Improving Reading Comprehension: Text Structure Instruction

advertisement

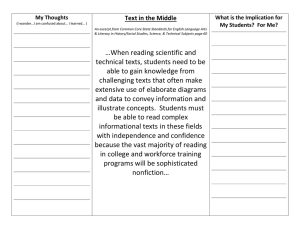

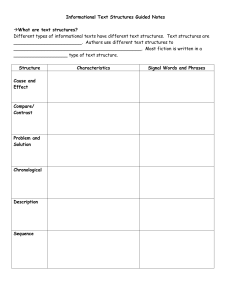

TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 232­–241. Copyright 2020 The Author(s). DOI: 10.1177/0040059919889358 Improving Reading Comprehension of Informational Text Text Structure Instruction for Students With or At Risk for Learning Disabilities Leah M. Zimmermann, M.Ed. , and Deborah K. Reed, Ph.D. Iowa Reading Research Center, University of Iowa 232 , the reading comprehension of students with or at risk for LD is text structure instruction. The ability to comprehend informational texts is critical to students’ academic success in a range of content areas. However, informational texts pose challenges to the reading comprehension of adolescents with or at risk for learning disabilities (LD). One such challenge is the use of multiple text structures in a single text. Text structure instruction, in which students learn to identify and analyze organizational patterns in texts, may improve the abilities of students with or at risk for LD to comprehend informational text. Importantly, text structure instruction must go beyond identifying a single overarching structure of a controlled exemplar text. To ensure that students with or at risk for LD experience rigorous text structure instruction aligned to grade-level standards, teachers need to implement instruction using authentic texts and carefully plan and gradually increase the relative complexity of instructional tasks. The purposes of this article are to describe explicit, scaffolded text structure instruction with authentic, multistructure informational texts and provide resources that general and special education teachers can use to scaffold text structure instruction. Ms. Grant is a ninth-grade special education teacher who supports students with learning disabilities (LD) in their English language arts (ELA) classes. During the first of a series of professional learning community meetings, Ms. Grant collaborated with her general education co-teacher, Mr. Robinson, to review recent student work, including reading comprehension quizzes and text-based writing assignments. They saw a pattern in which students were especially struggling with comprehending informational texts. The Grade 9 ELA team wanted to identify reading standards with which their students were having the most difficulty to develop reading comprehension instruction tailored to their students’ needs. They determined that many of their students with LD were struggling with CCSS.ELALITERACY.RI.9, a standard that relates to the organization and structures of the ideas conveyed in informational texts (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices [NGACBP] & Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO], 2010a). Ms. Grant and Mr. Robinson arrive at the second professional learning community meeting eager to work with the Grades 9–12 ELA team to design instruction on informational text structures and improve their students’ comprehension of informational texts. The ability to comprehend informational text is crucial to students’ academic success in a range of subject areas, including science and social studies (O’Connor et al., 2017; Reed, Petscher, & Truckenmiller, 2017). By the time that students reach middle school, collegeand career-readiness standards indicate that the majority of assigned texts used across the curriculum be informational texts (NGACBP & CCSSO, 2010a). The standards also require students to demonstrate their reading comprehension by analyzing and synthesizing elements of complex informational texts taken from a range of genres (e.g., memoirs, speeches, technical writing, essays; NGACBP & CCSSO, 2010c). Students with or at risk for LD may struggle with these text comprehension expectations for several reasons. They may have difficulty self-monitoring their comprehension as they read (Joseph & Everleigh, 2011). In addition, they may not have learned beneficial comprehension strategies or do not have the ability to apply learned strategies when comprehension breaks down (Hock, Brasseur-Hock, Hock, & Duvel, 2017). Furthermore, students with or at risk for LD may exhibit more comprehension difficulties when reading informational text than when reading literary text, particularly when attempting to make inferences (Denton et al., 2015). These difficulties may be attributable to specific challenges presented by informational Text Structure Instruction One type of strategy instruction that may improve the reading comprehension of students with or at risk for LD is text structure instruction (Hebert, Bohaty, Nelson, & Brown, 2016; Pyle et al., 2017). In text structure instruction, teachers explicitly teach students to identify and analyze structural elements using a range of strategies. Text structure instruction is one approach that can be implemented with students with or at risk for LD when reading informational texts. Text structure is the way that an author organizes the information in a text to achieve a specific purpose, such as to persuade or inform the reader (Meyer & Poon, 2001). Text structures that might be taught include cause-effect, description, problem-solution, and sequence (Meyer & Ray, 2011). For descriptions of the common text structures, see Figure 1. Importantly, students experience better outcomes when teachers provide instruction in a range of text structure types, rather than focusing on a singular high-leverage structure (Hebert et al., 2016). Being able to recognize common organizational patterns in informational texts may provide students with cognitive frameworks to organize the complex vocabulary and content encountered while reading (Pyle et al., 2017), thus supporting their comprehension as well as their retention and recall of important information (Hebert et al., 2016). Students need to not only identify text structures but also analyze how authors use structural elements to communicate their March/April 2020 “ One type of strategy instruction that may improve text. Informational texts often contain complex, domain-specific vocabulary and place high demands on students’ content knowledge (Gajria, Jitendra, Sood, & Sacks, 2007). Moreover, informational texts may organize ideas in a variety of ways, or text structures, that tend to change multiple times within and across paragraphs (Pyle et al., 2017). Fortunately, explicit reading comprehension strategy instruction, in which teachers model and provide scaffolded practice in using and selecting strategies for making meaning from text, has been found to benefit the reading comprehension of students with or at risk for LD (Boardman, Klingner, Buckley, Annamma, & Lasser, 2015). 