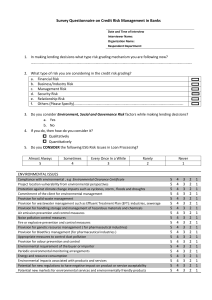

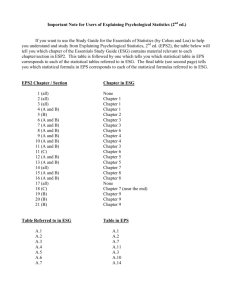

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/0307-4358.htm Can student managed investment funds (SMIFs) narrow the environmental, social and governance (ESG) skills gap? Erin Oldford Faculty of Business Administration, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada SMIF and ESG pedagogy 57 Received 8 July 2021 Revised 27 July 2021 31 July 2021 Accepted 5 August 2021 Neal Willcott Smith School of Business, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada, and Tanner Kennie Faculty of Business Administration, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, it endeavors to document the current state of environmental, social and governance (ESG) pedagogy within undergraduate finance courses of business schools, and second, it seeks to show how business schools can leverage student managed investment funds (SMIFs) to swiftly integrate ESG pedagogy. Design/methodology/approach – The study is comprised of two sections that use different methodologies. The first part of the study involves a manual content analysis of undergraduate finance course textbooks, and related instructor materials are used to estimate the average coverage of ESG-related topics. Next, a case study of a SMIF that has recently integrated an ESG framework is provided to illustrate how this pedagogical innovation is effective in teaching ESG skills. Findings – The findings of the content analysis of the three most commonly used textbooks in a sample of 17 Canadian universities, as well as associated instructor material, provide evidence that the primary emphasis in traditional curriculum remains on the shareholder, with little attention paid to ESG factors. The case study of an existing SMIF clearly demonstrates how a student-led development of an ESG framework provides the setting for effective, experiential learning. Originality/value – This study shows that while traditional teaching settings, like lectures, may be slow to adapt to the rapidly changing needs of industry, nontraditional teaching venues, such as SMIFs, can be leveraged to meet industry demand for ESG skills, thereby closing the skills gap, enhancing student employability and increasing the relevance of business school education. Keywords ESG, Experiential learning, Business schools, Student managed investment funds, SMIF Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Sustainable finance is the study of finance through a lens that accounts for the environmental, social and governance (ESG) costs and benefits of a project (Fatemi et al., 2013). In general, financial strategies have the goal of shareholder wealth maximization (Friedman, 1970). More and more, academics and practitioners are recognizing that ESG factors are an intrinsic element of shareholder value (Henisz et al., 2019; RBC Global Asset Management, 2021; Glossner, 2018). As a result of the increasing role that ESG philosophy has on investment decisions, it is gaining traction among academics, policy makers and practitioners, alike (e.g. Alsayegh et al., 2020; Liu, 2021). Given the growing importance and JEL Classification — A20, G11 This research was supported by funding from CPA Newfoundland & Labrador. Managerial Finance Vol. 48 No. 1, 2022 pp. 57-77 © Emerald Publishing Limited 0307-4358 DOI 10.1108/MF-07-2021-0317 MF 48,1 58 attention paid to ESG factors, along with superior returns linked to ESG (Friede, 2015; Nagy et al., 2016; Morbiato, 2021), we anticipate that ESG issues will become increasingly important to shareholder value and the market over time. Presently, this shift has encouraged many firms to implement shareholder policies and practices that consider all stakeholders involved, including the environment and the global community (Freeman and Liedtka, 1997), a perspective generally described as stakeholder capitalism (Sundheim and Starr, 2020). Many consider stakeholder capitalism as the best response to the social and environmental challenges currently facing society (Schwab, 2019; Stiglitz, 2019; Hunt et al., 2020). In this way, ESG, sustainable finance and stakeholder capitalism are closely related concepts driving change in the investment industry and beyond. In practice, ESG factors are used as a way to analyze a firm’s exposure to a comprehensive set of risks and opportunities that are not traditionally incorporated into analyses (e.g. climate risk and equitable treatment of workforce) (El Ghoul et al., 2011; Ashwin Kumar et al., 2016). Research shows that by measuring, reporting and benchmarking ESG performance, investors can better understand a firm’s future profitability (Freeman and Liedtka, 1997; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Flammer, 2015; Fatemi et al., 2018). In 2014, ESG-driven investment represented 31.3% of assets professionally managed in Canada (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018) and in 2020, that figure grew to 61.8% (CAD $3.2 trillion) (Responsible Investment Association Canada, 2020). The growth in sustainable funds has been consistent across developed nations (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018) and is, therefore, a sign of a rapidly changing investment landscape. Due to the growing role of ESG in the financial industry, ESG skills have become important to firms, investors and policy makers. ESG skills refer to the specific skillset that facilitates the application of nonfinancial ESG factors as part of financial analysis (CFA Institute, 2021). Some examples of ESG skills necessary to support the ESG movement include benchmarking ESG performance, quantifying ESG risks and opportunities, and developing and communicating ESG disclosures. Table 1 summarize central ESG skills currently in demand by industry, and these data are based on interviews with ESG professionals along with publicly available ESG-related job postings. Meanwhile, media coverage shows that the investment industry “cries out for trained finance professionals” (Murray, 2020, p. 1), and furthermore, Pronina and Rocha (2021) report that banks and corporations are scrambling to hire people with ESG skills, at all levels of the organization. To illustrate, PwC recently announced its intention to invest $12bn over five years to create 100,000 new jobs to support ESG reporting and advising (Dinapoli, 2021). However, the CFA Institute (2020) performed a review of more than 10,000 LinkedIn profiles of investment professionals and found that only 6% of profiles mentioned ESG-related skills, suggesting a gap may exist in the industry demand for and supply of ESG skills. A possible explanation for the skills gap is greenwashing behavior (Delmas and Burbano, 2011), where firms recruit and hire for ESG positions (i.e. competence washing, Schumacher (2020); Minh (2021)), as a tactic to be publicly perceived as adopting sustainable practices without actually doing so [1]. However, the extant literature has shown that investors are becoming more sophisticated and effective when identifying greenwashing behavior (Pronina and Rocha, 2021). Furthermore, research shows that greenwashing is harmful to firm profitability (Szabo and Webster, 2020), and recently, firms have begun implementing strategies to minimize competence washing, such as establishing accepted taxonomies and minimum standards for a title of “ESG expert” (SNEU, 2021). Thus, the ESG skills gap is likely a genuine lack of ESG skills in the current labor force. The purpose of this study is to examine this ESG skills gap. To this end, we first assess the state of ESG skills development within business schools by performing a content analysis of ESG-related concepts within conventional teaching materials (i.e. textbooks and instructor slide decks) of 17 Canadian business schools. We uncover a marked absence of ESG training within traditional undergraduate programming. Given that the content of conventional, lecture-style teaching methods are typically slow to adopt new material (Schlegelmilch, 2020), Investment finance ESG trends ESG information collection ESG information analysis Investment analysis Investment criteria Investment products Understand industry and national regulatory trends Understand national disclosure trends Understand ESG trends (e.g. climate volatility and real estate values; human resource practice of hiring a short-term workforce) Be aware of sources of ESG data and the quality of each Determine materiality of ESG factors for a given company or industry, for example, by employing the SASB materiality map Understand technical elements of ESG (e.g. biodiversity and social inequalities) Understand the methodology of ESG ratings (e.g. Sustainanalytics) Question companies on ESG disclosure and performance Evaluate the quality of ESG data disclosed Evaluate the absence of ESG data disclosed Benchmark ESG performance (e.g. past performance, peer analysis) Perform qualitative assessments (e.g. identifying if ESG strategy is in line with ESG performance) Perform quantitative assessments (e.g. build ESG opportunities into projected cash flows and build ESG risks into discount rates) If using an exclusionary approach, establish ESG screens (e.g. percent women on boards and carbon emission rates) If using an impact investment approach, establish consistent approach incorporating ESG research into investment decision-making Understand ESG-related investment products (e.g. green bonds, ESG mutual funds, etc.) Be aware of and understand financial innovation trends in ESG SMIF and ESG pedagogy 59 Corporate finance ESG information disclosure Identify current and anticipate future material ESG factors Determine the method and frequency of disclosure Understand industry and national regulatory trends