CHAPTER 1 (Pages 4-27). Kisner Therapeutic Exercise Foundations and Techniques (7th ed.)

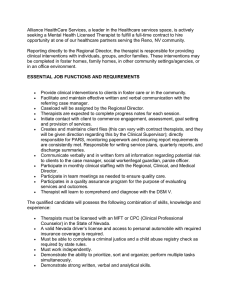

advertisement