233 234 Sequence: Listing in chronological order how an event or process occurs. Problem-Solution: Identifying a problem and possible solution(s) to the problem. Description: Identifying a topic and describing its characteristics and/ or features and/or providing relevant examples. Cause-Effect: Explaining causes and their resulting outcomes or effects. Compare-Contrast: Explaining ways in which two or more things are similar and different. Structure/Definition Step: How can the main event or process be broken up? How does the main event or process occur? In what order do the parts of the event or process occur? Solution: How can this problem be fixed or helped? Problem: What is going wrong? What is the conflict? Examples: What is an example of ____? Features: What is ____made up of? Characteristics: What is ____ like? Effect: What happened as a result of ____? Cause: What made ____ happen? What led to ____? Differences: What is different? How are ____ and ____ not the same? Similarities: What is the same? How are ____ and ____ alike? Elements/Guiding Questions F i g u r e 1 Text structure guide TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 52, No. 4 3. 2. 1. Map •• •• •• •• •• •• •• identify causes of problems identify effects of solutions identify causes and effects of events compare and contrast causes compare and contrast effects identify events that caused effects identify events that caused problems compare and contrast problems compare and contrast solutions identify causes of problems identify effects of solutions list steps of a solution sequence events that led to a problem compare and contrast events or processes identify causes and effects of events sequence events that led to a problem identify events that caused effects identify events that caused problems •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• conflict, harm, problem, problematic, issue, difficulty, crisis, jeopardy, challenge solve, fix, help, answer, resolve, ameliorate, support, recourse, improve, better, enhance, benefit first, second, third…, next, then, last, finally, initially, at the beginning, at the end, before, after, preceding, following, prior to, cycle, sequence, process, history characteristics, attributes, factors, •• describe characteristics of causes, effects, features, like, usually, often, problems, solutions, events, or processes consists of, comprise, composed •• provide examples of causes, effects, of problems, solutions, events, or processes for example, for instance, as an illustration, such as, in particular, specifically, to demonstrate, exemplifies because, since, consequently, led to, therefore, as a result, because, if/then, hence, thus, due to, since, accordingly, consequence, outcome, influence, impact contrast, different, however, but, on the other hand, although, though, yet, conversely, nevertheless compare and contrast problems compare and contrast solutions compare and contrast causes compare and contrast effects provide examples of similarities and differences •• compare and contrast events or processes same, similar, like, in the same way, compare, have in common, both, also, alike, by the same token, equally, just as •• •• •• •• •• Structure Partners Signal Words and Phrases found to improve the reading comprehension of students with or at risk for LD. intended messages (i.e., ideas or claims). Text mapping is a strategy that has been found to improve the reading comprehension of students with or at risk for LD (Boon, Paal, Hintz, & CorneliusFreyre, 2015; Pyle et al., 2017). A text map is a graphic organizer that students use to organize and display textual features and corresponding textual details (Gajria et al., 2007). For example, a simple table containing numbered rows might be used to display the chronological order of events in the sequence text structure. See Figure 1 for examples of text maps for common text structures. The maps provide a means for students to visualize structural elements and analyze their relationships to the ideas presented in the text. Therefore, text structure instruction often pairs the identification of text structures with the analysis of text structures in a text map. Most authentic informational texts are composed of multiple text structures (Meyer, 2003). Authentic texts are those that have been written to achieve a communicative purpose, rather than solely to teach students particular reading or writing skills (Duke, Purcell-Gates, Hall, & Tower, 2006). In text structure instruction, authentic texts can be contrasted with controlled exemplar texts, which are carefully crafted to exemplify particular text structures and their elements (e.g., Williams et al., 2016). Teachers use single-structure exemplar texts in the initial phases of text structure instruction (Jones, Clark, & Reutzel, 2016) and teach students strategies for analyzing particular structures, such as using a note frame to organize important information (e.g., Roehling, Hebert, Nelson, & Bohaty, 2017). Explicit instruction and practice with controlled exemplar texts may serve as a form of scaffolding to strengthen students’ mental representations of text structures (Meyer & Ray, 2011). However, it is crucial for subsequent instruction to incorporate increasingly complex Step 1: Prepare for the Lesson informational texts, such as those