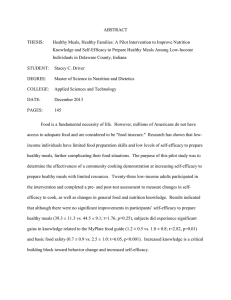

Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS Self-Efficacy: The Impacts of Wilderness Therapy on Urban Adolescents Morgan G. Miller University of Montana- COUN 545 1 Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 2 Abstract Within the U.S. population of 13-18-year old’s, 22.2% meet the criteria for severe distress or impairment (Gabrielsen & Harper, 2018). Additionally, an urban upbringing can exacerbate these mental health concerns in the adolescent population (Gabrielsen et al., 2018). That being said, urban adolescents are at exceptionally high risk for low levels of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy serves as a major protective factor for adolescents in general and can result in life-long mental health implications if not attended to. This study examines the impacts of wilderness therapy on levels of self-efficacy among urban adolescents. The two sample groups of urban and rural adolescents will have 20 participants each. It is predicted that the urban group will show a greater increase in self-efficacy over the rural sample. This study utilizes an eight-week wilderness therapy intervention to compare the difference in levels of self-efficacy from pretest to posttest. Conclusions and recommendations for future research are provided. Keywords: self-efficacy, adolescent, urban, wilderness therapy Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS Self-Efficacy: The Impacts of Wilderness Therapy on Urban Adolescents Self-efficacy is a pivotal factor in the personal success’s and development of all people. Self-efficacy is important for every age group, however its presence or lack thereof in the turbulent time of adolescence can be a heavy predictor of one’s long term health (Tabak & Zawadzka, 2017). Adolescent self-efficacy serves as an important protective factor for preserving and/or protecting the mental health of young people (Tabak et al, 2017). Some of the other benefits linked to self-efficacy in adolescence include, the varying health benefits, academic achievement within the high school years, and the association “with health promotion intentions and knowledge” (Margalit & Ben-Ari, 2014, p. 183). The positive impacts of wilderness therapy on youths levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy have already been established within the research (Harper, Russell, Cooley, & Cupples, 2007). The purpose of this study is to examine how utilizing wilderness therapy will impact levels of self-efficacy among urban adolescents over their rural counterparts. Mental Health of Adolescents According to Tabak and Zawadzka and WHO, mental health is described as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community…” (Tabak et al., 2017, p. 4). Tabak and Zawadzka highlight the severity of the mental health epidemic stating that WHO’s data indicates one third of the population is affected by mental health disorders every year (Tabak et al., 2017). Children and adolescents make up 20% of that one third of people needing assessment and intervention (Tabak et al., 2017). Additionally, in American adolescents the incidence of a major depressive episode went from 8.7% to 12.5% between 2005 and 2015, further demonstrating the prevalence and demand 3 Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 4 for treatment (Gabrielsen et al., 2018). An ever more disparaging statistic found that in the U.S. 22.2% of teens ages 13-18 meet the criteria for severe distress or impairment ranging from 14% with mood disorders, 31.9% with anxiety, and 19.1% with behavioral disorders (Gabrielsen et al., 2018). Adolescence can often be a confusing, and stressful transition for many young people. This time period marks many changes on a biopsychosocial level. The adolescent brain is growing and changing at a speed that makes teens particularly vulnerable to social influences and cues (Chervonsky & Hunt, 2019). Some of the most notable shifts for this developmental stage includes a heightened attention on peer to peer interaction, friendship building, increased experiences with bullying, and a growing need for autonomy (Chervonsky et al., 2019). That being said, it is estimated of the adults with mental health disorders, half of them experience the onset of disorders in adolescence (Tabak et al., 2017). Researchers Chattopadhyay and Mukhopadhyay further stress the impact of mental health disorders and adolescence in their study in which the primary objective was to assess and examine the mental health status and level of self-efficacy of 20 participants identified as at risk for developing depression. Chattopadhyay and Mukhopadhyay findings reinforce Tabak & Zawadzka’s by statings that “Half of lifetime diagnosable mental health disorders starts by age 14, this number increases to three fourths by age 24” (Chattopadhyay & Mukhopadhyay, 2011, p. 148) Urban youth and mental health Gabrielsen and Harper’s study on the role of wilderness therapy for adolescents in the face of global trends of urbanization and technification (2018) provides limited and valuable insight on urban youth. The study points out that in the last 10 years the number of people cohabiting in urban areas has exceeded the population of people living in rural environments Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 5 (2018). Additionally, that statistic is said to change by 2050, with a whopping 84% on an urban global