Understand national disclosure trends Understand company and industry exposure to ESG risks Understand the link between disclosure and the cost of capital Understand the methodology of ESG ratings (e.g. Sustainanalytics) ESG strategy Set ESG targets Establish internal ESG benchmarks Measure ESG performance Communicate ESG strategy and performance to stakeholders (e.g. employees and investors) Note(s): This table displays examples of ESG skills currently in demand by industry. Data is collected from interviews with industry professions and current ESG-related job postings particularly when the topic is still in development, as is the case with ESG in the finance industry (Murray, 2020), we contend that an alternative teaching strategy is necessary to narrow the skills gap. We propose an innovative solution to the state of ESG training in business schools. We describe how a student managed investment fund (SMIF), an experiential learning program common among many business schools (Lawrence, 2008), can integrate ESG training to promote skills development. In this setting, ESG training can be integrated quickly, thereby providing students with a robust skill set prior to entering industry while also contributing to the narrowing of the ESG skills gap. This research makes a number of important contributions to both academic research and practice. First, the research contributes to the large body of research on the relevancy of business schools (Muff, 2012). More specifically, our research shows how business schools can leverage nontraditional teaching methods to become nimbler and more relevant to Table 1. ESG skills MF 48,1 60 practice. Second, our research contributes to the small, albeit, growing stream of SMIF research. Our research also answers the call by Abukari et al. (2021) for more research on innovations within SMIFs that parallel innovations in industry, including ESG. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. We first provide a background on sustainable finance and ESG factors, considering contributions from academia, policy makers and practitioners. Next, we examine the current state of ESG-related training in the traditional undergraduate curriculum of business schools. An account is then provided of the experience of a SMIF program that has developed and integrated an ESG framework, as a nontraditional, albeit potentially effective, approach to teach ESG skills. Finally, we synthesize the findings and provide concluding remarks. 2. ESG: A brief background The field of sustainable finance began as a niche concept, popularized in the early 1990s with Porter’s (1991) essay “America’s green strategy”. In this paper, Porter argued that firms need not choose between profitability and pollution reduction, and that pollution was wasteful and damaging to shareholder value. Since then, both the academic and professional community have continued to study and discuss the significant costs associated with inaction in mitigating climate change (Stern, 2007; Gardner, 2015; Gencsu and Mason, 2018). In more recent years, the field of sustainable finance has expanded its scope beyond just environmental concerns to include social and governance factors such as inclusivity, equity and transparency while also maintaining profitable business practices (Accounting for Sustainability, 2019). Sustainable finance and the associated ESG factors aim to provide investment that is focused on not just sustainability for current practices but more broadly, to build a better world (PWC, 2019). A growing body of practitioner and academic research shows that embedding ESG into corporate practices is value accretive. For example, a McKinsey 2019 Global Survey on ESG programs reports agreement among executives that ESG policies increase shareholder value (Hunt et al., 2020). Academic research investigates the link between ESG factors and corporate financial (e.g. Brogi and Lagasio, 2019) and social (e.g. Alsayegh et al., 2020) performance. Evidence from this stream of research shows that businesses that implement ESG practices have lower costs of capital (Fatemi and Fooladi, 2013; Dhaliwal et al., 2011; El Ghoul et al., 2011), superior financial performance (El Ghoul et al., 2011) and fewer capital constraints (Cheng et al., 2014; Hauptmann, 2017). Much of this work has concluded that ESG factors are integral sources of firm value (Fatemi and Fooladi, 2018; Goldman Sachs, 2017; Kahn et al., 2016). ESG investing involves investors incorporating ESG factors into portfolio construction decisions. This is a strategy that involves investing funds in companies that strive to make the world a better place by working to mitigate climate change, create social good and increase corporate transparency (Napoletano and Curry, 2021). ESG factors have been studied in conjunction with profitable investment strategies (Ielasi et al., 2020), and studies have found that sustainable investment has a positive effect on equity returns (Friede, 2015; Nagy et al., 2016). Investment in firms that have strong ESG performance, while divesting from firms that have weak ESG performance is a mixed strategy that pressures companies to improve their practices in the hopes of attracting and retaining investors (Amenc et al., 2020). Given their financial and social influence, institutional investors play a central role in encouraging firms to incorporate and disclose ESG-related factors (Eccles et al., 2017; Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018; Arabella Advisors, 2018). Institutional investors are the largest and most informed investors in the financial market. Over 1,600 institutional investors, representing $62 trillion in assets, have signed the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investing and are embracing ESG as the next major investment opportunity (Eccles et al., 2017). To illustrate, in Larry Fink’s, CEO of Blackrock, 2020 Letter to CEOs, he stated that he considered sustainability to be “at the center of our investment approach,” and that Blackrock was taking action “making sustainability integral to portfolio construction and risk management; exiting investments that present a high sustainability-related risk” (Fink, 2020). In August 2019, 181 multinational CEOs of the Business Roundtable revised their statement on the purpose of a corporation to explicitly focus their practices on a “fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders” rather than simply favoring only shareholders (Business Roundtable, 2019). As empirical research continues to support the practice of ESG being profitable (Eccles et al., 2017; Nagy et al., 2016; Fatemi and Fooladi, 2013; Dhaliwal et al., 2011; El Ghoul et al., 2011; among others), retail investors are also increasingly attracted to firms that make sustainable investments. Despite the shifting sentiment of ESG investment, data remain a significant barrier. The challenge with ESG data is that there are no established standards with a curation for quality and no accepted practice on how these data can be used (Ecceles et al., 2017). In a survey, investors agreed that a lack of measurement standards for data was a barrier to ESG integration, and that stronger reporting standards would provide better integration of ESG factors (Ecceles et al., 2017). In the past 10 years, regulatory action to include ESG as a standard in financial disclosures has accelerated significantly (Grewal et al., 2020; AmelZadeh and Serafeim, 2018); however, there is still no widely accepted standard, despite broad agreement that there is a lack of standardized regulation around ESG integration (Eccles et al., 2017). Currently, the SEC is considering the inclusion of more rigorous disclosure and regulatory standards for ESG (Grewal et al., 2020). With sustainable finance causing a shift in the investment industry, it is likely that a wide range of professions at the various levels within the finance industry (as well as within firms) require a deep understanding of ESG factors. The industry, however, is struggling to find candidates with this knowledge, which suggests the presence of a skills gap (Pronina and Rocha, 2021; Murray, 2020). In the subsequent section, we investigate business schools, the initial training ground for many investment professionals, to assess the degree to which ESG training has been integrated into traditional, lecture-based curriculum. 