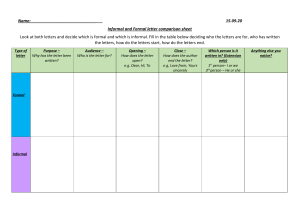

The phenomenon of Informal Urbanisation has become the single most pervasive element of city making in developing countries. The city of Nairobi presents such an urban paradigm. It has however been shown that this urban process is heterogeneous and not homogeneous as propagated by many scholars/researchers. This book raises questions about the role of informality on the urban process of the city of Nairobi. From its establishment, Nairobi's urbanisation has always been characterised by dualism; formal and informal. I argue that informal urbanisation is defined by spatial strategies rather than legal/economic distinctions. The book examines the dynamics of the urbanisation process through case studies, in the four categories of informalities; survival, primary, intermediate and affluent. Diverse Informalities have shown that the informal phenomenon is not entirely negative, as it provides some form of urban livelihood for the poor. This book will be a resource to; Academics in urbanism, Architects and Planners. It will also be useful to urban managers/administrators, policy makers and development agencies among others. Oslo School of Architecture (AHO) Doctoral Thesis. Institute of Urbanism March 2006 i Tom J C Anyamba “Diverse Informalities”; Spatial Transformations in Nairobi. A study of Nairobi’s Urban Process Oslo School of Architecture and Design Oslo – Norway All Illustrations unless otherwise stated have been prepared by the author. ii ABSTRACT This thesis raises questions about the role of informality on the urbanisation process of the city of Nairobi. From its establishment, more than 100 years ago as a transit point for the Uganda Railway, Nairobi’s urbanisation has always been characterised by dualism; formal and informal. Over the years the informal phenomenon has proved to be quite resilient, and has had a profound impact on the urbanisation of Nairobi in the last 30 years or so. Informality has been found to be heterogeneous and not homogeneous as articulated in most literature, and for Nairobi, all socio-economic classes undertake informal processes which I have called Diverse Informalities. I argue that informal urbanisation is defined by spatial strategies rather than legal/economic distinctions. I further make a critique of the legal framework, by reconceptualising the phenomenon through a spatial framework, where space is at the core of the urban processes. Evidence has shown that informal practices manipulate and take advantage of the weaknesses of the legal framework, through spatial strategies. The research examines the dynamics of the urbanisation processes in Nairobi through case studies, in the four categories of informalities, categorised as; survival, primary, intermediate and affluent. These studies provide a more nuanced and accurate description of the informal urban processes in Nairobi, and also show the centrality of space in these processes. The transformations in the Mumias South Corridor, an example of intermediate informalities, illustrate how formal urban settlements gradually informalise over time. They also show the spatial strategies taken by the transformers, which generate new hybrid urbanity. Diverse Informalities have shown that the informal phenomenon is not entirely negative, as it provides some form of urban livelihood for the poor. This thesis also reasserts the centrality of space, and relevance of design in the discussion of the phenomenon of informality. Key words: Urbanism, Informality, Colonial, Spatial, Diverse, Transformations. iii CONTENTS Abstract iii Contents iv List of Figures v List of Tables xii Acronyms xiii Acknowledgements xiv 1. Introduction 1 • Problem Statement 1 • Objectives of study 2 • Research Questions 2 • Justification of Study 3 • Methods 3 • Sources of Data 4 • Choice of Case Studies 5 • Methodological Problems 7 • Organisation of Monograph 7 2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework • Introduction • The Discourse Rooted in Architecture, • • • 8 8 Design and Planning 9 The Discourse Rooted in Urban Social Theory 10 o Early European Urban Theorists 10 o The Chicago School 12 o Contemporary Theorists 13 The Discourse Rooted in Colonial and Traditional Urban Processes 17 The Discourse Rooted in the Informal Urban Process 20 o Evolution of the Concept of Informality 20 iv o Other Debates on Informality • Re-conceptualising Urbanity in Developing Countries • The Evolution of Policies Towards Informal Urbanisation • • • 42 Settlement Demolition Policies 42 o Regularisation Policies 44 o Enablement Policies 47 Re-conceptualising Informality (The Case of “Diverse Informalities) 49 Informality and the Centrality of Space 53 Colonial Nairobi 58 58 o Introduction 58 o The Founding Years 1899-1905 58 o The Consolidation Period 1906-1926 64 o The Intermediate Period 1927- 1946 70 o The Period of Decline 74 Post-Colonial Nairobi 81 o Overall Urban Process 81 o Production and Consumption of Space 91 o Planning, Regularisation and Upgrading 97 4. Diverse Informalities • 27 o 3. The Urban History of Nairobi • 24 Introduction o Common Traits in these Informalities 105 105 106 • Survivalist Informalities 108 • Primary Informalities 118 o Market Stalls (exhibitions) in the CBD 120 o Alecky Fish and Food Kiosk 121 o Hollywood Garage 126 o Mukuru Kwa Njenga Informal Settlement 128 v o Informal Settlements in General 137 • Intermediate Informalities 140 • Affluent Informalities 153 5. Informalising the Formal 162 • Introduction 162 • Evolution of Buru Buru 163 • Planning and Development Control Measures In Buru Buru 169 • Urban Edge Definition 170 • Informalising the Formal 175 o Commercial Transformations 177 o Residential Transformations 185 o Residential cum Commercial Transformations 194 o Transformations of the Shopping Centre 203 o Transformations of the “Mausoleum” 206 o Other Transformations 209 6. Conclusions 211 • Summary 211 • The Urban Process in Nairobi 211 • Re-conceptualising Informality 214 • Merits and Demerits of Informality 216 • Creating a Different Urbanity 220 • Urban Integration 224 • A Critique of Regularisation Policies 227 • The Role of Design in Settlements 228 7. Bibliography 236 8. Appendices 248 vi LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2.1 Nairobi’s Urbanisation Study Model 51 Figure 3.1 Contextual Location of Nairobi 60 3.2 Layout of Nairobi c1900 61 3.3 Layout of Nairobi c1905 63 3.4 Evolution of Biashara Street 64 3.5 Layout of Nairobi c1926 67 3.6 Pumwani: Layout Plan and View 69 3.7 Nairobi Municipal Area c1927 70 3.8 Grid Layout of Eastleigh 73 3.9 1948 Nairobi Central Area 76 3.10 Typical Layout – Neighbourhood Unit 78 3.11 Nairobi City Area 1964 83 3.12 Traffic Jam on Haile Selassie Avenue 85 3.13 NHC’s Tenant Purchase Housing – Pumwani 87 3.14 Matatu Transport – Ronal Ngala/Mfangano Streets 88 3.15 Transformations in Dandora 90 3.16 Informal Modernism – Block 10, Embakasi 91 3.17 Matatu Terminal – Central Bus Station 92 3.18 Informal Nairobi 93 3.19 High Rise Blocks – Mathare North 94 3.20 Transformations of Umoja 96 3.21 Consolidated Enterprise – Block 10 98 3.22 Images of Mathare 4A 101 3.23 Three Dimensional Upgrading – Huruma 102 3.24 Partial Layout – Typical Informal Settlement 103 Figure 4.1 Mama Mboga – South B 4.2 Roadside Flower Pots 112 112 vii 4.3 Roadside Tree Nursery 112 4.4 Blacksmiths 113 4.5 Shoe/Clothes Vendor 113 4.6 Mutindwa Petty Traders 114 4.7 Evolution of a Kiosk 115 4.8 Roadside Maize Roaster 116 4.9 Shauri Moyo – Blacksmiths 116 4.10 Laini-Saba – Traders 116 4.11 Assorted Hardware Dealers 117 4.12 Interior, Nairobi Stalls – Moi Avenue 121 4.13 Stalls – Tom Mboya Street 121 4.14 Kiosks on Road Reserve 124 4.15 Exterior and Interior – Alecky Food Kiosk 124 4.16 Outdoor Fish Stand 125 4.17 A Collage of Kiosks 125 4.18 Hollywood Garage Shed 126 4.19 Clients’ Vehicles 126 4.20 Informal Water Point 128 4.21 Mukuru Kwa Njenga Settlement 129 4.22 Evolution of Mukuru Kwa Njenga 130 4.23 Typical Dwelling – Mukuru Kwa Njenga 132 4.24 Entrance Area – Andimi’s “House” 133 4.25 Interior – Andimi’s “House” 133 4.26 Dwellings under Power Lines 134 4.27 Commercial Pit Latrines 134 4.28 Garbage Heap 134 4.29 Unpaved Roads/Footpaths 136 4.30 Private Health Clinic 136 4.31 Private School (“Academy”) 136 4.32 Location of Informal Settlements 138 4.33 Mathare 4A Dwellings 138 viii 4.34 Roadside Furniture Vending 139 4.35 Matatu Transport 139 4.36 Boulevard – Jamhuri I 143 4.37 High Rise Blocks – Jamhuri II 143 4.38 Fruit Vendor 143 4.39 Jamhuri II - Plot Subdivision Layout 144 4.40 Time Series Images – Jamhuri II 145 4.41 Typical Section – Kinuthia House 148 4.42 Ground Floor Plan – Kinuthia House 148 4.43 First Floor Plan 149 4.44 Entrance View – Kinuthia House 149 4. 45 Stair Detail – Kinuthia House 149 4.46 3 Storey Flats – Jamhuri II 150 4.47 6 Storey Developments – Jamhuri II 150 4.48 Urban Edge Definition 150 4.49 Struggle for Identity 151 4.50 Visual Articulation 151 4.51 Urban agriculture 152 4.52 Main Access Road 152 4.53 Morphological Transformations of Runda 155 4.54 Typical Plot Subdivision – Runda 156 4.55 Layout – Old Runda 157 4.56 Village Market 158 4.57 Food Court – Village Market 158 4.58 Water Fountain – Village Market 158 4.59 Shopping Arcade – Village Market 159 4.60 Main Entrance – Village Market 159 4.61 Aerial View and Site Plan – Plot 97 159 4.62 Ground Floor Plan – Plot 97 160 4.63 First Floor Plan – Plot 97 160 4.64 Sections and Elevations – Plot 97 161 ix Figure 5.1 0m Setback – Phase 1 162 5.2 0m Setback – Phase 2 162 5.3 9m Setback – Phase 4 163 5.4 Transformed 9m Setback – Phase 5 163 5.5 Transformations of Buru Buru 165 5.6 Partial Layout – Mumias South Corridor 168 5.7 Urban Edge Definition 2 171 5.8 Commercial Transformation 172 5.9 Residential Transformations 172 5.10 Commercial cum Residential Transformations 172 5.11 Urban Edge Definition 3 174 5.12 Layout – Cluster A 175 5.12b Layout Cluster A – Phase 4 Junction 176 5.13 Transformations on 2/496 178 5.14 Transformations on 2/858 180 5.15 Transformation on 4/174 181 5.16 Balcony on 2/496 182 5.17 Drying Area 2/858 183 5.18 Annexed Passage Adjacent to 2/858 183 5.19 Entrance -.Drycleaners 2/858 183 5.20 Millennium Clinic Access 4/174 184 5.21 Dental Room 4/174 184 5.22 Entrance Area 4/174 184 5.23 Reception 4/174 184 5.24 Transformations on 4/201 186 5.25 Entrance View 4/201 187 5.26 Lawn/Drying Area 4/201 187 5.27 View from Access Road 4/201 188 5.28 Transformations on 5/437 189 5.29 Original and Transformed Constructions 5/437 190 5.30 View from Spine Road 5/437 191 x 5.31 Interior – Hair Saloon 5/437 191 5.32 Ample Car Parking 5/437 192 5.33 Transformations - Cluster B 193 5.34 Double Storey Extensions – Cluster B 194 5.35 Demolished 3-Storey Extension 194 5.36 Transformations on 2/814 195 5.37 Video Library 2/814 196 5.38 New Architectural Character 196 5.39 Transformations 4/281 198 5.40 Narrow Gap between Old and New 199 5.41 Cantilevered Balconies 199 5.42 Transformations on 4/284 200 5.43 Interior – Cyber Café 4/284 201 5.44 Interior – Hair Saloon 4/284 201 5.45 Phased Transformations 4/284 202 5.46 Shopping Centre 2003 203 5.47 Shopping Centre Transformations – Cluster D 204 5.48 External Balconies Internalised 205 5.49 Informal Market 205 5.50 Transformations – “Mausoleum” 207 5.51 Ukweli Fabricators 208 5.52 Buru Buru Centre 208 5.53 Recent Developments 209 5.54 Supermarket – Tusker Mattresses 209 5.55 Tents Pub – Interior 209 5.56 Converted Disused Container 209 5.57 Tents and Winds Pubs 210 Figure 6.1 Commercial High Rise Developments 219 6.2 Cerda’s Minimum Urb 230 6.3 Typical Courtyard Layout – Buru Buru 231 xi 6.4 Sections – Professional Intervention 232 6.5 Sections – Design Options 234 6.6 Sections and Layout – Design Options 235 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Nairobi’s Area and Population 82 2. Residential and Population Densities 84 3. Categories and Salient Attributes of Diverse Informalities 107 4. Global Development Paradigms and Their Characteristics 221 xii ACRONYMS AHO Oslo School of Architecture CARDO Centre for Architectural Research and Development Overseas CBD Central Business District CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CIAM International Congress of Modern Architecture HBE Home Based Enterprise HRDU Housing Research and Development Unit MGS Metropolitan Growth Strategy MNC Multi National Corporation NACHU National Cooperative Housing Union NCC Nairobi City Council NHC National Housing Corporation NISCC Nairobi Informal Settlements Coordination Committee NUFU Norwegian Council for Higher Education SAPs Structural Adjustment Programmes SEARCH Southern and Eastern Africa Research Cooperation for Habitat UNCHS United Nations Centre for Human Settlements. UNDP UON United Nations Development Programme University of Nairobi xiii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank the Norwegian Council for Higher Education (NUFU), and the Higher Education Loans Board (Lånekassen), for funding the doctoral study and the writing of this dissertation. I am indebted to the SEARCH team of; Sven Erik Svendsen, Ola Stave, Steinar Eriksrud and Inger Lise Syversen, for initiating the co-operation between Norwegian and African Universities, a co=operation that led to this study. I thank the University of Nairobi for granting me study leave, and for enabling me to come to Oslo to pursue this study. In particular I wish to thank the Chairman Department of Architecture, UON, for facilitating the carrying out of empirical studies. My advisors at AHO; Karl Otto Ellefsen and Edward Robbins guided and gave me insightful remarks throughout the study period, and I wish to thank them. I acknowledge the criticism of Winnie Mitullah, my UON advisor, which helped shape this thesis. I also acknowledge the support of the PhD programme staff at AHO; Halina Dunin-Woyseth, for her guidance during the research education phase and Ingunn Gjørva for handling all administrative matters. Many thanks to Berit Skjaervold for taking care of visas, permits and loans, and the AHO IT team for making sure that all was well with computers. The input of Jarrett Odwallo and Joseph Mukeku in data collection is also recognised plus the work of Evans Otieno, who tirelessly digitised all the drawings of this study. My gratitude and recognition to the settlers of Mukuru Kwa Njenga, Jamhuri II, Buru Buru and Runda, who are creating a different urbanity, that has informed this thesis. My colleagues on the PhD programme; Wilson Awour, Tom Sanya, Ezekiel Moshi and Cyracius Lwamayanga added value to my stay in Oslo. The larger Anyamba family in the Diaspora has always supported and encouraged me, and I wish to thank them. I thank my son Anyamba, daughters Iranji and Kadenge for their understanding and patience while I was away. Last but not least, I thank my wife Nyaranga, for her patience and endurance of my long absences, and for taking responsibility of the family during this period. Finally I take all the responsibility for any shortcomings of this thesis. xiv 1. INTRODUCTION Problem Statement The phenomenon of informal urbanisation has become the single most pervasive element in the production of cities in developing countries. The shear magnitude of this modality of city making has rendered it as the norm rather than the exception in the growth of contemporary cities (Castillo, 2000:2). The city of Nairobi represents such an urban paradigm, with an area of approximately 690km² and a population of over 3 million people, where 60% of the population lives in informal settlements. Further more, this 60% of the population is crammed into only 5% of Nairobi’s residential land area, on land which is predominantly marginal (Matrix Development Consultants, 1993; NISCC, 1997; Syagga, 2002). Informality has become the basis for city making in Nairobi for the last 30 years or so, as opposed to formal development. This urban process, however I will argue is not homogeneous as alluded to by most literature but rather heterogeneous. It is this informal heterogeneous urban process taking place in Nairobi that I seek to unpack. Ordinarily, the phenomenon of informality has been associated with the urban poor, based on the ecological theories of the “Chicago School”. Their successors, the neo-liberal urban economists, regarded slums as the natural response of the market in providing housing for poor people: the housing they can afford. Poverty and slums are closely related and mutually reinforcing (UNCHS, 2003:2). Other scholars have seen the phenomenon of informality as the source of illegality. In this regard, Mitullah and Kibwana have argued differently, they posit that illegality can be conceptualised purely on professional lines: The cities which the poor build and in which they live and work are different from and unrelated to what the city authorities want built (Mitullah and Kibwana, in Fernandes and Varley, 1998: 193). Hernando De Soto on the other hand argues that the phenomenon of informality should be seen through the prism of capital. He posits that because most people in Third World and ex-communist countries are unable to capitalise their property, they resort to 1 extralegal arrangements of carrying out their businesses in the absence of affordable legal means. These arrangements however have a disadvantage in that they are not integrated into the formal property system and as a result are not fungible and adaptable to most transactions; they are not connected into financial and investment circuits; and their members are not accountable to authorities outside their own social contract (De Soto, 2001: 90). These concepts of city making are what I set out to investigate using the city of Nairobi. The study of informality through legal and capitalistic frameworks will be addressed, but much more important, I plan to add the spatial dimension to this study, which I hope will make the debate more holistic. This is in recognition of the fact that informal urban processes do not take place in a vacuum, but rather in space. This study will also investigate whether players/actors in informal processes take legal or spatial strategies in their effort of accessing urban goods and services. Objectives of Study The main objective of the study is to try and unpack the informal urban processes generating the urban fabric of Nairobi. In this regard a clear understanding of the informal spatial transformations taking place in all spheres of society is sought. The study also aims at documenting some informal transformations that have taken place in Nairobi in the last 30years or so. In conclusion, mitigating factors/variables for this urban condition will be addressed. Research Questions The main research questions are:• How and why is the informal urbanisation process taking place in Nairobi? • Who are the key players and variables in this process? • What is the impact of this process on Nairobi’s urban fabric? • What measures can be put in place to mitigate this urban condition? 2 Justification of Study The study of the informal urban process with an emphasis on the spatial dimension of informality will contribute to the literature on human settlements. This study will also go beyond the traditional boundaries, where informality has been associated with the urban poor. By examining the informal urban process taking place among the middle and high income groups in Nairobi, new insights on the phenomenon of informality, it is envisaged will be unveiled. The detailed study focusing on informalising the formal (ex-formal), and the intermediate informalities producing new settlements, will generate new epistemological underpinnings of informality, further enhancing our understanding of the phenomenon of informality. Methods This study combines grounded theory and case study methods. Grounded theory allows for the development of theory through different stages of data collection and the refinement and interrelationships of categories of information (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). The development of theory is not the origin but rather the outcome of the research. While certain analytical concepts surface during the research process, they are always challenged, compared, and thought of in non-standard ways. The purpose of using a grounded theory method is to close the gap between theory and empirical research. Portes speaks of grounded theory as “the renovation of conceptual tools to apprehend an elusive, shifting reality”. He adds that; It is often necessary to abandon the comfort of familiar definitions and theories and formulating new and frequently imperfect ones…..which although untidy, will take us closer to the understanding of events (Portes et al. 1989:4). Grounded theory was used in the theoretical stages of this dissertation as is evident in chapters one and two, particularly in developing Nairobi’s urban study model Fig.2.1. Grounded theory also came in handy in analysing the material from the case study areas and in deconstructing informality into “diverse informalities”. The case study research allowed a more detailed explanation of the particularities in each of the study areas. Case study is defined by Yin; 3 As an empirical enquiry that seeks to understand a contemporary phenomenon in its real life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not evidently clear and in which multiple sources of evidence are used. Yin’s statement is complimented by Bell, 1993:8 who itemizes case studies as explanatory, descriptive or exploratory. While researcher’s concern in an exploratory case study is seeking new ideas or insights on the phenomenon being studied, a descriptive case study deals with issues or events which have or are taking place. Explanatory case studies, however seek to develop or unveil the cause-effect of the studied phenomenon. In studying spatial transformations in Nairobi, the study will be both explanatory and exploratory. The main aim of this study is to enquire into how informal transformations are taking place in Nairobi generally and in particular in formally designed settlements. The study explores the factors influencing transformations and the implications of these transformations on the built fabric of Nairobi. This work seeks to comprehend the people’s attitudes to the mismatch between their needs and the provision of urban services. It also seeks to document the type of mix-use developments that are resulting from these informal urban transformations. The informal/formal socio-spatial analogy will be the basic theoretical tool for analysing the urban process in Nairobi. In addition, morphological transformations of Nairobi’s urban tissue will be analysed using both synchronic and diachronic methods.1 Sources of Data Grounded theory has the advantage of flexibility in data collection and the interaction between concepts. It allows for the sources to range from historical records, to interviews and observations. The method allowed the data collection for this research to be varied. The sources ranged from theoretical literature on the phenomenon of informal urbanisation and urban research on the city of Nairobi; to the analysis of maps, plans, drawings, photographs, aerial photographs, digital images; census data; as well as indepth interviews with key informants. 1 See for example Samuels, I. et al. 2004; Castex, J. 1979; Moudon, A. V. 1997. 4 I sourced the time series aerial photographs from the Survey of Kenya, while the digital images were sourced from the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD). Land use maps and plot subdivisions were sourced at the Lands Office-Ardhi House, and at the National Housing Corporation (NHC). Hard copy archival drawings for Buru Buru were sourced at City Hall, and then digitised. Other drawings were sourced from project consultants and some key informants. In addition I shot all the photographs of the study areas included in this dissertation in the two year period from 2003 to 2005. Census data was sourced from the Republic of Kenya, Central Bureau of Statistics publications on population and housing census. Finally an additional source was the measured drawings and in-depth interviews carried out from 2003 to 2005 with different players/actors in the various study areas including settlers, planners, authorities and opinion leaders. Choice of Case Studies The initial idea was to select two or three study areas/settlements that depicted intensive spatial transformations in the last 10 years or so. This was to be done by identifying the relevant tools for carrying out the research such as availability of literature, graphical and other visual material. A pilot study was carried out in the period February 2003 and July 2003, this study was supposed to identify the areas/settlements that were to comprise the case studies. The pilot study showed that the phenomenon of informality in Nairobi was complex, and therefore, carrying out a generalised study could not create a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, this called for a new strategy. However, it became also clear that many planned residential areas were being informalised, and that study data for some of these areas could be pieced together. I then spent the later part of the pilot study period on collecting data on Buru Buru estate, a formally designed middle income estate that was undergoing rapid transformations. The data was collected on two levels; the first level was in identifying the origins of the settlement, who, why and how it developed, and its evolution over time. The second level focused on the central issue of this thesis i.e. urban space. The inquiry into urban spatial transformations included data at overall layouts and spatial features of the settlement, 5 infrastructural services and most importantly the transformations at lot level. The lot/plot as the smallest identifiable unit in the settlement became my basic unit of analysis. All along the guiding questions during the spatial analysis were; how is informal urbanisation impacting on the urban fabric and services, which are the key players and variables in this process. In addition at the lot level, the questions were; what kind of architectural character is evolving and who are the main actors at this level of the urban process. Further literature review on the phenomenon of informality and exposure to grounded theory, allowed me to restructure the study into for categories of informality: survivalist, primary, intermediate and affluent. This was because the pilot study showed that informality in Nairobi was not homogeneous but heterogeneous or diverse. This led to the further development of the study into “diverse informalities”, as informal practices in Nairobi are not a preserve of the urban poor but cut across all socio/economic classes, and are therefore diverse. Armed with the above knowledge/background, I was able to embark on the second empirical study with a clear focus on which areas/settlements to interrogate. The Buru Buru case was categorised as intermediate where the settlement was being modified. I then had to identify the survivalist, primary and affluent categories including an intermediate category where the settlement was being formed. Since the survivalist category is mobile/transient, I could look at various examples to be found all over the city. The kiosks at the entrance to Imara Daima estate and the adjacent Mukuru Kwa Njenga informal settlement were selected as the cases for primary informalities. Jamhuri 2 estate, a new settlement formation was identified to form part of the intermediate informalities case. Runda estate completed the choices as the case for affluent informalities. The spatial analyses of these settlements/areas were made by using time series aerial photographs while the detailed morphological unit transformations were also documented. In all the cases, the impact of the informalities on infrastructure and built fabric was consistently analysed. Spatiality being at the core of this thesis, necessitated that spatial transformations at the unit level were also observed in terms of; use of materials and 6 technology, and who were the actors in each situation. Grounded theory made it possible to document, collect and compare data from these varied sources. Methodological Problems The main problem encountered was that, most settlements are not documented; I therefore had to spend time making measured drawings, which were later digitised. The other problem was that many people are not willing to be interviewed let alone give permission for their premises to be photographed. This made me change the strategy of field data collection, by focusing on using key informants and opinion leaders. With regard to literature, some secondary sources present empirical evidence that is sometimes contradictory. This made it necessary for me to look at different traits of the same phenomenon, and thus organising the sifting process. The validity of responses through interviews can also be problematic; however this was overcome by the strategy of using key informants. The approach of using key informants helps to create the necessary rapport, thereby eliminating the possibility of getting false responses. Organisation of Monograph The monograph is divided in six chapters. Chapter one which is the introduction deals with; the problem of informality, objectives of the study, research questions, justification of study, organisation of monograph and research methods. Chapter two tackles the theoretical and conceptual framework of the study, where Nairobi’s urban study model is developed. It highlights the theoretical debates on informality and argues for the place of “diverse informalities”. Chapter three looks at the urban history of Nairobi and the processes that led to the failure of planning and the emergence of informality. Chapter four focuses on “diverse informalities”, starting with survivalist informalities through primary, intermediate to affluent informalities. Chapter five covers the detailed study area of the Mumias South Road corridor, and addresses the issue of informalising the formal. Chapter six covers the conclusions with bibliography and appendices concluding the write up. 7 2. THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK Introduction In this chapter, I explore the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings that will anchor the discourse on Nairobi’s urban process. In order to set the context for this, it is necessary to briefly discuss the “Western Capitalist City Model”2, which historically has been the basis for the design and development of Nairobi. Nairobi’s planning and development proposals over the years, have been in the interests of the business and ruling elite, and have tended to marginalise the urban majority. This urban majority were predominantly the African labour force during the colonial period. Although after independence, the European elite were replaced by the emerging African bourgeois, the urban majority remained the African workers and new masses of unemployed people. Subsequent post-colonial initiatives for the development of Nairobi continued to marginalise this urban majority, who have had to seek alternative means of survival.3 It is for the above reasons among others that the theories that have informed the development of the “Western Capitalist City” are discussed. This Western Capitalist or Market based city model, ignores most of the urban processes in cities of developing countries. The theories informing the Western City are discussed at two levels; the first level being the theories rooted in architecture, design and planning. The second level of discussion focuses on urban social theory. I then follow up with a discussion on colonial and traditional urban processes, which leads to the discussion on informal urban processes. Re-conceptualising urbanity in developing countries is then discussed, leading to the discussion on the evolution of policies towards informal urbanisation. Re-conceptualising informality (The case for “Diverse Informality”), is then considered before closing the chapter with a discussion on informality and the centrality of space. What now follows is the discourse rooted in Architecture, Design and Planning. 2 The 1927 Plan for the Settler Capital was based on South African Examples, while the 1948 Master Plan for a Colonial Capital was comparable with the city plans of Paris, Canberra, Washington, Pretoria, Cape Town and New Delhi – Thornton White, et al. 1948: 59. 3 The spatial transformations taking place in Nairobi are basically transformations of the colonial capitalist city. These transformations are evolving a new spatial model in conditions of limited resources. 8 The Discourse Rooted in Architecture, Design and Planning In discussing the urban process, I start with the discourse rooted in architecture, design and planning. From a historical perspective, the debate rooted in architecture, design and planning, gained its momentum during the industrial revolution, when the medieval/classical city was supposed to be transformed, in order to satisfy the new requirements of industrial society. The epidemics of 1830s and 1840s in Europe had the effect of precipitating health reform and bringing about some of the earliest legislation governing the construction and maintenance of dense conurbations. The Public Health Act of 1848 in Britain, in addition to others, made local authorities legally responsible for sewage, refuse collection, water supply, roads, the inspection of slaughter-houses and the burial of the dead (UNCHS, 2003:74). Similar provisions were to occupy Haussmann during the rebuilding of Paris between 1853 and 1870. According to Haussmann, the basic problems of Paris were; polluted water supply, lack of adequate sewage system, insufficient open space for both cemeteries and parks, large areas of squalid housing and congested circulation. Haussmann’s radical solution to the physical aspect of Paris’ complex problems was “percement” (wholesale demolition in a straight line to create entirely new streets). His broad purpose was, as Choay has written, “to give unity and transform into an operative whole, the huge consumer market, and the immense workshop of the Parisian agglomerate”. Similarly, in Barcelona, the regional implications of urban regularisation were being developed by the Spanish engineer Ildefonso Cerda` the inventor of the term urbanizacion (Frampton, 1992). For Cerda`, transit was, in more ways than one the point of departure for all scientifically-based urban structures. In 1867, Cerda` formulated a general theory of urbanisation, which resulted in what he referred to as the Complete, Integrated City. His main concern was the creation of healthy housing as a first prerequisite for the creation of a new industrial city (Government of Catalonia, 2001). In 1882, Arturo Soria proposed the Linear City, believing that a linear city form was best suited to optimising locomotion (Velez, D. 1982/83:131-164). Subsequently in 1889, Camillo Sitte proposed the Cultural City, which was an attempt to recover a lost artistic vision, and the highlighting of monuments by judicious use of squares and perspectives (Sitte, C. 1889, Translated by Collins G. R. and Collins, C. C. 1965). The search for an 9 appropriate city model continued, and in 1898, Ebenezer Howard proposed the Garden City (Hall, P. and Ward, C. 1998) as a blend of town and country, then Tony Garnier followed in 1901 with the proposal for the Industrial City, which emerged to address the growing need of making industry the motor of urban life (Wiebenson, D. 1969). Later on in America, the 1935 proposals of Frank Lloyd Wright for the Broad Acre City had a lot of influences from Howard’s earlier work (Wright, F. L. 1945). The foregoing not withstanding, the urbanisation paradigm that has had a profound influence in the 20th century was Le Corbusier’s 1943 proposal for a Rational City. This was a functional solution with four main functions – habitation, work, rest, and movement, based on these functions, zoning was established as an urban planning practice (Jenks, C. 1987). In later years, rather than search for appropriate city models, many scholars/practitioners were pre-occupied with urban analysis; for example, Rossi’s 1982 urbanisation discourse in his publication; “the Architecture of the City”, is an attempt at formulating an architectural language for analysing the city. He studies the city as spatial structure, as derived from architecture and geography, as opposed to the city as urban space, which is derived from an analysis of political, social and economic systems. The key question in Rossi’s debate being, what composes a city? Scholars such as; Rob Krier, Leon Krier, Rem Koolhaas and others have been pre-occupied with contemporary urbanity. From the above discussion, it is evident that Social-spatial considerations were at the core of the Western Capitalist urban process, as opposed to legal frameworks. I now turn to the discourse rooted in urban social theory. The Urban Social Theoretical Discourse Early European Urban Theorists Parallel to the debates rooted in architecture design and planning, there were other social theoretical debates on the city. These debates yielded certain theories on the urban condition under capitalism. The beginning of the urban social debates can be traced to the work of Karl Marx and Frederich Engels. These two theorists worked at a time when Western society was changing from a feudal to a capitalist society, and the city was becoming the centre of capitalist production and consumption. 10 The work of Karl Marx, particularly his later theoretical discussion of capitalism has formed the basis for some of the most important contemporary discussions on the city. For example the work of David Harvey, Henri Lefebvre and Manuel Castells have been shaped by the work of Marx. Especially Harvey and Lefebvre who have adopted Marxian approaches as a corrective to what they see as the disruptive, and theoretical as well as moral limits of other theories (especially neo-ecology) (Callinicos, A. 2004). While Marx focused on capital, Engels was more concerned with the problems of the city especially as they expressed the conditions of living for the labouring classes and as a part of the issue of housing so central to many debates about the nature of reform and society in the 19th century. For Engels, redesigning the city, reforming its mechanisms and politics while necessary can only come about through a revolutionary change in which capitalism is replaced by socialism. Engels (like Marx) saw the city as a critical moment in the development and creation of capitalism. Thus for Engels, the very nature of the city is not some accident or mistake open to reform, but the immirseration of its masses represents at its core the very logic of capital (McLellan, D. (ed.), 1993). Max Weber was another early theorist to theorise the condition of the city. Weber’s work on social theory offered the most corrective and alternative to Marx and Engels among modern social theorists. Weber, a key figure in the development of European sociology and political theory, had much to say about the city. If Marx was the revolutionary thinker looking for a theory of praxis and social transformation, Weber was the liberal theorist looking at modern society from an entirely different set of lenses. The basic tenet of Weber is that individuals act with free will and in their interaction with others they seek to realise certain objectives or values. Sociology is about what people achieve and the strategies which most likely yield the desired affects. At the heart of Weber’s sociology, is the notion that sociology is the “interpretive understanding of social action”. Weber rejects the notion that size and density defines the city. The city as he defines it is done as a series of ideal types. A city for Weber is best understood in terms of its political and economic role and organisation. Weber’s city typology was the late medieval city state which is critical to Weber because his interest in the city is as an institution that would free European society from what he saw as the shackles of 11 feudalism. Thus for Weber as for Marx, the discussion of the city is really part of a larger discussion of capitalism (Martindale and Neuwirth, 1958). On the other hand, Georg Simmel like many theorists of the late 19th century was concerned with the shifting nature of social and cultural relations with the shift from a more rural to a more urbanised society. Simmel emphasises the psycho-social split between community and urbanity. Simmel sees the breakdown of the city as a result of the growth of population and its effects on social relations – the dialectic shift of quantity into quality. Like Marx, he sees the roots of this shift in the transformation of the economy – most notably the importance of money as the key element of exchange in the shift from communities to civets. Simmel like Marx and Weber wrote at a time of great upheaval (19th/20th centuries). It was a period of rapid advances in industrialisation, communications and transportation. Cities were growing exponentially and society was shifting to one based on industrial production, increasing ploritarianisation of the labour force and the demise of the rural peasant agricultural and craft systems of work. These shifts transformed the way people associated, located and defined themselves (Frisby, D. 1994). The Chicago School The Chicago School of Sociology attempted to sketch an organic theory of urban form, a process which left us with an ideological and investigative field, which still influences the ways we understand, imagine and plan our cities. The Chicago School also left a collection of important case studies and ethnographic accounts of some of the richest and poorest urban communities in Chicago and elsewhere. Although the work of the Chicago School is a genuine shift in interest and approach, many of the images of their city and their notions of what and why a city works the way it does resonates with the work of Georg Simmel. Manuel Castells notes 50 years later, that the work of the Chicago School is the first to ground and locate the city as place or territorial unit. The Chicago School developed a general ecological theory of cities, where it was believed that at the base of human society is a community, a natural, unplanned symbiotic grouping based on proximity, kinship and common interactions. This ecological order is made of independent individuals each with a place in a hierarchical pecking order in 12 which each member has a function. Competition helps create order as each part functions for the whole because each community is in competition with all others (Tomasi, L. 1998). Contemporary Theorists David Harvey Whereas the late 19th century and early 20th century theorists were concerned with the conditions of the industrial city, the post 1960s theorists addressed the urban condition of the high-tech globalising era. One such theorist among others is David Harvey. Harvey a Marxist theorist is interested in understanding the forces that frame the urban process and the urban experience under capitalism. In his book “Consciousness and the Urban Experience”, he interrogates the city through the prism of money, time and space. The rationality of money and the power of interest, the partitioning of time by the clock and of space according to the cadastral register, are all abstractly conceived features of social life. Yet each in its own way seems to have more power over us than we have over them (Harvey, 1986:1). Harvey argues that the demands to liberate space from its various forms of domination, to liberate time for free use, and to exist independently of the crass vulgarity of pure money valuations can each be built into social protest movements of enormous breadth and scope. Yet creative use of money, space, and time also lies at the heart of constructive urban experience (Harvey, 1986:2). On the spatial dimension of capitalism, Harvey observes that: The accumulation of capital has always been a profoundly geographical affair. Without the possibilities inherent in geographical expansion, spatial reorganisation, and uneven geographical development, capitalism would long have ceased to function as a political-economic system. The perpetual turn to a “spatial fix” to capitalism’s internal contradictions coupled with the uneven insertion of different territories and social formations into the capitalist market, has created a global historical geography of capital accumulation whose character needs to be well understood (Harvey, 2000:23). 13 The spatial fix was made possible by the invention of cadastral survey that enabled the unambiguous definition of property rights in land. Space thus came to be represented, like time and value, as abstract, objective, homogeneous, and universal in its qualities. What the map makers and surveyors did through mental representations, the merchants and land owners used for their own class purposes (Harvey, 1986:13). They were able to buy and sell space as a commodity. This act of buying and selling space, made it possible to bring space under the single measuring rod of money value. In addition, now that space could be demarcated and commoditised, builders, engineers and architects for their part showed how abstract representations of objective space could be combined with the exploration of concrete , malleable properties of materials in space (Harvey, 1986:13). Based on Marx’s and Engels’ somewhat ambivalent approach to capitalist space, Harvey shows that rhetorical mode of geographical restructurings tend to privilege time and history over space and geography (Harvey, 2000:24). However, Lefebvre makes a counter argument in his debate on social space. He argues that; Economic space sub-ordinates time, whereas political space eradicates it because it is threatening to existing power relations. The primacy of the economic, and still more the political, leads the supremacy of space over time (Lefebvre, 1979:147). For Harvey, urbanisation concentrates productive forces as well as labour power in space, transforming scattered populations and decentralised systems of property rights into massive concentrations of political and economic power that eventually consolidated the legal and military apparatus of the nation state. Nature’s forces are subjected to human control as transport and communication systems, territorial divisions of labour, and urban infrastructures are created as foundations for capital accumulation (Harvey, 2000:25). The consequences of concentrating the proletariat in factories and towns are that; they are made aware of their common interests. On this basis they begin to build institutions, such as unions, to articulate their claims. 14 Harvey has also argued that money can be converted into social power, and to some degree, space and time are also forms of social power. Their control could all too easily degenerate into a replication of forms of class domination that the elimination of money power was supposed to abolish (Harvey, 1986:32). On this basis, the control of space and time is the reason why car and homeownership make such an attractive combination as it ensures an individualised ability to command time and protect space simultaneously (Harvey, 1986:13; Castells, 1978:31). Finally Harvey observes that; Capitalism these last two hundred years has produced, through its dominant form of urbanisation, not only a “second nature” of built environments even harder to transform than the virgin nature of frontier regions years ago, but also an urbanised human nature, endowed with a very specific sense of time, space, and money as sources of social power and with sophisticated abilities and strategies to win back from one corner of urban life what may be lost in another (Harvey, 1986:35). Other Theorists Many theorists have been debating the urban condition in the 20th century. I now highlight a few of these theorists, by articulating the salient issues they raise in their debates. Manuel Castells addresses the urban phenomenon through the lenses of “social movements”. Castells sees cities as a residential form adopted by those members of society whose direct presence at the places of agricultural production was not necessary. That is to say, these cities could exist only on the basis of the surplus produced by working the land. They were religious, administrative and political centres, the spatial expression of social complexity determined by the process of appropriation and reinvestment of the product of labour (Susser, 2002:23). In discussing the city, Castells uses the concept of collective consumption, and illustrates the resulting urban contradictions in advanced capitalism. Henri Lefebvre, a Marxist theorist on the other hand debates the production of “Social Space”. He asserts that; the production of space, in concept and reality, has only recently 15 appeared, mainly, in the explosion of the historical city, the general urbanisation of society, the problems of spatial organisation and so forth. Today, the analysis of production shows that we have passed from the production of things in space to the production of space itself (Lefebvre, 1979:141). For Lefebvre, space has its own reality in the current mode of production and society, with the same claims and in the same global process as merchandise, money and capital. He posits that; Capitalism and neo-capitalism have produced an abstract space that is the reflection of the world of business on both national and international levels, as well as the power of money and the “politique” of the state (Lefebvre, 1979: 143). Lefebvre further argues that capitalist space can be used as; a means of production, an object of consumption and as a political instrument. The dominance of the capitalist space has led to class struggles, and the intervention in its production. This intervention would lead to the production of socialist space, which means; The end of private property and the states political domination of space, which implies the passage from domination to appropriation and the primacy of use over exchange (Lefebvre, 1979:149). Edward Soja is another theorist, who discusses the city through the paradigm of postmodernity, where the urbanisation process is changing, but also maintaining continuity with modernity. A condition he refers to as a shift from the Fordist to the postfordist urbanisation (Soja, 1994). Soja asserts that space in the social sciences, has also returned as a key analytical tool. He argues that in it is in space, and not necessarily history, where some of the most insightful perspectives can be found. The production of spatiality in conjunction with the making of history can thus be described as the medium and the outcome, the presupposition and the embodiment, of social action and relationship, of society itself. Social and spatial structures are dialectically intertwined in social life, not just mapped one on to the other as categorical projections (Soja, 1989:127). Graham and Marvin discuss the post modern city in their book “Splintering Urbanisms”, by focusing on the networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the emerging urban condition. They construct a parallel and cross-cutting perspective of urban and 16 infrastructure change, and show that modern urbanism is an extraordinarily complex and dynamic socio-technical process (Graham and Marvin, 2001). The discussion by early European urban theorists on the urban condition of the Western City, although generally abstract, and mainly focusing on capital, directly illustrates how capital impacts on urban space. This in effect makes the discussion of capital congruent with the discussion of urban space. In fact, as was shown, Harvey addresses the spatial dimension of capital. Furthermore, most contemporary theorists discussing the urban condition, mainly focus on the spatial dimension of urbanity. The above debates are rooted in the urban condition of the Western Capitalist or Market based city. As discussed earlier, these debates ignore much of the urban process in developing countries. I now discuss the colonial and traditional debates that address to some degree the urban process in developing countries. The Discourse Rooted in Colonial and Traditional Urban Processes From the very beginning, colonial urbanisation was based on authoritarian city planning which emerged in Sub-Saharan Africa from the 1920s and 1930s, and exploded from the 1950s. It should be noted that “the concept of colonial cities as urban laboratories is important in terms of urban theory, legislation, and actual policies” (Wright, 1987, quoted in Coquery-Vidrovitch, 1991:68). Colonial cities were used as experimental fields, to try and improve urban models born in Europe from European professionals combining modernism in architecture with the idea of integrating cultural phenomena into social and political history. These kinds of experiments at the time could not be attempted either in England or France, but only in the colonies (Vidrovitch, 1991:68). The so-called spontaneous settlements, did not originate in the post-colonial mushrooming cities of today. They were from the beginning a structural part of colonial realities. The concepts ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ are useful as long as one recognises that informal practices are both constituted by, and must be analysed in relation to, formal practices. Several scholars have also addressed the phenomenon of informality in relation to colonialism, for example Home, 1983 argues that quite often the physical separation of colonial from traditional urban forms creates “twin cities” in symbiotic relationship. Similarly House, 1984 argues that the formal and informal sectors are generally thought 17 to be symbiotic, with the vitality of the informal sector depending upon the wages and demand generated by the formal sector. This dualism could be seen in the British colonial administrative formula of indirect rule, through which parallel governmental structures (“native” and “European”) co-existed (Myers, 2003:5). This system of governance further reinforced the informal/formal dichotomy of spatial and social segregation. The emergence of informalities can therefore be traced to the beginning of colonialism, when dual systems of urban processes were institutionalised i.e. the “European” and the “Native” (Myers, 2003; Mitchell, 1991). These dualities gave birth to one of the major realities in third world cities today; the informal/formal divide. This can be attributed to the Eurocentric view of order, propagated in the colonial period, where for there to be an inside there must be an outside – the twin phenomenon. That is why early Europeans experienced Egypt differently; Flaubert experiences Cairo as a visual turmoil. At first it is indescribable, except as disorder. What can he write about the place? That it is a chaos of colour and detail, which refuses to compose itself as a picture (Mitchell, 1991:21). This early pre-conception led to the segregated colonial city that encouraged the phenomenon of informality i.e. formal/informal, rich/poor, European/African, inside/outside etc (Mitchell, 1991). Space as a phenomenon is intrinsically neutral, however, space acquires a given meaning or category according to specific circumstances. Space can be informal, social, economic, Euclidean, capitalist, colonial etc, or even urban depending on one’s concept of urbanity. In general spatial categories are social constructs. In discussing informal urbanisation, space plays a central role, since the focus of the discussion is on the production and consumption of urban space, and whether it is formal or informal (Mitchell, 1991; Myers, 2003). Informality as a residential and professional social category was invented as soon as Western capitalism entered Africa. This happened during the early years of colonisation, the period of establishing a European presence in Africa. It was also a period of creating a political order that inscribed in the social world a new conception of space, new forms of personhood, and a new means of manufacturing the experience of the real (Mitchell, 1991). 