Grammar Vs. Usage

Grammar is a set of implicit rules that govern the formation of sentences. We may have no

explicit knowledge of these rules, but we obey them every time we speak and use them to

comprehend a sentence.

Usage is a set of explicit prescriptive rules that people impose on language to separate socially

acceptable grammatical sentences from others that are not socially acceptable.

Here are some interesting examples to illustrate the point:

1. After Sean got up, he had a shower.

2. Sean had a shower after he got up.

3. After he got up, Sean had a shower.

4. He had a shower after Sean got up.

In these sentences, “he” can only refer to Sean in the first three sentences. This is just a fact of

grammar. A speaker of English would not understand the word “he” in sentence 4 as relating

to Sean. The issue of usage would only come into the picture if people started to argue over

which of the first three sentences is the best form to use.

Another perspective offered by the author on the distinction is that bad grammar leads to

confusion, whereas bad usage leads to annoyance. The annoyance arises not because of lack of

understanding, but because a custom of usage has been breached.

Another set of sentences is offered, “which might be said to a little boy who has stolen a toy

from his sister”:

1. Give it to her!

2. Give it her!

3. Give her it!

4. It her give!

The first example (and in some countries the second) is standard usage, and the meaning is

clear. The third example is grammatical, in that the meaning is clear; but it is bad usage in the

view of many. The fourth example is ungrammatical, because it is virtually meaningless in

English—and thus it is also bad usage.

FINAL PREPOSITIONS

“This is something we cannot put up with.”

A sentence ending with a preposition is another situation where the distinction between

grammar and usage is clearly shown. The meaning of the sentence is clear—and thus,

according to the author’s definition, such usage is grammatical; but it may also be considered

bad usage—something “up with which we cannot put”, to quote Churchill.

Form, Function and Meaning

‘Form’ and ‘function’ are two extremely important concepts that you need to know about to

fully understand how grammar works.

‘Form’ refers to the category labels we use for the building blocks of grammar, i.e. word

classes, phrases, and clauses. Consider the following sentence:

·

My daughter bought a completely useless smartphone over the summer.

Scanning this sentence from left to right we can label each word as follows:

my: determiner

daughter: noun

bought: verb

a: determiner

completely: adverb

new: adjective

smartphone: noun

over: preposition

the: determiner

summer: noun

All the word class labels above are referred to as grammatical form labels. Still talking about

form, we can also say that:

my daughter is a noun phrase

a completely useless smartphone is also a noun phrase

over the summer is a preposition phrase

preposition phrase’, etc. are also grammatical form labels.

Digging deeper into the phrases a completely useless smartphone and over the summer we can

also say that:

completely useless is an adjective phrase within the larger noun phrase a completely

useless smartphone

with the preposition phrase over the summer, we have an embedded noun phrase,

namely the summer

(In some grammars we also have verb phrases such that bought on its own forms a verb phrase

or, if the direct object is included in the verb phrase, bought a new smartphone. The National

Curriculum doesn’t recognize verb phrases as such. Instead, verbs are regarded as the Heads

of clauses.

In summary, when we are talking about form, we are talking about structure. We can visualize

structure using what linguists call tree diagrams. For a completely useless smartphone, the tree

looks like this:

We are also talking about form when we have subordination in a phrase or clause. So, in the

following example the string that she lives in Leicester is a subordinate clause:

I know that she lives in Leicester.

‘Subordinate clause’ is a further example of a grammatical form label.

There’s more to say about form, but for now, this will do.

What about ‘function’? It is important to be aware that this label is ambiguous: it can have a

general sense and a grammatical sense. These are often confusing.

Let’s look at the general sense first. Consider the utterance below:

Fortunately, the pain went away very quickly.

The word fortunately in this sentence is an adverb that has a pragmatic function: it signals that

the speaker views what follows (namely the pain going away quickly) as a good thing.

Very in the adverb phrase very quickly is also an adverb that functions in a general sense to

‘intensify’ the meaning of the adverb quickly. So from a general functional point of view, we

can say that this word is an intensifier. This can be called a semantic function.

Turning now to the grammatical sense of ‘function’ (which is best referred to as ‘grammatical

function’), we need to say different things about the sentence above.

Taking the word fortunately again, this time we say that its grammatical function is Adverbial.