3. ESG pedagogy in business schools The past decade has witnessed a movement in management education to integrate sustainability, which, as Gitsham and Clark (2014) show, has been driven by industry demand [2]. The substantial literature (e.g. Akrivou and Bradbury-Huang, 2015; Seto-Pamies and Papaoikonomou, 2016; Walck, 2009) is dedicated to how sustainability can be integrated into management education, and now, most business schools have sustainability courses, if not specializations or graduate programs, in sustainability. Yet, from our search of the literature and current undergraduate curriculum in Canadian business schools, there appears to be little emphasis on sustainable finance and ESG factors, which could be explained by either a resistance to change among those in the finance discipline (Raelin, 2009) or a lack of consensus among those in the finance industry on how to assess, value and integrate ESG into investment and portfolio analyses (Murray, 2020). The first aim of this research study is to understand if universities are, in fact, preparing business students to meet market demand for ESG-related skills. Specifically, we seek to investigate the degree to which sustainable finance and ESG technical skills are, on average, taught within introductory-level finance courses of undergraduate business programs. From our survey of Canadian business schools, an introductory finance course is typically offered over two terms and provides a survey of topics in corporate and investment finance, and therefore, curriculum in these courses provides insight into the presence of foundational ESG skills within the finance specialization of business schools. SMIF and ESG pedagogy 61 MF 48,1 62 To investigate our first research question, we examine ESG coverage in introductory finance course textbooks and associated instructor slide decks used within 17 Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) business schools in Canada. We expect that textbooks and teaching guides are illustrative of the key topics taught within the course as many instructors rely upon textbook materials as a basis for instruction (Ransome and Newton, 2018; Yerushalmy, 2014). Furthermore, the course textbook often represents the collective beliefs of the profession on what is important for a particular course topic (Berry et al., 2010). However, we do acknowledge that the evaluation of textbook content may not be completely representative of what is being taught within the classroom by the instructor. We also considered evaluating course outlines; however, upon an extensive search, we found that few instructors make their course outlines publicly available. We collected textbook data on Canadian business schools accredited by the AACSB through university bookstore listings. AACSB institutions were included as these have made a uniform commitment to industry relevancy (AACSB, 2020). We selected to observe Canadian business schools because we were able to obtain a representative sample, and furthermore, an early investigation of course textbooks in the United States provided consistent results as the Canadian sample. Table 2 displays the adoption rates for each textbook, and the results indicate that there are three textbooks in use at our sample of business schools, with the dominant one being Ross et al. (2019), which is used in 74% of our sample. In addition to textbooks, we also collected associated instructor slide decks. We then used content analysis to assess the coverage of ESG topics in these materials. Content analysis (Krippendorff, 2018) involves using validated dictionaries of words to assess the language employed in written texts and has been widely used in a variety of research fields, including finance and accounting research (e.g. Fiset et al., 2021; Kothari et al., 2009). In this study, we use two dictionaries (see Table 3). The first is a stakeholder dictionary established by Crilly and Ioannou (2017), where a list of terms was developed from an assessment of stakeholder-related items of vocabulary in letters to shareholders. The terms are divided into seven categories: shareholders, employees, customers, communities, natural environment, government and suppliers. The second is a sustainability dictionary developed by Wu et al. (2010) for their global study of sustainability coverage in management education. To our knowledge, there is no validated ESG-specific dictionary, but it is our view that by observing both aforementioned dictionaries, we provide a conservative assessment of ESG coverage. Citation Ross-text Ross-slides Table 2. Finance textbook adoption Adoption rate (%) Total chapters Estimated total words Ross, S. A., Westerfield, R. W., Jordan, B. D., 73.8 26 688,275 Roberts, G. S., Pandes, J. A. and Holloway, T. A. 67,207 (2019). Fundamentals of corporate finance. (10th Canadian ed.). McGraw Hill education BrighamBrigham, E. F., Ehrhardt, M. C., Gessaroli, J., 15.8 23 455,616 text and Nason, R. R. (2017). Financial BrighamManagement: Theory and Practice. (3rd 78,132 slides Canadian ed.). Nelson education Ltd Berk-text Berk, J., DeMarzo, P., and stangeland, D. (2019). 10.4 31 769,856 Berk-slides Corporate Finance. (4th Canadian ed.). Pearson 117,554 Canada Note(s): This table displays the textbooks and instructor slide decks used in this study. It also shows the adoption rate of each resource by 17 AACSB business schools in Canada Colleague(s) Employee(s) People Union(s) Worker(s) Workforce Consumer(s) Customer(s) Patient(s) Citizen(s) Climate Community/-ies Neighbor(s) Neighbor(s) Communities Conservation Emission(s) Environment Footprint Greenhouse Nature Renewable(s) Waste Natural environment Authority/-ies Government(s) Legislation Legislator(s) Regulation Regulator(s) Government Constractor(s) Manufacture(s) Partner(s) Suppliers Biodiversity Environmental health and safety Poverty prevention Climate change Environmental stewardship Race relations Community engagement Equal opportunity Recycle Corporate citizenship Ethics Renewable energy Corporate environmental responsibility Fair trade Reuse Corporate environmental responsibility and accountability Gender equality Rural development Corporate social responsibility (CSR) Greening Sustainability Culture and diversity and intercultural understanding Human rights Sustainable development Disaster prevention and intercultural understanding Market economy Sustainable growth Disaster prevention and mitigation Natural resource Sustainable procurement Ecology Natural resources management Sustainable urbanization Ecosystem Peace and human security Triple bottom-line Energy Pollution management Waste Note(s): This table displays the dictionaries used for content analysis of lecture materials, with Panels A and B listing dictionary words from Crilly and Ioannou (2017) and Wu et al. (2010) Panel B: Sustainability dictionary (Wu et al., 2010) Investor(s) Shareholder(s) Shareowner(s) Stockholder(s) Panel A: Stakeholder dictionary (Crilly and Ioannou, 2017) Shareholders Employee Customers SMIF and ESG pedagogy 63 Table 3. Dictionaries for content analysis MF 48,1 64 Typically, content analysis employs software tools, such as LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count), which captures the number of dictionary terms as a percentage of the entire text. As we did not have access to text files of the textbooks, six research assistants performed hand-coding of all textbooks and instructor slide decks. We divided the research assistants into three teams of two to ensure inter-rater reliability, and each team assessed one textbook and associated instructor slide deck. Following a team’s coding, coders provided a check of inter-rater reliability, and the inter-rater reliability in terms of agreement percent for the first team was 95.1%, the second team was 93.3% and the third team was 96.7%. To estimate the total number of words in a text, we counted the number of words on 20 pages and used the average number of words and multiplied that by the number of pages per chapter and textbook to establish an estimate of the total number of words. For the instructor slide decks, all decks were provided in Power Point, so we were able to obtain the exact number of words through that software. We then calculated the percentage of stakeholder and sustainability words for each resource. The results of our content analysis are displayed in Table 4 and are quite stark. Even given the shift in industry over the past decade toward stakeholder capitalism (e.g. Fink, 2021), the bulk of the text and instructor slide decks pertain to the shareholder, with little attention paid to other stakeholder groups and furthermore, sustainability. More specifically, terms pertaining to investors dwarf those for other stakeholder groups, with investors covered in 0.1% of the Ross et al. (2019) text, 0.2% of both the Brigham et al. (2017) and Berk et al. (2019) texts, while other stakeholder groups and sustainability topics are collectively represented in less than 0.05% of the texts, for all texts that we assess. The instructor slides provide similar results. These findings provide strong support for the contention that, on average, ESG issues are not being presented in a meaningful way in introductory finance courses. Introductory finance courses commonly provide students with a survey of finance topics (e.g. capital budgeting, asset pricing models, valuation, etc.), which are developed in further depth in advanced level courses. Given the absence of ESG issues within the survey, we suspect there may also be a similar absence in advanced level courses. That said, we do acknowledge that ESG skills may become a specialization for some programs in elective Ross-text (Ross-slides) Total words % Of text Shareholders Table 4. ESG coverage Brigham-text (Brigham-slides) Total words % Of text Berk-text (Berk-slides) Total words % Of text 647 0.094 878 0.193 1,720 142 0.211 266 0.396 1,054 Employees 51 0.007 67 0.015 118 16 0.024 21 0.031 38 Customers 172 0.025 134 0.029 94 27 0.040 29 0.043 82 Communities 2 0.000 5 0.001 5 4 0.006 2 0.003 1 Natural environment 7 0.001 20 0.004 5 6 0.009 10 0.015 15 Government 164 0.024 229 0.050 236 15 0.022 39 0.058 112 Suppliers 93 0.014 75 0.016 105 8 0.012 3 0.004 80 Sustainability 77 0.011 17 0.004 66 8 0.012 3 0.004 19 Note(s): This table displays coverage of ESG terms in textbooks and instructor slide decks 0.223 0.897 0.015 0.032 0.012 0.070 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.013 0.031 0.095 0.014 0.068 0.009 0.016 courses, and even more, instructors may bring these topics into the classroom to complement textbook materials. 