmental overhead variations because they are an easier recovery option (we don't want overloaded overhead work pulling from our bench press peak) but they will be trained in a heavier rep range this time around. PEAK MAIN PROGRESSION - (A) Micro 1 Micro 2 Micro 3 WAVE 1 Top 3 @ 6/10 -10% x 5x3 Top 3 @ 7/10 -10% x 5x3 Top 3 @ 8/10 -10% x 5x3 WAVE 2 Top 2 @ 6/10 -10% x 4x2 Top 2 @ 7/10 -10% x 4x2 Top 2 @ 8/10 -10% x 4x2 Wave 3 Top 1 @ 7/10 -10% x 3x1 Top 1 @ 8/10 -10% x 3x1 Top 1 @ 9/10 -10% x 3x1 Test Deload Contest/Test The meat and potatoes of the advanced peak phase is a top set followed by repeating sets at a lighter weight. The RPE scale now dominates our decision making so that new found strength doesn't have to be hidden behind the guesswork of whoever wrote the percentages. Each microcycle, the difficulty climbs but the weight of each working set is ultimately based on your mental and physical state that day, so take it easy on the days you are dragging and let it fly when you have it. PEAK MAIN PROGRESSION - (B) Micro 1 Micro 2 Micro 3 WAVE 1 8x5 @ 65% 1:00 rest 6x5 @ 70% 1:00 rest 4x5 @ 75% 1:00 rest WAVE 2 6x4 @ 70% EMOM 5x4 @ 75% EMOM 4x4 @ 80% EMOM WAVE 3 5x3 @ 75% :30 rest 4x3 @ 80% :30 rest 3x3 @ 85% :30 rest The alternate days for the squat and bench keep volume and technical practice up while being reducing the work enough to bounce back for your next heavy day. There's a density component here as well, something I like to throw in to keep some stress when we can't afford to jack the weight up. I recommend treating these days like speed work; use compensatory acceleration (a fancy way of saying 'push as hard as you can the whole way') to condition the violent intent you will need on the platform. If this is actually a contest prep for you, practice how you play: put a deliberate pause on your presses and rebound hard with your squats. VARIATIONS FOR THE PEAK PHASE Targeted movement variations should include exercises that allow greater loads to be experienced.. Top-end heavy variations allow more load to be used which causes a substantial short term change in the nervous system. The lifter's ability to produce force goes up significantly and even the sense of how heavy a weight feels will change. If one movement is dedicated to working around a stick point, make sure the other is modified to allow the greatest load at the top end. Elevated deadlifts, slightly high box or pin squats, board presses, pin presses and, of course, accommodating resistance. As well as bands and chains work, they are trickier to setup correctly. If you have experience using them, go nuts. Just remember, there aren't any bonus points for it. If you aren't sure how to find the right amount of tension and don't train with someone who does, stick with one of the other variations. PEAK TARGETED VARIATION PROGRESSION WEEK 1 WEEK 2 WEEK 3 WAVE 1 4x4 @ 6/10 3x4 @ 7/10 2x4 @ 8/10 WAVE 2 4x3 @ 6/10 3x3 @ 7/10 2x3 @ 8/10 WAVE 3 4x2 @ 6/10 3x2 @ 7/10 2x2 @ 8/10 Each wave intensifies here, so work the dirt road. Week 1 is easy for more work, week 3 is harder and for less work. Take the variations seriously, your progression in them is vital to your progression in the main lifts. ACCESSORY WORK FOR THE PEAK PHASE We cut out most of the smaller exercises so that resources can be dedicated to the most specific activities. There are a few areas where we can't afford to decondition so we keep in a few token exercises. • Upper back strength is massively important for all of the lifts. After growing in the Base phase, the upper back tends to adapt pretty well to the demands of heavy squats and deadlifts in the Peak phase. But you don't want to put it on the back-burner for 3 full waves. Bent rows take up very little time and offer the most bang-for-the-buck of almost any exercise; if you are doing them on a regular basis, your back is going to stay strong. Keep the work at 3-5 sets of 5-8 reps. Chest supported variations can be swapped if the stress on the low back is too high. • Tricep strength is also of key importance to peaking a bench press. The targeted variations are top-end heavy so the triceps get a lot of pressingspecific work here. We can keep them growing as the weights climb by choosing a blanket extension exercise to run through the Peak phase. JM presses are a great tricep overload exercise (if they don't compound stress on your elbows). As with the rows, work these at 3-5 sets of 5-8 reps. Other heavy options are seated dip machines or any type of extension modified with heavy band tension. If these are not available, you can use a run-of-the-mill dumbbell or cable extension for some extra