Words and phrases that have the grammatical function of Adverbial modify a particular unit in

a sentence. In this case fortunately modifies an entire clause. The example sentence very

quickly also has the grammatical function of Adverbial, but in this case, it modifies the

verb go. More specifically, it expresses how the pain went away. Adverbials can also express

other meanings, e.g. location and time, as in these examples:

We had a picnic in the park (preposition phrase functioning as Adverbial)

They left Hong Kong last week (noun phrase functioning as Adverbial)

Apart from Adverbial, other familiar grammatical function labels are Subject, Object,

and Complement (which includes Subject complement and Object complement).

The conclusion from all this is that we need to be careful when we use the word ‘function’

when talking about language and grammar. It’s important to make clear whether we are talking

about general functions, such as ‘disapproving’, ‘commenting’, ‘intensifying’, and the like, or

about grammatical functions, such as Subject, Object, and Adverbial.

Recall that ‘form’ refers to the category labels that we use for the building blocks of language,

i.e. word classes (e.g. noun, verb, adjective, etc.), phrases (e.g. noun phrase, adjective phrase,

etc.), and clauses (e.g. relative clause). By contrast ‘function’ refers to the grammatical

functions (e.g. Subject, Object, Adverbial, etc.) that the various building blocks can perform.

Consider the following sentences:

They closed the cinema last month.

The weather improved over the weekend.

He is an electrician.

The radio played a track that I love.

This class will visit a museum next week.

The paper has published the allegations.

The president hasn’t appeared on the news since the scandal erupted.

These are analyzed as follows using boxes to indicate the form (blue) and function (orange)

levels.

This is a simple sentence containing a Subject, Object, and Adverbial. Each of these takes the

form of a noun phrase. The verb in this example is transitive, which simply means that it takes

an Object. Notice that the verb carries the function label of Predicator.

In this case, we again have a Subject in the form of a noun phrase. The verb on this occasion

is intransitive, i.e. it does not take an Object. It is followed by a preposition phrase that

functions as an Adverbial.

In this sentence, the Subject takes the form of a pronoun. The verb is a special kind of verb

called a linking verb (also called copula). The noun phrase that follows it functions as Subject

Complement. The latter gives information about the Subject. (Incidentally, if you are

wondering why he is not a noun phrase, remember that in the National Curriculum, a word on

its own does not form a phrase. In some models of grammar, he would be both a pronoun and

a noun phrase.)

Here again, we have a sentence that contains a transitive verb (play). Both the Subject and

Object are in the form of a noun phrase. In this case, the noun phrase that functions as Object

has a relative clause inside it. Relative clauses give additional information about the noun they

go with, in this case, track.

In this example, the Subject and Object are again in the form of a noun phrase. We also have

an Adverbial in the form of a noun phrase. This sentence shows very clearly why we should

keep the levels of form and function apart: a noun phrase can perform different kinds of

functions. What about the verb? Well, in this case, we have two of them: visit is the main verb,

preceded by the modal auxiliary verb will. The latter indicates that ‘visiting a museum’ is an

event foreseen in the future.

In this example, apart from a Subject and Object in the shape of a noun phrase, we again have

two verbs, namely; the auxiliary verb have and the past participle form of the main

verb publish. Together these two verbs form the perfect form of the verb have.

In this last example, the verb is intransitive. It is followed by two units functioning as

Adverbial: one is a preposition phrase; the other is a subordinate clause introduced by

the subordinating conjunction since. Within the subordinate clause, the scandal functions as a

Subject. Because erupt is an intransitive verb, there is no Object in this clause.

Clause and Clause Complexes (Complexing)

Clause complexing comes under the logical metafunction of language, which in turn belongs

to the broader ideational metafunction of language. It refers to the relationships that exist

between clauses in a sentence. These relationships are of two types, taxis and logicosemantics.

Before we proceed further, here's a little intrusion on the analytical convention to be used

for clause complexes. Please note that clause complexes are indicated differently from

ranking clauses. Ranking clauses, as you know, are marked off by //...//. A clause complex,

on the other hand, is marked off this way: |||...|||.

Also, please note that if a clause complex contains one and only one ranking clause, it is

called a simplex.