scale (2018). This particular study defines urban areas as those referring to towns, suburbs and cities with a high density of man-made structures (2018). There is ample research examining the impact of urban upbringing on mental health. According to Gabrielsen and Liev the negative mental health repercussions include schizophrenia, mood disorders, anxiety, and a reduced ability to process social stressors (2018). Gabrielsen and Liev further illuminate the deficits of urban living for teens, when they point out that urbans settings rarely present themselves with environments or opportunities that foster serenity and presence of mind. These emotional states are facilitators of “self-awareness, introspection and contact with one’s emotional system, all key factors for making congruent and health-promoting adjustments to one’s life (McGeeney, 2016)” (2018, p. 412). Self- Efficacy Self-efficacy is defined as an individual's ability to organize and act on tasks required to yield an identified accomplishment or achievement (Tabak et al., 2017). Many consider it an essential inner resource and a factor in determining one’s health (Tabak et al., 2017). It is a known protective factor against symptoms of depression, (Chattopadhyay et al., 2011), stress (Tabak et al., 2017), and anxiety (Bai, Kohli, & Malik, 2017). It contributes to the prevention of other mental health issues in adolescence, and is linked to subjective feelings of happiness, a sense of well-being, and the perceived feeling of having social support (Tabak et al., 2017). Selfefficacy in teens is known to promote to pro-social behaviors, civic engagement, and increase the propensity for academic success (Tabak et al., 2017). One of the primary roles self-efficacy plays that inherently influences all the aforementioned characteristics pertains to decision making (Bai, et al., 2017). Levels of self- Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 6 efficacy are linked to one’s decision making skills, and how one approaches problems (Bai et al., 2017). Ones self-efficacious beliefs are what control “human functioning through cognitive, motivational, affective and decisional processes (Bandura, 1997)” (Tabak et al., 2017, pp. 3-4). These processes influence whether a person perceives their own abilities in ways that are either enhance or debilitate hinder the self (Tabak et al., 2017). This in turn, affects their emotional well-being, their aptitude to for perseverance when faced with difficult situations, and the ultimately the decisions or choices they make in those difficult situations (Tabak et al., 2017). Bai, Kohli, and Malik’s explorative study on mental health and its relationship between selfefficacy and hope among female college students provided further insight on the conceptualization of self-efficacy. In particular, that one’s level of self-efficacy dictates the likelihood that they will rise to a challenge. A person with high levels of self-efficacy are more likely to concede a challenge, while those with low levels are prone to evade perceived challenges (Bai et al., 2017). Researchers also found that those with high levels of self-efficacy attribute their failures to unfavorable environments or situations or a lack of effort or energy of their own doing (Bai et al., 2017). Conversely, those with low levels of self-efficacy attribute failure to a perceived deficiency in ability and are likely to lose confidence in their ability to achieve (Bai et al., 2017). When examining success, those with high levels are able to acknowledge that their achievement is a result of their ability, while those with low levels are prone to credit luck or external factors for their achievement (Bai et al., 2017). Wilderness Therapy The current literature on wilderness therapy suggests that there are a variety of ways to define treatment and inconsistent information around the origins of the practice. According to Margalit and Ben-Ari, wilderness therapy (WT) originated in the 1920’s and was intended to Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 7 serve as a rehabilitation program for at risk adolescents (2014). Kurt Hahn’s “Outward Bound” model originating in the 1940’s was the catalyst for the popularizing style of treatment. (Bastemur, 2019) Across the literature, the term wilderness therapy (WT) is also known as and/or synonymous with terms such as adventure- based counselling, adventure therapy, outdoor behavioral healthcare, wilderness experience programs, wilderness adventure therapy, bush adventure therapy, outdoor adventure intervention, and therapeutic camping (Bowen & Neill, 2013). WT has been described and characterized in a myriad of ways. With the primary focus being experiences that are typically in natural or outdoor environments that are intended to stimulate clients cognitively, behaviorally, and affectively (Bowen et al., 2013). Harper, Russell, Cooley, and Cupples add to the definition stating that WT merges outdoor recreational adventure, living, skill building and activities with both individual and group counseling (2007), (Bettmann, Tucker, Behrens, & Vanderloo, 2017). There are some fundamental characteristics of WT that distinguish it from other forms of therapeutic treatment. The first and most obvious characteristic is the inclusion and role nature plays in the therapeutic process, as well as “the use of perceived risk to heighten arousal and to create eustress (positive response to stress)” (Bowen et al., 2013, p. 28). Additionally, the inclusion of the process of kinesthetic learning, or “meaningful engagement” (Bowen et al. 2013, p.28) The literature on this topic highlight broad range of beneficial therapeutic returns to the WT approach. Numerous studies have found that physical activity alone can reduce symptoms of depression (Chattopadhyay et al., 2011). Margalit and Ben-Ari point out that for teens in particular, having the outdoors as the therapeutic setting contributes to the healing process and plays off of the inherent tendencies of adolescents of self-disclosure and spontaneity (2014). Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS Their article also suggests that the model most WT programs are derived from naturally address the communication challenges many adolescents face and is influential in overcoming the inherent challenges associated with having limited communication skills such as the sharing of ones thoughts and feelings, and overall cognitive and emotional openness (2014). Bowen identifies the goals of WT as cultivating psychosocial skills, addressing psychological problems by increasing and enriching one’s psychological resilience or decreasing behavioral issues (2007). A particularly notable benefit of WT is its immunity to readiness for change (Bettmann et al., 2017). It has been shown that an adolescents readiness for change is not needed to still to successfully reduce mental health symptomology (Bettmann, et al., 2017),(Margalit, D. et al.). Wilderness therapy and self-efficacy Unfortunately, there seems to be limited literature on the mental health status of urban adolescents, and the effects of wilderness therapy on that specific demographic. This gap in the research provokes the question of the effects of WT on self-efficacy for urban adolescence. Though WT has been utilized with various demographics with a variety of issues, it’s primary target group is typically at risk adolescents. Its growing popularity with this demographic is impart due to the inherent logistical and financial limitations associated with WT such as length of treatment, and distance traveled to receive treatment (Harper, et al., 2007). Given the nuanced and experiential nature of WT, it is often an ideal fit for many adolescents in the acquisition of self-efficacy. Just by being in an unfamiliar environment that requires the building of new skills and approaches to new challenges they are likely unaccustomed to, makes it a high predictor of increased self-efficacy. Margalit and Ben-Ari share that the promotion of self-efficacy can be addressed by WT because it gives teens situations and opportunities to engage triumphantly in varying activities that present as 8 Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 9 challenges (2014). Furthermore, engagement in WT is influential in the promotion of selfefficacy and is shown to increase levels of self-efficacy and self-concept following the participation in WT (Margalit et al., 2014). Self-efficacy and autonomy are the fundamental developmental markers of the decision-making process for adolescents. (Margalit et al., 2014) Therefore, there is significant worth in participation of WT because it promotes cognitive autonomy and self-efficacy and imposes valuable implications for preventing the participation in risky behaviors as well as cessation of said behaviors (Margalit et al., 2014). Additionally, Margalit and Ben-Ari found that group work within the context of WT promotes opportunity for teens to actively help one another, which in turn increases their self-esteem and self-efficacy (2014). Russell and Walsh, and Margalit and Ben-Ari’s studies provide the most evidence supporting the idea that WT increases self-efficacy. Margalit and Ben-Ari’s study specifically examined the effect of WT programs had on teens self-efficacy and cognitive autonomy (2014). Their study’s sample size was comprised of 93 at risk adolescent males ranging in age from 1416 that attended boarding schools in Israel (2014). Participants either participated in either a fulllength WT intervention, a partial WT intervention or a control condition, however random assignment did not occur (2014). Their findings exhibited that the participants in the full-length intervention showed a significant increase in the desired outcome of cognitive autonomy and self-efficacy over those who were in the partial participation group (2014). Russell and Walsh’s exploratory study of wilderness adventure programs for young offenders in Minnesota also found legitimate evidence supporting the efficacy of self-efficacy in WT. Their study was comprised of 33 males and 10 females (mean age =15) of which 60% were white, and 40% were considered non-white. In the analysis of the study, their results confirmed Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 10 what the literature already supports, showing a significant increase in self-efficacy (Russell & Walsh, 2011). Purpose of study The research on wilderness therapy is limited and lacking, however it appears that there is a general consensus among the bodies of work that WT is beneficial for general well-being and increases self-efficacy. Unfortunately, as stated earlier, there appears to be little to no research done on the efficacy of wilderness therapy on the specific demographic of adolescents growing up in urban areas, despite a demand for mental health services among this