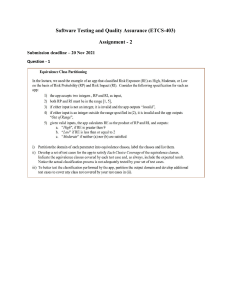

EFFECTS OF WORKPLACE RELATIONAL DYNAMICS ON FIRMS’ PRODUCTIVITY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Senior High School Department, Kidapawan Doctors College Incorporated, Kidapawan City In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the strand of ACCOUNTANCY, BUSINESS, AND MANAGEMENT ANGEL CHRIST C. QUIAMCO MISSY ROSE S. LEGARA OCTOBER 2019 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY As relationship been crucial in the social role, it is also critical in every business especially within the workers and employees inside the workplace. Every individual firm considered the dynamism of workplace particularly in interaction and relationship. The general features of workplace dynamics involve the relationships of the workplace, including organizational, team and personal relationships. The organizational form of workplace dynamics relates to operations on a quite different level. This is a planning and management policy level which defines a full spectrum of business operations. Workplace relational dynamics can include how people interact with each other and treat each other, the chain of command, employer expectations, and even the expected level of decorum within the workplace. It tends to differ from company to company and are often heavily influenced by the specific corporate or organizational culture. The relational theory of working (Blustein, 2011) provides a framework for understanding how working is embedded in external and internal relational contexts and how it can be viewed as an inherently relational act. Also, it has been suggested that relational schemas introduced as “coherent frameworks of relational knowledge that are used to derive relational implications of messages and are modified in accord with ongoing experience with relationships. They provide the cognitive equivalent of ‘definitions of relationships’ that guide message interpretation and production” (Planalp, 1985). According to Petryni (2019), relationships between employees and management are of substantial value in any workplace. Human relations is the process of training employees, addressing their needs, fostering a workplace culture and resolving conflicts between different employees or between employees and management. Understanding some of the ways that human relations can impact the costs, competitiveness and long-term economic sustainability of a business helps to underscore their importance. Job design and training are fundamental issues in workplace dynamics. The job design process is based on productivity, and it creates the team, personal and organizational relationships in the workplace. Training provides incentives and enhances productivity. This is an operational dynamic, providing the business with improved performance and functional benefits, while offering career opportunities and upgrade for staff. With the statement mentioned, the researchers want to find out if the workplace relational dynamics can affect one’s firm’s productivity and if there could be a significant increase or decrease of productivity in relation to relational dynamics. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES This study aims to identify the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firm’s productivity. Specifically, this study aims to answer the following: 1. Is there a significant decrease or increase of firm’s productivity in relation to workplace relational dynamics? HYPOTHESIS Ho: There is no significant effect of workplace relational dynamics on firm’s productivity. REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE Employee is a blood stream of any business. Investing in training and development programs is necessary for improving employee’s performance. The accomplishment or disaster of the firm depends on its employee performance. The effect of employee performance and on the basis of the review of the current evidence of such a relationship, offers suggestions for the top management in form of a checklist, appropriate for all businesses, to assess the employee performance and to find out the true cause(s) of the performance problem so the problem could be solved in time through desired training program. Workplace Dynamic Workplace Relational Dynamics There is a special case known as relational role (Barley, 1990; Nadel, 1957), defined as a set of characteristic behaviors that can only be performed in conjunction with a corresponding counter role and which designate patterns of interpersonal behavior by one status occupant toward the occupant of a specific other status (Nadel, 1957). For example, a business organization includes the parts of employee and manager. Both are statuses that involve different role behaviors. It is important to note that the manager cannot meaningfully enact a supervisor role without someone in the employee part enacting the complementary subordinate role, and vice versa. Further, by performing the behaviors associated with the subordinate role (e.g., obeying others), employees respond to and reinforce enactment of the supervisor role. In this sense, enactment of relational roles by a pair of status occupants tends to mutually cue and sanction their actions toward each other. Our core idea is that victimization of one person by another is a relational phenomenon involving their mutual role behaviors vice versa each other. It is not meaningful to talk about a bully aggressing in the absence of a victim to target. In addition, we argue that enactment of the roles associated with victims and perpetrators is likely to be mutually reinforcing by cueing responses that are perceived as legitimate and normal. We argue that within the context of enacting such relational roles, identifiable patterns of victimization are likely to rise. There are