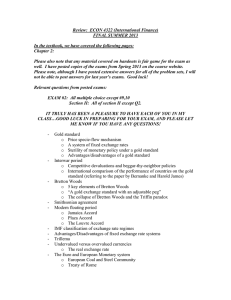

Final Review 45% 2hr 10 MQ 3 essay Chapter 11-22 Chapter 11Trade Policy in Developing Countries Import-Substituting Industrialization Import-substituting industrialization was a trade policy adopted by many low- and middle-income countries before the 1980s. The policy aimed to encourage domestic industries by limiting competing imports. The principal justification of this policy was/is the infant industry argument: Countries may have a potential comparative advantage in some industries, but these industries cannot initially compete with well-established industries in other countries. To allow these industries to establish themselves, governments should temporarily support them until they have grown strong enough to compete internationally. Import-substituting industrialization in Latin American countries worked to encourage manufacturing industries in the 1950s and 1960s. But economic development, not encouraging manufacturing, was the ultimate goal of the policy. Did import-substituting industrialization promote economic development? No, countries adopting these policies grew more slowly than others. It appeared that the infant industry argument was not as valid as some had initially believed. New industries did not become competitive despite or because of trade restrictions. Import-substitution industrialization involved costs and promoted wasteful use of resources: It involved complex, time-consuming regulations. It set high tariff rates for consumers, including firms that needed to buy imported inputs for their products. It promoted inefficiently small industries. Chapter 12 Controversies in Trade Policy One argument for an activist trade policy is that investment in high-technology industries produces externalities for the economy. But it is hard to identify which activities produce externalities and if so, to what degree they do. A second argument for an activist trade policy is that governments can give domestic firms a strategic advantage in industries with excess profits. But it is unclear if such a policy would succeed at giving a firm a strategic advantage or if it would be worthwhile. Some have opposed free trade because of the fact that workers in low- and middleincome countries earn lower wages and have worse working conditions than workers in high-income countries. But workers in low- and middle-income countries are predicted to have lower wages due to lower productivity, yet still have higher wages compared to their situation without trade. Some have proposed that trade negotiations should involve labor, environmental, or “cultural” standards, but these standards are generally opposed by governments of low- and middle- income countries. Chapter 13 National Income Accounting and the Balance of Payments The National Income Accounts Records the value of national income that results from production and expenditure. Producers earn income from buyers who spend money on goods and services. The amount of expenditure by buyers = The amount of income for sellers = The value of production. National income is often defined to be the income earned by a nation’s factors of production. 1. 2. 3. 4. 1) 2) Gross national product (GNP) is the value of all final goods and services produced by a nation’s factors of production in a given time period. What are factors of production? Factors that are used to produce goods and services: workers (labor services), physical capital (like buildings and equipment), natural resources and others. The value of final goods and services produced by US-owned factors of production are counted as US GNP. GNP is calculated by adding the value of expenditure on final goods and services produced: Consumption: expenditure by domestic consumers Investment: expenditure by firms on buildings & equipment Government purchases: expenditure by governments on goods and services Current account balance (exports minus imports): net expenditure by foreigners on domestic goods and services GNP is one measure of national income, but a more precise measure of national income is GNP adjusted for following: Depreciation of physical capital results in a loss of income to capital owners, so the amount of depreciation is subtracted from GNP. Unilateral transfers to and from other countries can change national income: payments of expatriate workers sent to their home countries, foreign aid and pension payments sent to expatriate retirees. Another approximate measure of national income is gross domestic product (GDP): – Gross domestic product measures the final value of all goods and services that are produced within a country in a given time period. – GDP = GNP − payments from foreign countries for factors of production + payments to foreign countries for factors of production Official international reserve assets are a component of the financial account, which records official assets held by central banks. The official settlements balance is the negative value of official international