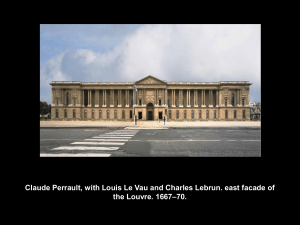

YUKSEL Zeynep Yuksel INTERPRETATION OF PAUL CÉZANNE'S STILL LIFE WITH APPLES Still life paintings have always been a challenge for art historians to analyze in terms of their subject matter. The Academy has questioned still life paintings as presenting subject matter unworthy of scrutiny. Of course, objects of daily life—such as flowers, fruits and vases—have been a subject matter and an inspiration for artists since antiquity. However, what makes still life paintings so special is the huge range of objects depicted, but they are considered under one single subject heading: still life. In the hierarchy of subject matter, still life has always been at the bottom; for the Academy, still life paintings do not depict a significant event or story to make the subject matter worthy of deep consideration. More recently, however, modern art critics have been more convinced that still life paintings are worth looking at and the genre worth analyzing. Still life is rated low on two counts: genre and medium. It usually has as its background a humble household activity or a daily studio exercise. “Like still life, it tends to be relatively small in size. Like still life, it has something of the feminine about it. As with still life, moreover, its subjects are generally of low standing. And as with still life, so with watercolor: it is neither that genre nor that medium.” 1 Armstrong states the importance of still life paintings and the subject matter in our lives with this sentence. Most still life paintings that were painted at the time were very small in size, and the setting of the painting was 1 Carol Armstrong and Paul Cézanne, Cézanne in the Studio: Still Life in Watercolors (Los Angeles: J.P. Getty Museum, 2004), 2. !1 YUKSEL always the interior of the house, where it was considered private and, like Armstrong says, had something of the feminine about it. Norman Bryson, the author of Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting, defines still life paintings thus: "the life of the table, of the basic creaturely acts of eating and drinking, of the artefacts which surround the subject in her or his domestic space, of the everyday world of routine and repetition, at a level of existence where events are not at all the large-scale, momentous events of History, but the small-scale, trivial, forgettable acts of bodily survival and self-maintenance.”2 Furthermore, he argues that our attitude towards still life paintings should change from those traditional ways of analyzing paintings. Throughout his book, he argues that still life paintings contain more complex details than initially appears to be the case. He suggests that female artists are more comfortable illustrating an interior still life than are male artists. He compares Cézanne’s painting style to “insistence on non-participation in the domestic space as a condition of access to high art”3, an artist who, in most of his still life paintings, does not contain the actual scene of interior. On the other hand, female artists of the time were displaying the whole object and the everyday space rather than just a part of it. Moreover, like Bryson, Meyer Schapiro looks at Cézanne’s still life painting from a non-traditional perspective. Meyer Schapiro, writing in 1968, examines a subjective critique 2 Norman Bryson, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (London: Reaktion, 1990), 165. 3 Byrson, Looking at the Overlooked, 165. !2 YUKSEL of Cézanne’s still life. By being subjective about the subject matter, he applies psychoanalytical observation to the paintings. The theme of apples and love allows Schapiro to analyze more of Cézanne’s work and its underlining sexual nature. He uses the writings of Zola—a good friend of Cézanne—to relate the psychological aspect of the artist’s works. Cézanne’s interaction with apples goes back to his student times in Aix. Zola talks about his friendship with Cézanne and tells that, for Cézanne, apples symbolized love and great friendship. Schapiro talks about Cézanne’s close relationship to Zola, which was not only a friendship but also part of his own dream of love. 4 The subject of love was always a part of Cézanne’s paintings. As Schapiro says, it was “a question of idealism versus realism, idealism being the name for platonic love and realism for the physical experience Cézanne could only imagine.” 5 Cézanne in most of his paintings tried to depict the realism of objects and posed his question of realism versus idealism. Unlike other authors of the time, Schapiro does not look for the originality or the techniques in Cézanne’s works, but rather at the meaning and the more personal aspect of the subject to Cézanne. Schapiro often claims that Cézanne’s paintings are sexual. In his earlier paintings especially, the theme of sexuality can be sensed when he depicts nude models, but later in his later works this aspect lesson and had disappeared by the end of the 1870s. 6 To his human models, he would often say “Be an apple,” where he meant that the model should stay 4 Meyer Schapiro, “The Apple of Cézanne: An Essay on the Meaning of Still-Life,” in Modern Art—19th and 20th Centuries—Selected Papers, (New York, 1979), 29–30. 