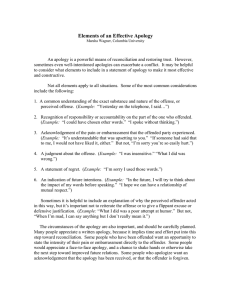

1 HOW SINCERITY AFFECTS FORGIVENESS To Forgive, or Not to Forgive: How the Sincerity of Apologies Online Affect Forgiveness Jane Doe Florida International University 2 HOW SINCERITY AFFECTS FORGIVENESS To Forgive, or Not to Forgive: How the Sincerity of Apologies Online Affect Forgiveness Everybody makes mistakes. From mundane situations such as accidentally grabbing someone else’s lunch to more unique incidents like breaking mom’s favorite vase. While they are not limited to mistakes, an expected apology follows transgressions by recognizing responsibility, consequences, and emotions. Apologies are a two-way street, with the transgressor apologizing and the victim(s) receiving the apology and potentially forgiving the transgressor. However, this act of communication and hopeful mitigation can be driven by numerous emotions that affect its delivery and impression (Hareli & Eisikovits, 2006). Equivalently, the decision on whether that apology should be accepted and forgiven by the recipient is also a product of multiple influences, including type of apology and offense removal (Zeichmeister et al., 2004). A novel factor is the environment, specifically the online environment of the internet and social media platforms. Thus, our study is fixated on analyzing how favorable participants find apologies with varying levels of sincerity (i.e. sincere or insincere) presented on the social network system Twitter, as well as apologies compared to receiving no apology at all. Overall, the study seeks to reveal how the manner in which a transgressor apologizes affects their self-image and perception of the apology. Even apologies serve a purpose, which is namely to restore relationships between the transgressor and the audience and to repair images of an individual’s self as perceived by others at a social value, otherwise known as efforts to save “face” (Hareli & Eisikovits, 2006; Hu et al., 2019; Matley, 2018). Media figures, such as celebrities and politicians, often engage in apologizing as a strategy to maintain a positive image in the eyes of the public after causing a transgression that defies norms (Hu et al., 2019). Self-presentation, or “face” on social media, has been found to demonstrate a positivity bias, where positive forms of self-presentation defined 3 HOW SINCERITY AFFECTS FORGIVENESS by norms within an online environment are favorable compared to negative forms (norm defying) (Matley, 2018). Positive self-presentation aims to form a positive impression, such as a photo of a date one planned out for their partner, while negative self-presentation may risk ruining that impression by expressing socially undesirable behavior such as hateful comments. This “saving face” factor encourages apologizing after transgressions to cancel out the offense that damages an individual’s image and reputation, and thus regain that positive self. Additional components that comprise an apology are the emotions in which the transgressor elicits the apology from. These social emotions are key in the process between relationships, as delivery can affect how the message is received. In a study by Hareli and Eisikovits (2006), participants were asked to envision being insulted and getting their feelings hurt by a friend. When the participants were provided with an apology from this friend later on, each apology included the same phrase but differed in cause of the apology mentioned. The causes were stated to be either of the social emotions: guilt, shame, or pity, as well as combinations of two or all three. The apology was then rated in terms of forgiveness and anger toward that friend. The findings suggest that when guilt and shame were stated as the cause for the apology, ratings of forgiveness were higher. However, expressing pity decreased the participant’s forgiveness and increased anger towards the transgressor. The participants perceived apologies motivated by guilt and shame as sincere, although guilt was considered more sincere than shame when comparing an apology driven by guilt and shame to those driven solely by guilt (Hareli & Eisikovits, 2006). Perception of sincerity within the apology and forgiveness had a strong positive correlation, suggesting that the social emotions (i.e. guilt and shame) may serve as an indicator for perceived sincerity of apologies, and thus impact whether the transgressor will be forgiven or not (Hareli & Eisikovits, 2006). This highlights that the 4 HOW SINCERITY AFFECTS FORGIVENESS perception of an apology, not just the apology itself, is the true indicator in whether a relationship has successfully been mended or if the transgressor’s public image has been cleansed. Similar, in a study performed by Zechmeister et al. (2004), participants would perceive apologies distinctively by the presence or absence of certain components. Participants considered apologies insincere when the transgressor apologized, but did not remove the offense, and considered apologies sincere when the transgressor apologized, removed offense, and augmented an effort to make amends. Accordingly, the insincere apologies were the least forgivable, and the sincere apologies were more likely to be forgiven (Zechmeister et al., 2004). The exchange of an apology and forgiveness is extremely complex beyond the surface, and it is more difficult considering the two parties involved might not be on the same page. Further research by Leunissen et al. (2013) observed and found that guilt mediates the perpetrator’s willingness to apologize depending on the intentions behind the transgression. Perpetrators preferred to apologize for an unintentional transgression more so than intentional ones. A disparity existed between perpetrators and