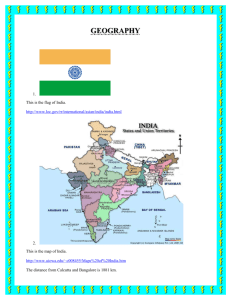

Annotate the following article below on the Ganges River. Highlight or underline phrases or sentences that have key/main ideas. Circle words that need defining. Write questions on the side when something isn't fully understood. In the boxes, write a one sentence summary of the passage. What It Takes to Clean the Ganges More than a billion gallons of waste enter the river every day. Can India’s controversial Prime Minister save it? By George Black, July 18, 2016 The Ganges River begins in the Himalayas, roughly three hundred miles north of Delhi and five miles south of India’s border with Tibet, where it emerges from an ice cave called Gaumukh (the Cow’s Mouth). Eleven miles downstream, it reaches the small temple town of Gangotri. Pilgrims cluster on the rocky riverbank. Some swallow mouthfuls of the icy water, which they call amrit—nectar. Women in bright saris wade out into the water, filling small plastic flasks to take home. Indians living abroad can buy a bottle of it on Amazon or on eBay for $9.99. The Ganges River has holy water that people can buy on Amazon or Ebay. To hundreds of millions of Hindus, in India and around the world, the Ganges is not just a river but also a goddess, Ganga, who was brought down to Earth from her home in the Milky Way by Lord Shiva, flowing through his dreadlocks to break the force of her fall. The sixteenth-century Mogul emperor Akbar called it “the water of immortality,” and insisted on serving it at court. In 1615, Nicholas Withington, one of the earliest English travelers in India, wrote that water from the Ganges “will never stinke, though kepte never so longe, neyther will anye wormes or vermine breede therein.” The myth persists that the river has a self-purifying quality—sometimes credited to sulfur springs, or to high levels of natural radioactivity in the Himalayan headwaters, or to the presence of bacteriophages, viruses that can destroy bacteria. Their is a myth between Hindus that their is a bacteria in the water that cleans it. Below Gangotri, the river’s path is one of increasing degradation. Its banks are disfigured by small hydropower stations, some half built The towering hydroelectric dam at Tehri, which began operating in 2006, releases a flood or a dribble or nothing at all. The first significant human pollution begins at Uttarkashi, seventy miles or so from the source of the river. Like most Indian municipalities, Uttarkashi—a grimy cement-and-cinder-block town of eighteen thousand—has no proper means of disposing of garbage. Instead, the waste is taken to an open dump site, where, after a heavy rain, it washes into the river. Below the river there's lots of garbage washed into the water. A hundred and twenty miles to the south, at the ancient pilgrimage city of Haridwar, the Ganges enters the plains. This is the starting point for hundreds of miles of irrigation canals built by the British, beginning in the 1840s, after a major famine. What’s left of the river is ill-equipped to cope with the pollution and inefficient use of water for irrigation farther downstream. The Ganges picks up the waste from sugar refineries, distilleries, pulp and paper mills, and tanneries, as well as the contaminated agricultural runoff from the great Gangetic Plain, the rice bowl of North India, on which half a billion people depend for their survival. By the time the river reaches the Bay of Bengal, more than fifteen hundred miles from its source, it has passed through Allahabad, Varanasi, Patna, Kolkata, a hundred smaller towns and cities, and thousands of riverside villages—all lacking sanitation. The Ganges absorbs more than a billion gallons of waste each day, three-quarters of it raw sewage and domestic waste and the rest industrial waste, and is one of the ten most polluted rivers in the world. The Ganges has a lot of pollution. Indian governments have been trying to clean up the Ganges for thirty years. Official estimates of the amount spent on this effort vary widely, from six hundred million dollars to as much as three billion dollars; every attempt has been undone by corruption and apathy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, elected in May of 2014, is the latest to try. Modi and his Hindu-nationalist party campaigned on promises of transforming India into a prosperous, vibrant modern society, a nation of bullet trains, solar farms, “smart cities,” and transparent government. Central to Modi’s vision is the Clean India Mission. He insists that rapid economic development and raising millions of people out of poverty need not come at the cost of dead rivers and polluted air. So far, however, the most striking feature of his energy policy has been the rapid acceleration of coal mining and of coal-fired power plants. In many cities, the air quality is hazardous, causing half a million premature deaths each year. Indian governments are trying to help clean up the river. Explain the relationship between the Ganges River and the people of India. Use supporting details from the pictures, video, and article. People see the Ganges River as holy water that helps purify them, but the water is very polluted and dirty.