18 The early colonialists manipulated space, by applying the principles of enframing, in order to exploit, legitimise colonial rule and dominate the colonised. These colonialists were pre-occupied with an attempt to create order in all spheres of life in the new colonies, and spatial order became a major pre-occupation. Where there was an existing settlement, like in Egypt, the new spatial order became the formal while the old order became the informal (Berman, 1990; Home, 1997). Similarly, in Uganda the British established a formal municipality while the local Ganda capital (the Kibuga) remained informal (Gutkind, 1960; Sanya, 2002), space was categorised according to who controlled it. Lefebvre, 1976 posits that capitalism has survived in the 20th century by one and only one means ‘by occupying space, by producing space’. In manipulating space, the principle of spatial segregation played a major role in the colonial logic. In colonial Zanzibar for example space was divided among the European colonial elite, the Indian traders and the African urban majority. Spatial segregation was carried out across the entire colonial Africa, culminating in the apartheid policies of Boer South Africa. Major changes took place in many countries at independence; however, in matters to do with urban planning, the post-colonial regimes chose continuity rather than change. The colonial obsession with spatial order as an ideological tool and means of civil control: - segmentation of the city, containerised notions of inside and outside plus central spaces of observation and surveillance, persisted after independence (Myers, 2003). These spatial orders however, virtually ignored the every-day spatial life-world of the urban majority. These urban majority, resort to re-framing these colonial frameworks through their limited power (uwezo), local customary practices (desturi) and through faith (imani). Very often the results of this spatial re-framing by the urban majority are informal settlements. The above colonial notions of urbanity in developing countries came to be regarded as the traditional practices in the cities of these countries. This assumption led to the institutionalisation of the formal/informal dichotomy, where formal processes were seen as those with Western roots, while informal processes were those based on local/indigenous practices. This divide of the formal/informal is at the core of this thesis. 19 What now follows is the discourse rooted in the informal urban process. Evidence will be adduced to show that the phenomenon of informality has had a major influence on the production of cities of developing countries. This has generated a different city model from the Western model. The Discourse Rooted in the Informal Urban Process Evolution of the Concept of Informality Studies on the informal sector, started as an economic concept, and then were partially transformed into social and spatial concepts, especially in francophone literature (Coquery-Vodrovitch, 1991). Earlier on, in the 19th century, small towns in the African savannah were the locus of urban social stratification with distinctions between the rich and the poor. The poor had no other way to survive but by dependency and slavery or perhaps by individual techniques of independent survival possible in cities (Vidrovitch, 1991:59). Pre-colonial African societies had pre-mercantile trade based on a barter system, where most relationships between the trading parties were informal in nature (Amin, 1976). Some of these practices persisted during the colonial period, as they were already embedded in the pre-colonial social economy. Therefore the informal sector is not a new reality, but as a residential and professional social category, it was produced as soon as Western capitalism entered Africa. (Cooper, 1987; Vidrovitch, 1991). The earliest references to the phenomenon of informal urbanisation appear in the work of John F. C. Turner and Charles Abrams (Abrams 1964, 1966; Turner 1968). But the first time the term informal is used with regard to urban policy is with the International Labour Office (ILO) Employment Mission to Kenya in 1972. According to the ILO definition the informal sector is constituted by those activities characterised by ease of entry, reliance on indigenous resources, family ownership and resources, skills acquired outside the formal education system, labour intensive, easily adapted technology, unregulated and outside fully competitive markets (ILO, 1972). In an attempt to solving the proliferation of informality in Third World Cities, Turner advocated for the integration of squatters in formal urban structures. The Turner 20 paradigm which was based on autonomy and subsidiarity was instrumental in the development of later day “site and services” projects. Turner would later disagree with the direction that the understanding of his research was taking. His concern, “squatters are part of the solution not the problem” and his fundamental point was that; The intrinsic dis-economies and social dysfunctions of centrally administered personal services lead to the inevitable failure of commercially or institutionally centralised housing (Turner, 1976:257). Turner further brought to light the issues of autonomy and heteronomy in building environments, by asking fundamental questions with regard to urbanisation. Whose participation, in whose decisions and whose actions? (Turner, 1976:139). In development economics, it is only recently that the importance of cities for economic development has been recognised. In fact, multilateral and bilateral agencies only slowly formulated strategies for urban development, but unauthorised settlements were either ignored or demolished, and informal income generation was considered to be a passing phenomenon, linked to high rural-urban migration. However such policies that advocated for the demolition of informal settlements/housing, did not increase the housing stock of the cities in question. It is on this basis that Turner argued that informality is not the problem, but part of the solution to the housing question. Researchers during the 1970s and 80s tended to view the informal sector as a “bulk”. Informality was applied indiscriminately to construction, economic, social and political activities. Lisa Peattie has argued recently that the term “informal sector”, though very helpful in many instances, had become a sort of “semantic blanket over a variety of enterprises sharing the attributes of being off the map” (Peattie, 1996). It has reached its limitations in offering convincing explanations and informing public policies. In addition, most of the literature regarding informal urbanisation has focused on the issue of housing, which seems natural if one takes into account the rhetorical and ideological value of housing. Both in academic research and in policy making, housing has been the favourite subject of choice. The work of Turner in Peru, extremely influential in academic writing, planning, and among development agencies, became the paradigm for institutional housing policies in most of the developing world. 21 Other authors dealing with informality use the term informal settlements to “emphasise the economic connotations of the modality of housing in contrast with the formal market” even though arguing that informality refers to settlements existing outside the institutional systems and formal markets, rather than from being spontaneous (Alexander 1986:53 in Castillo, 2000:23). Schteingart, 1990:110 in Castillo, 2000 defined informal housing as a form of housing production that does not meet legal guidelines with regard to the mode of land appropriation and construction regulations being undertaken without official government permission. In addition, builders in the informal sector lack financial aid, and they use indigenous building techniques. For Portes, Castells and Benton the central feature of the informal (economy) is the fact that its activities are unregulated by the institutions of society, in a legal and social environment in which similar activities are regulated. In addition to the above, initial expectations that the informal sector would soon be absorbed into the formal have given way, at least through the decade of the 1990s, and that informality seems to be spreading (Lubell et al. 1991). Scholars recognised that informal development was no longer “an illegitimate child born out of the process of rapid urbanisation”, (Ward, 1982:276), especially population increase and migration. The debates for and against informal urbanisation are for the most part non-conclusive. For Ward, as well as others (Burgess, 1982; Harms, 1982), the state was giving up its responsibilities to society by favouring self-help and not developing stronger housing policies. In 1989, Castells and Portes argued that the informal economy was a structural feature of all advanced economies, the boundaries of which were adjusted with political and economic shifts. They defined the informal economy not as an activity per se, but as income-generating activities that are not regulated in the context in which they are legally required to be. Castells and Portes, 1989:12 characterised informality as having one central feature of extra legality. Additionally, according to ILO usage, the informal sector is composed of unenumerated self-employed, mainly providing a livelihood for new entrants into the cities. In recent times, the phenomenon of informality is being reconsidered, with a view of taking advantage of some of its positive attributes. These attempts will try to overcome 22 the bureaucrats’ tendency of constructing a model of the social field in which they want to intervene; this model is thus the basis for a formal understanding of a social field. This formal understanding necessarily cuts away large chunks of the social field, highlighting only those aspects that are open to enumeration and manipulation (Hansen and Vaa, 2004:46). According to Nustad 2004, the term “informal” was coined as a term for acts and processes that escaped certain economic models. Thus, ‘informality’ is not itself a characteristic of an activity; it only signifies that it has been left out by a definition that is ‘formal’. But, as the history of this concept clearly demonstrates, in naming there lies a peril: “the informal”, instead of denoting the flux of social practices, was instead encompassed by formal models as a residual category for everything which escaped the conceptual grid of administrators and academics. Nustad further posits that, despite this fate, the informal/formal dichotomy can act as a useful tool for analysing attempts by bureaucrats at ordering the world according to their models and people’s responses to these attempts (Nustad in Hansen and Vaa, 2004: 45-61). Nustad, 2004 further posits that: Informality is in the eyes of the beholder. One of the original merits of Hart’s work was to point out that “the informal” can not be equated with the irregular, irrational, unpredictable, unstable and invisible. The informal denotes phenomena and processes that escape certain definitions of reality (Nustad in Hansen and Vaa, 2004:58). The people, whose strategies and acts are denoted as informal, would of course believe that they lived within social forms which help them to manage their lives, in other words informality is a subjective social construct. Finally, it should be noted that although colonialism perpetuated informal urbanisation, the informal economy is a near universal phenomenon, present in countries and regions at very different levels of economic development and not confined to a set of survival activities performed by destitute people on the margins of society (Hansen and Vaa (Ed), 2004:11). The phenomenon of informality is gradually becoming a central theme of the urbanisation discourse, as exemplified by many publications, particularly those by UNCHS on the urbanising/globalising world. This general debate and attitude towards 23 this phenomenon of informality and its relation to the urban process, by bureaucrats and many scholars has been ambivalent. This ambivalence has led to other debates on informality, which I now address. Other Debates on Informality The Urban Informal Sector (UIS) debate which was aspatial fundamentally, gained prominence in the early 1970s, as evidenced by the large amount of literature on this phenomenon. This debate has generally focused on the social/political economy of cities or countries, where issues to do with governance, poverty, migration, human rights, gender equity, urban management etc., have been addressed (Rakodi, 1997; Fernandes and Varley, 1998; Simone, 2002). With regard to human settlements, the issues raised have been to do with informal settlement upgrading, squatting, energy use and environmental sustainability among others (UNCHS, 2003, 2001, 1996; Syagga, 2002). Coquery-Vidrovitch posits that there is an ideological significance for labelling this phenomenon as informal. It underlines the Western tendency to put out-of-bounds all economic activities which could not be strictly labelled as those within the market or state systems. It is not by chance that the concept appeared at the very beginning of the 1970s, at the moment when industrialisation and modernisation (read Westernisation) were still offered as the unique hope for development (Coquery-Vidrovitch, 1991:60). On the example of Mombasa, Cooper illustrates the anteriority of this recently discovered informal sector, which long existed and was known to the British “as living off one’s wits” (Cooper, 1987:181). So what is the significance of the present anteriority? More recently, Castillo, 2000 posited that; the term informal when categorizing urbanisation, has sometimes been used synonymously with other terms such as; irregular, illegal, uncontrolled, unauthorized, unplanned, self-generated, marginal, shanty, spontaneous or even self-help. Each of these terms while related, and most of the time referring to the same phenomenon, seeks to emphasize one aspect of the subject of research. 24 It is important to acknowledge that this urban condition cannot be understood one-dimensionally, and that each term carries a bias, ideological, disciplinary etc (Castillo, 2000:22). The economic perspective in the informality debate gained prominence during the modernists’ period, although from time immemorial economics has always played a significant role in the urban process. Urbanisation is perhaps the only enduring trend in human history. The high rate of urbanisation that is occurring throughout the developing world parallels that which occurred in England and some other European countries during their industrial revolutions in the 18th and 19th centuries. What is different now is that urbanisation is not being accompanied by adequate economic growth in many developing countries; this scenario creates a situation of urbanisation of poverty (UNCHS, 2003:25). In addition, cities are complex systems, and as societies urbanise, their economies become increasingly differentiated. Their organisation increasingly revolves around specialised activities in the production, consumption and trade of goods and services. The appearance of informal settlements was not only due to population pressure from immigrant proletariat that began thronging the capitals of Europe, but was also due to the depersonalisation of people and commodification of space that occurred during the early days of capitalism (Vidrovitch, 1991, Harvey, 1986, Lefebvre, 1979).4 In recent years much of the economic and political environment in which globalisation has accelerated has been instituted under the guiding hand of a major paradigm: neoliberalism; which is associated with the retreat of the national state, liberalisation of trade, markets and financial systems and privatisation of urban services (UNCHS, 2003:2). In the face of shrinking formal urban employment opportunities, global, and national policies as much as anything else, have led to the rapid expansion of the informal sector in cities. The Stretched capacity of most urban economies in developing countries is unable to meet more than a fraction of the population’s needs, so that the informal sector is providing most of the new employment and housing in environments that have come to be known as informal settlements or slums, where more than half the 4 This commoditisation of space was to have a major impact on the urban process of Nairobi, as will be shown in chapter 3, 4 and 5. 25 population in many cities and towns of the developing countries are currently living and working (UNCHS, 2003:5) Informal economic enterprises- those defined as small-scale, mostly family operated or individual activities that are not legally registered and usually do not provide their workers with social security or legal protection- absorb at least half the work force in many large African cities. For sub-Sahara Africa, the informal economy engages 63% of the total urban labour force (Rakodi, 1997). On the other hand, the accumulation of capital and often ostentatious Western lifestyles of the national elites and bourgeoisies are built on exploitation, very similar to what the colonialists did. The majority of the residents within these third world cities are marginalised, and have very little stake in this globalising materialistic culture. Informal settlements and urban poverty are not just a manifestation of population expansion and demographic change, or even of the vast impersonal forces of globalisation. Informal settlements must be seen as the result of a failure of housing policies, laws and delivery systems, as well as the failure of national and urban policies. The urban poor are trapped in an informal and “illegal” world – in settlements that are not reflected on maps, where waste is not collected, where taxes are not paid and where public services are not provided (UNCHS, 2003:6), And as Chabal and Daloz would put it, where there is a general instrumentalisation of disorder. Before the 1980s post-modern paradigm shifts, theories of spatial distribution, residential differentiation and ecological succession had been developed by urban researchers. These as discussed earlier, by and large can be traced to the “Chicago School” of the 1920s and 1930s, which sought to explain market-driven cities, where land use is determined by economic competition. These theories are less applicable to many of the cities of the developing world that are still undergoing transitions from more traditional exchange and land tenure regimes (UNCHS, 2003:17; Syagga, 2002).5 The 1980s neo-liberal theories have also impacted negatively on many third world urban residents, their emphasis on economics and market forces has not worked in situations of high levels of inequality as market forces are generally not pro-poor. The growth in the global labour force has 5 These transitions are similar to the transitions that took place in Europe and North America on the advent of the industrial/capitalist society. 26 imposed enormous strains on urban settings, especially on employment and housing, and as the formal sector has failed to meet such demands, the informal sector has taken up the slack, in other words informality has occurred by default. From an economic perspective, ‘informality’ suggests a different way from the norm, one which breaches formal conventions and is not acceptable in formal circles – one which is inferior, irregular and, at least somewhat undesirable. Informality involves internal organization with a relatively flexible and informal hierarchy of work and roles. It displays little or no division between labour and capital as factors of production (UNCHS, 2003:100). Similarly, some Marxist oriented writers, have, argued that ‘informal’ was a bourgeois term that covered up class relations. After initially embracing the concept, a number of social scientists began arguing that the formal/informal dichotomy was not really helpful at all: actual cases of informal economy activity proved to be closely tied to the formal economy; and this undermined, it was argued the usefulness of maintaining the dichotomy (Skar, 1985). Coquery-Vidrovitch also argues that informality is rooted in history, and concepts such as tradition or the informal sector are dead-ends. African cultural processes and African problems of employment are neither traditional nor informal. In a way they are commonplace and must be studied as both universal and specific phenomenon (Coquery-Vidrovitch, 1991:74). The foregoing debates have highlighted how the phenomenon of informality has been addressed basically from a Eurocentric/Western perspective. In order to enrich the understanding of this phenomenon, I attempt to address it through third world lenses. What now follows is the third world perspective of urbanity in the context of informality. Re-conceptualising Urbanity in Developing Countries In order to discuss the present day binaries of the urban process in third world cities, a myriad of terms have been invented e.g. self-help, illegal, informal, spontaneous, unplanned, unauthorized etc. This categorisation in effect, continues to marginalise and exclude from mainstream urbanity a large percentage of the processes producing third world urbanisms today. (Rakodi, 1997; NISCC, 1997). These approaches however tend to treat these urban processes as homogeneous, yet they are diverse and heterogeneous 27 and need not be treated as one category. The urban processes which have been lumped together have in general applied to the urban poor, what however is currently taking place in most Third World cities, are processes that cut across socio-economic classes; the poor, the not-so-poor and the well to do.6 Very often these processes result from the interplay of both the formal and informal processes with the resultant hybrid urbanisms being what I want to refer to as “Diverse Urbanisms”. Space plays a central role in diverse urbanisms, as space is the object that is manipulated through both formal and informal processes to create these urbanisms. Empirical evidence has shown that these urbanisms are not homogeneous and there is a need to sketch the actual account of these processes and develop a more sophisticated, accurate, and politically/technically useful understanding of these processes. This may be a tall order, but a general theory of “diverse urbanisms” which results from “diverse informalities”, is what is required if we have to comprehend third world urbanity It is not possible to develop an integrated city, if the majority of the population and economic practices are continually excluded from official policies and processes. Publications such as UNCHS’ “Challenge of Slums”; Fernandes and Varley’s “Illegal Cities” among others miss the point. This is because they try to lump together all the informal third world urbanisms into a specific category i.e. slums or illegal cities. I wish to point out that names have their own biases, and at the same time acknowledge that term like informal/diverse gives a positive face to these settlements while terms like slums/ illegal actually condemn them. Moreover, these settlements have come about due to poverty, exclusion, unaffordability, weak local authorities etc.; these are some of the issues the relevant authorities never highlight/address. That is why “Reconsidering Informality” by Hansen and Vaa, 2004 begins to question the validity of these general categorisations. In order to generate sustainable urbanisms in many third world cities, it will be necessary to bring the ‘urban majority’ on board and discard the current elitist agenda. From a historical perspective, older European cities grew in an environment where market norms and feudal landholding systems had been well established in the Middle Ages, and dwellings could be readily traded by owners or landlords for alternative uses 6 See Study Model Fig.2.1 28 (Friedman, 1988). The early industrial cities grew during a time when most work was centrally located and people walked, then later expanded to suburbs along rail corridors, filling between these corridors as personal motor transport became universally available (UNCHS, 2003). However, the situation of cities that have emerged as substantial centres in the developing world during the past 50 years is often very different from that of a succession of land uses described by the Chicago School (UNCHS, 2003:17). In any case, did these third world cities industrialise? The Chicago School theories might have been applicable in the first half of the 20th century in the West; it is unlikely that they can work today in Third World situations. Planning within a political system of monopolistic power serves to reinforce hegemony rather than operate as regulatory framework; this makes the issue of informality rather problematic, since informality as an issue to be addressed by planning is a fairly recent phenomenon, as it started being addressed at the beginning of the 1970s, as discussed earlier. Regularisation and security of tenure dominated the policy agenda of the late 1970s and 1980s; regularisation however, is just a minor step in incorporating informal settlements to the city (Castillo, 2000). Most research has shown that; regularisation is closely tied to political patronage, consensus building and party favours. Many settlements can exist for years without getting services, if residents are unable to organise and use political pressure to satisfy basic services such as water, sewage and electricity. From the 1990s to date, the neo-liberal policy of enablement and liberalisation has been the dominant policy in most developing countries.7 In trying to understand “third world urbanity” we need to refocus on practices (social, economic, architectural and urban), and the forms (physical, spatial) that a group of actors/ stakeholders (dwellers, developers, planners, land owners and the state), undertake not only to obtain access to land and housing, but to also satisfy their needs to engage in urban life (Castillo, 2000:29). To call third world urbanity “diverse urbanisms” as opposed to informal urbanisation is to discard the stigma of informality, in addition to acknowledging that this process involves much more than the construction of dwellings. It involves the production of public and private space, and creating strategies 7 Policies towards informal urbanisation are addressed later in this chapter. 29 for satisfying all the other urban necessities such as health, education, transportation and access to jobs (Rakodi, 1997; Simone, 2002). Very often politicians determine the fate of most informal settlements. They may declare some settlements as upgrading areas, and therefore officially recognised as part of the formal urban fabric, which is tantamount to urbanisation by decree. On the other hand the regularisation process appears to be a conciliatory gesture rather than an application of the law. From the government’s initial tolerance of illegal subdivisions and sales, to the painless regularisation process, the authorities recognise that informal developers fill in a social void. Not only is urban law negotiated among stake holders, but even worse, urbanity is granted by “decree”. This is probably one of the most unfortunate costs of informal urbanisation for settlers and society. Residents are forced to invest more in political actions and lobbying than in productive activities that would improve their economic and social conditions (Castillo, 2000:38). I use the term “Diverse Informalities”, in discussing the urban process in developing countries. These informalities generate diverse urbanisms, and represent a new model of urbanity both in the processes and in the forms, as Castillo posits in urbanisms of the informal; The new model questions the two dominant approaches to city planning; those guided by civic, visual or iconographic order and those where planning is a result of rational quantitative decisions (Castillo, 2000:141). Diverse informalities will emphasise the spatial dimension of informality, as opposed to the models guided by legal, economic, social or anthropological distinctions. Most concepts used to describe informality such as illegal, irregular, self-help etc., are socially constructed (and can, and tend to disappear over time), space, as a condition of diverse informalities, remains over time. It is precisely because of this permanence that a spatial framework of the phenomenon of informality can be more accurate and instrumental. Diverse informalities will place the issue of architecture and urban design at the centre of the discussion of informal urban processes. The spatial dimension has often been ignored in the discussion of informality. Simone, 2002 in re-thinking urban sustainability in a time of uncertainty, explores how 30 informality can function sustainably in an urban context. Simone observes that; informal urban practices are characterised by tactical and incremental decisions, by a complex interaction among players, and a distinct set of spatial strategies that produce a progressive urban space and a reconfiguration of its hierarchies. This observation is further illustrated in chapter four Fig.4.7, where space is configured and evolves from a survivalist category to a kiosk-a primary category of informality. Suspending judgement on the quality of the urban environment resulting from informal processes, should produce a better understanding and possibilities of creating better policies for more effective programmes. This does not mean accepting the fiction that because it exists, informal urbanisation is optimal. On the contrary, to recognise and describe the processes and the sort of space produced through this phenomenon is a first stage in reducing its enormous social, developmental and environmental costs. To call the phenomenon “diverse informalities” as opposed to informal housing is to emphasise that the production of urban space by the settlers, developers and the state, is a totality beyond the construction of private buildings. It involves the production of the public space, and the strategies for satisfying all their urban necessities such as health, education, transportation and access to jobs (Castillo, 2000:30). Some of these strategies are also highlighted by Castells, 1983:212 who posits that when squatters refuse to live in high-rise buildings, it is not only because of their essential traditionalism- they need to raise poultry and cultivate vegetables as a basic element of their subsistence, therefore they cannot afford the luxury of living above ground. In the current era of globalisation, the forces of globalisation have in general impacted negatively on most Third World Cities, the implementation of structural adjustment programmes created the loss of public sector jobs, without creating private sector jobs. At the same time, economic and cultural differences between city and rural areas have become increasingly blurred, because of this trend which has recently led to a proliferation of urban agriculture as a survivalist strategy. The privatisation process has favoured multinational corporations which have increasingly marginalised local enterprises. Local products have been unable to compete for opportunities generated by global markets. 31 All these factors have caused a further deterioration of the living standards in Third World Cities including the built environment. Globalisation has not created a homogeneous global society, but has benefited the ruling classes and a few business elites of the Third World (Rakodi, 1997). Africa in particular, has been integrated into the world trade system on unfavourable terms and has become dependent on international assistance. Although Coke, McDonald’s and even Toyotas in varying states of decrepitude are now common commodities from Greenland to Mt. Kilimanjaro, and are having an impact on lifestyles, we can not assume that this is necessarily evidence of social and cultural convergence in a unidirectional linear sense with predetermined or universally predictable outcome (Rakodi, 1997:76). On the other hand De Soto, 2001:219 argues that; Capitalisation is in crisis outside the West not because international globalisation is failing, but because developing and ex-communist nations have been unable to “globalise” capital within their own countries. Similarly, Simone, 2002, wonders whether mobilising informal networks and processes within African cities can serve as a platform for more proficient engagements of global urbanisation processes and for building a more equitable and sustainable city. Globalisation and current communication technology is here to stay; the onus is on Third World cities to exploit their abundant human resources available in these cities. Because of these dynamics; Increasing numbers of Africans are situated in what could be called “half-built” environments- i.e. under-developed, over-used, and fragmented and often makeshift urban infrastructures- but whose inefficiencies themselves induce the cultivation of new health and social problems and the “urbanisation” of existing ones (Simone, 2003:21) The concept of informality has been used to legitimise certain legal and governance practices in many African countries; however, in general, informality and legality have not enjoyed a cordial relationship. Very often informal practices seen from a legal perspective have been branded “illegal”. During the colonial and the immediate postcolonial eras, the management of towns and cities followed what have been described as 32 the “Anglophone” and “Francophone” models of government. The image of towns as places of “European settlement” prevailed and the patterns and processes of governance reflected this (Rakodi (ed), 1997:541). Cities in developing countries are facing different challenges from those in the West. Developing and ex-communist countries are facing (albeit in much more dramatic proportions) the similar challenges the advanced nations dealt with between the 18th century and the Second World War. Many cities are faced with massive informality and are unable to formally provide urban goods and services. In fact; Massive extra legality is not a new phenomenon. It is always what happens when governments fail to make the law coincide with the way people live and work (De Soto, 2001:96). In Paris for example, the legal battle between tailors and second-hand clothes dealers (informal traders) went on for more than three hundred years, it was stopped only by the French Revolution. De Soto, 2001 who examines informal urbanisation through the prism of capital, argues that nearly every developing and former communist nation has a formal property system; the problem is that most citizens cannot gain access to it. Their only alternative is to retreat with their assets into the extralegal (informal) sector where they can live and do business – but without ever being able to convert their assets into capital. To a large extent, they apply practices which were embedded in their pre-capitalist social economies (Amin, 1976; Ayittey, 1991). In most Western European countries, law began adapting to the needs of common people, including their expectations about property rights, during the 19th and early 20th centuries. In fact the past of Europe strongly resembles the present of developing and former communist countries. The history of the adoption of occupancy laws in the United States of America is the history of the rise of extralegals as a political force. The pre-emptive concept helped the American legal system to accommodate the informal (extralegal) land practices during the 1830s, through the adoption of the Pre-emption Act of 1830. It can rightly be said that extralegal groups played an important role in defining property rights in the United States and added value to the land. American property changed from being a means of preserving an old economic order to become, instead, a powerful tool for creating a new one (De Soto, 2001:158) 33 There has been a general assumption that informality is cheap, contrary to this popular wisdom, operating in the underground is hardly cost-free. Extralegal businesses are taxed by the lack of good property law and continually having to hide operations from the authorities. Extralegal social contracts rely on a combination of customs and ad hoc improvisations of rules selectively borrowed from the official legal system. The American legal system obtained its energy because it built on the experience of grassroots Americans and the extralegal arrangements they created, while rejecting those English common law doctrines that had little relevance to problems unique to the United States (De Soto, 2001). African and ex-communist countries can borrow a leaf from the above American experience in main streaming their extralegal sectors. The reason why extralegal arrangements in many third world countries have become widespread in the last forty years is because formal law has not been able to accommodate rapidly evolving extralegal agreements. Quite often, legal reforms are bureaucratic and slow, and if they do happen, they will normally have been overtaken by events. In real estate for example, extralegal social contracts originate not only from outright squatting, but also from deficient housing and urban or agrarian reform programmes, and the illegal purchase or lease of land for dwelling and industrial purposes (De Soto, 2001:187). In many urban areas, extralegal buildings and businesses evolve over time until they are barely distinguishable from property that is perfectly legal. If cities in the developing world have to attain some measure of integrated development, they need to accommodate informal processes in the formal. De Soto posits that: By bringing the extralegal sector inside the official law, it is possible to open up the opportunity for massive housing programmes that will provide the poor with homes that are not only better built but much cheaper than what they themselves have been building in the extralegal sector (De Soto, 2001:205). Where as I may agree to some extent with the above view, it may apply, mostly to middle income earners, I doubt that it will apply to the very low income groups. These very low income groups will still require massive subsidies from the state, if they have to operate within mainstream law. 34 Creating a property system that is accessible to all is primarily a political job, because it has to be kept on track by people who understand that the final goal of a property system is not drafting elegant statutes, “connecting shiny computers or printing multicoloured maps, but putting capital in the hands of the whole nation” (De Soto, 2001:218). Evidence in Nairobi for example shows that there is no political will to change the status quo in matters to do with property and land reforms. The unprocedural allocation of land and the lack of checks and balances in the system, benefits government officials, the same officials who are supposed to institute meaningful property reforms (Syagga, 2002:79) Extralegal arrangements are the dominant mode of carrying out business in the absence of affordable legal means. These arrangements however have a; disadvantage in that they are not integrated into the formal property system and as a result are not fungible and adaptable to most transactions; they are not connected into financial and investment circuits; and their members are not accountable to authorities outside their own social contract (De Soto, 2001:90). It should however be acknowledged that extra legality is rarely anti social in intent. The “crimes” extralegals commit are designed to achieve such ordinary goals as building a house, providing a service or developing a business. Chabal and Daloz, 1999 address the phenomenon of informality in developing countries by exploring three fundamental issues: - The informalisation of politics, the retraditionalisation of society and the production of economic failure. They argue that during the colonial period for example, justice was more frequently rendered by the colonial administrator than by a magistrate sitting in a court of law. As a result, the ideal type of the (Weberian) bureaucratic state essentially remained a myth of the colonial mission and there was never much chance that it would survive at independence (Chabal and Daloz, 1999:12). The post-colonial period in many African countries has been characterised by informality at all levels of political organization, where informalisation is a condition for the reproduction of political power. It is the means for mediating pressures exerted from external institutions and forces and those coming from inside societies (Simone, 2002). In this regard, it is essential to understand that the foundations of political accountability in 35 Africa are both collective and extra-institutional (informal): They rest on the particularistic links between Big Men, or patrons, and their constituent communities. The African informal political order is a system grounded in a reciprocal type of interdependence between leaders, courtiers and the populace. And is a system that works, however imperfectly, to maintain social bonds between those at the top and bottom of society (Chabal and Daloz, 1999:44). What happened in the post-colonial period was the Africanisation of politics, that is, the adjustment of imported political models to the historical, sociological and cultural realities of Africa. This is still going on today: the so-called democratic transitions are being reinterpreted locally. In Africa, it is expected that politics will lead to personal enrichment just as it is expected that wealth will have direct influence on political matters. Rich men are powerful. Powerful men are rich. Wealth and power are inextricably linked (Chabal and Daloz, 1999:52). These collective and informal accountability systems and the Africanisation of policies, have a major impact on the urban process. Land transactions, tender procedures and award of contracts plus many other national business transactions are carried out informally and shrouded in secrecy. This leads to the inability of the formal development control mechanisms of having any meaningful impact on the urban process. The overlap between the formal and the informal as well as intense rivalry between patrons creates an ideal framework for the spread of criminal activities. Informalisation is nothing other than the day-to-day instrumentisation of what is a shifting and ill-defined political realm. The informal political system functions in the here and now, not for the sake of a hypothetical tomorrow. It can only work if it meets its obligations continuously. In other words its legitimacy rests with its immediate achievements, not with its longterm ambitions. It does not allow for delayed reward or achievement-much less for long term investment. That is partly why, although many African countries have been independent for more than 40years, very few have attained any meaningful economic growth, as the short-term approach to issues based on the need for immediate results, has compromised long term strategies for problem solving. 36 The informal political order in Africa can only change when ordinary African men and women have cause to reject the logic of personalised politics, seriously question the legitimacy of the present political instrumentation of disorder and struggle for new forms of political accountability (Chabal and Daloz, 1999:162). Evidence in Nairobi shows that; the government rarely addresses the issue of informality. Quite often, government resources are used for the development of middle and high income housing in which government operatives have direct interest. Governance and management are much more problematic in urban areas, as Rakodi, 1997 posits; urban management systems in most African cities are generally unable to keep pace with infrastructure needs and, in some cases have all but collapsed. This has created fertile ground for the informal procurement of these services, or improvisation of the same. 8 As discussed earlier, informality is not homogeneous, as there are various layers of informalisation ranging from enterprises that simply operate without licences, pay no tax, or occupy a particular site without permission to major corruption and crime. Simone, 2002 also identified “the informal dimension” as the peculiar characteristic of African urban reality, it is this dimension that, new forms of social interaction are developing and consolidating. He further argues that these new forms demand to be interpreted with innovative conceptual tools in order to be able to re-think the models of urban development and the institutional typologies necessary to ensure a sustainable future to African cities. It is estimated that roughly 75% of basic needs are provided informally in the majority of African cities, and that processes of informalisation are expanding across discrete sectors and domains of urban life (Simone, 2002). Mabogunje, 1994 observed that; despite concerted efforts at municipal restructuring in Nigeria, and institution-building that have taken place over the last decade or so, many processes of city politics and administration have become increasingly informalised. Many formal institutions now exist simply as a context in which a wide range of informal business activity can be pursued. Thus institutions loose the capacity they might have had to facilitate a shared public interest. Simone, 2002 asks; 8 See the Matatu mode of public transport discussed in chapter 3. 37 Can mobilizing informal networks and processes within African cities serve as a platform for more proficient engagements of global urbanization processes and for building a more equitable sustainable city?(Simone, 2002). It should also be noted that, informalisation thrives particularly in weak states, where the privatisation of violence as a way to secure new political alliances means that the regime claiming state power has less need to secure uniform control over the territory of the state.9 The control of key resources, usually highly sectorised and geographically specific (like diamonds, gold etc), becomes more important than uniform administrative control. Thus, the conventional bureaucratic instruments of control, i.e., armies, public policies, regulatory systems, social welfare, are less reliable as instruments of regime control. This is especially the case in conditions where debt conditionality is enormous, nationallybased patronage networks are fractured and the public sector has been drastically reduced (Simone, 2002). In their 1998, publication “Illegal Cities” Fernandes and Varley explore the role of law, and illegality in the process of urban change in developing countries. They argue that the land use patterns, the relationship between legal and illegal favours the rich, the legal and institutional frameworks of these countries are often elitist and exclusionary. They further assert that the main urban challenge is indeed the development of legitimacy in urban governance (Fernandes and Varley, 1998). In some cities illegal settlements provide accommodation for over half the urban population. In this respect one is led to question the status of such settlements. The illegal city should be accommodated within the legal city if reality on the ground is to be reflected in law, because the credibility of the law will be seriously undermined if the majority of the citizens or residents are classed as illegal (Mitullah and Kibwana in Fernandes and Varley, 1998:191). Mitullah and Kibwana further posit that illegality and legality can be conceptualised purely on professional lines: the cities which the poor build and in which they live and work are different from and unrelated to what the city authorities want built. Similarly, too many countries still approach issues of land management in terms of rigid notions of 9 This is a condition akin to the current state of affairs in the Democratic Republic of Congo. 