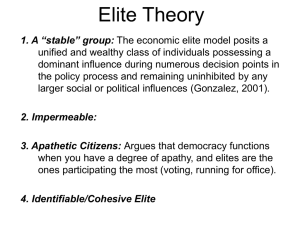

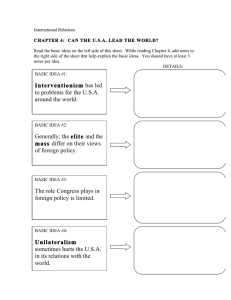

Power and Authority PO107 Week 5 The key to political science. Analysis of the ‘nature, exercise and distribution of power’ (Max Weber 1919) “Politics is about more than what governments choose to do or not to do; it is about the uneven distribution of power in a society, how the struggle for power is conducted, and its impact on the creation and distribution of resources, life chances and well-being” — Gerry Stoker and David Marsh, Theory and Methods in Political Science The plan 1. What is ‘power’ ? 2. The three ‘faces’ of power 3. Theories of power (Elitism, Pluralism, Marxism) 4. The dilemma of authority 1. What is ‘power’ ? Defining power Whose power? 1. Power of individuals 2. Power of institutions (Comparative Pol) 3. Power of states (IR) 4. Structural Power (Critical) Which aspect of power? 1. Exercising power 2. Distribution of power 3. Sources of power 4. Consequences of power An ‘essentially contested concept’ Classic definitions “Actor ‘A’ has power over actor ‘B’ to the extent that she can get actor ‘B’ to do something that he would otherwise not do” — Robert A. Dahl. 1957. ‘The Concept of Power’, Behavioural Science 2, 201 Example: Keir Starmer can get Rishi Sunak to hold an early general election, which Rishi Sunak would not otherwise do since the Conservatives are trailing Labour in opinion polls ‘Power-over’ ‘Power-to’ “In general, we understand by ‘power’ the chance of a man or of a number of men to realize their own will in a communal action even against the resistance of others who are participating in the same action” — Max Weber, ‘Economy and Society’, 1968 (1922) ‘Power-to’ Problem 1: Effects may be incidental e.g., B may be following own interests Problem 2: Power can have unintended effects e.g., Theresa May’s decision to call a general election and blow up her majority Problem 3: Context is important Power is provisional, conditional and relative e.g., boss and you at work and in pub; US president (absolute power) vs. UK Prime Minister (relative power) Problem 4: Power can be latent Easier to measure when it is being exercised 2. The ‘three faces of power’ Stephen Lukes (1974) ‘Power: A Radical View’ Builds on Peter Bachrach and Morton S. Baratz (1962) The Two Faces of Power, American Political Science Review 57: 948 1. Decision-making 2. Agenda setting (non decision-making) 3. Preference shaping The lower we get on the list, the more important the power becomes? The first face of power: decision-making Overt/directly observable – the power to make or influence decisions (see Dahl etc.) Example: If a committee has voted on an issue (e.g., build nuclear power plant) the side that won would be said to have exerted power Second face of power: agenda setting Non decision-making – keeping items OFF the political/voting agenda Issues that are never actually available for discussion, do not feature in observable process Agenda setting power “[agent] A devotes his energies to creating or reinforcing social and political values and institutional practices that limit the scope of the political process to public consideration of only those issues which are comparatively innocuous to A” — Peter Bachrach and Morton S. Baratz (1962) ‘The Two Faces of Power’, American Political Science Review 57: 948 Mobilisation of bias ‘All forms of political organization have a bias in favor of the exploitation of some kinds of conflict and the suppression of others because organization is the mobilization of bias. Some issues are organized into politics while others are organized out’ — E.E. Schattschneider (1960) The Semi-Sovereign People Example: In vote on nuclear power plant, alternative sources of power (e.g., wind, solar) might not have been on the agenda. The third face of power: preference shaping Decisions can be affected by wider structural and ideational sources of power Structured ideas influence how we think about political possibility ... and our ability to question Michel Foucault: Forms of power can be internalised and routinised Example: Stopping at red light without thinking about it Preferencing shaping power “Is it not the most insidious exercise of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions, and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things, either because they can see or imagine no alternative to it, or because they see it as natural or unchangeable, or because they value it as divinely ordained and beneficial?” Steven Lukes (1974) Power: A Radical View 3. Theoretical perspectives on power Elite theory Pluralsim Marxism Elite theory 1. Power is concentrated (in an elite) 2. Elites are drawn from a narrow stratum 3. Elites circulate Classical and Modern variants Classical elite theory Different ‘kinds’ of people: ‘Leaders (technical or organisational skills) & Followers (apathic; psychological