Why do we need clause complexing? Here are two good reasons:

Reason 1: Clauses are interrelated in specific ways, and the mere division of a sentence into

its constituent clauses may obscure these relationships. Consider, for instance, the

following:

1. He signed the papers after the lawyer had read them and verified the facts.

There are altogether three ranking clauses in (1). Hence:

1. ||| He signed the papers // after the lawyer had read them // and verified the facts.

|||

You'll agree that the clausal division above obscures the fact that the second and third

clauses—"after the lawyer had read them and verified the facts"—are closely related (both

of them are dependent clauses and are subordinate to the main clause). We therefore need

some way to signal this relationship. And that's the general idea behind clause complexing.

Reason 2: Patterns of distribution in a text may be stylistically significant. A text that

contains many clause simplexes, for example, would have a very different effect on the

reader vis-à-vis a text with many clause complexes.

We'll now take a look at the two types of inter-clausal relationships in a clause complex,

beginning with the system of taxis and, if we're still conscious, logico-semantics.

Interdependency

Also known as taxis or the tactic system. The tactic system tells us whether the clauses are

of equal or unequal status:

Parataxis

-- relation between two elements of equal status. Arabic numerals are used

to signal parataxis. Since clauses in paratactic relation are equal in status, the clauses

are numbered sequentially, that is, "1" is used for the first clause, followed by "2" for

the second clause, and so on.

2. He saw the lecturer and groaned.

In (2), we have two clauses. Since both are main clauses, they are equal in status and are

therefore in paratactic relation. Hence:

2. ||| 1 He saw the lecturer // 2 and groaned. |||

Now consider the first two clauses in (3) below:

3. ||| When Rowan came near // and looked, // he was amazed at Alvin's ribcage. |||

Both these clauses are dependent clauses, and are therefore of equal status. For this reason,

they are also in paratactic relation. Hence:

3. ||| 1 When Rowan came near // 2 and looked, // he was amazed at Alvin's ribcage.

|||

Hypotaxis

-- relation between two elements of unequal status. Greek letters are used to

signal hypotaxis. The symbol α is always reserved for the main or dominant clause.

All other symbols, from β onwards are used for clauses dependent on the

main/dominant clause. Here's a simple example:

4. ||| β If you can't convince them, // α confuse them. |||

But ... arghhh ... I'm not familiar with the Greek alphabet!!!

Relax ... I've prepared a reference list for you. Turn to the right margin of this page to have

a look-see at the scientific- (scientistic?) looking letters. You don't need to memorise the

entire table, mind you. You just need to be familiar with the first three or four letters. (No

clause complex analysis will ever require you to use the full 24 letters of the Greek

alphabet!)

Now, let's return to the business of the day. In reality, as you might have guessed, a mixture

of parataxis and hypotaxis is far more common. This is exemplified in our earlier example

(3):

3. ||| β1 When Rowan came near // β2 and looked // α he was amazed at Alvin's

ribcage. |||

Here's a run-down of the steps taken in the analysis of (3):

Always use a top-down approach in your analysis. The sentence in (3) can be segmented

into two parts—the first being "When Rowan came near and looked", and the second,

"he was amazed at Alvin's ribcage". Since the first segment is subordinate to the

second, the two segments are hypotactically related.

We therefore use the symbol β for the first segment, and the symbol α for the second.

Since there are two clauses in the first segment, the symbol β is repeated for both

clauses. (There is only one clause in the second segment, so, thankfully, we do not

need to do the same for α.)

Now, within the first segment, we still need to account for how the two clauses are

related to each other. Since both of them are dependent clauses, they are in paratactic

relation. We therefore use "1" and "2" to signal this relation.

All this confusing mumbo-jumbo eventually gives us the analysis

you see above. It can

also be rewritten as follows: β1^β2^α where the caret symbol (^) simply indicates

sequence.

On a note of caution, please do not get the wrong idea that a clustering of dependent clauses

must mean that they are in paratactic relation. You must first make sure that no clause is

dominant over another before concluding so. Have a look at the following:

5. ||| If you can't confuse them // after failing to convince them, // clobber them. |||

Using the top-down approach, it is easy enough to see that the first two clauses are

dependent on the main clause "clobber them". However, if you look carefully at the

dependent clauses, you'll realise that they are not in paratactic relation. Specifically, "if you

can't confuse them" is the dominant clause, and "after failing to convince them" is dependent

on it. Hence:

5. ||| βα If you can't confuse them // ββ after failing to convince them, // α clobber

them. |||

Logico-semantics

And now for logico-semantics. This basically refers to the nature of the relation between

clauses. This relation is both logical and semantic, which explains why we have this

irritating term. The logico-semantic relationships are of two broad kinds—Expansion

(comprising Extension, Enhancement, and Elaboration), and Projection (comprising

Locution and Idea).

