Developing Internal Energy for Effective Acupuncture Practice Zhan Zhuang, Yi Qi Gong and the Art of Painless Needle Insertion ( PDFDrive )

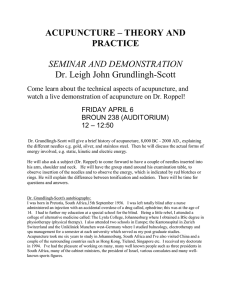

advertisement