containing unfamiliar content knowledge or authentic texts composed of multiple types of text structures (Pyle et al., 2017). The ELA instructional coach, Ms. Thomas, suggests that the ELA team should help Ms. Grant and Mr. Robinson unpack CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.RI.9 into a progression of subskills that students must learn before mastering the grade-level standard. Next, Ms. Grant and Mr. Robinson review students’ quizzes and text-based writing assignments and identify the subskills that their students have learned and those that they are struggling to master. As a team, they determine that many students can correctly identify a single structure in a text, such as problem-solution. However, students struggled to recognize that texts contain multiple structures used in conjunction to develop authors’ claims and ideas. Consequently, students’ analyses of relationships between the author’s claims and ideas and the text structures were often incomplete and inaccurate. After discussing possible action steps for Ms. Grant and Mr. Robinson, the team agrees that the Grade 9 ELA team should implement text structure instruction with authentic multistructure texts. Text Structure Instruction With Authentic Texts To prepare for and implement text structure instruction with authentic texts in general education classrooms, general and special education teachers should consider five steps. In the first step, teachers prepare for the lesson by developing objectives, creating and gathering instructional materials, and constructing and completing all instructional activities planned for their students (i.e., modeling, guided practice, independent practice). In the four subsequent steps, teachers deliver explicit instruction (Archer & Hughes, 2011). The onset of explicit instruction involves Purposeful preparation is crucial for teachers of students with or at risk for LD to properly implement text structure instruction with authentic texts. Before learning to identify and analyze the author’s use of multiple structural elements in an authentic text, students must be able to identify single text structures (Jones et al., 2016). This initial phase of text structure instruction is often implemented with controlled exemplar texts (e.g., Roehling et al., 2017). After mastering single structures, students are ready to apply their cumulative knowledge to a more authentic and complex text. Develop objectives. To prepare for instruction with texts containing multiple structures, teachers first develop the targeted learning objectives. Objectives are based on the standards to which instruction will be aligned. When reading comprehension instruction is being planned, the targeted standard is often broken down, or unpacked, into subskills that can be taught in individual lessons (Hughes, Morris, Therrien, & Benson, 2017). Teachers choose the subskills necessary for students to continue their progression to the grade-level reading standard and develop objectives that reflect these subskills. For example, text structure instruction may be aligned to CCSS.ELA-LITERACY. RI.9, which requires students to “analyze in detail how an author’s ideas or claims are developed and refined by particular sentences, paragraphs, or larger portions of a text (e.g., a section or chapter)” (NGACBP & CCSSO, 2010b, p. 2). To master this standard, students must develop a number of subskills. First, they have to be able to determine if an author is making claims or providing ideas (i.e., identify the author’s purpose). Second, students need to summarize the author’s claims or ideas. Third, students need to identify structural elements, particularly March/April 2020 “ Text mapping is a strategy that has been introducing the lesson to students. Then, teachers model the cognitive processes required to identify and analyze text structures. After modeling, teachers guide student practice in applying these processes before providing independent practice opportunities and evaluating student learning. 235 F i g u r e 2 Resources for selecting texts Tools for Quantitatively Analyzing Texts Description URL Lexile Analyzer: reports the Lexile® level of an entered text https://lexile.com/analyzer/ Readability Analyzer: reports the Gunning Fog, Flesch-Kincaid, SMOG, Dale-Chall, and Fry scores for an entered text https://datayze.com/readability-analyzer.php Readability Calculator: reports the Coleman Liau index, Flesh-Kincaid Grade Level, Automated Readability Index, and SMOG scores for entered text https://www.online-utility.org/english/readability_ test_and_improve.jsp Text Easability Assessor: reports the narrativity, syntactic simplicity, word concreteness, referential cohesion, and deep cohesion scores of entered text http://tea.cohmetrix.com/ Tools for Qualitatively Analyzing Texts Description URL Difficult and Extraneous Word Finder: identifies rare and long words in an entered text https://datayze.com/difficult-word-finder.php Qualitative Measures: crowdsourced reports of qualitatively analyzed books https://www.teachingbooks.net/support. cgi?f=support_howtouse&start#titlesearch Qualitative Measures Rubric: rubric displaying four levels of text complexity and descriptors for qualitative measures https://achievethecore.org/content/upload/ SCASS_Info_Text_Complexity_Qualitative_ Measures_Info_Rubric_2.8.pdf TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 52, No. 4 Sources of Informational Texts 236 Description URL Find a Book: searchable tool within the Lexile® Framework https://fab.lexile.com/ ReadWorks Reading Passages: fiction and nonfiction passages sorted by topic https://www.readworks.org/find-content#!q:/g:/t:/ pt:/features:/ Pros and Cons of Current Issues: articles outlining opposing arguments related to controversial issues https://www.procon.org/ Smithsonian Tween Tribune: news stories sorted by topic and available at a range of difficulty levels https://www.tweentribune.com/ those that develop the author’s claims or ideas. Finally, students must analyze how structural elements are