external match loads imposed upon ultimate frisbee players - a comparison between playing positions

advertisement

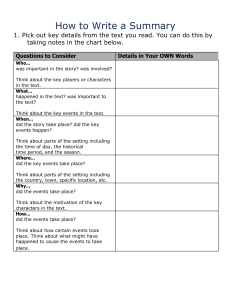

+Model ARTICLE IN PRESS SCISPO-3442; No. of Pages 3 Science & Sports (2020) xxx, xxx—xxx Disponible en ligne sur ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com LETTER TO THE EDITOR External match loads imposed upon Ultimate Frisbee players: A comparison between playing positions Charges de match externes imposées aux joueurs de Ultimate Frisbee : comparaison entre les positions de jeu 1. Introduction Ultimate Frisbee (UF) is a non-contact team sport where the main team objective is to score goals by catching a plastic disc in the attacking end-zone [1]. Matches can be time-bound (2 × 30-min halves) or score-bound (first team to score 15 points is declared the winner) [2]. It has been shown that UF players cover a total distance of 4700 ± 470 m, with 3490 ± 350 m covered performing low-intensity running (0—13.9 km·h−1 ), 630 ± 140 m performing high-intensity running (14—22 km·h−1 ), and 210 ± 110 m sprinting (> 22 km·h−1 ) during matches [3]. Players are divided into different playing positions (i.e., cutters and handlers) due to their role during the match. In this sense, while cutters mainly conquer the end zone of the opposing team, handlers facilitate movement of the disc across the pitch, potentially creating pronounced differences in the movements and subsequent physical demands encountered according to position. However, no previous research has quantified the external loads (e.g., distance covered at different absolute speed ranges or short-term, high-intensity actions such as accelerations and decelerations) completed by players during UF matches relative to playing position. Consequently, this team-based case study aimed to quantify and compare the external loads experienced by cutters and handlers during UF matches. 2. Methods Twelve national-level UF players competing in an elite mixed-sex competition participated in the study. Players were divided according to playing position (7 cutters and 5 handlers). All players participated voluntarily and procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013), approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Isabel I. The official matches consisted of 2 × 30-min halves with a 5-min rest period between halves. However, when full-time was reached, play continued until a team scored as per standard rules in UF [3]. The average duration of matches was 62.3 ± 13.8 min, during which the players were active for 34.9 ± 11.4 min, and the remaining 27.4 ± 10.2 min was accounted for by breaks (no activity) between points, referee discussions, and substitutions. The playing pitch consisted of an outdoor, natural, grass surface, spanning 100 m (including 2 × 15-m end zones) in length × 60 m in width. An official referee tabulated the score and ensured rules were followed during matches. External load was monitored for each player in all matches using microsensor units containing a 10-Hz global positioning system (WIMU PROTM , RealTrack Systems, Almería, Spain) [4]. Microsensor units were harnessed in a tight-fitting vest worn by the players throughout matches. The microsensor units were activated 15 min before the start of each match, in accordance with manufacturer recommendations. Data were downloaded post-match to a computer and analysed using a customised software package (WIMU SPRO, Almería, Spain). The total distance covered was taken as a key outcome measure with further distance measures derived for different locomotive categories according to movement speed: low-intensity walking (< 3.9 km·h−1 ), walking (4.0—7.9 km·h−1 ), jogging (8.0—13.9 km·h−1 ), highintensity running (>14.0 km·h−1 ), and high-speed running (>22.0 km·h−1 ). Also, distance covered while accelerating and decelerating was also determined for different intensity categories: low-intensity acceleration (LACC; 1.0 to 2.5 m·s−2 ), medium-intensity acceleration (MACC; 2.5 to 4.0 m·s−2 ), high-intensity acceleration (HACC; > 4.0 m·s−2 ), low-intensity deceleration (LDEC; −1.0 to −2.5 m·s−2 ), medium-intensity deceleration (MDEC; −2.5 to −4.0 m·s−2 ), and high-intensity deceleration (HDEC; < −4.0 m·s−2 ). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Effect sizes (ES) with uncertainty of the estimates shown as 90% confidence limits (CL) were used to quantify the magnitude of the difference between playing positions. ES were classified as trivial (< 0.2), small (0.2—0.6), moderate (0.6—1.2), large (1.2—2.0), very large (2.0—4.0) and extremely large (> 4.0) [5]. Inference was classified as https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2020.02.014 0765-1597/© 2020 Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved. Please cite this article in press as: Raya-González J, et al. External match loads imposed upon Ultimate Frisbee players: A comparison between playing positions. Sci sports (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2020.02.014 +Model SCISPO-3442; No. of Pages 3 ARTICLE IN PRESS 2 Letter to the editor Table 1 The external loads (mean ± SD) encountered during official Ultimate Frisbee matches according to playing position with mean differences. Variables All (n = 38) Cutters (n = 21) Handlers (n = 17) Mean difference; ±90% CL Total distance (m) Low-intensity walking (m) Walking (m) Jogging (m) High-intensity running (m) High-speed running (m) LACC (m) MACC (m) HACC (m) LDEC (m) MDEC (m) HDEC (m) 3955 ± 1000 938 ± 236 1164 ± 356 1113 ± 412 741 ± 280 77 ± 84 690 ± 224 438 ± 177 91 ± 164 483 ± 164 198 ± 82 63 ± 41 