Expansion

Extension

-- where the extending clause adds something new, provides an exception,

or offers an alternative. The symbol "+" is used to signal Extension, as shown below

for both paratactic and hypotactic constructions:

6. ||| 1 Boney-I-Am sang poorly, // +2 and was booed off the stage. |||

7. ||| α Boney-I-Am sang poorly, // +β being booed all the way. |||

Enhancement

-- the enhancing clause provides circumstantial features of time, place,

cause/reason, condition, result, etc. The symbol "x" is used to signal Enhancement:

8. ||| 1 Alvin wanted a band, // x2 so he formed Boney-I-Am. |||

9. ||| α Alvin formed Boney-I-Am, // xβ because he wanted a band. |||

Elaboration

-- the elaborating clause restates, comments, exemplifies, or specifies in

greater detail. In the case of hypotaxis, elaboration is typically realised by nonrestrictive relative clauses. The symbol "=" is used to signal Elaboration:

10. ||| 1 The group Boney-I-Am recorded their first song 'Got Kut' in January 2002;

// =2 it sold 13 copies world-wide. |||

11. ||| α The group Boney-I-Am recorded their first song 'Got Kut' in January 2002,

// =β which sold 13 copies world-wide. |||

Projection

Locution

-- quoted or reported speech. The symbol (") is used to signal Locution. The

quoted or reported speech must be projected from a verbal process [please also note

from the examples below that the (") symbol goes with the projected clause, not the

projecting clause]:

12. ||| "1 "Let's record 'Got Kut'!"// 2 Alvin declared. |||

13. ||| α Alvin declared // "β that we should record 'Got Kut'. |||

Idea

-- quoted or reported thought. The symbol (') is used to signal Idea. The quoted or

reported thought must be projected from a mental process [again, note that (') is used

only for the projected clause, not the projecting clause]:

14. ||| '1 "When will we win the coveted Plastic Lizard Award?" // 2 Alvin wondered.

|||

15. ||| α Alvin wondered // 'β when they would win the coveted Plastic Lizard Award.

|||

Classification at the Sentence level

Every sentence is unique. That’s a declarative sentence.

But what makes every sentence unique? That’s an interrogative sentence.

When you understand each unique type of sentence, you’ll become a stronger writer. That’s a

conditional sentence.

Understanding the different sentence types and how they function together in your writing is

more than just recognizing them. Read on to learn more about how the different sentence types

operate, how to structure them, and how to make sure you’re using them correctly.

Types of Sentences based on function

Sentences can be classified in two ways: based on their function and based on their structure.

When you describe a sentence based on its function, you’re describing it based on what it does.

Declarative sentences

A declarative sentence is a sentence that:

Makes a statement

Provides an explanation

Conveys one or more facts

Declarative sentences are among the most common sentences in the English language. You use

them every day. They end with periods.

Here are a few examples of declarative sentences:

I forgot to wear a hat today.

Your pizza is doughy because you didn’t cook it long enough.

Spiders and crabs are both members of the arthropod family.

Interrogative sentences

An interrogative sentence is a sentence that asks a question, like:

How many pet iguanas do you have?

May I sit here?

Aren’t there enough umbrellas to go around?

One hallmark of interrogative sentences is that they usually begin with pronouns or auxiliary

verbs. When this kind of sentence does start with the subject, it’s usually in colloquial speech.

For example:

He went there again?

Rats can’t swim, right?

Exclamatory sentences

Much like an interrogative question ends with a question mark, an exclamatory sentence ends

with an exclamation mark. These sentences communicate heightened emotion and are often

used as greetings, warnings, or rallying cries. Examples include:

Hey!

High voltage! Do not touch!

This is Sparta!

The only difference between a declarative sentence and an exclamatory one is the punctuation

at the end. But that punctuation makes a big difference in how the reader or listener interprets

the sentence. Consider the difference between these:

It’s snowing.