organized to present the claims and ideas. Select reading materials. When authentic texts are being selected for students with or at risk for LD, there are several important considerations. The texts must be complex enough to engage students in rigorous reading instruction but still accessible enough for students to be successful with the assigned instructional task (Swanson & Wexler, 2017). In addition, teachers should consider whether the text will motivate and engage students by containing elements of cultural relevancy, offering different perspectives on issues, or making connections to real-world events (Leko, Mundy, Kang, & Datar, 2013). Although it may be tempting to use a readability level as the indicator of a text’s appropriateness, readability alone does not fully capture the complexity of a text (Reed & Kershaw-Herrera, 2016; Lupo, Tortorelli, Invernizzi, Ryoo, & Strong, 2019). Rather, teachers need to combine quantitative indicators of a text’s difficulty with qualitative indicators, such as the demands that the text places on students’ background knowledge, the density of the information presented, and the use of abstract or figurative language (Pearson & Hiebert, 2013). Resources for determining a text’s complexity and for locating authentic informational text are Create guides. Figure 1 contains a text structure guide that students can use as a reference while reading informational text and completing activities related to analyzing structural elements. In addition to defining each common type of structure and offering a sample map that might be used to visually represent information in the associated organizational pattern, the guide contains three other types of supports. First, it includes guiding questions that a teacher can use to shape students’ thinking about the information in a text and the functions of particular structural elements (Williams et al., 2016). The guiding questions in Figure 1 can be used with any text containing the specified structure, but teachers also may need to create other kinds of guiding questions that are specific to the content of an assigned text (Williams & Pao, 2011). The second type of support included in the text structure guide is the column containing sample signal words and phrases. Students can use these as indicators of certain text structures (Meyer, Wijekumar, & Lei, 2018). For example, students might learn to associate the word conversely with a difference, or contrast, within the compare-contrast text structure. Although this is helpful when still becoming familiar with how authors incorporate the organizational patterns, students are not taught that signal words alone are evidence of a particular type of structure, because many of these words can be used in a range of text structures (e.g., in addition, consequently; Hebert et al., 2016). The last support listed on the text structure guide is the list of structure partners. These are offered as examples of how two text structures might appear together in a paragraph or section because one organizational pattern is being used as support or elaboration for another structure. For example, a text written to present possible solutions to a problem may describe the causes that resulted in the problem, compare and contrast the different solutions offered, and outline the steps in the process of solving the problem. The author uses the partner text structures of description, cause-effect, compare-contrast, and sequencing to support the overarching structure of problem-solution. Students can use the structure partners to self-monitor their comprehension while reading and to organize important ideas and claims from a text (Meyer & Poon, 2001). Complete teacher versions. Thorough preparation for text structure instruction involves teachers constructing and completing all instructional activities planned for students. This includes •• Recording the author’s purpose statements •• Identifying structural elements (e.g., problem, effect) •• Annotating relationships between structural elements •• Creating a text map for each chosen text •• Scripting a think-aloud •• Crafting and answering written and oral questions Completing these portions in advance allows teachers to preview the thought processes needed by students to complete instructional tasks and anticipate student misunderstandings. Ms. Grant and Mr. Robinson decide to use texts that inform the reader about a controversial political issue: U.S. immigration policy. For the modeling portion of the lesson, they choose a short overview of the history of immigration policy in the United States. Both teachers reread the text several times, completing all steps of the text structure analysis on a teacher copy of the text. Ms. Grant will be conducting the think-aloud, so she crafts a bulleted script of the most important points to include and creates a teacher copy of the exemplar text map (see Figure 3). She shares these materials with Mr. Robinson and asks for his feedback. Next, Ms. Grant and Mr. Robinson complete the same steps with the texts that they select for guided and independent practice. They also develop guiding questions that will help students identify and analyze the text structures. For example, they may ask students, “In paragraph 3, what type of structure is the author using when he explains push-pull factors of immigration?” Throughout their preparation, they note any content or skills that may be difficult for students. For example, in a text that outlines differing viewpoints on immigration reform, Ms. Grant anticipates that students may struggle to recognize that the author is combining problem-solution and compare-contrast structures. Step 2: Introduce the Lesson Before teaching new content, teachers introduce the lesson to students. This step is crucial to ensuring that students understand the purpose of the lesson and make connections to previously learned strategies and content related to text structure instruction. Review relevant knowledge. When ready to begin the text structure lesson, teachers