demographic. Furthermore, Bettmann points out the limited information on specific gender differences among WT participants (2017), and Neil and Bowen’s metanalysis of WT studies found limitations with regards to the availability of studies overall generalizability, heterogeneity, and “type of data provided by empirical studies, and the methodological quality of studies” (2013, p. 41). The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between self-efficacy and wilderness therapy and its potential impacts on urban youth. The research question guiding this investigation is, does wilderness therapy have a more significant impact on urban youth’s selfefficacy as compared to rural youth’s self-efficacy? I hypothesize self-efficacy will significantly increase with the implantation of wilderness therapy for adolescents ages 13-18. This increase will be more significant for urban youth over rural youth. Methods Participants This experiment will be comprised of 40 adolescents varying in ages from 13 to 18. Fifty percent of the study’s participant pool will be made up of adolescents who have been raised in and are still currently living in urban areas across the United States. Conversely, the other 20 Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 11 participants will be made up of adolescents who have been raised in and are currently still living in rural settings across the United States. For the sake of this study, urban will be defined as a city with a population over 800,000 people with a minimum density of 1,000 people per square mile. Rural will be defined as towns with less than 10,000 people with a population density of 500 people per square mile. For the process of selecting participants in an urban area, the top ten most populated cities in the United States were identified and selected with the exclusion of cities in the same state to provide a more diverse spread of participants. Rural adolescents will not be targeted by region however will need to meet the requirements of rural living. The rural participants will also vary, having 20 different people from ten different states. Participants will be recruited through multiple social media platforms. Advertisements will be intended to target both adolescents and parents. The recruitment approach paired with the spread of cities and towns from at least 10 different states will yield a comprehensive representative group in regard to gender, age, education, ethnicity and socioeconomic status of America’s urban and rural adolescents. Some preliminary screenings to the sample group will be necessary given the nature of the experiment. Applicants will need to meet the urban and rural living requirements, as well as the age requirement. Both groups (urban and rural) will have no more than ten participants that identify as the same gender. As an example, of the 20 rural participants, no more than ten participants will identify as female, male, or gender non-conforming. Exclusionary criteria for the experiment may also include psychosis, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. Additionally, adolescents with conduct disorders or with a history of violence or sexual assault will be unable to participate. Physical limitations, such as a reliance on Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 12 a wheelchair or crutches, or any problem requiring prolonged or intensive medical care or monitoring like eating disorders severe enough to require a feeding tube, diabetes, and postural tachycardia syndrome may also be unfit for the study. Participants will be offered a $100 incentive for their participation in the experiment, with $50 being given upon completion of the initial pre-test assessment and the additional $50 being given after the WT trip upon completion of the post-test assessment. All participants and their parents go will go through a formal informed consent process. Though consent will be required of parents or legal guardians of the participants, assent from the participants themselves will be necessary for participation as well. Instrumentation Chen et al.’s New General Self-Efficacy Scale (NGSE). Developed in 2001, Chen’s New General Self-Efficacy Scale aligns itself with the definition of general self-efficacy: “one’s belief in one’s overall competence to effect requisite performance across a wide variety of achievement situations” (Scherbaum, et al., 2006, p. 1050). The assessment is quite brief, and typically takes about three minutes to complete on average (Stanford SPARQtools, n.d.). This particular scale is made up of eight statement items using a five-point rating scale. The rating scale is broken down as 1= Strongly Disagree, 2= Disagree, 3= Neither Agree Nor Disagree, 4= Agree, and 5= Strongly Agree. Examples of the eight statement items include “I will be able to successfully overcome many challenges” (Stanford SPARQtools, n.d.) and “I will be able to achieve most of the goals that I set for myself” (Stanford SPARQtools, n.d.). Higher scores indicate higher levels of general self-efficacy (Scherbaum, et al., 2006). Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 13 Scherbaum, et al. states that for this particular measuring tool the preliminary psychometric evidence fairs well (2006). Additionally, the internal consistency of the responses to the items featured in the assessment are fairly high for exploratory research (Scherbaum, et al., 2006). The cutoff for exploratory research for internal consistency is .70 while Chen’s et al. ranges from .85 to .90 (Scherbaum, et al., 2006). Going further, Scherbaum, et al. states that the stability coefficient raging from r= .62 to r=.65 are fairly high for “trait-like individual difference variables” (2006, p. 1051). Procedure Upon meeting the preliminary requirements, and giving informed consent and assent, applicants names will be placed into two groups based on their urban or rural upbringing. Names will be pulled at random. No more than two participants from the same grouping (urban or rural) can be from the same state thus if a third name from the same state is selected it will be discarded. Additionally, if ten applicants who identify as male, female, or gender nonconforming from either group have already been selected, any further selections from that same group will also be discarded. Once the selection process is complete, the New General Self-Efficacy Scale will be administered in a group setting on the first day of the program. All participants will then embark on a eight week empirically based wilderness therapy program called Second Nature. Participants will partake in the Utah based program that identifies self-efficacy as a primary focus. The clinical director and facilitator of the program has been quoted on the American Physiological Association website as stating that "A big part of this experience is helping students experience for themselves a greater sense of self-efficacy and internal locus of control” (DeAngelis, 2013, p. 48). Staffed by three doctoral level psychologists and five more mental Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 14 health professionals the program will utilize evidence-based practices to treat all 40 participants on an identified goal. Upon completion of the program, participants will take a post-test utilizing the same measurement scale. Statistical Analysis An ANOVA will be used to compare changes in mean scores of the two groups from pretest to post-test (p < .05). Results It is expected that rural and urban samples will have significantly different levels of selfefficacy after the eight-week wilderness therapy program. Self-efficacy scores for the rural group will be (μ=2.45) at baseline while self-efficacy scores for the urban group will be (μ= 2.40) at baseline. Self-efficacy scores post intervention for the rural group will be (μ = 3.95) at post-test. Self-efficacy scores post intervention regarding the urban group will be (μ = 4.65) at post-test (See Figure 1.1 for chart). This statistical differences between groups will be analyzed using ANOVA. While both groups are expected to increase in levels of self-efficacy, it is expected that significant differences will exist between the two groups (p < .005) with the urban group showing a greater increase over time compared to the rural group. The results show that the average NGSE mean score increased 1.5 points for rural participates and 2.25 points for urban participants. Therefore, the results confirm the hypothesis that the urban participants gained more self-efficacy over time than their rural counterparts. Discussion The results of this study are anticipated to indicate that WT will be more effective in increasing levels of self-efficacy among urban adolescents over rural adolescents. These results Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 15 will help lay the foundation for research regarding effective practices for increasing self-efficacy through WT for urban youth. Community outreach programs, school curriculum, and summer camps could be developed incorporating the findings of this study. Utilization of evidence-based practices would enhance the advocacy and outreach efforts of community organizations and provide support for funding requests and applications for grants. Additional tests on the data would be useful to explore correlations between environment, demographic and changes in self-efficacy based on variables such as age, gender, family background, family income, etc. Indicators might be identified that could inform more focused follow-up interventions for change. It is expected that urban participants will start with lower levels of self-efficacy as compared to rural participants, however, finish the intervention with a larger increase in self-efficacy levels than their rural counterparts. In regards to gender it is expected that female participants will demonstrate more change in their self-efficacy compared to male participants. There are some major limitations of the study that are pertinent to include within this section. One of the primary limitations to this study and other WT studies is the fairly exhaustive list of exclusionary criteria. This list includes excluding applicants that suffer from psychosis, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. Adolescents with conduct disorders or with a history of violence or sexual assault. Applicants with physical limitations, such as a reliance on a wheelchair or crutches, or any problem requiring prolonged or intensive medical care or monitoring like eating disorders severe enough to require a feeding tube, diabetes, and postural tachycardia syndrome may also be unfit for the study. Another limitation to consider is low SES participants may be relied on as an additional resource in their homes. These resources could include providing free child-care for younger Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 