reserve assets, and it shows a central bank’s holdings of foreign assets relative to foreign central banks’ holdings of domestic assets. Official foreign exchange interventions are a way for the central bank to inject money into the economy or withdraw it from circulation. They can buy or sell international reserves in private asset markets in order to affect macroeconomic conditions without noticeably impacting the money supply. When a central bank purchases or sells a foreign asset, the transaction appears in its country's financial account as if a private citizen had carried out the same transaction The U.S. is the largest debtor nation, and its foreign debt continues to grow because its current account continues to be negative Chapter 14 Exchange Rates and the Foreign Exchange Market: An Asset Approach 1. Exchange rate notation The price of one nation’s currency in terms of another currency. ¥100/$: the price of 1 $ in terms of ¥ is ¥100 *Rules: Think of buying or selling the asset in the denominator 2. Currency appreciation/depreciation Calculation of % change (appreciation/depreciation) AUD/EUR % change = *Change in AUD/EUR ≠ change in EUR/AUD! * view the denominator as an asset (exchange rate is the price of the denominator) Appreciation/depreciation of the denominator Chapter 15 Money, Interest Rates, and Exchange Rates What Influences Aggregate Demand of Money? 1. Interest rates/expected rates of return: monetary assets pay little or no interest, so the interest rate on non-monetary assets like bonds, loans, and deposits is the opportunity cost of holding monetary assets. A higher interest rate means a higher opportunity cost of holding monetary assets lower demand of money. 2. Prices: the prices of goods and services bought in transactions will influence the willingness to hold money to conduct those transactions. A higher level of average prices means a greater need for liquidity to buy the same amount of goods and services higher demand of money. 3. Income: greater income implies more goods and services can be bought, so that more money is needed to conduct transactions. A higher real national income (GNP) means more goods and services are being produced and bought in transactions, increasing the need for liquidity higher demand of money. Chapter 16 Price Levels and the Exchange Rate in the Long Run The Fisher Effect The Fisher effect (named affect Irving Fisher) describes the relationship between nominal interest rates and inflation. Derive the Fisher effect from the interest parity condition: R$ R€ E e $/ € E$ / € E$ / € If financial markets expect (relative) PPP to hold, then expected exchange rate changes will equal expected inflation between countries: R$ R€ E e $/ € E$ / € E$ / € e US e EU R R e e € US EU Therefore, $ The Fisher effect: a rise in the domestic inflation rate causes an equal rise in the interest rate on deposits of domestic currency in the long run, when other factors remain constant. Chapter 17 Output and the Exchange Rate in the Short Run Real exchange rate *Formula for real exchange rate: et’: real exchange rate (USD/AUD) et: nominal exchange rate p: price level i: inflation Vs. relative PPP e: USD/AUD et: nominal exchange rate at time t e: nominal exchange rate at time 0 Chapter 18 Fixed Exchange Rates and Foreign Exchange Intervention 1. Changes in a central bank's balance sheet lead to changes in the domestic money supply. Buying domestic or foreign assets increases the domestic money supply. Selling domestic or foreign assets decreases the domestic money supply. 2. When markets expect exchange rates to be fixed, domestic and foreign assets have equal expected returns if they are treated as perfect substitutes. 3. Monetary policy is ineffective in influencing output or employment under fixed exchange rates. 4. Temporary fiscal policy is more effective in influencing output and employment under fixed exchange rates, compared to under flexible exchange rates. 5. A balance of payments crisis occurs when a central bank does not have enough official international reserves to maintain a fixed exchange rate. 6. Capital flight can occur if investors expect a devaluation, which may occur if they expect that a central bank can no longer maintain a fixed exchange rate: self-fulfilling crises can occur. 7. Domestic and foreign assets may not be perfect substitutes due to differences in default risk or due to exchange rate risk. 8. Under a reserve currency system, all central banks but the one that controls the supply of the reserve currency trade the reserve currency to maintain fixed exchange rates. 9. Under a gold standard, all central banks trade gold to maintain fixed exchange rates. Chapter 19 International Monetary Systems: An Historical Overview 1. Internal balance means that an economy enjoys normal output and employment and price stability. 2. External balance roughly means a stable level of official international reserves or a current account that is not too positive or too negative. 