stimulation after your heavy pressing. • Rear delts and rotator cuff work need to stay present when you start chasing heavy bench numbers. Dumbbell external rotations, seated dumbbell cleans, face pulls and bent dumbbell raises are all effective and can be used as a warm up or at the end of the workout. I generally like these for higher reps but, if you've been doing them through the Base phase (like you should have) you will benefit by getting just a bit heavier. Keep strict form on all of them and pyramid through 12, 10, 8, 12. OPTIMIZING ACCESSORY WORK: ADVANCED FATIGUE TECHNIQUES Advanced fatigue techniques have existed in some capacity in bodybuilding for decades. If your sole mission is to grow mass, then all of the tactics you use to that end are going to be aimed at recruiting as many motor units as possible building up as much fatigue as possible. Early on, that might easily be done with a lot of repeating sets of high reps across a myriad of different exercises. You will eventually adapt to that, gaining muscle to deal with the stress of the workouts which will ultimately insulate you from the effect of that same stress. When adaptation causes progress to slow, more aggressive tactics have to be used to force further growth. In a strength-focused program, the main lifts have to take center stage, and that means pacing them so that we can plan our rate of progression and perform predictably well each session. This gets very difficult when you opt for a 'scorched earth' approach. The recovery cost of these advanced techniques is very high, so we avoid them with squats, presses and pulls. However, we can benefit from using them in smaller accessory movements which won't create the same degree of systemic stress that would happen with the main lifts. BLOOD FLOW WORK These are methods that encourage a nauseating amount of blood to pool into the targeted muscle. Remember that fatigue for the sake of it is a trigger for growth, regardless of whether it is a byproduct of hard work or simply preventing the elimination of waste product. 'Trapping blood' does require hard work and will recruit high threshold motor units, but it also creates a massive substrate deficit and bathes the surrounding area in lactate. Just like an oxygen-deprived climber will see their red blood cell count increase as they make it towards the summit, a muscle forced to work in extreme fatigue will adapt by increasing it's ability to store fuel and flush out waste. Even if this doesn't sound appealing to you in the slightest, this is a good tool to have in your belt. Blood flow work is extremely useful as a restorative method, since it doesn't require heavy load and it can force nutrients in and around tendons. The extreme local fatigue can also help in building kinesthetic awareness of lagging groups. If you struggle to feel your triceps contribute to a bench lockout or your glutes engage in finishing a deadlift, a few sessions of blood flow work will make you very, very aware of them. OCCLUSION TRAINING Blood flow restriction training (or Kaatsu, as it was named by the Japanese pioneer of the method) gained a bit of notoriety in social media over the last few years. It has all the markings of a gimmick and I don't blame you for being skeptical. While I doubt it will be the thing that takes you up a shirt size, it has some very useful applications if done the right way. Take a mini-band or floss band (or purchase a BFR cuff if you want to be legit) and tie it off like a tourniquet on your upper arm or upper thigh. It should be tight enough to restrict some blood flow but not so tight that you feel pins and needles or lose control of your limbs. Now, use some light isolation movement for 15+ reps (I frequently go 30-50 on some small movments) and clip off 5-10 sets with 20 to 30 seconds of rest in between. In the middle of this set, you will understand why animals chew their limbs off when they are trapped. The entire run of work should be around 5 minutes and the bands should stay on the entire time (though don't exceed that limit). The sets just serve to move blood and burn through atp; it is the actual time between sets, when the muscle is saturated in waste product it can't flush out, that the real magic is happening. When the cuffs come off, you will feel a massive flushing effect as new blood rushes in, creating a cushioning effect around the joints as a nice bonus. It's a nice way to hit the biceps without straining the elbow tendons, but the default application for strength purposes should be for tricep and quad/hamstring stimulation or for rehabbing inflamed tendons at the elbow or knee. I