4. A pathway forward: SMIFS as a venue for teaching ESG skills Our second research question investigates how business schools can effectively overcome the dearth of ESG-related training in traditional, in-class finance instruction. We propose a nontraditional venue for teaching these skills, one that has become ubiquitous among business schools in North America (Lawrence, 2008): SMIFs [3]. SMIF programs enable students to manage actual investment portfolios, providing students with hands-on investment training (Lawrence, 1990) through experiential learning (Kolb and Fry, 1974). Experiential learning embraces “learning-by-doing” and involves observation and reflection, formation of abstract concepts and testing of those concepts in new situations, with each of these components of equal importance to achieving the ultimate goal of knowledge creation (Kolb, 2014). Business schools have implemented a range of experiential, learner-centric curriculum, including case discussions, technology demonstrations and tutorials, games and interactive assessments (Reynolds and Vince, 2007; Szczerbacki et al., 2000; Dolan and Stevens, 2006). Research (e.g. Bevan and Kipka, 2012) has provided evidence that experiential learning is a highly effective approach to knowledge creation within a variety of fields, such as talent management, leadership capabilities, change management and entrepreneurship. Similarly, research on SMIFs has concluded that this type of pedagogical innovation is an exemplar form of experiential learning as SMIFs facilitate direct application of finance, accounting and economics concepts by students who are making investment decisions that have direct and observable results (Neely and Cooley, 2004; Lawrence, 2008; Dolan and Stevens, 2006; Ammermann et al., 2009; Arena and Krause, 2019). Previous research, for example Charleton et al. (2015) highlights the role of SMIF participation in career success of program alumni, which contributes further evidence that these experiential programs are effective venues for equipping students with industry skills. Moreover, these programs often include industry mentoring (Oldford, 2019; Rajasulochana et al., 2019), which further enriches experiential learning and ensures an authentic learning environment. Given that a SMIF provides a setting for a person’s development of a deep and applied understanding of investment concepts, we propose that a SMIF may serve as an ideal, albeit nontraditional, setting for business schools to quickly adapt to industry’s demand for ESG skills. We contend that a SMIF will be potentially effective in equipping students with ESG skills because these programs are an authentic, applied experiential learning program, which have been showed to be effective in teaching traditional investment skills (Dolan and Stevens, 2006; Arena and Krause, 2019; among others). As a result, we expect that with a robust ESG framework, these programs can also serve as a fruitful setting in which students can acquire ESG skills. Existing research that discusses ESG within SMIF analysis and decision-making is small but growing. Clinebell (2013), Ascioglu et al. (2017), Ascioglu and Maloney (2019), Saunders (2015), Ghosh et al. (2019), and Brune and Files (2019) each discuss how ESG integration into a SMIF has permitted students to achieve risk-adjusted returns, to mitigate risk and to adhere to an ethical consideration within their organizations. Further, Saunders (2015) engages students in the process of attending shareholder meetings and getting students to practice shareholder advocacy and engagement through socially responsible investing (SRI). Clinebell (2013) discusses the importance of SRI in investment education and provides a framework of how it can be included as part of a SMIF program. However, each of these studies also describes how students use ESG rankings or screens to make investment decisions. For example, Ascioglu et al. (2017) discusses how their SMIF, Archway Investment Fund, uses the SMIF and ESG pedagogy 65 MF 48,1 66 Sustainalytics database data for ESG rankings and scores and, to supplement ESG rankings, compares them to benchmarks for industry holdings. While these programs are making progress, the use of rankings and screens described by these studies circumvents the development of a student’s analytical skills related to ESG analysis. In the following, we describe how a typical SMIF can be agile in its integration of ESG-related thinking, in a way that intentionally promotes the development of students’ ESG-related skills, which are of high demand in industry. Based on the experience of a faculty advisor, industry mentors and students, we summarize the purposeful integration of ESG within a Canadian SMIF, showcasing how the ESG framework was developed and implemented [4]. This SMIF’s process of development and resultant framework mimics practice and is simple in nature, and therefore, this experience can serve as a roadmap for other business schools. 4.1 An experiential learning approach to the development of an ESG framework Considering that industry continues to wrestle with how to assess ESG-related opportunities, risks and benchmarks (Napoletano and Curry, 2021), it is evident that the development of an ESG framework within a SMIF would be no small feat. In the following, we describe the experience of a Canadian SMIF that developed and adopted an ESG framework during the 2020–2021 academic year. In the spirit of experiential learning, the SMIF took the approach of truly embedding students in each step of the framework’s development, and a student was assigned the title of “ESG Analyst”. The role of this student involved leading the information gathering process that informed the development of the SMIF’s ESG framework. To launch this project’s development, the ESG analyst spent several weeks researching ESG trends and developing a research briefing that was presented to other students in the program. The presentation spurred constructive debate and served as an opportunity for both peer-to-peer teaching (Kolb, 2014) as well as buy-in for the ESG project. Following implementation, the student ESG analyst led the effort in implementing and supporting the new ESG framework while also assisting other students in their integration of ESG factors into equity research. It is the intention of the SMIF to assign this role to a new senior student each year. Students decided that the next step involved consulting directly with a variety of industry experts to gain greater insight into how to proceed. Leveraging this SMIF’s industry network, as well as university alumni, seminars were scheduled with an ESG consultant, an ESG portfolio manager, a head of sustainable investing at a large pension plan and a director of sustainability at a publicly traded company. These conversations occurred over a one-month period during fall 2020. A working document was created to support this information gathering endeavor, and following each seminar, students and faculty had follow-up discussions and contributed equally to a collaborative working document. In the following, we summarize the key takeaways from each seminar. 4.1.1 ESG consultant. The approach to assessing the value and risk of a company’s ESG profile is highly contingent on a firm’s industry. For example, different issues arise when looking at a company in information technology (more social issues like cyber security) versus energy (more climate related issues like carbon emissions). There are a variety of ways that investment teams are currently integrating ESG: qualitative, quantitative, proprietary check-lists or integration of all these approaches. Common among most teams is the goal of establishing a set of the most financially material ESG issues. To be efficient in this effort, the ESG consultant advised that students rely upon the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) materiality map, a free online resource commonly employed in industry (SASB, 2021). The materiality map allows professionals to quickly drill down to material ESG factors by sub-industry (Wu et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2016). The ESG consultant suggested that students use sustainability rankings (e.g. MSCI ESG Index or Sustainalytics) as a sanity check, but cautioned that they must be aware of how each of these rankings are constructed [5]. Also, the ESG consultant recommended that students try to integrate ESG analysis into each step of equity and portfolio analysis, which will help to avoid boilerplate ESG research. Finally, the ESG consultant recommended that, at least when beginning, students should implement qualitative analysis of ESG factors (e.g. incorporating into investment thesis), saving integration of quantitative analyses (e.g. incorporating into a discount rate for a valuation) for when both industry and the SMIF program has a stronger understanding of how to benchmark ESG performance. 4.1.2 Portfolio manager, ESG mandate. It is essential that students take the perspective that an understanding of ESG will permit a stronger and more holistic assessment of a company. It may be that some hidden aspects of the company are uncovered that might provide better insight and potentially impact future returns. A firm’s investment in ESG can result in positive outcomes for the company; for example, it can help companies avoid litigation or enhance employee retention through better or safer working environments. An important challenge is disclosure of ESG-related information. While many companies have been disclosing ESG factors for some time now, others still choose not to disclose. It is important that students also evaluate nondisclosure of material ESG factors. However, across industries, disclosure norms and requirements are still in development, making benchmarking quite challenging. Similar to the ESG consultant, the portfolio manager was suggested that students consider using the SASB materiality map for identifying material ESG factors, but cautioned that students be critical of the factors as there is company-level variability in materiality. Again, similar to the ESG consultant, the portfolio manager advised that students should not take sustainability rankings at face value, noting that much of the data are self-reported. A final piece of advice was that students should attempt to drill down to the ESG factor that will limit the company’s growth and integrate this factor into the investment thesis and valuation, if possible. 