16 siblings, contributing financially to the family income or fulfilling the role of second parent. Serving this role may have prevented many from volunteering for the study and subsequently may have impacted the sample of urban youth involved. Limitations may also include the consideration that eight weeks is a long period of time where any unknown event could take place to disrupt the study. Lastly, maturation could affect the outcome of the study since students are still growing and maturing given the age of participants. Further research is needed to confirm the expected results and extend them with inclusion of categories beyond just urban and rural adolescents. This study could be continued by monitoring the participants into adulthood to see what happens to levels of self-efficacy over time and how that impacts their levels of academic and professional success. Will their levels of self-efficacy be sustained, increase, or decrease in the years after the intervention? Further studies on how much or little WT is needed to increase self-efficacy and how to implement that in more urban school settings would be beneficial. Furthermore, researching specifically what about WT increases self-efficacy and harnessing that for more wide-spread application in a more accessible way could undoubtably serve to be valuable. Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 17 References Baştemur, Ş. (2019). Adventure Therapy. Psikiyatride Guncel Yaklasimlar, 11(2), 178-190. doi:http://dx.doi.org.weblib.lib.umt.edu:8080/10.18863/pgy.434071. Bai, K., Kohli, S., & Malik, A. (2017). Self-efficacy and hope as predictors of mental health. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(4), 631-635. Retrieved from https://searchproquest-com.weblib.lib.umt.edu:2443/docview/1986584611?accountid=14593. Bettmann, J., Tucker, E., Behrens, A., & Vanderloo, E. (2017). Changes in Late Adolescents and Young Adults’ Attachment, Separation, and Mental Health During Wilderness Therapy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(2), 511-522. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0577-4. Bowen, D. J., & Neill, J. T. (2013). A meta-analysis of adventure therapy outcomes and moderators. The Open Psychology Journal, 6(26), 28-53. doi:http://dx.doi.org.weblib.lib.umt.edu:8080/10.2174/1874350120130802001 . Chattopadhyay, S., & Mukhopadhyay, A. (2011). Self-efficacy and mental health measures of adolescents with depression ‘at risk’ and vulnerable depressives. Indian Journal of Community Psychology, 7(1), 147-154. Retrieved from http://www.ijcpind.com/wpcontent/uploads/2011/12/cpai_march2011.pdf#page=147. Chervonsky, E., & Hunt, C. (2019). motion regulation, mental health, and social wellbeing in a young adolescent sample: A concurrent and longitudinal investigation. Emotion, 19(2), 270-282 doi:http://dx.doi.org.weblib.lib.umt.edu:8080/10.1037/emo0000432 . Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 18 Gabrielsen, L. E., & Harper, N. J. (2018). The role of wilderness therapy for adolescents in the face of global trends of urbanization and technification. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 23(4), 409-421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2017.1406379. Harper, N. J., Russell, K. C., Cooley, R., & Cupples, J. (2007). Catherine freer wilderness therapy expeditions: An exploratory case study of adolescent wilderness therapy, family functioning, and the maintenance of change. Child & Youth Care Forum(36), 111–129. Margalit, D., & Ben-Ari, A. (2014). The effect of wilderness therapy on adolescents’ cognitive autonomy and self-efficacy: Results of a non-randomized trial. Child & Youth Care Forum, 42(2), 181-194. doi:http://dx.doi.org.weblib.lib.umt.edu:8080/10.1007/s10566013-9234-x . McGeeney, A. (2016). With Nature in Mind: The Ecotherapy Manual for Mental Health Professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley. Russell, K. C., & Walsh, M. A. (2011). An Exploratory Study of a Wilderness Adventure Program for Young Offenders. Journal of Experiential Education, 33(4), 398-401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/105382591003300415. Scherbaum, C. A., Cohen-Charash, Y., & Kern, M. J. (2006). Measuring general self-efficacy: A comparison of three measures using item response theory. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(6), 1047-1063. doi:http://dx.doi.org.weblib.lib.umt.edu:8080/10.1177/0013164406288171 Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS 19 Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35-37). Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson. Tabak, I., & Zawadzka, D. (2017). The importance of positive parenting in predicting adolescent mental health. Journal of Family Studies, 23(1), 1-18 doi:http://dx.doi.org.weblib.lib.umt.edu:8080/10.1080/13229400.2016.1240098. Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35-37). Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson. Running head: SELF- EFFICACY: THE IMPACTS OF WILDERNESS THERAPY ON URBAN ADOLECENTS New General Self-Efficacy Mean Scores Figure 1.1 5 4,5 4 Mean Average 3,5 3 2,5 2 1,5 1 0,5 0 Pre-Test (μ) Rural Group Post-Test (μ) Urban Group Figure 1.1. Mean scores from the rural participants of and urban participants respectively demonstrating the change from pretest to posttest on their general levels of self-efficacy on the using the New General Self-Efficacy Scale 20