review the definition of text structure and how recognizing organizational patterns can support students’ comprehension of informational texts. Then, students briefly discuss any of the structure types learned in previous lessons. In addition, teachers review any strategies that students have learned for identifying and analyzing structural elements (e.g., text maps, guiding questions, signal words; Lovett et al., 1996). Discuss objectives. Teachers present the learning objectives to students and explain their importance, including contexts in which students will apply their learning (Riccomini, Morano, & Hughes, 2017). Importantly, teachers also preview the strategy that students will use to achieve the objective, and they explain how the strategy will benefit students’ learning (Archer & Hughes, 2011). At the beginning of the lesson, Ms. Grant displays and reads the following learning objective to her students: “Students will be able to identify text structures and analyze their relationships to the author’s claims or ideas.” She describes the importance of the objective and how students might apply their learning. She says, “Identifying and analyzing text structures will help you monitor your reading comprehension of informational texts. This is a skill that will help you succeed in all subjects, such as science and social studies.” Next, Ms. Grant previews the strategy that March/April 2020 provided in Figure 2. Depending on the length of the chosen texts, several may be necessary to complete an explicit instructional sequence of modeling, guided practice, and independent practice. Because the text structure may change multiple times within and across paragraphs of authentic material (Meyer, 2003), it is important to spend time identifying the structural elements in each text selected for instruction. 237 TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 52, No. 4 F i g u r e 3 Text structure map example: Causes and effects of the U.S. immigration policy 238 students will use to achieve the learning objective. She displays the text map through a document camera and overhead projector and identifies its components. To wrap up the lesson introduction, Ms. Grant explains why she decided to use the text map to analyze the relationships between text structures and the author’s claims or ideas. “A text map is a good strategy to use when analyzing structural elements in multistructure texts. This way, readers can display how texts and their ideas and claims are organized, which helps to visualize how these structural elements fit together. This helps readers check whether or not the analysis makes sense, which means that they can monitor how well they are understanding the text. There are other strategies that readers use to analyze structural elements. For example, a note frame can be used to record information about text structures. However, this is not the best strategy for analyzing multistructure texts, because it does not help readers visualize how the structural elements fit together.” Step 3: Model The purpose of the modeling portion of the lesson is for students to learn the cognitive processes for identifying and analyzing structural elements (Williams et al., 2016). Teachers’ thinking is revealed through a think-aloud, in which teachers narrate their thoughts and display how they make annotations, responses, or other markings in the text relevant to the structure strategies. Before beginning the think-aloud, teachers read the text aloud once to students, discuss any unknown vocabulary words and textual features (e.g., charts, graphs, images), and have students state the main idea of the text (cf. Stevens, Park, & Vaughn, 2018). Then, teachers review two common types of purposes for informational texts (persuade, inform). Finally, teachers briefly narrate how to determine the author’s purpose and combine the author’s purpose and the main idea to write an author’s purpose statement. Identifying the main idea and determining the author’s purpose are essential steps to analyzing the structure of an authentic text (Meyer & Poon, 2001; Wijekumar, Meyer, & Lei, 2017). The reason is that the reader needs to understand whether the author is trying to communicate claims or ideas before analyzing how the author organizes the text with certain structures (Meyer, 2003). For example, during the first reading of the immigration overview passage, Ms. Grant completes the following steps to model how to create an author’s purpose statement: document camera and projector. As she reads, she pauses to discuss several unfamiliar terms that are crucial to understanding the text: “asylum” and “nativist.” She also reviews a chart that depicts the rise in immigration to the United States during the midnineteenth century. Ms. Grant identifies the main idea of the passage: “There are many factors that have affected U.S. immigration policy.” Next, Ms. Grant identifies the purpose of the text. She needs to determine if the author is making a claim or providing ideas. If the author is making a claim, the purpose is to persuade the reader. If the author is providing ideas, the purpose is to inform the reader. She says, “At first, I thought that the author was making a claim about immigration and that the purpose of the text may be to persuade the reader about immigration. This is a very controversial issue, so I could think that the author has an opinion and is trying to make the audience have that same opinion. However, when we read the text, I see that the author was just presenting information to the reader. Therefore, I think the purpose is to inform the reader. I will combine the purpose and the main idea to write my author’s purpose statement at the top of my text map: The author’s purpose is to inform the reader that many factors have affected U.S. immigration policy.” In a small group lesson within the general education classroom, Ms. Grant reads and displays the passage to students through a Next, teachers model and explain the purpose for the second reading of the text (Fisher & Frey, 2014). They explain to On her copy of the text, Ms. Grant points to a sentence in the first paragraph of the passage. “In paragraph 1, we read that many Chinese and Irish immigrants came to America to work, which led to racial tensions between Chinese and American workers and religious tensions between Irish-Catholic and AmericanProtestant workers. I ask myself, ‘Why is the author including this information? Is this information important to helping the author inform the reader about factors that have affected immigration policy?’ I think it is important because the next sentence says that racial and religious tensions influenced lawmakers to restrict immigration based on religion and nationality. That definitely means that these tensions affected immigration policy, which I identified as the main idea of the passage. Next, I will take a look at my text structure guide to support my thinking about how to identify structural elements in this section. I can see that the first sentence uses the phrase ‘led to,’ which is a signal phrase that sometimes indicates cause-effect structure. But if that is true, what is the cause, and what is the effect? I think that in these sentences, the influx of Chinese immigrants caused, or resulted in, racial tension.” Ms. Grant underlines and labels the pertinent phrases “cause” and “effect.” Then, she draws an arrow from the cause to the effect. “However, I think that the author is also beginning to use another text structure here. When we read the text the first time, I remember that the author was listing events that have happened in U.S. history. The influx of Chinese and Irish immigrants was the first event in the text. I can see on my text structure guide, under ‘Structure Partners,’ that authors sometimes tell the reader about the results, or effects, of certain events. I think that is exactly what the author is doing in these two sentences! The reader learns about an event in U.S. history that led to influential racial and religious tensions.” Finally, teachers model creating a text map of structural elements (see exemplar in Figure 3) to display the organization of important information that was annotated in the text (Boon et al., 2015). Text maps may be created with paper and pencil or a computer program (e.g., presentation slides or concept-mapping software). Step 4: Guided Practice With Identifying and Analyzing Text Structures Following the think-aloud, students are provided multiple opportunities to practice applying the learned strategies (Coiro, 2011). Teacher-formed pairs or small groups of students work together to read aloud a new short passage. To scaffold this gradual release of responsibility to students with or at risk for LD, teachers may highlight or underline sections, paragraphs, or sentences in the text that are crucial to communicating the author’s claims or ideas (Lovett et al., 1996). For students experiencing particular difficulty, teachers might also provide a guide for determining the author’s purpose. After the first reading of the text, students use the text structure guide as they reread and collaborate to identify the structural element included in each highlighted section. Teachers continuously circulate to monitor student work and probe their thinking (Hughes et al., 2017). For example, teachers might ask, “What were the clues in the text that helped you identify the text structure type?” Next, the pairs or small groups collaboratively respond to guiding questions about the relationships between structural elements (e.g., How does the author’s description of the earthquake in El Salvador relate to the statement that the U.S. government granted Salvadorans temporary protected status?). If necessary, teachers might further scaffold the guiding questions by offering them in a multiplechoice format (Meyer et al., 2010). Again, teachers circulate to redirect misunderstandings and probe students’ analyses of the structural elements. After students have completed the guiding questions, they work together to create a text map. It is important that the text map visually represent the relationships among textual information (Roehling et al., 2017). Depending on students’ experience with text structure mapping, students can finish filling in blanks on a partially completed map, complete a blank version of the teachercreated text structure map, or choose for themselves the type of map that is appropriate for the structure and record the requisite information (Meyer et al., 2010). As students work, teachers question students about how their maps represent the author’s organization of the text’s structure, including how recorded information is related or might be labeled a structural element (Meyer & Poon, 2001). When students have demonstrated that they can identify and analyze predetermined structural elements using guiding questions and text maps, the teacher begins to remove instructional scaffolding and releases additional responsibility to students (Fisher, Frey, & Lapp, 2011). In the next portion of guided practice, pairs or small groups of students collaborate to read a new short text, write an author’s purpose statement, annotate the text to identify structural elements, and create a text structure map. As they work, students may still use instructional supports, such as the text structure guide. However, students are now responsible for identifying important sentences, sections, or paragraphs in the text and are not supported by guiding questions in doing so. Yet, teachers are still checking students’ understanding of text structure and redirecting any misunderstandings that may arise. Throughout guided practice, teachers also conduct targeted re-teaching (e.g., additional modeling, guided discussions) on specific skills or concepts with which the students have difficulty (Hughes et al., 2017). Importantly, students may require practice with multiple authentic texts before independently practicing the text structure strategies. March/April 2020 students that the purpose of the second reading