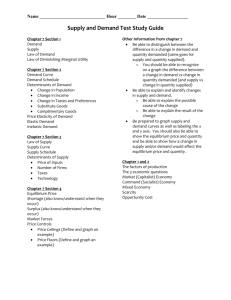

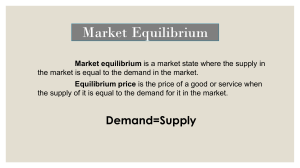

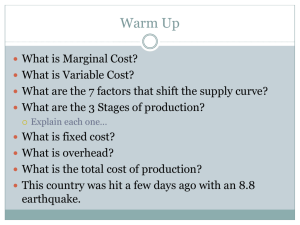

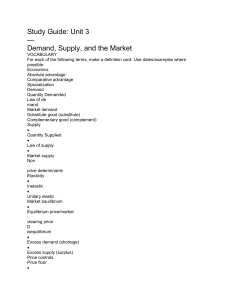

Module 3 Demand and Supply The third chapter of this module is designed to introduce you to the principles of microeconomics and familiarize you with supply and demand diagrams, the most basic tool economists employ to analyze shifts in the economy. After completing this unit, you will be able to understand shifts in supply and demand and their implications for price and quantity sold. You will also learn how to analyze how consumers respond to a shift in the price of the goods they consume. This understanding of the basic forces of supply and demand will serve as a foundation for the economic analysis you will undertake in the remainder of this course. Learning Outcomes By the end of this chapter, you will be able to: 1) Explain demand, quantity demanded, and the law of demand 2) Identify a demand curve and a supply curve 3) Explain supply, quantity supply, and the law of supply 4) Explain equilibrium, equilibrium price, and equilibrium quantity 5) Explain the determinants of demand 6) Explain the determinants of supply 7) Explain and graphically illustrate market equilibrium, surplus and shortage 8) Analyze the consequences of the government setting a binding price ceiling 9) Analyze the consequences of the government setting a binding price floor 3 3.1 DEMAND Relationship between Price and Quantity Demanded The demand for a good is the quantity of the good that consumers are willing and able to buy at each price over a period of time, ceteris paribus. The quantity demanded of a good refers to the quantity of the good that consumers are willing and able to buy. The law of demand states that there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. When the price of a good falls, the quantity demanded will rise. Conversely, when the price of a good rises, the quantity demanded will fall. The demand curve of a good shows the quantity demanded of the good at each price over a period of time, ceteris paribus. The demand curve is downward sloping due to the law of demand. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 49 Demand Curve The demand schedule shown by Table 1 and the demand curve shown by the graph in Figure 1 are two ways of describing the same relationship between price and quantity demanded. Figure 1. A Demand Curve for Gasoline. The demand schedule shows that as price rises, quantity demanded decreases, and vice versa. These points are then graphed, and the line connecting them is the demand curve (D). The downward slope of the demand curve again illustrates the law of demand—the inverse relationship between prices and quantity demanded. Price (per gallon) Quantity Demanded (millions of gallons) $1.00 800 $1.20 700 $1.40 600 $1.60 550 $1.80 500 $2.00 460 $2.20 420 Table 1. Price and Quantity Demanded of Gasoline Demand curves will appear somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, or they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that they slope down from left to right. So demand curves embody the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and conversely, as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 50 The law of demand can be explained with the concept of diminishing marginal utility. Utility refers to the satisfaction obtained by consumers from consuming a good. Marginal utility is the additional satisfaction resulting from consuming one more unit of a good. The more a consumer has of a good, the less they will value it at the margin and this is known as diminishing marginal utility. Due to diminishing marginal utility, consumers will only increase the consumption of a good if the price falls. The law of demand can also be explained with the concepts of substitution effect and income effect. When the price of a good falls, the real income of consumers will rise as they will be able to buy a larger amount of goods and services with the same amount of nominal income. This will induce them to buy more of the good. This effect is known as the income effect of a price fall. Furthermore, when the price of a good falls, the good will become relatively cheaper than other goods. This will induce consumers to substitute the good for other goods. This effect is known as the substitution effect of a price fall. Note: Ceteris paribus is Latin which means other things being equal. 3.2 Movements along versus Shifts in the Demand Curve A change in quantity demanded occurs when quantity demanded changes due to a change in price. This is shown by a movement along the demand curve. In the above diagram, the quantity demanded (Q) increases from Q 0 to Q1 due to a fall in the price (P) from P0 to P1. This is called an increase in quantity demanded. A change in demand occurs when quantity demanded changes due to a change in a non-price determinant of demand. In other words, quantity demanded changes at the same price. This is shown by a shift in the demand curve. In the above diagram, the quantity demanded (Q) increases from Q 0 to Q1 at the same price (P0) due to a change in a non-price determinant of demand. This is called an increase in demand. Note: Students should not mix up a change in quantity demanded which is shown by a movement along the demand curve and a change in demand which is shown by a shift in the demand curve as failure to do so will lead to a great loss of marks in the examination. 