like small isolation movements, like cable pressdowns or leg extensions, but light compound movements like close grip pushups and lunges can be used as well. ACCOMMODATING RESISTANCE Bands and chains are commonly used in strength training as a way of providing more tension at the most mechanically advantaged points of the movement. While they aren't my favorite tool for for compound lifts for the general strength training population, they can be used easily and effectively with accessory and isolation work. The nature of AR is more work being done proportionately to straight weight, as the change in load accommodates where you are stronger or weaker. Momentum can be built up at the start when the load is light, allowing you to experience more 'heavy' touches at lockout than you would ever get with a bar or dumbbell. The protocol also allows more blood in while preventing waste product from flushing out, as the muscle is contracted hard under a heavy load at the top and stretched tight at the bottom. The result is the compounding of fatigue and a pumping effect that reminds me of putting air into a bicycle tire. Any isolation exercise can be modified to use accommodating resistance. Bands pressdowns are a common tricep finisher and doing skull crushers with chains attached to the bar is one of my favorite elbow-friendly moves. A band can be wrapped around the body and paired with dumbbells or a dhandle can be attached to a bundle of chains to force an extra squeeze at the top of a chest fly. Bands can easily be strapped to the pad of a leg-press, leg extension or hamstring curl machine. Adding bands or chains to hip hinges such as glute bridges, back extensions or good mornings will guarantee an ass-pump that you have never experienced before. Get creative, but understand that this should be a finisher after the heavy work. Take the reps deep, and I mean DEEP, into the cave of suffering and keep the rest periods well under a minute. PARTIAL RANGES OF MOTION Playing with the range of motion over a high-rep set is an easy hack to make the same weight work harder for you. One of my favorite methods came from a Ben Pakulski video where he used a 'double pump' technique on all of his isolation work. Basically, you lift to the top of the movement, squeeze for a second, release the weight by an inch, then squeeze again. That's one rep. 15lb dumbbells on an incline dumbbell curl led to some of the worst bicep DOMs I've ever experienced. Literally any movement can be modified like this, so go nuts. Just keep the reps high, the ROM full and the rest periods short. 21s are a classic example playing with the range of motion; the weight is moved through the bottom half for 7 reps, the top half for 7 reps and the full range for 7 reps. The early partial reps kick off the fatigue process and begin to flush blood into the muscle and that results in a muscle-tearing stretch with the full range reps at the end. It's a famous bicep burner that's often used for curls, but it can be applied to any isolation work and some compound movements. If you are the kind who likes challenges of pain endurance, strap yourself to a leg press and go through a few round of 21s at the end of your workout. X-reps tried to become a thing some 10 or 15 years ago and the idea never took off. It's probably because it wasn't a new idea, but how bodybuilders had been training for decades. The idea of an 'X-rep' is that range of motion is limited to the middle of the movement, never going all the way to the bottom or being locked out entirely. This serves to place all of the stress at the point of the movement that is more mechanically disadvantaged and never gets visited without some upward momentum being present. The lockout of a movement represents a point of rest, since there is high leverage advantage here, and the bottom benefits from the assistance of mechanical tension when the muscle is stretched like a rubber band. The middle is no-mans land and getting work there without the assistance of momentum or brief rest periods is a way to exponentially increase fatigue and high threshold motor recruitment with weights that won't beat down your joints. Blood also gets trapped as, similar to the other protocols, constant tension prevents the continuous flushing away of waste products. DENSITY WORK We have a lot of metrics for calculating stress (intensity, volume, number of lits, etc.) but density is rarely discussed. Any protocol that increases the ratio of work to rest counts as density work. Increasing density works as well as any other form of progressive overload, so much so that programs in the past (like Big Beyond