4.1.3 Director of sustainability, publicly listed company. More and more, companies are trying to craft a narrative that communicates their ESG strategy, risks and opportunities, and furthermore, conversations with investors are increasingly dominated by ESG issues. As a result, companies are being pushed for more and more disclosure, even if there is no standard for disclosure. Some companies are taking their own initiative to establish goals and benchmarks for reporting of material ESG issues. Similar to the portfolio manager with an ESG mandate, the director of sustainability advised that students pay attention to nondisclosure as a negative indicator. Companies pay careful attention to sustainability rankings and work hard to improve scores, so students should avoid relying solely on rankings. The director of sustainability suggested that students actively engage in questioning companies on ESG factors, connecting directly with investor relations departments. 4.1.4 Head of sustainable investing, large pension plan. This organization takes the view that companies that perform well on ESG will perform better in the long-run. Further, they view companies themselves versus regulators as best suited to be able to achieve progress on ESG. For public equities, they construct an ESG report that incorporates any publicly available information, marketing materials, risk section of financial statements, investments on the horizon, corporate reputation and external sustainability rankings and reports. The ESG report establishes their view of risks and opportunities. Because there is a lack of reliable data, they are using these reports and other research to develop an internal database that helps guide risk assessment and benchmarking. The head of sustainable investing noted that while qualitative assessment of ESG factors is feasible, it is challenging to accurately quantify these factors, so the head of sustainable investing suggested that students focus on qualitative analysis. Similar to others, the head of sustainable investing advised that students consult and integrate the SASB framework to determine 3–4 factors that are most material, as SMIF and ESG pedagogy 67 MF 48,1 68 a starting point for ESG analyses. The head of sustainable investing also suggested that students work hard to incorporate ESG analysis into each step of their research. In addition, students should regularly scan the ESG landscape to understand any new developments, continuously adjusting the framework as the space evolves. 4.2 The framework Following consultations with industry and a number of follow-up discussions, the students developed a simple ESG framework, a process that was supported by a faculty advisor. As a first step, the students developed a guiding ESG mission statement, which included four elements: (1) incorporate ESG-related risks and opportunities into equity and portfolio analyses, (2) develop students’ ability to assess and practically evaluate ESG factors, (3) engage students in responsible and sustainable investing to evoke positive global change and shape better global citizens and (4) achieve sustainable returns on investments. A goal of the ESG framework to encourage students to adopt an ESG lens when approaching the SMIF’s existing investment process, which includes forming sector teams, stock picking, in-depth equity research and presentation of a stock pitch. After several iterations, the students established the ESG framework summarized in Figure 1, which involves four steps: (1) Step 1 – Identify industry materiality: The first step is to determine and understand the material ESG factors in the selected industry. For this program, students first assess the industry (or sometimes sector) prior to stock picking. This step involves identifying the industry’s key ESG trends, risks and opportunities. Following the advice of industry experts, the framework largely relies upon the SASB materiality map [6] (SASB, 2021), though students are encouraged to investigate elements outside of this map by researching press releases, analyst coverage and news events. At this stage, the student should also consult ESG rankings to obtain a sense of the ESG landscape within the industry. This research is then incorporated into the student’s stock selection, along with other factors, including financial performance and portfolio fit. This step ensures that ESG factors are considered early in the equity research process and play a role in stock selection. (2) Step 2 – Identify equity-level materiality: After the student has selected a stock, the second step in the ESG framework is to identify the most relevant ESG risks and opportunities that directly pertain to the equity. Working with the student ESG analyst, the student investigates material, industry-level ESG factors from Step 1 but now, in the context of the company, with the aim of establishing 3–4 company-specific material ESG factors. This research involves an examination of a company’s current and past operations, as well as the company’s current ESG strategy, with particular attention paid to the degree of information disclosure. The student may also analyze the company’s ESG reports, strategic plans, company filings, company news events, on-book ESG investment, financial statements, notes to the financial statements and analyst coverage. This step affords the student a deep understanding of companyspecific ESG performance while actively avoiding industry stereotypes. Figure 1. ESG framework (3) Step 3 – Assess material, company ESG factors: Once a list of material ESG factors is established, the student then provides a thorough qualitative assessment of the ESG factors to determine if and how these factors might positively or negatively affect the company’s future. If positive, the student assesses the stability of this opportunity, and if negative, the student assesses the permanency or mitigation plans for this risk. This is a challenging endeavor as the investment industry is still moving toward standardized disclosure and benchmarking practices; however, students are encouraged to examine the material factors alongside past performance and industry competitors. (4) Step 4 – Integrate into equity research: The final step in this framework involves deciding how to integrate ESG factors into a student’s stock pitch. The student works with the ESG Analyst to make this decision, and the decision is guided by the knowledge generated in the first three steps of this framework. First, the student is encouraged to consider if the ESG factor is an element of the investment thesis. Otherwise, the factors may be incorporated into the competitive analysis or other elements of the stock pitch. Upon implementation of this framework, all students are expected to incorporate ESG factors into their final stock pitch, but the positioning of ESG within their research is ultimately determined by the student. Students are encouraged to employ a qualitative assessment of ESG factors, but if a student is eager to attempt quantification, they will be encouraged to do so. Following the stock pitch (which, at this particular SMIF, is presented verbally to the student investment team and industry mentors), the students discuss the merits of the stock pitch, including the merits of the ESG-related argument. In this way, the student receives direct peer and industry feedback on ESG-related research, and this feedback is integral to effective experiential learning. In addition, the student works alongside peers throughout the development of the ESG research, which further contributes to a deep understanding of ESG. Taken together, this framework is a simple point of departure for business schools to effectively equip students with ESG analytical and technical skills, thereby quickly responding to industry demand. 4.3 Pedagogical implications Prior to introducing ESG analysis into the program, the students’ equity research involved a flexible template of topics: corporate governance, competitive analysis, industry analysis, 2–4 investment theses and equity valuation (e.g. discounted cash flow, relative and related transactions). With the introduction of the ESG framework, the demand on students expanded since now each stock pitch required some form of integration of ESG issues. As mentioned in the previous section, the ESG framework employed at this SMIF does not have a uniform placement within students’ equity research so as to avoid boilerplate analysis. Instead, the framework, guided by the program’s ESG philosophy (outlined in Section 4.2), encourages students to employ an ESG lens to each step in their analysis, from industry analysis to stock picking to the construction of their investment theses. The implementation of the ESG framework did and will continue to require dedicated instructional time and continuous research and learning, particularly since ESG is an evolving space. At this SMIF, this is not accomplished by replacing other topics or issues discussed. Instead, additional seminars, whether student-led, faculty-led or industry-led, have been introduced to support learning. As a result, the number of total seminars has increased by approximately 10%, which can be accomplished as there is no traditional lecture for this program. In addition, the program’s industry mentors, having been involved in the development of the ESG framework along with being involved in the industry’s ESG movement, consistently question students on their ESG analyses and assumptions, which SMIF and ESG pedagogy 69 MF 48,1 70 provide for further learning as student defend their work. The process of applied feedback to applied research is a pillar of Kolb’s (2014) experiential learning cycle. 