It’s snowing!

Imperative sentences

An imperative sentence is a sentence that gives the reader advice, instructions, a command or

makes a request.

An imperative sentence can end in either a period or an exclamation point, depending on the

urgency of the sentiment being expressed. Imperative sentences include:

Get off my lawn!

After the timer dings, take the cookies out of the oven.

Always pack an extra pair of socks.

With an imperative sentence, the subject is generally omitted because the reader understands

they’re the one being addressed.

Conditional sentences

Conditional sentences are sentences that discuss factors and their consequences in an if-then

structure. Their structure is:

Conditional clause (typically known as the if-clause) + consequence of that clause.

A basic example of a conditional sentence is:

When you eat ice cream too fast, you get brain freeze.

Getting more specific, that sentence is an example of a zero conditional sentence. There are

actually four types of conditional sentences, which we cover in detail (and explain which tense

to use with each) in our post on conditional sentences.

Types of Sentences based on structure

The other way to categorize sentences is to classify them based on their structure. Each of the

types of sentences discussed above also fits into the categories discussed below.

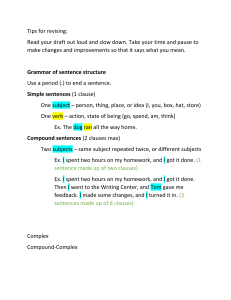

Simple sentences

A simple sentence is the most basic type of sentence. This kind of sentence consists of just one

independent clause, which means it communicates a complete thought and contains a subject

and a verb.

A few examples of simple sentences include:

How are you?

She built a garden.

We found some sea glass.

A simple sentence is the smallest possible grammatically correct sentence. Anything less is

known as a sentence fragment.

Complex sentences

In contrast to a simple sentence, a complex sentence contains one independent clause and at

least one dependent clause. While an independent clause can be its own sentence, a dependent

clause can’t. Dependent clauses rely on the independent clauses in their sentences to provide

context.

Dependent clauses appear after a conjunction or marker word or before a comma. Marker

words are words like whenever, although, since, while, and before. These words illustrate

relationships between clauses.

The following are complex sentences:

Before you enter my house, take off your shoes.

Matt plays six different instruments, yet never performs in public.

Compound sentences

Compound sentences are sentences that contain two or more independent clauses. In a

compound sentence, the clauses are generally separated by either a comma paired with

a coordinating conjunction or a semicolon. In some cases, they can be separated by a colon.

Examples of compound sentences include:

I was thirsty, so I drank water.

She searched through her entire closet; she could not find her denim jacket.

How can you tell if you have a compound sentence? Swap out your semicolon, colon, or

coordinating conjunction for a period. If you now have two distinct, complete sentences,

you’ve got a compound sentence.

Compound-complex sentences

When a sentence has two or more independent clauses and at least one dependent clause, that

sentence is a compound-complex sentence. These are long sentences that communicate a

significant amount of information. The clauses don’t need to be in any specific order; as long

as you’ve got at least two independent clauses and at least one dependent clause, you’ve got a

compound-complex sentence.

Here are a few examples of compound-complex sentences:

I needed a new computer, so I got a laptop because they’re portable.

The students were excited; they could go home early because of the power outage.

Mood and its Function

The mood in English grammar does not refer to the emotion of the action or anything like that.

Instead, the mood of the verbs refers to whether or not something is a fact. The intention of the

speaker/writer is understood by the mood of the verbs.

In English, there are mainly three kinds of mood:

Indicative mood

Imperative mood

Subjunctive mood

Each of the types has a particular function.

Indicative Mood

Indicative mood tells the reader/listener something factual. This mood is generally used in

making a statement or asking for a statement by a question. The statement can be factual

or presumed to be factual.

Example:

o Michel was the greatest musician.

o Where are you going?

o I am going to Texas.

Imperative Mood

Imperative mood makes a verb into a command or request. It always uses the second

person as the subject of the sentence and most of the time the subject remains hidden.

Example:

o Bring the bottle over here.

o Make me a cup of tea, please.

o Let her take her own decisions. (Here, ‘let’ is the verb of this sentence,

not ‘take’.)