Belief) have tried to make their name off of adapting lifters to shorter and shorter rest periods instead of simply adding weight. I credit density training as a key component for all of the world-class deadlifts that come out of strongman. Yes, deadlifts are a staple lift and have a lot of carryover to strongman events, so you would expect better deadlifters to be represented. But the sport features a lot of 'max reps in 1:00' deadlift events that force you to find the most efficient pace for optimizing reps in a specific period of time. That is density work. Building our main lifts around density would lead to unnecessary complication; we already have more than enough variables to play with and their aren't bonus points for using more. Accessory work, on the other hand, can get a nitrous boost from creatively applying protocols that pack more work into less time. ANTAGONIST SUPER SETS A super set is the execution of two exercises back to back without rest. Using antagonist muscle groups is a great way to get through the workload faster without building excess local fatigue that will limit the amount of weight being used. Lay out the smaller isolation workouts to be done and pair them together based on the different muscles used. Bicep curls go with tricep extensions, rows can go with delt work, hamstrings can go with quads, etc. It doesn't matter so much that they are pure antagonists, just that there is some local recovery for one muscle while the other is being worked. Perform one set, go right into the other, then rest one to two minutes. You will notice that general fatigue stays high, which is a benefit to general conditioning, and that a similar amount of volume can be done in a fraction of the time. REST PAUSE There are a few different protocols for rest/pause. I like to use a 3-round approach where each round is done to failure with only 20 seconds in between. That round represents one set and multiple sets can be done with several minutes rest in between. I like to shoot for a weight that puts failure around 15 reps on the first set, so that the sets go something like this: 15 reps - 20 seconds - 9 reps - 20 seconds - 5 reps. This works really well when you are short on time or if you have a lot of different accessory exercises and can't dedicate equal time to each one. SHORT REST PERIODS You can set a strict timer to make sure density stays as high as possible, using an 'every-minute-on-the-minute' approach or just trimming the rest periods. Try performing all of your isolation work with 30 seconds rest, dropping the weight as necessary to meet the rep goal, and see how substantial the increase in fatigue is. One of my favorite bench accessories was to do 5x15 with a fixed 60 seconds rest, adding weight when I was able to complete all reps in the time frame. The first day, I would always miss reps but would see massive increases in stamina in just a few workouts. I remember seeing new growth in my chest for the first time in years; it felt like I was benching to a cloud. If you are going to use it for a compound movement, keep it to machine or dumbbell work after the heavy stuff. POST-FAILURE SETS If you've ever come across the disciples of High Intensity Training, you've surely heard the good word about pioneers like Mike Mentzer and Dorian Yates. These guys credited their growth to reaching to and beyond the point of failure for just one or two working sets on each exercise, which flew in the face of traditional bodybuilding values regarding volume. The idea is that getting continuous gains requires pushing the body's ability to recruit high-threshold motor units and stimulate them for growth. to trigger that process, an exercise had to be done to complete exhaustion and then continued as far beyond that point as possible. There's controversy as to how well it stands as an entire training philosophy but there is absolutely no doubt that the ball-breaking work that pushes effort and fatigue to the limits has led to some pretty unbelievable outcomes. DROP SETS Doesn't get more straightforward when it comes to continuing past your limits. Pick a weight, go until failure, then drop to a lighter load and keep going. I've seen guys take this method to the limit by running down an entire dumbbell rack, accumulating a dozen rest-free sets in the process. I don't recommend going that crazy; these are the feats of pain endurance that seasoned bodybuilders participate in long after they've desensitized to generic training. Start with a weight that causes failure around 8 to 12 reps and drop it by a third once you've hit failure. Rest a few minutes, then repeat for 2 to 3 