many social roles that people might enact in an organization. Because no theory can take into account all of these roles, we consider four specific roles that prior theory and research suggest may explain how parties in a dyadic relationship might victimize each other over time. In our discussion, we argue that there are two statuses, victim and perpetrator, each of which can be associated with different relational roles that people enact. Given that enactment of roles depend on the social situation and personal goals of the involved individuals (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1997; Baker & Faulkner, 1991), we identify different role archetypes that characterize various players, the relations between them, and the different forms of victimization that might emerge in these relations. We begin by considering the behavior of victims described in past studies that provides the empirical basis for our analytical classification of two of the archetypal social roles. The Reactive Perpetrator Role The organizational literature suggests that a second perpetrator type is one for whom aggressive or coercive actions are a response to some kind of norm violation or identity threat by another party (Anderson & Pearson, 199; Aquino & Douglas, 2003). Unlike the domineering perpetrator type described above, the type we refer to here as the reactive perpetrator exhibits retaliatory aggression that aims to harm the intended target for violating an established norm governing social interaction. In the absence of such provocation, the reactive perpetrator does not knowingly cause harm to others. Theoretical models of revenge (Bies, Tripp, & Kramer, 1997) and aggression as a form of social exchange (Glomb & Liao, 2003) support the notion that some perpetrators of harmful interpersonal behavior are motivated primarily by anger over interpersonal transgressions or the desire to reciprocate negative behavior. This perpetrator type is also implied in dynamic models of conflict escalation (e.g., Anderson & Pearson, 1999; Glomb, 2002), which suggest that minor violations of social norms can elicit a retaliatory response from the offended party that lays the groundwork for a repeating pattern of revenge and counter-revenge. This particular behavior pattern appears to relate to interpersonal processes that motivate one actor to become a perpetrator because he or she interprets another person’s behavior as a reasonable cue for enacting a retaliator role. As was the case for the provocative victim behavior pattern, the reactive perpetrator type illustrates the relational nature of victimization as role performance: Behavior is understood in terms of what occurs between individuals. Having described various roles associated with the victim and perpetrator statuses, we now consider how the interaction among people who enact of these roles can lead to different kinds of victimization. Access to Social Capital The context of role relations beyond dyadic power by examining how access to social capital might influence victimization patterns. Social capital is defined as the amount of goodwill and support available to an actor through the web of social relationships in which he or she is involved (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Social capital can be deployed to facilitate action by mobilizing social resources, such as influence, information, and solidarity (Burt, 1992; Podolny & Baron, 1997). Pertinent outcomes associated with a person’s access to social capital in organizations include career progression (Podonly & Baron, 1997), role innovation (Ibarra, 1993), and conflict reduction (Labianca, Brass, & Gray, 1998). Two sources of social capital may furnish social resources that provide protection from victimization, and these show how the web of social relationships takes different structural forms. Relational Justice and Organizational Productivity The concept of relational justice describes the relation between employees and their managers, who supposedly represent their respective organization. The consideration of employee viewpoints in matters concerning the employee’s welfare and organization’s growth is very essential. In relational justice, employees are expected to be treated equally without bias, from supervisors or the management. Moliner and colleagues developed the concept of relational justice and associated it to the group-or work-unit level and to employee burnout suggesting that perceived justice among employees can explain well-being beyond the individual level. Tyler and his colleagues opined that interpersonal treatment and procedures, viewed as fair, are prime indicators, for the individual, of respect from authorities and from their group, the contrary implying marginality and disrespect (Tyler et al, 1996). However, organizations that expect efficiency and high level of productivity from their employees should adopt relational justice interactive strategy. When an employee feels accepted and is appreciated by his supervisors for task well executed, he feels better motivated and confident to attain greater tasks. Cumulatively, when a good number of a company’s employee feels comfortable with their work environment and existing supervisor’s relational skills, it impacts on their work culture positively which could lead to improve organizational productivity. Firms’ productivity Productivity is a measure of the efficiency of a person, machine, factory, system in converting inputs into useful outputs. Productive workplaces are built on team work and shared vision. Workplace productivity is essential to employees, employers, and organization. Therefore, workplace productivity is pivotal for economic growth. Being productive is fundamental to business success as well as personal satisfaction. Organizational productivity