victims, where perpetrators are more likely to admit following a transgression if it was unintentional, but victims were more likely to expect an apology when the transgression is intentional. A victim’s need for an apology is mediated, instead, by anger (Leunissen et al., 2013). Additionally, Kirchhoff et al. (2012) conducted research on the relevancy of verbal components within an apology and how it relates to forgiveness. Leunissen et al. (2013) propose that the apology mismatch can function as an index for whether perpetrators are forgiven. The findings suggest that an apology is predicted more so by the perpetrator’s needs and, as such, are forgiven more when they apologize (Leunissen et al., 2013). Thus, the transgressor’s higher need to apologize after unintentional transgressions promotes its probability of being forgiven compared to intentional transgressions. 5 HOW SINCERITY AFFECTS FORGIVENESS Considering the elaborate process of apologies known thus far—how function and feelings affect sincerity, and hence, forgiveness—researchers are looking into how much more complex it gets when moved onto an online environment. Social network systems have expanded audiences and communities from local to worldwide, making every post and detail much more profound. This goes back to one’s sense of self and what we want presented online. Matley (2018) investigates this concept by observing the function of speech acts on the platform app Instagram and examines how the hashtag #sorrynotsorry functions as a non-apology marker. Apologies operate as speech acts that serve as justification and accountability for behavior online, all to make users’ social value return to the positive scale (Matley, 2018; Hu et al., 2019). This is especially interesting considering how individuals can choose to present their whole lives for the world to see or keep themselves hidden behind anonymous accounts. This allows for perpetuation of self-conflict between social approval and sharing offensive opinions. Hashtags on social media are used to search for content, but also provides the user with the control to manipulate the interpretation of a post’s content (Matley, 2018). The #sorrynotsorry hashtag (essentially the phrase “Sorry, not sorry”), as studied by Matley (2018), has two components: the “sorry” and the “not sorry”. The “sorry” element functions as a face-mitigation strategy, which attenuates the offenses made within the content of the post in order to reestablish a positive face. The “not sorry” attached along conflicts with the initial “sorry” by expressing disregard for the recipient’s emotions, which threatens positive face and diminishes social approval (Matley, 2018). Moreover, the ironic hashtags attached to posts can be detrimental to social status. To add onto this research, our present study aims to explore essentially how differing levels of sincerity and the presence of an apology, using hashtags on a social network system attached to an apology post, can affect the favorability of whether the transgressor can be 6 HOW SINCERITY AFFECTS FORGIVENESS forgiven. Participants were all given a scenario in which Charlie Webb, a user on the social media platform Twitter, apologizes for an incident at the mall. Participants were randomly assigned to different conditions where Charlie offers either a sincere apology, an insincere apology, or no apology. The participants were then asked to rate Charlie’s actions and how favorable they view the apology offered. In general, it was predicted that participants in the sincere apology condition viewed the apology (and apologizer) more favorably than participants in both the no apology and insincere apology conditions, though participants viewed an insincere apology less favorably than no apology. More specifically, if participants view a sincere apology (compared to an insincere apology or no apology), then they will more strongly agree that the apology showed an acknowledgement of wrongfulness and an acceptance of responsibility, though participants who viewed an insincere apology will more strongly disagree with these statements compared to those who saw no apology. In addition, if participants viewed a sincere apology (compared to an insincere apology or no apology), then they will more strongly agree that the apology is sincere, with participants ironically finding no apology more sincere than an insincere apology. 7 HOW SINCERITY AFFECTS FORGIVENESS References Hareli, S., & Eisikovits, Z. (2006). The role of communicating social emotions accompanying apologies in forgiveness. Motivation and Emotion, 30(3), 189-197. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1007/s11031-006-9025-x Hu, M., Cotton, G., Zhang, B., & Jia, N. (2019). The influence of apology on audiences’ reactions toward a media figure’s transgression. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000195 Leunissen, J., de Cremer, D., Reinders Folmer, C., & van Dijke, M. (2013). The apology mismatch: Asymmetries between victim's need for apologies and perpetrator's willingness to apologize. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 315324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.12.005 Matley, D. (2018). “Let's see how many of you mother fuckers unfollow me for this”: The pragmatic function of the hashtag #sorrynotsorry in non-apologetic Instagram posts. Journal of Pragmatics. 133. 66-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.06.003 Zechmeister, J. S., Garcia, S., Romero, C., & Vas, S. N. (2004). Don't apologize unless you mean it: A laboratory investigation of forgiveness and retaliation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(4), 532–564. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.4.532.40309