sets. You can add more drops to a single set later on when you've hit a plateau, provided you have the cajones. CONTRAST SUPERSETS These supersets will involve the same target muscles in both exercises. It's similar to the idea of a drop set but we are going to change the movement instead of the weight. Start with a heavier variation of the movement, whether it's a compound movement or just a more advantaged isolation movement, and aim for 6-10 challenging reps. Immediately move to a smaller isolation movement using a weight that allows you to push through 12-15 reps. An example for triceps might be a close grip bench, bar dips or french press for the 'heavy' version followed by rope pressdowns, kickbacks or bench dips for the 'light' version. The increased load used in the first movement primes the nervous system for force production. It's called post-activation-potentiation and the result is that you can physically do more work with the lighter movement. Compound that with the variety of motor units being used and the intense amount of fatigue accumulated and you have a recipe for uncharted growth. FORCED REPS This is every teenagers default approach to bench press workouts: pile on too much weight, squirm under the bar like a gaffed fish and wait for your buddy's two index fingers to give just the right amount of help. I'm not a fan of forced reps for the big movements. It's almost always an ego move that increases risk of injury and sidelines training rather than a calculated attempt at increasing stress. But, once again, accessory exercises benefit from a different set of rules. Success here assumes you have a partner you can trust and are capable of keeping strict form and position in the face of fatigue. TENSION SETS The first two categories were centered around increasing fatigue as much as possible inside of a working set. The methods laid out here focus primarily on another trigger for growth: muscle tension. Tension can be increased by using more weight or by slowing down efforts with moderate to heavy weights. Doing so increases fatigue but in the context of heavier loads which is an easy way to shock your system out of homeostasis. NEGATIVES Muscles go through 3 types of contraction: concentric (moving the weight up), isometric (staying still) and eccentric (lowering the weight). Concentric is where we see most of the work is being because, obviously, moving the weight against gravity is the hard part. But the human body can handle much, much more load on the eccentric and we can use that fact to increase stress. It has been suggested that the eccentric portion of the lift, or the negative, correlates to muscle growth more than the concentric. Systems that involve a lot of eccentric movement (like bodybuilding) feature more muscle tissue breakdown and more delayed onset soreness than systems that don't (like Olympic lifting). Non-eccentric movements like sled work are great restorative movements on off-days for that reason; they only use concentric movement so they don't compound tissue breakdown. I'm not advocating pure negative work using maximal weights and forced reps on the concentric. Keep the negative work to accessory stuff and work through the entire set on your own. You might have to start a bit lighter than with a straight set but that's fine. Sets of dumbbell presses, tricep extensions, good mornings and the like are brutal when done for a 5 count or more on the lowering phase. TEMPO Slowing the weight down on the concentric phase works similar to 'X-reps'; control and effort has to be displayed at the middle-parts of the movement that are usually aided by momentum. I like tempo work for activation purposes when lagging muscles don't seem to come online very easily. After a couple of sets, the muscle should be full of blood and twitchy and that should lend itself to a greater sense of awareness when it is being used during a major lift. The tempo doesn't have to last forever, just make a conscious effort to hold your movement to a 3 count on both the concentric and eccentric. You can even pause at the bottom if you are feeling spicy. CHEAT WORK Cheat sets get a bad rap because of the people who implement them the most; underdeveloped white belts looking for a reason to throw an extra quarter on the curl bar. Remember, these are advanced fatigue techniques, meaning they should be implemented after the simple stuff has been milked for all it's worth. The important point with cheat work is that it is not a 'get the way up at all costs' approach. The mechanics of the strict version should still be present and just enough sway should be used to give a small