is the amount of goods and services that a worker produces in a given amount of time. Workforce or organizational productivity is a measure for an organization or company, a process, an industry or a country (Goodman, 2003). Researchers have obtained measures of individual performance to include speed, accuracy, and time needed to learn, and have used these to estimate individual productivity at the workplace. The implicit and explicit assumption underlying these efforts has been that increased individual productivity will increase organizational productivity. (Locke an Latham 2005). However, at its most basic, productivity is the amount of value produced by the amount of cost (or times) required to do so. And while this equation seems simple enough on the surface, the strategies for optimizing it have evolved dramatically over the last two decades (Goodman, 2003; Locke and Latham, 2005). With the advent of technology massive personal productivity gains have been enabled. Computers, spreadsheets, email and other advances have made it possible for an average employee to seemingly produce more in the day than was previously possible in a year. arguably, it is important to affirm that if individuals are able to perform their work much better and faster, overall organizational productivity is inevitable. Team Building and Organizational Productivity Team work over the years has remained the ultimate competitive advantage adopted by most organizations. In today’s scenario, teams have come to be considered as a central element in the functioning of organizations. The use of teams has been facilitated by many studies reporting the positive relationship between team-based working and the quality of products and services offered by an organization (Neelam and Shilpi 2015) Organizations have realized that highly effective teams can positively affect the company and help them stay competitive. Therefore, businesses continue to search for ways to improve teamwork through training and development. Buller and Bell (2000) has remarked that “one of the most popular intervention techniques in organizational development is team building. Notably, most of the research literature indicates that the concept of team building becomes potentially, a powerful intervention for enhancing organizational performance through employee development when the circumstances of the specific team and organizational context are appropriate (Woodcok, 1989, Dyer, 1997, De Meuse and Liebowitz, 1981). Managers must recognize that they play a central role in effective team building. Team building involves a wide variety of activities presented to organizations and aimed at improving team performance. It is a philosophy of job design that sees employees as members of interdependent teams rather than individual workers (Fapohunda, 2013) Fajana (2002) asserts that team work is an integration of resources and inputs working in harmony to achieve organizational goals, where roles are prescribed for every organizational member, challenges are equally faced and incremental improvements are sought continually. More so, Dianna (2006) affirms that teamwork is a form of collective work that might involve individual tasks, but usually include some kind of collective task where each member is contributing part of a collective written document that is supposed to reflect the collective wisdom of the group. Remarkably, recent studies show that employee working within the team can produce more output as compared to individual (Jones, et al 2007). One research study concluded that the good manager is the one who assigns the responsibilities to his/her employee in a form of group or team in order to make maximum output from employees (Ingram, 2000). Another study concluded that it should be possible to design a system of team building within every organization for employees in order to promote and distribute best practice and maximize output or productivity. Conti and Kleiner (2003) opined that organizations with teams will attract and retain the best people. This in turn will create a high performance organization that is flexible, efficient, and most importantly, profitable. From the foregoing discussion, it seems that the relationship exists between teambuilding and organizational productivity. The researchers also agree with the views of the previous scholars and therefore conclude that team building influences organizational productivity. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK Relational Cognition Theory AccordiRelational cognition theory offers a theoretically rich lens for uncovering the complex cognitive processes involved with mentoring and other positive relationships at work. Relational cognition theory extends social cognition theory to relationships for the purpose of understanding the cognitive processes underlying social interactions (cf. Berscheid, 1994; Fiske, 2004; Haslam, 2004). Social cognition theory examines how people mentally organize and represent information about themselves and others (Fiske, 1992). The building block of social cognition theory is schemas (Markus & Zajonc, 1985). Schemas are mental knowledge structures that guide an individual’s behaviors in social interactions (Bersheid, 1994; Fiske & Taylor, 1984; Schneider, 1973). Schemas are developed through past experiences and affect our expectations about our own behavior, the behavior of others, and the nature and outcomes of our future social interactions (Markus & Zajonc, 1985). Schemas influence the kinds of social information that we attend to, the categorization and interpretation of new information, and the storage and retrieval of the information from our memory (Berscheid, 1994; Markus & Zajonc, 1985). In essence, schemas are organized structure of tacit knowledge that serve to