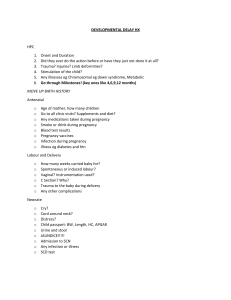

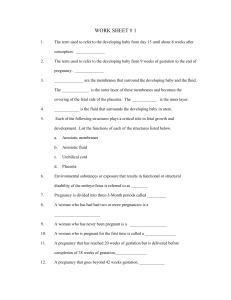

Prof. Dr. Yasamin Hamza Sharif Medical College • The obstetric examination is a type of abdominal examination performed in pregnancy. It is unique in the fact that the clinician is simultaneously trying to assess the health of two individuals – the mother and the fetus. • • Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language • Gain consent to proceed with the examination: • Position the patient on the clinical examination couch with the head of the bed at a 30-45° angle for the initial assessment. • Adequately expose the patient’s abdomen for the examination from the pubic symphysis to the xiphisternum (offer a blanket to allow exposure only when required). • Provide the patient with the opportunity to pass urine before the examination. • Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination. • General inspection • Clinical signs • Inspect the patient from the end of the bed whilst at rest, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology: • Inspect the patient’s face for relevant clinical signs: • Pain: if the patient appears uncomfortable • Melasma: benign dark and irregular hyperpigmented macules which are normal in pregnancy. • Pallor: a pale colour of the skin that can suggest underlying anaemia. It should be noted that healthy individuals may have a pale complexion that mimics pallor. • Jaundice: a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and whites of the eyes due to high bilirubin levels (e.g. obstetric cholestasis). • Oedema: a small amount of oedema is normal in the later stages of pregnancy however if there is widespread oedema affecting the arms, legs and face consider the possibility of pre-eclampsia. • Hands • The hands can provide lots of clinically relevant information and therefore a focused, structured assessment is essential. • Inspect the hands for relevant clinical signs: • Colour: pale hands suggest poor peripheral perfusion (e.g. hypovolaemic shock, aortocaval compression) and cyanosis may suggest underlying hypoxaemia. • Peripheral oedema: may be a normal finding in late pregnancy, but if widespread consider pre-eclampsia. If pre-eclampsia is suspected, you should check the patient’s blood pressure and perform urinalysis (looking for proteinuria). • Palmar erythema: a redness involving the heel of the palm that is a normal finding in pregnancy. • Temperature • Place the dorsal aspect of your hand onto the patient’s to assess temperature: • In healthy individuals, the hands should be symmetrically warm, suggesting adequate perfusion. • Cool hands may suggest poor peripheral perfusion (e.g. hypovolaemic shock, aortocaval compression). • Radial pulse • Palpate the patient’s radial pulse, located at the radial side of the wrist, with the tips of your index and middle fingers aligned longitudinally over the course of the artery. • Once you have located the radial pulse, assess the rate and rhythm. • Heart rate • Assessing heart rate: • You can calculate the heart rate in a number of ways, including measuring for 60 seconds, measuring for 30 seconds and multiplying by 2 or measuring for 15 seconds and multiplying by 4. • For irregular rhythms, you should measure the pulse for a full 60 seconds to improve accuracy. • Women typically have a higher baseline heart rate during pregnancy (80-90 beats per minute). • Blood pressure : • The aspect of BP measurement during pregnancy has received the most attention as to whether diastolic pressure should be registered by the 4th or 5th phase Korotkoff sound. Pregnancy is the only situation where phase 4 ever had much support as the best measure of diastolic pressure because it was stated that in many pregnant women, Korotkoff sounds might be audible even when there was no pressure in the cuff which would, of course, give a 5th‐phase diastolic reading of zero. • So , The diastolic blood pressure in pregnancy is denoted by the disappearance of the sound K5 , but should the sound not disappeared , the pressure at muffling of the sound K4 denotes the diastolic blood pressure. • Blood pressure should be taken on both arms at the first antenatal visit. It is recommended that the patient be seated, with feet supported, for 2–3 minutes before blood pressure is measured. Blood pressure should be taken on both arms at the first antenatal visit. The right arm should be used thereafter if there is no significant difference between the arms. When measuring blood pressure, SBP should be palpated at the brachial artery before inflating the cuff to 20 mmHg above the recorded level. • The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists( ACOG) advises that optimal measurement of blood pressure is performed with the patient comfortably