4.4 Assessing effectiveness of the ESG framework Evidence from a variety of disciplines (for example, in geography (Healey and Jenkins, 2000), in nursing (Hill, 2017) and architecture (Rodriguez, 2018)) underscores the effectiveness of experiential learning programs in equipping students with practical skills. Similarly, evidence from business schools (e.g. Mallett et al., 2010) shows that SMIFs are an effective training ground for students entering the investment industry. Therefore, a SMIF, an experiential learning program, may provide the ideal setting for teaching ESG skills since, as we show, these seem to have little presence within traditional lecture-style venues. The ESG framework proposed in this paper was implemented in January 2021, and students were encouraged to embed ESG analyses into their stock pitches since then. As a result, students are still in the process of developing ESG-related skills, and it is, therefore, difficult to assess the effectiveness of the program in developing these skills. However, we collected anecdotal evidence from the faculty advisor, an industry mentor and several students (including the student ESG Analyst), all of which point to early progress in ESG skills development. The following are excerpts from solicited feedback: Faculty advisor: “Since introducing the framework, each stock pitch clearly demonstrated integration of ESG, mainly through an analysis of ESG risks. I can see a depth of analysis on these issues that suggests a strong understanding of how ESG is related to stock price. Often students displayed an overreliance on information disclosed by the company, which can be skewed. I will continue to encourage critical analysis of ESG data, and I will also encourage students to consider how a company’s ESG factors may present an opportunity that may be overlooked by the market.” Industry mentor: “This is a great start, I love to see students dig into these ESG issues that we are also struggling with in the work I do. In my opinion, the research I’ve seen on ESG so far puts these students at a major advantage when they head to industry. From my own experience, I’m having a hard time finding people who can do this stuff, so knowing that newcomers will have some taste of ESG is terrific. Looking forward to seeing how these students keep up with the evolving ESG landscape.” Student ESG Analyst: “To adequately address ESG factors in equity analysis, the investor must have a deep understanding of the company’s operations and how management chooses to conduct business. Understanding how and why companies make business decisions will ultimately lead you to understand how the company is or is not properly addressing the ESG factors most relevant to their operations. Addressing the ESG factors at the root allows the investor to identify what ESG factor means to the business and ultimately what impact they will have on expected returns.” Student Analyst: “The skill I have learned from applying the ESG framework is how to analyze an equity with ESG at mind. It is critical to consider ESG as we need understand the environment the company operates in and their related pressure points. I embedded the ESG analysis into my equity research by using it as a screening tool to ensure the company I would pitch would be compliant to ESG issues and to understand exactly what types of ESG risks the company is exposed to.” Student Analyst: “Especially when selecting an equity to pitch, I used ESG measures to narrow the search and select a company. While creating my pitch, I tried to find how ESG trends fit into my investment thesis. I learned that ESG factors might not often be directly used to increase profit but when used in conjunction with the right business practice, they can add value. Simply being aware of ESG risks (materiality map) and thinking about how positive ESG practices may impact a business have affected the way I think about investing.” Student: “I was able to learn about the SASB ESG map and was able to find elements of my company that I would not have thought about otherwise. I learned much more about the importance of a proactive ESG plan instead of a reactive plan. It was also interesting to look at the ESG of my company versus their competitors and see where they sit as a leader or follower.” 5. Conclusions With industry’s increasing emphasis on sustainable business practices and accordant ESG factors, those in and entering the investment industry require a new set of analytical skills to support the changing landscape. The industry, however, is challenged with finding people with the necessary ESG-related skills, and in this paper, we examine this skills gap from the perspective of training within undergraduate business school programs. We find that traditional pedagogy (i.e. lectures and textbooks) provide a limited coverage of ESG topics, and given that traditional teaching methods are slow to adapt, we propose an alternative setting, SMIFs, where ESG skills can be acquired in way that is effective and applied while also being integrated swiftly. Using a case study of an existing SMIF, we show how these powerful experiential learning programs can integrate real-world ESG analysis, thereby equipping students, who will soon join the investment industry, with skills that will contribute to closing the industry’s skills gap. Notes 1. We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this possible explanation. 2. See for example, Financial Times’ coverage of how the Rotterdam School of Management has incorporated a greater focus on social good (Jack, 2019). 3. For a review of the SMIF literature, see Abukari et al. (2021). 4. This SMIF follows the traditional design of a student managed investment fund, as summarized by Abukari et al. (2021). It primarily invests in North American equity markets with a value mandate; students operate in sector teams and take a bottom-up approach to stock selection; the student team is constructed annually from September to August; its investments are guided by an investment charter; it is funded by donations; and the program is supported by faculty members and industry mentors. 5. The MSCI ESG Index is designed to measure the performance of common ESG investment strategies by re-weighting or excluding companies through their ESG criteria (MSCI, 2021), while Sustainalytics seeks to measure a company’s exposure to industry specific ESG risks and how effectively a company manages and addresses those risks (Sustainalytics, 2021). 6. To access the materiality map, see: https://materiality.sasb.org/ References AACSB (2020), “Guiding principles and standards for business accreditation”, available at: https:// www.aacsb.edu/-/media/aacsb/docs/accreditation/business/standards-and-tables/2020 business accreditation standards.ashx?la5en&hash5E4B7D8348A6860B3AA9804567F02C68960 281DA2 (accessed 21 May 2021). Abukari, K., Oldford, E. and Willcott, N. (2021), “Student-managed investment funds: a review and research agenda”, Managerial Finance. doi: 10.1108/MF-02-2021-0080. Accounting for Sustainability (2019), “A4S summit 2019”, Event Report, available at: https://www. accountingforsustainability.org/content/dam/a4s/corporate/media/Event Report Summit 2019 cover.pdf.downloadasset.pdf (accessed 9 March 2021). Akrivou, K. and Bradbury-Huang, H. (2015), “Educating integrated catalysts: transforming business schools toward ethics and sustainability”, Academy of Management Learning and Education, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 222-240, doi: 10.5465/amle.2012.0343. SMIF and ESG pedagogy 71 MF 48,1 Alsayegh, M.F., Abdul Rahman, R. and Homayoun, S. (2020), “Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure”, Sustainability, Vol. 12 No. 9, pp. 1-20, doi: 10.3390/su12093910. Amel-Zadeh, A. and Serafeim, G. (2018), “Why and how investors use ESG information: evidence from a global survey”, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 74 No. 3, pp. 87-103, doi: 10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2. 72 Amenc, N., Christiansen, E., Esakia, M. and Goltz, F. (2020), ESG Engagement and Divestment: Mutually Exclusive or Mutually Reinforcing, Scientific Beta Publication, available at: https://www.globenews wire.com/Tracker?data54TNd3tk_f_yavIHi3TGvqlwQkd25OB1SBYCjY3rEp9nUFaLaLLO 120gP5XoL83kI1tPkel38GsYonFZkEg1-vuMH17ZPWMMqaz2D5wjaiEwy4BT0AodiIX_ r1Nh95JA0uS71sZ7lyyINcPtRgKiyfZcHBEigXXh0RCBzXveSRwP0qEQ_tde1dlBATfgTU5 67mzpuJbMGf1nLde5A7JUTaRpJPbxrGugnGGwo9gveK3c (accessed 3 June 2021). Ammermann, P., Gupta, P. and Ma, Y. (2019), “The learning experience continues: two decades and counting for CSULB’s SMIF program”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 46 No. 4, pp. 513-529, doi: 10. 1108/MF-10-2018-0481. Arabella Advisors (2018), “The global fossil fuel divestment and clean energy investment movement – 2018 report”, available at: https://www.arabellaadvisors.