3. The gold standard had two mechanisms that helped to prevent external imbalances Price-specie-flow mechanism: the automatic adjustment of prices as gold flows into or out of a country. Rules of the game: buying or selling of domestic assets by central banks to influence flows of financial assets. 4. The Bretton Woods agreement in 1944 established fixed exchange rates, using the U.S. dollar as the reserve currency. 5. The IMF was also established to provide countries with financing for balance of payments deficits and to judge if changes in fixed rates were necessary. 6. Under the Bretton Woods system, fiscal policies were used to achieve internal and external balance, but they could not do both simultaneously, so external imbalances often resulted. 7. Internal and external imbalances of the U.S.—caused by rapid growth in government purchases and the money supply—and speculation about the value of the U.S. dollar in terms of gold and other currencies ultimately broke the Bretton Woods system. 8. High inflation from U.S. macroeconomic policies was transferred to other countries late in the Bretton Woods system. 9. Arguments for flexible exchange rates are that they allow monetary policy autonomy, can stabilize the economy as aggregate demand and output change, and can limit some forms of speculation. 10. Arguments against flexible exchange rates are that they allow expenditure switching policies, can make aggregate demand and output more volatile because of uncoordinated policies across countries, and make exchange rates more volatile. 11. Since 1973, countries have engaged in 2 major global efforts to influence exchange rates: 12. The Plaza Accords reduced the value of the dollar relative to other major currencies. 13. The Louvre Accords agreement was intended to stabilize exchange rates, but it was quickly abandoned. 14. Models of large countries account for the influence that domestic macroeconomic policies have in foreign countries. Chapter 20 Financial Globalization: Opportunity and Crisis International Regulatory Cooperation Basel accords (in 1988 and 2006) provide standard regulations and accounting for international financial institutions. Core principles of effective banking supervision was developed by the Basel Committee in 1997 for countries without adequate banking regulations and accounting standards. The financial crisis made obvious the inadequacies of the Basel II regulatory framework, so in 2010 the Basel Committee proposed a tougher set of capital standards and regulatory safeguards for international banks, Basel III. Chapter 21 Optimum Currency Areas and the Euro Theory of Optimum Currency Areas The theory of optimum currency areas argues that the optimal area for a system of fixed exchange rates, or a common currency, is one that is highly economically integrated. Fixed exchange rates have costs and benefits for countries deciding whether to adhere to them. Benefits of fixed exchange rates are that they avoid the uncertainty and international transaction costs that floating exchange rates involve. The gain that would occur if a country joined a fixed exchange rate system is called the monetary efficiency gain. The monetary efficiency gain of joining a fixed exchange rate system depends on the amount of economic integration. Joining fixed exchange rate system would be beneficial for a country if 1. trade is extensive between it and member countries, because transaction costs would be greatly reduced. 2. financial assets flow freely between it and member countries, because the uncertainty about rates of return would be greatly reduced. 3. people migrate freely between it and member countries, because the uncertainty about the purchasing power of wages would be greatly reduced. Chapter 22 Developing Countries: Growth, Crisis, and Reform 1. Some countries have grown rapidly since 1960, but others have stagnated and remained poor. 2. Many poor countries have extensive government control of the economy, unsustainable fiscal and monetary policies, lack of financial markets, weak enforcement of economic laws, a large amount of corruption, and low levels of education. 3. Many developing economies have traditionally borrowed from international capital markets, and some have suffered from periodic sovereign debt crises, balance of payments crises, and banking crises. 4. Sovereign debt, balance of payments, and banking crises can be self-fulfilling, and each crisis can lead to another within a country or in another country. 5. “Original sin” refers to the fact that poor and middle- income countries often cannot borrow in their domestic currencies. 6. Fixing exchange rates may lead to financial crises if the country is unwilling to restrict monetary and fiscal policies. 7. Weak enforcement of financial regulations causes a moral hazard and may lead to a banking crisis, especially with free movement of financial assets. 8. Geography and human capital may influence economic and political institutions, which in turn may affect long-term economic growth.