38 legality and illegality, McAuslan, 1994:582, argues that concepts of legality and illegality obfuscate rather than illuminate. Addressing some governance issues in Maseru, Leduka, 2004 argues that many people/groups in Maseru-Lesotho, are unable to legally access land for housing, resorting to non-compliance of the legal requirements. Non-compliance is a survival strategy, as well as a strategy to gain access to resources that would otherwise remain outside the reach of disadvantaged groups/individuals. Moreover, given their lack of input or voice in the formulation of policy, action by these groups is most effective if directed at policy implementation, where noncompliance becomes their only instrument of defeating or mitigating the negative effects of state policies (Leduka, in Hansen and Vaa, 2004:178). Leduka further argues that the disadvantaged individuals have no monopoly of the “weapons of the weak” as these are available for use by any group of individuals to resist state policies that might appear to threaten their interests. The illegal city, therefore, could be considered as an outcome of societal noncompliance and illustrates how the “weapons of the weak” might have enabled popular access to urban housing land by a majority of urban residents, irrespective of their socio-economic status (Leduka in Hansen and Vaa, 2004:178). Informal activities and practices may be illegal or extralegal but are not necessarily perceived as illegitimate by the actors concerned. It is likely that many urban residents consider what from the official standpoint is illegal or irregular as not only functioning but normal and legitimate practices. Most African countries inherited and have kept a legal framework for urban development that was designed to contain settlement rather than to deal with rapid growth. Even if blatantly repressive aspects such as pass laws were abolished at independence, zoning laws, building standards, and many other planning regulations have remained on the books in several countries. These regulations restrict the provision of housing affordable to the poor and the not-so-poor; the result is the emergence of unauthorized or illegal settlements (Hansen and Vaa, 2004:9). In recent years, state power is being de-institutionalised and decentralised under internal demands for democratisation and external pressure for economic liberalisation. Taken 39 together, factors such as central governments’ lack of resources, misappropriation and patronage are pushing a variety of initiatives on to civic associations and NGOs, fuelling the informalisation of services that the state is unable to provide. Jenkins in Hansen and Vaa (Ed), 2004 posits that the concept of formality is particularly problematic, because of its basis in legal and regulatory systems whose legitimacy for the majority of the urban population may be doubtful. The formal/informal dichotomy is too simplistic to capture the social, economic and political complexities of urban situations. In fact the urban processes taking place in most post-colonial cities are quite diverse, generating “Diverse Urbanisms”, which encompass both formal and informal practices. Evidence from Maputo shows that an alternative approach to the traditional formal/informal approach is possible, this approach is based on the concept of different forms of socio-economic exchange, reciprocity, redistribution and the market (Jenkins, in Hansen and Vaa, 2004). In other words the emphasis on legality and economics as the main variables in urban processes should be balanced with the social, cultural and political variables. It should also be appreciated that the inherited colonial legal system which was incomplete and contradictory has led to even more complexity in the definition of legality. In many countries the post-independence political and economic elite favoured the retention of existing complex legal systems which, while cumbersome, could be worked to their advantage due to their greater access to resources and power. The nature of state capacity also underpins this: the state is politically weak and its legal system has low administrative and technical capacity. This leads to bureaucratic groups also manipulating regulatory regimes to their comparative advantage. In addition to questioning the legitimacy of legal structures which effectively marginalise the majority, there is a growing literature on governance, state legitimacy and the relationship between state and civil society, which queries the legitimacy of regimes and social groups who draw benefits from the state (Hansen and Vaa, 2004). Very often the legal status of settlements and structures in matters to do with urban development is over emphasised. However, legality is not particularly valuable to the poor, many of the outcomes of legality are desirable, but can be achieved in different ways (Payne, 2002 in UNCHS, 2003). In fact, there are differences between legitimacy 40 and legality, and a number of tenure arrangements stop well short of formal titling while providing the desired benefits. Secure de facto tenure is what matters to the inhabitants first and foremost – with or without documents. It is the security from eviction that gives the house its main source of value (Angel, 2001 in UNCHS, 2003). Castillo argues that the division between formal and informal as seen through legal eyes is flawed on two counts: First; it assumes that implementation of the law is constant and effective. The weakness of the law affects the process of urbanisation at all stages of it. Second; assuming, incorrectly, that informal urbanisation disregards the law, and operates in spite of it, not because of it. Informal urbanisation does not regard legal norms as irrelevant; on the contrary, the law is a real and substantive factor in the formation and consolidation of informal settlements, in other words extralegality operates because of legality. Fortunately, recent legal research has focused on the idea that property law does not embrace a single conception of property rights, that there are distinct ‘levels of illegality’, and that the state has ceased to be the sole judge and regulator of the legal and the legitimate (Castillo, 2000). This view brings into focus the ‘diverse’ or “hybrid” urbanisation processes taking place in most Third World cities. Legality and for that matter illegality are socially constructed terms, making it difficult to have a clear-cut application of legality and illegality. Castillo identifies four misconceptions of informal urbanisation, which have to be addressed critically in the understanding of these urban processes. The four are: Informal urbanisation is unplanned urbanism; informal urbanisation is only self-built housing; informal urbanisation will ultimately disappear and informal urbanisation is not a legitimate form of urbanity. Empirical evidence shows that these misconceptions have been proven wrong as most informal processes are generally planned, seen from the perspective of the developer or activity manager. Informal urbanisation involves more than self-help building and has not been able to disappear but has grown over time. The legitimacy of informal urbanity is contestable since legitimacy is socially constructed and will vary from time to time, depending on circumstances, in any case as was shown earlier the legitimacy of formal urbanity is also contestable. However if order 41 has to be maintained, some laws must remain inviolate so that there is a certain level of continuity over long periods of time. The above discussion on the condition of cities in developing countries shows that the current ruling classes have been unable to maintain the model of city left behind by the colonial powers. The colonial system of ignoring the presence of local/indigenous people in urban areas is no longer tenable and cannot be enforced. This has exacerbated the proliferation of informal urban processes to the extent that many processes that were originally formal now operate informally. It is this state of affairs that requires the reconceptualisation of urbanity in developing countries, with a view to generating a viable city model. What now follows is the discussion on the evolution of policies towards informal urbanisation. The Evolution of Policies towards Informal Urbanisation Settlement Demolition Policies The policies towards informal urbanisation have coincided with the stages of conceptualisation of the phenomenon. Prior to the 1960s and the findings of Mangin, Turner and Abrams, informal settlements were perceived as a threat to political stability. The terms used to refer to this kind of development, such as “urban cancer” demonstrated the conventional wisdom regarding the marginal or semi-integrated forms of urbanisation. These attitudes, Gilbert and Ward demonstrated had no empirical evidence (Gilbert and Ward, 1985) and later studies demonstrate that overall the social and political attitudes of the settlers were fairly conservative (Cornelius, 1975; Castillo, 2000). In Mexico City for example, even with the lack of “formal planning” ad-hoc responses by the state were utilised from the 1940s to the 1960s to deal with unforeseen growth and occupation of land. These responses sometimes included relocation, granting “official” land tenure, resolving disputes among owners and settlers or servicing occupied areas. In some cases, political commitments required the eviction of squatters and the eradication of slums (Castillo, 2000). These kind of interventions are quite similar to those carried out in Nairobi from the 1960s through the 1980s, it is however evident that Nairobi City 42 Council and the country as a whole, lacks clear and specific policies for housing, land use planning and land management (Syagga, 2002). The official state policy during these years was a balance between co-optation and confrontation. The optimistic policies of the 1960s and early 1970s that aimed to minimise slums through the construction of public housing, shifted to more realistic policies where informality was assumed as a given, an on-going, permanent process, at least in the short and medium term (Schteingart et al. 1994 quoted in Castillo 2000:26). The spatial strategies adopted in the 1960s propagated a strong regulatory intervention (based on Western minimum standards and solutions), was necessary in order to control, direct and rationalise urban growth. This was very much in line with the Rational City concepts propagated by Le Corbusier in the 1940s, where the principal planning tool used for urban development, was the Master Plan. During the late 1960s and early 1970s a major debate arose regarding Third World Cities, with the main issue being; how to guide the rapid urbanisation process which was taking place in these cities and the question of who makes decisions and at what level? In this regard, it can be seen that; autonomy and heteronomy play a major role in the urbanisation process, however since urbanity is materialised by the construction of a “physical thing”-the city, these concepts for purposes of space production, have to operate in tandem with the notion of private and public urban space. Decisions made at domestic level can be seen as being autonomous, and generally control the production of private urban space. While decisions made beyond the domestic realm can be considered heteronymous, and control the production of public urban space. Turner, 1976 has discussed these concepts at length and notes that “the partially unresolved problem is to identify the practical and necessary limits of heteronomy and it’s opposite, autonomy” (Turner, 1976:17). These limits are crucial in the urban process, because in the creation of a city, different decisions are to be made at different levels, and therefore by implication the decision makers are also crucial. Bureaucratic heteronymous systems produce, products of high standards, at great cost, and of dubious value, while autonomous systems produce products of extremely varied standards, but at low cost and 43 of high-use-value. It is these varied standards that led many governments to adopt policies of demolition, with a view of producing products/settlements of uniform standards. However uniformity quite often creates monotony of urban environments, which can be oppressive and could do with variety. Appreciating the various levels of decision making, can enable governments create appropriate policies that can guide integrated urban development. The demolition policies of the 1960s and 70s did not take cognisance of decision making at grassroots levels. Regularisation Policies In a very general way, informal urbanisation can be considered to be the forms of urban development that take place outside the legal, planned and regulated channels of city making. “Irregularity enters our consciousness the moment that the state decides to normalise practices once considered marginal or irregular”. Ward defines irregular settlements as; Those which develop outside the law through invasion, through illegal subdivision of land without proper permission and adequate service provision, through illegal sale or cession of land to which the vendors have no alienable rights. They are usually, but not exclusively, low-income areas and are commonly referred to by a wide variety of local generic names in different countries (Ward 1983:35, quoted in Castillo, 2000:23). It is for the above reasons that policies towards regularisation were initiated. In the 1970s the new policies that emerged out of consensus and consolidated at the Habitat 1 conference in 1976 included: site and services and self-help housing projects; core housing; slum and squatter settlement upgrading; tenure regularisation programmes; the stimulation of small-scale enterprises and informal sector activities in project areas; and an attempt to expand the provision of public services (Burgess, et al. 1997). During this period, most developing countries were implementing a diverse set of actions dealing with informality. On the one hand, the planners were pushing for a stronger social housing policy with finished and progressive housing programmes; while on the other hand, they accepted informality as a legitimate solution to the problem of housing the urban poor. At the same time, many countries, Kenya included, through the influence of 44 the World Bank and other development organisations, instituted programmes such as sites and services. Nairobi’s Dandora development, which was meant to make available 6000 serviced plots, is an example of these interventions. Regularisation as an intervention strategy to informality then became the dominant policy in the post 1970s period, although it had a limited impact in Nairobi. In addition, literature seems to be divided over the success of regularisation, quite often the defence for regularisation has been that it is seen as a catalyst for future improvements to the houses themselves. According to this line of thought, insecurity of tenure, as well as fear of eviction is what limited the citizens’ involvement both in time and economic terms (De Soto, 2001). By regularization, officials aimed for an improvement in the conditions of the houses, this assumption has however been challenged by scholars who argue that security in tenure is not always important or necessary for improvements in housing and that time lived in a settlement is as important as anything else (Angel, 1983; Schteingart and Boltvinik, 1997 in Castillo, 2000:27). To justify regularisation, De Soto, 2001 argued that the poverty of the Third World is not the culturally based phenomenon assumed by so many writing in this area, but rather grounded in well documented property rights. People in poor countries exist as squatters, without legal title to their land, homes or business. If security of land tenure plays an important role, as established by Turner earlier on, then it can also be argued that infrastructure carries a symbolic dimension since it gives security in the land tenure, when legal tenure is not yet acquired (Syagga, 2002). In addition, “perception of security is actually as important as real security of tenure” (Varley, 1989; Castillo, 2000:27). Other authors have posited that regularization is intrinsically connected to political manipulation (Castells, 1983; Fernandes and Varley, 1998; Schteingart, 1981) (Castillo, 2000:27). Another critique with regard to regularisation states that the moment the land becomes legal it joins the land market, resulting in the displacement of original settlers by making the expenses associated with formality a burden to residents. This may not always be true, evidence from Nairobi shows that the costs of informality can be enormous. For example the costs of occupational and environmental hazards that informality creates, can be quite high (Lamba, 1994; NISCC, 1997). 45 There also seems to be a dominant notion in the literature that somehow the poor have to be protected from the effects of owning property, be it from the costs of the regularization or from the ability to enter the land and housing market through the sale of their property. Both these charges are flawed since this research and other empirical evidence (Mitullah and Kibwana, 1998; Syagga, 2002; Castillo, 2000; De Soto, 2001) show that the costs most settlers have to pay for services are higher before than after regularisation. In Nairobi for example, water costs 8 times as much in informal areas compared to formal areas (Syagga, 2002:50). The notion that the poor have to be protected on account of the perverse effects of entering the market, is a position ideologically based on the paternalistic premise that the state must protect the poor, rather than allow them to make their own rational and individual choices (Castillo, 2000:28). If land and housing prices increase, the settlers will surely benefit from the increased values, since they alone decide what to do with their property. On top of that, measures to `protect` the poor through the confinement of property and selling rights usually backfire (Azuela and Duhau, 1998 in Castillo, 2000). The low cost of the regularisation programme, which is self-financed, and the high-yield political returns make it extremely attractive to use as social policy. Besides the standard regularisation/upgrading/servicing programmes, other comprehensive approaches include a combination of legal, fiscal, regulatory and lands policies. The problem with regularisation policies is that they have focused primarily on the issue of tenure, rather than on a broader conception of the urbanisation logic. In other words, the assumption that only through the legal transformation, the informal segments of the city could be incorporated, ignored that regularisation was just a minor step in incorporating informal settlements to the city. The complimentary dimensions of the urban problems related to mobility, access to services and quality of life and provision of infrastructure, have been completely ignored (Castillo, 2000:29). Another misconception in regularisation is that, policies assume secure tenure means the granting of individual title deeds. Evidence from Voi town, shows that security of tenure can be granted to a group of people, through “community land trust”, a situation where individuals have user rights, without owning individual titles (NISCC, 1997:8). 46 Enablement Policies Caminos and Geothert, 1978 saw the problem of urbanisation in developing countries as a problem of unstable political and economic systems, they also observed that social well being was the privilege of a minority in power and the settlement process was largely out of control. Illegal developments are a consequence of unrealistic rules. Most planning and building regulations in developing countries have been adopted directly and uncritically from standards used in the economically developed countries of Europe and the USA (Caminos and Geothert, 1978:198). A limited sector of the population can meet these standards and as a result, most of the dwellings built are below such standards and are therefore illegal (De Soto, 2001; See study model Fig.2.1). In an attempt to try and bridge the gap between supply and demand for dwellings, urban researchers in the 1970s based their research on the growth and redistribution theory plus basic needs theory. These researches resulted in strategies for: site and service and selfhelp housing projects; core housing, slum and squatter settlement upgrading; tenure regularisation programmes; improved access to financial, managerial and technical assistance; the stimulation of small-scale enterprises and informal sector activities in project areas; and an attempt to expand the provision of public services (Burgess, et al. 1997:113). However, by the end of the seventies, these approaches could not provide affordable solutions for the poor, and the solutions were not replicable. In the 1980s, emphasis was on “integrated development projects” sometimes combined with site and services to permit densification. These approaches were also rendered unworkable due to the debt crisis and the structural adjustment problems of the mid 1980s. By the end of the 1980s, the “affordability-cost recovery-replicability” formula was not achievable either, leading to a change of strategy at the beginning f the 1990s. The policy measures in the 90s reflected the general goals of neo-liberal analysis: elimination of supply-and demand-side constrains, withdrawal of state and encouragement of privatisation, deregulation and regulatory reforms etc. These conditions made the neo-liberals turn to the concept of “enablement”, which was to provide the theoretical underpinning of the new policy framework (Burgess, et al. 1997). 47 During this period, cities were increasingly seen as engines of economic growth, and restrictive building and land use standards were increasingly being phased out (Syagga, 2002). All the above efforts have not generated sustainable urban development, as we get into the new millennium; the dominant orthodoxy is now sustainable livelihoods theory, with a focus on poverty eradication. With regard to urban policy, emphasis will be laid on privatisation and on private/public sector partnerships. All said and done, it is evident that efforts made in the last forty years or so have not been able to cope with the demand for affordable urban goods and services. It is unlikely that the new sustainable livelihoods strategy will solve the problems of the urban poor and therefore those of informality, as the capital required is out of reach for most third world countries. The limited response by the Kenyan government to deal with issues of informal urbanisation were due in part to an unsubstantiated fear that any policy that would foster development would mean “opening the gates” to more illegality (NISCC, 1997; Fernandes and Varley, 1998). Since the 1980s a number of agencies, programmes and approaches have been tried in addressing the problem of informal urbanisation. These have usually been disjointed efforts with overlapping goals and responsibilities, most of them have been reactive by nature in that they address the effects and not the causes of the problem (Syagga, 2002). Examples of these agencies operating in Nairobi include; Pamoja Trust, Maji Na Ufanisi, Kituo cha Sheria to name but a few. The enablement concept that the state has adopted in line with global preferences has had very little impact on informal urbanisation, as the trunk infrastructure the state was supposed to provide for marketised land development and the upgrading of settlements has not been forthcoming. Another shortcoming of the enablement policy is that different stakeholders who may own private urban property have different capabilities to transform or urbanise these properties. This may lead to uncoordinated procurement of urban space, although this may generate the requisite variety, it may require some level of heteronymous decision making in order to serve the collective good of the whole community/neighbourhood. On the other hand, autonomy allows people to invest their energy and initiative in urban 48 space production, which has been proven to be a sustainable approach to urban space production as per Habitat’s Local Agenda 21(UNCHS, 1996:407-9). The above discussion on policies raises fundamental issues regarding informality and its impact on the urban process of third world cities. It seems necessary to take advantage of the positive attributes of informality, which can then form the basis for a suitable city model for developing countries. I now turn to the argument for the case of “Diverse Informalities”, as a basis for creating such a city model. Re-conceptualising Informality (The case for “Diverse Informalities”) For the purposes of this thesis, informality has to be re-conceptualised through a set of new lenses in order to gain a deeper understanding of the urban process in Nairobi. As shown earlier most studies on informality treat the phenomenon as homogeneous, yet this may not be the case in Nairobi. This is the reason for opting to study this phenomenon as a heterogeneous one or diverse, and if it turns out to be homogeneous, so be it. The urban process involves the concentration of people in one place and the construction of the physical structures that support their existence in the said place, resulting into cities. Rossi sees the city as a man-made object consisting of two main elements, housing areas and monuments. The city has always been characterised largely by the individual dwelling. It can be said that cities in which the residential aspect was not present do not exist or have not existed; and where the residential function was initially subordinated to other artefacts ( the castle, the military encampment), a modification of the city’s structure soon occurred to confer importance to the individual dwelling (Rossi, 1982:70). Similarly, Turner argues that; Globally homes and residential areas occupy at least one half of all built-up land, and that three-quarters of all human lifetime is spent there and about half of all materials and harnessed energy is used in and for homes and neighbourhoods (Turner, in Burgess, et al. 1997:166). The dominance of residences in city composition, and the fact that informal urban processes are predominantly residential justifies the indulgence of the discourse in 49 residential processes, for they are essentially urban processes. In Kenya for example, most informal urban processes are exemplified by human settlements. The urban process in most third world cities has been basically informal, but in the case of Nairobi, this informality has not been homogeneous. Similarly, in Mexico City, informality is heterogeneous, that is the reason why Castillo, 2000 used the term “urbanisms of the informal” as a way of re-conceptualizing the complex nature of the phenomenon of informality. In many cases the scale of informal processes is quite large; in Brazil for example 60 to 70 per cent of the entire region’s construction is produced informally. On this account, De Soto observes that; the extralegal systems constitute the most important rebellion against the status quo in the history of the developing countries since independence, and in the countries of the former Soviet Union since the collapse of communism (De Soto, 2001:86). It should also be highlighted that formal law is losing its legitimacy in many countries, as people continue to create property beyond its reach. On this premise De Soto further observes that; If the legal system does not facilitate the people’s needs and ambitions, they will move out of the system in droves (De Soto, 2001:177). Legality has dominated most urban studies, where informal urban processes are addressed without spatial considerations; very few authors have shown any awareness of space. This study will focus on the spatial aspects of informal urban processes, it will also re-emphasise the centrality of space and the role of design in urbanisation, a role which has increasingly been diminishing. Fig.2.1 below shows the proposed model through which the study can fill the current lacuna in the informal urbanisation discourse for most African cities; this model is based on empirical evidence from Nairobi. It is the conceptual tool that will guide the understanding of the urban process in Nairobi. 50 Urbanisation Illegal Formal Serves small Pop. Informal/ Diverse Serves a large Pop. Conforms to Legal Statutes Legal Survivalist; Primary Intermediate; Affluent Manipulates the Weaknesses of the Legal Framework - Extralegal Serves Small pop. Total selfinter est and disre gards the Law Ille gal It is based on the assumption that society adopts a capitalist mode of production and that society is not Fig.2.1 Nairobi’s Urbanisation Study Model. egalitarian. Source: Author The urbanisation process can be divided into three categories for purposes of this study, thus the formal, the informal/diverse and the illegal. Both the formal and the illegal serve a very small proportion of the population, the informal or diverse which forms the core of this thesis serves the majority of the population. Informal/diverse urbanisation can be further broken down into the sub-categories of; survival, primary, intermediate and affluent, these diverse informalities are discussed in detail in chapter four. In discussing informal urbanisation, informality will encompass the casual processes and unofficial methods of procurement of urban space. Almost invariably, at least one aspect of the urban space (Private sector generated), is informal; it may lack formal land tenure; failure to obtain development permission; failure to satisfy planning and building regulations or disregard of rent controls. It is financed, built and exchanged outside the formal systems for mortgage lending, construction, rent control and sale (Rakodi, 1997). 51 I need to state here that there may sometimes be a tendency to romanticise informality, as it apparently functions adequately for the urban poor. However, at the lowest level, informality can be seen as a survivalist strategy, which comes into play due to the collapse or inadequacy of formal public services. The collapse of public services occurs when the state abdicates its functions of creating some level of equity among the citizens; without equity the working classes tend to be marginalised by the state, leading to informal processes (Rakodi, 1997). This means that informality comes into play by default. There also, has been a tendency for policy makers in most post-colonial countries to keep blaming colonialism for the predicament many cities face today. This is not tenable as many third world cities have been independent for approximately 40 years, and yet to date they have not consolidated their governance/legal structures (Chabal and Daloz, 1999). Colonialism can not be blamed for ever for the failings of these cities. The African Big Man syndrome of patronage has played a major role in the current dilemma, a dilemma that has also been supported by international aid agencies that have financed corrupt African regimes. With regard to governance at local level, Turner’s advocacy for autonomy at local levels may be laudable, however in most third world cities the CBOs and NGOs that operate at local level may not always be impartial. Evidence from Nairobi shows that many CBOs are one wo/man shows, they lack transparency and accountability. The urban poor are also unable to benefit from the ne-oliberalist’s view of growth through market forces, as market forces are based on economic gain as opposed to social justice, and the urban poor badly require social justice (Rakodi, 1997; Simone, 2002&2003). From the foregoing, it is evident that informal processes are going to increasingly impact and shape the urban process of third world cities. Whereas the strategy of master planning in the 1960s/70s was not tenable, the strategy of enablement in the 1980s actually degenerated into a theoretical discourse with little physical evidence of its success. (Syagga, 2002). The strategies in diverse informalities which create “diverse urbanisms” have to be understood in order to adequately address the mismatch between supply and demand of urban goods and services in many third world cities. It has been shown that space/spatiality is a major variable in the informal urban process. In fact many actors often times adapt strategies that have spatial implications in their 52 endeavour of accessing urban goods and services. The discussion that now follows, addresses informality and the centrality of space. Informality and the Centrality of Space Rather than being just an effect, space can facilitate or hinder social and economic relationships, space therefore creates an important role in informal urbanisation as it mediates socio/economic relationships. Many studies on informality rarely address the spatial dimension, space and its manipulation is at the core of this thesis. During the 1970s, a number of urban researchers looked at the physical patterns of housing systems in order to compare how efficient they were in terms of land utilisation and provision of infrastructure and services (Bazant S 1978; Bazant S et al. 1974; Caminos and Goethert 1976; Caminos and Goethert 1978; Caminos et al. 1969; World Bank. Urban Development and Padlo 1981- the “Bertand Model”). This work associated with the boom in site and services projects, argued that for each socio-economic condition, there were optimum patterns of development (Castillo, 2000). These studies were commissioned as a result of the rapid informal urbanisation that was then taking place in most third world cities. It goes without saying that the central issue in these studies was space. The optimum solutions emanating from these studies were based on two variables: efficient patterns of settlements and the level of services provided, optimality and efficiency related to the street-lot frontage. These studies facilitated the formulation of certain urban policies that were tested in the 1970s particularly in the site and service schemes of the time. Space has also been used as an analytical tool in the theoretical discourse of the Urban Informal Sector (UIS). Dierwechter, 2002 engages in a theoretical discourse on the Urban Informal Sector (UIS) and maps out six cities for purposes of spatial theorisation. These cities are; the twin city, the ecological city, the city of systems, the behavioural city, the malleable city and the differentiated city. He argues that most research in the UIS is aspatial and that only very few authors have shown any awareness of space. He indulges in “spatialising theory rather than theorising space”, and therefore once again emphasising the centrality of space in informal urbanisation (Dierwechter, 2002). 53 During the post-colonial period, as mentioned earlier, spatial segregation continued to be reinforced, but this time more as a socio-economic and cultural stratification as opposed to racial. Earlier on, theories of residential differentiation had begun with the Chicago School in the 1920/30s, which saw city growth as a colonisation of different “quarters” by different income and ethnic groups. (UNCHS, 2003:17). Their successors, the neo-liberal urban economists, regarded informal settlements as the natural response of the market in providing housing and services for poor people: the housing and services that they can afford (UNCHS, 2003). In general, three types of informal settlements can be identified; squatter settlements, illegal subdivisions of either government or private land and illegal transformations of government or private buildings (Syagga, 2002; UNCHS, 2003). One major characteristic of informal settlements is that most residents are poor, and in discussing poverty, the spatial dimension has to be addressed. Poverty and slums (informal settlements) are closely related and mutually reinforcing. The juxtaposition of extreme wealth and poverty is not merely spatial: it is a functional relation: rich and poor define each other. Similarly it can be argued that formal and informal define each other, i.e. for there to be an informal situation, there must be a formal one. Because of this symbiotic relationship it seems inevitable that most cities have slums. Slums have grown as a seemingly inevitable part of modern life. Low-income people find cheap accommodation helpful in their need to keep housekeeping costs low enough to afford. To do this, they tolerate much less than ideal conditions no doubt hoping to improve and move to somewhere better (UNCHS, 2003:62). The informal city and the city of illegality, which comprises the slums of the developing mega cities, have been shown by many scholars to be the base of the informal sector. This is where services are poor or non existent; where residents are invisible to the legal statutes and systems; and where harassment by the authorities is commonplace (UNCHS, 2003). Space plays a central role in the formation of informal settlements, these settlements can be categorised into three categories as earlier mentioned. The first category of squatting became a large and profitable business in Nairobi, in the post independence 54 period. This business is often carried out with the active, if clandestine, participation of politicians, policemen and privateers of all kinds. In most cases, the prime target was public land or that owned by absentee landlords (UNCHS, 2003:82). Contrary to popular belief, access to squatter settlements is rarely free and, within most settlements, entry fees are often charged by the person or group who exerts control over the settlement and the distribution of land.10 In Nairobi for example, the area chief distributes public land to structure builders for a certain consideration. The structure owners in turn build structures and rent them out to tenants, with the result that the majority of residents in these settlements are tenants (NISCC, 1997; Syagga, 2002). Squatter settlements are characterised with buildings built of all sorts of makeshift materials, e.g. cardboard, polythene, re-used iron sheets, second hand timber panels etc. There are almost no infrastructural services in these settlements; all the circulation paths/roads get formed by the constant movement of people on the natural ground in the gaps left between the structures. Water is sourced from mobile vendors, while the dominant mode of sanitation is use of pit latrines. The physical fabric in these settlements remains poor, as the structure owners cannot risk the costs of improvement, due to the insecure tenure of settlement. This is because; the structures can be demolished without notice, by absentee landlords or the government (Matrix Development Consultants, 1993). Within these settlements, there exists a range of actors from owner occupiers to tenants, subsistence landlords to absentee petty-capitalist landlords, and developers to rent agents and protection racketeers. Variety also exists in the legal status of these settlements; while squatter settlements begin with an illegal occupation of land, over time some form of security of tenure, if not formally recognised legal title, can be transferred to the residents. In time, de facto legality can be implied by the simple fact of the settlement not being demolished, and /or public services being provided (UNCHS, 2003:83). The second category of informal settlements is unauthorised land developments or illegal subdivisions. Illegal subdivisions refer to settlements where the land has been subdivided, 10 See the case of Mukuru Kwa Njenga in chapter 4. 55 resold, rented or leased by its legal owner to people who build their houses/businesses upon the plots that they buy. These settlements are illegal owing to any combination of the following: low standards of services or infrastructure; breaches of land zoning; lack of planning and building permits; or the irregular nature of the land subdivision. In some cases, farmers have found that the most profitable “crop” for their land is housing. Periurban land is transformed from agricultural to urban use by land owners who divide it into plots for housing. As in squatter settlements, most occupants of illegal subdivisions build, extend and improve their own housing over time, and consider themselves to be owner occupiers, which, de facto, they are (UNCHS, 2003:84). In illegal subdivisions, the buildings are normally built of permanent materials, the designs of these buildings may be sourced formally from registered consultants, but they may not have the necessary local authority approvals, as shown by evidence from Nairobi. The land owner will most likely have subdivided the land using registered surveyors, and the subdivisions could even have official titles. In general only minimal services may be provided in these settlements, e.g. piped water and unpaved roads. In settlements arising out of subdivisions, owners/developers have to source power and other urban services through their own means (Kamau and Gitau in Hansen and Vaa, 2004). The third category of informal settlements is the illegal transformations of formal housing through the process of extensions and alterations by users without permission, or in ways that do not fulfil standards. This is now very common in government built estates all around the world. The transformations which “informalise” the government built estates often represent better conditions (better physical conditions, more services, and more space per occupant, higher value, and better value for money) than the pre-existing housing (Tipple, 2001; Soliman, 2002). The ex-formal settlements generate a new hybrid architecture where the formal and the informal merge, in fact over time, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish which part of the built fabric was originally formal (De Soto, 2001). These transformations come about due to the ability of the transformers to manipulate the existing laws in order to maximise on the economic potential of their plots. The net effect of these settlements is 56 that the carrying capacity of the infrastructural services i.e. water supply, power supply, sewage/drainage, road network etc. are stretched to high limits. The inability of postcolonial development structures to provide affordable serviced land leads to these transformations together with affluent informalities by the well to do, as outlined in Fig.2.1 and discussed in detail in chapter four. All the above informalities are possible because of the availability of space, irrespective of services and legal statutes; in any case the statutes are manipulated to the advantage of the interested parties. This further confirms the centrality of space in the informal urban process. The foregoing theoretical and conceptual framework has highlighted the centrality of space in the discussion of the phenomenon of informality. What follows now, is the discussion on the urban history of Nairobi, where space as above will be shown to have played a central role, in the making of this urban history. 57 3. THE URBAN HISTORY OF NAIROBI Colonial Nairobi Introduction Nairobi like many African cities was established as a result of colonialism. The Berlin Conference of 1884 and the scramble and partition for Africa led to the establishment of African states and thereafter African cities (Ayittey, 1991). The bulk of the interior at this time appears to have been characterised by dispersed settlement, although urban centres may have left negligible archaeological traces due to the organic materials in which they were constructed (Burton, 2002:4). These conditions seem to be characteristic to those of Nairobi before the arrival of the railway, when the Maasai people used to graze and water their cattle at what they called “Enkare Nyaribe” meaning a place of cold water (Thornton White et al., 1948:10). According to Zwanenberg and King, some evidence suggests that the site was earlier used for trading by Kikuyu and Maasai women (Zwanenberg and King, 1975:263). At that time, the East African region was already integrated in the Arabic-Oriental trade with its centre at Zanzibar and on the coast around Mombasa, in what Samir Amin has called the pre-mercantile period in Africa’s history (Amin, 1976). When the Imperial British East Africa (IBEA) was founded in 1888, it based its economy on the continuation of an already existing trade with ivory tusks, bee-wax, hides and skins, which was older than the East African slave trade (Emig and Ismail, 1980:7).11 The Founding Years 1899-1905 Nairobi was established more than 100 years ago as a transit point for the Uganda Railway. The Nairobi site was situated about midway between the port of Mombasa (327 miles away) and Kisumu on Lake Victoria (257 miles away) which were to be the two termini of the railway line (Thornton White et al, 1948:10). Fig.3.1 shows the contextual location of Nairobi. It was made a transit point based on the government administrative 11 The pre-mercantile trade was on a barter basis, which later changed to a monetary capitalist mode after the establishment of colonial rule. 58 structure and some primary industries that processed raw materials for export to European industries.12 From the beginning between, Nairobi was to be one of Africa’s largest inland cities and an important location for industry. In 1900, Nairobi was designated as a town of 18Km² of “previously owner-less land”, and by 1905 it was the capital of the East African colony (Hirst, 1994:30). Five years after being founded, Nairobi still had no town plan; it was all spontaneous growth (See Fig.3.2). Although Hirst alleges that there was no town plan for Nairobi, in fact there was the 1898 Plan for a Railway Town which was the outcome of a welldefined engineering task. The plan was clear cut in its “technical” handling of social questions and highly efficient in its implementation of the class/race segregation and division of space. The plan was part of the British strategy of gaining political sovereignty over the Upper Nile region and Uganda. From the very beginning, it is evident that appropriation of space, without consideration of local/indigenous land uses, played a key role in the establishment of Nairobi. The interests of the British government was to layout a town in the interior from where the “King’s Rifles” could control this part of East Africa. The railway line and the town plan were a dictate by the rulers in London, spelling out a political message – to be heralded by the minds of the railway engineers (Emig and Ismail, 1980:14). The Plan for a Railway Town, only took into consideration the European employees of the Railway, and the European and Asian traders. The plan completely neglected the Asian labourers or Coolies and Africans.13 Nairobi was going to be a Railway Town for Europeans with a mixed European and Asian trading post (Emig and Ismail, 1980:9). It should however be pointed out that Navanlinna, 1996 argues that there is no evidence to show that the Plan expressed notions of segregation by class and race. She goes into rational and technical arguments to justify her opinion (Nevanlinna, 1996:96). 12 Unlike most Western Cities which were established because of trade and industry, Nairobi was established as an administrative and transit centre. A small industrial base was established to service the Western market. 13 This act of ignoring a section of the population, was later to haunt Nairobi, and is partly the reason for the rapid informal urban process. 59 Fig.3.1 Contextual Location of Nairobi. Source Adopted from Burton, 2002:2 60 Fig.3.2 Nairobi Layout c 1900, Source: Adopted from Thornton White et al. 1948:11 The town soon began to grow rapidly, and for the first time there was a need to demarcate the municipal boundary Fig.3.3. The outer borders of the town were decided arbitrarily, but were drawn to encompass the entire Railway complex, the Indian Bazaar, the Administration and the European Business Centre, the Railway quarters, the Dhobi quarters and European suburbs area. The centre of this circular boundary was at the Government Offices and formed a radius of approximately 2.4 Km (1.5 Miles) (Halliman and Morgan, 1967). During this period, Commissioner Charles Eliot introduced a hut tax and encouraged European settlement based upon a policy of integrated development. Eliot found two individuals who were to shape, not just Nairobi, but the whole ecosystem, by introducing industrialised agriculture and forestry, and a national economy based on resource extraction.14 The two men, Lord Delamere and Ewart Grogan, they were among the 14 It is during this period that the Western monetary and capitalist economy was being entrenched. 61 pioneer European settlers in Kenya. With the arrival of these early settlers, Eliot’s vision of integrated development was swiftly changed, and separate development of the various races established as policy. Here was to be clearly the beginning of social, political and economic exclusion of the African majority. Nairobi grew up in a haphazard way, with the usual wasteful and ugly results. Like all new towns in new countries, it was utilitarian in origin and unplanned in adolescence (Elspeth Huxley, 1935- Quoted in Hirst, 1994:31). At this time, the removal of the town from the site was still being debated, but nothing came of this debate, as nobody was absolutely sure how long the place would be there. Writing in 1906, Winston Churchill argued that; It is now too late to change, and thus lack of foresight and of a comprehensive view leaves its permanent imprint upon the countenance of a new country. In “My African Journey”, 1907 Churchill further observed that; There already in miniature all the elements of keen political and racial discord, all the materials for hot and acrimonious debate. The Whiteman versus the Black; the Indian versus both; the settler versus planter; the town contrasted with country; the official class against the unofficial; the coast and the highlands….in truth the problems of East Africa are the problems of the World. We see social, racial and economic stresses which rack modern society already at work here. At the beginning, Nairobi did not have an African area or quarter, but in the East the Railway was establishing the concept of working class dwellings or landies. The first African housing was constructed near the shunting yards along what came to be known as Landhies Road (Anderson, in Burton, 2002:141). Concurrently most of the Indians in Nairobi, about 3,000 were all pushed into the six acres of the Indian commercial district (the Bazaar). Due to this overcrowding in the Bazaar, plague broke out in both 1902 and 1904. 62 Fig.3.3 Layout of Nairobi c 1905, Source: Adopted from Hirst 1994:37 63 Bazaar Street c190415 Bazaar Street c 1924 Biashara Street 2005 Fig.3.4, Evolution of Biashara Street. Source; Nevanlinna, 1996:102; Burton, 2002:205; Author, 2005 The Consolidation Period 1906-1926 By 1906, the colonisation of the city was being consolidated and designed, based on the interests of the white settler population, and ignoring the interests of the Indians. The 15 The current Biashara Street was previously called Bazaar Street 64 Africans were not even considered residents, and could not hold freehold property in the city-even if they could afford it (Hirst, 199:50). Eighty per cent of the city was reserved for ten per cent of the residents.16 It was a “garden city” development based upon income and social status-with the tropical complications of race and culture (Hirst, 1994:50). From the beginning there were two Nairobi’s; Residential areas for Europeans and Asians and official housing for Africans. But this was only half of it-the serviced half. From 1890, all the other Africans who were not employed by Europeans had been building subsistence settlements through an independent informal sector development without the benefit of Town Planning. Fig.3.5 illustrates what was happening at this time. As can be seen there were several informal settlements for Africans including Kangemi, Kawangware, Kileleshwa, Kibera, Masikini, Pumwani, Pangani and Mombasa. This can be said to be the beginning of the formal/informal spatial divide, which has persisted to date, and is at the core of this thesis. By 1921, 12,088 Africans were living in these eight informal “villages”. During this period, single women were already prominent among the property owners of Pangani, and numerous lodging houses offered nightly accommodation to African travellers and migrant workers (Burja, 1975).17 Nairobi’s European citizenry had however long viewed the town’s unregulated African villages as havens of disease and criminality, and advocated for their demolition as a sign of better social control and improved public health (Anderson in Burton, 2002:142). Villages like; Pumwani, Kawangware, Kibera and Kangemi are some of the original colonial era villages, that are still among the main underdeveloped or slum areas of the city today. During this period too, an absolute authoritarian system was established under the governor. This was a system where the governed had little, or no participation in the decision-making processes that affected their lives. There was massive political intervention in the economy by the colonial state, including the transformation of 16 The marginalisation of Indians and Africans got institutionalised and became a structural feature of the urban process of Nairobi. 17 The single women of Nairobi can be regarded as some of the earliest Kenyan people to fully embrace the capitalist market economy. 65 Africans into wage labourers.18 At the same time, the commoditisation of land had enabled Grogan (a pioneer settler), to grab “Enkare Nyaribe” itself. Grogan and Sharif Jaffer had acquired 120 acres of land, from Museum Hill to Racecourse Road on a 99year lease, for a nominal fee. He later bought Jaffer out for £3,000 in 1910, and by 1929, Grogan was asking for £60,000 for it. Some plots were sold, the rest went for £180,000 in 1948 (Hirst, 1994:45). At the same time, racial practices in place were conveniently disguised as zoning. Although the 1923 Devonshire White Paper prohibited the separation of the races in the Townships by legislation, the separation was done without the legislation. The government openly prevented non-Europeans from buying plots in certain parts of Nairobi (Hirst, 1994:51). In an attempt to try and create a new residential area for Indians in 1919, three informal villages including Mombasa, Pangani and Masikini, near Forest Road were pulled down. All the people in these villages were moved to Pumwani the designated “Official Location” for Africans. They still had to build the houses themselves, on a rough street plan called Pumwani. This in a sense was the first experimental site and service scheme in Nairobi (Nevanlinna, 1996:222). Fig.3.6 shows the layout plan of Pumwani and image of the 1980s. There has been very little transformation in the 30 year period. In this period of consolidation, 18,000 Africans or 60% of the town’s population occupied only 5% of the town’s land, at the same time in Kilimani for example, 200 people or 1% of the town’s population lived on 5% of the town’s land (Hirst, 1994:53).19 It was not until 1921, that the municipality accepted responsibility for the provision of houses for Africans, consequently “Kariokor” bachelor quarters became the first housing project on which money £13,000 was spent. The buildings were very basic, no more than a kind of barracks or hostel, with dormitories. The scheme was a failure, and one third of the space remained empty, until the place was partitioned into “cubicles” for men only (Hake, 1977, Hirst, 1994:63). Consciously or unconsciously, the European settlers designed their city around a personalised transport; first the horses, bikes and rickshaws, then the motor car ruled. The 18 This act of transforming Africans into wage labourers was supposed to severe them from their traditional ways of life and integrating them into the capitalist economy – See Harvey, 1986. 19 This situation is similar to the conditions prevailing today, as approximately 60% of Nairobi’s population lives in informal settlements, which occupy about 5% of the land area. See Matrix Development Consultants, 1993; Syagga, 2002; NISCC, 1997. 66 first car appeared in Nairobi in 1902, and by 1928 with 5,000 cars, Nairobi was the most per capita motor-ridden city in the world for Europeans (Hirst, 1994:65).20 In addition to privatised transport, Nairobi was developed as an energy-intensive city with much centralised services, with people commuting for both business and pleasure. This was quite unlike similar sized cities in Europe or Asia at that time (Hirst, 1994:65). Most preindustrial towns were coal-powered, but the “city in the sun” wasn’t, it was powered by oil, steam and latter electricity…..totally dependent on outside deliveries from its bigger system. Fig.3.5 Nairobi Layout c1926, Source: Adopted from Hirst, 1994:50/51 At the end of the consolidation period in 1926, Europeans owned plots totalling 2,700 acres while the Indians only had 300 acres for their residential purposes. The Africans 20 Harvey, 1986 argues that space and time are forms of social power, therefore in order to control time and space, a car and home ownership make and attractive combination – See chapter 2. 67 astonishingly, didn’t have any except the nominal official housing. Some Africans however owned property; these were single women who were prominent in the development of Pangani village (Burja, 1975; Burton, 2002). They built “Swahili” square houses, where they lived in one room and rented out the others. They enjoyed some minimal security of tenure under the English law called USUFRUCT, which is the right of enjoying the use and advantages of another’s property short of destruction or waste of its substance (Hirst, 1994:62). Also, in 1926 a Town Hall that the settler capital could be proud of was built. The architect of the building, Sir Herbert Baker had emphasised the connection between architecture and political progress-and the home making inclination (Hirst, 1994:82). The Town Hall, the municipal offices, the law courts and other public buildings were to provide a combined effect of power. Due to the rapid growth of the town during this period, it was decided to enlarge the municipal area in 1926 Fig.3.7.21 Prior to the enlargement of the municipal area, the municipality had tried to address the issue of African housing. After the municipality’s failure with its first African housing scheme in 1921 at Kariokor (Bachelors quarters), the government built “Starehe” for its own African employees, at a cost of £40,000. In the same year, 1926, it spent some £586,430 to house its expatriate officers (Hirst, 1994:94). 21 The decision to enlarge the municipal area was primarily a spatial one, in order to cater for urban growth. Legal considerations came into play after the spatial requirements had first been satisfied. 