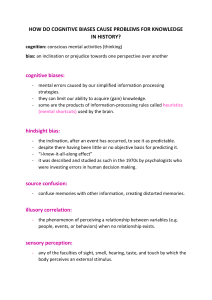

IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko Module 3 – Cognitive Bias (Start with 188 bias infographic before moving to ppt #1) Cognitive Bias Cognitive biases are inherent in the way we think, and many of them are unconscious. Identifying the biases you experience and purport in your everyday interactions is the first step to understanding how our mental processes work, which can help us make better, more informed decisions. These are things that affect workplace culture, budget estimates, deal outcomes, and our perceived return on investments within the company. The many types of cognitive biases serve as systematic errors in a person’s subjective way of thinking, which originate from that individual’s own perceptions, observations, or points of view. There are different types of biases people experience that influence and affect the way we think and behave, as well as our decision-making process. How Does Cognitive Bias Impact the Way We Think? Biases make it difficult for people to exchange accurate information or derive truths. A cognitive bias distorts our critical thinking, leading to possibly misconceptions or misinformation that can be damaging to others. Biases lead us to avoid information that may be unwelcome or uncomfortable, rather than investigating the information that could lead us to a more accurate outcome. Biases can also cause us to see patterns or connections between ideas that aren’t necessarily there. Out of the 188 cognitive biases that exist, there is a much narrower group of biases that has a disproportionately large effect on the ways we do business. Cognitive Bias Examples in Business Today’s infographic from Raconteur aptly highlights 18 different cognitive bias examples that can create particularly difficult challenges for company decision-making. The list includes biases that fall into categories such as financial, social, short term-ism, and failure to estimate: Financial biases These are imprecise mental shortcuts we make with numbers, such as hyperbolic discounting – the mistake of preferring a smaller, sooner payoff instead of a larger, later reward. Another classic financial cognitive bias example is the “Ostrich effect”, which is where one sticks their head in the sand, pretending that negative financial information simply doesn’t exist. Social biases Social biases can have a big impact on teams and company culture. For example, teams can bandwagon (when people do something because other people are doing it), and individual team members can IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko engage in blind spot bias (viewing oneself as less biased than others). These both can lead to worse decision-making. Short Term-isms One way to ensure a business that doesn’t last? Engage in short term-isms – these are biases that gear your business towards decisions that can be rationalized now, but that don’t add any long-term value. Status quo bias and anchoring are two ways this can happen. Failure to Estimate So much about business relies on making projections about the future, and the biases in this category make it difficult to make accurate estimates. Cognitive bias examples here include the availability heuristic (just because information is available, means it must be true), and the gambler’s fallacy (future probabilities are altered by past events). Cognitive Bias Examples 1. Confirmation bias. This type of bias refers to the tendency to seek out information that supports something you already believe, and is a particularly pernicious subset of cognitive bias—you remember the hits and forget the misses, which is a flaw in human reasoning. People will cue into things that matter to them, and dismiss the things that don’t, often leading to the “ostrich effect,” where a subject buries their head in the sand to avoid information that may disprove their original point. *Complete confirmation bias activity (video) now. The Most Common Cognitive Bias Activity Experience Confirmation Bias The following video illustrates the Wason Rule Discovery Test to introduce the idea of confirmation bias. Play “Can You Solve This?”. Stop the video at 1:25 and ask students if they can guess the rule. Ask them to explain their thinking. Then play the video to the end. Why do people have trouble guessing the rule? What can we conclude from this video about the challenges we face when we try to make sense and judge the veracity of the news and information that we receive via friends, the Internet, social media, etc.? 2. The Dunning-Kruger Effect. This particular bias refers to how people perceive a concept or event to be simplistic just because their knowledge about it may be simple or lacking—the less you know about something, the less complicated it may appear. However, this form of bias limits curiosity—people don’t feel the need to further explore a concept, because it seems simplistic to them. This bias can also lead people to think they are smarter than they actually are, because they have reduced a complex idea to a simplistic understanding. 