is to identify and analyze structural elements used to achieve the author’s purpose and develop the author’s claims or ideas. In a think-aloud format, teachers annotate the text, labeling structural elements by underlining them and writing the name of each element (e.g., problem, cause) in the margins. After identifying each element, teachers explain its importance and how it helps the author develop the claims or ideas. Furthermore, they discuss the effect of the structural element on the reader; in particular, they emphasize how the element helps achieve the author’s purpose. Teachers also model how to illustrate relationships between elements by connecting them with arrows. Throughout the think-aloud, teachers refer to the text structure guide (see Figure 1). For example, Ms. Grant begins her think-aloud in the following way: 239 F i g u r e 4 Text structure map rubric TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 52, No. 4 Step 5: Provide Independent Practice and Evaluate Student Learning 240 Once students have demonstrated that they are ready to apply the text structure strategies independently, teachers assign a new informational text. Students and teachers follow the same procedures used in guided practice for identifying and analyzing text structure. Students are able to work without peer support at this stage, but they still require instructional feedback (Hughes et al., 2017). One means of providing this is through a text structure map rubric (see Figure 4). Students receive a numerical score on the rubric, as well as specific comments from teachers that outline strengths and weaknesses of the text structure analysis represented in the text map (Meyer et al., 2010). Students can use this feedback to revise their text maps before resubmitting them for further evaluation. Through these written tasks, students refine their knowledge and application of text structure and related strategies (Williams & Pao, 2011). Concluding Thoughts For students with or at risk for LD to improve their reading comprehension of informational texts, teachers must implement explicit scaffolded text structure instruction (Meyer & Ray, 2011) and provide students opportunities to apply learned strategies to new texts (Hebert et al., 2016). General and special educators, such as Mr. Robinson and Ms. Grant, can use authentic texts and gradually increase the relative complexity of tasks to ensure that their students experience robust grade-level text structure instruction that can improve their ability to use informational texts to learn content (Pyle et al., 2017). Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Leah M. Zimmermann, M.Ed., and Deborah K. Reed, Ph.D., Iowa Reading Research Center, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA. Address correspondence concerning this article to Leah M. Zimmermann, M.Ed., Iowa Reading Research Center, University of Iowa, 103 Lindquist Center, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA (e-mail: leah-zimmermann@uiowa.edu). ORCID iDs Leah M. Zimmermann https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0594-9114 Deborah K. Reed https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0874-1412 References Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Effective and efficient teaching. New York City, NY: Guilford Press. Boardman, A. G., Klingner, J. K., Buckley, P., Annamma, S., & Lasser, C. J. (2015). The efficacy of collaborative strategic reading in middle school science and social studies classes. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 28, 1257–1283. doi:10.1007/s11145-015-9570-3 Boon, R. T., Paal, M., Hintz, A.-M., & CorneliusFreyre, M. (2015). A review of story mapping instruction for secondary students with LD. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 13, 117–140. Coiro, J. (2011). Talking about reading as thinking: Modeling the hidden complexities of online reading comprehension. Theory Into Practice, 50, 107–115. doi:10.1080/00405841.2011.558435 Denton, C. A., Enos, M., York, M. J., Francis, D. J., Barnes, M. A., Kulesz, P. A., . . . Carter, S. (2015). Text-processing differences in adolescent adequate and poor comprehenders reading accessible and challenging narrative and informational text. Reading Research Quarterly, 50, 393–416. doi:10.1002/rrq.105 Duke, N. K., Purcell-Gates, V., Hall, L. A., & Tower, C. (2006). Authentic literacy activities for developing comprehension and writing. Reading Teacher, 60, 344–355. doi:10.1598/ rt.60.4.4 Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2014). Close reading as an intervention for struggling middle school readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57, 367–376. doi:10.1002/jaal.266 Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Lapp, D. (2011). Coaching middle-level teachers to think aloud improves comprehension instruction and student reading achievement. The Teacher Educator, 46, 231–243. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2011.580043 Gajria, M., Jitendra, A. K., Sood, S., & Sacks, G. (2007). Improving comprehension of expository text in students with LD: A research synthesis. Journal of Learning Meyer, B. J. F., & Poon, L. W. (2001). Effects of structure strategy training and signaling on recall of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 141–159. doi:10.1037/00220663.93.1.141. Meyer, B. J. F., Wijekumar, K., & Lei, P. (2018). Comparative signaling generated for expository texts by 4th–8th graders: Variations by text structure strategy instruction, comprehension skill, and signal word. Reading and Writing, 31, 1937–1968. doi:10.1007/s11145-018-9871-4 Meyer, B. J. F., Wijekumar, K., Middlemiss, W., Higley, K., Lei, P.