3965 ± 1127 883 ± 230 1089 ± 374 1191 ± 436 802 ± 334 80 ± 89 696 ± 251 461 ± 208 116 ± 100 504 ± 174 213 ± 99 74 ± 43 3942 ± 851 1004 ± 232 1256 ± 319 1016 ± 370 666 ± 174 74 ± 79 682 ± 193 408 ± 130 59 ± 36 456 ± 150 181 ± 54 49 ± 34 1.4; ± 15.0 14.8; ± 16.4 19.4; ± 21.4 −14.9; ± 18.7 −11.1; ± 17.7 −17.2; ± 82.1 0.3; ± 19.1 −4.8; ± 22.4 −8.8; ± 65.4 −9.3; ± 18.5 −6.1; ± 25.2 −29.9; ± 28.1 n: number of observations overall and for playing position; CL: confident limits; SD: standard deviation; LACC: low-intensity acceleration between 1 and 2.5 m·s−2 ; MACC: medium-intensity acceleration between 2.5 and 4 m·s−2 ; HACC: high-intensity acceleration above 4 m·s−2 ; LDEC: low-intensity deceleration between −2.5 and −1 m·s−2 ; MDEC: medium-intensity deceleration between −4 and −2.5 m·s−2 ; HDEC: high-intensity deceleration less than −4 m·s−2 . Figure 1 Differences between cutters and handlers in the distances covered at different locomotive intensities (1A) and acceleration and deceleration intensities (1B) during official Ultimate Frisbee matches. LACC: low-intensity acceleration between 1 and 2.5 m·s−2 ; MACC: medium-intensity acceleration between 2.5 and 4 m·s−2 ; HACC: high-intensity acceleration above 4 m·s−2 ; LDEC: low-intensity deceleration between −2.5 and −1 m·s−2 ; MDEC: medium-intensity deceleration between −4 and −2.5 m·s−2 ; HDEC: high-intensity deceleration less than −4 m·s−2 . unclear if the 90% CL overlapped the thresholds for the smallest worthwhile positive and negative effects [5]. The mean differences, CL and ES were calculated using a customised spreadsheet Microsoft Excel® (v15.0; Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA, USA). 3. Results The external loads imposed upon all players as well as according to playing position during matches are presented in Table 1. Handlers covered more (small) distance performing low-intensity walking and walking than cutters, while cutters travelled higher (small) distances undertaking highintensity running than handlers (Fig. 1A). Likewise, cutters completed greater (small) distances completing HACC and HDEC than handlers (Fig. 1B). 4. Conclusions This is the first study to quantify the external match loads imposed upon UF players competing at an elite level, as well as the first to explore match demands relative to playing position. The main results of this exploratory team-based case study demonstrate playing position influences the external loads experienced during mixed-sex UF matches. Specifically, handlers appear to completed greater recovery opportunities than cutters as evidenced by higher volumes of walking during matches. Conversely, cutters experienced greater running demands, with a heavier reliance on intense accelerations and decelerations than handlers during matches. These findings are not surprising given cutters are key players in scoring points since they must conquer the end zone of the opposing team. More precisely, cutters usually execute high-intensity efforts to Please cite this article in press as: Raya-González J, et al. External match loads imposed upon Ultimate Frisbee players: A comparison between playing positions. Sci sports (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2020.02.014 +Model SCISPO-3442; No. of Pages 3 ARTICLE IN PRESS Letter to the editor create space between opposing players when on offence for passing opportunities from handlers, who primarily facilitate movement of the disc across the pitch. These results indicate coaching and performance staff of elite UF teams should closely consider the specific demands of each playing position when developing training programmes and recovery strategies to optimally prepare players for competition. Disclosure of interest The authors declare that they have no competing interest. Acknowledgements The authors are gratefully for the involvement of the Cidbee Ultimate Frisbee Club in this study. Also, we thank all the UF players who volunteered to participate in the study. This study was supported by the University Isabel under agreement UI1-PI001. 3 [3] Krustrup P, Mohr M. Physical demands in competitive Ultimate Frisbee. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29(12):3386—91. [4] Bastida Castillo A, Gómez Carmona CD, De la Cruz Sánchez E, Pino Ortega J. Accuracy, intra- and inter-unit reliability, and comparison between GPS and UWB-based position-tracking systems used for time-motion analyses in soccer. Eur J Sport Sci 2018;18(4):450—7. [5] Hopkins WG, Marshall SW, Batterham AM, Hanin J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med Sci Sports Exer 2009;41(1):3—12. J. Raya-González a D. Castillo a,∗ A. Rodríguez-Fernández a A.T. Scanlan b a Faculty of Health Sciences, University Isabel I, Burgos, Spain b Human Exercise and Training Laboratory, School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, Australia ∗ References [1] Madueno MC, Kean CO, Scanlan AT. The sex-specific internal and external demands imposed on players during Ultimate Frisbee game-play. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2017;57(11):1407—14. [2] WFDF. Rules of Ultimate 2017, 2017. USA 2016:1—16 [Available from: http://www.wfdf.org/sports/rules-of-play/cat view /26-rules-of-play/32-ultimate/149-ultimate-rules-2013-2016]. Corresponding author. E-mail address: danicasti5@gmail.com (D. Castillo) Received 8 February 2019 Accepted 7 February 2020 Please cite this article in press as: Raya-González J, et al. External match loads imposed upon Ultimate Frisbee players: A comparison between playing positions. Sci sports (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2020.02.014