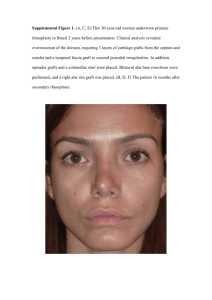

COSMETIC Revision Rhinoplasty after Open Rhinoplasty: Lessons from 252 Cases and Analysis of Risk Factors AQ1 AQ2 Serhat Sibar, M.D. Kemal Findikcioglu, M.D. Burak Pasinlioglu, M.D. Ankara, Turkey Background: In this study, patients who required aesthetic revision surgery after open rhinoplasty were retrospectively screened for risk factors. Methods: Two hundred fifty-two patients who underwent revision were included in the study. Nasal deformities before the revision were determined for each patient and evaluated in terms of their statistical relationship with preoperative nasal morphology and surgical techniques used. Results: The revision rate was found to be 10.8 percent. The three most common aesthetic reasons for revision were insufficient nasal tip rotation (37.7 percent), hanging columella (30.2 percent), and supratip deformity (28.6 percent). According to logistic regression analysis, the use of a strut increased the risk of inadequate nasal tip rotation by 5.3-fold compared to the tonguein-groove technique, whereas inadequate nasal tip projection before surgery increased this risk by 2-fold. Being older than 40 years increased the risk of hanging columella by 6.8-fold, whereas the use of strut grafting instead of the tongue-in-groove technique increased this risk by 5.9-fold. The use of strut grafts instead of the tongue-in-groove technique increased the risk of supratip deformity by 2.2-fold. Conclusions: To ensure adequate nasal tip rotation after surgery in patients with advanced age and low nasal tip projection and rotation, it will be more appropriate to either use the tongue-in-groove technique or rotate the nasal tip more than normal. In patients with advanced age (>40 years) and low nasolabial angle before surgery, the use of tongue-in-groove technique instead of strut grafting may be advantageous for reducing the incidence of supratip and hanging columella. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 148: 747, 2021.) CLINICAL QUESTION/LEVEL OF EVIDENCE: Risk, III. R hinoplasty is a discipline with a lifelong learning curve, and it is difficult to achieve predictable results in the long term. In the postoperative period, numerous changes in nasal morphology may occur because of time, along with many variables.1 These changes may necessitate revision surgery if they do not match the outcome predicted by the surgeon or the patient’s postoperative expectations. In the literature, revision rates of rhinoplasty vary between 5 and 15 percent.2–10 Rhinoplasty operations were performed using the open technique in our clinic, From the Department of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgery, Gazi University Hospital. Received for publication January 23, 2020; accepted March 15, 2021. Presented at the 41st Congress of the Turkish Society of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, in Samsun, Turkey, October 26 through 30, 2019, and awarded first place in the scientific competition of specialists, clinical studies. Copyright © 2021 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000008318 and the patients who needed revision surgery for aesthetic reasons were evaluated retrospectively for various risk factors. With the results obtained, we aimed to determine the factors that increase risk in terms of revision, and to find solutions to minimize revision rates. PATIENTS AND METHODS Patients who underwent open rhinoplasty performed by five different surgeons in our clinic between 2013 and 2018 were screened retrospectively. Overall, 478 of 4003 patients were excluded because of previously undergoing rhinoplasty at another center (secondary cases), use of the closed technique, having cleft lip or cleft palate, or having a history of maxillofacial trauma requiring Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. No funding was received for this article. www.PRSJournal.com AQ3 747 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery • October 2021 F1 surgery. Of the remaining 3525 patients, 2991 patients had at least 1-year follow-up and were screened for revision rhinoplasty. Revision rhinoplasty was performed in 324 patients, and 72 patients were excluded from the study because of lack of surgical notes or photographic documentation. The remaining 252 patients (after at least 1 year of follow-up) were included in the study for the analysis of possible risk factors before revision because of aesthetic concerns (Fig. 1). In addition to the demographic characteristics of the patients, parameters such as skin thickness, presence of external deviation and dorsal aesthetic lines, status of the bone and cartilage roof, nasal tip morphology, nasolabial angle, dorsal hump size, and nasal tip projection and rotation were evaluated based on preoperative photographs. Photographs were captured using a Canon EOS 60D (Canon, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) 