5 Schapiro, “The Apple of Cézanne”, 9. 6 Schapiro, “The Apple of Cézanne”, 10. !3 YUKSEL still and be mute so that he would not have to see their personality or hear their thoughts: instead, just be like an apple and stay there. Cézanne’s approach to his models leads Schapiro to conclude the sexual and psychological intricacies of Cézanne's apple motif and his portrayals of women. As he adds, Cézanne was never comfortable painting a nude woman figure and this allowed him to work on another subject, which was still life. In Cézanne’s pre-still life paintings, he often portrayed nude models with an apple— described by Shapiro as “real and symbolic of an interior drama” 7—and Schapiro adds that these paintings and drawings of still life objects, mainly apples, represented an erotic sense and an unconscious desire. 8 Cézanne reshaped his conscious and unconscious needs, just like when he questioned realism versus idealism, and he applies this approach to his paintings. Schapiro often relates Cézanne’s apples to his desire. Moreover, Schapiro adds: “The apples to which he gave almost lifelong attention are still cited as proof of the insignificance of the objects represented by the painter. They are nothing more, it is supposed, than "pretexts" of form.”9 Cézanne’s studied the various shapes and colors of apples and he applied his studies to his paintings, lending a sense of richness and harmony to the represented objects. Roger Fry, looking at one of Cézanne’s still life paintings, observed the complexity and richness of Cézanne’s works and saw the inconsequential subject matter as the keystone 7 Schapiro, “The Apple of Cézanne”, 11. 8 Schapiro, “The Apple of Cézanne”, 12. 9 Schapiro, “The Apple of Cézanne”, 16. !4 YUKSEL of his work. He commented: “the ideas and emotions associated with the objects represented are, for the most part, so utterly commonplace and insignificant that neither artist nor spectator need consider them. It is this fact that makes the still-life so valuable to the critic as a gauge of the artist’s personality.” 10 Cézanne’s objects are formed in a very modest way, and Fry argues that Cézanne and his objects were a direct expression of the artist’s interior life, and this approach made the objects more meaningful. Furthermore, contrary to Fry’s argument on Cézanne’s objects, Shapiro argues that Cézanne’s apples are important and symbolic of an unconscious desire. For Shapiro, the still life was as important as the religious and historical paintings. In fact, the painting of still life has a humanist narrative when framing the objects in its field. 11 Cézanne applied different painting techniques. He created very solid forms of objects and avoided a traditional perspective method in his paintings. His deep study of geometry in painting led him to become a master of perspective. He avoided the geometrical perspective system that was created during the Renaissance and accomplished another perception of his objects where the objects sat very freely and each object was harmonious with the whole. This new perception method in most of his paintings creates a sense of intimacy between the viewer and the space inhabited by the objects. One of Cézanne’s famous dictums was that: “The eye becomes concentric by looking and working. I mean to say that in an orange, an apple, a ball, a head, there’s a culminating 10 Armstrong 11 and Cézanne, Cézanne in the Studio, 2. Schapiro, “The Apple of Cézanne”, 29–30. !5 YUKSEL point is always closest to our eye; the edges of objects flee toward a centre placed on our horizon.”12 Cézanne was always interested in the geometric shapes and the different aspects of the objects. In other words analogous to his famous dictum, he was more interested in rounded objects than the angular. That is why one of the most significant concerns for Cézanne was our perception of his paintings and the objects within the frame. Paul Cezanne, Still life with Apples, c.1877-78, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum The still life paintings had always interested the eye in terms of the display of the objects. In most of Cézanne’s paintings, the viewer’s perception of the different textures of the objects can be easily differentiated. He would usually illustrate glassware and metalware in front of a different sort of textural background. The eye has a round shape, not flat, and we see the objects from different angles, and so our stance is our horizon and the perception of 12 Armstrong and Cézanne, Cézanne in the Studio, 56. !6 YUKSEL the object will be different. The effect Cézanne managed to achieve in t Still Life with Apples (circa 1877–78) is of a different natural background and a shift in our perception of apples. Jean Simeon Chardin (French, 1699-1779) Still life with Peaches, A Silver Goblet, Grapes and Walnuts, c.1760, Los Angelas, J. Paul Getty Museum Furthermore, the warm color of apples make them more visible, as the background and table are cooler grass and browns, thus creating the illusion of movement. The apples look solid and round and this creates a sense of realism. Cézanne’s paintings were close to the real and he created “true-to-life representation”.13 He wanted something not mechanical or simply optical—he wanted to develop an awareness and sensation of his creations instead of a mechanical representation. 