3.3 Non-price Determinants of Demand Tastes and Preferences A change in tastes and preferences towards a good will lead to an increase in the demand and vice versa. Tastes and preferences are affected by a number of factors such as technological advancements and campaigning. For example, the inventions of smartphones and tablets have led to a change in tastes and preferences from print publications to digital publications. Healthy living campaigns have led to a change in BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 51 tastes and preferences from non-diet soft drinks to diet soft drinks. These have increased the demand for digital publications and diet soft drinks and decreased the demand for print publications and non-diet soft drinks. Prices of Substitutes and Complements Substitutes are goods which are consumed in place of one another such as Coke and Pepsi. A rise in the prices of substitutes for a good will induce consumers to buy less of the substitutes resulting in an increase in the demand for the good and vice versa. For example, if the price of Pepsi rises, consumers will buy less Pepsi and more Coke. Complements are goods which are consumed in conjunction with one another such as car and petrol. A fall in the prices of complements for a good will induce consumers to buy more of the complements resulting in an increase in the demand for the good and vice versa. For example, if the prices of cars fall, consumers will buy more cars and more petrol. Substitutes and complements will be explained in greater detail in Chapter 4. Number of Substitutes and Complements An increase in the number of substitutes for a good will lead to a decrease in the demand for the good and vice versa. For example, if scientists found out that milk could be used as a substitute for shampoo, the demand for shampoo would decrease. An increase in the number of complements will lead to an increase in the demand for a good and vice versa. For example, if more models of digital cameras are introduced onto the market, the demand for memory cards will increase. Level of Income When consumers’ income rises, the demand for some goods will increase and these goods are called normal goods. A normal good is a good whose demand rises when consumers’ income rises. There are two types of normal goods: necessity and luxury. A necessity is a good whose demand rises by a smaller proportion when consumers’ income rises. Examples of necessities include agricultural products and stationery. A luxury is a good whose demand rises by a larger proportion when consumers’ income rises. Examples of luxuries include private cars and branded watches. When consumers’ income rises, the demand for some goods will decrease and these goods are called inferior goods. An inferior good is a good whose demand falls when consumers’ income rises. Inferior goods are typically relatively low in quality. Examples of inferior goods include public transport and Daiso Products. Expectations of Price Changes If consumers expect the price of a good to rise, they will bring forward the purchase to avoid paying a higher price in the future. If the good can be resold such as residential properties, consumers will also buy the good to sell it at a higher price later. When these happen, the demand for the good will increase. Conversely, if consumers expect the price BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 52 of a good to fall, they will put off the purchase to enjoy a lower price in the future which will lead to a decrease in the demand. Size of the Population An increase in the size of the population will lead to an increase in the demand for certain goods and services. With the exception of a few countries such as Japan, most countries have been experiencing an increase in the size of the population. 4 4.1 SUPPLY Relationship between Price and Quantity Supplied The supply of a good is the quantity of the good that firms are willing and able to sell at each price over a period of time, ceteris paribus. The quantity supplied of a good refers to the quantity of the good that firms are willing and able to sell. The law of supply states that there is a direct relationship between price and quantity supplied. When the price of a good falls, the quantity supplied will fall. Conversely, when the price of a good rises, the quantity supplied will rise. The supply curve of a good shows the quantity supplied of the good at each price over a period of time, ceteris paribus. The supply curve is upward sloping due to the law of supply. Supply Curve A supply curve is a graphic illustration of the relationship between price, shown on the vertical axis, and quantity, shown on the horizontal axis. The supply schedule and the supply curve are just two different ways of showing the same information. Notice that the horizontal and vertical axes on the graph for the supply curve are the same as for the demand curve. Figure 2. A Supply Curve for Gasoline. The supply schedule is the table that shows quantity supplied of gasoline at each price. As price rises, quantity supplied also BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 53 increases, and vice versa. The supply curve (S) is created by graphing the points from the supply schedule and then connecting them. The upward slope of the supply curve illustrates the