68 Fig.3.6 Pumwani: Layout Plan, and View,22 Source: Adopted from Nevanlinna, 1996:278 22 It is evident that by the 1980s, the original 8 roomed 1920s structure had already been thoroughly transformed into a 23 roomed structure, generally extending beyond the plot boundaries and encroaching on the road reserves. 69 Fig.3.7, Nairobi Municipal Area c 1927. Source: Adopted from Hirst, 1994:86/87 The Intermediate Period 1927-1946 By 1927, T\the capitalist mode of production had now been well established in Kenya, this allowed the colonial machine to proceed in exploiting the natural resources in this part of Africa. Nairobi had rapidly developed into a Colonial Capital City, by way of a cynical racial simplification of an alien “Class System” through a zoning policy that ensured a pattern of segregation and social stratification, which laid the foundation for massive structural maldevelopment that perpetuated informal urbanisation (Hirst, 1994:86). During this intermediate period, the Westlands and Kilimani areas were zoned for one house per acre, while the Upper Hill area was zoned for two houses per acre. Elsewhere in the city, land speculation in the 1920s raised prices, such that when they collapsed at the end of that decade, the level of debt left, threatened the future of White settlement. At the same time, the British government loathed supplying loan capital for industrial 70 development in the colonies apart from the infrastructure to get the raw materials transported, and for many years the Railway was the only industrial concern in Nairobi (Hirst, 1994:93).23 In addition, Nairobi rather than providing a basis for sustained economic growth was from the start a “parasitic city”-one that drains resources and manpower of the whole country, for the benefit of dominant urban elite. Emphasis was laid upon the importation of luxuries, rather than domestic production. Low wage levels in commerce and industry inhibited the development of a stable urban community, yet Nairobi’s African population nearly doubled between 1938 and 1947, from 40,000 to 77,000. This increase in population is attributable to rural poverty in the white highlands, where land had been expropriated by white settlers for increased mechanised agriculture, making many people landless and thereby moving into Nairobi.24 Concurrently, there was also a changed attitude by the colonial regime, which encouraged the formation of stable African urban families. The other reason for the increase of the African population was the boom in business activities as a result of the Second World War (Frederiksen in Burton, 2002; Hirst, 1994). Lonsdale posits that African householders owned only houses they themselves had built as permit-holders on crown land; they were not, strictly speaking with freehold protection. The tenants who rented their rooms were still less secure a collection of individuals with their own strategies of survival, not the incorporated members of an extended household that embodied a corporate power. This was perhaps the chief reason why Nairobi’s male workforce so long remained migrant (“Straddlers”) rather than urban and Nairobi’s women as often prostitutes as wives (Lonsdale, in Burton, 2002:217). Nearly all of Nairobi’s problems were to stem from the exploitative wage structure. African wages were lower in 1934 than in 1929. In Uganda for example, average annual earnings were 240 shillings, while in Kenya they were 60 shillings. Unlike the colonial policy in other parts of British Africa, no sustained effort was made to create either a 23 This approach to industrial development, created a dependency syndrome for manufactured goods from Western industries, which persists up to today. 24 The expropriation of land also ensured that Africans were forced to join the labour market, and into mainstream capitalist economy. 71 prosperous contented rural population , or a settled urban workforce with decent family life-in a period of substantial civic investment by…..everybody. In 1920 the direct taxation from non-natives was only £50,000 while natives paid £650,000 compared to 1921 when non-natives paid £110,000 as opposed to £500,000 paid by natives. In addition Africans had paid hut and poll tax every year since 1903. Therefore those who say “Nairobi is not an African City” may be quite wrong-Africa paid for it (Hirst, 1994:94). In the 1930s, the municipality and the state had to start planning the provision of housing, health and social services for the workers of the urban employers, who needed their increasing skills. In response to these demands, the bachelor housing was built, based on the bed-space concept i.e. three bed-spaces in a 10´x12´ room as the standard (Hirst, 1994:96). In fact today’s informal settlements have adopted this kind of standard as they are also growing on a 10´x12´ room module.25 One of the fundamental changes that took place in the early 1930s was that the “amateur” period of civic management was over. Civic authorities had to lean on professionals. The Town Clerk now had to be a lawyer, and a Local Public Health Authority had to be established. In addition, in 1934 Mr. Howard Humphrey came to advice on the Ruiru water scheme, and the envisaged sewage works. His firm of consultants based in London became the Consulting Engineers for the long-term planning of the town (Hirst, 1994:97). Even today Howard Humphreys Consulting Engineers, still play a major role with regard to infrastructure provisioning. In the 1930s “Eastlands” which was east of Racecourse Road, as per the 1901 ordinance, housed 80% of Nairobi’s population. It was to be a working class area for both Africans and Asians, but still each group living separately. In this Eastlands area “Eastleigh” which was named in 1921, after an English railway town, was one of the few examples of “Grid Layout” development (See Fig.3.8). In recent times, the originally single-storey developments of Eastleigh have been converted into multi-storey developments. This is one of the settlements currently undergoing rapid informal urbanisation. 25 The bed space module of 10´ x 12´ has persisted, and is prevalent in present day informal settlements. See chapter 4, and the discussion of Mukuru Kwa Njenga 72 Fig.3.8 Grid Layout of Eastleigh, Source: adopted from Hirst, 1994:100 Several changes occurred between the wars. One of them was the “New Deal Thinking” which gave rise to the concept of “Functionalism” in architecture and urban planning, worldwide. Functionalism it was thought, despite existing political structures, would improve everyone’s everyday functioning (Hirst, 1994:103).26 It was on this basis that capital projects like the Group Hospital were conceived. This project was halted by the Second World War, however other sectors of the economy boomed. Traders and large farmers grew rich as programmes of social provision stagnated. Attracted by the boom, the African population soared to 70,000 in 1941, in a total population of 100,000. Almost all this new influx was housed in the new “illegal villages” (Hirst, 1994:103). It is during this period that the crucial gap between the population and available jobs widened dangerously, there was even a food shortage in 1942-43. In spite of this, some new African residential areas were built. Ziwani was built in phases like Starehe, while Kaloleni was under construction in 1944-45. Concurrently, uncontrolled “illegal” 26 Functionalism had its beginnings in the rational city concepts which were propagated by CIAM, where Le Corbusier was the protagonist. 73 building was increasing, a kind of self-help welfare. After the war, even more settlers came from Britain, with capital to “escape” from the labour governments’ welfare state, and land values in Nairobi rose. It was at this time that Leo Silberman came to Nairobi. He was a sociologist, with a reputation in South Africa and the UK. He presented his new ideas in Town Planning to the municipal authorities who bought them. According to Silbreman, there seemed to be an entirely new approach to urban Africa. This approach centred on the idea of “neighbourhoods”- separate, self-contained residential areas for workers, with their own social amenities, near their places of work (see Fig.3.10).27 These ideas led to the Master Plan for a Colonial Capital of 1948, which forms part of the next discussion. The Period of Decline After the Second World War, the position of the settlers was gradually weakened as Nairobi got a Royal Charter to be incorporated as a city (Hirst, 1994:107). In a radical departure from earlier policies that had drawn a migratory and almost entirely male labour force to the town, Nairobi’s post-war urban design was to include model estates for African workers and their families, who would become permanent citizens (Anderson in Burton, 2002:138). These were the post-war circumstances that led to the further expansion of Nairobi. The Nairobi Master Plan was a report to the then municipal council of Nairobi, in 1948, conceived as a key plan to the general physical, economic and social development of Nairobi, over a period of 25 years. It took a South African team of professionals three years to prepare.28 The multi-disciplinary team was led by; Prof. L. W. Thornton White, together with L. Silberman and P. R. Anderson. This team comprising of an Architect, a Sociologist and an Engineer respectively; was an innovative step in Town Planning history at that time, anywhere (Hirst, 1994:105). In their Master Plan, the railway and the main arterial roads had been re-aligned, but it was essentially the same colonial capital. The basic tenets of 27 This neighbourhood concept was not entirely new, as it had already been discussed in 1929 by Clarence Perry. See Samuels, I. et al. 2004: 171. 28 This Master Plan was basically a spatial disposition of urban functions – it objectively showed the centrality of space in the urban process. 74 the Master Plan were; to control private capital through public investment in infrastructure of Roads, Rail and Electricity, so as to service modern industry effectively. The plan was also to provide a technically impartial answer to the existing social problems, as expanded production meant more workers in the city, who had to be adequately housed to ensure social reproduction. Functionalism, it was widely believed that through industrialisation and technical development, all the economic and social problems of the city could be solved. Concrete, steel and lots of glass with lots of light with plenty of open spaces were an attempt in expressing universal human values as perceived by the new universal player-The Multinational Company (Emig and Ishmail, 1980).29 In the Master Plan, the planning of neighbourhoods was going to affect Africans the most-since they were going to be built by government or Nairobi Municipal Council. It was going to prove to them and the outside world that responsible good government was working (Hirst, 1994:106). The 1948 Master Plan, aimed to confine further growth within the existing boundaries of the Municipality as determined by the 1926 Feetham Commission, at 32.4Ml² (84Km²). Two exceptions were however made; part of the then Kibra area was be taken into the municipality and a small enclave of forest reserve west of Muthaiga as well as such industrial areas along the new marshalling yards as were taken up. The inclusion of these areas raised no racial or political problem. Fig.3.9 shows the central area of the 1948 Master Plan, which envisaged the Kenya Centre as the heart of the central area. On the other hand, Fig.3.10 shows the layout of a Typical Neighbourhood Unit, which was to be adopted for African housing areas.30 In 1948, there were many plans on the drawing boards, it was a busy time for architects, the economy was booming, and permitted building heights were raised so that sevenstoried office blocks were very profitable investments (Hirst, 1994:108). At the same time functionalism as a planning/design concept would free architecture from local traditions and history. Its goal was to provide a respect for universal human values (Emig and Ismail, 1980:38). 29 It is evident that the consultants were avoiding addressing the issue of African housing, instead choosing to operate under the cover of functionalism. 30 Apart from the re-alignment of the railway line from the central station, including some roads, it can be said that very few of the Master Plan’s proposals were implemented. 75 The forties and the fifties saw almost frantic activity to consolidate the Nairobi city centre, and even the idea of a Group Hospital was revived, with the King George VI (Currently Kenyatta) hospital for all races opening in 1950. The number of schools increased to take 3,000 children. These schools were however not entirely built in neighbourhoods as the Master Plan had proposed. It was felt that; In the pre-literacy conditions of Africa, the school does not define the community with clarity as it does in Europe.31 At the same time, the internationally very fashionable Neighbourhood Unit Planning was used to justify segregation; everybody had to have their own neighbourhood (Hirst, 1994:108). Fig.3.9 1948 Nairobi Central Area, Source: Adopted from Thornton White et al. 1948. 31 The conflicting arguments for the expansion of schools and the proposal for neighbourhood units brings to fore a common trait of contradiction in the colonial logic. See for example; Myers, 2003; Mitchell, 1991; Berman, 1990. 76 In the early 1940s, the population of Nairobi was expanding rapidly because “landless” people were being shaken out of the Rift Valley and Central provinces by increasingly profitable agricultural production using mechanisation and farm chemicals as opposed to hand labour. This influx of people in Nairobi increased the demand for working class housing. At this time workers accommodation was calculated in “bed-spaces”. These bed-spaces were increased by over 30,000 between 1946 and 1957, but there was still a shortfall of 22,000.32 So in the period of prosperity and expansion in the city’s history, most Africans saw blocked aspirations and frustrations of legitimate demands within the system (Hirst, 1994:110). 32 In this regard, Turner argues that; it is what housing does for people that matters more than what it is or what it looks. It therefore would follow that ; it is illogical to state housing problems in the modern convention of “deficits” of units to some material standard (Turner, 1976). 77 Fig.3.10 Typical Layout – Neighbourhood Unit Source: Adopted from Thornton White et al. 1948 Nairobi was granted the City Charter on 13.03.1950, with great ceremony, the Duke of Gloucester handed the charter to the mayor, Alderman Woodley (Hirst, 1994:111; Anderson in Burton, 2002:138). Subsequently Nairobi accelerated the expensive provision of minority amenities. A new Racecourse, under the Jockey Club of Kenya was built. The National Theatre, the first National Theatre in the commonwealth, was also 78 built. It was the first part of a cultural centre where people of high culture and position could meet, in a well-to-do Nairobi (Hirst, 1994:112). Simultaneously, there weren’t enough houses or jobs within the city, so people created their own jobs, for example hawking. During this period, European attitudes to African housing were inevitably driven by considerations of economy, which were all too often unrealistic. G. A. Atkinson, a civil Engineer and advisor to the Colonial Office, noted the views of the European community when he visited Kenya in 1953 to make a study of Nairobi’s housing schemes. Too much hope is put on a new method of building to produce a “cheap house” he commented; There is no magic material which will build the perfect, permanent house for only a few pounds, though quite a few people in East Africa still seem to believe there is (Anderson in Burton, 2002:149).33 Despite all the planning, Nairobi was on the decline and was quickly becoming a “selfhelp-city” for the vast majority who operated an urban subsistence economy. In response, the authorities put in place even more social control and repression, which caused more illegal activity and inevitably crime (Hirst, 1994:113). The inability for Europeans to formulate any social compromise made real conflict inevitable. The contradiction at the centre of colonial hegemony was coming to a head. The measure of inconsistency Sir Andrew Cohen wrote between the Dominion and the Trusteeship policies remained unresolved, and time was running out. The dual policy of separate development would no longer work and coming down firmly on both sides of the fence, at the same time (Hirst, 1994:119). This polarised situation led to a clear change in civic housing policy in 1957. It changed towards providing family accommodation instead of single rooms and bed-spaces. Africans were now to be encouraged to own houses often self-built on prescribed lines for the emerging “better off” workers. While Apartheid was being established in South Africa, the British had decided to “go with” Africans who had a Western education in Kenya. It was a time of difficult compromises as the state of emergency had earlier been declared in 1952. At the same 33 This attitude still persists today; many a politician and bureaucrats quite often blame professionals for not developing low cost housing, when the actual problem is the management of the country’s resources. 79 time the establishment of Apartheid was important, as South African influences had been very strong in Nairobi’s development. Civic housing spurted with new estates, but unauthorised housing boomed even faster in the self-help-city. The professionals at the time, many of them new in their jobs could only hold on to the guidelines of the Master Plan. In the city’s history, 25,000 people crowded into Eastlands in 1960 alone, with perhaps a total of 50,000 in Nairobi extra provincial district, causing serious overcrowding resulting in increased crime, illegal hawking, street trading and illegal brewing. As the “unregistered jobs” were created so “unauthorised shelters” were built on a grand scale.34 While African housing was advanced on a tight budget, and within parameters thought appropriate to the apparently limited requirements of the emerging African urban working class, government resources were lavished on creating the image of a European “city in the sun” in the hope of attracting international corporate investment. At the same time corruption in municipal government was part of Nairobi’s colonial legacy that had skewed the development of the city through policies of segregation, rating and differential investment, but it also generated in Nairobi’s African citizens a deep scepticism about the capacity of government to effectively regulate the urban environment. In the shanties of Kaburini, Muoroumi, Mathare, Pumwani and Kibera, Nairobi’s “self-help-city” took shape in the 1960s in defiance of government, resisting control and regulation (Anderson in Burton, 2002:154). By the eve of independence, in 1963, the Nairobi cityscape was already characterised not by “model” housing estates, but by burgeoning shanties, whose poverty and squalor stood as testament to the historic inadequacies of colonial municipal government (Anderson in Burton, 2002:140). The city faced independence in a crisis (Hirst, 1994:129). The city’s social problems were temporarily eased politically, on attainment of independence in 1963. 34 As was shown in chapter 2, it can be argued that these activities were illegal in the eyes of the colonial regime, but pretty much legitimate to the actors in these activities. 80 Post Colonial Nairobi Overall Urban Process At Kenya’s independence in 1963 the new African government opted for a policy of continuity rather than change. Although the state continued to attempt to control internal migration, it was unable to enforce restriction over African mobility with the ruthlessness of its colonial predecessor (Burton, 2002:22). In addition, the institutional structures left behind by colonial rule and initially little modified by the newly independent government proved so ineffective in managing urban change. The post-colonial city experienced two particularly significant changes in its character, which can be attributed to mass urbanisation in the post-colonial period. The first of these was a dramatic alteration in the gender balance of Nairobi’s population. The male to female ratio during the colonial period was as high as 4-8 males to 1 female. This decreased in the post-colonial period to a Kenyan national rate of approximately 1.38 male to 1 female in 1969 (Burton, 2002:24) and 1.17 to 1 for Nairobi in 1999(GOK-CBS, 2001).35 The second phenomenon associated with mass urbanisation that transformed the urban landscape of Nairobi after independence was the informalisation of the city, which resulted in many informal settlements springing up. Such informal settlements (as well as informal economic activity) have commonly been associated with the urban poor. However, the informalisation of Nairobi was a process which by the 1980s, if not earlier, had encompassed urban residents from all social strata (Burton, 2002:25). Political and urban history are closely intertwined; for major internal political changes must always be presumed to have had an impact upon patterns of urbanisation. The attainment of independence was a major political change, which led to the expansion of the Nairobi city area.36 The city boundary was extended to include the Nairobi National Park to the southwest, some peri-urban residential suburbs like Karen and Langata to the southwest, Dagoretti to the west, Spring Valley to the north and a large extent of farmland suitable for future development to the east (Nevanlinna, 1996; Hirst, 1994; Morgan, 1970). With the extension, the area of the city grew to 684Km², with some 35 This gender balance increased the demand for family housing, in addition to forcing many families to live in single rooms. 36 This decision was basically spatially motivated. 81 342,764 inhabitants. In some sixty years, Nairobi had grown from a town of 18Km² in 1900, with a population of about 10,000 people, to a metropolis of thirty-eight times its area and more than thirty-two times its population. Table1 shows Nairobi’s demographic and spatial transformation over the 99 year period, while the new enlarged city area is illustrated in Fig.3.11. This enlarged area meant hundreds of miles of metalled roads, power and water supplies-unequalled anywhere else in East Africa (Hirst, 1994:138). Table 1: Nairobi's Area and Population 37 Year Area in (Sq Km) 1900 18 1906 Population 11,512 1919 25 1926 84 29,864 1936 49,600 1944 108,900 1948 91 1962 1963 118,900 266,795 684 342,764 1969 509,286 1979 827,775 1989 693 1,324,570 1999 696 2,143,254 Source: Halliman and Morgan, 1967; Kenya Population Census, 1962, 1969, 1979, 1989, 1999 37 This table brings to fore, the centrality of space on the urban process of Nairobi. Population and urban growth have a direct impact on the spatiality of the urban area. 82 Fig.3.11 Nairobi City Area, 1964, Source: Adopted from Hirst, 1994:138/139 From the colonialists, Nairobi also inherited a multicultural society in which privileges had been unevenly divided. Halliman and Morgan indicated the discrepancies in residential densities and population densities between the different parts of the city as shown in Table 2. In terms of racial composition, 71% of the Africans lived in Eastlands, 68% of Asians lived in Parklands and Eastleigh while 82% of Europeans lived in Upper Nairobi. On attainment of independence, the classification of residential areas based on race i.e. European, Asian and African changed to a classification based on income/social status i.e. High-income, Middle-income and Low-income. Geographically, Upper Nairobi is on higher ground over 5,500Ft above sea level and has well-draining red coffee soils. Eastlands on the other hand is on flat terrain about 5,200Ft above sea level, with poorly draining black cotton soils (Morgan, 1970; Thornton White et al, 1948). 83 Table 2: Residential and Population Densities ( Based on 1962 Census Survey )38 Location Residential Density Population Density (Dwellings/Acre) (Persons/Acre) 26 125.9 8.46 47 Eastleigh 4.47 47 Upper Nairobi 1.15 6 Eastlands Nairobi South Parklands and Source: Adopted From Nevanlinna, 1996:205 In addition to the foregoing, there were problems the Master Plan never dreamt of, or gave a technically impartial treatment. For example, Nairobi inherited a racially divided school system, with widely unequal facilities. They were quickly converted to A, B and C schools-open to all.39 At that time many African middle-class parents, were able to get a car before a “good house”, and therefore ferried children to school across the city (Hirst, 1994:138). This practice of ferrying children to school across the city is still prevalent today, and is one of the reasons why Nairobi experiences traffic jams. Fig.3.12 shows a typical morning traffic jam in Nairobi as in March 2005. 38 The current population densities in the various Nairobi residential areas closely follow this 1962 profile. Although all the three school categories were open to all, not all people could afford the fees in the various categories. This state of affairs, further entrenched segregation on economic lines. 39 84 Fig.3.12 Traffic Jam on Haile Selassie Avenue, March 2005 After the initial teething problems and the political excitements about “UHURU”, the economic realities of city life started to reassert themselves in painful choices. It was now time for the new African ruling elite to deliver urban goods and services to the residents of Nairobi. It is a well known fact that the priorities in even the most heterogeneous of cities have to be decided by somebody. This is how in 1965 UN experts said that Nairobi would need 26,300 new housing units by 1970. The Bloomberg and Abrams report (1965), reiterated the position of previous colonial reports of the 1950s, which had shown that housing for Africans was inadequate and insufficient (Syagga, 2002:86). After this report, a project team for implementing the report’s recommendations was set-up at the city Hall. This team produced 5,000 new, good quality houses in the five year period up to 1970. After this five year period, it became quite clear that conventional housing schemes could not do the job (Hirst, 1994:140). The transformation to a truly urban population was going slowly. Most people were living a dual culture, with strong connections to a rural homestead. This is what John 85 Lonsdale refers to as “straddling”. They hope to invest their urban income in improving, or at least saving, their farm lands “back-home” (Hirst, 1994; Lonsdale in Burton, 2002). This transient phenomenon of the majority of Nairobians could have hastened the proliferation of informal settlements in post-colonial Nairobi. Empirical data shows that as early as 1964, in addition to Mathare Valley and Dagoretti, there were 49 other settlements in the city, built without official permission and services. This number had risen to 199 by 2002 (Hirst, 1994:141; Weru, 2004). Another reason why transience persists could be the representation of Kenyan urban centres as places where people do not strike roots. White, Robertson and Lonsdale have demonstrated that these representations are gendered. A dominant discourse has emerged on the relationship between town and countryside in Kenya, where “town” has been equated with “women”, idleness and immorality, and “countryside” has been equated with “men”, hard work, honour and morality (Frederiksen in Burton, 2002:234). The S. M. Otieno case in the early 1980s also brought to fore the chronic tension between urbanism and tradition in Kenya (Atieno-Odhiambo, 1992).40 In 1971, it was estimated that one third of Nairobi’s population i.e.167, 000 people were living in unauthorised housing and were creating 50,000 jobs, and many worked in the formal sector in the lower-income group (Hirst, 1994:144). At that time, the policy towards this unauthorised housing was demolition; resettlement was not a city priority. The policy even intensified in 1970, as it turned out to be very useful for the new class of landlords, while the city’s policy with regard to housing was the provision of fully built units. The new council houses continued to be the more expensive ones, built for tenantpurchase but sub-let on a large scale, creating capital assets for landlords from public funds, but paid off by new tenants (Hirst, 1994:148). Examples of these schemes include, Uhuru and New Pumwani (California). Although these schemes were not really successful, the National Housing Corporation still uses this 1960s model of housing 40 S. M. Otieno a prominent Nairobi lawyer died and was forced to be buried in his ancestral home in Nyanza. This was against the wishes of his urban wife, Wambui Otieno, who wanted him buried at their home at Upper Matasia on the outskirts of Nairobi. The ensuing court battle was settled in favour of the rural clan, who argued that the Nairobi “home” was a mere “house” and that the real home was in Nyalgunga-Nyanza. 86 procurement. They have recently completed new tenant purchase houses in the Pumwani area, (see Fig.3.13). It was increasingly clear that no conventional housing schemes, such as the city departments were equipped to deal with could meet the demand for very low-cost houses. Fig.3.13 NHC’s Tenant Purchase Housing – Pumwani – April 2005 NGOs were increasingly getting involved in human settlement issues during this period, and were introducing new ideas; these new ideas had to be looked at. These included: self-built principle; core house projects; site-and-service schemes; site-and-phased-inservice projects etc. (Hirst, 1994:148). During the same period, as house prices and rents rose, many people were forced out of formal housing, into the informal housing of mud and wattle houses. Some became owner occupied, but the majority were increasingly built for rent. As a result, the so-called “squatter” settlements are in fact private developments often by entrepreneurs, outside the legal frameworks, indicating the failure of the official system in meeting the people’s needs. 87 After independence, the informal sector which had always been there, started to make itself felt in the economy. For example, the monopoly franchise for the city transport held by Kenya Bus Services Ltd (KBS), could not cope with the post 1963 demand for public transport at affordable cost, so private taxis came on the scene. In the early 60s, approximately 400 illegal vehicles charged a standard fare, “Mang’otore Matatu”, i.e. 30cents from the residential areas into town, often pursued by the police. In 1973, after 10 years of independence, the “Matatus” were legalised and their numbers multiplied. The demand for transport continued to increase, and by 1992, there were about 2,000 Matatus in Nairobi. They were creating jobs mostly for drivers and conductors (Hirst, 1994). Currently Matatu transport is the most common mode of transport, not only in Nairobi but in the whole of Kenya. Fig.3.14 shows Matatus in a Nairobi street. Fig.3.14 Matatu Public Transport - Ronald Ngala/Mfangano Streets – April 2005 Because of the many developmental problems facing the city of Nairobi in the late 60s, the Nairobi Urban Study Group (NUSG) was established in 1970. It was to plan a co- 88 ordinated growth strategy for the city until the year 2000. It reported in 1973, through the publication of the Metropolitan Growth Strategy (MGS). Like the Master Plan of 1948, the MGS continued the liberal ideology that dominated the Master Plan. The politicians assign technicians to plan, so that the plan can be characterised as politically neutral (Emig and Ismail, 1980:80). The MGS was a tool for state intervention, which supported the interests of the hegemonic class alliance of the local bourgeoisie and the Multi National Corporations (MNCs). The interests of the urban majority were neglected, in a similar way as the three preceding colonial plans. Segregation was used based on economic and class lines as opposed to racial and class lines. The MGS formed the basis for an application for World Bank assistance in the housing sector. This resulted in the city council’s Dandora project which started in 1975. There were to be 6,000 serviced sites in this project, targeting the very-low and low-income groups. However, the target group was never really reached; somehow the low-income groups got squeezed out, as 70% of them became tenants (Hirst, 1994:152; Discussion with City Director of Housing on 26.04.05). Today, the single-storey dwelling units are being converted into multi-storey mixed use developments, putting pressure on the infrastructural services. Fig.3.15 shows some of the transformations taking place in Dandora. 89 Fig.3.15 Transformations in Dandora - April 2005 Since 1978, there has been very little council intervention in the provision of urban services. This has been exacerbated by the neo-liberal theories of 1980s of less state intervention and affordability-cost recovery-replicability formula. What has been happening in Nairobi in recent times is the emergence of an informal modernism, particularly in Nairobi’s Eastlands. Moneyed Nairobians have found a lucrative niche in the low-income bracket, where they are building mixed use rental commercial high rise blocks for the urban poor Fig.3.16. This exploitative rental housing and poor transport have alienated many Nairobi citizens, who are beginning to question the whole “idea” of the city, and whether it is even sustainable (Hirst, 1994:167). In addition to this informal modernism, there has been a proliferation of informal settlements, as mentioned earlier. There is no data on who actually owns these settlements (slums).41 Some land on which people are squatting is actually privately owned, but the majority is government land. 41 Urban property is shrouded in secrecy, which in turn propagates corrupt practices. See chapter 2, Re-conceptualising urbanity in developing countries. 90 Evidence however shows that in the Nairobi situation, there are no squatters as such; rather there are illegal landlords who are collecting rent from illegal tenants (Hirst, 1994:171). Fig.3.16, Informal Modernism – Block 10, Embakasi Feb 2005 Production and Consumption of Urban Space The main variable that determines how an area urbanises is how space is produced and consumed (Rossi, 1982; Castells, 1983). In the colonial period, the public sector (colonial regime) was the sole producer of urban space, where the most striking aspect was the logic of partitioning urban space into two zones. The “European zone” and the “Indigenous zone”, in the case of Nairobi, there was a third “Asian zone”. This partition was done, not through any dialogue or consensus, but wholly on the whims of the colonising power, which made the colonial city heterogeneous and segregated. In the post-colonial period, Nairobi’s urban form and for that matter its production and consumption remained basically colonial. However, post-colonial Nairobi has 91 increasingly experienced a mismatch between the needs of the ever increasing population and the provision of public services and infrastructure. Urban management systems are generally unable to keep pace with infrastructure needs and in some cases have all but collapsed (Rakodi, 1997:560). Fig.3.17 shows the Nairobi Central Matatu terminus; an example of collapsed infrastructure services. Because of the mismatch in demand and supply of urban services, the informal sector has increasingly become the main producer and consumer of urban space. The discussion on informal production and consumption of urban space in Nairobi is at the core of this thesis. Fig.3.17, Matatu Terminal - Central Bus station. April 2005 Over the years, post-colonial Nairobi has evolved from an overly regulated city which reflected the needs of the erstwhile colonial powers to control African urban life in every possible way, we are now witnessing the birth of a new city form which reflects the new African reality of limited resources. What could be called the “self-help city” in the 1970s could as well be called the “informal city” in the 1990s. Another characteristic of 92 post-colonial Nairobi is the high level of poverty among its population. According to the Global Report on Human Settlements 2001; While urban poverty exists and is indeed growing in all cities of the world, it characterises aspects of the rapidly growing cities in developing countries (UNCHS, 2001). Thus the urbanisation of poverty is one of the most challenging problems facing the world today and Nairobi at the local level. These high levels of poverty are having a major impact on the production and consumption of urban space. Urban space is predominantly being produced informally, as can be seen in Fig.3.18 depicting some images of informal Nairobi. Fig.3.18, Informal Nairobi. February 2005 I argue that the process of urbanisation generally involves the concentration of people in one place, which then generates a need for the production and consumption of space. In the ensuing process, several variables come into play some of which are: - Who are the main actors in this process-individuals, builders, financiers, public sector, private sector etc.; What/how are the legal structures supporting these processes; How are design issues with regard to-density, set backs/height restrictions, aesthetics, technology and use of materials, infrastructure and carrying capacities etc. determined and by who? All these variables play a role in determining the urban space produced, which to a large degree determines the city form. In the colonial period and the immediate post-colonial period, the main actor in the production of urban space was the government (public sector), and as discussed earlier, the general public and the private sector who were the consumers of this product (urban space), played an insignificant role. 93 The planning proposals developed by the government for Nairobi, could not capture the speed and direction of growth in the peripheral areas, and in any case, these proposals were almost never supported by the level of capital expenditure necessary to implement their infrastructural projections. This led to the emergence of the informal sector as a major player in the production and provision of urban goods and services. Unfortunately this sector, although filling the gap left by the state, tended to be filled by operators who were mostly driven by the profit motive, and quite often, did not act in the public interest. Fig.3.19 shows a single roomed rental commercial residential block, an example of how the rich are exploiting the urban poor, by developing compromised dwelling environments. Fig.3.19, High Rise Blocks, Mathare North. August 2004 One common feature of post-colonial African cities is that the governance and legal structures supporting the production of urban space are replicas of 19th/early 20th century structures in Britain, France and Portugal. In fact one of the most influential sources of colonial legislation was the British Town and Country Planning Act of 1932. This was 94 the source of urban planning legislation in Kenya, Tanzania and the Rhodesias and was also behind the Nigeria Town and Country Planning Ordinance, proclaimed in 1948 (UNCHS, 1996:98). The application of these laws inevitably created uneasiness in many urban settings. Myers, 2003:126 highlights the tension in the colonial city with regard to squatting, prostitution, slum clearance and police raids. He further illustrates how neo-colonial tendencies have dominated most post-colonial Africa, in particular there has been over reliance on foreign consultants in matters regarding urban space production. In socialist Zanzibar, Karume relied on consultants from the German Democratic Republic (GDR), while Jumbe relied on Italians. Kenya’s capitalist Kenyatta relied on the British as Malawi’s Banda relied on South Africans etc. In the case of Karume’s Zanzibar, colonial enframing strategies were re-packaged in socialist-dominated packages (Myers, 2003). Rakodi, 1997:38 on the other hand deplores the inherited British ideology of impartial officials guided by notions of technical rationality, advising elected councillors who viewed the exercise of power as a moral non-political activity, as this was inappropriate in a post-independence situation. With regard to urban management; Traditional economic variables of (land, labour and capital) have to be understood within the frameworks of urban economies. Organisation of city management should therefore have a significant economic and business orientation. This dimension has been lacking in the tendency to focus on the supply orientation of urban management (Rakodi, 1997:550). There have been major transformations in formally planned settlements of Nairobi during the post-colonial period. One of the reasons for this occurrence could be the impartiality of municipal officials towards urban change. For example, the USAID funded Umoja Housing Estate, built in the 1970s has succumbed to commercial interests, which have taken advantage of the land values and urban economics of Umoja. This estate has gradually been transformed, with high rise apartment blocks replacing the originally single storey structures. In a city like Nairobi, which lacks adequate serviced land, and has a high demand for affordable low-income housing, it does not make economic sense to have single-storey structures on the Umoja site. Fig.3.20 shows how Umoja estate has transformed over the years, as impartial council officers watch. 95 The above kinds of transformations are occurring because the law and official agencies have been trapped by early colonial and Roman law, which tilt towards protecting ownership (De Soto, 2001). This in effect creates a fertile ground for the proliferation of extralegal laws. The rapid transformation that has occurred in the last 30 years in Nairobi has revealed the failure of formal planning, as there has been a mismatch between the supply and demand for urban goods and services. Informal processes have therefore taken over formal processes by default. Umoja 1978 (part plan) Umoja 2003 (part plan) Fig.3.20, Transformations of Umoja To understand the resilience of informal urbanisation in Nairobi, one should not underestimate the limited role that urban planning has played in the last 30 years or so (Emig and Ismail, 1980; Hake, 1977; Abudho, 1991). Plans, programmes, strategies and decisions taken from the perspective of planning, have historically been tools to reinforce the processes of social and political exclusion. Planners oftentimes have just been pawns in the broader agendas of politicians. Friedman, 1988 in “Florentine New Towns” makes the above assertion quite clear, by demonstrating how politics dictated urban design in the late Middle Ages. Plans have often been posterior documents for foreign credit or political consensus building, as was seen by the MGS with regard to the World Bank loan for the construction of Dandora. Political decisions have preceded plans rather than the other way round. 96 In Nairobi the plans for a Railway Town, a Settler Capital, a Colonial Capital and even the Metropolitan Growth Strategy (MGS), were all political instruments for managing change.42 Planning within a political system of monopolistic power serves to reinforce hegemony rather than operate as regulatory framework. Many urban plans are limited, due to lack of a strategic vision, which renders their policies only reactive to urban conditions. In the past the government used housing policies for political co-optation rather than to resolve the pressing problem of providing dwellings to the increasing urban population (Castillo, 2000). In addition, urban planners’ conventional practice of ignoring informal developers and accepting their subordinate role to political agendas makes urban planning extremely difficult. This has increasingly left the production of space in the hands of informal developers. Planning, Regularisation and Upgrading Conventional wisdom that informal urbanisation is unplanned development has limited evidence in empirical studies. The reality is that most informal urbanisation involves a wide range of mechanisms and strategies that are implemented to create a form of physical planning. In Nairobi for example, many roadside entrepreneurs start of by staking space along the road with some mobile platform for the display of their wares. After sometime they erect a timber framework around the platform and cover it with polythene paper. Eventually they seal the sides of the framework with timber off-cuts, sheet metal or boarding and cover the roof with metal sheets. 43 In some instances they even connect electricity to their structures either officially or illegally. In this way they consolidate their operations and often claim legitimacy to the space they occupy. Fig.3.21 shows one of these roadside enterprises in its consolidated state with power connection. 42 These plans were basically instruments for the manipulation of space. A process made possible by abstracting and commoditising space as discussed in chapter 2, see also Lefebvre, 1979. 43 See Fig.4.7, in chapter 4. 97 Fig.3.21, Consolidated Enterprise – Block 10. Feb. 2005 Quite often, the structures which are built informally get formalised with time, through a process of regularisation. Regularisation is the procedure by which the state grants legal title to individual dwelling owners occupying space through informal means. In doing so, they expect the settlers will make their own improvements. Regularisation along with upgrading of services and infrastructure, are the two-pronged dominant strategies planners use to address informal urbanisation in Nairobi and other cities. Most research has shown that regularisation has been closely tied to political patronage, consensus building and party favours. This is very similar to what plans have been used for as discussed earlier. Quite often, many settlements can exist for years without getting services, if residents are unable to organise and use political pressure to satisfy basic services such as water, sewage, roads and electricity. From the beginning of the colonial period, official planning did not address the needs of the African majority in Nairobi, by assuming that they did not exist. In late colonial Nairobi, a period during which planning authorities began to address these needs, they were still unable to meet the demand for urban goods and services by the African 98 population. This led to the proliferation of “informal planning” which filled the gap created by official planning. After independence official planners continued to ignore the informal urban process, in fact informal settlements did not appear on official maps, yet on the ground they were a reality. The speed of informal urbanisation was just too fast for the formal processes to respond to. Planners are in a weak position because they are unable to compete with many unauthorised settlement entrepreneurs, because they are unable to apply sanctions against developers who promote land sales outside the law and because they are usually perceived as the body responsible for picking up the bill for servicing and legislation once the land has been alienated (Ward, 1984-quoted in Castillo, 2000:22). Planning as a professional practise has basically been confined to urban areas. According to Kenyan history of census taking, an area is classified as urban if it has a population of more than 2,000 inhabitants, and has a defined extent or boundaries (Nalo, 2002:4). Nairobi as the largest urban settlement in Kenya is also the epi-centre of informal urbanisation. With regard to informality, 30% of Nairobi’s population or 635,036 inhabitants, based on the 1999 census figures live in Nairobi’s informal settlements. The Nairobi Informal Settlements Coordination Committee (NISCC), 1997 reckons that 55% of Nairobians live in informal settlements, while Syaaga, 2002 argues that the consensus is that 55-60% of Nairobians live in informal settlements.44 Whatever the figure, the main issue is that the number of people living in informal settlements is substantial, even at the current population of over three million people; we would still be talking about one million people living in these settlements. The planning of Nairobi can not afford to ignore this size of population, which contributes to Nairobi’s economy even if insignificantly. In Nairobi the security of tenure is closely linked to planning issues, authorities do not formally recognise informal settlements because the land on which they stand is not in a “planned” area i.e. was not set aside by the planning authorities as a residential area (Nalo, 2002). Planning is therefore part and parcel of the regularisation/upgrading 44 If 60% of Nairobians live in informal settlements, and assuming that 50% of the remaining population participates in the informal process, then about 80% of Nairobi’s population in one way or another plays a role in the informal urban process. Refer to Fig.2.1. 99 process of informal settlements. From 1963 until the late 1970s the attitude towards informal settlements (like in many Third World Countries) was to demolish them.45 Subsequently there was a trend towards tacit acceptance of these settlements, which led to their rapid growth. At this time the authorities adopted a laissez faire approach, of tolerating these settlements, generally not undertaking demolitions but not initiating any improvements either (NISCC,1997). A major departure to the above scenario however occurred in 1990, when two large settlements, Mouroto and Kibagare, were razed down by the city authorities, and an estimated 30,000 people were displaced (NISCC, 1997; Hirst, 1994). One characteristic feature of informal settlements is that the physical layouts are relatively haphazard, making it difficult to introduce infrastructural services. Quite often, urban services are non-existent or minimal, water may be provided to a few standpipes, if it is provided at all. Most residents do not have access to adequate sanitation, education and health services are also inadequate, although some NGOs and CBOs make significant contributions in this area (NISCC, 1997:2). The majority of house owners have some type of quasi-legal tenure through Temporary Occupation Licences (TOL) or letters from Chiefs where structures are on public land or agreements with land-owners when structures are on private land. In Nairobi therefore there is very little true “squatting”. However, in some settlements there is no form of tenure and residents have no rights (NISCC, 1997). The majority of residents are renters and most structures are let on a room-by-room basis with most households occupying a single room or part of it. It is worth noting that although many residents of informal settlements have jobs in the formal sector; the majority earn their living in the informal economic sector, in small businesses ranging from hawking to service and production enterprises. Of the approximately 40,000 small businesses in Nairobi the great majority are in informal settlements. In other words, informal settlements are an integral part of the city economy yet, in terms of services, place few demands upon it (NISCC, 1997:2). In some settlements such as Kangemi, Kawangware and Githurai (which were originally part of rural Kiambu), there is individual freehold tenure. In these settlements land owners have more incentive to invest and to work jointly with others in improving services. In these 45 See chapter 2 – Settlement Demolition Policies 100 “private” settlements the proportion of absentee landlords is much less than those on public land. The majority of settlements are on public land, either held directly by the central government or vested on leasehold to the Nairobi city council and/or public corporations. These settlements normally have higher densities and worse conditions, sometimes much more than those in privately held land. An attempt to regularise and upgrade, Mathare Valley one of the settlements on public land hit a snag due to conflicting interests of structure owners (Slumlords) and tenants. Fig.3.22 shows some images of Mathare 4A, started in the mid 1990s but has since stalled. The Mathare 4A upgrading project was supported by the German NGO GTZ. Fig.3.22, Images of Mathare 4A. August 2004 Many other NGOs/CBOs have also been involved in upgrading projects in various informal settlements. One example is the upgrading project by Pamoja Trust, in the Huruma area of Nairobi. This project involved the demolition of temporary structures on a 30Mx36M plot. The plot has then been built with 34No. Multi-storey family units with a total of 54M² spread on three levels with 18M² on each level. The uniqueness of this project is that most of the building materials were prefabricated on site. Fig.3.23 illustrates the outcome of this Huruma project as at April 2005. Whereas the intervention of NGOs/CBOs by way of upgrading settlements is welcome, the efforts are not well-coordinated. They are also very small in scale, and spread over many settlements, making their impact on improving the residents’ standards of living insignificant. What is actually required is to mobilise adequate resources, which can be used in upgrading a large enough settlement, which can be replicated over time. On this 101 regard the Huruma project offers a useful intervention strategy, if it can be implemented on a large scale. Fig.3.23, Three Dimensional Upgrading, Huruma. April 2004 In settlements on public land, plots have been allocated in a number of ways by officials to individuals. In some instances a plot is allocated with a Temporary Occupation Licence (TOL) by the local authority, which allows a temporary building to be constructed. Quite often, buildings of the lowest possible standards remain standing for many years. Most are barrack type blocks let to tenants by absentee landlords. These constructions are quite similar to 1921 colonial bachelor quarters at Kariokor, earlier discussed in this chapter. Allocation of plots is also undertaken by Chiefs (Local Administration Officials) by means of a letter or verbally (NISCC, 1997:3). Empirical evidence shows that the Chief’s allocation is done in conjunction with the Village Chairman at a consideration of 5,000 shillings per room to be built. None of these practices/processes accords with the provisions of Kenyan land law but they have been practised with little challenge for many years. Clearly such a system of allocation, 102 informal but officially sanctioned, provides benefits to some officials and underpins a system of patronage (NISCC, 1997:3). The results of this system are mainly negative. Profits accrue largely to absentee land/slumlords, haphazard layouts prevent the introduction of services and densities/overcrowding seriously endanger the health of inhabitants. It must however be remembered that these settlements do provide cheap accommodation which the poor can afford, something which the formal sector, be it public or private, has been unable to achieve. These subdivisions and allocations result in the many informal settlements dotting the city landscape (Fig.3.24). It is these settlements that are the subject of regularisation and upgrading. Fig.3.24, Partial Layout, Typical Informal Settlement 103 It should also be noted that; Nairobi as a city will simply be unable to achieve its full potential as a worthy capital and engine of the nation’s growth if the majority of its citizens are unable to achieve their own potential. NISCC argues that security of tenure is fundamental in unblocking the potential of residents of informal settlements to use their own resources to achieve development. Informal settlements should therefore be regularised and formally integrated into the physical and economic framework of the city. In trying to integrate some of these settlements within the city, Zimmerman an informal settlement to northeast of Nairobi, was recently, given a blanket approval to be a formal settlement. Although it is hoped that some owners may take advantage of their newly acquired title deeds as a result of formalisation, evidence has shown that they may not improve the physical environment of the settlement, not to mention the construction of infrastructural services. 