18-135 IS lens with a fixed distance of 2 m between the camera and the patient in the photography room inside the clinic. Adobe Photoshop Version CC 2018 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, Calif.) was used for photographic analysis. The technical details of the operation were classified according to the patients based on the surgical notes and the personal archives of the surgeons. The existing deformities in the nose before the revision were determined for each patient through the photographs of the patients and evaluated in terms of the statistical relationship between nose morphology before the first operation and the techniques used during the operation. Statistical Analysis Data analysis was performed using SPSS Version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.). Normality of continuous variables was determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (range), whereas number and percentages were used for categorical data. Differences between groups in continuous and sequential data were compared using the MannWhitney U test. When comparing categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test was used in cases where one or more of the cells in a 2 × 2 probability table had an expected frequency of less than or equal Fig. 1. Study population and sample. 748 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Volume 148, Number 4 • Risk Factors for Revision Rhinoplasty to 5, and Pearson chi-square test was used in cases where one or more of the cells had an expected frequency of greater than 5. Determination of the best predictor(s) (hanging columella, supratip deformity, and insufficient nasal tip rotation) affecting certain deformities was assessed by multiple logistic regression analyses after adjustment for all possible confounding factors. Variables with a univariate test result of p < 0.20 were considered candidates for the multivariate model together with all variables of known clinical significance. Odds ratio and 95 percent confidence interval were calculated for each independent variable. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. RESULTS T1 T2 The revision rate was 10.8 percent, and no statistically significant difference was found between surgeons in terms of their revision rates (especially for the three most common complications). When the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were examined, the mean age was 31.9 years (range, 18 to 56 years). When the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were examined, the mean age was 31.9 years (range, 18 to 56 years) 30 (11.9 percent) patients were male, and 222 patients (88.1 percent) were female. For skin thickness analysis, the classification system previously described in the literature by Daniel was used (thick skin, N + 1, N + 2, N + 3; thin skin, N − 1, N − 2, N − 3; N, normal).11 Because of the low number of patients with thin skin [n = 17 (6.7 percent)], they were included in the same group comprising patients with normal skin thickness during statistical evaluation. Because the Turkish population has characteristics similar to the Middle Eastern population, the majority of patients who underwent revision surgery [n = 209 (82.9 percent)] had thick skin. A total of 62 patients (24.6 percent) had a history of previous nasal trauma, and 92 patients (36.5 percent) had preoperative external deviation; 179 patients (71 percent) had irregular dorsal aesthetic lines, 146 patients (57.9 percent) had a wide bone roof, 159 patients (63.1 percent) had a wide cartilage roof, and 163 patients (64.7 percent) had broad tip morphology (Table 1). The three most common nasal tip features in preoperative morphologic analysis were nasal tip asymmetry [n = 73 (29 percent)], tip fullness [n = 52 (20.6 percent)], and droopy tip [n = 40 (15.9 percent)], respectively (Table 2). Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients Characteristic No. of patients Age, yr Mean ± SD Range Age groups <30 yr 30–40 yr >40 yr Sex Male Female Skin thickness Normal or thin Thick Previous nasal trauma Preoperative external deviation Dorsal aesthetic lines Regular Irregular Bone roof Wide Normal Cartilage roof Narrow Wide Normal Tip Narrow Broad Normal Value (%) 252 31.96 ± 8.98 18–56 123 (48.8) 88 (34.9) 41 (16.3) 30 (11.9) 222 (88.1) 43 (17.1) 209 (82.9) 62 (24.6) 92 (36.5) 73 (29.0) 179 (71.0) 146 (57.9) 106 (42.1) 63 (25.0) 159 (63.1) 30 (11.9) 13 (5.2) 163 (64.7) 76 (30.2) The mean preoperative nasolabial angle was 91.2 degrees (range, 73 to 110 degrees). The mean size of dorsal hump was 4.04 mm (range, 1 to 9 mm). Insufficient nasal tip rotation was detected in 172 patients (68.3 percent). For nasal ridge reconstruction, spreader flap technique Table 2. Frequency Distribution of Patients in Terms of Preoperative Nasal Tip Morphology Characteristic No. (%) No. of patients Normal Asymmetric Bulbous Alar flare Hanging columella Footplate flare Tip fullness Unitip Droopy tip ANS hypertrophy Bifidity Nostril asymmetry Cephalic orientation Alar retraction Lateral crural concavity Intercrural groove Short medial crus Long medial crus Broad tip Other 252 13 (5.2) 73 (29.0) 30 (11.9) 24 (9.5) 35 (13.9) 22 (8.7) 52 (20.6) 12 (4.8) 40 (15.9) 9 (3.6) 13 (5.2) 7 (2.8) 7 (2.8) 6 (2.4) 10 (4.0) 4 (1.6) 4 (1.6) 7 (2.8) 2 (0.8) 6 (2.4) ANS, anterior nasal spine. 