-W., Meier, C., & Spielvogel, J. (2010). Web-based tutoring of the structure strategy with or without elaborated feedback or choice for fifth- and seventhgrade readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 45, 62–92. doi:10.1598/RRQ.45.1.4 National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010a). English language arts standards—Introduction: Key design consideration. Retrieved from http:// www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/ introduction/key-design-consideration/ National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010b). English language arts standards—Reading: Informational text— Grades 9–10. Retrieved from http://www .corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/RI/9-10/ National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010c). English language arts standards—Standard 10: Range, quality, and complexity—Range of text types for 6–12. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards. org/ELA-Literacy/standard-10-range-qualitycomplexity/range-of-text-types-for-612/ O’Connor, R. E., Beach, K. D., Sanchez, V., Bocian, K. M., Roberts, S., & Chan, O. (2017). Building better bridges: Teaching adolescents who are poor readers in eighth grade to comprehend history text. Learning Disability Quarterly, 40, 174–186. doi:10.1177/0731948717698537 Pearson, P. D., & Hiebert, E. H. (2013). The state of the field: Qualitative analyses of text complexity (Reading Research Report 13.01). Santa Cruz, CA: TextProject. Pyle, N., Vasquez, A. C., Lignugaris/Kraft, B., Gillam, S. L., Reutzel, D. R., Olszewski, A., & Pyle, D. (2017). Effects of expository text structure interventions on comprehension: A meta-analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 52, 469–501. doi:10.1002/rrq.179 Reed, D. K., Petscher, Y., & Truckenmiller, A. J. (2017). The contribution of general reading ability to science achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 52, 253–266. doi: 10.1007/s11145-015-9619-3 Reed, D. K., & Kershaw-Herrera, S. (2016). An examination of text complexity as characterized by readability and cohesion. Journal of Experimental Education, 84, 75-97. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2014.963214 Riccomini, P. J., Morano, S., & Hughes, C. A. (2017). Big ideas in special education: Specially designed instruction, high-leverage practices, explicit instruction, and intensive instruction. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50, 20–27. doi:10.1177/0040059917724412 Roehling, J. V., Hebert, M., Nelson, J. R., & Bohaty, J. J. (2017). Text structure strategies for improving expository reading comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 71, 71–82. doi:10.1002/trtr.1590 Stevens, E. A., Park, S., & Vaughn, S. (2018). A review of summarizing and main idea interventions for struggling readers in Grades 3 through 12: 1978–2016. Remedial and Special Education, 40, 131–140. doi:10.1177/0741932517749940 Swanson, E., & Wexler, J. (2017). Selecting appropriate text for adolescents with disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 49, 160–167. doi:10.1177/0040059916670630 Wijekumar, K., Meyer, B. J. F., & Lei, P. (2017). Web-based text structure strategy instruction improves seventh graders’ content area reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109, 741–760. doi:10.1037/edu0000168 Williams, J. P., Kao, J. C., Pao, L. S., Ordynans, J. G., Atkins, J. G., Cheng, R., & DeBonis, D. (2016). Close analysis of texts with structure (CATS): An intervention to teach reading comprehension to at-risk second graders. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 1061–1077. doi:10.1037/edu0000117 Williams, J. P., & Pao, L. S. (2011). Teaching narrative and expository text structure to improve comprehension. In R. E. O’Connor & P. F. Vadasy (Eds.), Handbook of reading interventions (pp. 254–278). New York, NY: Guilford Press. TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 232–241. Copyright 2020 The Author(s). March/April 2020 Disabilities, 40, 210–225. doi:10.1177/00222194 070400030301 Hebert, M., Bohaty, J. J., Nelson, J. R., & Brown, J. (2016). The effects of text structure instruction on expository reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 609–629. doi:10.1037/edu0000082 Hock, M. F., Brasseur-Hock, I. F., Hock, A. J., & Duvel, B. (2017). The effects of a comprehensive reading program on reading outcomes for middle school students with disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51, 195–212. doi:10.1177/0022219415618495 Hughes, C. A., Morris, J. R., Therrien, W. J., & Benson, S. K. (2017). Explicit instruction: Historical and contemporary contexts. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 32, 140–148. doi:10.1111/ldrp.12142 Jones, C. D., Clark, S. K., & Reutzel, D. R. (2016). Teaching text structure: Examining the affordances of children’s informational texts. The Elementary School Journal, 117, 143–169. doi:10.1086/687812 Joseph, L. M., & Eveleigh, E. L. (2011). A review of the effects of self-monitoring on reading performance of students with disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 45, 43–53. doi:10.1177/0022466909349145 Leko, M. M., Mundy, C. A., Kang, H.-J., & Datar, S. D. (2013). If the book fits: Selecting appropriate texts for adolescents with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 48, 267–275. doi:10.1177/1053451212472232 Lovett, M. W., Borden, S. L., Warren-Chaplin, P. M., Lacerenza, L., DeLuca, T., & Giovinazzo, R. (1996). Text comprehension training for disabled readers: An evaluation of reciprocal teaching and text analysis training programs. Brain and Language, 54, 447–480. doi:10.1006/brln.1996.0085 Lupo, S. M., Tortorelli, L., Invernizzi, M., Ryoo, J. H., & Strong, J. Z. (2019). An exploration of text difficulty and knowledge support on adolescents’ comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly. Advance online publication. doi:10.1002/rrq.247 Meyer, B., & Ray, J. F. (2011). Structure strategy interventions: Increasing reading comprehension of expository text. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 4, 127–152. Meyer, B. J. F. (2003). Text coherence and readability. Topics in Language Disorders, 23, 204–224. doi:10.1097/00011363-20030700000007 241 Copyright of Teaching Exceptional Children is the property of Sage Publications Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.