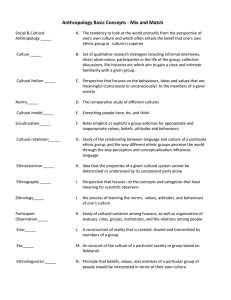

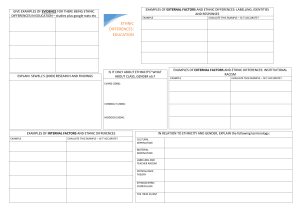

Anthropology Module: Culture, Diversity, and Inter-Ethnic Relations

advertisement