bump in weight or the amount of reps done. When done right, there is a smooth rythm to it. Use them for upper body movements like curls, delt raises, push presses, kroc rows, etc. GPP WORKOUTS General conditioning is one of the most overlooked things in strength training culture. If you spend half your life in the gym, it stands to reason that your physicality should at least outpace a newborn baby. As a strongman competitor who needs to display proficiency in 178 different activities at any given time, I got a big leg up by putting light event work on my off days. Loads, carries and sled work kept those events sharp so I could spend most of my time on events that were weak or coming up in my next show. Where I thought the extra work would beat me down, it actually had the opposite effect. Putting 30 minutes to an hour of general preparedness workouts in your off days will help recovery, increase stamina, reduce body fat and even contribute to growth by increasing weekly volume. There's just no good reason not to. MOBILITY/FLEXIBILITY WORK I'm not even going to humor the controversy around this type of work. If you are the type of person who maintains average or above-average flexibility as you grow from training, then great. But any PT or chiropractor who regularly works on long time lifters will tell you that isn't the norm. You don't need to work to be a ballerina or master yogi. Just prioritize some time to making sure your joints can move through an adequate range of motion. Doing so will prevent the extremely common injuries and overuse issues that come from moving heavy weights poorly. • Foam Rolling/Myofascial Release While I'm not a supporter of the '30 minutes of rolling before you get under the bar' crowd, it does have some utility and should be thrown in to address some movement issues and prevent new ones from popping up. Upper back, erectors, quads, glutes, hammies and hip flexors are the big areas to focus on and they can be thoroughly ran through in about 5 minutes. You can also use a lacrosse ball to get into the shoulders, biceps and pecs, but don't get carried away. At some point, you're just better off booking a massage. • Dynamic Stretching You might remember these from high school football; they represent a good general warmup that encourages flexibility without sapping power production. Cossack squats, walking high knees, cariocas, straight leg kick, power skips are a few examples. Use them to warmup in a pinch, but don't bank on them to fix severe inflexibility. • Static Stretching Controversy started here because some studies show what a lot of veteran lifters already knew: a long deep stretch right before a heavy strength exercise will lower force output. I read that to say "don't do a 5 minute long hamstring stretch if you are planning to attempt a deadlift PR right after". Most power sports benefit from flexibility (gymnastics, olympic lifting, football, etc.), so if you are lacking, you need to do some longer holds. Glutes, hams, hip flexors, lats, delts and pecs are the big areas, so get on Google and find a few basic stretches to focus on for 6 weeks at a time. 90 seconds is the minimum but I really like 5 minute challenges with squat or toe-touch holds. The difference in movement ability right after is astounding. SLED WORK Sled work is fantastic as a GPP exercise because it doesn't have an eccentric phase, which is responsible for most tissue damage. Any variation of pushes or backwards drags will get blood into the quads, glutes, hams and calves which drives nutrients and accelerates the recovery process. They have been known to help slap extra muscle on the thighs and to be a rehabilitative tool for creaky knees. And the conditioning effect is second to none. They can be done for slow, continuous work or they can be done all out for set intervals. Just stay consistent and make small improvements each week. • Backwards Drag Great for the quads and knees without over-stressing the tendons or digging further into the recovery hole. You can do short, heavy sprints on a time interval or long, continuous work (I'm a fan of 5 minute runs of continuous dragging). After a few months of dragging sessions in between regular squat workouts, you should notice your pants getting a little tighter around the thigh. • Prowler Push Sled sprinting is one of the best conditioning exercises I can think of. It improves your ability to recover from short, all-out efforts, which has benefit to athletes and lifters alike. I don't like going too heavy, since footslippage will become the limiting factor. Instead, position yourself with arms extended, like a spear, and