construct, construe, and evaluate the behavior of self, others, and the relationship (Baldwin, 1992; Planalp, 1987). Relational Schemas. Relational Schemas. Planalp (1985, 1987) introduced relational schemas as “coherent frameworks of relational knowledge that are used to derive relational implications of messages and are modified in accord with ongoing experience with relationships. They provide the cognitive equivalent of ‘definitions of relationships’ that guide message interpretation and production” (Planalp, 1985, p. 9). Baldwin’s framework of relational schemas (Baldwin, 1992, 1997, 1999) integrates and extends Planalp’s ideas by drawing from symbolic interactionist theory (Cooley, 1902; Mead, 1934), social-cognitive models of personality (Schneider, 1973), relational models theory (Fiske, 1992), interpersonal theory (Safran, 1990), attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969), script theory (Tomkins, 1987), and relational-self theory (Horowitz, 1989; Ogilvie & Ashmore, 1991). Baldwin (1992) defined relational schemas as “cognitive structures representing regularities in patterns of interpersonal relatedness” (p. 461) with three interrelated components: a self-schema, an other-schema, and an interpersonal script that guides patterns of interactions in the relationship. Selfschemas denote mental representations about one’s self in a given relationship. This idea is grounded in the view that individuals have multiple selves and that a particular subset of the self, the working self-concept, is activated in a given relational context (Markus & Kunda, 1986). Ogilvie and Ashmore’s (1991) model of relational self-elaborates the process of internalizing relationships into the working model of the self: “We not only internalize and mentally represent ourselves and others; we also form images of what we are like and how we feel when we are with specific other people in our lives” (p. 286). They observed that self-schemas of “who I am when I’m with you” are influenced by past experiences and affect future behavior (Ogilvie, Fleming, & Pennell, 1998). Finally, they offered the provocative idea that individuals develop constellations of self with other structures that reflect more generalized patterns of experiences across similar types of relationships (Ogilvie & Ashmore, 1991). In essence, self-schemas encompass both cognitive structures envisioning “who I am when I’m with you” and, more generally, “who I am when I’m with someone like you.” Individuals therefore use both specific relationships and generic prototypes in their self-schemas. In addition to self and other schemas, relational schemas also include interpersonal scripts that guide roles and behaviors in the relationship (Baldwin, 1992). Drawing on script theory (Tomkins, 1987) and other models of interpersonal scripts (Abelson, 1981; Anderson, 1983; Schank & Abelson, 1977), Baldwin (1992) defined interpersonal scripts as “a cognitive structure representing a sequence of actions and events that defines a stereotyped relational pattern” (p. 468). Interpersonal scripts develop from past experiences and interactions (Tomkins, 1987) and reflect culturally shared systems of meaning (Stryker & Statham, 1985). CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The conceptual framework presents the schematic diagram about the relationship of the variables. The independent variable is the workplace relational dynamics of the business and the dependent variable is the firm’s productivity. INDEPENDENT VARIABLE WORKPLACE RELATIONAL DYNAMICS DEPENDENT VARIABLE FIRMS’ PRODUCTIVITY Figure 1. represents the conceptualized relationship between variables used in this study. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY This study would be beneficial to the following proponents as they will use the results of the study in supporting their claims on their research and issues in their firms’ community. Manager, the results of the study will help them decide on the possible matters concerning the firm’s productivity and also make them understand the different cultivation of their works. It can also help them to estimate better choices and elaborate options. Employees, the results of the study can be used as their assistance of controlling one’s self and knowing their limitations inside the organization or in their workplace. Future researchers, it can give them background or references as they conduct their own study. Also, it can widen up their research as they fill up the unseen lapses of their study. Hence, the researchers will study more about the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firm’s productivity. Through this study the manager, employees, and future researchers will be guided as they go through situations that are quantifiable enough that relates to workplace relational dynamics as it affects the firm’s productivity. OPERATIONAL DEFINITION OF TERMS The following terms are consistently used in the research which were operationally defined by the researchers to clearly understand the context of the study. Firm refers to the different random businesses in Kidapawan City. Relational Dynamics refers to the model of relationship used by businesses in Kidapawan City. Productivity refers to the growth gained by businesses in Kidapawan City. Workplace refers to the place and the area inside a business wherein working is visible. SCOPE AND LIMITATION OF THE STUDY This study is limited in finding the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firm’s productivity. The respondents of this study will be 60 employees from at least three identified big businesses in Kidapawan City. The data for the firm’s productivity will be gathered from the month of September 2019 only and will further focus on the employee’s response on the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firm’s