Uploaded by

princeehsanullah786

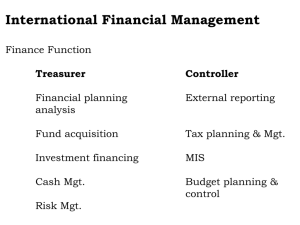

Globalization & Multinational Firms: International Finance

advertisement