104 4. DIVERSE INFORMALITIES Introduction In chapter three the discussion on the urban history of Nairobi, revealed how formal planning strategies adapted from the colonial period had failed in the post-colonial period. The failure of these strategies, which were designed to contain settlement rather than suggest growth, created the conditions for informal urban processes to proliferate and to fill the void left by formal planning. The emergent informal processes ranged from those of the poor on the one hand to those of the affluent on the other, with the survivalist being the most purely informal and the affluent being the least informal (see Fig.2.1). These informal processes are in principal extralegal practises, which are undertaken because of the failures of the formal process to provide the necessary commercial and residential needs of the population. They manipulate and take advantage of the weaknesses of the legal framework, and range from entirely illegal on the one end to those that in small ways add on to or redesign legal/physical structures. These practices are not homogeneous as generally discussed in most literature on informality; they are heterogeneous and are also not the preserve of the urban poor. Evidence in Nairobi has shown that informal practices which I will refer to as “Diverse Informalities” are practiced by all socio-economic groups of the Nairobi population. These informalities are classed informal because they are not fully formal, although they may have certain aspects of formality within their structure. For examples hawkers may operate with or without a licence, and even if they are licensed, they are not taxed and are therefore not fully formal. Similarly many informal settlements have some official recognition, usually by way of temporary occupation licenses. But the plots on which they are built have not been subdivided formally, and the buildings built have no formal approval. These varying degrees of the legal status of the businesses/settlements contribute to the diversity of the informalities. Over and above the legal status of the informalities, the physical/spatial dimension these informalities acquire is a central concern for this thesis. Survivalist informalities are to a large extent mobile or transient, and therefore are not fixed to a specific location. On the other hand primary informalities, dominated by informal settlements are characterised by the subdivision of land and the construction of buildings 105 informally. Intermediate informalities are characterised by the informal construction of new settlements and the transformations of existing settlements. Like intermediate informalities, affluent informalities are also characterised by the construction of new settlements and the transformation of existing ones. However this category is dominated by people from the high income group/affluent members of society. The very low income groups adopt survivalist strategies, while the low and some middle income groups engage in primary informal practices. The middle income group on the other hand practice intermediate informalities as the high income group engages in affluent practices. The separation of these informalities provides a more nuanced and accurate description of the informal urban process in Nairobi. The categorisation is not absolute as the boundaries are seamless, with certain characteristics shared by all the forms of informality and others unique to one or the other form of informal practice. The different informalities, impact differently on the urban fabric and infrastructure, with both the survivalist and affluent having the least impact, whereas the primary and intermediate categories have the most impact. The categorisation is basically a study tool in reconceptualising informal urbanisation. At their core, what I have called “Diverse Informalities” shared a number of characteristics. Common Traits in these Informalities • Diverse informalities have their basis on individual effort, which results in sole proprietorship. These practices are therefore not subject to lengthy bureaucratic decision making processes, which mean that failure and success are borne individually. • Diverse informalities are small enterprises; depending on circumstances, the sole proprietor may hire additional hands in order to achieve her/his goals. This additional assistance rarely exceeds 4-5 people, meaning that the operations remain small scale (small enterprises). • Diverse informalities fill the void left by the failure of the formal urban process, in other words they are a default urban strategy. • Diverse informalities produce products of extremely varied standard and high use value i.e. they are flexible and utilitarian. 106 • Diverse informalities grow progressively through accretion or addition, as opposed to complete packages. What follows, are descriptions and examples about what makes each of these informalities different. To begin with, Fig.3 below highlights the salient attributes of each category of informality, and then the detailed analysis of each category will follow. Table 3. Categories and Salient attributes of Diverse Informalities. Category Survivalist Primary Intermediate Affluent Type of No tenure since it is Letter of Allocation, Secure Tenure Secure Tenure Tenure Mobile/transient or Temporal Occupat- Normally Leasehold Absolute or Lease- ion License (TOL) For 99 Years hold for 99 Years Characte- Transient in nature Place based and Settlement based, Settlement based, ristics with a bias to Complex. focusing on biased to residential Commerce and Dominated by Low residential and few developments. dominated by the and Middle Income commercial activities. Dominated by high urban poor. Groups. Dominated by Middle income groups. May operate with or Require license from Income and a few Commercial activities without License. not undertaken. council to operate. High Income players. Engage in residential Settlements can be and commercial new or extensions/ Activities. Modifications. Impact on Minimal impact Most prominent Has large variety of Generates all types Built Fabric on built fabric. physically and building types. of architectural impacts heavily on Uses standard styles-eclectic. the built fabric by approved materials. Little overall impact way of kiosks and Builds on labour on built fabric as they 107 settlements. contract at different are in low density Uses all sorts of times and locations. Zones. materials, s/hand and recycled. Impact on Prey on water, Infrastructure electricity and sanitation systems. Make legal or illegal Puts additional Takes advantage of connections to pressure on services. well serviced land. services. Builds services on Puts additional self-help basis. pressure on carrying Doubtful quality of capacity of services. design and constr. Costs Requires small sums Requires tens/ hund- Requires millions of Requires large sums of money to start up. reds of thousands. shillings to operate. of money. Pays minimal license Pays minimal fee to Pays statutory fees. Pays statutory fees. Remains statutorily Subject to demolitio- Development plans Lacks social ameni- Illegal ties, and travels long fee to the council. council. Pays protection fee to youths/police. Other ns with or without Notice. may be illegal. distances to access them. Source: Author Survivalist Informalities Survivalist informalities are not place specific; they are mostly transient in nature with a bias to commerce. From a legal perspective, they may or may not have a trade/operations license, and because they are not place bound, they have no land tenure, and therefore 108 irrespective of whatever form of legitimacy they may have, they remain statutorily illegal, as temporal licenses to not grant full legal status. These informalities require little start up capital, and are thereby dominated by the urban poor (very low income groups), although some low and middle income people may be players through proxies. Their land tenure and legal status, makes it impossible for them to access development funds from formal financial institutions. The most viable option of accessing funds is to borrow from their own small circle of peers, who may have formed a savings and credit society. This society can then lend small amounts of money, depending on individual shares, on a rotational basis.46 Survivalists are generally poor, which means they spend their productive time on subsistence activities and have little time left for collective group activities. This makes them vulnerable and politically weak, and therefore subject to political manipulation, underpinning a system of patronage. Since survivalist informalities are mostly transient, they have minimal impact on the urban built fabric. However, as they mostly operate in circulation corridors, they tend to congest these corridors thereby disrupting normal functions. With regard to infrastructural services, their tendency is to use water, electricity and sanitation systems through illegal connections, consequently denying the council much needed revenue. However, all said and done, irrespective of all the shortcomings of these informalities, they provide a means of an urban livelihood for the poor, even if marginal. The existing regulations of local authorities through by-laws and enforcement practices often restrict the economic efficiency with which the poor can pursue their trading, artisanal and other service provisions. These regulations are actually those designed by the colonial regime, but have remained intact even after the attainment of independence. Africans were not supposed to engage in other income generating activities other than in government employment, formal private sector employment or as domestic workers for Europeans (Bujra, 1975; Hake, 1977; Emig and Ismail, 1980; Burton, 2002).47 46 These arrangements are not integrated into the formal property system, and are not fungible (De Soto, 2001). 47 As discussed in chapter 3, a policy of continuity rather than change was adopted in the post-colonial period. 109 Today the urban poor have devised various strategies of survival, for example water vendors charge inflated rates of between Kshs 10 and 20 ($ 0.125-0.25) for a 20 litre jerrican, while those who operate community water points charge Kshs 2-5 for the same amount of water (Lamba, 1994; Mitullah and Kibwana, 1998). My own findings at Mukuru Kwa Njenga in March 2005 show that vendors sell a 20 litre jerrican of water for Kshs 3-5, which means that the cost of water has little changed in the last 10 years. There are several other income generating activities which the poor engage in, as they struggle to participate in the capitalist urban economy, literary living on their own “wits”.48 Some of these activities include; mobile street vending; vegetable vending commonly known as (mama mboga); maize roasting; handcart (mkokoteni) transport; shoe shining; roadside tree nurseries and flower ports; roadside blacksmithing; railway line petty trading etc. Those who operate within the Central Business District (CBD), tend to congest street pavements making it difficult for pedestrian movement. These street traders have been a source of conflict between the city authorities and formal shop owners, as they disrupt the normal operations of shops. Quite often the city inspectorate department carry out raids where vendors are arrested and their wares destroyed since many of these vendors do not have official permits to trade. Much as this scenario may look gloomy, these informalities however, create a means of survival for many who are otherwise unable to find space in the formal urban sector.49 Survivalist informalities have no land tenure, since they are generally not place based but transient. The most transient vendors carry their merchandise on their shoulders and move from place to place, soliciting for buyers. Such vendors, though found all over the city, are more dominant in residential neighbourhoods that are near the CBD, like Shauri Moyo, Eastleigh, and Nairobi West etc. Many Nairobians who live in these neighbourhoods buy from these vendors, which in turn perpetuates this kind of activity. Some transient vendors focus on motorists, and walk up and down the streets, particularly Uhuru Highway. Several motorists in the end do buy some of these wares, which are principally electronic/electrical products like mobile phones/chargers, aerials, extension cables etc. 48 See for example; Cooper, 1987; Burja, 1975 etc. As was discussed in chapter 2, a similar scenario prevailed in Paris for more than 300 years, and was only stopped by the French revolution. 49 110 Other survivalist informal operators occupy space on a daily temporal basis, where they set up shop in the morning and wind up at night fall. Vegetable vendors typically operate in this manner; Fig.4.1 illustrates such a vendor in the South B shopping centre. Here the vendor (mama mboga), places her vegetables which can include; cabbage, spinach, onions, tomatoes etc. on a low level wooden framework, and waits for the numerous passers-by to come and buy. Typically mama mboga’s operations at the outlet spot starts at around 10.00 hours, the early morning hours are spent on making wholesale purchases at Gikomba or Wakulima market near the CBD. During the day, the business is rather low, but peaks between 17.30 hours and 19.00 hours, the time when many people are going to their residences after their daily chores. Because of the low income levels, many residents make daily purchases, as weekly/monthly shopping is reserved for the few rich residents. Many people buy their vegetables from these vendors as there are no other vegetable selling points. The supermarkets and other council markets are too few and are far in-between, creating a void which if filled informally by the numerous mama mbogas. This category of “informalities” does not in general claim any user rights to the space they use, although some vendors may use space continuously until they are able to claim some user rights. The roadside Tree Nursery and Flower Pots vendor on Limuru Road Fig.4.2 and the Tree Nursery on the Jamhuri access road Fig.4.3 are examples of vendors who use the same space/place continuously. 111 Fig.4.1, Mama Mboga – South B Fig.4.2 Roadside Flower Pots Fig.4.3 Roadside Tree Nursery In this particular case, these vendors are operating on road reserves, which have remained undeveloped over many years. This brings to focus the issue of how big/wide road reserves should be, and how should they be maintained and by who? In a situation of limited resources and lack of job opportunities, undefined road reserves (see discussion on urban edge in chapter five), offer a good opportunity for the urban poor to 112 carry out their subsistence activities. Other operators who have taken advantage of undefined/undeveloped road/railway reserves are the Jua Kali blacksmiths at Landhies Road-Shauri Moyo Fig.4.4, Jua Kali shoe/clothes dealer at City Stadium Fig.4.5 and Petty traders along the railway line at Mutindwa-Buru Buru Fig.4.6. Fig.4.4 Blacksmiths Fig.4.5 Shoe/Clothes Vendor What is striking about this group of vendors is that they are consolidating their premises by building temporary structures to protect them and their products from the elements of the weather. These vendors make deliberate strategic spatial decisions in choosing the locations of their operations. The railway reserve vendors at Mutindwa-Buru Buru and at Laini Saba-Kibera are located on major pedestrian thoroughfares. Many residents in Umoja estate cross through Mutindwa on their way to and from the CBD, industrial area and other parts of Eastlands. Similarly the Laini Saba pedestrian thoroughfare is the main access to the eastern side of Kibera from the CBD and many other places outside of Kibera. In fact the main matatu terminus at Golf Course estate is located at the head of this thoroughfare. Survivalist vendors may start initially by occupying space and displaying their merchandise on temporary stands. This may evolve into the stands being enclosed by timber supports with polythene covering the top of the supports. Eventually, the timber supports can be improved to become screens/walls made of timber or metal sheets, while the polythene cover gets replaced with corrugated iron sheets. The original stone/timber stand can be replaced with timber worktops including the creation of lockable storage space. At this point the activity ceases to be survivalist, and graduates to the primary 113 category, as it now becomes firmly place based Fig.4.7. 50 The above scenario clearly shows that the strategies taken by this type of vendor are not social, political or legal but spatial, thereby emphasizing the centrality of space in the process. Fig.4.6 Mutindwa Petty Traders The maize Roaster in Mukuru kwa Njenga, shown in Fig.4.8 is likely to take the kind of trajectory described above, where the umbrella, will be replaced by a wooden framework and polythene roof cover, and eventually into a fully fledged kiosk. At that point the vendor could diversify into trading in other commodities, while the maize roasting can continue to be done on the outside. These are some of the survival strategies vendors adopt, which may take months or even years to accomplish. This is why places/spaces of informality undergo rapid transformations, such that informal space today, looks quite different than it looked a few years ago. Nearly all these vendors apart from the most transient pay some nominal fee to the council for their annual business licenses. Although these licenses give them some form of official recognition, they remain statutorily illegal. 50 See footnote 43. 114 Fig.4.7 Evolution of a Kiosk Survivalist informalities have minimal impact on the urban built fabric. Many vendors like mama mboga, operate under the sky in the hot sun (Jua Kali). Those who have built temporary structures like the blacksmiths at Shauri Moyo Fig.4.9 and the traders along the railway at Laini Saba-Kibera Fig.4.10, tend to concentrate/crowd in one place. The result is that, patches of these types of activities spread all over the city and thereby do have some minimal impact on the overall urban built fabric. Although the Jua Kali blacksmiths at Shauri Moyo make metal products like trunks, pails, water dispensers etc. they are unable to break out of the survivalist category. One of the reasons for this static scenario could be that; they are using archaic technology, which relies heavily on physical strength for hammering the metal into shape. The other is that; the premises on which these blacksmiths operate, has no secure tenure, making it inappropriate for them to invest in advanced fabrication technologies. Their products therefore remain sub-standard and are unable to fetch higher prices on the market. These conditions condemn the blacksmiths to the survivalist category of informality, as their investment is not “fungible” as De Soto would say. 115 Fig.4.8, Roadside Maize Roaster Fig.4.9, Shauri Moyo Blacksmiths Fig.4.10, Laini-Saba Traders There are other activities like the hardware dealers at South B, Fig.4.11, who although operating from the same place on a continuous basis, have not built any enclosure for their activities. They have only built wooden/metal stands on which they display their wares, otherwise like mama mboga; they also operate under the sky. 116 Fig.4.11, Assorted Hardware Dealers – South B Survival informalities impact on the infrastructural services negatively, since the many illegal connections made to water and electricity supplies, are liable to leakages and power surges. The council and the lighting company, also loose a lot of revenue through these illegal connections, as they are unable to charge vendors who have made such connections. The majority of operators, who are unable to make illegal connections for the supply of electricity can only, operate during the day. Often the premises for these activities become a security risk as they turn into havens of muggers and other criminals on nightfall. The lack of sanitary facilities also presents a major environmental problem. Quite often vendors create alliances with business people who have sanitary facilities in the neighbourhood, thereby gaining access to these facilities. In the event that such alliances are not possible, then the vendors just pollute the immediate surrounding area. The survivalist category is the easiest and cheapest category that can be accessed by the urban poor. It requires little money to start up business, with or without a license from the council. Some people from high income groups however, engage in business in this category though proxies for their own monetary gains. Players from high income groups buy merchandise in large quantities, which they then distribute to several hawkers who 117 sell them on the behalf of the absentee players. Often these hawkers who act as proxies are paid on commission basis depending on the sales turnover. The commissions paid are generally small, with the net effect that the absentee players are simply exploiting the unemployment situation of Nairobi. Primary Informalities Primary informalities are place specific and complex, and engage in both residential and commercial activities. Normally, being place based, they would have some form of land tenure however marginal, it may be in the form of an allocation letter from a government administrator or a Temporary Occupation Certificate (TOL) from the local authority.51 Unlike survivalist informalities which may or may not have a license, primary informalities generally must have trade/operations licenses, which they pay for annually. For one to operate in this category, it requires tens to hundreds of thousands of Kenya shillings to set up shop, meaning that this category is dominated by the low income group and some middle income people, who are able to raise such funds. Most low income operators would normally be resident, while middle income players would normally be absentee players, who rely on resident middle men for their transactions. This category of informalities tends to have strong peer group associations, where they are able to save money for lending to each other and for actualising any other common projects. They are however unable to access funds from formal financial institutions, because of their temporary land tenure situation, as Temporary Occupation Licenses do not qualify as collateral for lending purposes in these financial institutions.52 Primary informalities, being place based, have a major impact on the urban built fabric. For example, all the kiosks and informal settlements that dot the city landscape fall in this category including the numerous garment stalls (so called exhibitions) that have sprung up, mostly in the CBD. They create employment for many people, particularly local artisans (fundis), who get hired to construct the said kiosks, dwellings and stalls. These constructions utilise all sorts of materials ranging from polythene, timber boards, iron sheets, recycled drums etc. The lack of design input means that the resultant built fabric 51 52 See Table 3. For a discussion on peer group associations, see De Soto, 2001: 90. 118 is a collage of various typologies, whose architectural merits are doubtful. The kiosks are normally located on main circulation corridors or as adjuncts to houses in low and middle income residential areas. Dwellings in this category would be located on public or private land, after the structure owner has paid a fee to public administration officers or the private landlord. In some instances, structure owners invade public or private land and build their structures without any agreement.53 Most dwellings in this category are built for rental purposes, with the majority of the structure owners being absentee landlords. The temporariness of these informalities, forces the structure owners to pay protection fees to the police or political party youths, so as to give some form of protection from demolitions. These structures are normally subject to demolitions by the government or landlord, with or without notice. In some cases, settlements are known to have been burnt down in an effort to displace the settlers. It should however be noted that the temporary occupation license (TOL) issued by the city council gives more protection to structure owners, but such licenses are few, because the commissioner of lands controls the delineation of land and the city council has no control over his/her actions. The majority of structure owners therefore end up just getting letters of allocation from the local chief, which are subject to manipulation and abuse. Primary informalities may also have a negative impact on the city’s infrastructural services, as often they make legal or illegal connections to these services, putting additional pressure on the design carrying capacity of these services. Quite often, these connections increase; the frequency of water shortages, possibility of sewage blockages and overloading the power supply, leading to power cuts. The illegal connections also deny the relevant authorities much needed revenue. Most kiosks are also built on road reserves, and sometimes on top of drains, they therefore increase the occurrence of flooding during the rainy seasons of March-May and September-November of each year. The decisions of establishing and choosing the location of these activities are primarily socio-economic and spatial. Many operators may not be aware of any legal 53 See NISCC, 1997; Matrix Development Consultants, 1993 for a discussion on the establishment of informal settlements. 119 requirements in establishing their activities, and even if they may be aware, they would rather feign ignorance. Primary informalities form a major sector of the city economy, and create employment opportunities for many people who are unable to join the formal sector. This category also generates a regular income for the proprietors, who unfortunately are outside the formal tax brackets, and therefore do not pay any taxes on their income. Like their survivalist counterpart, primary informalities perpetuate a political system of patronage, since they require continuous protection from big men.54 Their individualised character of operations makes it difficult for them to organise themselves into a viable political force, and therefore remain perpetually marginalised. Market Stalls (Exhibitions) in the CBD Evidence shows that a typical exhibition in Nairobi’s CBD measures approximately 6mx30m, and houses about 30 stalls/sales benches. Each stall/sales bench occupies about 3m² and is manned by one or two sales persons. All the stall owners clean their work spaces on a regular basis, but the overall cleaning of the whole sales space is done by employees of the landlord. The license to operate the business is paid to the council by the landlady/lord, who also takes care of the security of the premises. The landlady is also responsible for the payment of water and electricity. Typically the premises are fitted with metal grilles to the street front, and watchmen are in addition hired for security during the night. Sanitation facilities at the back of the sales space are shared by all the 30 tenants. Each tenant pays Kshs 500 ($ 6.25) daily rental fees to the landlady; this fee is collected by the landlady’s agent who could also be one of the tenants. It is common for many stall owners to purchase their goods/merchandise from Dubai in the United Arab Emirates or one of the East Asia free ports, on a monthly basis. From an economic point of view, the landlady gets an income of Kshs 15,000 ($187.5) per day, which translates to Kshs 360,000 ($ 4,500) per month. This is more than three times the rental income the sales space would fetch were it to be let to a single tenant. It therefore makes economic sense to let out the space in the form of stalls/sales benches. In effect what is happening in Nairobi’s CBD is that; the external survivalist informality on 54 Chabal and Daloz, 1999 discuss the system of patronage in many African countries. 120 the streets is increasingly being internalised. The invasion of shoppers’ territories in the 1990s forced many shop owners to convert their shops into “exhibitions”, which in essence are internalised market places, Fig 4.12 and 4.13 are some examples of these stalls. The stalls create employment for many job seekers of Nairobi who would otherwise remain unemployed. The average pay for a sales person is between Kshs 100 and 150 ($ 1.25-1.875) per day, although some stall owners prefer to pay the sales people on commission basis. Typically they pay a negotiated commission on daily sales which average about Kshs 3,000 ($ 37.5). With these levels of daily income, the sales people can only afford to live in informal settlements, where the rents range from as low as Kshs.200 ($2.5) per month, for low quality rooms in Mukuru to over Kshs.1, 000 ($ 12.5) per month for higher quality rooms in Kibera (Syagga, 2002b). Fig.4.12, Interior Nairobi Stalls - Moi Ave. Fig.4.13 Stalls – Tom Mboya St. Alecky Fish and Food Kiosk Another primary informality arises from the many kiosks that dot Nairobi’s urban landscape. Alecky Fish and Food Kiosk which is located at the entrance of Imara Daima estate off Mombasa road is an example of this. The story of Adhiambo the proprietor of this kiosk is also an example of the many people who are responding to the effects of Structural Adjustment Programmes.55 Adhiambo who was in her late 30s, at the time of the survey, was previously employed by Kenya Extelecoms. She was retrenched in 1998, and with the golden handshake money, she received as her terminal dues, she opted to 55 See the discussion on SAPs in chapter 2, under Re-conceptualising Urbanity in Developing Countries. 121 venture into the fish and food business. The decision for this venture was purely socioeconomic, however in order to achieve her goal, she had to get some physical space, and hence the kiosk. She opened the outdoor fish vending business in year 2000, with the food kiosk opening in 2001. Adhiambo pays several annual license fees to the local authority in order to operate the business; these include a license from the Fisheries Department of Kshs 600 ($ 7.5), Food and butchery license of Kshs 10,000 ($ 125) plus a public health license of Kshs 1,200 ($ 15). There are no services provided by the council to the kiosk, and water has to be bought at a nearby vendor’s tap, which sells a 20 litre jerrican for Kshs 5 ($ 0.0625). There is also no sanitary provision and most customers have to rely on facilities at their work places (most customers come from nearby companies and estates). Pressure lamps are used for lighting in late evenings, although some adjacent kiosks have made illegal power connections from the adjacent Villa Franca estate. The 55 Kiosk owners at this location have made a welfare association, which hires watchmen who provide night time security.56 In terms of procurement of the kiosk, the area chief allocated the space (land) which is on a road reserve. Adhiambo bought the space from the first allottee at Kshs 20,000 ($ 250), and spent approximately another Kshs 30,000 ($ 375), building the kiosk using local artisans (fundis). Fig 4.14 shows the layout of the kiosks on this road reserve, while Fig. 4.15 shows images of Alecky Food and Fish Kiosk. The kiosk which opens seven days a week creates employment for 2 kitchen staff who get paid Kshs 120 ($ 1.5) each per day, and 2 food servers who are paid Kshs 100 ($ 1.25) each per day.57 In addition there is another assistant employed to man the outdoor fish stand. The sale of fried fish takes place in the evenings between 16hours and 19 hours. This business generates Kshs 6,000 ($75) per day from the sale of fish and Kshs 3,600 ($45) from the sale of food per day. This translates to Kshs 288,000 ($3,600) per month. Assuming the cost of purchases and other overheads are 90% of this amount, the net income is Kshs 28,800 ($360) per month or Kshs 960 ($ 12) per day. Running the outdoor fish stand alone would generate a net income of Kshs 18,000 ($ 2,250) per month 56 57 The formation of peer group associations is discussed by De Soto, 2001 and is covered in chapter 2. These employees are just on the borderline of the UN’s absolute poverty line of $ 1 per day. 122 or Kshs 600 ($ 7.5) per day. It was however observed that the business is not that rosy. During the rainy season; March to May and October to November, this area gets quite muddy when the black cotton earth road turns into a mud slurry, making it uncomfortable for people to walk and therefore unlikely to come to the kiosk. This is why I have deliberately used a 10% proportion for net income, in order to absorb the bad sales on muddy/rainy days. Ordinarily the net income should be in the range of 20-25% of total purchases and overheads. The risk of doing business during the rainy season means that Adhiambo must maximise on sunny days by modifying her price regime. In any case as in most economic transactions, where there is risk, there is a high rate of return (Syagga, 2002b: 37). The foregoing figures indicate a lucrative business by Nairobi standards, and may not qualify the proprietor as a low income earner. On this account, a previous study by Amis, 1994 revealed that a typical 10 room structure in an informal settlement gave an annual rental return of 131%. Accordingly Amis concluded that; It would seem quite possible that, as often suggested, unauthorised housing and matatus are the most lucrative investments in urban Kenya (Quoted in Syagga, 2002b:9). In terms of space, the kiosk occupies approximately 20m² and measures approximately 3mx7m. It is built of a timber framework with corrugated galvanised iron roofing sheets, with sheet metal used for walling. While the outdoor fish stand relies on the shed of the thorn tree for protection from the element of weather as can be seen in Fig.4.16. There are no special architectural merits embedded in the design of the kiosk, however in the context of the overall cluster of kiosks, an architectural collage is formed. This is because each kiosk has its own design with the result that the overall composition may not be harmonious as can be seen in Fig.4.17. The kiosks however are kept to the periphery of the road reserve, leaving the motor car carriageway free and uninterrupted. It is obvious that the motor car movement is privileged over other forms of mobility including walking.58 58 See Samuels, I. et al. 2004: 174 for a discussion on the role of the car in residential areas. 123 Fig.4.14, Kiosks on Road Reserve (Centre of image) Fig.4.15 Exterior and Interior, Alecky Food Kiosk 124 The design of kiosks is an issue in which the local authority can intervene by providing standard type plans. In this regard Coca Cola bottling company has developed a standard “coca cola” kiosk, which is distributed to vendors, this example shows that it is possible to intervene with standardised kiosks at city level. However since the authorities consider these informal business outlets as illegal, and officially do not exist, they do not make any effort in intervening. For this reason people continue to build using whatever materials they can get and at a price they can afford.59 Fig.4.16 Outdoor Fish Stand. Fig.4.17 A collage of Kiosks The lack of employment opportunities in the city which has led to informal trading is manifested in the form of haphazardly distributed kiosks, some of which are licensed by the city council while the majority trade without valid license. In fact Kiosks’ Allocation and haphazard hawking have no planning component, since no clear policy exists within the council. Planning of these activities could provide employment for a large number of people who earn their living from hawking (Syagga, 2002:42). Although there may appear to be no planning in these informalities, informal operators make deliberate decisions in the choice of location, they often tend to concentrate in areas with large pedestrian movements. These spatial preferences, is a lesson that the formal planners and local authorities can learn from these informal entrepreneurs. 59 See chapter 3 – post-colonial Nairobi. 125 Hollywood Garage “Hollywood Garage” a Jua Kali (Hot Sun) garage also operating at the entrance to Imara Daima estate (see Fig. 4.18 and Fig.4.19), is another primary informality worth examining. Nyange, the main mechanic at the garage, trained at the National Youth Service (NYS). On qualifying from NYS, he was unable to join the formal labour market, and therefore decided to venture into the informal (jua kali) sector. Nyange and colleagues originally started operating inside the Imara Daima estate in 1996, but were moved to the external entrance area in 1998, when the estates’ residents insisted that they did not want informal activities within the estate boundaries. Although these informalities offer a source of livelihood to the not-so-poor urban residents, middle income residents may not sanction their operations in their midst. This productive informal sub-sector, often known as Jua Kali (hot sun), literally meaning working under the sun, plays a significant role in the economy of Nairobi. It encompasses manufacturing, repair and provision of services (Syagga, 2002:41), with this garage offering motor vehicle repair services. Fig.4.18 Garage shed Fig.4.19 Clients’ Vehicles The ¼ acre (0.1 Ha) land on which “Hollywood Garage” operates, was allocated by the authority of the then 1998 Nairobi Provincial Commissioner, for the sum of Kshs. 10,000 ($ 125), this money was paid to the area chief in consideration for the allocation. Here again as Syagga posits; 126 the informal system of land and housing supply should be seen as a function of political intermediation of varied but mutually reinforcing interests in urban land and housing (Syagga, 2002b:18). On top of the allocation fee, the garage pays the city council a Temporary Occupation License (TOL) fee of Kshs. 7,200 ($ 90) per year plus a Trade License fee of Kshs. 5,200 ($ 65) annually. In terms of employment opportunities, the garage generates employment for 10 mechanics on a full time basis and 5 trainees on a part time basis. Every one of the ten mechanics attends to their own clients, with the various trades of panel beating and spray painting, mechanical and electrical repairs being dealt with separately. The garage opens from 6.30hours to 18.30 hours (Monday to Saturday) and 6.30 hours to 13.00 hours on Sundays. This shows that people in this sector of the economy must put in long working hours in attempting to meet their financial obligations. On average, “Hollywood garage” repairs about 3 cars per day during week days, with the number increasing to about 10 cars over the weekends. Charges for the repairs are negotiated on a case by case basis. In an effort to increase the income from the plot, one corner of the plot has been sub-let to a food kiosk which pays Kshs. 3,000 ($ 37.5) monthly rent. The owner of the kiosk who is a resident in the adjacent middle income Villa Franca estate has made an illegal power connection from his house to the kiosk. This shows how informalities straddle across the socio-economic classes in Nairobi. There are no infrastructural services provided on the site, making it necessary for the garage staff and clients to use the sanitation facilities of “Home Pub” which is some 200m away. They however use one corner of the plot as a urinal. Water is sourced at the nearby water vendor’s tap at Kshs. 3 ($ 0.0375) for a 20 litre jerrican Fig.4.20. The garage currently does not have power connection, but it can be officially connected by the Kenya Power and Lighting Company, if a connection fee of Kshs. 30,000 ($375) is paid. All the costs involved in these informalities, show that it is not free to operate in the informal as commonly perceived (De Soto, 2001). Although Hollywood garage operates on a road reserve, and strictly speaking can be classed as illegal, Nyange and his group do not perceive this business as illegal. In their eyes the business is legitimate since it was sanctioned by the provincial administration, 127 and all the necessary trading licenses have been paid for. It is clear from this state of affairs that the City Council is unable to manage the urban process, as the dual colonial provincial/municipal control of urban resources has yet to be resolved.60 Fig.4.20, Informal water point Mukuru Kwa Njenga Informal Settlement It was mentioned earlier that the largest primary informality is manifested physically by the dwelling units of informal settlements.61 One such settlement is Mukuru Kwa Njenga. It is situated off Mombasa Road in the south east of Nairobi. Fig 4.21 shows an aerial view of this settlement and its environs. Njenga was the first person to settle in this area in the late 1970s, when he built a bar to cater for the needs of many low income workers, particularly those who were engaged in quarrying activities at the nearby quarries. Before this time, the area was hardly inhabited and had only become part of the city area after 60 61 See for example; Thornton White, et al. 1948; Burton, 2002. See Table 3. 128 the 1963 extension of the city boundaries.62 Fig. 4.22 shows how this area has undergone transformations from the 1970s to now. Fig.4.21, Mukuru Kwa Njenga Settlement (Imara Daima at lower left of image) 62 See chapter3 – Post-colonial Nairobi 129 Mukuru Kwa Njenga 1978 Mukuru Kwa Njenga 1998 Mukuru Kwa Njenga 2003 Fig.4.22, Evolution of Mukuru Kwa Njenga (1978-2003) In Mukuru Kwa Njenga settlement, named after Mr. Njenga the first settler in the area, the dominant tenure system is the non-formal de facto tenure. This is a tenure system which is insufficient to offer proper land ownership (Syagga, 2002:72). Typically the dwelling units are primarily single rooms of approximately 12ft x 12 ft, a size similar to 130 rooms in other informal settlements (Hirst, 1994; Syagga, 2002). In this regards, Mwangi, posits that; 90% of households in the informal settlements of Nairobi occupy single rooms of between 9 and 14 square meters. The occupancy is 3-5 persons per room (Mwangi, 1997). Accommodation provided in informal settlements is mainly in single rooms measuring approximately 10m² (12ft x 12ft). The differences however occur according to the dwelling type and the types of construction materials used and the level of infrastructure services available (NISCC, 1997; Syagga, 2002b). This particular model/module of dwelling generation can be traced to the colonial bed-space concept that resulted in the 1921 bachelor quarters at Kariokor (Thornton White et al, 1948; Hirst, 1994)63 The occupancy of 3-5 people per room is tantamount to overcrowding, which in effect gives a false impression of affordability and the high rents per room (Syagga, 2002b). Players in the informal sector have such low incomes that they can not exercise choice but take what is available. They thus have no freedom of entry or exit from the available accommodation (Mugo, 2000 in Syagga, 2002b: 6). Andimi exemplifies a typical tenant in Mukuru Kwa Njenga. When he first came to Nairobi, he lived in the adjacent Quarry area between 1985 and 1989. He then moved to Mukuru Kwa Njenga in 1990, and currently is living in his fourth rental room (house). The changes in tenancies over the last 15 years are due to various reasons, ranging from non-compliance with rent payment schedules to forced evictions. At the time of the study, Andimi, occupied a 10ft x12ft room for which he paid a rent of Kshs.400 ($ 5) per month, and bought water at the rate of Kshs.3 per 20 litre jerrican, a price which rose to Kshs. 5 when there was scarcity. He used kerosene for cooking and lighting was by way of a tin lamp (kuroboi). Fig 4.23 shows the plan and sections of this particular dwelling unit on plot No. 646, while Fig. 4.24, 4.25 and 4.26 show some images of the same unit and the surroundings. Andimi informed me that his landlord/structure owner has no official ownership document, except that the landlord’s name is in a register kept at the chief’s office, and also in another register kept at the village chairman’s house. In order to be allocated a plot to build on, the structure owner 63 See chapter 3 – Consolidation period. 131 paid Kshs 5,000 ($ 62.5) to the area chief and the village chairman for each room built, in this case a total of Kshs 20,000 ($ 250) for the four rooms. I was also made to understand that, in order to allocate the land, the two officials got authority from the area Member of Parliament (MP). 10' - 0" c.g.i. roof ing on timber frame 8' - 6" A RM. 1 SECTION A - A PLAN RM. 3 7' - 0" c.g.i. roof ing on timber frame RM. 1 cement screed on thin slab 50mm thick. SECTION B - B 10'-0" RM. 1 3'-6" 10'-0" B RM. 3 12'-0" 24'-0" 12'-0" B cement screed on thin slab 50mm thick. 8' - 6" A 7' - 0" 12' - 0" c.g.i. walling and roof ing on timber frame RM. 2 RM. 4 SCALE. 0 3'-4" 6'-8" 13'-4" 20'-0" PLAN - ROOM CLUSTER Fig 4.23, Typical Dwellings - Mukuru Kwa Njenga. 132 From a design point of view, there is little privacy in this settlement. Andimi enters directly from the outside, into the communal corridor, which serves all the four tenants/rooms. Each room/house serves as a multi-purpose space, akin to the 18th Century European worker’s dwelling unit.64 There are no sanitary facilities on plot 646, residents in this plot use the group toilets (pit latrines) located on an adjacent plot (Fig. 4.27). These latrines are operated privately and commercially, where the residents pay Kshs.2 per visit. There are no bathing/shower facilities, therefore most residents bathe inside their dwellings. In some informal settlements, research has shown that up to 50 people use one pit latrine, while health regulations require that one latrine and one bath/shower for each family or a group not exceeding 6 persons (NACHU, 1990 in Syagga, 2002:52). Fig.4.24 Entry Area, Andimi’s “House” 64 Fig.4.25 Interior, Andimi’s “House” See Samuels, I. et al. 2004; Engels, F. 1993 (McLellan, D. ed). 133 Fig.4.26 Dwellings under Power Lines (Andimi’s House is in one of these). There is also no regular collection of garbage in these settlements, resulting in huge heaps of uncollected garbage, as the case of Mukuru Kwa Njenga Fig.4.28. In Nairobi, the collection and disposal of refuse has been falling from 89.9% in 1978 to only 35% in 1988. By 1987, a few private firms were providing refuse removal services in affluent areas of the city at a fee. The number of private providers increased during the 1990s and by 1997, there were 60 small firms registered under the Companies Act collecting garbage within the city (Syagga, 2002:53). Fig.4.27 Commercial Pit Latrines Fig.4.28 Garbage Heap 134 The water supply within the city is no better; only 11.7% of households have water connections, in addition more than 55% of Nairobi’s population live in informal settlements, where there are hardly any connections. Apart from limited access to water sources, residents of informal settlements also experience water shortages including dry taps. Most of the households therefore rely on community water points operated by private entrepreneurs (Syagga, 2002:50). Infrastructural facilities are also minimal, for example all the access roads/footpaths in the settlement were formed by continuous pedestrian movement, which wore out the grass cover and formed earthen thoroughfares as can be seen in Fig. 4.29. Moreover an inventory of Nairobi’s informal settlements shows that; Urban services in informal settlements are non existent or minimal. Roads, pathways and drainage channels are made of earth and flooding is common (Matrix Development Consultants, 1993 in Syagga, 2002:53). Informal settlement areas do not have city or government health facilities. NGOs and private individuals are the only health care agencies providing free and/or subsidised services. Fig 4.30 shows a privately run health facility in Mukuru Kwa Njenga. This conditions informal settlement dwellers to go to neighbouring higher income settlements if they have to use government and city facilities (Syagga, 2002:54). The situation is no different with regard to schools, there are no schools in Mukuru Kwa Njenga except one run by the catholic mission and a private one recently opened in the newer part of the settlement (Fig. 4.31). The nearby Embakasi Girls Secondary School was not meant to serve this settlement, but the larger Embakasi area. In fact it is only in the last five years that the settlement has engulfed this school. 135 Fig. 4.29, Unpaved Roads/Footpaths – Doubling as drainage Channels Fig.4.30, Private Health Clinic. Fig.4.31 Private School (So-called Academy) 136 Informal Settlements in General Informal settlements accommodate 60% of the population in Nairobi on some 5% of the residential land, as shown in Fig.4.32. Accordingly, it is not just that the settlements have no infrastructural facilities, but that they are seriously overcrowded (Syagga, 2002b:28). Informal housing based on the profit motive as a solution for shelter, is increasing in all informal settlements in Nairobi. Informal rental housing is large scale in Kenya, unlike the common view that it is the owner occupation which is dominant, the majority of slum dwellers are tenants as exemplified by studies of Mathare, Korogocho, Kibera and other settlements (Amis, 1984; Lee Smith, 1990; Gitau, 1999). For example, Lee Smith’s 1990 study, found that 87% of inhabitants in Korogocho were tenants (Syagga, 2002:92) The haphazard nature of informal urbanisation eventually creates a haphazard urban fabric. According to Syagga, 2002b any attempt to upgrade slums, must be based on consensus among structure owners (absentee and resident) and tenants. The consensus building must balance the incentives and investment potential of structure owners and the basic needs and human rights of the very poor. Where as I agree with this position, I need to reiterate the role the individual dwelling unit plays in the creation of an urban environment. The design of the dwelling unit is normally ignored on the pretext that infrastructural services i.e. roads, sewage, water and power supply are more important by virtue of their superior investments. This leads to the propagation of the barrack type of housing, similar to the 1920s colonial typology, which results in monotonous neighbourhoods, such as Mathare 4A, Fig.4.33. It is important that the spatial configuration and the dwelling unit design be given high priority, because the entire neighbourhood to the walking man is characterised by the streets and footpaths which are determined by the urban edge. This edge is defined by the built forms, which must be designed accordingly in order to create the desired neighbourhood urbanscape/morphology. Infrastructural services although important, have very little impact on the urban morphology, and should therefore not be the sole determinant in settlement upgrading. 137 Fig. 4.32, Location of Informal settlements. source: Matrix Dev. Consultants 1993 Fig.4.33, Mathare 4A Dwellings - Barrack Type 138 The costs of well designed dwelling typologies, whether privately or publicly sourced will have little impact on the overall cost of the dwelling. The cost of each room as at 2000, was Kshs. 20,000 ($ 250) (Syagga, 2002b), this changes marginally as a result of good design. Moreover, if the upgrading is done on a large scale, the costs of good design will be absorbed by the large numbers due to economies of scale. There is also an added disadvantage of horizontal upgrading, in that it increases urban sprawl, which further stretches the limited infrastructural services. This can be reduced if vertical (multilayered) upgrading approaches are engaged.65 There are other players in primary informalities such as the roadside steel/timber fabricators, who dot the Nairobi landscape; Fig. 4.34 shows a good example. The matatu mode of transport can also be seen as being part of primary informalities. The lack of planning for public transport in Nairobi resulted in the birth of Matatus, which was a default solution for the transport system. Matatus operated without a legal framework until the Traffic Amendment Act of 1984, which provided Matatus with a special form of legislation (Syagga, 2002:54).66 Over the years, Matatus have operated in an ad hoc manner, and even today they do not have proper termini, they park and continue to operate in an ad hoc manner on the Nairobi Streets. However they are the most important mode of transport for the majority of Nairobians, and for many Kenyans Fig. 4.35. Fig.4.34, Roadside Furniture Vending Fig.4.35, Matatu Transport 65 The three dimensional approach has been tried by Pamoja Trust in their Huruma Upgrading Project. See chapter 3 – Planning, Regularisation and Upgrading. 