productivity. Extraneous variables, such as the performances in the business are not explored in the study. CHAPTER II METHODOLOGY This chapter contains the research design, research locale, population and sample, research instrument, data collection, data analysis, statistical tools, and ethical considerations used during the experimentation. RESEARCH DESIGN Correlational research design was used in collecting data from the respondents since it uses quantitative data analysis. A correlational study was carefully designed to ensure that there was no bias in the collection of data. The design is preferred because it is concerned with determining the level of relation between two or more quantifiable variables. RESEARCH LOCALE This study was conducted at Kidapawan Doctors Hospital Inc., Madonna Medical Center, Inc., and Kidapawan Medical Specialist Center Inc. researchers took three days for their survey. The POPULATION AND SAMPLE The sample of the population of this study stood at 60 employees, 20 employees in each of the three known hospitals’ in Kidapawan City. The Kidapawan Doctors Hospital Inc., Madonna Medical Center, Inc., and Kidapawan Medical Specialist Center Inc. are known hospitals’ in Kidapawan City with its high standard operating system when it comes to rendering services. Where in the researchers will surely have a reliable and credible sources of their study about the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firms’ productivity. RESEARCH INSTRUMENT The researchers used survey questionnaire in collecting data from the respondents. The researchers designed an survey schedule as one of the data collection instrument for this study. The employees in the three hospitals were surveyed. The interview questions were aimed in eliciting relevant information concerning to the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firms’ productivity. A questionnaire designed by the researchers entitled “Effect of Workplace Relational Dynamics on Firms’ Productivity” was used in the study. The content of the instrument was based on the findings of the survey conducted. The questionnaire has sections: The instrument was structured in the modified Likert fashion, on a 4 – point scale, ranging from (4) “strongly agree”, through (3) agree, (2) “disagree” to (1) “strongly disagree”. Subjects were then instructed to respond to their degree of agreement with the statements contained in the instrument. The results were tagged as G+ numeric for good results and B+ numeric for bad results. DATA COLLECTION The data collection for this study was carried out through a survey questionnaire. The researchers first secured a letter of consent to where the study will be conducted. After which, the researchers proceeded to the actual survey in which the researchers provided and handed the questionnaires to the respondents for them to answer. Together with the research instrument, attached was the informed consent contained the purpose and the procedure of the study for the respondents. After the respondents answered the survey questionnaire, the researchers evaluated the results. Then, the researchers analyzed and finalized the gathered information of the respondents. DATA ANALYSIS After the data were collected, identified and encoded all the data information, researchers carefully scrutinize and analyze the information gathered. The researchers made a simple technique that help them easily identified the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firms’ productivity. They provided symbols that directly represent either the effects of workplace relational dynamics on firm’s productivity were good or not. The effects were tagged as G plus numeric for good and B plus numeric for bad. As soon as the researchers get the response of every employee they automatically proceeded to finalizing the data gathered. The researchers accurately followed the ethics in research and analyzed the data to ensure the validity and reliability of the results of this study. Strongly Agree Agree Disagree Strongly Disagree (4) (3) (2) (1) STATISTICAL TOOLS ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS Many ethical issues concerning confidentiality, authorization, credibility, and access to information protection will be dealt and pass with. Precisely, to assure the confidentiality of the employment contracts to be gathered and either the information is unveiling, an operation for the ethical approval will be politely and properly complied prior to the start of this correlational quantitative research study. The correlational quantitative research is bound within the Ethics of Research that shows the sensitivity and consideration of the study. The ethics of research include the following: honesty, objectivity, integrity, carefulness, respect for intellectual property, openness, confidentiality, legality and competence. The study is fair and truthful and the information gathered by the researchers should be factual and sincere to all scientific communications. Avoid bias in data analysis, data interpretation, peer review and other aspects that are expected to the goal of the study. The assurance of the promises and the agreements are being kept. The research information and the data gathered are carefully analyze and critically examined. The researchers should give proper and polite acknowledgement for all the contributions to research and never plagiarize. The protection of confidential communication and the personal information of the respondents. The researchers know and obey laws, and institutional policies. The maintenance and improvement of personal professional competence and expertise on lifelong education and learning. Things that being mention above are the most important thing to be considered in doing a research for the study.