cycle your legs through a full range of motion. Exaggerate high knees and full extension and turn your feet over quick. If you are new, take a minute in between each round of 50' or so. As you condition, 100' runs at around :30 rest can be done for 8 to 12 rounds. • Forward Drag Attaching a strap around your hip is a better method for slower forward pulls. The dynamic puts more strain in the hamstrings and glutes and doesn't lead to foot slippage or require a ton of weight. Set a goal time or distance to move continuously through before taking a break. A few rounds of 200' or one big ruck at 500-1000' will be about right. • Upper Body Work w/ Straps A strap with a sled can allow the upper body to benefit from the concentric only work. Execute the movement like you would on a cable tower, walk forward and repeat. This can be done with chest flys, rear delt raises, rows, pushes, extensions, curls, etc. Keep the weight light and don't get sloppy. Remember, this is restorative as much as it is developmental. PLYOMETRICS For anyone interested in developing a wider athletic base, explosive work can be included to benefit faster activities. Those in team sports, track and field athletes, fighters and strongmen can all benefit from an extra boost in their step and GPP days are a great opportunity to include them. Lower body stuff has the most real-world carry over, but explosive upper body workouts can be done to round you out and create a conditioning effect. • Med Ball Throws/Slams The ease of setup and execution with slam balls makes them a default staple in conditioning circuits. Pick up the ball, bring it overhead and use your whole body to slam it into the ground (hitting a tire with a sledge hammer brings a similar result). You can get creative with slams to mix it up. I like 'squat, throw, chase' as a sequence, wall balls and rotational wall slams. Repeat for a few rounds on and interval or opposite of other wholebody movements and try not to vomit. • Conditioning Plyos When in doubt for a conditioning stimulus, just take an explosive body weight movement and do it for high reps. Burpees, mountain climbers and simple squat or split jumps fit the bill. • Jumps You can keep the nausea down and instead emphasize pure power development over conditioning. If you are trying to increase something like a vertical jump or a throw, you want to be recovered and fresh for each jump so you will avoid fatigue. Depth jumps, squat jumps, split jumps, broad jumps, seated box jumps (and the million ways you can vary them) can be done for many low-rep sets on off-days to condition speed. • Upper body (clap pushup/kipping/muscle-ups) Few activities have a direct benefit from upper-body plyometric work over general strength training but they still pack a big conditioning effect. Chest passes and throws with a slam ball count but we can add movements like clap push ups, kipping pull ups and muscle ups to the list. And save your weirdo dogma about kipping; I'm discussing potential conditioning tools, not telling you to replace barbell rows with kips. If it works as a tool for the best gymnasts in the world, certainly your squishy, potato of a self isn't too good for them. At a time when I could do 23 strict pull ups, 15 kipping pull ups would leave me out of breath for about 2 minutes, so they work as advertised. BODYWEIGHT RESISTANCE Movements using just your body weight as resistance should be a staple. Their effect on general physical ability is pronounced yet they are extremely easy to recover from. The can easily be included as extra legs of a circuit or on an interval. Pushup and pullup variations are one of the best way to add upper body volume to your week. I recommend modifying them so they can be done for higher reps instead of grinding through low rep sets with the standard setup. As you advance, they can be done with harder variations. Other movements like bench dips, lunges and body weight squats can be done as part of a circuit to move blood around and get your heart rate up. BANDED WORK We covered banded work in the section on Advanced Fatigue Techniques. The increase in blood flow is restorative in nature and the movements don't compound stress on the joints. The high threshold that band movements work through increases general capacity as well, building you up so that more work can be done more often. Use these to target lagging muscles or problem joint areas. Triceps and bicep work, or any work targeting the elbow joint, can be done simply by using a band for curls or pressdowns. Mini bands can be fixed to barbells as well, but I don't recommend using very much straight weight. Straight