CBT for Anxiety & Depression: Evidence-Based Treatment

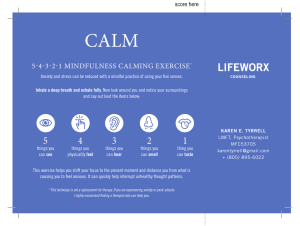

advertisement