law of supply—that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied, and vice versa. Price (per gallon) Quantity Supplied (millions of gallons) $1.00 500 $1.20 550 $1.40 600 $1.60 640 $1.80 680 $2.00 700 $2.20 720 Table 2. Price and Supply of Gasoline The shape of supply curves will vary somewhat according to the product: steeper, flatter, straighter, or curved. Nearly all supply curves, however, share a basic similarity: they slope up from left to right and illustrate the law of supply: as the price rises, say, from $1.00 per gallon to $2.20 per gallon, the quantity supplied increases from 500 gallons to 720 gallons. Conversely, as the price falls, the quantity supplied decreases. The law of supply can be explained with the concept of profit maximisation. A rise in the price of a good will increase the profitability of selling the good. Therefore, firms which are profit-oriented will sell more of the good. The law of supply can also be explained with the concept of diminishing marginal returns. Suppose that a firm employs two factor inputs: capital and labour. Although labour is a variable factor input, capital is a fixed factor input. As the quantity of capital is fixed in the short run, the firm can increase production only by employing more labour. However, as each additional unit of labour will have less capital to work with, it will add less to total output than the previous additional unit and this is known as diminishing marginal returns. Due to diminishing marginal returns, to produce each additional unit of output, more units of labour will be required which will lead to an increase in marginal cost. Marginal cost is the additional cost resulting from producing one more unit of output. Therefore, firms will increase the production of a good only if the price rises. 4.2 Movements along versus Shifts in the Supply Curve. A change in quantity supplied occurs when quantity supplied changes due to a change in price. This is shown by a movement along the supply curve. In the above diagram, the quantity supplied (Q) increases from Q 0 to Q1 due to a rise in the price (P) from P0 to P1. This is called an increase in quantity supplied. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 54 A change in supply occurs when quantity supplied changes due to a change in a non-price determinant of supply. In other words, quantity supplied changes at the same price. This is shown by a shift in the supply curve. In the above diagram, the quantity supplied (Q) increases from Q 0 to Q1 at the same price (P0) due to a change in a non-price determinant of supply. This is called an increase in supply. Note: Students should not mix up a change in quantity supplied which is shown by a movement along the supply curve and a change in supply which is shown by a shift in the supply curve as failure to do so will lead to a great loss of marks in the examination. 4.3 Non-price Determinants of Supply Cost of Production A rise in the cost of production will lead to a decrease in supply and vice versa. When the cost of production rises, firms will increase the price at each quantity to maintain profitability. In other words, they will reduce the quantity supplied at each price which will lead to a decrease in supply. The converse is also true. There are several factors that can lead to a change in the cost of production. For example, a fall in factor prices such as wages will lead to a fall in the cost of production and vice versa. Subsidy will decrease the cost of production and tax will have the opposite effect. Labour productivity refers to output per hour of labour. When labour productivity rises, which may be due to an increase in the skills and knowledge of labour or the efficiency of capital, firms will need a smaller amount of labour to produce any given amount of output. Therefore, the cost of production will fall. Production Capacity If the production capacity in the industry increases, which may occur due to an increase in the number of firms in the industry or an expansion of the production capacities of the existing firms, the supply of the good will increase. The converse is also true. Expectations of Price Changes If firms expect the price of a good to rise, they will hoard some of the output that they currently produce to sell it at a higher price in the future. This will lead to a fall in the supply of the good. The converse is also true. Profitability of Goods in Joint Supply Goods in joint supply refer to goods that are produced in the same production process. An example is petrol and diesel. In the process of refining crude oil to produce petrol, other grade fuels such as diesel are also produced. Therefore, if the demand for petrol BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 55 increases which will lead to an increase in the profitability, more petrol will be produced. When this happens, the supply of diesel will also increase. The converse is also true. Profitability of Substitutes in Supply Substitutes in supply refer to goods that are produced using the same factor inputs. An example is potatoes and tomatoes. If the demand for tomatoes increases which will lead to an increase in the profitability, some farmers who are currently producing potatoes will switch to the production of tomatoes which will lead to a decrease in the supply of potatoes. The converse is also true. Disasters (Natural and Man-made) Natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, and man-made disasters such as wars which may kill workers and destroy factories and machinery, may lead to a decrease in the supply of certain goods including agricultural products. Weather Conditions When weather conditions become less favourable, the supply of agricultural products will fall as harvests will decrease. The converse is also true. In the event of severe weather conditions, the supply of air travel will fall as airlines will be forced to cancel flights. 