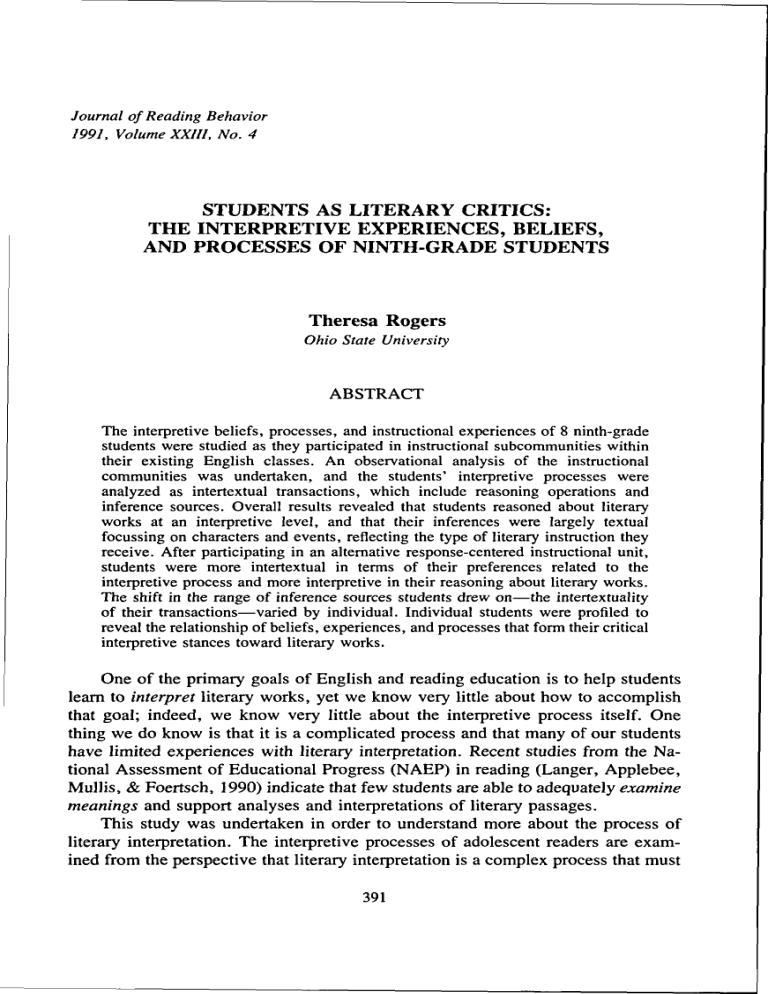

Students as Literary Critics: Interpretive Experiences & Beliefs

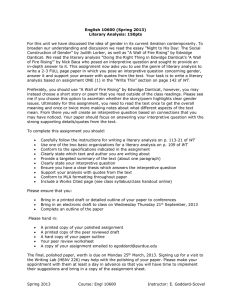

advertisement