749 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. AQ4 Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery • October 2021 T3 F2, F3, T4 was preferred in 116 patients (65.9 percent), and spreader grafts were preferred in 86 patients (34.1 percent). For nasal tip support, strut grafting was used in 184 patients (73 percent), and tongue-ingroove technique was used in 68 patients (27 percent). The mean number of cartilage grafts used in the nose was 1.0 (range, zero to three), and the mean number of sutures used in the nasal tip was 2.81 (range, zero to seven) (Table 3). The preferred suture material for midvault and tip reconstruction in all patients was 5-0 round (16 mm) polydioxanone suture. The most common aesthetic reasons for revision were insufficient nasal tip rotation [n = 95 (37.7 percent)], hanging columella [n = 76 (30.2 percent)], and supratip deformity [n = 72 (28.6 percent)] (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 4). Patients with large bone roof and thick skin structure before the first operation were more prone to Table 3. Other Clinical Findings of Patients Value (%) AQ5 No. of patients Preoperative NL angle, deg Mean ± SD Range Preoperative dorsal hump, mm Mean ± SD Range Nasal tip projection Droopy Normal Elevated Nasal tip rotation Insufficient Normal Excessive Basal tip morphology Triangular Trapezoidal Boxy Preoperative radix Droopy Normal Elevated Spreader flap vs. spreader graft Spreader flap Spreader graft Tongue-in-groove vs. strut Tongue-in-groove Strut No. of cartilage grafts used Mean ± SD Range Cartilage grafts used Dorsal onlay Radix onlay Spreader Spreader and strut Strut No. of sutures used on nasal tip Mean ± SD Range NL, nasolabial. 252 91.29 ± 6.00 73–110 4.04 ± 1.00 1–9 95 (37.7) 156 (61.9) 1 (0.4) 172 (68.3) 79 (31.3) 1 (0.4) 189 (75.0) 31 (12.3) 32 (12.7) 33 (13.1) 207 (82.1) 12 (4.8) 116 (65.9) 86 (34.1) 68 (27.0) 184 (73.0) 1.0 ± 0.4 0–3 2 (0.8) 1 (0.4) 28 (11.1) 44 (17.5) 135 (53.6) 2.81 ± 0.89 0–7 wide dorsum deformity at postoperative follow-up (p < 0.005) (Table 5). Analysis of possible risk factors for dorsal hump deformity showed that thick skin and spreader grafts significantly increased the risk compared with other skin types and spreader flaps, respectively. In addition, it was found that risk was positively correlated with the size of the dorsal hump before the first operation (p < 0.005) (Table 6). It was found that factors such as previous nasal trauma, preoperative deviation, preoperative irregular dorsal aesthetic lines, and the use of spreader flaps instead of spreader grafts could be effective in the emergence of external deviation deformity (p < 0.005) (Table 7). In addition to irregular dorsal aesthetic line and asymmetric nasal tip morphology before the first surgery, factors such as higher number of sutures used at the nasal tip increased the risk of postoperative nasal tip asymmetry (p < 0.005) (Table 8). It was observed that full and bulbous nasal tip morphologies and thick skin caused a fuller appearance at the tip after the operation (p < 0.005) (Table 9). Risk factor analysis for inverted-V deformity showed that wide bone roof before first operation was a risk-increasing factor (p < 0.005). However, dorsal hump amount, skin thickness and spreader flap or spreader grafts used in nasal ridge reconstruction had no effect (Table 10). It was found that the use of tongue-in-groove technique instead of strut graft significantly increased the risk of retracted columella deformity (p < 0.005) (Table 11). The most significant determinants of hanging columella deformity were age older than 40 years and the use of strut grafts instead of tongue-in-groove technique (Table 12). The most significant determinants of supratip deformity were age older than 40 years, using strut graft instead of tongue-in-groove technique, and having low nasolabial angle before surgery (Table 13). Advanced age, low nasolabial angle before operation, insufficient nose tip rotation or projection, and the use of strut graft instead of tongue-in-groove technique were among the factors causing insufficient nasal tip rotation deformity (Table 14). Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate all risk factors that may have an effect on the three most common complications (i.e., insufficient nasal tip rotation, hanging columella, and supratip deformity). Accordingly, for insufficient nasal tip rotation, use of strut graft instead of tongue-in-groove technique increased the risk by T5 T6 T7 T8 T9 T10 T11 T12 T13 T14 750 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Volume 148, Number 4 • Risk Factors for Revision Rhinoplasty Fig. 2. Preoperative photograph of the patient (left); supratip deformity is observed after surgery (center), and 14 months after revision (right). Fig. 3. Preoperative photograph of the patient (left); hanging columella is seen 1 year after surgery (center), and after revision (right). T15 5.3-fold, insufficient nasal tip projection increased the risk by 2-fold, and preoperative low nasolabial angle increased the risk by 0.8-fold. For hanging columella, age older than 40 years increased the risk by 6.8-fold, and using strut graft instead of tongue-in-groove technique increased the risk by 5.9-fold. The use of strut grafts instead of tongue-in-groove technique increased the risk for supratip deformity by 2.2-fold (Table 15). DISCUSSION Revision rates are gradually increasing in rhinoplasty because of increasing patient demands and unrealistic expectations. Because of several features such as disruption of natural anatomy and more difficult dissection by extension, revision surgery poses a greater difficulty than the initial operation. To minimize revision rates, potential risks should be predicted in advance, 751 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery • October 2021 Table 4. Frequency Distributions of Patients in Terms of Prerevision Deformities No. (%) Insufficient nasal tip rotation Hanging columella Supratip deformity (pollybeak) Dorsal hump Broad dorsum External deviation Nasal tip asymmetry Tip fullness Nostril asymmetry Dorsal asymmetry Inverted-V Alar retraction Alar flare Retracted columella Dorsal deviation Depression at facet polygon Nasal ridge asymmetry Dorsal irregularity Insufficient nasal tip projection External valve failure Supraalar notching More than normal rotation 95 (37.7) 76 (30.2) 72 (28.6) 50 (19.8) 44 (17.5) 41 (16.3) 37 (14.7) 20 (7.9) 15 (6.0) 15 (6.0) 14 (5.6) 13 (5.2) 7 (2.8) 7 (2.8) 4 (1.6) 4 (1.6) 3 (1.2) 2 (0.8) 1 (0.4) 1 (0.4) 1 (0.4) 1 (0.4) Table 5. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Wide Dorsum Deformity before Revision No (%) No. Risk factor Spreader flap vs. spreader graft Spreader flap Spreader graft Bone roof Wide Normal Skin thickness Normal or thin Thick Preoperative dorsal hump, mm Mean ± SD Range 208 Yes (%) 0.996* 29 (65.9) 15 (34.1) 111 (53.4) 97 (46.6) 35(79.5) 9 (20.5) 40 (19.2) 168 (80.8) 3 (6.8) 41 (93.2) 4.04 ± 1.03 1–9 4.07 ± 0.89 3–6 No. Risk factor Spreader flap vs. spreader graft Spreader flap Spreader graft Preoperative radix Droopy Normal Elevated Skin thickness Normal or thin Thick Preoperative dorsal hump, mm Mean ± SD Range 0.001* 0.047* 0.856† *Pearson χ2 test. †Mann-Whitney U test. and appropriate measures should be taken accordingly. The revision rates in the present study were similar to those reported in the literature. Literature data indicate that revision of patients with thick skin is more difficult than that of those with other skin types.12,13 In the present study, the majority of patients (82.9 percent) had thick skin. Although skin thickness alone did not increase revision risk for the three most common complications (i.e., inadequate nasal tip rotation, hanging columella, and supratip deformity), if accompanied by other risk factors (e.g., advanced age, strut use, and massive hump resection), it may increase revision risk because No (%) Yes (%) 202 50 p 0.001* 143 (70.8) 59 (29.2) 23 (46.0) 14 (54.0) 27 (13.4) 164 (81.2) 11 (5.4) 6 (12.0) 43 (86.0) 1 (2.0) 42 (20.8) 160 (79.2) 1 (2.0) 49 (98.0) 3.9 ± 0.98 1–9 4.4 ± 1.00 3–7 0.616* 0.002*‡ 0.003†‡ *Pearson χ2 test. †Mann-Whitney U test. ‡Statistically significant. Table 7. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without External Deviation Deformity before Revision No (%) p 44 137 (65.9) 71 (34.1) Table 6. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Dorsal Hump Deformity before Revision No. 211 Risk factor Previous nasal trauma No 177 (83.9) Yes 34 (16.1) External deviation before first operation No 157 (74.4) Yes 54 (25.6) Dorsal aesthetic line Regular 73 (34.6) Irregular 138 (65.4) Spreader flap vs. spreader graft Spreader flap 132 (62.6) Spreader graft 79 (37.4) Yes (%) p* 41 13 (31.7) 28 (68.3) 3 (7.3) 38 (92.7) 0 (0.0) 41 (100.0) <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.012 34 (82.9) 7 (17.1) *Pearson χ2 test. of skin redundancy on the bone and cartilage roof. Neaman et al. found that the full, asymmetric and wide nasal tip morphologies are more prone to revision. Asymmetric tip and tip fullness were two of the most common morphologic disorders observed in revision cases in the present study, which was consistent with the literature (Table 2).5 A higher incidence of wide dorsum deformity in patients with wide bone roof and thick skin was attributed to the relatively wide appearance of thick skin on the dorsum and the potential reopening of the bone roof in the long term, particularly in incomplete osteotomies. Because skin thickness cannot be changed in these cases, this 752 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Volume 148, Number 4 • Risk Factors for Revision Rhinoplasty Table 10. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Inverted-V Deformity before Revision Table 8. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Nasal Tip Asymmetry before Revision No. Risk factor Previous nasal trauma No Yes External deviation before first operation No Yes Dorsal aesthetic lines Regular Irregular Nasal tip morphology before first operation Asymmetric Bulbous Alar flare Hanging columella Footplate flare Tip fullness Unitip Droopy tip No. of sutures used Mean ± SD Range No (%) Yes (%) 215 37 163 (75.8) 52 (24.2) 27 (73.0) 10 (27.0) 139 (64.7) 76 (35.3) 21 (56.8) 16 (43.2) 70 (32.6) 145 (67.4) 3 (8.1) 34 (91.9) 36 (16.7) 26 (12.1) 22 (10.2) 28 (13.0) 21 (9.8) 46 (24.1) 10 (4.7) 38 (17.7) 37 (100) 4 (10.8) 2 (5.4) 7 (18.9) 1 (2.7) 6 (16.2) 2 (5.4) 2 (5.4) 2.7 ± 0.9 0–7 3.5 ± 0.7 3–5 p 0.711* 0.357* 0.002* <0.001* >0.999† 0.546† 0.338* 0.216† 0.472* 0.691† 0.059* <0.001‡ *Pearson χ2 test. †Fisher’s exact test. ‡Mann-Whitney U test. problem can be prevented by fully mobilizing the bones with osteotomies or performing a doublerow osteotomy. A higher incidence of dorsal hump deformity in patients with thick skin, high hump, and spreader grafts was attributed to the thickness of the skin on the dorsum or the upward displacement of the graft resulting from insufficient fixation of the cranial portion of spreader Table 9. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Nasal Tip Fullness before Revision No (%) No. 232 Risk factor Nasal tip morphology Asymmetric 68 (29.3) Bulbous 24 (10.3) Alar flare 22 (9.5) Hanging columella 32 (13.8) Footplate flare 19 (8.2) Tip fullness 40 (17.2) Unitip 11 (4.7) Droopy tip 38 (16.4) Skin thickness Normal or thin 43 (18.5) Thick 189 (81.5) AQ6 *Pearson χ2 test. †Fisher’s exact test. ‡Statistically significant. Yes (%) p 20 5 (25.0) 0.683* 6 (30.0) 0.020†‡ 2 (10.0) >0.999† 3 (15.0) 0.746† 3 (15.0) 0.369† 12 (60.0) <0.001†‡ 1 (5.0) >0.999† 2 (10.0) 0.749† 0.030†‡ 0 (0.0) 20 (100.0) No. Risk factor Spreader flap vs. spreader graft Spreader flap Spreader graft Bone roof Wide Normal Skin thickness Normal or thin Thick Dorsal hump before first operation, mm Mean ± SD Range No (%) Yes (%) 238 14 p 0.393* 155 (65.1) 85 (34.9) 11 (78.6) 3 (21.4) 134 (56.3) 104 (43.7) 12 (85.7) 2 (14.3) 40 (16.8) 198 (83.2) 3 (21.4) 11 (78.6) 4.05 ± 1.01 1–9 3.93 ± 0.83 3–6 0.030† 0.713* 0.533‡ *Fisher’s exact test. †Pearson χ2 test. ‡Mann-Whitney U test. grafts. Because skin thickness cannot be changed in these patients either, it may be preferable to use spreader flaps instead of spreader grafts. If spreader grafts are to be used, special attention should be paid to the fixation of the cranial portion of the graft in the keystone area. A higher incidence of external deviation deformity in patients with previous nasal trauma and deviated and irregular dorsal aesthetic lines before the operation may be attributable to intrinsic memory of cartilage or bone roof asymmetry. In such cases, the use of spreader grafts instead of spreader flaps or the use of additional batten grafts or asymmetric osteotomies may be advantageous for the removal of deviation. Asymmetric nasal tip morphology and increase in the number of sutures used at the nasal tip were directly associated with the risk of nasal tip asymmetry. This was attributed to the intrinsic memory of the nasal tip cartilage and the foreign body reaction caused by the increased number of sutures. Increasing the number of sutures also increases the number of independent variables effective on Table 11. Risk Comparison According to the Technique Used at the Nasal Tip in Groups with and without Retracted Columella Deformity before Revision No (%) No. 245 Risk factor Tongue-in-groove vs. strut Strut 183 (74.7) Tongue-in-groove 62 (25.3) Yes (%) p 7 1 (14.3) 6 (85.7) 0.002* *Fisher’s exact test. 753 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery • October 2021 Table 12. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Hanging Columella Deformity before Revision No. Risk factor Age, yr Mean ± SD Range Age group <30 yr 30–40 yr >40 yr Skin thickness Normal or thin Thick Nasal tip projection Normal Insufficient Nasal tip rotation Normal Insufficient Preoperative radix Droopy Normal Elevated Tongue-in-groove vs. strut Strut Tongue-in-groove Preoperative NL angle, deg Mean ± SD Range Dorsal hump before first operation, mm Mean ± SD Range No (%) Yes (%) 176 76 30.4 ± 7.2 35.6 ± 11.5 18–54 18–56 92 (52.3) 72 (40.9) 12 (6.8) 31 (40.8) 16 (21.1) 29 (38.2) 33 (18.8) 143 (81.2) 10 (13.2) 66 (86.8) 114 (64.8) 62 (35.2) 42 (55.3) 34 (44.7) 59 (33.5) 117 (66.5) 20 (26.3) 56 (73.7) 21 (11.9) 145 (82.4) 10 (5.7) 12 (15.8) 62 (81.6) 2 (2.6) 114 (64.8) 62 (35.2) 70 (92.1) 6 (7.9) 91.1 ± 6.4 73–110 91.7 ± 5.8 78–110 4.1 ± 1.0 2–9 4.0 ± 1.1 1–7 Table 13. Comparison of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Supratip Deformity before Revision p 0.002* <0.001† 0.279† 0.154† 0.258† 0.439† 0.001† 0.661* 0.941* *Mann-Whitney U test. †Pearson χ2 test. wound healing, thereby increasing the likelihood of asymmetry.14 In patients with such asymmetric morphology, asymmetric suture techniques or nonanatomical grafts may be preferred if the surgeon has sufficient experience. The fact that patients with thick skin and a fuller and bulbous nasal tip are predisposed to fuller appearance in the postoperative period was attributed to reduction of the effect of thick skin on nasal tip definition. In such cases, more aggressive cartilage shaping techniques or structural nasal tip grafts may be preferred. A higher incidence of inverted-V deformity in patients with wide bone roofs may be attributable to the reexpansion of the nasal bones (particularly in incomplete osteotomies) during the recovery period following osteotomy. Although there was no difference between the use of spreader grafts or spreader flaps in the middle roof in terms of inverted-V deformity, the use of thick spreader grafts may be a better alternative. In cases of tongue-in-groove technique, a retracted columella is common because of the No. Risk factor Age, yr Mean ± SD Range Age group <30 yr 30–40 yr >40 yr Skin thickness Normal or thin Thick Nasal tip projection Normal Insufficient Nasal tip rotation Normal Insufficient Preoperative radix Droopy Normal Elevated Tongue-in-groove vs. strut Strut Tongue-in-groove Preoperative NL angle, deg Mean ± SD Range Preoperative dorsal hump, mm Mean ± SD Range No (%) Yes (%) 180 72 31.2 ± 8.3 18–55 33.8 ± 10.4 18–56 91 (50.6) 68 (37.8) 21 (11.7) 32 (44.4) 20 (27.8) 20 (27.8) 35 (19.4) 145 (80.6) 8 (11.1) 64 (88.9) 117 (65.0) 63 (35.0) 39 (54.2) 33 (45.8) 60 (33.3) 120 (66.7) 19 (26.4) 53 (73.6) 19 (10.6) 152 (84.4) 9 (5.0) 14 (19.4) 55 (76.4) 3 (4.2) 122 (67.8) 58 (32.2) 62 (86.1) 10 (13.9) 91.9 ± 6.4 73–110 89.6 ± 5.5 73–102 4.0 ± 0.9 2–7 4.2 ± 1.2 1–9 p 0.088* 0.007† 0.112† 0.110† 0.283† 0.167† 0.003† 0.008* 0.241* NL, nasolabial. *Mann-Whitney U test. †Pearson χ2 test. direct fixation of the medial crus to the septum. This complication can be avoided by using maneuvers described by Spataro and Most to reduce this risk.15 They suggested that the fixation suture should be placed to the more cranial part of the medial crus or the more caudal part of the septum to prevent retracted columella deformity after the tongue-in-groove technique. This method reported by Spataro and Most is an effective recommendation for preventing columellar retrusion, in our opinion, in cases where the medial crus craniocaudal width is insufficient, and in cases where caudal septal excess is limited or insufficient, it is more preferable to use strut grafts instead of the tongue-in-groove technique or to use mucosal tongue-in-groove technique if the tongue-in-groove technique will be preferred to prevent retracted columella deformity. In the present study, the most common reasons for aesthetic revision were the events involving the lower (inadequate rotation and hanging 754 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Volume 148, Number 4 • Risk Factors for Revision Rhinoplasty Table 14. Evaluation of Various Risk Factors in Groups with and without Insufficient Nasal Tip Rotation Deformity before Revision No (%) No. 157 Risk factor Age, yr Mean ± SD 30.5 ± 8.4 Range 18–56 Age group <30 yr 86 (54.8) 30–40 yr 52 (33.1) >40 yr 19 (12.1) Skin thickness Normal or thin 31 (19.7) Thick 126 (80.3) Nasal tip projection Normal 116 (73.9) Insufficient 41 (26.1) Nasal tip rotation Normal 67 (42.7) Insufficient 90 (57.3) Preoperative radix Droopy 20 (12.7) Normal 132 (84.1) Elevated 5 (3.2) Tongue-in-groove vs. strut Strut 96 (61.1) Tongue-in-groove 61 (38.9) Preoperative NL angle, deg Mean ± SD 93.4 ± 5.9 Range 73–110 Preoperative dorsal hump, mm Mean ± SD 4.1 ± 1.0 Range 1–7 Yes (%) p 95 34.4 ± 9.5 19–55 37(38.9) 36 (37.9) 22 (23.2) 0.002* 0.020† 0.146† 12 (12.6) 83 (87.4) <0.001† 40 (42.1) 55 (57.9) <0.001† 12 (12.6) 83 (87.4) 0.300† 13 (13.7) 75 (78.9) 7 (7.4) <0.001† 88 (92.6) 7 (7.4) <0.001* 87.9 ± 5.1 73–110 >0.999* 4.0 ± 1.0 2–9 NL, nasolabial. *Mann-Whitney U test. †Pearson χ2 test. columella) and the middle (supratip deformity) one-third portion of the nose. This was attributed to open technique use or nasal tip modifications in most patients. When the most commonly revised nasal areas reported in the literature were examined, it was found that similar results were obtained with our study.3,6,9,16–18 When the risk factors for insufficient rotation, hanging columella, and supratip deformity