arm pulldowns work well for the lats and face pulls and rotation will get the muscles of the rotator cuff. If you have ankle cuffs, you can use straight band tension for quad and hamstring work, but fixing the bands to a machine is an easier option. Remember to keep the reps really high and the rest periods short. BRACING WORK This is the work everyone needs the most but does the least. Strong abs are important (you can't squat or deadlift effectively without them) but lifters get so enthralled with evaluating different training progressions or trying new movement variations that they let the midsection collect dust. Traditional ab work, like situps and leg raises, aren't the only way. In fact, I don't like them that much. Most fall short in learning how to use the muscles of their midsection as one stable unit and the individual strength of a muscle doesn't matter if it's not getting used correctly. These bracing exercises help drive that point home. • McGill 3 The curl-up, bird-dog and side plank have been dubbed "the McGill Big 3" after world renowned spine specialist Stu McGill. They teach you what sit ups and leg raises don't; how to maintain a braced midsection that limits movement of the spine. The protocols for these are vital in that they focus on building endurance before building strength, so save the weighted sit ups until you can actually make it through these movements without falling apart. • 90/90 breathing I learned about this some years back at a Juggernaut seminar that featured the Darkside Strength guys, Ryan Brown and Dr. Quinn Hennoch and it is probably the only reason that I've been able to keep competing in Strongman. Lay on your back with your feet on the wall, hips and knees at 90 degrees. Pull your abs in to your spine and brace. Keeping them tight as possible, breath into your stomach for a 5 count, using the resistance of the abs to redirect air up into your lungs and rib cage. Then blow out as hard as you can, squeezing the abs to force the air out. If you do it right, it sucks. At first, a few rounds of 3 or 4 breaths will wipe you out. Work up to 8 or 10 without your belly going soft and the benefit to your barbell lifts will be obvious. • 'Anti' Movements The key to bracing is conditioning the muscles of the midsection to limit spinal movement and to do so longer. One effective way is to use an external resistance that works to pull you out of position. The list of movements fall under the umbrella of anti-rotation, anti extension and antilateral flexion depending on which direction the force is trying to pull you. Most off-set movements do this automatically, like waiter carries, singlearm farmers carries, shovel deadlifts, etc. Pallof presses are one of my favorites because they are slow and reinforce awareness and receptivity in the midsection. Fix a mini band at shoulder level to a squat upright in front of you. Turn 90 degrees to the side, holding the end of the band in both hands, and take several steps to the side until the band is tight. Stand rigid, push the band out and bring it back; 5 count out, 5 count in. As the point of resistance moves away from you, bracing becomes more difficult. A few sets of 10 is usually good enough to get the abs quivering. GOOD OL' CARDIO Every time I see someone share that cardio is 'sets of 5' or 're-racking my weights', I want to hurl a barbell through the wall. The appeal of being strong is that it makes you useful. Deteriorating into a sweaty, wheezing mess after the 30 second mark of any physical endeavor makes you anything but. Fellas, just ask your ladies. The EASIEST way to avoid such a fate is to plant your ass on any one of the extraordinarily engineered yet easily accessible pieces of machinery that living in the 21st century grants you access to. Or just go move around outside for a while. The thing about cardio is that you don't need to train to be Prefontaine; just move continuously with an elevated heart rate for 40 minutes or so and you will see your capacity in the gym sky rocket. EXAMPLE GPP WORKOUTS DAY 1 DAY 2 Day 3 Foam Rolling Cossack Squat (3 x 8 each) Squat Hold (3 min.) Lat/Rotator Stretch (2 x :30 each) Foam Rolling Couch Stretch (3 min.) 90/90 Breathing (4 x 5 breaths) Pallof Press (4 x 8 per side) McGill Curl Up (4 x 5) Dead Bug (4 x 8 each) 90/90 Breathing (3 x 8 breaths) Side Plank (3 x :30 per side) Circuit: (3 rounds, 20 each) Squat Jump Pullups Bench Dips 30 Minute Walk on Incline Circuit: (5 rounds, 10 each) Med Ball Throws Kipping Pullups Single Arm OH Squat Sled Sprint 5x150' Band Circuit: (50 each, 3x) Pressdowns Curls Flys Face Pulls Sled Drag 500' continuous