66 See chapter 3 – Post-colonial Nairobi. 139 Intermediate Informalities Intermediate informalities are activities/processes which are settlement based and involve mostly the construction of residences with a few commercial outlets; in general they have secure land tenure, normally on leasehold for 99 years.67 The main players/actors in these informalities are the middle income group although a few people from the high income group also participate as absentee players. The main activity in this category being building construction, has led to two scenarios; where the developments can either be settlement formation or settlement modification. Quite often in settlement formation, the proprietors have to build their own infrastructural facilities in addition to building the houses; this is because the provision of most urban services may be minimal or non existent. While in settlement modifications, the proprietors transform the existing spatial configurations by way of alterations and extensions (transformations), thereby putting additional pressure on the existing services. This later phenomenon is basically the infiltration of the informal into the formal, creating a hybrid urban fabric or what Soliman, 2002 referred to as ex-formal. This phenomenon where the informal infiltrates the formal is discussed in detail in chapter five. Many fundis get employment in this category of informalities, including unskilled persons, as nearly all the buildings/services are built on labour contract basis. These activities have a multiplier effect as the survivalist food vendors are drawn in to supply food to the construction workers. The practice/urban process of settlement formation and transformation, takes advantage of existing formal infrastructural services, similar to what primary informalities do. However, intermediate informalities have a major impact on the urban built fabric, as it generates a large variety of building types through the assertion of individuality in an effort to create identity. The constructions quite often use approved standard building materials like stone, concrete blocks, concrete tiles etc. In the process they create a scenario which is not normally possible in a centralised settlement delivery process.68 Many constructions however, rarely have official council approval, and are therefore statutorily illegal. In addition, the infrastructural services built on a self-help basis may or may not be officially approved, although they can later on be taken over by the 67 68 See Table 3. See the discussion on the issue of autonomy and heteronomy by Turner, 1976. 140 council. Such services will continue to raise doubt with regard to standards in terms of design and construction. Many proprietors in this category are moneyed, as they spend hundreds of thousands to millions of Kenya shillings in carrying out their operations. They also pay statutory payments including, land rates and rents, however the sums involved are quite low, as the figures were probably set more than 30 years ago and have never been revised. On this score, if the council were to charge appropriate land rents/rates, it could possibly raise enough capital to fix the infrastructural services in the city. In cases where developers create new settlements, they are unable to build paved roads, and therefore suffer the consequences of inclement weather. They may also be cut off from their residences, if the council were to change the road network, since officially their roads do not exist.69 From an economic perspective, operators in intermediate informalities, command some respect in financial institutions, and can access formal funds using their title deeds as collateral. In addition to this financial capability, they are able to have political freedom as they can avoid the patronage syndrome that afflicts most urban poor. However their numbers are not many enough to form a critical mass for the advancement of their political agenda, and therefore remain on the political fringes, unless of course they, at individual level, they are incorporated/join the circles of the political elite. Intermediate informalities occur primarily due to the lack of affordable serviced land for middle income residents of Nairobi. Developers in this category, generally acquire unserviced land which they subdivide and build the infrastructural services on a self-help basis. This category of informalities also includes formally planned middle income residential areas which undergo transformations and eventually become informalised. Over the years many middle income formally designed estates have become ex-formal, due to this process, one of these ex-formal estates is discussed in detail in the next chapter. A recent intermediate informality which presents an interesting case of place making (settlement formation) is Jamhuri II estate. This estate is situated approximately 5km from the city centre in the western part of Nairobi just off Ngong Road. 69 See chapter 2 – Other debates on Informality. 141 Before discussing the transformations taking place in Jamhuri II, I briefly explain how one gets to this estate from the CBD. From the CBD, you drive west along Haile Selassie Avenue, which joins Ngong Road at the Nairobi Club. Driving along Ngong road you pass Kenyatta National Hospital to the left then come to the City Mortuary roundabout. You proceed straight on passed the Adams Arcade shopping centre and onto the roundabout at the intersection of Elgeyo Marakwet and Suna roads. After negotiating the roundabout approximately 300metres further on along Ngong Road, the Harlequins Rugby Football Union plus Impala Club will be to your left. At this point and just before the new Nakumatt Hyper Market to the right, and the Kenya Science Teacher’s College to the left, you turn left into Kibera Station Road. As you drive on, you pass the roadside tree nursery earlier discussed70 to the left, then the road turns left as you enter Jamhuri I estate. But as you turn into Jamhuri I, you leave the road leading straight to the Kibera railway station, with Jamhuri Park in the distance to the right and beyond the railway line. You are now driving in a boulevard of mature benjamina trees at the edge of Jamhuri I estate Fig.4.36, then suddenly, straight ahead of you are several high rise blocks Fig.4.37. These are the commercial cum residential developments at one edge of Jamhuri II estate, which have some shopping outlets. You will in the meanwhile be seeing a fruit vendor to your right Fig.4.38, as you enter Jamhuri II. You are now in the estate and noticing a transformed environment, particularly if you used to visit Kariuki’s off licence pub (masandukuni) that operated in the 1970s at the Kibera station. At that time this area was just bush land with outcrops of some trees, while the planting in Jamhuri II was hardly noticeable. I will now discuss how this estate has come to be and the efforts individual residents are making in creating this new reality. 70 See Fig.4.3. 142 Fig.4.36 Boulevard - Jamhuri I Fig.4.37 High-rise Blocks Jamhuri II Fig.3.38 Fruit Vendor – Entrance to Jamhuri II Jamhuri II was conceived as an extension to Jamhuri I estate, a tenant-purchase middle income residential area built in the late 1960s. This idea of extending the Jamhuri development was conceived by the Nairobi City Council in the early 1990s. The layout and plot subdivision for Jamhuri II was done in house by the city council’s planning and architecture department in 1992 as can be seen in Fig. 4.39. In this layout, apart from the provision of some open spaces and a site for a nursery school, there is no provision for any other social amenities. All the other land is divided into individual residential plots; in fact the awkward configuration of the layout shows that there must have been many interested parties in this land, with the resultant layout being a compromise solution. After the subdivision had been approved, ideally the plots should have been advertised in accordance to the Lands Act Cap280. This was never done, as the plots were internally 143 allotted to senior council officers and their cronies from both the public and private sectors. Fig.4.39 Jamhuri II – Plot Subdivision Layout The Lands Act specifically provides that before public land is allocated, the Commissioner of Lands should advertise that land and sell it at a public auction to the highest bidder.71 This is not normally the case as Syagga, 2002 observed that; Tragically, the very people charged with the duty of protecting public land are the ones plundering Kenya’s heritage and resources (Syagga, 2002:66). There is evidence to show that although many allottees from outside the council went ahead and paid the necessary government levies in pursuit of title deeds, most council allottees immediately sold their plots to third parties without incurring any costs, in other words, they made free money. At that time (1993), the going price for the plots which measure approximately 8m x 25m was about Kshs. 300,000 ($ 3,750). 71 The discussion on the procedure for the allocation of public land is articulated by Syagga, 2002. 144 The initial idea of developing Jamhuri II was to develop a middle income site-and-service scheme, where the allottees would get serviced plots at a stipulated fee, then build their houses individually. This never happened, and all the council did was to place the subdivision beacons, leaving the plot owners with no option but to source the infrastructural services on their own. Fig. 4.40 shows the time series images of Jamhuri II, showing the morphological transformation of the settlement over time from an open ground with some shrubs in 1970, to a dense urban development with unpaved roads similar to those found in informal settlements. Jamhuri II 1970 Jamhuri II 1978 Jamhuri II 1998 Jamhuri II 2003 Fig.4.40 Time Series Images – Jamhuri II With regard to roads/footpaths, no communal efforts have been made for paving, and they remain earthen. There is also no street lighting, but many people have lights on their gates with additional security lighting on the buildings. Security in the estate is basically ad-hoc, although a few courts have organised themselves and have built gates to their cluster of houses. My key informant Mr. Kinuthia confirmed that in general the estate is fairly safe, to the extent that some houses have no security at all. This is a typical case where collective consumption goods can not be built on a self-help basis due the 145 individualism of plot owners, and the lack of a framework to articulate the collective good.72 I now turn to the discussion on what efforts individuals are making in creating this new reality in Jamhuri II. The development by Kinuthia on plot No. 69 will be used to demonstrate how, many plot owners have gone about procuring their houses. Kinuthia bought this plot in 1997, becoming the second owner from the initial allottee of 1993. The initial allottee had made no improvements over the four year period, and had basically held the land for speculation purposes. The plot which measures 8m x 22.5m (0.018ha) was bought for Kshs. 750,000 ($ 9,375). Since there were no services on site apart from the corner beacons, some basic services had to be installed before house construction could begin. In order of priority water had to be connected to the site first, this was done by paying the city council water department a sum of Kshs.15, 000 ($187.5), in addition to the pipes for connection, which were bought by each individual developer. For this particular case, the nearest water connection point was 15m away; therefore the pipes didn’t cost much, since the length involved was small. The next task was to connect electricity to the site; this was done by joining forces with other three nearby plot owners, which helped reduce the overall costs. The nearest point of tapping power was 30m away, which required two new poles to be erected to support the supply cable. This exercise cost Kshs.25, 000 ($ 312.5) for each of the four plots. Finally the sewer had to be connected to the plot; again 8 plot owners combined resources to connect the sewer to the nearest point of connection which was about 30m away. This cost each plot owner Kshs.30, 000 ($ 375). These costs are fairly reasonable since the service distances involved are not too long. The pioneer plot owners to start building however, paid much more as the service distances were much longer. Here again a design and supervision fee was paid for the sewer connection. Kinuthia who graduated from the University of Nairobi in the early 1990s, is one of the many middle income Nairobians, who are unable to access formal housing. Although he is willing and able to afford good quality housing, the market is not able to provide this type of housing. These circumstances therefore force many middle income people to resort to self-help based housing procurement methods. 72 In chapter 2, I discuss Castells concept of collective consumption goods, Susser, 2002. 146 This self-help approach to the procurement of housing and infrastructure services is a reality most Nairobi middle income residents have to contend with on a daily basis. They can however consider themselves better off; at least they are able to meet the costs of these services. The poor who can’t pay for these services have no possibility of accessing them. With regard to formalising the property, the plans for Kinuthia’s development on plot No.69 were submitted to the council in the year 2000; to date they have never been approved, meaning that for all practical purposes, Kinuthia’s property is illegal. Although the extension of the sewer to every plot was the council’s pre-condition before approving plans to any development in Jamhuri II, even after meeting this condition, no plans had been approved for any of the developments taking place in this estate, as at April 2005. The council has chosen to turn a blind eye to the goings on assuming that these are illegal developments, yet on the one hand they are using officially sanctioned infrastructure services.73 There are several legal requirements for development in this area, these include; a 6m building set back from the road reserve, a 50% plot coverage and a 75% plot ratio. Kinuthia’s development on plot No.69, has generally met these requirements, although both coverage and plot ratio have been exceeded slightly. Figs. 4.41 - 4.43, show the section and plans of this development. The construction of this house started in August 2000 on a labour contract basis, and by December 2003 the skeleton (shell) was complete. This is the time Kinuthia and family moved in, and has since been working on the finishes, so far the construction had cost in excess of Kshs 3,000,000 ($ 37,500) as at April 2005. These costs are not low by Kenyan standards, making it clear that the residents in this estate can afford to pay for serviced land. However due to the inability of the city council to deliver serviced land; they are forced to use informal procurement methods. Once again, like primary informalities, urbanisation occurring by default. Fig. 4.43 and 4.44 show some views of the Kinuthia house. 73 This situation can be attributed to the ambivalence displayed by bureaucrats towards the phenomenon of informality as discussed in chapter 2. 147 Fig. 4.41, Typical Section – Kinuthia House Fig.4.42, Ground Floor Plan The urban fabric generated by Jamhuri II is quite problematic. First of all it is common knowledge that the current mayor of Nairobi and many senior council officers own plots in this estate. Some of them have built flats in contravention of their own by-laws, which 148 require that each plot should be developed with one residential unit on not more than two floors. This scenario, where basic rules are contravened by council officials, makes it difficult if not impossible for other plot owners to follow the rules. Many plot owners have therefore built flats on their plots, a condition which will definitely put more pressure on the self-help infrastructural services, whose quality cannot be ascertained. Fig.4.43, First Floor Plan Fig.4.44 Entrance View Fig.4.45, Stair Detail – Lit by skylight. Fig. 4.46 and 4.47 show examples of some flats in Jamhuri II, with some rising to six levels. Another by-law that has been grossly abused is the 6m building set back along the 149 access roads. Many plot owners have built up to the plot boundary, creating in some cases coverage of up to 80%. From a design point of view, it is unlikely that the interior spaces resulting from this kind of coverage will be adequately lit naturally, in addition to restricting air movement particularly when the buildings have more than two floors. Fig. 4.48 illustrates how building to the plot boundary without a set back impacts on the street sight lines. It is particularly dangerous for car drivers at junctions when set backs are ignored.74 Fig.4.46, 3 Storey Flats Fig.4.47, 6 Storey Developments Fig.4.48, Urban Edge Definition – Lack of Building set-back 74 For the discussion of the facade as a place of conflict between the house and the city, see Samuels, I. et al. 2004:56. 150 In terms of overall image of the estate, most people are struggling to generate individuality visually as can be seen in Figs. 4.49 and 4.50.75 Where as this may be a welcome endeavour, it tends to be overdone and ideally requires some control. This control can only come from the city council, yet the same council is the culprit, making it even more precarious. The mode of development in Jamhuri II is not sustainable, as it does not take advantage of the economies of scale. It has buildings at various stages of completion, from empty plots to fully built houses. Some empty plot owners practise urban agriculture before commencing building construction Fig. 4.51, while others are at the walling stage as others are at the roofing stage. What is clear is that all these plot owners can afford high standard of housing, but end up getting sub-standard housing, due to the ad hoc nature of construction. This can be avoided if the city council could streamline its housing delivery procedures, if at all there are any. For example, people are not willing to invest in the paving of the roads as these do not affect them directly as they fall outside their plot boundaries. If the council were to however, co-ordinate road construction and street lighting in the estate, many plot owners may be willing to contribute financially. Fig. 4.52 shows the condition of one of the access roads within the estate. Fig. 4.49, Struggle for Identity Fig.4.50, Visual Articulation The key players in the realisation of Jamhuri II are the individual plot owners, the local artisans (fundis), and the material suppliers. Nearly all the buildings are built on a labour contract where the owner buys materials and the fundi builds and gets paid for his/her labour. Generally all the other workers who assist the fundi are paid directly by the plot 75 See Turner, 1976 for the discussion on variety and subsidiarity. 151 owner on a daily or weekly basis. Where as this procurement process creates jobs for many, it is not that efficient. The plot owner spends time purchasing materials when she/he could be gainfully engaged elsewhere by letting more competent people deal with construction. Many a times, plot owners have lost money through petty suppliers and other intermediaries. Fig.4.51, Urban Agriculture Fig.4.52, Main Access Road Like in primary informalities, female plot owners tend to loose more to these intermediaries than their male counterparts. This basically is a result of lay plot owners trying to tread on new territory of building construction. Observation in Nairobi, shows that, in comparison to male structure owners, women tend to spend more in developing there structures than male structure owners. This is largely due to the trust they put on the males who assist them during structure development. Once they have a rapport with such individuals they do not scrutinise the cost of building materials, and what they are told the provincial administration and/or KANU youth requires (by way of protection money). This seems to be more serious for women who do not stay within informal settlements and have to rely on provincial administration officers, especially the chief and KANU youth wings (Syagga, 2002b:23). As discussed in primary informalities, the urban edge definition is crucial in city making. Here again, the urban edge will play a role in the definition the overall urban fabric. The fact that many people are disregarding the 6m building set back generates a new urban edge which poses new design/planning questions. May be the planners should in the first place allow for no building set back, but make the road widths generous to be able to take 152 the carriageway and the services that go with it. Making sure that proper sight lines can be achieved at T junctions without the set backs. Evidence in Nairobi shows that people are always tempted to create additional indoor space on any open ground, either for family use or for subletting purposes. These are the realities on the ground and must be addressed squarely. Affluent Informalities Affluent informalities are activities/processes that are settlement based with a focus on residential development, and do not engage in commercial/business activities at all. They have secure land tenure, either absolute or on leasehold for 99 years. These tenure conditions oblige them to pay the relevant land rents and rates, which as discussed earlier are rather low and need revising upwards. This category of informalities is dominated by the high income group and is the least informal (most formal), and takes advantage of the availability of well serviced land. Basically, these informalities are based in areas zoned for low density, and therefore their impact on the built fabric and infrastructural services is minimal. The construction of additional space/residences will impact marginally on water and electricity supply, but will have no impact on the sewage system. This is because most residences rely on localised sewage treatment by way of septic tanks, located within each residential plot. To operate in this category, one requires millions of Kenya shillings, as most proprietors engage in conspicuous consumption, to the extent of even importing building materials.76 Like their intermediate counterparts, they also create jobs for local fundis and labourers, and also generate a multiplier effect extending to the food vendors in the survivalist category. In terms of built form, they evolve an eclectic architectural typology, as each developer uses his/her own style, in an effort of stamping physically their individual identities. Like the developments in intermediate informalities, the plans for residences/transformations in this category may or may not have official council approval. Therefore, if they have not been approved, it means they are illegal developments. 76 See Table 3. 153 Unlike many low and middle income areas, the zones of affluent informalities are not served with social amenities. One of the reasons for this situation could be that; the council did not enforce their own laws, which require 20% of the land to be reserved for social amenities. The developers therefore took advantage of this loophole and subdivided all the land into residential plots. The result is that; the residents are thus forced to travel long distances in order to access schools, shopping, recreation etc. Luckily, these residents can afford these kinds of expenses, however on a city or national level, it is an unnecessary drain on resources that could have otherwise been saved and utilised for other pressing needs. Politically, this group plays a major role in the governance of the city and country. This group ideally replaced the colonial ruling class and as discussed earlier, enjoys an unfair privileged position relative to other citizens. They are able to push their political agenda with ease, and many people in this category enjoy political appointments to parastatals and other national institutions.77 One of the residential areas experiencing this type of informality is Runda, situated approximately 10km to the north of Nairobi CBD. Runda was originally a coffee farm, and was part of the White Highlands at the turn of the last century. Most of these farms were established as part of the process of transforming Africans to wage labourers which began in 1902 (Emig and Ismail, 1980). Over the years, Runda has been transformed from a coffee farm, to become one of the most affluent suburbs of Nairobi. Fig.4.53 shows aerial images of how this morphological transformation has taken place over the last 30 years or so. 77 See chapter 3 – Post-colonial Nairobi. 154 Runda 1970- A Coffee Farm Runda 2003 – High Income Suburb Fig.4.53, Morphological Transformations of Runda Due to the proximity of Runda to Nairobi, and the continued increase in urban population, it was inevitable that nearby farmlands had eventually to be converted to residential areas. This is what happened at Runda when the coffee owners, subdivided the estate and sold the sub-divided parcels of land to interested companies for residential development. The developers were either to fully built residences on individual plots or to subdivide the parcels into serviced plots for sale on the open market, such that individuals could build their own houses. According to planning requirements, the subdivisions had to allow 20% of the land to be set aside for community and social amenities. This was not observed, as most developers divided all their parcels into residential plots. The Nairobi city council which was supposed to ensure that land is set aside for social amenities did not take that responsibility. In this regard Syagga, 2002 notes that; The councils have also neglected their role of guiding private developers, resulting in these developers, developing housing without leaving land for infrastructure and services (Syagga, 2002:60). Fig 4.54 shows an example of one such subdivision, this particular parcel was bought by National Housing Corporation and subdivided into ½ acre plots without setting aside any land for infrastructure and other social amenities. 155 Fig.4.54, Typical Plot Subdivision – Runda (No provision for social amenities) The development of Runda has basically been confined to residential development only, without the requisite social amenities like; schools, shopping centres and open spaces that make housing areas sustainable. Old Runda built in 1978 followed this pattern of development, where complete built units were sold on the open market Fig. 4.55. The result of this mode of development is that the residents crisscross the city on a daily basis; taking children to and from school, going shopping or going for recreation. 156 Fig.4.55, Layout - Old Runda – (Aerial View 2003) The building of the “Village Market” Fig. 4.56, in the 1990s in close proximity to Runda has to some degree, shortened the distance covered for shopping and recreation. The results of this is that “Village Market” gets quite congested with people from Runda and other neighbourhoods like Wispers, Gigiri and Roselyn in addition to people from other parts of the city. Figs 4.57, 58, 59 and 4.60 show images of “Village Market” which has been dubbed as one of the leading global shopping centres.78 Apart from the informal land use pattern in Runda, many house owners have made alterations and extensions (transformations) to their houses without seeking the council’s approval, there by stretching the carrying capacity of infrastructural services. One such example is the development on plot No.97 in old Runda. The extensions and alterations made on this property almost double the size of the original development. Figs. 4.61-4.64 show the site plan, plans, sections and elevations of the transformed house. This development contravenes the allowable plot ratio and coverage in this area and in the process increases the residential density, and the accompanying loss of open space. With regard to construction, the local fundi, like we saw earlier is a major player, as the construction of these extensions and alterations were executed through a labour contract. 78 Village Market is basically a shopping centre for Nairobi’s affluent. 157 Fig.4.56, Village Market – Aerial View and Entrance Drive Fig.4.57, Food Court Fig.4.58, Water Fountain Affluent informalities have little impact on the visual urban fabric, as the buildings affected are set in large compounds, and can only be read at close proximity. One peculiar observation is that affluent developers indulge in conspicuous consumption by way of using very expensive building materials, often imported from abroad, particularly Italy. This makes properties in Runda quite expensive, averaging Kshs 15,000,000 to 20,000,000 ($ 187,500-250,000). Currently ½ acre (0.2ha) of land in Runda costs between Kshs 2,500,000 to 3,000,000 ($ 31,250-37,500). 158 Fig.4.59, Shopping Arcade Fig.4.60, Main Entrance Here again fundamental questions are raised; may be the densities set by the council are too low for urban development in this area. Secondly, much as there is freedom of choice, what impact does the importation of building materials have on the national economy? These are important issues to be addressed, because local materials, sensitively used can provide similar quality construction if not better. In addition, by increasing the densities, areas like Runda can accommodate more people and therefore helping reduce urban sprawl. Fig.4.61, Aerial View Site Plan - Plot 97 159 Fig.4.62, Ground Floor Plan – Plot 97 Fig.4.63, First Floor Plan – Plot 97 160 Fig.4.64, Sections and Elevations – Plot 97 161 5. INFORMALISING THE FORMAL Introduction In this chapter, lets’ turn to what I have called intermediate informalities in more detail, with the main focus being on morphological transformations taking place in Buru Buru, a settlement which was originally formal, but is gradually becoming informal or what Soliman(2002) would call ex-formal. I will use the Mumias South Road Corridor, which forms the central circulation spine in Buru Buru housing estate, to illustrate this process of informalising the formal. The major transformations in Buru Buru, take place along the circulation corridors, this therefore justifies the choice of the Mumias South Corridor. The first development of phase one and two of Buru Buru was designed without a building setback and buildings were built up to the plot boundary Figs.5.1 and 5.2. Over the years, this interface between the public and the private domains has undergone major morphological transformations. Fig. 5.1, No setback - Phase 1 Fig.5.2, No setback - Phase 2 Unlike phase one and two, phase four and five had a 9m building setback/line within the Mumias South Road corridor. It is within this setback/interface zone that major transformations have taken place creating a completely new built fabric (Fig.5.3 and 5.4). 162 How these transformations occur and who are the actors in this urban process is what I discuss in the rest of this chapter. Fig.5.3, 9m Set-back Phase 4 Fig.5.4 Transformed 9m Set-back Phase 5 Evolution of Buru Buru Buru Buru’s development can be traced back to the 1962 Regional Boundaries Commission, which emphasised the inclusion, within the boundary of the city, adequate land for future residential and commercial development (Hirst, 1994; Nevanlinna, 1996:204).79 In this regard the city boundary was extended to include a large extent of farmland to the east previously known as Donholm Farm. Over the years the farmland has been transformed into a vibrant residential area with more than 50,000 inhabitants (Fig.5.5). In addition to the above early provisions, the 1973 Metropolitan Growth Strategy (MGS) further articulated the expansion of the city towards the east by proposing the development of high density housing for the low and middle income groups in this area (Emig and Ismail, 1980). During this period, the dominant global development paradigms were the growth and redistribution theory and the basic needs theory.80 Based on these theories, the developed world poured a lot of resources in the developing world, which were aimed at improving productive and welfare conditions of the poor. Urban development was geared towards facilitation and was project based (Syagga, 2002:1). It is within the above context that Buru Buru was conceived and executed. 79 80 See the 1973 MGS. Syagga, 2002. 163 One major reason for Buru Buru’s development was to increase the housing stock in the city, in order to meet the ever increasing housing demand, in this case for middle income residents. According to Syagga, 2002 by early 1970s the National Housing Corporation was building an average of 2000 housing units per year, most of them in Nairobi, and basically tenant purchase and rental houses. This policy of building rental and tenant purchase schemes proved to be unsustainable, as the production process hardly catered for more than 10% of the required housing for Nairobi.81 This experience gained from the tenant purchase/rental housing led to the policy of mortgage housing, which became the underpinning policy in the development of Buru Buru. In this policy, people were given mortgage facility, to be amortised over a period of 15 to 25 years depending on their age and affordability level.82 Buru Buru housing development was a joint venture of the Nairobi City Council, the Kenya Government and the Commonwealth Development Corporation (formerly Colonial Development Corporation). The policy of mortgage housing assumes that the purchaser/buyer has a regular income so that he/she can service the mortgage regularly on a monthly basis. In order to satisfy these policy assumptions, the selection process for potential house owners ensured that there would be minimal risk in owners defaulting on mortgage repayments. This process in the end favoured employees in the formal public and private sectors, and excluded those in the informal sector.83 The hiring of project consultants was the first step to be taken in the project implementation process. The firm; Colin Buchanan and Partners (UK), a foreign firm, was commissioned as the project consultants.84 After commissioning the consultants, the next step in the implementation process was for the project team to design the Buru Buru residential area in terms of ; overall layout, infrastructural services and individual dwelling units. The design, at the very beginning was conceived as phased development 81 Turner, 1976 has argued against treating the housing issue in terms of deficits in numbers to some material standard. He prefers to address the value of housing to people rather than what housing is. See chapter 2. 82 Housing in this case has been treated as a commodity. See for example; Harvey, 1986; Lefebvre, 1979. 83 Informal sector employees were excluded because they generally do not have regular incomes and were therefore potentially risky. 84 Other cities like; Zanzibar, Lusaka, Lilongwe, Dodoma etc. had similar approaches to urban development during the post-colonial period. See Myers, 200: 159. 164 with each phase having approximately 1,000 houses, so that eventually five phases would yield 5,000 houses, housing about 50,000 people as per the project brief. Buru Buru 1970 Buru Buru 1978 Buru Buru 1998 Buru Buru 2003 Fig.5.5, Transformations of Buru Buru – (1970-2003) Buru Buru located some 7km east of the Central Business District (CBD), and lying between Rabai Road and Outer Ring Road, was designed as a middle income residential area on the basis of Western standards. This was because, in newly independent Kenya, according to Richard Stren, housing plans and projects received much national publicity, and on the symbolic level, modern forms were considered appealing. Within this context, modern dwellings for African families were seen as visible evidence of the progress from a colonial society to a modern African State. “By living in more modern structures, it is implied that Africans are themselves more modern” (Stren, 1972). 165 The basis of designing Buru Buru, for the middle income class and to Western standards can also be explained on the basis of Nevanlinna’s study, where she observed that; In Western analyses of newly independent African countries, the middle classes were perceived not only as insurance for continuity, but also as the real motors of development and modernisation. In creating a middle class in Kenya, housing was seen as one of the key elements, particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s. Public housing programmes and development aid policies favoured middle income groups. The notion of dwellings as a vehicle in the creation of a middle class also involved the planning and design of the dwellings (Nevanlinna, 1996:306). Unlike many projects, where potential home owners are consulted for their views on dwelling preferences, no attempt was made to try and get these preferences in the case of Buru Buru. Rather the consultants generated several type plans, starting with a 3-room single storey house to a 5-room double storey house. These proposals were not subjected to any critical debate in terms of their appropriateness as solutions for the housing needs for the emerging African middle class. The impact of this decision can now be felt, and is one of the reasons why many Buru Buru residents are now transforming their houses. Colin Buchanan and Partners were responsible for the design of Buru Buru phase one and two, while phases three, four and part of phase five were designed by Mutiso Menezes International, a local firm. The other part of phase five was designed by Paviz Agepour, another firm practicing in Nairobi. These two later firms continued the trend set by Colin Buchanan and Partners, of developing different type plans, without consulting the potential owners, even when this was possible. Phase one of the developments was completed and occupied between 1973 and 1974, while phase two was completed in 1975. The other phases were completed in 1978, 80 and 83 respectively for phases three, four and five. Buru Buru phase five extensions, built near phase one, and also designed by Mutiso Menezes International was added in 1984. In terms of financing, the Buru Buru scheme was conceived as a mortgage housing scheme, targeting the middle income group as high income groups could fend for themselves without state intervention. Emphasis was laid on individual private home ownership, and therefore individual title ownership. The scheme was tied to a 15 to 20 166 year mortgage, under which the title to each lot was held by the financier/developer, until the mortgage was fully amortised. This individuality, led to the individual lot/plot being the main design/layout generator as can be seen in Fig.5.6, where the lot/plot dominates the whole.85 The plot sizes in Buru Buru are generally 6m x (20-24) m, which allows for a staggered layout that creates internal courtyards. However, the corner plots and those along road reserves tend to be much larger due to the 6-9m building lines stipulated by the building by-laws. The plot sizes are in the ratio of 1:3.3-4, which falls within the efficient ratio of 1:3-4 for optimum service utilisation as developed by Caminos and Geothert, 1978. In Buru Buru, the lot or individual dwelling unit became the generator of the entire neighbourhood. The idea of the individual dwelling unit, acting as the generator of the entire residential area has been addressed by Aldo Rossi, 1982 who posited that the city has always been characterised largely by the individual dwelling. The emphasis on the lot can also be traced to the colonial spatial strategies for enframing order as articulated by Timothy Mitchell. Here the idea was to create a fixed distinction between the inside and outside in domestic architecture and urban design, thereby codifying neighbourhood, family and gender relations in a manner distinct from African systems of domestic order (Mitchell, 1988). 85 By the early 1970s, the emerging African middle class had been partially alienated from traditional rural practices, and was gradually getting assimilated into the Western Capitalist Economy. See chapter 2. 167 R A B A I I S H AN D I S T R I B U TO R S K E N O L P E T R O L STAT I O N DRIVEWA Y R O A D WC/ SH. COURT YARD LOUNGE KITCHEN SH WC LOBBY MUMI AS SOUT H SCALE RAI LW AY CAT H O L I C C H U R C H BARAKA P R I MAR Y S C H O O L R O A D I N S T I T U T E O F F I N E B U R U B U R U AR T R A B A I CHURCH OF JESUS C H R I S T O F T H E LAT E R DAY SAI N T C 0 bedrm . 1 k itc hen sto wc wc p/c opy c yber c afe c yber c afe up dining sto wc 75m kitchen room law n sh / wc hall bedrm . 3 s hw . wc k itc hen liv ing bedrm . 2 bedrm . 1 dining R A I L W A Y dining box cp bd . liv ing C H U R C H O F G O D te a rm. gen ts lad ies PAR KIN G A C C E S S R O A D T O P H. 3 WAIT ING RECE PTIO N REG. TREA TMEN T TREA TMEN T L I N E GATE OFFI CE WC COMP RES SOR GARDEN entra nce entra lobb y nce shop shop shop kiosk M U M I A S U C H U M I S U P E R MA R K E T E A S T A F O F T R I C A H E O L O G N Y servi ce bay wash comp . tyre cl ini c conc rete pave d area sale s oil offi ce male sta ff lpg fe mal e S C H O O L R O A D F LAT S S E R V I C E K O B I L S T A T I O N S O U T H S H O P S & B I D I I MH MALE WCFEMALE WC WC WC LIQ UOR STORE WC SNACK BAR KITCHEN LO UNGE P R I M A R Y MH S H O P P I N G S C H O O L M BUTCH ERY DJ WI NDS C OU NTE R PUB KI TC H . F WCWCWC WC SEATING TE NT S PU B SEATING SEATING SEATING SEATING FLO O R P LA N C E N T R E SH OP BU TC HE R Y H AR D WA R E FOOD KI OSK WC WC WC PLAY STATI ON PLAY STATI ON OFFI C E C HE MI ST 2 C HE MI ST 1 ELE C TRI C AL SH OP H AR D WA R E BA R BE R SH OP WC WC FE MALE MA LE LIQU OR STOR E SN A CK B AR KI TC HE N J IKO LOUN GE C OU NTE R SE ATI NG FLO O R P LA N SA LON C OU NTE R FOOD FOOD KI OSK KI OSK BA R H AR D WA R E FOOD FOOD KI OSK KI OSK BU TC H ER Y TE RR A CE P O S T O F F I C E K E N O L P E T R O L STAT I O N S T . JA M E S D R O A KITCH. A. C. K. C H U R C H SHOP A up ROOM 1 COUNTER BEAUTY SHOP ROOM 2 BUTCHERY T H S O U T O M M B O YA M E M O R IA L HA LL I A S M U M D N li ving box cp bd . bedrm. 1 B MAIN HOUSE STORE BEDRM. BEDRM. ROAD BURU BURU NURSERY SCHOOL ( i )- THE INDIVIDUAL LOT DOMINATES THE WHOLE ( ii )- URBAN EDGE DEFINED BY HEDGE / BUILDING SET BACK JOG OO RO AD 150m 300m LIN E Fig. 5.6, Mumias South Corridor – Partial Layout 168 B U R U B U R U P O LI C E STAT I O N Planning and Development Control Measures Master Planning was the main tool used in the development control of urban areas. As was shown in post colonial Nairobi (chapter 3), all the development control measures for Nairobi and its urban process used the Master Plan. Zoning, density control, height restrictions etc., are used within the Master Plan to parcel certain sections of the city for certain functions. The Master Plan for Buru Buru allowed for a commercial zone to the west of Mumias South Road from phase one to five. This was very similar to the 1948 neighbourhood planning concept articulated by Thornton White et al, who observed that; it is desirable that so far as practicable, there should be an “open space” in the centre of each unit, to be used partly as a recreation space and partly as a reserve for sites for public or semi-public buildings, such as nursery or junior schools, clinics, libraries, clubs etc (Thornton White et al, 1948:64). This central spine was hardly developed, and has been subjected to unprocedural allocations through patronage and clientelism thereby exacerbating informality.86 The specific development control measures that were laid down for Buru Buru included; a density of 32 plots per hectare or 260 persons per hectare, a plot ratio of 75% and plot coverage of 35%. The requirement for car parking was one car per plot and half a car park off plot; houses were to be developed on ground and first floor only. The commercial plots at the shopping centre were zoned for a plot ratio of 200% and ground coverage of 80%; they were also to be built on only two floors. In recent times however, due to the pressure being exerted by alterations, the council has revised the ground coverage for residential plots to 50%, while the plot ratio remains at 75% (discussion with Mr. Mbithi of NCC, 26.08.03). It was also confirmed that no approval has been granted for any double storey extensions, any development beyond ground floor is therefore illegal. It was also envisaged that; there should be no direct access to Mumias South Road; all lots were to be accessed from within the courtyards. Here. Mitchell’s enframing strategy of containerisation and notions of inside/outside came into play, with the Mumias South Road being the outside and the courtyards the inside. This is similar to the 1948 proposal, 86 See Syagga, 2002 for the discussion on land allocation. 169 where Nairobi was divided into some fifty neighbourhood units, which were to be enclosed with a distribution road system (Thornton White et al, 1948).87 Urban Edge Definition The development of Buru Buru housing with a central spine road (the Mumias South Road) presented an opportunity of creating a distinct urbanity in this part of Nairobi. This is because an urban edge is in general defined by the boundary between private space and public space, and depending on how it is articulated; it produces the visual urban images to the walking/driving man.88 Ildefons Cerda` (1855-63), defined the urban edge quite successfully with his Barcelona extension (Eixample) project. In the case of Buru Buru, the building of phase one and two did not allow for a building set back along the central spine road, and the Colin Buchanan and Partners type plans developed for the edge condition, rather than articulate the edge turned their back to it. They occasionally allowed some small windows along the edge, but otherwise the treatment was that of a clear separation of inside and outside Fig.5.7. This further solidified the boundaries between the inside and the outside at the domestic and neighbourhood levels, enhancing containerisation as Mitchell would put it. The general organising principle for the whole housing scheme was to create introverted courtyards from which all houses were to be accessed. These courtyards were interconnected by footpaths allowing the free movement of people; they were also linked to the central spine by footpaths. Over the years, for security reasons and control, these courtyards have gradually been closed off using turnpikes or gates, creating some kind of gated community arrangements.89 The walk through thoroughfares that linked the courts to the central spine, have also been sealed off, now courtyards have only one entry/exit point. The design for phase four and five allowed for a 9m building line/set back along this central spine, this created some challenges in terms of urban edge definition. The designers chose to use a simple wooden fence in defining this edge. Over the years, this 87 This proposal for 50 neighbourhoods was never realised, as no funds were made available for its realisation. Alternatively, the plan could have been a public relations exercise, without any intensions of actualising it. 88 Samuels, I. et al. 2004 discusses this phenomenon as the interface between the house and the city. 89 See Harvey, 1986 and 2000. 170 edge has been the scene for major morphological transformations, thereby completely changing the streetscape/urban morphology of phase four and five in the last 5-10 years. Several building typologies have emerged (Fig.5.8, 5.9 and 5.10), which can broadly be grouped into three categories; commercial, residential and commercial cum residential. The residential type is either used by the extended family or is sublet, while the commercial cum residential is often the type where small enterprises are established on the ground floor with the upper floor being let out as a residential unit. The cases depicting commercial usage only, are actually a complete change of user from residential to commercial e.g. Millennium Dental Clinic and Sunflower Drycleaners, discussed in detail later in this chapter. Fig.5.7, Urban Edge Definition 2 – Phase 1 171 Fig.5.8, Commercial Transformation Fig.5.9, Residential Transformation Because of the uncoordinated nature of these transformations, it is difficult to predict what kind of urban edge will result, as they take place on an individual basis depending on the ability and preferences of the plot owner. It would have made a better visual impact had this edge been defined at the design stage i.e. building up to the plot boundary and leaving enough road reserve for infrastructural services. It seems prudent to suggest that options in design typologies should have allowed for small enterprises to evolve along the corridor, making it more inclusive and commercial in outlook. Fig.5.10, Commercial cum Residential Transformations 172 It would have been possible to design the dwelling such that small enterprises could open directly to the street on two levels, with a possibility of lettable rooms on the third level. This would then fix the urban edge condition, which would reduce the possibilities of future modifications. The main dwelling at the rear could also be designed for phased development, building a few initial rooms, and allowing room for future extensions Fig.5.11. By articulating the urban edge and creating possibilities for morphological transformations to happen, amore harmonious urban fabric would have been the likely result.90 For example Cerda’s urban block in the Barcelona extension, has undergone morphological transformations for more than 140 years, but still retains its historical aesthetics/character. 90 173 Fig.5.11, Urban Edge Definition 3 174 Informalising the Formal Mumias South road is the main circulation spine through the Buru Buru housing development, which forms a major motorised communication corridor. It was meant to have commercial facilities and community amenities along it. However, during the implementation stage, only a few shops and one restaurant were built, while the provision for other amenities such as cultural centres, markets, library etc., were never realised. This omission facilitated the ad-hoc development process taking place along this corridor; it also has enabled the clientelism and manipulation by the power elite in the subdivision and allocation of commercial plots. The character of the corridor has changed drastically in the last 5-10 years due to the morphological transformations that have taken place. New hybrid urbanity is therefore emerging, where three basic urban types can be identified; commercial, residential and commercial cum residential. There are approximately 250 plots adjoining the Mumias South Road, between Rabai road and Buru Buru police station a distance approximately 2km long Fig.5.6. Some of the plots which were large and meant to be reserved for social facilities/amenities are now subjected to further subdivision including change of user for some open spaces. More than 50% of all properties (buildings) in this corridor have undergone some morphological transformation. The majority of these transformations have resulted in small business outlets; hair salons, cyber cafes, wines and spirits, butcheries, fast foods, clinics etc., plus of course residential extensions. What is also characteristic about this process is that there is an intensity of built form transformation at road junctions within the corridor Fig.5.12 Fig. 5.12, Layout – Cluster A 175 30M WIDE MUMIAS SOUTH ROAD 285 195 286 box c pbd. 287 194 sto 196 284 living 194 kitchen wc bedrm. 1 dining 197 18M ROAD 283 198 199 kitchen box c pbd. bedrm. 1 wc 281 COURT sto living dining 282 200 280 COURT dining kitchen living 279 hall 201 wc bedrm. 1 shw. bedrm. 3 bedrm. 2 202 AS DESIGNED ( 1975 ) 30M WIDE MUMIAS SOUTH ROAD 285 195 286 box c pbd. 287 194 p/copy kitchen 284 196 cyber cafe wc living dining 197 18M ROAD 283 wc kitchen box c pbd. bedrm. 1 199 sto living dining 281 198 up 282 COURT 194 cyber cafe sto wc bedrm. 1 200 280 COURT sh / wc dining kitchen living room 279 hall wc shw. 201 bedrm. 1 lawn bedrm. 3 bedrm. 2 202 AS BUILT ( 2004 ) SCALE. 0 10m 20m 40m Fig.5.12b, Phase 4 Junction - Cluster A Layout 176 Commercial Transformations These are transformations where the premises either partially or wholly changes use, as can be seen in the transformations on plots 2/496, 2/858 and 4/174, represented by Figs.5.13, 5.14 and 5.15 respectively. The transformations on plot 2/496 have left the original residential house intact, by the building of a new structure fronting the Mumias South Road. The new structure has six lettable rooms on ground and first floors, with the first floor rooms opening onto a balcony that cantilevers to the street Fig.5.16. The materials used in building the new structure are similar to those of the original construction, so it tends to blend into the context; however, it creates a new street character by orienting towards the street and breaking away from the original containerisation principle of inside/outside.91 The position of the new construction is about 1m away from the original house, which compromises the lighting conditions to two of the rooms on the original house i.e. bedrooms 2 and 4, and the rental rooms in the new structure Fig.5.13. The new structure obviously impacts on the carrying capacity of the sewer, water and power supply. Another feature of the new construction is the use of the A-frame as opposed to the lean to hollow pot roof construction originally used. Many local artisans (fundis) are not familiar with hollow pot construction, and therefore opt for the more common timber A-frame construction. Even if they were to be knowledgeable on hollow pot maxi-span construction, it would be uneconomical to build only one unit using this system. Four of the rooms in the new structure are let out as; grocery shop, beauty shop, barber shop and hair saloon, with the remaining two rooms being let out as rental rooms. These small businesses create jobs for some 8 people and generate a monthly rental income of about Kshs 25,000 ($ 312.5) for the landlady. Assuming the new structure cost Kshs 1,200,000 ($ 15,000) to build, the payback period at the above rental income is about 48 months, which is a short enough period to justify the investment, as average pay back period for such investments is normally in excess of 120 months. 