7 Logline Mistakes & How to Fix Them for Screenwriters

advertisement

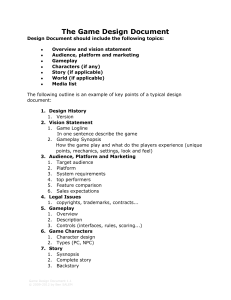

7 Crucial Logline Mistakes and How to Fix Them By: Timothy Cooper | March 6, 2015 by Timothy Cooper Click to tweet this article to your friends and followers! Why is a good logline important? After all, it’s not printed anywhere in your script. And it oversimplifies your story to the point of absurdity anyway, right? Wrong. A great logline is a vital step—arguably THE MOST IMPORTANT step—in writing your screenplay. If you don’t understand what your story is fundamentally about, and can’t distill it into a gripping, potential-packed one- or two-line summary, you’re not ready to move forward. It doesn’t matter weather you’re writing an introspective indie, a car chase–filled thriller, or an orc-laden fantasy epic: Your logline MUST demonstrate a powerful conflict with a twist that makes it stand out right away. Professional TV and film writers DO NOT START WRITING until they have a great logline. If they don’t yet know their story, they won’t devote months or years of their time to it. First, they have to hone their logline to decide whether it has the scope, audience appeal, and unique spin that makes it movie-worthy. Granted, the scriptwriting process can definitely be one path to discovering what your story is about—but the basic concept has to be there first. I made up all of the loglines below from scratch. However, their flaws are 100% based on totally real loglines I see every single day as a script consultant and screenwriting teacher. And these are just some of the missteps I see most often! You’ll learn about many more logline mistakes—and exactly how to fix them in order to create a sellable, irresistible premise—in my upcoming Writers Store webinar, Logline Master Class. Now, here are seven major logline problems that I frequently encounter. Does your logline suffer from one or more of these issues? Logline Mistake #1: It contains no irony. A Secret Service agent must risk everything to save the U.S. president he’s sworn to protect. It’s the Secret Service’s job to protect the president. Thus, anyone the Secret Service hires is probably quite good at his or her job. There is no hint of out-of-the-ordinary peril or major conflict here; this logline contains no surprising juxtaposition of any sort. In other words, there is no sense of, “This person is the least-suited to complete this task, so this movie will be a lot of fun.” Yoga teachers teach yoga; sharpshooters sharpshoot. To see those people doing those jobs isn’t extraordinary; that’s just life. But once the protagonist is out of his or her comfort zone, it creates major conflict. So a yoga teacher who is somehow put into the position of sharpshooting to protect the president—now THAT has potential. Logline Mistake #2: It brings nothing new to the table. When an all-powerful superhero falls in love with his arch-nemesis’s daughter, he must decide whether to reveal his true identity to her. This isn’t a bad logline by any means. Actually, it’s a pretty good first draft. But what makes this superhero different from the thousands of other superheroes we’ve seen in movies, comic books, and television? There’s nothing to makes me believe this character is particularly creative, new, or exciting. Also, if this protagonist’s number-one biggest issue is his love life…that’s not exactly a large enough conflict to be worth a producer/studio investment. It won’t deliver the fireworks people expect to see in a superhero movie. So what’s yourunique point of view on this character? How can YOU put someone who is all-powerful in a position of genuine, awesome peril? Logline Mistake #3: It ends with a mystery. A haughty corporate lawyer is forced to babysit his rebellious 6-year-old niece during New York City’s longest power outage. Will they get along—or annoy each other to death before the power returns? I certainly hope they WON’T get along, or else this will be a really boring movie. Assuming things don’t go well between them, that could lead to all sorts of hilarity and/or heartwarming drama. But as written, this is just a premise, not a specific, executable concept. Don’t leave us hanging with a question! It’s absolutely okay—even preferable—to give away the ending. Why? Because you still won’t be giving away the entire story, or the brilliance of your dialogue, or all of your the surprising twists along the way. Also, leaving the ending as a mystery makes me think you probably don’t actually know what happens—or have many interesting things to say after you get past that initial conflict. Show us how YOUR take on this dilemma can surprise or delight us in a way no one else could. Logline Mistake #4: It contains a dozen half-baked ideas rather than one solid, well-thought-out idea. When 12-year-old Kaitlyn’s wacky inventor uncle returns to town after decades in space, he reveals he’s discovered a portal to a new dimension…and Kaitlyn is the only one who can save humanity from the horrific flesh-eating aliens about to invade earth. Trust