3. In-group bias. This type of bias refers to how people are more likely to support or believe someone within their own social group than an outsider. This bias tends to remove objectivity from any sort of selection or hiring process, as we tend to favor those we personally know and want to help. IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko 4. Self-serving bias. A self-serving bias is an assumption that good things happen to us when we’ve done all the right things, but bad things happen to us because of circumstances outside our control or things other people purport. This bias results in a tendency to blame outside circumstances for bad situations rather than taking personal responsibility. 5. Availability bias. Also known as the availability heuristic, this bias refers to the tendency to use the information we can quickly recall when evaluating a topic or idea—even if this information is not the best representation of the topic or idea. Using this mental shortcut, we deem the information we can most easily recall as valid, and ignore alternative solutions or opinions. 6. Fundamental attribution error. This bias refers to the tendency to attribute someone’s particular behaviors to existing, unfounded stereotypes while attributing our own similar behavior to external factors. For instance, when someone on your team is late to an important meeting, you may assume that they are lazy or lacking motivation without considering internal and external factors like an illness or traffic accident that led to the tardiness. However, when you are running late because of a flat tire, you expect others to attribute the error to the external factor (flat tire) rather than your personal behavior. 7. Hindsight bias. Hindsight bias, also known as the knew-it-all-along effect, is when people perceive events to be more predictable after they happen. With this bias, people overestimate their ability to predict an outcome beforehand, even though the information they had at the time would not have led them to the correct outcome. This type of bias happens often in sports and world affairs. Hindsight bias can lead to overconfidence in one’s ability to predict future outcomes. 8. Anchoring bias. The anchoring bias, also known as focalism or the anchoring effect, pertains to those who rely too heavily on the first piece of information they receive—an “anchoring” fact— and base all subsequent judgments or opinions on this fact. 9. Optimism bias. This bias refers to how we as humans are more likely to estimate a positive outcome if we are in a good mood. 10. Pessimism bias. This bias refers to how we as humans are more likely to estimate a negative outcome if we are in a bad mood. 11. The halo effect. This bias refers to the tendency to allow our impression of a person, company, or business in one domain influence our overall impression of the person or entity. For instance, a consumer who enjoys the performance of a microwave that they bought from a specific brand is more likely to buy other products from that brand because of their positive experience with the microwave. 12. Status quo bias. The status quo bias refers to the preference to keep things in their current state, while regarding any type of change as a loss. This bias results in the difficulty to progress or accept change. IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko The Father-Son Activity Another useful awareness activity for unconscious bias training taken from the social psychological literature is the Father/Son activity, adapted from Pendry, Driscoll, & Field (2007). In this activity, participants are instructed to solve the following problem: “A father and son were involved in a car accident in which the father was killed and the son was seriously injured. The father was pronounced dead at the scene of the accident and his body was taken to a local morgue. The son was taken by ambulance to a nearby hospital and was immediately wheeled into an emergency operating room. A surgeon was called. Upon arrival and seeing the patient, the attending surgeon exclaimed “Oh my God, it’s my son!’ Can you explain this?” Around 40% of participants who are faced with this challenge do not think of the most plausible answer—being the surgeon is the boy’s mother. Rather, readers invent elaborate stories such as the boy was adopted and the surgeon was his natural father or the father in the car was a priest. As such, the exercise illustrates the powerful pull of automatic, stereotyped associations. For some individuals, the association between surgeon and men is so strong that it interferes with problem-solving and making accurate judgments. This exercise leads well into an ensuing discussion on the automaticity of stereotypes and the distinction between explicit and implicit bias. From here, the discussion can move to explore ways of controlling or overcoming automatic bias. Also, because some of the participants will solve the problem with the most plausible reason, the exercise highlights individual differences in stereotyping and opens a discussion into why stereotypes differ across individuals. How to Reduce Cognitive Bias Even though cognitive biases are pervasive throughout every system, there are ways to address your bias blind spots: 1. Be aware. The best way to prevent cognitive bias from influencing the way you think or make decisions is by being aware that they exist in the first place. Critical thinking is the enemy of bias. By knowing there are factors that can alter the way we see, experience, or recall things, we know that there are additional steps we must take when forming a judgment or opinion about something. 