13 D. H. Lawrence and James T. Boulton, Late Essays and Articles (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 211. !7 YUKSEL The origin of Cézanne’s still life painting goes all the way back to the eighteenth century French painter Jean-Simeon Chardin. Cézanne used his techniques to arrange his objects precisely. Gustave Courber, Manet and Fantin-Latour are also known for their still life and they invoked Chardin’s style in their composition. Chardin’s Still Life with Peaches, a Silver Goblet, Grapes and Walnuts depicts a very humble scene with some peaches on top of one another, walnuts placed to the left hand side of the peach pyramid, and some green and purple grapes in the center of the painting. The painting has no signs of luxury elements. He brought this middle-class feel to French still life.14 These qualities of Chardin were also applied by Cézanne to his still life paintings. However, Cézanne did not take all his style from Chardin. For Chardin, the mass of the objects and their relationship to their structure were very important in his compositions; however, for Cézanne, “it was a kind of perceptual test for the solitary eye of the viewer: how to distinguish one thing from another, how to distinguish the figure from its ground, how to read the circuit and invisible back of an object from what is given on the flat plane of the paper”.15 He constructed a different composition and transformed it into a perception of the subject. Illustrations of the daily life of the middle class is another element that Chardin used and which, later on, Cézanne also applied to his still life paintings. Unlike all the Impressionist painters of that time who mostly illustrated high class meals and manners, Cézanne preferred to show middle class life to his viewers. 14 Armstrong and Cézanne, Cézanne in the Studio, 54. 15 Armstrong and Cézanne, Cézanne in the Studio, 55. !8 YUKSEL Paul Cezanne, The Basket of Apples, c.1890-1894, Art Institute of Chicago The Basket of Apples is another example of Cézanne’s still life. What fascinated the historians later in the century was that when they looked in more detail at Cézanne’s painting, they realized the strangeness of his paintings—the oddness of where the everyday life objects occurred together in such a way. This still life painting has an aspect of randomness and, at first, these objects seem like they were placed accidentally. It looks like accidental; but when it is examined deeply, each object harmonizes with every other; the apples in the basket are harmonized with the apples in the tablecloth, the apples in the tablecloth harmonized with the regular pattern of the biscuits. In the end, it can be seen as a balanced organization of the objects. However, some parts of the painting are unbalanced and unstable if we examine each object one by one. !9 YUKSEL Firstly, the left side and the right side of the tablecloth are not even and not on the same horizontal line. This similar unevenness can also be seen at the back of the table, and there is an odd distance between the basket and the biscuits. The bottle of wine seems like it is not on the plain platform and it gives a sense that it is about to fall. A further strange detail of the biscuits is the way they are placed: it seems like each layer has a different viewpoint. It feels like the bottom layers can be seen from the side and the top layers from the top, as if the viewer is standing and looking from two directions at the same time. Cézanne often defended that perception should focus only on one point but also have different perceptions from the top, side and bottom at the same time, just like the camera does when we take a photo with it. He was inspired by this idea and applied this technique to his paintings. Some critics have been very skeptical of still life as a genre in art. For an artist, it has more meaning than just an artistic genre. For them, it is a work of self-expression, and for Cézanne it was more of an experiment with the space than a genre in art. One painting can convey a range of feelings of an artist. Even just a simple daily life object may symbolize a wealth of thoughts. Schapiro assesses that this genre can be created anytime, and even one single object may be interpreted in so very many different ways. !10 YUKSEL BIBLIOGRAPHY Books Armstrong, Carol M, and Paul Cézanne. Cézanne in the Studio: Still Life in Watercolours. Los Angeles: J.P. Getty Museum, 2004. Print. Bryson, Norman. Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting. London: Reaktion, 1990. Print. Lawrence, D H, and James T. Boulton. Late Essays and Articles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Print. Articles Schapiro, Meyer. Modern Art, 19th & 20th Centuries: Selected Papers. New York: George Braziller, 2011. Print. !11