were examined, it was observed that advanced age (>40 years) and strut graft use were common risk factors in all these cases. Advanced age leads to limited retraction capacity of the mucosa and skin in the postoperative period; consequently, strut grafts are not retracted enough and cannot carry the skin and mucous membranes accumulating on the nose, which may be the underlying cause of these problems. To prevent this problem, three different solutions can be formulated. The first option is not to reduce the cartilage and bone roof above the retraction capacity of the skin (more conservative reduction). The second option is to use more stable fixation methods at the tip of the nose (e.g., tongue-in-groove technique and septal extension grafts). The third option is removal of excess mucosa remaining during surgery from the membranous septum and excision of skin from the columellar incision site. Another reason increasing the risk of insufficient rotation and supratip deformity was found to be preoperative low nasolabial angle. Compared Table 15. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Combined Effects of All Possible Factors That May Be Used to Differentiate between Groups with and without Hanging Columella, Supratip Deformity, or Insufficient Nasal Rotation before Revision 95% CL Hanging columella Age groups (>40 yr) Strut Nasal tip projection Supratip deformity Age groups Strut Skin thickness Preoperative NL angle Preoperative radix Nasal tip projection Insufficient nasal tip rotation Age groups Preoperative NL angle Insufficient nasal tip projection Skin thickness Strut OR Lower Upper 6.861 5.983 1.247 3.011 2.302 0.659 15.634 15.552 2.361 <0.001* <0.001* 0.497 — 2.276 1.261 0.953 — 1.058 — 1.035 0.524 0.905 — 0.564 — 5.004 3.038 1.004 — 1.985 0.082 0.041* 0.605 0.070 0.307 0.861 — 0.857 2.064 0.726 5.308 — 0.801 1.063 0.291 2.138 — 0.917 4.006 1.815 13.178 0.260 <0.001* 0.032* 0.494 <0.001* p CL, confidence limit; NL, nasolabial. *Statistically significant. 755 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery • October 2021 Table 16. Possible Complications and Solution Recommendations Preoperative Finding • • • • • • • • Technique Used Wide bone roof Thick skin Thick skin Spreader graft Dorsal hump Previous nasal trauma Deviated nose Irregular dorsal aesthetic line Asymmetric nasal tip Large number of sutures used on the nasal tip • Thick skin • Full and bulbous nasal tip • Wide bone roof • Advanced age (>40 yr) • Low NL angle Possible Complications • Complete or double row osteotomy Dorsal hump • • • • • • • • • • • • External deviation Nasal tip asymmetry Tip fullness Tongue-in-groove Strut graft Recommendation Wide dorsum Inverted-V Retracted columella Insufficient rotation Hanging columella Supratip deformity Insufficient rotation Supratip deformity Spreader flap Good fixation of the spreader cranial Spreader graft instead of spreader flap Septal batten graft Asymmetric osteotomy Asymmetric suturing techniques Nonanatomical nasal tip grafts Minimum suture use Aggressive nasal tip modification Structural nasal tip grafts Complete osteotomy Modified maneuvers* • Conservative bone-cartilage roof reduction • More stable nasal tip fixation methods (TIG, septal extension grafts) • Mucosa or skin excision • Overrotation • More stable nasal tip fixation methods (TIG, septal extension grafts) NL, nasolabial; TIG, tongue-in-groove. *Spataro EA, Most SP. Tongue-in-groove technique for rhinoplasty: Technical refinements and considerations. Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34:529–538. with patients with normal nasolabial angles, more load is placed on the tip of the nose during surgery, and the tip of the nose may droop over time because of this load in patients with lower nasolabial angles. Insufficient rotation and supratip deformity were believed to be caused by drooping of the tip of the nose. We believe that by analyzing all the risk factors mentioned above, rhinoplasty will be better understood and revision rates can be reduced by taking appropriate precautions during surgery. Health care costs can be reduced, and higher patient satisfaction can be achieved by decreasing the revision rates. The present study is important because it involves a high number of patients treated with similar surgical rhinoplasty procedures. Additional prospective studies and evaluation of patient photographs with three-dimensional modeling systems will increase both the quality and reliability of the study. Further studies have been planned for this purpose. CONCLUSIONS T16 For better clarity, the results of risk factor analysis can be summarized as follows (Table 16): 1. We believe that the use of spreader flaps instead of spreader grafts in middle roof reconstruction in patients with thick skin and a high dorsal hump before the operation would be appropriate to reduce the risk of dorsal hump deformity. 