me when I say that I read loglines exactly like this all the time. My problem with this one (among others) is: It’s unclear whether this will be a YA film, a comedy, a sci-fi, a thriller, a horror, or all of the above. Sure, combining twodifferent genres (for example: horror and found footage, or sci-fi and thriller) is a great way to find a new take on a tired concept. But you can’t combine all of the genres in one, or your audience will get confused. It’s hard enough to flesh out a single idea into a coherent, original, and gripping story—don’t try to fit everything in there! If you can’t come up with a straightforward logline for your film, you might need to figure out what your story is actually about first. Logline Mistake #5: The genre has no official rules, but we’re supposed to somehow know your rules. After Sharon McGillicuddy is killed in an unfortunate forklift accident, the devil grants her just three days to prove that someone on earth loved her…or else she’ll be forced to return to hell for all time. One of the problems with stories involving ghosts, magic spells, witches, demons, angels, and so on is that we have no idea what the rules of those worlds are—they vary widely from story to story. For example, why does poor Ms. McGillicuddy go to hell—how is it decided who goes there? Why is the devil granting her three days to prove that someone loves her—is love something this devil cares about? Does he only make that concession for people who were unloved…and if so, why? Who came up with the arbitrary three-day deadline? More important: So what if Ms. McGillicuddy fails? After all, she’s already dead, so if she dies again, what’s the big deal? There is very little in this premise for me, a living person (as of this writing), to care about. There might be something here IF you can clarify why we should invest in this particular protagonist’s fate. But establishing a set of rules outside of the real world we live in—while certainly possible in many a fantasy, sci-fi, horror, etc.—isn’t easy. So you’ll have to work extra-hard on this one to make us care. Logline Mistake #6: A character must “discover” something about herself or “come to terms with” herself. Over the course of a long hike together, two siblings must come to terms with their best friend’s death. Or else…what? If the siblings don’t come to terms with their best friend’s death, they’ll finish the hike and go home. No big deal. Certainly not worth making an entire movie about it. Remember, EVERY script is about coming to terms with some part of yourself—but that’s just the internal conflict. The logline, however, should primarily describe what the film LOOKS like—that is, the external, visible conflict. Instead, what if the siblings disagree about which one of them caused the death? And what if it’s not just their best friend—it’s their dad? Their argument escalates during the hike, and eventually they’re so upset with each other that they each take a different route up a mountain. But then both get stranded on the mountainside during a blizzard. Now, if they can’t come to an agreement over their father’s death and refuse to help each other escape the wilderness…they’ll both be stranded out here and die. THAT is the beginning of a far superior logline, where the interior and exterior goals are inextricably intertwined. Logline Mistake #7: It only makes sense in movie land. Two successful gigolos must risk everything to do a strip show to pay for their ailing grandma’s heart surgery. I also encounter this sort of logline constantly—the type that only exists because it sounds funny (or cool, or scary, or exciting). But it violates so many real-world rules as to be unbelievable. In this case, if the gigolos are successful, why wouldn’t they have enough money to help out their grandma? Also, how is putting on a strip show that much of a risk if they’re gigolos already? Stripping shouldn’t be a big deal to them, unless they’ve been hiding their career from their grandma. And if that’s the case, why can’t they just find another way to pay for their grandma’s heart surgery, such as working at Target or driving a moving van? This sounds like the author is trying to write a combination of The Full Monty and Magic Mike. The difference is, those movies were filled with realistic characters who had real-world problems. This, on the other hand, is a conflict that is only a big deal in movie land—not in the real world. Make sure you’re not creating an illogical, pie-in-the-sky premise just for the sake of a few funny scenes! Register for Timothy’s Logline Master Class Even though your logline isn’t printed anywhere in your script, it will color every page of your script. It is your entire premise. Want more powerful tips, engaging examples, case studies, innovative solutions, and a FREE email tuneup of your own unique logline? Just take my upcoming course at the Writers Store, Logline Master Class. Give yourself a major advantage before you begin: Write an intriguing, logical, and genuine logline to create the foundation for a brilliant script.