Subjunctive Mood

Subjunctive mood indicates the possibility, wishes, or hypothetical statements. It is almost the

opposite of the indicative mood. This mood usually mixes the tense of the verbs and does not

follow the common usage of the tense.

Subjunctive has some different structures from the other structures of sentences.

Conditionals generally use the subjunctive mood.

Example:

o If you change this dress, I will take you with me.

o If I were in your shoes, I would not do it.

o If they were in America, they could not escape from it.

o If they had taken the vaccine, they would not have been affected.

Some certain verbs + the conjunction that requires the next clause to use the subjunctive mood

and the clause uses the base form of the verb in it.

The verbs are:

Advise – demand – prefer – require – ask – insist Propose – stipulate – command –

recommend Suggest – decree – order – request – urge – move

Structure:

Subject + the verbs of the above box (any tense) + THAT + subject + base verb + . . . . .

Example:

o

o

o

o

He insisted that I stay at home.

The office requires that we complete our work timely.

She commanded that he stop smoking.

I recommend that you wake up early.

Note: There are some clauses also which require the verb of the next clause to be in base form.

The clauses are:

It is/was + past participle form of the verb of the above box + THAT

It is/was urgent + THAT

It is/was necessary + THAT

It is/was important + THAT

Example:

o

o

o

It is important that you invite the prime minister in our wedding.

It was necessary that I make a fence.

It was recommended that you meet the principal.

In linguistics, grammatical

mood is

a grammatical feature

of verbs,

used

for

signaling modality.[1][2]: p.181, [3] That is, it is the use of verbal inflections that allow speakers to

express their attitude toward what they are saying (for example, a statement of fact, of desire,

of command, etc.). The term is also used more broadly to describe the syntactic expression of

modality – that is, the use of verb phrases that do not involve inflection of the verb itself.

Mood is distinct from grammatical tense or grammatical aspect, although the same word

patterns are used for expressing more than one of these meanings at the same time in many

languages, including English and most other modern Indo-European languages.

Finite and Predicators

Finite Verbs

In English grammar, a finite verb is a form of a verb that (a) shows agreement with

a subject and (b) is marked for tense. Nonfinite verbs are not marked for tense and do not show

agreement with a subject.

If there is just one verb in a sentence, that verb is finite. (Put another way, a finite verb can

stand by itself in a sentence.) Finite verbs are sometimes called main verbs or tensed

verbs. A finite clause is a word group that contains a finite verb form as its central element.

In "An Introduction to Word Grammar," Richard Hudson writes:

"The reason finite verbs are so important is their unique ability to act as the sentence-root. They

can be used as the only verb in the sentence, whereas all the others have to depend on some

other word, so finite verbs really stand out."

Finite vs. Nonfinite Verbs

The main difference between finite verbs and nonfinite verbs is that the former can act as the

root of an independent clause, or a full sentence, while the latter cannot.

For example, take the following sentence:

The man runs to the store to get a gallon of milk.

"Runs" is a finite verb because it agrees with the subject (man) and because it marks the tense

(present tense). "Get" is a nonfinite verb because it does not agree with the subject or mark the

tense. Rather, it is an infinitive and depends on the main verb "runs." By simplifying this

sentence, we can see that "runs" has the ability to act as the root of an independent clause:

The man runs to the store.

Nonfinite verbs take three different forms—the infinitive, the participle, or the gerund. The

infinitive form of a verb (such as "to get" in the example above) is also known as the base form,

and is often introduced by a main verb and the word "to," as in this sentence:

He wanted to find a solution.

The participle form appears when the perfect or progressive tense is used, as in this sentence:

He is looking for a solution.

Finally, the gerund form appears when the verb is treated as an object or subject, as in

this sentence:

Looking for solutions is something he enjoys.

Examples of Finite Verbs

In the following sentences (all lines from well-known movies), the finite verbs are indicated in

bold.