5 5.1 EQUILIBRIUM Equilibrium Price and Equilibrium Quantity Equilibrium—Where Demand and Supply Intersect Because the graphs for demand and supply curves both have price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis, the demand curve and supply curve for a particular good or service can appear on the same graph. Together, demand and supply determine the price and the quantity that will be bought and sold in a market. Figure 3.4 illustrates the interaction of demand and supply in the market for gasoline. The demand curve (D) is identical to Figure 3.2. The supply curve (S) is identical to Figure 3.3. Table 3.3 contains the same information in tabular form. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 56 Figure 3.4 Demand and Supply for Gasoline The demand curve (D) and the supply curve (S) intersect at the equilibrium point E, with a price of $1.40 and a quantity of 600. The equilibrium is the only price where quantity demanded is equal to quantity supplied. At a price above equilibrium like $1.80, quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded, so there is excess supply. At a price below equilibrium such as $1.20, quantity demanded exceeds quantity supplied, so there is excess demand. Price (per gallon) $1.00 $1.20 $1.40 $1.60 $1.80 $2.00 $2.20 Quantity demanded (millions of gallons) 800 700 600 550 500 460 420 Quantity supplied (millions of gallons) 500 550 600 640 680 700 720 Table 3.3 Price, Quantity Demanded, and Quantity Supplied Remember this: When two lines on a diagram cross, this intersection usually means something. The point where the supply curve (S) and the demand curve (D) cross, designated by point E in Figure 3.4, is called the equilibrium. The equilibrium price is the only price where the plans of consumers and the plans of producers agree—that is, where the amount of the product consumers want to buy (quantity demanded) is equal to the amount producers want to sell (quantity supplied). Economists call this common quantity the equilibrium quantity. At any other price, the quantity demanded does not equal the quantity supplied, so the market is not in equilibrium at that price. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 57 In Figure 3.4, the equilibrium price is $1.40 per gallon of gasoline and the equilibrium quantity is 600 million gallons. If you had only the demand and supply schedules, and not the graph, you could find the equilibrium by looking for the price level on the tables where the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied are equal. The word “equilibrium” means “balance.” If a market is at its equilibrium price and quantity, then it has no reason to move away from that point. However, if a market is not at equilibrium, then economic pressures arise to move the market toward the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity. Imagine, for example, that the price of a gallon of gasoline was above the equilibrium price—that is, instead of $1.40 per gallon, the price is $1.80 per gallon. The dashed horizontal line at the price of $1.80 in Figure 3.4 illustrates this above equilibrium price. At this higher price, the quantity demanded drops from 600 to 500. This decline in quantity reflects how consumers react to the higher price by finding ways to use less gasoline. Moreover, at this higher price of $1.80, the quantity of gasoline supplied rises from the 600 to 680, as the higher price makes it more profitable for gasoline producers to expand their output. Now, consider how quantity demanded and quantity supplied are related at this above-equilibrium price. Quantity demanded has fallen to 500 gallons, while quantity supplied has risen to 680 gallons. In fact, at any above-equilibrium price, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. We call this an excess supply or a surplus. With a surplus, gasoline accumulates at gas stations, in tanker trucks, in pipelines, and at oil refineries. This accumulation puts pressure on gasoline sellers. If a surplus remains unsold, those firms involved in making and selling gasoline are not receiving enough cash to pay their workers and to cover their expenses. In this situation, some producers and sellers will want to cut prices, because it is better to sell at a lower price than not to sell at all. Once some sellers start cutting prices, others will follow to avoid losing sales. These price reductions in turn will stimulate a higher quantity demanded. Therefore, if the price is above the equilibrium level, incentives built into the structure of demand and supply will create pressures for the price to fall toward the equilibrium. Now suppose that the price is below its equilibrium level at $1.20 per gallon, as the dashed horizontal line at this price in Figure 3.4 shows. At this lower price, the quantity demanded increases from 600 to 700 as drivers take longer trips, spend more minutes warming up the car in the driveway in wintertime, stop sharing rides to work, and buy larger cars that get fewer miles to the gallon. However, the below-equilibrium price reduces gasoline producers’ incentives to produce and sell gasoline, and the quantity supplied falls from 600 to 550. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 58 The market is at equilibrium (i.e., clear) at market price of P* = 4 and equilibrium quantity of Q* = Qd = Qs = 300 and there is no surpluses or shortages. —Whenever the market price is set above or below the equilibrium price, either a market surplus or a market shortage will emerge. —Surplus:oIf P > P* ⇒ Qs > Qd, surplus ⇒ producers ↓ P in attempt to ↓ excess inventory; Qs↓ and Qd↑. —Shortage:oIf P < P* ⇒ Qd > Qs, shortage ⇒ producers ↑ P and Qs↑ while Qd How to Calculate Equilibrium Price and Quantity BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 59 In the following paragraphs, we will look at how to calculate the equilibrium price and quantity mathematically. To do this, we follow a simple 5-step process: (1) calculate supply function, (2) calculate demand function, (3) set quantity supplied equal to quantity demanded and solve for equilibrium price, (4) plug equilibrium price into supply function, and (5) validate result by plugging equilibrium price into demand function (optional). Please note: For the sake of simplicity we use linear supply and demand functions in this article. However, although a bit more complicated, the same process can be applied to any other type of supply and demand functions. 1) Calculate Supply Function In its most basic form, a linear supply function looks as follows: QS = mP + b. In this equation, x and y represent the independent and dependent variables, m shows the slope of the function and b represents its y-intersect. We can use this basic form to calculate actual supply functions. All we need for this is two ordered pairs of price and quantity (e.g. at a price of a demand is b and at a price of c demand is d). With this information we can calculate the slope of the function (which is usually positive) and then solve for the y-intersect by plugging two of the initial values into the updated function. For a more detailed step-by-step guide on this, check out our article on how to calculate a linear supply function. Let’s look at an example to illustrate this. Think of an imaginary burger restaurant (Deli Burger). At a price of USD 3.00 per burger, Deli Burger is willing and able to sell 600 burgers. If the price of a burger increases to USD 4.00, it becomes more profitable to sell them, so the restaurant expands production and sells 800 burgers. With this information we can calculate the firm’s supply function as described above. Hence, Deli Burger’s supply function looks like this: QS = 200P + 0 (i.e. QS = 200P). 2) Calculate Demand Function Similar to the supply function, we can calculate the demand function with the help of a basic linear function QD = mP + b and two ordered pairs of price and quantity. As a matter of fact, the process of calculating a linear demand function is exactly the same as the process of calculating a linear supply function. However, unlike most supply functions the majority of demand functions has a negative slope. To understand why that is, make sure to read our step-by-step guide on how to calculate a linear demand function as well. With that being said, let’s revisit our example from above. So far we already know how many burgers Deli Burger is willing and able to sell at different prices. Now we need to find out how many burgers the customers are actually going to buy at those prices. Let’s assume they are willing and able to buy 1000 burgers at a price of USD 2.00. Meanwhile BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 60 if price increases to USD 4.00, they will only buy 800 burgers. With this information we can calculate the following market demand function: QD = -100P + 1200. 3) Set Quantity Supplied Equal to Quantity Demanded and Solve for Equilibrium Price Once we have calculated both the supply and the demand function, we can set quantity supplied (QS) equal to quantity demanded (QD). By definition, the intersection of the supply and demand curve represents the market equilibrium. At this point quantity supplied has to be equal to quantity demanded (i.e. QS = QD). Starting from this simple equation, we can replace both sides with their corresponding functions (see section 2 and 3). This allows us to solve the resulting equation for P and find the equilibrium price. So let’s apply this to our example. We know that according to the equilibrium condition QS = QD. Now we can simply replace QS with 200P (because QS = 200P) and QD with -100P + 1200 (because QD = -100P + 1200). This results in the following equation: 200P = -100P +1200. If we solve this equation for P we find that P = 4. Or in other words, the market reaches its equilibrium at a price of USD 4.00. 4) Plug Equilibrium Price into Supply Function Now that we know equilibrium price, we can finally calculate equilibrium quantity. To do this, we simply plug the equilibrium price we just calculated (see section 3) back into the supply function (see step 1). Next, we solve the resulting equation for QS to find the equilibrium quantity. Please note that it does not matter if we use the supply function or the demand function for this step. Both functions will return the same equilibrium quantity because – as we learned above – in the equilibrium QS is always equal to QD. In the case of our example that means we plug the equilibrium price (i.e. USD 4.00) into Deli Burger’s initial supply function QS = 200P. This results in the following equation QS = 200*4. Hence, the equilibrium quantity is 800 burgers. 