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ Global-Divestment-Report-2018.pdf (accessed 11 May 2021). Arena, M. and Krause, D.K. (2019), “How to develop successful and ethical investment analysts”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 46 No. 5, pp. 590-598, doi: 10.1108/MF-08-2018-0404. Ascioglu, A., Saatcioglu, K. and Smith, A. (2017), “Integration of ESG metrics into a student-managed fund: creating sustainable student-managed funds”, The Journal of Trading, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 59-71, doi: 10.3905/jot.2018.13.1.059. Ascioglu, A. and Maloney, K.J. (2019), “From stock selection to multi-asset investment management”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 46 No. 5, pp. 647-661, doi: 10.1108/MF-07-2018-0304. Ashwin Kumar, N.C., Smith, C., Badis, L., Wang, N., Ambrosy, P. and Tavares, R. (2016), “ESG factors and risk-adjusted performance: a new quantitative model”, Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 292-300, doi: 10.1080/20430795.2016.1234909. Berk, J., DeMarzo, P. and Stangeland, D. (2019), Corporate Finance, 4th Canadian ed., Pearson Canada, North York. Berry, T., Cook, L. and Stevens, K. (2010), “An exploratory analysis of textbook usage and study habits: misperceptions and barriers to success”, College Teaching, Vol. 59 No. 1, pp. 31-39, doi: 10.1080/87567555.2010.509376. Bevan, D. and Kipka, C. (2012), “Experiential learning and management education”, The Journal of Management Development, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 193-197, doi: 10.1108/02621711211208943. Brigham, E.F., Ehrhardt, M.C., Gessaroli, J. and Nason, R.R. (2017), Financial Management: Theory and Practice, 3rd Canadian ed., Nelson Education, Toronto. Brogi, M. and Lagasio, V. (2019), “Environmental, social, and governance and company profitability: are financial intermediaries different?”, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 576-587, doi: 10.1002/csr.1704. Brune, C. and Files, J. (2019), “Biblical screens and the stock selection process: applications for a student-managed fund”, Christian Business Academy Review, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 87-90, available at: https://cbfa-cbar.org/index.php/cbar/article/view/510. Business Roundtable (2019), “Business roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote ‘an economy that serves all Americans’”, available at: https://www.businessroundtable.org/ business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-servesall-americans (accessed 7 January 2021). CFA Institute (2020), “Future of sustainability in investment management”, available at: https://www. cfainstitute.org/en/research/survey-reports/future-of-sustainability (accessed 20 January 2021). CFA Institute (2021), “ESG investing and analysis”, available at: https://www.cfainstitute.org/en/ research/esg-investing (accessed 23 July 2021). Charlton, W.T. Jr, Earl, J. and Stevens, J.J. (2015), “Expanding management in student managed investment funds”, Journal of Financial Education, Vol. 41 No. 2, pp. 1-23, available at: https:// www.jstor.org/stable/24573676. SMIF and ESG pedagogy Cheng, B., Ioannou, I. and Serafeim, G. (2014), “Corporate social responsibility and access to finance”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 1-23, doi: 10.1002/smj.2131. Clinebell, J. (2013), “Socially responsible investing and student managed investment funds: expanding investment education”, Financial Services Review, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 13-22. Crilly, D. and Ioannou, I. (2017), Talk is not Always Cheap: what Firms Say, How They Say it, and Social Performance, Working paper, London Business School, available at: https://papers.ssrn. com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id52417987. Delmas, M.A. and Burbano, V.C. (2011), “The drivers of greenwashing”, California Management Review, Vol. 54 No. 1, pp. 64-87, doi: 10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64. Dhaliwal, D.S., Li, O.Z., Tsang, A. and Yang, Y.G. (2011), “Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: the initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 86 No. 1, pp. 59-100, doi: 10.2308/accr.00000005. Dinapoli, J. (2021), “PwC planning to hire 100,000 over five years in major ESG push. Reuters”, available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/pwc-planning-hire-100000over-five-years-major-esg-push-2021-06-15/ (accessed 17 June 2021). Dolan, R.C. and Stevens, J.L. (2006), “Business conditions and economic analysis: an experiential learning program for economics students”, The Journal of Economic Education, Vol. 37 No. 4, pp. 395-405, doi: 10.3200/JECE.37.4.395-405. Eccles, R.G., Kastrapeli, M.D. and Potter, S.J. (2017), “How to integrate ESG into investment decisionmaking: results of a global survey of institutional investors”, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 125-133, doi: 10.1111/jacf.12267. El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C.C. and Mishra, D.R. (2011), “Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital?”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 35 No. 9, pp. 2388-2406, doi: 10. 1016/j.jbankfin.2011.02.007. Fatemi, A.M. and Fooladi, I.J. (2013), “Sustainable finance: a new paradigm”, Global Finance Journal, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 101-113, doi: 10.1016/j.gfj.2013.07.006. Fatemi, A., Glaum, M. and Kaiser, S. (2018), “ESG performance and firm value: the moderating role of disclosure”, Global Finance Journal, Vol. 38, pp. 45-64, doi: 10.1016/j.gfj.2017.03.001. Fink, L. (2020), “Annual letter to CEOs”, available at: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investorrelations/larry-fink-ceo-letter (accessed 29 April 2020). Fink, L. (2021), “Annual letter to CEOs”, available at: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investorrelations/larry-fink-ceo-letter (accessed 6 May 2021). Fiset, J., Oldford, E. and Chu, S. (2021), “Market signaling capacity of written and visual charismatic leadership tactics”, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, Vol. 29, doi: 10.1016/j.jbef. 2021.100465. Flammer, C. (2015), “Does corporate social responsibility lead to superior financial performance? A regression discontinuity approach”, Management Science, Vol. 61 No. 11, pp. 2549-2568, doi: 10. 1287/mnsc.2014.2038. Freeman, E. and Liedtka, J. (1997), “Stakeholder capitalism and the value chain”, European Management Journal, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 286-296, doi: 10.1016/S0263-2373(97)00008-X. Friede, G., Busch, T. and Bassen, A. (2015), “ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies”, Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 210-233, doi: 10.1080/20430795.2015.1118917. Friedman, M. (1970), The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits, Ney York Times Magazine, p. 17, available at: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1970/09/13/ 223535702.html. 73 MF 48,1 74 Gardner, B. (2015), “The cost of inaction: recognising the value at risk from climate change”, The Economist, available at: https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/sustainability/cost-inaction (accessed 20 August 2019). Gencsu, I. and Mason, N. (2018), “Unlocking the inclusive growth story of the 21st century: accelerating climate action in urgent times”, ODI, available at: https://odi.org/en/publications/ unlocking-the-inclusive-growth-story-of-the-21st-century-accelerating-climate-action-in-urgenttimes/ (accessed 17 January 2021). Ghosh, C., Gilson, P. and Rakotomavo, M. (2019), “Student managed fund (SMF) at the University of Connecticut”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 46 No. 4, pp. 548-564, doi: 10.1108/MF-09-2018-0426. Gitsham, M. and Clark, T.S. (2014), “Market demand for sustainability in management education”, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 291-303, doi: 10. 1108/IJSHE-12-2011-0082. Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2018), “Global sustainable investment review”, available at: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GSIR_Review2018.3.28.pdf (accessed 11 May 2021). Glossner, S. (2018), “ESG incidents and shareholder value”, available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/ papers.cfm?abstract_id53004689. Goldman Sachs (2017), “The metrics that matter – a ‘mainstream’ approach to ESG”, Exchanges at Goldman Sachs, available at: https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/podcasts/episodes/05-082017-derek-bingham.html (accessed 22 April 2021). Grewal, J., Hauptmann, C. and Serafeim, G. (2020), “Material sustainability information and stock price informativeness”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 171, pp. 513-544, doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04451-2. Hauptmann, C. (2017), “Corporate sustainability performance and bank loan pricing: it pays to be good, but only when banks are too”, Saı€d Business School Working Paper, available at: https:// papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id53067422 (accessed 15 May 2021). Healey, M. and Jenkins, A. (2000), “Kolb’s experiential learning theory and its application in geography in higher education”, Journal of Geography, Vol. 99 No. 5, pp. 185-195, doi: 10.1080/ 00221340008978967. Henisz, W., Koller, T. and Nuttall, R. (2019), “Five ways that ESG creates value”, available at: http:// dln.jaipuria.ac.in:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/2319/1/Five-ways-that-ESG-creates-value.pdf. Hill, B. (2017), “Research into experiential learning in nurse education”, British Journal of Nursing, Vol. 26 No. 16, pp. 932-938, doi: 10.12968/bjon.2017.26.16.932. Hunt, V., Simpson, B. and Yamada, Y. (2020), “The case for stakeholder capitalism”, McKinsey, available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/ourinsights/the-case-for-stakeholder-capitalism (accessed 20 July 2021). Ielasi, F., Ceccherini, P. and Zito, P. (2020), “Integrating ESG analysis into smart beta strategies”, Sustainability, Vol. 12 No. 22, pp. 1-22, doi: 10.3390/su12229351. Jack, A. (2019), “Business schools shift to a more sustainable future”, Financial Times, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/72d094ac-cf25-11e9-b018-ca4456540ea6 (accessed 7 December 2020). Khan, M., Serafeim, G. and Yoon, A. (2016), “Corporate sustainability: first evidence on materiality”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 91 No. 6, pp. 1697-1724, doi: 10.2308/accr-51383. Kolb, D.A. (2014), Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, FT Press, NJ. Kolb, D.A. and Fry, R.E. (1974), Toward an Applied Theory of Experiential Learning, MIT Alfred P. Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA. Kothari, S.P., Li, X. and Short, J.E. (2009), “The effect of disclosures by management, analysts, and business press on cost of capital, return volatility, and analyst forecasts: a study using content analysis”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 84 No. 5, pp. 1639-1670, doi: 10.2308/accr.2009.84.5.1639. Krippendorff, K. (2018), Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. Lawrence, E.C. (1990), “Learning portfolio management by experience: university student investment funds”, Financial Review, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 165-173, doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6288.1990.tb01295.x. Lawrence, E.C. (2008), “Student managed investment funds: an international perspective”, Journal of Applied Finance (Formerly Financial Practice and Education), Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 1-17, available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract52698650. Liu, J. (2021), “ESG investing comes of age”, Morningstar, available at: https://www.morningstar.com/ features/esg-investing-history (accessed 21 June 2021). Mallett, J.E., Belcher, L.J. and Boyd, G.M. (2010), “Experiment no more: the long-term effectiveness of a student-managed investments program”, Journal of Financial Education, Vol. 36 Nos 3-4, pp. 1-15, available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41948644. Minh, T.C. (2021), Widespread ‘competence Greenwashing’ Threatens to Derail Progress in Sustainable Finance, Changing America, The Hill, available at: https://thehill.com/changing-america/ sustainability/environment/560255-widespread-competence-greenwashing-threatens-to. Morbiato, A. (2021), “The ESG movement”, Invenicement, available at: https://www.invenicement.com/ uncategorized/the-esg-movement/. MSCI (2021), “ESG indexes”, available at: https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esgindexes. Muff, K. (2012), “Are business schools doing their job?”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 31 No. 7, pp. 648-662, doi: 10.1108/02621711211243854. Murray, S. (2020), “ESG investing cries out for trained finance professionals”, Financial Times, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/d92a89ec-740c-11ea-90ce-5fb6c07a27f2 (accessed 19 June 2021). Nagy, Z., Kassam, A. and Lee, L.E. (2016), “Can ESG add alpha? An analysis of ESG tilt and momentum strategies”, The Journal of Investing, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 113-124, doi: 10.3905/joi.2016. 25.2.113. Napoletano, E. and Curry, B. (2021), “Environmental, social, and governance: what is ESG investing?”, Forbes Advisor, available at: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/esg-investing/ (accessed 22 June 2021). Neely, W.P. and Cooley, P.L. (2004), “A survey of student managed funds”, Advances in Financial Education, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 1-9. Oldford, E. (2019), “Confessions of a faculty advisor: development of a student managed investment fund program under constraints”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 46 No. 4, pp. 576-586, doi: 10.1108/ MF-08-2018-0390. Porter, M.E. (1991), “America’s green strategy”, Scientific American, Vol. 264 No. 4, p. 168. Pronina, L. and Rocha, P. (2021), “ESG skills are a hot item on today’s resumes”, Bloomberg Investing, available at: https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/esg-skills-are-a-hot-item-on-today-s-resumes-1. 1606678 (accessed 28 June 2021). PWC (2019), “Creating a strategy for a better world”, available at: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/ sustainability/SDG/sdg-2019.pdf (accessed 27 June 2021). Raelin, J.A. (2009), “The practice turn-away: forty years of spoon-feeding in management education”, Management Learning, Vol. 40 No. 4, pp. 401-410, doi: 10.1177/1350507609335850. Rajasulochana, S.R., Heggede, S. and Jadhav, A.M. (2019), “Student-managed investment course: a learner-centric approach to investment management”, Cogent Economics and Finance, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 1-23, doi: 10.1080/23322039.2019.1699390. Ransome, J. and Newton, P.M. (2018), “Are we educating educators about academic integrity? A study of UK higher education textbooks”, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, Vol. 43 No. 1, pp. 126-137, doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1300636. SMIF and ESG pedagogy 75 MF 48,1 RBC Global Asset Management (2021), “ESG and shareholder value”, available at: https://global. rbcgam.com/sitefiles/live/documents/pdf/whitepapers/eue_esg-and-shareholder-value.pdf. Responsible Investment Association Canada (2020), “Canadian RI trends report”, available at: https:// www.riacanada.ca/research/2020-canadian-ri-trends-report/ (accessed 15 May 2021). Reynolds, M. and Vince, R. (2007), Handbook of Experiential Learning and Management Education, Oxford University Press, New York. 76 Rodriguez, C.M. (2018), “A method for experiential learning and significant learning in architectural education via live projects”, Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 279-304, doi: 10.1177/1474022217711878. Ross, S.A., Westerfield, R.W., Jordan, B.D., Roberts, G.S., Pandes, J.A. and Holloway, T.A. (2019), Fundamentals of Corporate Finance, 10th Canadian ed., McGraw Hill Education. SASB (2021), “Materiality map”, available at: https://www.sasb.org/standards/materiality-map/ (accessed 2 October 2020). Saunders, K.T. (2015), “Experiential learning: shareholder engagement in a student managed investment fund”, Christian Business Academy Review, Vol. 10, pp. 45-54, available at: https:// www.cbfa-cbar.org/index.php/cbar/article/view/19. Schlegelmilch, B.B. (2020), “Why business schools need radical innovations: drivers and development trajectories”, Journal of Marketing Education, Vol. 42 No. 2, pp. 93-107, doi: 10.1177/ 0273475320922285. Schumacher, K. (2020), “‘Competence greenwashing’ could be the next risk for the ESG industry”, Responsible Investor, available at: https://www.responsible-investor.com/articles/competencegreenwashing-could-be-the-next-risk-for-the-esg-industry. Schwab, K. (2019), Why we Need the ‘Davos Manifesto’ for a Better Kind of Capitalism, World Economic Forum, available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/why-we-need-thedavos-manifesto-for-better-kind-of-capitalism/ (accessed 2 December 2020). Seto-Pamies, D. and Papaoikonomou, E. (2016), “A multi-level perspective for the integration of ethics, corporate social responsibility and sustainability (ECSRS) in management education”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 136 No. 3, pp. 523-538, doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2535-7. SNEU (2021), “Dr. Kim Schumacher on ESG competence greenwashing: ‘We should not equate awareness or passion with subject matter expertise’”, available at: https://sustainabilitynews. eu/dr-kim-schumacher-on-esg-competence-greenwashing-we-should-not-equate-awareness-orpassion-with-subject-matter-expertise/. Stern, N. (2007), The Economics of Climate Change: the Stern Review, Cambridge University Press, London. Stiglitz, J. (2019), “Is stakeholder capitalism really back?”, Ideas and Insights, available at: https:// www8.gsb.columbia.edu/articles/chazen-global-insights/stakeholder-capitalism-really-back (accessed 16 February 2021). Sundheim, D. and Starr, K. (2020), “Making stakeholder capitalism a reality”, Harvard Business Review, available at: https://hbr.org/2020/01/making-stakeholder-capitalism-a-reality (accessed 9 June 2021). Sustainalytics (2021), “A consistent approach to assess material ESG risk”, available at: https://www. sustainalytics.com/esg-data. Szabo, S. and Webster, J. (2020), “Perceived greenwashing: the effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 171, pp. 719-739, doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0. Szczerbacki, D., Duserick, F., Rummel, A., Howard, J. and Viggiani, F. (2000), “Active learning in a professional undergraduate curriculum”, Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Vol. 27, pp. 272-278, available at: https://absel-ojs-ttu.tdl.org/absel/index.php/absel/ article/view/915. Walck, C. (2009), “Integrating sustainability into management education: a dean’s perspective”, Journal of Management Education, Vol. 33 No. 3, pp. 384-390, doi: 10.1177/1052562908323091. Wu, Y.C.J., Huang, S., Kuo, L. and Wu, W.H. (2010), “Management education for sustainability: a webbased content analysis”, Academy of Management Learning and Education, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 520-531, doi: 10.5465/amle.9.3.zqr520. Wu, S.R., Shao, C. and Chen, J. (2018), “Approaches on the screening methods for materiality in sustainability reporting”, Sustainability, Vol. 10 No. 9, pp. 1-16, doi: 10.3390/su10093233. Yerushalmy, M. (2014), “Challenging the authoritarian role of textbooks”, International Conference on Mathematics Textbook Research and Development 2014 (ICMT-2014), July 29-31, 2014, UK, University of Southampton, available at: https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/52864348/A_ comparative_analysis_of_national_curricula_relating_to_fractions_in_England_and_Taiwan. pdf#page530. Corresponding author Erin Oldford can be contacted at: eoldford@mun.ca For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com SMIF and ESG pedagogy 77