seated , legs uncrossed, and her back and arm supported. The middle of the blood pressure cuff on the upper arm should be level with the heart . She should be relaxed and not talking. • measurement on the left arm in the left lateral recumbent position is a reasonable alternative to the seated position during labor . • Measurement on the RT arm while the patient in LT recumbent position may give false hypotension reading. • Blood pressure was measured with the woman comfortably seated, on the right arm, or semirecumbent (45 degree) posture , with the lower end of the cuff 2.5 cm above the antecubital fossa. The SBP was initially determined by palpation and then by auscultation using sphygmomanometer. The Korotkoff sounds were auscultated with the cuff deflated by approximately 2 mmHg per second. SBP was recorded as K1. The DBP was recorded as the disappearance K5 sound or K4( muffling sound) if no disappearance. • There are a number of different techniques for blood pressure assessment, including the auscultatory method, automated oscillometric devices, aneroid devices( using no liquid specifically operating by the effect of outside air pressure on a diaphragm forming one wall of an evacuated container) . • The auscultatory method with a mercury sphygmomanometer and the use of Korotkoff sounds was previously recommended as the gold standard technique. Mercury sphygmomanometers have been withdrawn owing to safety concerns (mercury toxicity)and replaced with aneroid devices, but these are particularly prone to calibration errors due to (mechanical trauma)and regular calibration is imperative to ensure accuracy . • Automated oscillometric devices are straightforward to use, but the physiological changes in healthy pregnancy and pathologic changes in preeclampsia may affect the accuracy of a device and monitors must be validated. • Abdominal inspection • Position the patient • The recommended positioning for a patient during pregnancy varies, depending on the current gestation: • Early pregnancy: position the patient supine on the couch, with the head end of the bed elevated to 15-30°. • Late pregnancy: position the patient in the left lateral position (tilted 15° to the horizontal level) to avoid compression of the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus (known as aortocaval compression). • Closely inspect the abdomen • Expose the abdomen appropriately, from the xiphisternum to the pubic symphysis and inspect for relevant clinical signs: • Abdominal shape: this may give an initial indication of the fetal lie. • Fetal movements: these are typically visible from 24 weeks gestation. • Surgical scars: may provide clues regarding previous abdominal surgery (e.g. caesarian section). • Linea nigra: a dark line running vertically down the middle of the abdomen (a normal finding in pregnancy). • Striae gravidarum: reddish or purple lesions that develop due to overstretching of the abdominal skin as the gravid uterus expands (commonly referred to as stretch marks). • Striae albicans: mature stretch marks which appear silver-like in colour and are less pronounced. • Abdominal palpation • Ask about abdominal tenderness before palpating the abdomen and continue to monitor the patient’s face for signs of discomfort throughout the examination. • Palpate the abdomen • Briefly perform light palpation over each of the nine regions of the abdomen to identify any tenderness or masses that may not relate to the pregnancy (e.g. appendicitis). • Palpate the uterus • Palpate the uterus to identify its borders, including the upper and lateral edges. • The uterine fundus can be found at different locations during pregnancy, depending on the patient’s current gestation: • 12 weeks gestation: pubic symphysis • 20 weeks gestation: umbilicus • 36 weeks gestation: the xiphoid process of the sternum • Symphyseal-fundal height • Symphyseal-fundal height is the distance between the fundus and the upper border of the pubic symphysis. After 20 weeks gestation, the symphyseal-fundal height should correlate with the gestational age of the fetus in weeks (+/- 2cm). • To measure the symphyseal-fundal height: • 1. Begin palpation of the abdomen just inferior to the xiphisternum using the ulnar border of your left hand. • 2. Locate the fundus of the uterus (a firm feeling edge at the upper border of the protrusion ). • 3. Once the fundus has been identified, locate the upper border of the pubic symphysis. • 4. Measure the distance between the upper uterine border and the pubic symphysis in centimetres using a tape measure. The distance measured should correlate with the gestational age in weeks (+/- 2cm). • To avoid bias, it’s best to place the tape measure facing down and only turn to view the numbers once in position. THANK YOU