need for leadership)’ Rule by the few due to some innate qualities Robert Michels (1911) Political Parties Critiques of classical elite theory 1. Methodological individualism An overemphasis on the role of individuals (in this case the psychological sources of power) and ignoring structural forms of power and/or contexts 2. A lack of empirical evidence The existence of an elite was largely just assumed Modern Elite Theory (1940s+) Power derived from structural position in society (not from personal qualities) Formal political authority vs. ‘real’ (economic) power Economic power: behind the scenes (not visible to the public) Empirical research (two important examples) Floyd Hunter (1953) – study local Atlanta politics Based on the ‘reputational method’: ask people to nominate those they felt were most power in their city) Identified a, largely business based, ‘power elite’ (around 40 people) Findings subsequently replicated by others in several U.S. cities C Wright Mills (1956) – national level US ‘Power elite’ operated in U.S. nation as whole Interlocking economic, political & military elites Eisenhower ‘iron triangles’ / military-industrial complex Ideas extend to other countries Notion of British elite around Westminster and the City, public school system, Oxbridge, etc.) Critique 1: Accuracy/Where the boundaries? Is reputation an accurate indicator of who has power? Why 40 people? Context? Critique 2: How to study an elite? Can a researcher gain access to behind the scenes power? Critique 3: Non-falsifiable (‘infinite regress’) Just because analysis doesn’t identify elites, doesn’t mean they are not there ... Pluralism (1960s) For the most part still dominant view today. 1. Power is dispersed throughout society 2. Politics is competitive – different interest groups 3. Policy is the outcome of competitive processes Focus on directly observable power. Robert Dahl (1961): ‘Who Governs?’ Method: focus on actual decisions taken in New Haven No single group or organisation was said to dominate No elite group exists = polyarchy not oligarchy Structural factors? Neo-pluralists Take structure/nuance more into account: 1. Structural power of business – business does not need to ‘go to’ government 2. Closed networks / issues (e.g., foreign policy ‘closed’ ?) 3. Elite pluralism – i.e. no single elite Neo-problems 1. Circular reasoning: Q1 : How are decisions made? A1 : In the interests of the strongest groups. Q2 : Who are the strongest groups? A2 : Those in whose interests decisions are made. 2. Little recognition of structure beyond power of business Marxism Marx was one of the first to note structure–agency issue “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past” (Marx 1852) Economic system (captilasim) as the structural power Subsequent Marxists expanded on this to include other sources of power The power of ideas ‘Cultural hegemony’: some ideas so powerful that they do not need laws to uphold (third ‘face’) Therefore, confront power on the level of ideas Antonio Gramsci (1929-35) Prison Notebooks Problems with Marxism 1. Too deterministic (Althusser)? 2. Is capitalism really oppressive? 3. Outdated? Each approach highlights some of the subtleties of power that the other approach might overlook 4. The dilemma of authority Power works in differrent ways, on different levels, through various ideological and cultural forms This is an important issue for politics and society Milgram experiment (1963, 1974) Tested people’s willingness to obey authority (‘legitimate power’) Example: The defence of many Nazis on trial after WW2 was that they were ‘just following orders’ The shocks got stronger and stronger, leading to a ‘fatal shock’ and the ‘death’ of the other person Two-thirds of people would follow orders up to the fatal dose. Interpretation Some horrific events less caused by deliberate evilness and more by suspension of imagination, thinking, reflection etc. But bebate, reason, persuasion are essential to the practice of ‘normal politics’ (Aristotle – week 2) Hence this suspension is a problem for politics The dilemma of authority 1. Obeying is needed for society to work and potentially evolutionary pre-programmed 2. But it has potentially dangerous consequences “We do not observe compliance to authority merely because it is a transient cultural or historical phenomenon, but because it flows from the logical necessities of social organization. If we are to have social life in any organized form—that is to say, if we are to have society—then we must have members of society amenable to organizational imperatives” — Letter from Stanley Milgram, 25 September 1973 Summary 1. Power is conditional, relative and contextual 2. The ‘three faces’ of power highlight some of these dimensions 3. Elite theory, pluralism, and Marxism conceive of power in different ways 4. Society needs authority, but too much can be dangerous