91 For a discussion on the notion of containerisation, see Mitchell, 1991. 177 bedrm. 2 bedrm. 1 TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE bedrm. 4 living rm. A A SECTION A - A A TIMBER FENCE bedrm. 3 dining 1 8 M. R O AD RESERVE bedrm. 1 living bath kitchen wc bedrm. 4 A bedrm. 2 A FIRST FLOOR PLAN A GROUND FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1975 ) 30 M. MUMIAS SOUTH R O A D USE OF A - FRAME AS OPPOSED TO LEAN TO HOLLOW POT CONSTRUCTION STONE WALL FENCE balc. salon office shop shop STONE WALL FENCE MUMIAS SOUTH ROAD ELEVATION 01 A A SECTION A - A STONE WALL FENCE 1 8 M. R O AD RESERVE up WC/ SH WC/ SH RENTAL RM BEAUTY SHOP BARBER SHOP SHOP RENTAL RM SALON HSE. NO. 495 ( i ) USE OF A- FRAME ROOF ON EXTENSIONS. FIRST FLOOR PLAN A A GROUND FLOOR PLAN SCALE. 0 TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) 30 M. 4.5m 9m 18m MUMIAS SOUTH R O A D Fig.5.13, Transformations on 2/496 178 The transformations on plot 2/858, are a complete change of use from residential to drycleaning, a semi-industrial activity. The resultant layout of this transformation is not sensitive to fundamental design issues. First of all, the new toilet and office next to the laundry machine have their windows opening directly to the adjacent plot, which is not acceptable. Secondly, nearly all the internal rooms i.e. store, yard/store and meeting room have no natural lighting, and have to rely on the unpredictable artificial lighting Fig.5.14. The resultant built form creates plot coverage of about 75% and a similar plot ratio, well above the allowable design ratio of 35%. The extensions also use alternative materials i.e. corrugated galvanised iron (cgi) roofing sheets as opposed to clay tiles and timber walling as opposed to masonry thereby creating a visual conflict. Another peculiar development on this property is the annexing of the 3m public passage (a practice commonly referred to as land grabbing), for private use.92 It is a known fact that nearly all the public passages to the spine road have been closed for security reasons, but this should not be license for some individuals to annex these passages for private use. This type of transformation (semi-industrial) puts a lot of pressure on infrastructural services, particularly water and power supply. This pressure according to the proprietor, forced him to install a three phase power supply system to be able to cope with the power demand of this semi-industrial enterprise. Although the water supply to this enterprise was said to be stable, the monthly payments showed that the consumption was quite high. The payments were Kshs 30,000 ($ 375) for electricity and Kshs 9,000 ($ 112.5) for water. These are more than the payments average domestic consumers make of Kshs 2,000 ($ 25) and Kshs 1,500 ($ 18.75) for electricity and water respectively. The costs involved in carrying out this business are also not small; they include a monthly rent of Kshs 19,000 ($ 237.5), a monthly wage bill of approximately Kshs 40.000 ($ 500), annual city council license fee of Kshs 15,000 ($ 187.5), plus Kshs 10,000 ($ 125) per month for security guards. The landlady/tenant relationship is not on a contract basis as the original five year lease lapsed in 1998. Currently they are operating on an informal basis (gentleman’s agreement). A case in point is that; recently (2001), the landlady allowed the tenant to construct the timber extension at a cost of Kshs 30,000 ($ 375). The enlarged business 92 See Syagga, 2002. 179 premise creates employment for 11 people, jobs which the formal sector would otherwise not have created. TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE 3.0 M PASSAGE 30.0M MUMIAS SOUTH ROAD COURT SECTION A - A B SECTIONAL ELEVATION 01 6.5M SET BACK TIMBER FENCE kitch. back yard TIMBER FENCE living rm. wc sh COURT 30.0M bedrm. 2 bedrm. 1 parking A gate MUM IA S S H RO OUT A 3.0 M PASSAGE AD B FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION ( 1975 ) G.C.I. ROOFING SHEETS G.C.I. ROOFING SHEETS STONE WALL FENCE AND METAL GATE 30.0M MUMIAS SOUTH ROAD drying/ storage storage storage COURT SECTION A - A B SECTIONAL ELEVATION 01 laundry machine wc off. store yard/sto. storage meeting rm. wc office washing/drying machine rm. 30.0M MUM reception display IA S S pressing rm. storage car park A ( i ) USE OF ALTERNATIVE MATERIALS ON EXTENSIONS. H RO OUT ( ii ) OPENING WINDOWS TO PRIVATE PROPERTY drying / storage A B AD ( iii ) ANNEXING 3.0M PUBLIC PASSAGE FOR PRIVATE USE. FLOOR PLAN SCALE. 0 3m 6m 9m 15m TRANSFORMED CONSTRUCTION ( 2004 ) Fig.5.14, Transformations on 2/858 180 sh / wc TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE dining 6.0 M ROAD 6.0 M ROAD A SECTION A - A 30 M. R O H UT SO S A MI MU A A ELEVATION 01 A D RVE RESE ROAD kitchen sto wc bedrm. 3 hwc bedrm. 1 01 box c pbd. TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE living dining bedrm. 2 yard sh/wc GATE BUILDING LINE FIRST FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1978 ) A A GROUND FLOOR PLAN sh / wc MASONRY COLUMNS AND STONE WALL FENCE MASONRY COLUMNS AND STONE WALL FENCE 6.0 M ROAD dining 6.0 M ROAD SECTION A - A 30 M. A MI MU S U SO TH R O A A ELEVATION 01 D A E SERV RE ROAD STONE WALL FENCE MASONRY COLUMNS AND STONE WALL FENCE GARDEN RECEPTION PARKING REG. OFFICE 01 WC WAITING TREATMENT OFFICE roof over car port OFFICE TREATMENT COMPRESSOR GATE A TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) WC/ SH. FIRST FLOOR PLAN A GROUND FLOOR PLAN OFFICE SCALE. 0 4.5m 9m 18m Fig.5.15, Transformations on 4/174 181 The above laundry business also indicates that people are willing and able to invest large sums of money informally due to the prevailing socio-economic circumstances. The architectural character resulting from these transformations is however doubtful, as there is a clash of building material usage, and many rooms having to rely on artificial lighting. As discussed earlier, here again is a situation where a flexible initial design would have allowed for more appropriate morphological transformations to occur (See, Fig.5.11). Although the annexing of the adjacent passage way seems to improve the security in the area, it needs to be regularised. Figs.5.17, 5.18 and 5.19 show some images of these transformations on plot 2/858. Fig.5.16, Balcony on 2/496 The other significant commercial transformation in the corridor is the Millennium Clinic on plot 4/174. This commercial enterprise is a dental clinic, which caused the previous residential quarter to be converted into a health facility Fig.5.15h. The whole ground floor of the original house has been transformed to suit dental operations including the addition of a new waiting area. The upper floor has remained more or less the same 182 except for the addition of an office space on top of the original kitchen and toilet below. The use of building materials and the general architectural language is similar to the original construction, thereby making the new blend into the original context. Fig.5.17, Drying Area 2/858 Fig.5.18, Annexed Passage Adjacent to2/858 Fig.5.19, Entrance - Drycleaners 2/858 Plot 4/174 is one of the larger corner plots measuring approximately 360m² and where a 6m building line was allowed from the spine road. The transformations from a house to a clinic resulted in increasing the plot coverage, however, even with this increase; the coverage is still less than 30%, although the allowable coverage is 35%. This is another 183 condition where the by-laws have to be re-looked at. There is no need of having these large individual corner plots due to building lines and set backs yet the road reserves are quite generous. In the last 25 years since Buru Buru phase four was completed, nothing much has happened within these large road reserves, and nothing is likely to happen in the foreseeable future. It would therefore make economic and design sense by rationalising the urban edge condition by for example having a zero building line. This would increase the number of houses per hectare, and also create an opportunity to properly define the urban edge by the building mass. The original timber urban edge definition was changed to a stone wall construction and at the same time the outside/inside divide was violated by creating a pedestrian entrance directly from the Mumias South Road. The well kept planting along the road, conceals the harsh/greyness of the boundary wall. Figs.5.20, 5.21, 5.22 and 5.23 show some images of this clinic. The Millennium Clinic, apart from increasing the power consumption slightly, pretty much functions as the average residential house, and therefore puts little pressure on the infrastructural facilities. Fig.5.20, Clinic Access 4/174 Fig.5.22, Entrance Area 4/174 Fig.5.21, Dental Room 4/174 Fig.5.23, Reception 4/174 184 Residential Transformations Residential transformations have taken place mainly due to family dynamics, and can either be entirely driven by the extended family requirements or by economic demands. Either way the transformations impact on the urban fabric both visually and by putting additional pressure on urban infrastructural services. The transformations on plot 4/201 are an example of those being driven by the extended family requirements, and where cultural practices demand that adult sons do not share the same roof with their fathers (discussion with owner, 01.01.04). The owner, who has lived in this house since 1981, is father to two adult daughters and one adult son. The need to house the adult son in a separate dwelling is the main reason behind the transformation. Fig.5.24 shows how the extensions have been realised, with a new private family yard and a lawn to the rear resulting from the transformation. The containerisation syndrome as articulated by Mitchell, 1991 is also ignored by the creation of a new access directly from the external distributor road Fig.5.27. This allows the adult son to access his self-contained room, freely without disturbing people in the main house. For acoustic and visual privacy, the extension is detached and has a separate roof from the main house’s (father’s) roof. In the event that the adult son migrates, the selfcontained room can be sublet to an outsider. Figs.5.25, 5.26 and 5.27 show some images of this transformation. The original house had a plot coverage of 30%, which was just below the allowable coverage of 35%, while the coverage after the transformation is now 37%. In addition to the increased density, the new extension will of course put pressure on the water; sanitation and power supply systems, even though these services are now adequately catered for. The resultant architectural character is simple and well controlled; however, concrete roofing tiles are used instead of the original clay tiles. The use of a timber roof construction also contrasts the maxi-span system originally used. This can be attributed to the technological limitations of the local artisans (fundis) and the economies of scale involved in building a small 20m² extension. Like other transformations in the corridor, the plans for this extension have not been approved by the council. This extension including minor alterations to the main house was built on a labour contract at the cost of approximately Kshs 500,000 ($ 6,250). 185 TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE hall sh/wc bedrm. 6.0 M ROAD COURT SECTIONAL ELEVATION Y - Y Y ROAD 6.5M SET BACK TIMBER FENCE dining WIDE kitchen hall wc bedrm. 1 shw. 15 . 0 M Y TIMBER FENCE living GATE bedrm. 3 bedrm. 2 dustbin cubicle FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION ( 1980 ) MAREBA ROOF TILES ON TIMBER RAFTERS STONE WALL FENCE PURPOSE MADE GLAZED STEEL CASEMENT WINDOWS pv pv sh/wc hall bedrm. COURT 6.0 M ROAD SECTIONAL ELEVATION Y - Y shop shop wd room sh / wc STONE WALL pv yard pv pv pv p.c.c paviours Y lawn 15 . 0 M WIDE ROAD Y GATE STONE WALL dustbin cubicle FLOOR PLAN TRANSFORMED CONSTRUCTION ( 2004 ) SCALE. 0 3m 6m 9m 15m Fig.5.24, Transformations on 4/201 186 At the time of the study (January, 2004), the 20 year mortgage had been fully amortised, and the only payments being made by the owner, were the annual land rate of Kshs 5,000 ($ 62.5) and land rent of Kshs 1,000 ($ 12.5). On top of these payments each household pays a monthly sum of Kshs 400 ($ 5) for watchmen (Askaris) who provide a 24 hour private security service plus Kshs 150 ($ 1.875) for private refuse disposal. This example shows a clear case where traditional civic responsibilities have been privatised, the question then to be posed here is; what are the land rents and rates being paid for? May be these rates are too low to have any impact in enhancing the council’s financial capacity to deliver services. With regard to house types, the owner of this property (plot 4/201), would have preferred a double storey house. However, due to the lottery nature of allocation, he had to make do with the bungalow, otherwise given better economic circumstances; he would migrate to a more up-market neighbourhood. This is a case as discussed earlier of a mismatch between people’s needs and design options, which could have been resolved at the design stage. Fig.5.25, Entrance View 4/201 Fig.5.26, Lawn/Drying Area 4/201 On the other hand residential transformations which have been driven by economic considerations are those on plot 5/437. These transformations have basically flouted the 9m building line requirement, but have remained within the allowed plot ratio and coverage. After completing the transformations, the plinth area was increased from the original 84m² to 184m². This changed the density on the plot from the original plot ratio of 19.5% to 59%, while the original plot coverage of 10.5% increased to 34% Figs.5.28 and 5.29. This low coverage even after increasing the plinth area by more than 100% can 187 be attributed partly to the fact that plots adjoining the central spine measure approximately 400m², while the average plot is about 150m². The other reason could be that the property owners are willing to increase the density by building extensions, but within the council’s by-laws and without building on public land. In effect they are making a direct critique of the validity of the 9m building line along the central spine. Fig.5.27, View from Access Road 4/201 These transformations like all others, put pressure on the infrastructural services. Although water supply and the sewage system have performed rather well over the years, there is water rationing from time to time. The supply of electricity is now adequate, otherwise during the 1999 rationing period, a stand by generator had to be bought, necessitating the building of the store/generator room next to the main house. In order to minimise the tenant/landlady conflicts, each of the three sub-tenants have their separate water storage tanks, water and electric meters. A separating stone wall also gives the extensions their privacy and reduces the possibility of conflicts. 188 TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE 7.0M ROAD ROAD RESERVE A A COURT FRONT ELEVATION 30M WIDE MUMIAS SOUTH ROAD 9.0M BUILDING LINE TIMBER FENCE BATH BEDRM. 4 SH. up DINING PORCH KITCHEN DRIVE WAY WC LOUNGE BEDRM. 1 BEDRM. 3 BEDRM. 2 FIRST FLOOR PLAN GROUND FLOOR PLAN TIMBER FENCE A ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1982 ) KITCHEN SH KITCHEN SH A ( i ) USEOF A - FRAME CONSTRUCTION ON EXTENSIONAS OPPOSED TO MONO-PITCH HOLLOW POT CONSTRUCTION ( ii ) BUILDING BEYOND THE BUILDING LINE BUT WITHIN THE PLOT. STONE WALL FENCE STONE WALL FENCE 7.0M ROAD ROAD RESERVE COURT A A SECTIONAL ELEVATION A - A 30M WIDE MUMIAS SOUTH ROAD 9.0M BUILDING LINE B B KITCHEN BEDRM. LOUNGE LOBBY BEDRM. WC KITCH. WC/ SH. ROOM 1 ROOM 2 B B roof over 1 bedrm. unit KITCHEN BEDRM. COURT YARD LOUNGE LOBBY SH BEDRM. WC SH DRIVE WAY STONE WALL STORE GROUND FLOOR PLAN roof over store STONE WALL FIRST FLOOR PLAN TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) 3.5m 7.0m 10.5m 17.5m A 0 A SCALE. Fig.5.28, Transformations on 5/437 189 ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1982 ) TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) SCALE. 0 3.5m 7.0m 10.5m 17.5m Fig.5.29, Original and Transformed Constructions 5/437 190 In terms of the resultant built form character, here again the morphological transformations tend to blend within the overall context as adjoining properties are also being transformed Fig.5.30. As mentioned before, timber roof construction is the preferred method in the extensions rather than the maxi-span system originally used, and concrete roofing tiles are preferred to clay tiles. These choices result mainly from the advice given by the local fundis, who are technologically familiar with the use of the materials they recommend. It cost approximately Kshs 1,700,000 ($ 21,250) to build the extensions on lot 5/437, which is quite a high investment relative to Nairobi standards in 1998 when this work was carried out. Although the three units (two flats and a bungalow) were meant to be all residential, the one bed roomed bungalow has been let out as a hair saloon. This is because the location of the plot is preferred by small businesses which pay more money than when used for residential purposes Fig.5.31. These rental units, fronting the central spine road are accessed directly from this road, giving a sense of privacy to both the tenants and the main household. The three units generated a monthly rental income of Kshs 37,000 ($ 462.5) to the main household as at December 2003. This income ensures a guaranteed source of money for the household in a system where social security is weak and retirement benefits are not assured. In this particular case, both parents in the main household are retirees; one of them was retrenched as a result of the application of SAPs. It is the golden handshake funds from retrenchment that were used in building the extensions.93 Fig.5.30, View from Spine Road 5/437 93 Fig.5.31, Interior – Hair Saloon 5/437 See the story of Adhiambo in chapter 4 – Primary Informalities. 191 It is worth noting that this property, bought in 1983 for the sum of Kshs 290,000 ($ 29,000) had been fully paid for by 1998. The household pays annually land rates and rent of Kshs 6,000 ($ 75) and Kshs 425 ($ 5.3). Garbage collection is privatised at the rate of Kshs 200 ($ 2.5) per household per month, while security is another expense, and according to the lady of the house; The proximity of the property to the main road makes it insecure as the police force is ineffective. We had to fence with an electric fence and barbed wire on the perimeter wall; we also had to install an indoor alarm system. Those who use group security (watchmen/Askaris) pay Kshs 200 ($ 2.5) per household per month. (Discussion with landlady, 15.12.03). Fig.5.30 shows the barbed wire and the fence on top of the boundary wall facing the spine road. The other attribute to this development, is that being at the corner of the court, it has ample car parking space Fig. 5.32. In these transformations, the original four bed roomed house has remained unchanged except for the addition of a small store/generator room at the rear of the house. Owners are willing and able to risk large sums of money in building informally. Also, contrary to a common belief that there are no rules in informal transformations, there seems to be a common agreement on double storied extensions among all the residents within the corridor Fig.5.34. A three storey construction in the vicinity was demolished due to pressure by area residents; this construction is currently turning into a ruin Fig.5.35. Fig.5.32, Ample Car Parking 5/437 192 S SOUTH ROAD COURT 30M WID E MUMIA MAIN HOUSE DRIVE WAY MAIN HOUSE WC STORE BEDRM. BEDRM. LOBBY SH KITCHEN LOUNGE COURT YARD WC/ SH. KITCH. ROOM 1 ROOM 2 AS DESIGNED ( 1975 ) AS BUILT ( 2004 ) SCALE. 0 10m 20m 40m Fig.5.33, Transformations - Cluster B 193 Fig5.34 Cluster B, Double Storey Exts. Fig.5.35. Demolished 3- Storey Ext. Residential cum Commercial Transformations These transformations are driven by the commercial needs of creating small enterprise outlets and lettable small apartments. The developer on plot 4/282 acknowledged that he wanted to take advantage of the “market potential” since his plot is strategically located at a major junction within the corridor Fig.5.12. Typically these transformations take the form of a double storey structure opening to the road, with the ground floor and upper floor being let out separately. The development on plot 2/814 has a one bed roomed apartment on the ground floor and a video library on the upper floor, accessed via external stairs Figs.5.36 and 5.37. In order to create privacy to the main house, a solid wall with a metal gate has been built separating the extension from the main house. Like other extensions, the new structure puts additional pressure on the infrastructural services, and also increases the density of the development, creating plot coverage of over 50%. The character generated by the extension contrasts with the general milieu, but because the adjacent properties use a similar typology in their extensions, a new language has evolved creating its own uniqueness Fig.5.38. The consistent use of a mono pitch lean to roof and the use of a timber roof structure deviate from the original construction system as earlier discussed. In terms of income generation and job creation, the video library employs one person and generates a rental income of Kshs 9,000 ($ 112.5) per month for the landlord. The tenant pays for the privatised garbage disposal service and the night time security at the rate of Kshs 150 ($ 1.875) and Kshs 300 ($ 3.75) per month respectively. To reduce the 194 tenant/landlord conflicts, the tenants pay their own electricity and water bills, while the landlord pays all statutory payments. bedrm. 1 bedrm. 2 TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE 6.0M ROAD COURT SECTION A - A bedrm. 1 A bedrm. 2 A wc COURT bedrm. 3 bath FIRST FLOOR PLAN 9.0M SET BACK TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE living dining BACK YARD COURT kitchen GATE wc 18.0 MW yard ( i ) USE OF WOODEN FENCE AND GATE A IDE ROA D A GROUND FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1975 ) ( i ) USE OF STONE WALL ON BOUNDARY AND STEEL GATES STONE WALL FENCE STONE WALL FENCE STONE WALL FENCE 6.0M ROAD COURT SECTIONAL ELEVATION A - A A A VIDEO LIBRARY COURT room 2 sh/wc room 1 kitch FIRST FLOOR PLAN STONE WALL FENCE A yard STONE WALL FENCE ( i ) USE OF STONE WALLON BOUNDARY AND STEEL GATE bedrm. living sh/wc IDE ROA D COURT kitch 18.0 MW A GROUND FLOOR PLAN TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) SCALE. 0 3m 6m 9m 15m Fig.5.36, Transformations on 2/814 195 On this particular property, the ground floor tenant was exempted from any payments, since she was the daughter of the landlord, who needed her independence without being far from the family home. This extension was therefore quite appropriate. Although these transformations may be considered illegal in the eyes of the city planning department, they gain legitimacy through the council’s own water department, which has officially supplied water to them. The extensions are further legitimised by the Kenya Power and Lighting Company, which has made official power supply. Fig.5.37, Video Library 2/814 Fig.5.38, New Architectural Character The transformations on plot 4/281 create two small shops on the ground floor and a one bed roomed apartment on the upper floor Fig.5.39. From a design point of view, the placement of the new structure, compromises the privacy of the kitchen in the main house including blocking the stair window. The combined effect of the transformations on plots 2/281-284 creates a tunnel effect between the main houses and the extensions Figs.5.12 and 5.40. This may cause a Banuli effect in case of high winds, which can damage the roofs and the general building fabric. It is evident that the transformations on the four plots all have balconies that cantilever beyond the plot boundaries and into the road reserve, as required by the building by-laws. This is a good example of the interface of informal and formal practices Fig.5.41.94 The landlord on 2/281, who has lived with his family on this property for more than twenty years, carried out the transformations in 1999, when the mortgage had been fully amortised. It cost in excess of Kshs 1,000,000 ($ 12,500) to build these extensions, which 94 See for example; De Soto, 2001; Hansen and Vaa, 2004, for the discussion on the interface between the formal and the informal. 196 generate a combined monthly income of Kshs 15,000 ($ 187.5). This rental income is rather low for the size of extensions; this is partly because the landlord’s wife runs one of the ground floor shops as a Home Based Enterprise (HBE), and does not pay rent for use of the shop. It is important to re-emphasise that the transformations were necessitated in order to capture the market potential for subletting, through which a regular income can be guaranteed. Another transformation on plot 4/284, has a cyber café on the ground floor and a hair salon upstairs Figs.5.42, 5.43 and 5.44. The cyber café which started operating in 2001 generates employment for three people on a full time basis and one person on a part-time basis. The café pays the landlord a monthly rent of Kshs 12,000 ($ 150), while the electricity bill of about Kshs 6,000 ($ 75) per month for the whole property is shared on a 50-50 basis between the landlord and the tenants. The water bill of approximately Kshs 1,500 ($ 18.75) is paid for in a similar manner. The café pays an annual trade license fee of Kshs 10,000 ($ 125), while the landlord makes the other statutory payments. Mumias South Road as a transport spine, creates a very good catchment area for the cyber café, which serves about 80-120 customers per day. The hair saloon on the upper floor pays a monthly rent of Kshs 10,500 ($ 131.25), while the water and electricity bills are shared with the cyber café as earlier discussed. Similar to the café, an annual trade license fee of Kshs 10,000 ($ 125) is paid. The business which creates jobs for three people has ample space to serve 6-10 clients per day. It required in excess of Kshs 100,000 ($ 1,250) worth of investment to start the saloon, which had operated for 2.5 years by December 2003. It can be argued that the cyber café similarly required an initial investment capital in excess of Kshs 300,000 ($ 3,750) to start operating with six work stations.95 From the foregoing, it is clear that some of these small enterprises require a sizeable sum of money for the initial investment. They can be seen as illegal in the eyes of city planners, they however create job opportunities for many people, and also create a steady income for landlords. The fact that many have been operating for a while without closing means that they are sustainable, and could benefit by being incorporated in formal systems/operations. 95 See chapter 4, Table 3. 197 bedrm. 2 wc/sh TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE living dining yard 6.0 M ROAD SECTIONAL ELEVATION bedrm. 3 hwc bedrm. 2 kitchen wc W I DE ROAD bedrm. 1 TIMBER FENCE sto GATE FIRST FLOOR PLAN box c pbd. A sh/wc BACK YARD COURT living A dining 15 . 0 M TIMBER FENCE GROUND FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1980 ) CONC. ROOF TILES ON TIMBER RAFTERS EX. TIMBER FASCIA BOARD PAINTED TO APPROVAL pv kitch. bedrm. 2 STONE WALL ( i ) USE OF A - FRAME AS OPPOSED TO LEAN TO HOLLOW POT CONSTRUCTION balc. pv PURPOSE MADE GLAZED STEEL CASEMENT WINDOWS shop COURT 6.0 M ROAD SECTIONAL ELEVATION pv pv room 2 pv balcony dn pv pv wc/sh pv pv room 1 up GATE pv pv pv shop pv pv A 15 . 0 M 6,000 COURT W I DE ROAD FIRST FLOOR PLAN pv shop pv 6.0M BUILDING LINE room GROUND FLOOR PLAN pv TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) SCALE. A 0 3m 6m 9m 15m Fig.5.39, Transformations 4/281 198 Fig.5.40, Narrow Gap Between Old and New (Tunnel effect) Fig.5.41, Cantilevered Balconies 199 bedrm. 2 wc/sh TIMBER FENCE TIMBER FENCE living dining TIMBER FENCE yard COURT 6.0 M ROAD SECTION A - A A A sh/wc hwc bedrm. 2 COURT W I DE ROAD bedrm. 3 FIRST FOOR PLAN 6.0M SET BACK 6.0M BUILDING LINE A dining A TIMBER FENCE GATE bedrm. 1 box cpbd. wc COURT 15 . 0 M living sto TIMBER FENCE kitchen ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1980 ) GROUND FOOR PLAN ( i ) USE OF A - FRAME TIMBER TRUSS ON EXTENSIONS office balc. STONE WALL FENCE new room COURT 6.0 M ROAD SECTION A - A 6.0 M SET BACK A A office COURT W I DE ROAD salon balcony wc FIRST FOOR PLAN A 15 . 0 M new room STONE WALL FENCE wc A rm. 2 COURT cyber cafe GATE p/ copy GROUND FOOR PLAN TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) rm. 1 SCALE. 0 3m 6m 9m 15m Fig.5.42, Transformations on 4/284 200 Fig.5.43, Interior – Cyber Café 4/284 Fig.5.44, Interior – Hair Saloon 4/284 201 ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1980 ) TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 1992 ) TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) SCALE. 0 3m 6m 9m 15m Fig.5.45, Phased Transformations 4/284 202 Transformations of the Shopping Centre The Buru Buru shopping centre lies within the corridor in what was originally conceived as the commercial and social amenities zone, on the western side of the corridor. The centre was initially designed to have 20 double storey shops and two restaurants, but only 11 shops and one restaurant were built during the implementation phase Fig.5.47. This action, on the on set created pre-conditions for subsequent informal commercial developments during the consolidation phase of the estate. Currently many informal outlets have sprung up within the corridor to fill the gap left by the initial inadequate shopping provision. A large market has evolved on the footpath linking Buru Buru and Umoja estates, commonly known as Mutindwa Fig.5.46. The shops and restaurant that were built 30 years ago have also undergone morphological transformations over this period with nearly all the shop balconies being converted into internal spaces Fig.5.48. Many commercial outlets have also engulfed the one restaurant originally built, now commonly known as the “Mausoleum”. I now discuss the transformations that have taken place on the “Mausoleum” to some detail. Fig.5.46, Shopping Centre 2003 (Informal Market – bottom left) 203 WC WC WC WC BUTCHERY 4.5M WIDE SERVICE ROAD POST OFFICE BUTCHERY MH WC SNACK BAR KITCHEN LIQUOR STORE MH WC WC LOUNGE MALE WC FEMALE WC SHOPPING CENTRE MH WC SNACK BAR KITCHEN LOUNGE COUNTER LIQUOR STORE WC MH MALE WC FEMALE WC WC 30M WI DE MU MIAS SO UTH RO AD AS DESIGNED ( 1975 ) WC WC WC WC BUTCHERY 4.5M WIDE SERVICE ROAD POST OFFICE BUTCHERY WC SHOPPING CENTRE SNACK BAR KITCHEN MOSOLEUM TERRACE LIQUOR STORE WC MALE WC FEMALE WC WC 30M WI DE MU MIAS SO UT H ROAD AS BUILT ( 1975 ) 4.5M WIDE SERVICE ROAD COUNTER WC WC WC WC BUTCHERY TENTS PUB SEATING POST OFFICE SEATING F M KITCH. SEATING WINDS PUB DJ SEATING BUTCHERY FOOD KIOSK FOOD KIOSK BUTCHERY SEATING JIKO CHEMIST 1 BUTCHERY WC HARDWARE SHOPPING CENTRE SNACK BAR KITCHEN MOSOLEUM TERRACE WC MALE WC BAR FEMALE WC COUNTER CHEMIST 2 OFFICE LIQUOR STORE WC PLAY STATION PLAY STATION BARBER SHOP SHOP FOOD KIOSK FOOD KIOSK SALON 30M WI DE MU HARDWARE FOOD KIOSK ELECTRICAL SHOP HARDWARE MIAS SO UT H ROAD AS BUILT ( 2004 ) SCALE. 0 20m 40m 80m Fig.5.47, Cluster D - Shopping Centre Transformations 204 Fig.5.48, External Balconies Internalised Fig.5.49, Informal Market – Mutindwa Thoroughfare 205 Transformations of the “Mausoleum” The “Mausoleum” originally designed by Colin Buchanan and Partners in 1975, as one of the two identical bar and restaurants, has been gradually transformed informally so that we now have an additional 20 subtenants renting peripheral extensions from the main restaurant owner Fig.5.50. These extensions generally use alternative building materials e.g. c.g.i roofing sheets as opposed to clay tiles and block board or sheet metal as opposed to masonry walling. These extensions have put a lot of pressure on the sanitary facilities and the water and power supply to the “Mausoleum”. The original yard to the kitchen of the restaurant has been built up, blocking the natural lighting and ventilation to the kitchen and toilets. These 20 subtenants create job opportunities for many unemployed people and also generate an income for the restaurant owner. More than 40 jobs have been created by these transformations; as a result the restaurant owner earns a monthly income in excess of Kshs 100,000 ($ 1,250). Ukweli Fabricator and General Hardware is one of the 20 subtenants Fig.5.51. The proprietor of this business, who is a qualified welder/fitter, started the business on the current site in 2002 after relocating from elsewhere. He had earlier been retrenched in 1992, when SAPs of right sizing were invoked by his previous employer.96 He opted to venture into the Jua Kali sector, and currently has a work force of 6 people. These employees are paid on a weekly basis at the rate of Kshs 300 ($ 3.75) for a fundi per day while the mtu wa mukono (casual labourer) is paid Kshs 200 ($ 2.5). The foreman is paid Kshs 9,000 ($ 112.5) per month. This business pays kshs 10,00012,000 ($ 125-150) per month for rent and electricity. There is only one meter for the restaurant and all the 20 subtenants, so they have agreed to share the electricity payment. In order to secure the premises, particularly during the night, watchmen are hired by tenants who each pay Kshs 250 ($ 3.125) per month. This case of Ukweli is an example of how most tenants operate.97 It was also observed that most of these businesses have been operational for the last five years or so and are generally stable. Like most other small enterprises, they pay the local authority annual trade license fees, thereby gaining some form of legitimacy. 96 This situation is similar to that of Adhiambo (Chapter 4), and is also similar to that discussed in residential transformations. 97 The formation of peer group associations is discussed by De Soto, 2001. 206 LIQUOR STORE LOUNGE SOUTH ELEVATION SECTION A - A WC SNACK BAR KITCHEN LOUNGE BAR LIQUOR STORE WC SERVICE YARD MALE WC FEMALE WC WC FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1975 ) SOUTH ELEVATION FOOD KIOSK 19 18 FOOD KIOSK BUTCHERY SEATING 20 JIKO CHEMIST 2 1 BUTCHERY store CHEMIST HARDWARE HARDWARE TERRACE 3 LIQUOR STORE LOUNGE OFFICE SECTION A - A 17 OFFICE TERRACE PLAY STATION BAR 16 4 PLAY STATION COUNTER BARBER SHOP 5 SHOP 15 FOOD KIOSK FOOD KIOSK 12 14 13 SALON 11 10 9 HARDWARE 8 FOOD KIOSK ELECTRICAL SHOP 7 HARDWARE 6 ( i ) USE OF ALTERNATIVE MATERIALS ON NEW EXTENSIONS, ( ii ) G.C.I. AS OPPOSED TO CLAY TILES. ( iii ) B/BOARD OR METAL SHEETS AS OPPOSED TO MASONRY. SCALE. FLOOR PLAN 0 3.5m 7m 14m TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) Fig.5.50, Transformations – “Mausoleum” 207 Fig.5.51, Ukweli Fabricators Fig.5.52, Buru Buru Centre (Mausoleum to the left) 208 Other Transformations Recently other shopping outlets have been built, some rising as high as 5 floors Figs.5.49, 5.53 and 5.54. Winds and Tents pubs located on one of the original shops caused the transformation of this shop. The 4m fire gap (public passage way) adjacent to these pubs has been annexed and converted to private use of the pubs Figs 5.55 and 5.57. In general the Buru Buru shopping area is now a bee-hive of activities with the advent of new shopping outlets like the Uchumi Supermarket and Tusker Mattresses. However the short coming of these informal transformations is that, there is insufficient car parking provision, making it difficult for motorised shoppers. Other outlets have also sprung up in the form of disused containers, which are now used as retail outlets Fig.5.56. Fig.5.53, Recent Developments Fig.5.54, Tusker Mattresses Supermarket (A shift from the original centre) Fig.5.55, Interior-Tents Pub Fig.5.56, Converted Disused Container (Annexed 4m Passage) (Coca Cola Outlet). 209 4.5M SERVICE ROAD SECTION A - A 4.0M WIDE PASSAGE 4.0M WIDE PASSAGE ELEVATION 01 ELEVATION 02 01 BUTCHERY WC 02 BUTCHERY BACK YARD WC WC WC 4.0M WIDE PASSAGE A A LAUNDRY FLOOR PLAN ORIGINAL CONSRUCTION ( 1975 ) TENTS PUB WINDS PUB SECTION A - A SECTION B - B BUTCHERY M ELEVATION 01 JIKO COUNTER DJ ELEVATION 02 WC COUNTER SEATING A SEATING SEATING LAUNDRY SEATING A B SEATING WINDS PUB B F WC TENTS PUB KITCH. WC 02 01 BUTCHERY WC FLOOR PLAN SCALE. TRANSFORMED CONSRUCTION ( 2004 ) 0 4.0 8.0 16.0 Fig.5.57, Tents and Winds Pubs (Annexed 4m Passage) 210 6. CONCLUSIONS Summary In this concluding chapter, I first address issues arising directly from urban process in Nairobi as covered by the four informal categories discussed in the main text. Broader urban issues arising from the phenomenon of informality are then subsequently addressed, and thereby bridging the particular and the general. The Urban Process in Nairobi This study has shown that although informality has always impacted on Nairobi’s urban process, it was limited to the city’s periphery during the colonial period. This scenario arose due to the strict enforcement of authoritarian legislation, which was however relaxed in the post-colonial period, and thereby enabling informality to infiltrate the city proper. It was also shown that the development control structures inherited at independence were designed to contain settlement; these structures were unable to cope with the demand for growth due to the increased influx of people into the city in the postcolonial period. To exacerbate the situation, the colonial legacy of commoditisation of space and the issuance of individual land titles, allowed individuals to engage in informal transformations within their individual lots. With regard to urban land, most land within and around Nairobi is either government or privately owned, a fact which has led to a system of clientelism and patronage. This system enables government operatives to subdivide and allocate government land at a fee for their own individual benefit. The allottees then build structures for renting, where they may reside in part of the structure, or altogether be absent. These structures are based on the 1920s 10ft by 12ft bachelor bed space module which has persisted to this day. This 10ft by 12ft module as was seen in chapter 4 also determines how overall space is commoditised. Unlike other cities, in Nairobi there are very few pure squatters; most residents in informal settlements are tenants or renters, who pay rent to structure owners. This urban process, although helpful to the poor is not sustainable, as it is based on selfish short term interests of government officials and other middlemen. A more 211 transparent urban process, based on a clear land use policy would contribute to the common good of all residents. It was also shown that survivalist informalities, although mobile/transient and not manifested by physical structures, still impacts on space use, as it utilises communication spines for its operations. Additional space for these activities has to be factored into circulation corridors, for harmony to prevail among the various interested parties. Informal practices, particularly those in the primary category can be a source of lucrative business, even if the risks are high as was shown for example, by Alecky Food Kiosk plus structure ownership in informal settlements. The lack of a clear land use/housing policy has not helped the city, as it has made it difficult to articulate any physical development agenda. For this reason among others, many middle income residents who are willing and able to pay for urban services and infrastructure are left with no option but to source for these services informally. In fact, Jamhuri II development discussed in chapter 4 and Buru Buru, discussed in chapter 5 are morphological transformations occurring by default, due to the lack of clear policies. These transformations are not without rules as is normally assumed. Transformations in Mumias South Corridor strictly adhered to the double storey typology, and constructions beyond two floors were forcibly demolished. To planners and architects, these transformations can be a source of useful practices in terms of minimum standards and densities. The above not withstanding, these individualised transformations are not cost effective, and in the long term, well co-ordinated collective strategies will produce more affordable and better designed settlements. Experiments can be carried out using various options; site and services, core housing, shell only etc. The informal urban process currently produces the largest additional housing stock in Nairobi, in addition to generating employment opportunities for many residents. From the late 1970s, neither the government nor the city council has developed any new housing or commercial outlets for the increasing population; it is the informal process that has filled this gap. This informal process has also made it possible to integrate different income groups in housing areas. In Buru Buru for example, many single roomed or one bedroom apartments resulting from transformations are let out to people from the low income 212 group. These people ordinarily would have been unable to live in this type of neighbourhood without informal transformations. This study has also shown that the strategies taken by players in “diverse informalities” are sensitive and in tandem with prevailing economic circumstances. In most cases these strategies are socio-economic and spatial as opposed to social or legal. Survivalist operators/hawkers, often position themselves strategically according to the human traffic dynamics, which is a similar strategy many kiosk operators make. However the use of road reserves for roadside enterprises remains unstructured and informal. This could be enhanced if minimal services were provided, for example; sanitation, water and power supply. The urban process in Nairobi also showed that players in the intermediate and affluent informal categories mostly engage in spatial transformations, and consequently live with the legal and social implications that arise due to these transformations. In this regard, many Nairobians are willing to tolerate higher densities particularly in ex-formal settlements like Buru Buru. The additional monetary income accruing from transformations compensates for the increased densities. More over, in a system where retirement benefits are not well structured, income from extensions/alterations becomes a source of livelihood during retirement for many middle income retirees. The urban process in Nairobi has shown that about 60% of the residents live in informal settlements. In addition many people across all social-economic strata participate in the informal urban process; to the extent it can be argued that less than 20% of the urban process is formal. There is therefore a need for creating an environment where the more than 80% of the urban process can increasingly be formalised. This presupposition is based on the fact that informality is not cheap, and occurs by default due to dysfunctional formal processes. It was also shown that informalities can evolve from one category to another (evolution of a kiosk, Fig.4.7). This evolutionary approach can be a very useful strategy in the urban process, particularly with regard to phased development in conditions of limited resources. The three dimensional upgrading approach in Huruma by Pamoja Trust, if used in a large scale can increase population densities two to three fold. These can then enable the infusion of infrastructure and social facilities in informal settlements, if upgrading is carried out in-situ. 213 The transformations of the “Mausoleum” enabled 20 small scale enterprises to join the Nairobi economy. These transformations also had a multiplier effect of generating several employment opportunities for young people. These transformations were carried out using alternative building materials e.g. corrugated iron sheets as opposed to clay tiles; block board instead of concrete bricks etc. It was also evident that even in residential transformations; there was the prevalence of the use of alternative building materials, for example; trussed roof structure as opposed to mass produced maxi span slabs. The use of alternative materials and the employment of local fundis is a response to the small scale nature of these constructions and to local technological know how. I also reiterate that although informal transformations have been dominant in Nairobi’s urban process, they generally impact negatively on the existing infrastructure. Illegal/informal connections to the sewage system, water and power supply, denies the authorities much needed revenue. The carrying capacity of the services are stretched to the limit, resulting in; sewer bursts, power surges and water shortages. From the study of Nairobi’s “Diverse Informalities”, I conclude that; for there to be a more responsive urban process:• The contribution of the informal sector should be recognised and brought on board. • Urban planning and design should be two-pronged; both from above and below. • More resources, both financial and human, should be made available for urban development, including a serious political commitment. The above conclusions arise directly from Nairobi’s urban process, what now follows are conclusions based on broader issues raised by “Diverse Informalities”, with regard to the phenomenon of informality. Re-conceptualising Informality Current tools for analysing the informal phenomenon are inadequate for interpreting the urban condition in most third world cities. There are dominant traits that simplify the phenomenon into false dichotomies and unnecessary polarities; formal vs. informal, land use values vs. exchange values the state vs. the poor etc. (Castillo, 2000). Earlier notions 214 of the phenomenon of informal urbanisation appear in the work of Turner and Abrams (Abrams, 1964; Turner, 1968), but the first time the term informal was used with regard to urban policy was with the International Labour Office (ILO) Employment Mission to Kenya in 1972. At that time, studies on informality started as an economic concept, which later transformed into social and spatial concepts (Vidrovitch, 1991). It should however be noted that some informal practices were already embedded in the precolonial social economy. Therefore the informal sector (informality) was not a new reality, but as a residential and professional social category, it was produced as soon as Western capitalism entered Africa. On the other hand, some Marxist researchers have seen “informal” as a bourgeois term that covers up class relations. After initially embracing the concept of informal vs. formal, a number of social scientists began arguing that the dichotomy was not really helpful at all; actual cases of informal economic activity proved to be closely tied to the formal economy; and this undermined, it was argued the usefulness of maintaining the dichotomy (e.g. Skar, 1985). Nustad in Hansen and Vaa, 2004 on the other hand asserted that labelling of some social phenomenon as “informal” received widespread popularity in the 1970s, after Keith Hart, 1973 coined the term “informal economy”, one of a few concepts which have originated in anthropology and then has been taken up by economists. The term “informal” was originally meant to draw attention to the limitations of a certain approach to understanding economic activities: the application of economic models that rested on understanding of economic activities as rational and thereby open to enumeration. The informal was coined as a term for acts and processes that escaped these models: all the activities that were not captured by the economists’ understanding of what economic activities entailed. Thus “informality” is not itself a characteristic of an activity; it only signifies that it has been left out by a definition that is “formal”. But as the history of this concept clearly demonstrates, in naming there lies a peril; “the informal” instead of denoting a flux of social practices, was instead encompassed by formal models as a residual category for everything that escaped the conceptual grid of administrators and academics. The concepts “formal” and “informal” are useful as long as one recognises that informal practices are both constituted by, and must be analysed in relationship to, formal practices (Nustad in Hansen and Vaa, 2004:46). 215 The “informal dimension” is seen as a peculiar character of African urban reality. It is the dimension that, according to Simone, 2002 new forms of social interaction are developing and consolidating. They demand to be interpreted with innovative conceptual tools in order to be able to re-think the models of urban development and institutional typologies necessary to ensure a sustainable future to African cities. The categorisation of the informal phenomenon into self-help, spontaneous, informal etc. continues to marginalise and exclude from mainstream urbanity a large percentage of the process producing third world urbanity. Concepts such as traditional or informal sector are dead-ends. African cultural processes and African problems of unemployment are neither traditional nor informal (Vidrovitch, 1991:74). I choose to call third world urbanity “diverse urbanisms” as opposed to informal urbanity, so as to discard the stigma of informality (informality has generally been regarded as undesirable). By so doing, I acknowledge that the informal process involves much more than the construction of dwellings. With regard to human settlements, empirical evidence in Nairobi shows three categories of informal settlements; squatting, illegal subdivisions and alteration/extensions. The boundaries between these categories are not clear cut, as they tend to merge into each other seamlessly. Informality in Nairobi is heterogeneous, and in attempting to understand this phenomenon better, I propose “diverse informalities” as a tool for this inquiry. “Diverse Informalities” is a way of re-conceptualising the complex nature of the phenomenon of informality, with an emphasis on the spatial dimension, as opposed to models guided by legal, economic, social or anthropological distinctions. The informal urban process in Nairobi is characterised by diversity across the socio-economic strata of society thereby creating “diverse informalities”. I grouped these informalities into four categories; survivalist, primary, intermediate and affluent. Table 4.1 in chapter four showed the salient features of each of the categories, and, it is hoped that this categorisation and analysis will help in the deconstruction of informal urbanisation. Merits and Demerits of Informality In informal urbanisation, we are faced with many issues relevant to planning today, from social equity and poverty mitigation, economic growth and development to urban management and social participation. On top of these, informal urbanisation remains in 216 many respects an unsustainable trajectory with regards to the environment. Informality is a condition with important spatial connotations for the episteme of architecture and planning, and for the improvement of urban policies. A large percentage of the residents of Nairobi are living informally due to the mismatch between provision and demand for urban goods and services. In this regard, Simone, 2002 posited that; The present is a time of great difficulty in urban Africa. The majority of urban residents are living with fewer resources, capacities and hopes. Their sense of space, time and possibility is being altered. It is a life of no thought for tomorrow and “we are between life and death” are common expressions in Addis Ababa (Simone, 2002:2). Regardless of these uncertainties, African urban actors continue to make something of their cities. They continue to use them as contexts in which to secure some, albeit, limited livelihood and access to the larger world. In trying to cope with the difficulties of everyday life, households engage in multiple income-generating activities instead of specialising in the development and growth of particular economic activities. At independence in 1963, Kenya’s new ruling elite opted for a policy of continuity rather than change. This policy allowed Nairobi to evolve into a self-help city in the 1960s, in defiance to government, resisting control and regulation. The continued use of the colonial model of governance gradually led to an informal political order. This political order is a system grounded in a reciprocal type of interdependence between leaders, courtiers and the populace. And is a system that works, however imperfectly (Chabal and Daloz, 1999). This informal political system, functions in the here and now, not for the sake of a hypothetical tomorrow. Its legitimacy rests with its immediate achievements, not with long term ambitions, and as Chabal and Daloz summed it; In Africa, it is expected that politics will lead to personal enrichment just as it is expected that wealth will have direct influence on political matters. Rich men are powerful. Powerful men are rich. Wealth and power are inextricably linked (Chabal and Daloz, 1999:52). 