"We rob banks." — Clyde Barrow in "Bonnie and Clyde," 1967

"I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice chianti." — Hannibal Lecter in "The

Silence of the Lambs," 1991

"A boy's best friend is his mother." — Norman Bates in "Psycho," 1960

"We want the finest wines available to humanity. And we want them here, and

we want them now!" —

"You know how to whistle, don't you, Steve? You just put your lips together

and...blow." — Marie "Slim" Browning in "To Have and Have Not," 1944

"Get busy living, or get busy dying." — Andy Dufresne in "The Shawshank

Redemption," 1994

Identify Finite Verbs

In "Essentials of English," Ronald C. Foote, Cedric Gale, and Benjamin W. Griffith write that

finite verb "can be recognized by their form and their position in the sentence." The authors

describe five simple ways to identify finite verbs:

1. Most finite verbs can take an -ed or a -d at the end of the word to indicate time in the

past: cough, coughed; celebrate, celebrated. A hundred or so finite verbs do not have

these endings.

2. Nearly all finite verbs take an -s at the end of the word to indicate the present when the

subject of the verb is third-person singular: cough, he coughs; celebrate,

she celebrates. The exceptions are auxiliary verbs like can and must. Remember that

nouns can also end in -s. Thus "the dog races" can refer to a spectator sport or to a fastmoving third-person singular dog.

3. Finite verbs are often groups of words that include such auxiliary verbs as can, must,

have, and be: can be suffering, must eat, will have gone.

4. Finite verbs usually follow their subjects: He coughs. The documents had

compromised him. They will have gone.

5. Finite verbs surround their subjects when some form of a question is

asked: Is he coughing? Did they celebrate?

Predicators

In clauses and sentences, the predictor is the head of a verb phrase. The predicator is

sometimes called the main verb. Some linguists use the term predicator to refer to

the whole verb group in a clause.

Examples and Observations

Here are a few examples of the predictor found in pop culture and literature:

"What can occur in a clause is very largely determined by the predicator. For example,

it is a crucial property of the verb like that it permits occurrence of an object (indeed, it

normally

requires

one

in

canonical

clauses)."

"The predicator is the central syntactic element in a sentence. This is the case because

it is the predicator which determines the number of complements that will occur and,

indeed,

whether

a

particular

element

is

a

complement

or

an adjunct."

"She runs the gamut of emotions from A to B."(Dorothy Parker, in a review of a theater

performance by Katharine Hepburn)

"I left the

woods

for

as

good

a

reason

as

I went there."

(Henry David Thoreau, Walden, 1854)

Essential and Nonessential Sentence Elements

"Traditionally, the single independent clause (or simple sentence) is divided into two

main parts, subject and predicate. . . . The predicate can consist entirely of

the Predicator, realized by a verbal group, as in 1 below, or the Predicator together

with

one

or

more

1.

other

elements,

The

as

in 2:

plane landed.

2. Tom disappeared suddenly after the concert. It is the predicator that determines

the number and type of these other elements. Syntactically, the Subject (S) and the

Predicator

(P)

are

the

two

main

functional categories.

"The two clause elements in 1, the Subject (the plane) and the Predicator realized by

the verb landed are essential constituents. In 2 on the other hand, the predicate contains

as well as the predicator (disappeared), two elements, suddenly and after the concert,

which are not essential for the completion of the clause. Although they are to a certain

extent integrated in the clause, they can be omitted without affecting the acceptability

of

the

clause.

Such

elements

will

be

called Adjuncts (A)."

(Angela Downing, English Grammar: A University Course, 2nd ed. Routledge, 2006)

Predicators and Subjects

"The predicator has a fairly straightforward definition. It consists only of verbal

elements: an obligatory lexical verb and one or more optional auxiliary verbs. In

addition, only these elements can function as predicator, and they cannot have any

additional functions. Subjects, however, are more varied in form--they can be noun

phrases or certain types of clauses--and these forms can have other functions as well:

noun phrases, for instance, can also function as objects, complements, or adverbials.

For this reason, subjects are defined in terms of their position in a clause and their

relation to the predicator." (Charles F. Meyer, Introducing English Linguistics.

Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Functions of the Predicator

"[I]n addition to its function to specify the kind of process of the clause,

the Predicator has three other functions in the clause:

1. it adds time meanings through expressing a secondary tense: for example, in have been going

to read the primary tense (have, present) is specified in the Finite, but the secondary tense (been

going

to)

is

specified

in

the

Predicator.

2. it specifies aspect and phases: meanings such as seeming, trying, helping, which colour the

verbal

process

without

changing

its

ideational

meaning.

3. it specifies the voice of the clause: the distinction between active voice and passive voice

will be expressed through the Predicator."