2. Patients with a history of nasal trauma, preoperative external deviation, or irregular dorsal aesthetic lines were found to be more prone to external deviation in the postoperative period. In these patients, spreader grafts should be preferred primarily over spreader flaps. 3. In patients with preoperative asymmetric nasal tip morphology, the risk of nasal tip asymmetry can be reduced by trying to provide nasal tip symmetry with the lowest possible number of sutures. 4. The use of more aggressive nasal tip modifications is required in patients with thick skin and preoperative bulbous or full nasal tip morphology. 5. In patients with advanced age (>40 years), the tongue-in groove technique may be preferred instead of strut graft to reduce the incidence of hanging columella. 6. In patients with advanced age (>40 years) and preoperative low nasolabial angle, the tongue-in-groove technique may be preferred instead of strut graft to reduce the incidence of supratip deformity. 7. Similarly, in patients with advanced age and insufficient nasal tip projection and rotation, it is appropriate to use the tongue-ingroove technique instead of strut graft or to rotate the nasal tip more than normal (overcorrection) to reduce the incidence of insufficient nasal tip rotation after surgery. 756 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Volume 148, Number 4 • Risk Factors for Revision Rhinoplasty 8. If the tongue-in-groove technique is planned in selected patients, it may be necessary to consider the risk of retracted columella and to plan solutions for this problem during surgery. AQ7 Serhat Sibar, M.D. Department of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgery Gazi University Hospital 14th Floor Besevler, Ankara, Turkey serhatsibar@hotmail.com Twitter: @SerhatSibar PATIENT CONSENT Before the study, written consent was obtained from all patients for scientific use of clinical photographs and data in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. REFERENCES 1. Saban Y. Rhinoplasty: Lessons from “errors”: From anatomy and experience to the concept of sequential primary rhinoplasty. HNO 2018;66:15–25. 2. Rohrich RJ, Ahmad J. Why primary rhinoplasty fails. In: Rohrich RJ, Ahmad J, eds. Secondary Rhinoplasty by the Global Masters. New York: Thieme; 2017:3–14. 3. East C, Kwame I, Hannan SA. Revision rhinoplasty: What can we learn from error patterns? An analysis of revision surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2016;32:409–415. 4. Warner J, Gutowski K, Shama L, Marcus B. National interdisciplinary rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:295–301. 5. Neaman KC, Boettcher AK, Do VH, et al. Cosmetic rhinoplasty: Revision rates revisited. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:31–37. 6. Yu K, Kim A, Pearlman SJ. Functional and aesthetic concerns of patients seeking revision rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2010;12:291–297. 7. Cuzalina A, Qaqish C. Revision rhinoplasty. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012;24:119–130. 8. Fattahi T. Considerations in revision rhinoplasty: Lessons learned. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2011;23:101– 118, vi. 9. Parkes ML, Kanodia R, Machida BK. Revision rhinoplasty: An analysis of aesthetic deformities. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:695–701. 10. Kamer FM, McQuown SA. Revision rhinoplasty: Analysis and treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114: 257–266. 11. Daniel RK. Middle Eastern rhinoplasty in the United States: Part I. Primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1630–169. 12. Daniel RK. Middle Eastern rhinoplasty in the United States: Part II. Secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1640–1648. 13. Azizzadeh B, Mashkevich G. Middle Eastern rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2010;18:201–206. 14. Tebbets JB. Secondary tip modification: Shaping and positioning the nasal tip using nondestructive techniques. In: Tebbets JB, ed. Primary Rhinoplasty: A New Approach to the Logic and the Techniques. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:261–441. 15. Spataro EA, Most SP. Tongue-in-groove technique for rhinoplasty: Technical refinements and considerations. Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34:529–538. 16. Parkes ML, Kanodia R, Machida BK. Revision rhinoplasty: An analysis of aesthetic deformities. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:695–701. 17. Bracaglia R, Fortunato R, Gentileschi S. Secondary rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005;29:230–239. 18. Bagal AA, Adamson PA. Revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2002;18:233–244. 19. Rohrich RJ, Afrooz PN. Components of the hanging columella: Strategies for refinement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:46e–54e. 757 Copyright © 2021 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.