217 The inherited colonial urban structures encouraged many people to live a dual culture, with a strong connection to a rural homestead, a phenomenon Lonsdale, 2002 has referred to as “straddling”. The colonial legacy also had a strong anti-urban stance, where the town was seen as an evil place (Burja, 1975; Hake, 1977; Lonsdale in Burton, 2002).The urbanisation process in Nairobi is not being accompanied by adequate economic growth, thereby creating room for informal processes which enhance the urbanisation of poverty. In Nairobi however, these informal processes are not limited to the urban poor, but occur across all socio-economic levels of society. These processes make it possible for the poor to access some limited means of livelihood. The informal sector creates jobs for the urban poor, which the formal sector is unable to create. This sector is the engine behind the many physical/morphological transformations taking place in Nairobi, which may be driven by the desire to survive or for capital accumulation. The desire to survive leads to the creation of small Home Based Enterprises (HBEs), for self or family. The desire for capital accumulation leads to the creation of additional lettable space, which can generate rental income, where the owner may be resident or non-resident. In addition, informality has several negative attributes, for example the allocation of land through the chief, informal yet officially sanctioned, provides benefits to some officials and underpins a system of patronage (NISCC, 1997:3). Evidence shows that in the Nairobi situation, there are no squatters per se; rather there are illegal slum/landlords that collect rent from illegal tenants. This system does not provide adequate tenure, and makes absentee slum/landlords reluctant to reinvest in informal settlements, leaving the poor structures and infrastructure to further decay. The profits from informal settlements accrue largely to these absentee landlords, while the haphazard layouts prevent the introduction of services. The high densities in these settlements lead to overcrowding, seriously endangering the health of inhabitants who have poor access to health services. However, these settlements do provide cheap accommodation which the poor can afford, something which the formal sector, be it public or private, has been unable to achieve. Informal urban processes put extra pressure on existing infrastructural services by way of illegal connections, making them to further deteriorate. This extra pressure has so far, somehow been absorbed by the Nairobi system. This could be as a result of engineers’ 218 tendency of using a big safety factor in the initial design. If infrastructural services are legally provided in informal settlements, they carry a symbolic dimension, since they give security in the land tenure when legal land tenure is not yet acquired. The emphasis on infrastructure in upgrading projects quite often negates the primacy of aesthetics thereby impacting negatively on the urban fabric. From the early 1990s, neo-liberalism made the state retreat from providing urban services in addition to the liberalisation of trade, markets and financial systems. This retreat led to the privatisation of these services, yet many residents continue to pay the state statutory fees towards these same services. This lack of direct intervention has also encouraged many private developers to provide inadequate services in their developments. In Buru Buru for example, the omission in building adequate shopping facilities, facilitated the mushrooming of informal outlets for these services. In addition it created room for manipulation and clientelism in the allocation of commercial plots in the central commercial zone. These allocations have enabled privateers to build commercial high rise buildings in this zone Fig.6.1. The majority of these types of developments do not have lifts, making the upper floors uncomfortable for users. Fig.6.1, Commercial High Rise Developments 219 Creating a Different Urbanity In the colonial and the immediate post-colonial period, the main producer of urban space was the state (public sector). However, the main producer of urban space from the late 1970s increasingly became the private sector, particularly the informal sector when it comes to urban space production in Nairobi. The inherited legal frameworks for urban development were designed to contain settlement rather than deal with rapid growth. This framework could not cope with the rapid population growth that occurred in the postcolonial period, leading to rapid informal urbanisation, which created its own type of urbanity. This urbanity was basically dominated by mix-use activities and structures, a contradiction to the post war European modernist functional city, which had previously modelled Nairobi’s urbanity. The regime change from the colonial to the new African elite did not change colonial urban structures, and the new regime continued to use these structures in the changed circumstances. In this regard Rossi posits that “the moments of institutional change can not necessarily be related to the evolution of urban form” (Rossi, 1982). For example Haghia Sofia in Istanbul has served as a mosque, or a cathedral depending on who was in power, either Muslims or Christians. Therefore on the attainment of independence, Nairobi’s urban form and for that matter its production and consumption of urban space remained basically colonial. However, the urban realities of; poverty, unemployment, mismanagement, corruption etc. have made it possible for a different type of urbanity to evolve in Nairobi. It is evident that, urbanisation in most third world cities (Nairobi included) was guided by the prevailing global development paradigms illustrated in Table 6.1. All these paradigms did not produce the desired urbanity and economic growth, and Nairobi continued to develop informally. Because of this failure, in the 1980s, there was a relaxation of the inherited rigid development control measures. This gave rise to upgrading projects, whose emphasis was on settlement regularisation. However, regularisation is not entirely neutral, it is closely tied to political patronage, and consensus building and party favours (Castillo, 2000).Regularisation, makes settlers dependent on political favours, where urbanity is granted through political negotiation. This urbanisation by decree, forces residents to invest more in political actions and lobbying than in productive activities that 220 would improve their economic and social conditions. Regularisation policies are also problematic, as they focus primarily on the issue of tenure, rather than on a broader conception of the urbanisation logic. The assumption that only through legal transformations, the informal segment of the city would be incorporated, ignored that regularisation is just a minor step incorporating informal settlements to the city. Evidence shows that in Africa, human relationships are more important than legal procedures. On this basis, Jenkins posits that, the emphasis on legality and economics as the main variables in urban processes should be minimised and social, cultural and political variables enhanced. He further argues that “in reality, levels of legality range from full illegality through complex matrices to levels of legality” (Jenkins in Hansen and Vaa, 2004:211). Table 4. Global Development Paradigms and their Characteristics Time Dominant Geopolitical Strategy for Period Orthodoxy Trends Urbanisation 1960s Modernisation Emergence of Import substitution Theory with a newly independent strategy for strong Western countries and the industrialisation. bias cold war Slum eradication Growth and Cold war, Focus on site and Redistribution Oil shock and the service schemes, Theory. Emergence of self-help projects, Basic Needs Debt crisis core housing etc. 1970s Theory. Projects to satisfy: Affordability-Cost Recovery and Replicability 221 1980s Emergence of the Debt crisis Full - Problems of affo- Neo-liberal Theory blown. rdability came to Severe economic fore. decline of develo- Tacit acceptance ping countries of informal settlements. Relaxation of laws. 1990s Neo-liberal Theory End of cold war. Cities increasingly the driving orthod- Increased empha- seen as engines oxy. sis on democrati- of economic growth. Emphasis on sation based on Restrictive building Enablement and Western models. and land-use sta- Good governance ndards increasingly being phased out. 2000s Sustainable Liveli- USA as the Privatisation. hoods Theory. dominant super Focus on private/ Focus on poverty power. publis sector eradication Increasing urban partnerships poverty. Source: Authors Reconstruction from Syagga, 2002 This emphasis on legality could be having its roots in the history of local authorities. In the 1930s the “amateur” period of civic management had come to an end, and civic authorities had to lean on professionals. The town clerk (a lawyer), became the chief executive of the local authority during this period of professionalizing civic management. This could be one reason why many urban issues are addressed through legal lenses. This colonial legacy has not helped in the complex post-colonial urban condition, since the variables at play quite often are beyond legalities. May be what urban areas require is to have a chief executive who is competent in planning and urban management. 222 Regularisation suffers another problem, the operational legal regime is that inherited from the colonial period and has little changed in the post-colonial period. For example, the British Town and Country Planning Act of 1932, is the source of planning law in Kenya and other ex-colonies. The Public Health Act is another neo-colonial Act that has a bearing on urbanity, as the use of the grid iron layout pattern enhanced the enforcement of the Public Health Act. The grid iron pattern also enabled the ease of surveillance and domination (Myers, 2003). It can also be argued that tenure regularisation without physical planning doesn’t work. This is because regularisation involves legal procedures which may have little bearing on spatial configurations. For tenure regularisation to work, it must go hand in hand with physical planning, where spatial policies are also addressed. The notion that legal land title will prompt settlers to improve and upgrade their dwellings does not necessarily work. Settlers in addition to legal land titles, also require technical support in the form of design typologies, access to affordable finance and state support in the provision of infrastructural services (collective consumption goods). New urban forms are also resulting from the inadequacy of current legislation. The bylaw requiring spatial configurations of settlements to have building set backs along roads is a case in point. In Buru Buru for example, set backs of 6-9m were allowed on access and distributor roads. These set backs as discussed in chapter five, have over the years undergone major transformations, with many people building up to the plot boundaries in defiance of the by-law. The emerging different urbanity, where there is scarcity of affordable serviced land cannot afford the luxury of 6-9m building set backs. In this urbanity, people are addressing the realities of Nairobi’s socio-economic and political conditions. In this urbanity, people are willing to compromise on environmental quality by tolerating higher densities, as long as there are monetary gains accruing from these higher densities. Security is another variable shaping this new urbanity; many pedestrian passageways have been closed both in Nairobi’s CBD and residential areas. In Buru Buru, many courtyards now have only one entry/exit point manned by askaris, and fitted with metal grille gates or turn pikes, creating a sort of gated community. Generally new hybrid urbanity is emerging, where the dominant building type is a double storey development. The observance of this double storey construction seems to be an agreed silent rule 223 among the settlers; developments beyond two stories are vehemently resisted through demolitions. The transformations in Buru Buru show that; transformations can be used as an urbanisation strategy, where settlements are designed for transformations to occur over time. This will entail the development (design) of various building typologies that can be extended or modified, such that a coherent whole can be achieved during the consolidation period. This strategy will make better use of resources by maximising on the investment potential, and minimising conflicts among settlers. Diverse informalities have shown that the deficiency in urban structures, make people create alternative strategies for survival. No system can be entirely perfect, however for sustainable urban development to occur; urban structures should enable residents to pursue their individual livelihoods. Urban Integration Commissioner Charles Eliot, in 1900 believed that with European settlement, the Kenya colony would be profitable in ten years, based upon a policy of integrated and not separate development (Hirst, 1994). This vision was however swiftly changed, and separate development established as policy on the advent of the first European settlers. This was the beginning of social, economic and political exclusion of Africans in matters affecting the colony. At that time, all Africans who were not in European employment were building subsistence urbanisation through independent informal sector development, without the benefit of Town Planning, and thereby creating the beginnings of informality. Although these subsistence settlements provided jobs for many Africans, Nairobi’s European citizenry had long viewed these settlements as havens of disease and criminality, and advocated for their demolitions. In addition to the above conditions, from the beginning, Nairobi was designed around personalised transport; starting with horses, bicycles then rickshaws and finally the motor car ruled (Hirst, 1994; Nevanlinna, 1996). These colonial conditions were good ground for the propagation of a segregated city. Urban integration could only occur if all the socio-economic and political structures were overhauled. 224 At independence, Nairobi inherited a multicultural society in which privileges had been unevenly divided; the density distribution was uneven based on race and social status, education and healthcare were similarly segregated. The most striking aspect of colonial urbanisation was the logic of partitioning urban space into two zones. The “European zone” and the “Indigenous zone”, in the case of Nairobi, there was a third “Asian zone”, making the colonial city heterogeneous and segregated. According to Home, 1983, the physical separation of colonial from traditional urban forms created “twin cities” in symbiotic relationship. These twin cities in turn created parallel governance structures; “Native” and “European” based on the colonial logic of indirect rule (Myers, 2003). After 50 years of colonial rule, there was a chance to create a new colonial city, when a multidisciplinary team of South African consultants was commissioned to make an urban development proposal for Nairobi. The 1948 Master Plan which was prepared by these consultants proposed the neighbourhood as the basic planning unit. Nairobi was subsequently divided into 50 neighbourhood units, each unit surrounded by a distributor road (Thornton White et al. 1948). Although the proposals advocated for humanism and neutrality on the subject of racial segregation, political and educational action continued to advocate for segregation, and further minimised the chance for integrated urban development. In recent times however, many urban residents seem to be keen on living in situations similar to the 1948 neighbourhood unit proposal. Urban research has shown that many slum areas in developing countries as well as inner cities of the developed world, between 50-70% of all dwellings double as workshops and family-based crafts and production of goods or as shops of small-scale traders. These are not just providing housing facilities that require improvements, but are the anchoring point of a local economy that supplies the inhabitants of the settlements with a vital source of income. This view was supported at a workshop of slum residents held on 11th April, 2001 in Nairobi at which they expressed the need for workplaces in their neighbourhoods, since the majority of them had no formal employment (Syagga, 2002:6). This expressed need is pointing towards a solution akin to the Thornton White et al. 1948 proposal, which advocated for neighbourhood units, with each unit being self-sufficient 225 with its own work places. The 1948 Master Plan also seems to have had an influence in the planning of Buru Buru, as the central communal space for social amenities is similar to the neighbourhood unit proposal. Master Planning as a development control tool has not been used for purposes of urban integration. In Nairobi like elsewhere, it has been used as a political tool to maintain the status quo, where the small ruling elite continue to benefit from the uneven distribution of resources. The 1973 MGS was a tool for state intervention which further enhanced segregated development. It supported the interests of the hegemonic class alliance of the local bourgeoisie and the MNCs. The interests of the urban majority were neglected in a similar way as was done by the three preceding colonial plans. Segregation was now based on economic and class lines as opposed to the racial and class lines previously used. The use of functionalism in the MGS, as an expression of universal human values as perceived by the MNCs, was a technical justification for continued segregation. There are many variables that can be used for urban integration, urban transport is one variable among others. In Nairobi however, this has never been addressed, from the early days of personalised private transport, public transport is still privatised even today. The dominant matatu mode of transport does not work for the common good, and a concerted effort must be made to create a viable public transport system that can support urban integration. Nairobi’s demographic data shows that more than one million people who live in informal settlements are marginalised. They benefit little from urban services yet they contribute to the city economy, even if insignificantly, their plight needs to be addressed if any meaningful integration has to take place. This could be achieved by creating a public transport system that is all inclusive. On the other hand, Nairobi’s full potential as a viable economic, industrial and political hub in East Africa can only be achieved if policies of integration are adopted. From a legal perspective, the illegal city should be accommodated within the legal city if reality on the ground is to be reflected in law, because the credibility of the law will be seriously undermined if the majority of the citizens are classed as illegal (Mitullah and Kibwana in Fernandes and Varley, 1998:191) The inquiry into urban space has dealt with the issue of urban integration, and has identified the shortcomings of regularisation which has interpreted integration in a 226 shallow way; as a legal and fiscal category. Castells’ argument (Castells, 1983) on the idea of citizenship is a good starting point in considering what integration should mean. For Castells, the idea of citizenship should mean, belonging to a city. In this study I consider integration to mean, the possibility of having equal opportunity to jobs, transportation, leisure, health and educational services. This position has also been taken by Castillo in his study in 2000, who further observed that; The success of any urban policy will depend on the ability to recognise integration as the mechanism for people to overcome their conditions of poverty (Castillo, 2000:147). Diverse Informalities as a tool for understanding the urbanisation process in Nairobi has been based on the assumption that the lessons learnt from informal urbanisation can help improve the city. Empirical evidence shows that diverse informalities have generated some creative solutions to the problems of urbanity in circumstances of limited resources. The spatial framework adopted for diverse informalities rather than legal or sociological lenses, allows designers (planners/architects) to address urban issues in a more comprehensive way by establishing a continuum, from policy to plan to project. Policies of informal urbanisation should concentrate on preserving scarce resources and minimising adverse impacts of development. A critique of Regularisation Policies The regularisation policy has remained functional for some time, although it has the potential of creating large areas that while legal, will remain sub-urbanised. Settlements where most residents have acquired legal title to land and fiscally integrated may have the same developmental deficiencies as places without the legal title. This brings into focus the need for a holistic approach to city making as opposed to regularisation which in effect is urbanisation by decree. The dominant arguments against regularisation are that regularisation will foster continuous informal urbanisation, and secondly, it is based on the fear that by incorporating informal areas into the formal regime, the poorer settlers will be further pushed out into the fringe to start the informal cycle all over again. Although regularisation and the cost recovery money paid by settlers to obtain services and infrastructure serve an important purpose, regularisation is flawed in many respects. 227 Firstly, it does not address the needs of the poor to help them overcome poverty, and is considered as a “handout” to the poor, which far from serving their interests, ultimately limits their ability to change. Secondly, regularisation remains a reactive policy without any strategic role in defining goals, policies or scenarios. It is more concerned with damage control than with actual transformation of the urbanisation process. Thirdly, by focusing on the issue of land tenure, regularisation ignores the most important aspects of development, which should facilitate access to jobs, services and opportunities. The fact that regularisation has become such a strong policy represents a decision by the state to choose this modality of planning and social policy over others, such as facilitating people’s access to serviced land or housing by providing land reserves. This choice in policy has been informed by the political benefits of regularisation. As opposed to other modalities of planning, regularisation has a “high-impact” political effect. It allows the state to keep the poor faithful to the system and to selectively and centrally administer social welfare. It additionally minimises the conflict among stakeholders by eliminating the notion of fraud, wrongdoing and conflict. The regularisation process appears as a conciliatory gesture rather than an application of the law (Azuela, 1989 in Castillo, 2000:93). Informal processes happen with the full knowledge of the state; from the government’s tolerance of illegal sales and subdivisions, to the painless regularisation process, the authorities recognise that informal developers fill in a social void. Not only is urban law negotiated among stakeholders, but even worse, urbanity is granted by “decree”. This is probably one of the most unfortunate costs of informal urbanisation for settlers and society. Residents are forced to invest more in political actions and lobbying than in productive activities that would improve their economic and social conditions (Castillo, 2000:38) The Role of Design in Settlements What is the role of design in contemporary urban processes? The current circumstances in most third world cities demand that design mediates between various actors in the urbanisation process i.e. public sector, private sector and individuals. The complexity of contemporary society, particularly in a context of informality requires the services of a 228 professional who can priotise and articulate the competing needs of settlement requirements. In recent times, the role of design has increasingly become marginalised in informal urbanisation, while social scientists have played a much bigger role in this process. It is indeed time for design to once again take its rightful position in this process. In Nairobi today, almost 60% of the population lives in informal settlements, these settlements which form part of the urban space are produced informally. If designers (architects and planners) are keen on discussing urban space, how can they ignore this large proportion of the city that is creating urban space? In many third world cities, poor people normally act by example, which creates an opportunity for design intervention, by way of developing solutions that go beyond the functional requirements of the urban poor. These solutions should take cognisance of the social, economic, political and cultural dynamics of the city. From a historical perspective, Ildefons Cerda`, 1855, in Barcelona attempted to deal with the issue of prototype. He developed two types of urban blocks (minimum urbs), for the middle class and the workers Fig. 6.2. He went further and proposed a grid system incorporating circulation networks that were required to support these blocks. Contemporary design in third world cities needs to adopt this kind of holistic approach. Cerda`s minimum urb eventually became the European “urban prototype”. This block was basically an amalgam of several lots that created a block with possibilities of having frontages on all four sides. It offered each individual lot in the amalgam street frontage, making the block fairly democratic. Contrary to this, the colonial urban block developed for Nairobi was an individual lot measuring 50´x100´ (15mx30m) for commercial lots and about 6mx20m for middle income residential lots. This typology affords the lot a street frontage on only one side, unless it is a corner lot. In the Buru Buru courtyard layout, where courtyards can be back to back, some lots end up having no street frontage Fig.6.3. The lack of a street front in some lots in the Buru Buru typology deprives these lots the possibility of engaging in commercial activities, which are more viable on street fronts. To some extent, the Buru Buru layout also creates a fire risk as it has limited exit routes; it also presents servicing problems for services that may run at the back of lots. 229 Fig.6.2, Cerda`s Minimum Urb The European block was built up to the plot boundary, which made it possible to articulate the urban edge. Over the years transformations have taken place in the courtyard space, originally designed as an internal garden, but the urban edge has remained pretty much the same in the last 130 years. There was no possibility of defining the urban edge in Buru Buru, because of the 6-9m building set back, which only created room for later day ad-hoc transformations. The proliferation of transformations on built forms and open spaces is due to the fact that these spatial configurations are inadequate in satisfying people’s needs. According to De Soto, 2001 in order to satisfy people’s needs, extralegal transformations evolve over time until they are barely distinguishable from property that is perfectly legal. This process seems to have some merit, and is the responsibility of designers to anticipate these dynamics by creating the necessary frameworks that will enable these transformations to occur. 230 Fig.6.3, Typical Buru Buru Courtyard Layout Fig.6.4 illustrates how design intervention could have anticipated the transformation process. In this regard, De Soto argues that; By bringing the extralegal sector inside the law, an opportunity will be opened up for massive low-cost housing programmes that will provide the poor homes that are not only better built but much cheaper than what they themselves have been building in the extralegal sector (De Soto, 2001:205). The study model in chapter two also showed that the majority of the population in third world cities operate in the informal sector. This reality by itself presents an opportunity for professional design intervention. Turner in Burgess et al, 1997 argues that the role of the architect/planner is to mediate between global sustainable development and participatory development at neighbourhood level, while allowing grater autonomy to communities. On the other hand Rossi, 1982 recognised the work of Carlo Aymonino, who envisaged the end of zoning. The end of the system of horizontal usage (zoning provisions), and by the usage with purely volumetric-quantitative building utilisation. The architectural section 231 then became one of the governing images; the generating nucleus of the entire composition (Rossi, 1982:118). Aymonino’s concept actually envisaged the death of naïve functionalism; zoning, form/function relationship. I agree with this concept and further emphasise that in mediating between various urban actors, the role of design will be to negotiate with the various actors and create this relevant architectural section. Fig.6.4, Sections - Professional Intervention The role of visual attributes in design and therefore city making can not be overlooked. Visual attributes play a major role in constituting identities, as the city according to Rossi, 1982, is composed of monuments and artefacts which are mostly a visual phenomenon. This visual phenomenon requires articulation through design. In Nairobi, most upgrading projects put emphasis on regularisation and infrastructural services, and more or less disregard the design of the dwelling units, resulting in a nondescript urban fabric. Empirical evidence has shown that local artisans use alternative materials in building the extensions in the study corridor. For example they consistently use A-frame timber truss 232 system, the question is why do they do so? This may be because local fundis have no exposure to other technologies and construction systems. In the Buru Buru case, the original roofing was made of clay tiles laid on hollow pot maxi span slabs. This technology works efficiently when applied through mass production, and is therefore not appropriate to individual transformers who operate at their own pace. It was noticed also that rather than use clay tiles they prefer concrete tiles, which are easier to lay. This is a situation where design intervention, can facilitate technology transfer and in the process create enhanced built forms Fig.6.5. The building type, currently being generated in the study corridor is creating a potential dangerous wind tunnel. It has also reduced the privacy and visual comfort of the original buildings this could have been avoided through design. The transformations in the study corridor are re-defining the urban edge by reframing the relationship between the container and the contained, the inside and the outside, which contravene the colonial logic of spatial order. They in effect are creating a more urban prototype and thereby urbanising the original suburban prototype. In this case the transformers are taking the lead in defining appropriate laws on the ground, which the city authorities should consider for incorporation in the formal statutes. The American pre-emptive law of 1830 is a good example of how to formalise informal practices (De Soto, 2001). From the foregoing, it is evident that although informality is practiced across all social categories of Nairobi’s residents, the three main categories would require different spatial design interventions Fig.6.6. For low income settlements, allowance should be made to accommodate Home Based Enterprises, while high income settlements do not require provision for HBEs. Alexander’s Peru competition proposal, where he developed the “Generic House” (Houses generated by patterns, 1969) is a case in point. 233 Fig.6.5, Sections - Design Options 234 Fig.6.6, Layout and Sections-Design Options (For Various Income Groups) 235 8. APPENDICES Appendix 1: Nairobi City Area – Case Study Locations 248 Appendix 2: Other Images of Nairobi Railway Station 1901 Kibera, Laini-Saba Railway Station 2005 Un-grassed Open Ground Middle Income Gated Housing - Kilimani 249 Nairobi CBD Skyline Nairobi’s Glass Towers Yaya Centre – Shopping Mall 250 7. BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbott, J. 2002: An analysis of informal settlement upgrading and critique of existing methodological approaches. Habitat International 26, 2002:303-315. Abbott, J. 2002b: A method based planning framework for informal settlement upgrading. Habitat International 26, 2002: 317-333. Abrams, C. 1964: Man’s struggle for shelter in an urbanising world. MIT Press, Cambridge. Abrams, C. 1966: Squatter settlements: the problem and the opportunity. In ideas and Methods Exchange No.63. Washington D.C.: Office of International affairs, Department of Housing and Urban Development. Albertsen, N. and Diken, B. 2004: Welfare and the city. Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2004, 2: 7-109. Alexander, C. et al. 1969: Houses generated by patterns. Centre for Environmental Structure. Berkeley- California. Alexander, C. et al. 1977: A pattern language; Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford University Press, New York. Angel, S. (Ed), 1983: Land for housing the poor. Select books, Singapore Amin, S. 1976: Unequal Development. Monthly Review Press, New York. Amis, P. 1996: Long-run trends in Nairobi’s informal housing markets. Third World Planning Review. Vol. 18, No.3: 271-285 Ayittey, G. B. N. 1993: Africa Betrayed. St. Martins Press, New York ABCD Workshop, 2000: Report on the workshop held in April 2000 in Durban-South Africa, Theme- “The African CBD” Bandini, M. 1997: The conditions of Criticism, Architecture Education. Post Renaissance Post Modern, M. Pollok (Ed), The MIT Press Bell, J. 1993: Doing your research project. Open University Press, Milton Keynes Berman, B. 1990: Control and crisis in colonial Kenya: the dialectic of domination. James Currey, London. Burja, J. M. 1975: Women “Entrepreneurs” of Early Nairobi. Canadian Journal of African Studies. Vol.9, No.2 (1975): 213-234 236 Burgess, R. et al. 1997: The challenge of sustainable cities; Neo-liberalism and urban Strategies in developing countries. Zed Books, London, New York. Burton, A. (Ed), 2002: The urban Experience in Eastern Africa c.1750-2000. Azania Special volume xxxvi-xxxvii. The British Institute in Eastern Africa. Callinicos, A. 2004: The revolutionary ideas of Karl Marx. Bookmarks Publications London and Sydney. Caminos, H. et al. 1969: Urban dwelling environments. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Caminos, H. and Geothert, R. 1978: Urbanization Primer. MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, London. CARDO, 1993: Transformations of Government Built Low Cost Housing as Generators of Shelter and Employment. A Reader, University of Newcastle on Tyne. Castells, M. 1978: City Class and Power. Translation supervised by Elizabeth Lebas Macmillan, London Castells, M. 1983: The city and the grassroots: a cross-cultural theory of urban social movements. Edward Arnold, London Castex, J. 1979: Space as representation and space as practice, a reading of the city of Varsailles, In Lotus International, 24:85-94. Castillo, J. M. 2000: Urbanisms of the Informal; Spatial Transformations in the urban fringe of Mexico City. Doctoral Thesis, Harvard Design School. UMI Dissertation Services, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Chabal, P. and Daloz, J-P. 1999: Africa Works; Disorder as Political Instrument. James Currey, London. Chana, T. S. and Mbogua, J. P. 1996: Sector Review on Capacity Building for Metropolitan Governance of Nairobi. United Nations Development Programme, Nairobi. Chen, S. et al. 1999: Counting the invisible work force; the case of home-based workers. World Development, 27, 3: 603-610. Cissoko, S. M. 2002: The African City: a source of progress and modernity. African studies, e-magazine No.3, 2002. City Council of Nairobi, 2004: Draft Strategic Plan 2004-2009. Nairobi. 237 Cohen, G. and Atieno-Odhiambo, E. S. 1992: Burying SM: The politics of knowledge and the sociology of power in Africa. Heinemann, Portsmouth. Connah, G. (Ed). 1998: Transformations in Africa; Essays on Africa’s later past. Leicester University Press, London, Washington. Cooper, F. 1987: On the African waterfront: urban disorder and the transformation of work in colonial Mombasa. Yale University Press, New Haven. Cornelius, W. and Trueblood, F. 1975: Latin American Urban Research 5. Sage Publications, Beverly Hill/London Correa, C. 1985: The new landscape. The book society of India, Bombay Darin, M. 1998: The study of urban form in France. ISUF Urban Morphology 1998, Vol.2 No, 2: 63-76. Davidson, B. 1978: Africa in Modern History. Penguin, London De Soto, H. 2001: The Mystery of Capital: - Why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. Black Swan, London Dierwechter, Y. 2002: Six cities of the informal sector and beyond. International Development Planning Review, IDPR, 24 (1) 2002. Dinesh, M. 2000: Urbanisation of poverty, UNCHS (Habitat), Habitat Debate, Global Overview, 2000- Vol.6, No.4. Doebele, W. 1987: Land Policy, in Shelter, settlement and development, Ed. Lloyd Rodwin. Allen and Unwin, Boston Emig, S. and Ismail, Z. 1980: Notes on the urban planning of Nairobi. Royal Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture, Copenhagen. Engels, F. 1993: The conditions of the working class in England (McLellan, D. (ed.) Oxford University Press, Oxford. Environment and Urbanisation Brief-9 (2004): Reshaping local democracy through Participatory governance. Environment and Urbanisation, Vol.16, No.1. Etherton, D. 1971: Mathare Valley; a case study of uncontrolled settlement in Nairobi. HRDU, University of Nairobi, Nairobi Farmer, B. Louw, H. 1993: Companion to contemporary architectural thought. Routledge, London, New York. Fernandes, E. and Varley, A. (Eds). 1998: Illegal Cities; Law and Urban Change in 238 Developing Countries. Zed Books, London, New York. Freeman, D. B. 1991: A city of farmers: Informal Urban Agriculture in open spaces of Nairobi, Kenya. McGill University Press, Montreal and Kingston Friedman, D. 1988: Florentine New Towns (Urban Design in the Middle Ages) The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, London. Friedman, J. 1986: The World City Hypothesis, Development and Change, Sage Publication, London, Beverly Hills and New Delhi. Vol.17: 69-83. Frisby, D. (Ed), 1994: Georg Simmel: Critical assessments. Routledge, London Galtung, J. 1988: Methodology and Development; Essays in Methodology, Volume Three. Christian Ejlers, Copenhagen. Gibbons, M. et al. 1994: The new production of Knowledge, Sage, London. Gilbert, A. and Varley, A. 1991:Landlord and Tenant: housing the poor in urban Mexico. Routledge, London, New York Gilbert, A. and Ward, P. 1985: Housing, the state and the poor: policy and practice in three Latin American cities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. 1967: The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Observations. Gordon, A. 1974: The long life/loose fit/low energy study; Architects and resource conservation. RIBA Journal, January 1974. Government of Catalonia, 2001: Cerda`-The Barcelona extension (Eixample). Magazine for the travelling exhibition: “Ildefons Cerda`, the visionary urban planner. Government of Kenya, 1983: Laws of Kenya; the land acquisition act, chapter 295. Government Printer, Nairobi. Government of Kenya, 1970: Laws of Kenya; the land planning act, chapter 303. Government Printer, Nairobi. Government of Kenya, 1989: Laws of Kenya; the land control act, chapter 302. Government Printer, Nairobi. Graham, S. and Marvin, S. 2001: Splintering Urbanism; Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition. Routledge; London, New York. Greenfield, K. 1995: Self and Nation in Kenya; Charles Mangua’s Son of Woman. 239 Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol.33, No.4: 685-698. Gutkind, P. C. W. 1969: Tradition, Migration, Urbanisation; Modernity and Unemployment in Africa: The roots of instability. Canadian Journal of African Studies, Vol.3, No.2, Special Issue: Unemployment in Africa (Summer 1969): 343-365. Gutkind, P. 1960: Notes on the Kibuga of Buganda, Uganda Journal, 1960 (1): 29-40. Hake, A. 1977: African Metropolis; Nairobi’s Self-help City. Sussex University Press, London. Hall, P. and Ward, C. 1998: Sociable Cities: the legacy of Ebenezer Howard. Wiley, Chichester. Hannerz, U. 1996: Transnational connections: Culture, People, Places. Routledge, London. Hansen, K. T. and Vaa, M. (Eds). 2004: Reconsidering Informality; Perspectives from Urban Africa. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Upsalla. Harden, B. 1990: Africa; Dispatches from a fragile continent. Harper Collins Publishers, London, New York. Harris, J. 2001: Depoliticizing Development; the World Band and Social Capital. Leftword, New Delhi. Harris, R. 2003: A double irony: the originality and influence of John F. C. Turner. Habitat International 27 (2003): 245-269. Harris, R. 2003: Learning from the past: International housing policy since 1945- an Introduction, Habitat International 27(2003): 163-166. Harris, R. and Giles, C. 2003: A mixed message: the agents and forms of international Housing policy, 1945-1973. Habitat International 27(2003): 167-191. Harvey, D. 1986: Consciousness and the urban experience; studies in the history and theory of capitalist urbanization. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland. Harvey, D. 2000: Spaces of Hope. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh. Hirst, T. assisted by Lamba, D. The struggle for Nairobi; A documentary comic book. Mazingira Institute, Nairobi. Home, R. K. 1983: Town planning, segregation and indirect rule in colonial Nigeria. 240 Third World Planning Review, Vol.5, No.2: 165-176. Home, R. K. 1997: Of planting and planning; the making of British colonial cities. Spon, London. Hooper, C. 1975: Design for Climate: Guidelines for the design of low cost houses for the climates of Kenya. HRDU, University of Nairobi, Nairobi House, W. J. 1984: Nairobi’s informal sector: dynamic entrepreneurs or surplus labour? In Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol.32. No.2 (Jan, 1984): 277302 House, W. J. Ikiara, G. K. and McCormick, D. 1993: Urban self-employment in Kenya: Panacea or viable strategy? World Development 21: 1205-1223 Housing and Land Rights Committee, 2001: Report of Habitat International Coalition (HIC), Fact Finding Mission to Kenya on the right to adequate housing. Nairobi. Jenks, C. 1987: Le Corbusier and the tragic view of architecture. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth Jenks, M. and Burgess, R. (Eds.). 2000: Compact Cities; sustainable urban forms for developing countries. Spon Press, London, New York. Kabagambe, D. and Moughtin, C. 1983: Housing the poor; A case study of Nairobi. Third World Planning Review, Vol.5, No.3: 227-248 Karuga, J. G. (Ed). 1993: Action towards a better Nairobi; report and recommendations of the Nairobi city convention “the Nairobi we want”. City Hall July 27-29, 1993. King, A. D. 1976: Colonial Urban Development; culture, social power and environment. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London Krier, R. 1979: Urban Space, Academy Editions, London. Krier, R. et al. 2003: Town Spaces, Birkhauser, Basel. Lado, C. 1990: Informal urban agriculture in Nairobi, Kenya: problem or resource in Development and land use planning? Land use policy 7: 257-266 La Ferrara, E. 2002: Self-help groups and income generation in the informal settlements of Nairobi. Journal of African Economies, Vol.11, No.1:61-89. Lamba, D. 1994: Nairobi Action Plan: City Environment and Sustainable Development. Mazingira Institute, Nairobi. Lamba, D. 1994: Nairobi’s Environment; A review of conditions and issues. Mazingira 241 Institute, Nairobi. Landau, R. 1985: The culture of architecture; a historiography of the current discourse. International Architect, No.5/1985. Lasserve, D. 1987: Land and Housing in Third World Cities: Are public and private Strategies contradictory? Cities-November 1987, Butterworth and co. ltd. Lasserve, D. A. 1998: Law and urban change in developing countries: trends and issues In “Illegal cities: law and urban change in developing countries (Ed) Fernandes, E and Varley, A. Zed Books, London, New York Lee-Smith, D. 1997: My House is my Husband; A Kenyan study on women’s access to Land and housing. Doctoral thesis, Lund University, Sweden. Lee-Smith, D. and Lamba, D. 1998: Good governance and urban development in Nairobi. Mazingira Institute, Nairobi. Lee-Smith, D. and Stren, R. 1991: New perspectives on African urban management. Environment and Urbanization 3: 23-36 Lefebre, H. 1979: Space: Social product and use Value. Translated by Freiberg, J. W. in Critical sociology; European perspectives (285-295), Irvington Publishers. Lubell, H. 1991: The informal sector in the 1980s and 1990s. Development Centre Studies. Washington D.C. OECD Publications Lupala, J. M. 2002: Urban types in rapidly urbanizing cities; analysis of formal and informal settlements in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Doctoral Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. Mabogunje, A. 1994: Urban land and urban management: policies in Sub-Saharan Africa. In urban perspectives, Vol.4, No.2, Feb. 1994. McAuslan, P. 1994: Land in the city: the role of law in facilitating access to land by the urban poor. Background paper for the 1996 Global Report on Human Settlements Macharia, K. 1992: Slum clearance and the informal economy in Nairobi. Journal of Modern African Studies 30: 221-236 Manuel, C. 1978: City, Class and Power. Translated by Elizabeth Lebas. St. Martins Press, New York. Massey, D. 1994: Space, Place and Gender. Polity Press, Cambridge. 242 Matrix Development Consultants, 1993: An overview of informal settlements in Nairobi. An inventory. USAID: Office of Housing and Development Programmes Mitchell, T. 1991: Colonising Egypt. University of California Press, BerkeleyLos Angeles, Oxford. Mitchell, W. J. T. 1994: Picture theory; Essays on verbal and visual representation. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Mitlin, D. et al. 1996: City Inequality. Environment and Urbanisation, Vol. 8, No.2. Moore, K. D. (Ed). 2000: Culture-Meaning-Architecture; critical reflections on the work of Amos Rapoport. Ashgate, Aldershot. Burlington-USA, Singapore, Sydney. Moudon, A. V. 1997: Urban morphology as an emerging interdisciplinary field. ISUF Urban morphology 1997, 1: 3-10 Morgan, W. T. W. 1967: Nairobi: City and Region. Oxford University Press, Nairobi, London, New York. Mulenga, C. et al. 2004: Upgrading of urban informal settlements; Evaluation and Review of upgrading and poverty reduction activities in three settlements in Lusaka, Zambia. Norwegian Building Research Institute, Oslo. Mwangi, I. K. 1997: The nature of rental housing in Kenya. Environment and Urbanisation. Vol.9, No.2: 141-159. Mwaniki, B. W. 1985: Housing production in Nairobi: some policy issues-working Paper, Research Section, City Planning and Architecture Department, City of Nairobi. Myers, G. A. 2003: Verandas of Power; Colonialism and Space in Urban Africa. Syracuse University Press, New York. Myers, G. A. 2003: Defining Power; forms and purposes of colonial model Neighbourhoods in British Africa. Habitat International, 27(2003): 193-204. Nairobi Urban Study Group, 1973: Metropolitan Growth Strategy. Report on the development of Nairobi up to 2000. Nairobi Nalo, D. S. O. 2002: Report of the CBS/UN-Habitat on the delineation of the urban Slums/informal settlements and the 1999 census; a case study of Nairobi. Nairobi. Nesbitt, K. (Ed). 1996: Theorizing a new agenda for architecture; an anthology of architectural theory 1965-1995. Princeton architectural press, New York. 243 Nevanlinna, A. K. 1996: Interpreting Nairobi; the cultural study of built forms. Soumen Historiallinen Seura, Helsinki. Nguluma, H. M. 2003: Housing Themselves; transformation, modernisation and spatial qualities in informal settlements in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Doctoral thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. NISCC, 1997: A development Strategy for Nairobi’s Informal Settlements. Republic of Kenya, Nairobi. Obudho, R. A and Aduwo, G. O. 1992: The nature of the urbanisation process and urbanism in the city of Nairobi, Kenya. African Urban Quarterly, Vol.7, No.1/2: 50-62. O’connor, A. 1983: The African City. Hutchison, London Ogot, B. A. and Ochieng, W. R. (Eds). 1996: Decolonisation and Independence in Kenya, 1940-1993. E.A.E.P, Nairobi, James Currey, London. Olima, W. H. A. 1993: The land use planning in provincial towns of Kenya; A case study of Kisumu and Eldoret towns. Doctoral thesis, University of Dortmund. Payne, G. 1973: Functions of Informality; A case study of squatter settlements in India. Architectural Design Vol.XLIII No.8 :494-503 Peattie, L. 1996: The informal sector in Latin America. In Regional Development Dialogue, Vol.17, No.1, Spring 1996:58-65 Portes, A. et al.(Eds) 1989: The informal economy: studies in advanced and less developed countries. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. Rakodi, C. (Ed). 1997: The Urban Challenge in Africa; Growth and management of it’s large cities. United Nations University Press; Tokyo, New York, Paris. Reardon, P. 2001: Emerging Markets; a strong new voice. Journal of Global Financial Markets, Vol.2, No.1: 12-15. Reiss Jr, A. J. 1956: Urbanism as a way of life in Community life and social policy Wirth, E. et al. (Eds). University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Ribbeck, E. 2002: Informal Modernism; Spontaneous building in Mexico City. HVA-Grafische Betriebe GmbH, Heidelberg. Robbins, E. and El-Khoury, R. (Eds). 2004: Shaping the city; studies in history, theory And urban design. Routledge, London, New York. 244 Rogerson, C. M. 1996: Urban poverty and the informal economy in South Africa’s economic heartland. Environment and Urbanisation, Vol.8 No.1 April 1996. Ross, M. H. 1975: Grass roots in an African city; political behaviour in Nairobi. MIT Press, Cambridge- Massachusetts Rossi, A. 1982: The architecture of the city. MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, London. Smuels, I. et al. 2004: Urban Forms; the death and life of the urban block. Architectural Press, Oxford. Sanya, T. 2002: A study of Informal Settlements in Kampala City. Masters Thesis, University of Stuttgart. Schon, D. 1983: The reflective Practitioner. Basic Books, New York. Simone, A. M. 2002: Opportunities, risks and problems in the urban sphere. African Societies, E-magazine issue No.2 July 31, 2002. Simone, A. M. 2003: Moving towards uncertainty; migration and the turbulence of African urban life. Paper prepared for the conference on African Migration in Comparative perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa, 4-7 June 2003. Sitte, C. 1965: City Planning according to Artistic Principles. Translated by Collins, G. R. and Collins, C. C. Phaidon Press, London Skar, H. O. (Ed), 1985: Anthropological contributions to planned change and development. Gothenburg Studies in Social anthropology; 8. Goteborg. Small, I. 1991: Conditions for criticism; authority, knowledge and literature in the late nineteenth century. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Soja, E. W. 1994: “Los Angeles 1962-1992: The Six Geographies of Urban Restructuring” in Scott, A. Soja, E. W. and Weinstein (Eds), Los Angeles: Geographical Essays, University of California Press, Los Angeles and Berkeley. Soja, E. W. 1989: Post-modern geographies; the reassertion of space in critical social theory. Verso, London. Soja, E. W. 1968: The geography of modernisation in Kenya; a spatial analysis of social, Economic, and political change. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse. Soliman, A. M. 2002: Typology of informal housing in Egptian cities; taking account of diversity. International Development Planning Review, IDPR, 24(2), 245 2002: 177-201. Stren, R. 1972; The evolution of housing policy in Kenya. In Urban Challenge in East Africa, ed. John Hutton. East African Publishing House, Nairobi. Susser, I. (Ed). 2002: The Castells reader on cities and social theory. Blackwell Publishers, Malden, Massachusetts-USA, Oxford-UK. Syagga, P. M. 2002: UNCHS/GOK slum upgrading project; Nairobi situation analysis. Government of Kenya, Nairobi. Syagga, P. M. 2002b: Rental assessment in Nairobi slums. Government of Kenya, Nairobi. Thornton White, L. W. et al. 1948: Nairobi; Master Plan for a colonial capital. A report Prepared for the municipal council of Nairobi. Her Majesty’s stationery office, London. Tipple, G. 2000: Extending themselves; user initiated transformations of governmentbuilt housing in developing countries. Liverpool University Press, UK. Tomasi, L. (Ed), 1998: The tradition of the Chicago School of Sociology. Ashgate, Aldershort. Turner, J. F. C. 1976: Housing by people; Towards autonomy in building environments. Marion Boyers, London. Turner, J. F. C. and Fichter, R. (Eds), 1968: Freedom to build: dweller control of the housing process. Macmillan, New York. UNCHS(Habitat), 2003: The challenge of slums; Global Report on Human Settlements. Earthscan, London. UNCHS(Habitat), 2001: Cities in a Globalising World; Global Report on Human Settlements. Earthscan, London. UNCHS(Habitat), 1996: An Urbanising World; Global Report on Human Settlements. Oxford University Press, Oxford. UNDP, 2002: Kenya Human Development Report 2001; Addressing social and economic Disparities for human development. Nairobi Velez, D. 1983: Late Nineteenth Century Spanish Progressivism: Arturo Soria’s Linear City. Journal of Urban History Vol.9 No.2:131-164 Vidrovitch, C. C. 1991: The process of urbanisation in Africa; from the origins to the 246 beginning of independence. African studies review, Vol.34, No.1, April 1991: 1-98. Warah, R. 2003: Slums are the heartbeat of cities; Daily Nation, Monday October 6, 2003. Ward, P. M. 1982: Self-help housing: A critique. Mansell Publishing Company, London. Weber, M. 1958: The nature of the city. Translated by Don, M. and Gertrud, N. The Free Press, Glencoe, Illinois Wells, J. and Wall, D. 2003: The expansion of employment opportunities in the building construction sector in the context of structural adjustment; some evidence from Kenya and Tanzania. Habitat International 27 (2003): 325-337. Weru, J. 2004: Community federations and city upgrading: the work of Pamoja Trust and Muungano in Kenya. Environment and Urbanisation, Vol.16, No.1: 47-62. Wiebenson, D. 1969: Tony Garnier: the cite industrielle. Studio Vista, London. World Bank and Padco, 1981: The Bertand Model: a model for the analysis of alternatives for low income shelter in the developing world. Urban Development Department, Technical paper No.2, Washington, D. C. Yin, R. 1994: Case study research; design and methods. Sage Publications, London. Zwanenberg, R. M. A. Van, and King, A. 1975: An economic history of Kenya and Uganda 1800-1970. Macmillan, London 247