5) Verify by Plugging Equilibrium Price into Demand Function (optional) Last but not least, we can verify our result by plugging the quantity and price we just calculated into the demand function. As mentioned above, the two functions should always return the same equilibrium quantity and price. This step is optional, but it’s a great way to validate your result during exams and quizzes and make sure your calculations are correct. Thus, to validate the result from our example, we can take the equilibrium quantity (800 burgers) and the equilibrium price (USD 4.00) and plug them back into the demand function QD = -100P + 1200. This leaves us with the following equation: 800 = -100*4 + 1200. Fortunately for us, the equation holds true. Therefore we can conclude that our calculations are correct. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 61 6 Price Controls Price floors and price ceilings are government mandated prices that attempt to control the price of a good or service. Price ceiling is usually imposed to keep down the price of something perceived as too expensive. To have any effect, it must be imposed below the market price. Example: Rent control on apartments. What effect do we predict? As with any below-equilibrium price in the example above, we expect to get a shortage. But in this case, buyers can’t raise the price by bidding against each other, because by law the price cannot rise. Using the short-side rule, we discover that rent control actually reduces the amount of housing made available to the public. Ironically, the price control may also raise the de facto price paid by consumers. From the demand curve, we can see that consumers would be willing to pay a very high price (much higher than the price ceiling or even the market price) for the reduced quantity (Qs) available. They are willing to pay this money if they can just find a way to do so – and they do, in the form of bribes, key fees, rental agency fees, etc. N.B.: If the price ceiling is imposed above the market price, it has no effect. A price floor is usually imposed to keep up the price of something perceived as too cheap. To have any effect, it must be set above the market price. Example: Agricultural price supports. These are imposed, usually, because farm lobbies have convinced the legislature that they are not earning enough to stay in business. What effect do we predict? As with any above-equilibrium price, we expect to get a surplus, this time persistent because sellers can’t bid down the price. And for many years, that’s exactly what the U.S. had. The government usually bought up the surplus (and dumped it on 3rd World markets). Note: If the price floor is imposed below the market price, it has no effect. Note: It’s easy to get confused if you’re not thinking clearly. An effective price ceiling is below the market price, while an effective price floor is above it. (Imagine a ceiling being too low and bumping your head, or a floor rising beneath your feet.) Analyzing Changes in Market Equilibrium Consider first a rightward shift in Demand. This could be caused by many things: an increase in income, higher price of substitute, lower price of complements, etc. Such a shift will tend to have two effects: raising equilibrium price, and raising equilibrium quantity. [↑P*, ↑Q*] Example: Consider the market for rental housing, and suppose that a new factory or industry opens up in the city, attracting more residents. Then there will be a rightward shift in demand, driving up both price and quantity. Note: The price of housing does go up, but not by as much as you might think, because the change in demand induces suppliers to bring more housing to market. This can be seen in the movement along the Supply curve. A leftward shift of demand would reverse the effects: a fall in both price and quantity. The general result is that Demand shifts cause price and quantity to move in the same direction. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 62 Now consider a rightward shift of supply (caused by lower factor price, better technology, or whatever). This will tend to have two effects: raising equilibrium quantity, and lowering equilibrium price. [↓P*, ↑Q*.] Example: A new immigration policy allows lots of low-wage labor to enter the steel business. The lower price of steel leads to a right shift in the supply of cars, so the price of cars falls and the quantity rises. A left shift of supply would reverse the effects, so the general result is that supply shifts tend to cause price and quantity to move in opposite directions. Now, what happens if both demand and supply both shift at once? In general, the two changes have reinforcing effects on either price or quantity, and offsetting effects on the other. Example 1: The computer industry. Incredible improvements in technology, as well as the entry of many new firms into the industry, have increased supply. Simultaneously, many people have become very aware of the benefits of computers, and new software has made computers more useful for a variety of projects, thereby increasing demand as well. The increase in demand tends to increase both P and Q. The increase in supply tends to lower P and raise Q. So both effects tend to raise quantity. But what happens to price? That depends on the relative size of the two changes. Observation of the computer industry shows that prices have actually fallen, so we can conclude that supply shifts have been relatively more important than demand shifts in this market. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 63 A similar pattern emerges in many high-tech products (CD players, DVD players). A possible complication: Much technological change has been in the form of higher quality, and consumers shift demand from lower quality to higher quality machines. This is not as easy to think about in the supply-and-demand framework. The price of a new, cutting edge computer has stayed about the same over time, at about $2000. Example 2: Higher education. (This example may not be totally accurate historically, but it demonstrates the point.) Supply has fallen because higher education is a labor-intensive business, and educated labor (which has to be attracted from other industries) has become much more expensive. Meanwhile, demand has increased because jobs for educated people have become increasingly attractive relative to other jobs. The increase in demand tends to increase both P and Q. The decrease in supply tends to raise P while lowering Q. So both forces tend to raise P, and that is confirmed by observation. But they work in opposite directions on Q. Our knowledge of the market for higher education tells us that Q has actually increased, meaning that the shift in demand has been relatively more important. When analyzing situations where both supply and demand shift at once, don’t let yourself be fooled by your graph. Your graph may appear to show clear changes in both price and quantity. But we know that one variable will experience an offsetting effect. Whether that variable appears to rise or fall depends entirely on how large you’ve drawn the curve shifts. (Take the computer example above. If you drew the demand shift bigger than the supply shift, you would mistakenly conclude that price should rise.) Unless you are provided with additional information about the size of the shifts, you can only make a prediction about one variable. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 64 Exercise No. 1 Demand and Supply Name: ____________________________ Course & Section: __________________ 1) Many changes are affecting the market for oil. Predict how each of the following events will affect the equilibrium price and quantity in the market for oil. In each case, state how the event will affect the supply and demand diagram. Create a sketch of the diagram if necessary. A) Cars are becoming more fuel efficient, and therefore get more miles to the gallon. B) The winter is exceptionally cold. C) A major discovery of new oil is made off the coast of Norway. D) The economies of some major oil-using nations, like Japan, slow down. E) A war in the Middle East disrupts oil-pumping schedules. F) Landlords install additional insulation in buildings. G) The price of solar energy falls dramatically. BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 65 H) Chemical companies invent a new, popular kind of plastic made from oil. 2) Consider the demand for hamburgers. If the price of a substitute good (for example, hot dogs) increases and the price of a complement good (for example, hamburger buns) increases, can you tell for sure what will happen to the demand for hamburgers? Why or why not? Illustrate your answer with a graph. 3) Suppose there is soda tax to curb obesity. What should a reduction in the soda tax do to the supply of sodas and to the equilibrium price and quantity? Can you show this graphically? Hint: assume that the soda tax is collected from the sellers BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 66 Exercise No. 2 Demand and Supply Name: ____________________________ Course & Section: __________________ Directions: Each of the questions or incomplete statements below is followed by five suggested answers or completions. Select the one that is best in each case and write the correct letter of your anwer in the space provided for. ___1) During a recession, economies experience increased unemployment and a reduced level of activity. How would a recession be likely to affect the market demand for new cars? A) Demand will shift to the right. B) Demand will shift to the left. C) Demand will not shift, but the quantity of cars sold per month will decrease. D) Demand will not shift, but the quantity of cars sold per month will increase. E) All of the above ___2. Unionized workers may be able to negotiate with management for higher wages during periods of economic prosperity. Suppose that workers at automobile assembly plants successfully negotiate a significant increase in their wage package. How would the new wage contract be likely to affect the market supply of new cars? A) Supply will shift to the right. B) Supply will shift to the left. C) Supply will not shift, but the quantity of cars produced per month will decrease. D) Supply will not shift, but the quantity of cars produced per month will increase. E) All of the above ___3. An increase in the demand for a good will cause A) an increase in equilibrium price and quantity. B) a decrease in equilibrium price and quantity. C) an increase in equilibrium price and a decrease in equilibrium quantity. D) a decrease in equilibrium price and an increase in equilibrium quantity. E) None of the above ___4. An increase in the supply of a good will cause A) an increase in equilibrium price and quantity. B) a decrease in equilibrium price and quantity. C) an increase in equilibrium price and a decrease in equilibrium quantity. D) a decrease in equilibrium price and an increase in equilibrium quantity. E) None of the above ___5. The law of demand states that the quantity of a good demanded varies A) inversely with its price. B) directly with population.C) directly with income. D) inversely with the price of substitute goods E) None of the above ___6. Which of the following is consistent with the law of demand? A) A decrease in the price of a gallon of milk causes a decrease in the quantity of milk demanded. B) An increase in the price of a soda causes a decrease in the quantity of soda demanded. C) An increase in the price of a tape causes an increase in the quantity of tapes demanded. D) A decrease in the price of juice causes no change in the quantity of juice demanded. E) None of the above BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 67 ___7. A drop in the price of a compact disc shifts the demand curve for prerecorded tapes leftward. Fromthat you know compact discs and prerecorded tapes are A) normal goods. B) substitutes.C) inferior goods.D) complements. E) luxury ___8. A substitute is a good A) of higher quality than another good. B) that is not used in place of another good. B) that can be used in place of another good. D) of lower quality than another good. E) None of the above ___9. People buy more of good 1 when the price of good 2 rises. These goods are A) normal goods.B) complements.C) substitutes.D) inferior goods. E) luxury ___10. Which of the following pairs of goods are most likely substitutes? A) compact discs and compact disc players B) lettuce and salad dressing B) cola and lemon lime soda D) peanut butter and gasoline E) None of tha above ___11. A complement is a good A) used in conjunction with another good. B) used instead of another good. C) of lower quality than another good. D) of higher quality than another good. E) None of the above ___12. Suppose people buy more of good 1 when the price of good 2 falls. These goods are A) substitutes.B) inferior.C) normal.D) complements. E. luxury ___13. A change in which of the following alters buying plans for cars but does NOT shift the demandcurve for cars? A) a 10 percent decrease in the price of car insurance B) a 20 percent increase in the price of a car C) a 5 percent increase in people's income D) an increased preference for walking rather than driving E) All of the above ___14. Which of the following would NOT shift the demand curve for turkey? A) a change in tastes for turkey B) B) a decrease in the price of ham C) an increase in income D) a change in the price of a turkey E) All of the above ___15. Which of the following does NOT shift the supply curve? A) an increase in the price of the good B) a fall in the price of a substitute in production C) a decrease in the wages of labor used in production of the good D) a technological advance E) All of the above BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 68 Exercise No. 3 Demand and Supply Name: ____________________________Course & Section: __________________ CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS 1. Illustration 1.1 Demand: For each of the fallowing cases, state how demand for the vehicle, “HONDA SIR”, behaves, i.e., whether there is an increase or decrease in demand or in quantity demanded. i) The price of gasoline rises because of a shortage in the world petroleum market. ii) A lower priced “TOYOTA REVO” enters the car market. iii) The country is hit by another recession, causing a fall in real incomes. iv) The government imposes a 10 per cent import levy on all imported car parts. v) A lower rate of fatalities in accidents involving Honda Sir is observed. 1.2 Supply: Indicate whether a movement upward or downward along the supply curve, or a shift leftward or rightward of the supply curve of MANGOES occurs for the following cases: i) The surge in export demand raises price. ii) The government imposes a price ceiling on mangoes to appease consumers who have not had enough of the fruit last year. iii) A new variety is developed which doubles the out per tree. iv) The current crop of mangoes is infested by fruit files. v) The price of pesticides against fruit files increases due to the 10 percent import levy. 1.3 Describe what will happen to equilibrium price and quantity of each of the commodities given the corresponding hypothetical situations. i) Coffee: The Philippine Medical Association announces that caffeine in coffee causes heart attack. ii) National Bookstore’s Books: book sale. Management engages in a one month cut-price iii) Rice: Government imports rice from Thailand. iv) Pork: Foot and mouth disease (FMD) hits thousands of pigs resulting in very high mortality rate. v) Cigarettes: Taxes on cigarettes are increased from P2.00 to P3.00 per pack. 1.4 Suppose the demand for gasoline is given by Qᴰ = 100 – 2P and the supply by Qˢ 20 + 6P i) What will be the equilibrium price and quantity for gasoline? BASIC MICROECONOMICS by: Exequiel Mendoza Perez 69