2. Challenge your own beliefs. Once you’re aware that your own thinking is heavily biased, continuously challenge the things you believe is a good way to begin the debiasing process— especially when receiving new information. This can help you expand your pool of knowledge, giving you a greater understanding of the subject matter. 3. Try a blind approach. Especially in the case of observer bias, researchers conduct blind studies to reduce the amount of bias in scientific studies or focus groups. By limiting the amount of influential information a person or group of people receive, they can make less affected decisions. IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko SPACE2 Model of Mindful Inclusion In social interactions, human beings process information via two routes. One route is automatic, largely driven by emotional factors, and activates well-established stereotypes. Our automatic social processing happens so quickly that it is below our level of consciousness. Automatic social processing can influence our immediate judgments and behaviours without us even knowing it. In social settings, stereotypes and associated prejudices and discriminatory responses occur fast and outside of conscious awareness. However, the good news is that we can override our reflexive responses with controlled and deliberate thought or reflection. When we are motivated to be fair and unprejudiced because of either a strong internalised belief that it is morally correct to treat others fairly or because of strong social norms and legal restrictions against expressed prejudice and discrimination, we can engage controlled mental processes to override biased reflexive responses. The SPACE2 Model of Mindful Inclusion is a collection of six evidence-based strategies that activate controlled processing and enable individuals to detect and override their automatic reflexes: Slowing Down — being mindful and considered in your responses to others Perspective Taking — actively imagining the thoughts and feelings of others Asking Yourself — active self-questioning to challenge your assumptions Cultural Intelligence— interpreting a person’s behaviour through their cultural lens rather than your own Exemplars — identifying counter-stereotypical individuals Expand — the formation of diverse friendships While prompting individuals to remember the six techniques, the SPACE2 acronym reinforces a key message—to manage bias, individuals must create space between their automatic reflexes and their responses. (i) Slowing Down Because controlled processing is deliberate and much slower than automatic processing, there remains a possibility for reflexive and immediate biased responses, even in individuals who endorse egalitarian values, particularly when under time pressure. Studies show greater discrimination in selecting applicants from resumes when the assessors report feeling rushed. Individuals who are seeking to manage their biases must slow down their responses and refrain from making key talent decisions when rushed. Also, as controlled processing requires more mental resources, when an individual is mentally taxed or fatigued, it is less likely that their implicit biases will be effectively overridden. That is, when we have limited cognitive resources available for social perception (for example, because we are distracted by another mentally-taxing task, or under emotional or physiological stress), we tend to rely more on stereotypes to make judgments and guide our behaviours. Don’t make key decisions when busy, anxious or in a negative mood. IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko Unconscious bias is also more likely to manifest as discriminatory behavior when it can be justified or rationalised on non-discriminatory grounds. When assessing the suitability of male and female candidates for different roles, for example, assessors are more likely to redefine the criteria that constitutes “merit” for the role to fit the profile of the candidate of the preferred gender. Act with a conscious intent to be fair and be particularly vigilant in situations where your biases are likely to be most influential. Conscious attempts at suppressing bias are more effective at inhibiting some prejudiced and discriminatory responses but not others. Conscious intention can help to overcome our verbal responses, but our non-verbal behaviour and judgments are much more difficult to control. Subtle discriminative responses—for example, feelings of discomfort, exclusion, and avoidance—may leak out during our exchanges with outgroup member. Mindfully monitor your micro-biases, including, eye contact, smiling, mobile use, body language, interruptions, when interacting with people who are different to you. (ii) Perspective-taking Neurocognitive studies have demonstrated that we all possess an ability to mimic automatically the emotions, thoughts, and actions of others. From an evolutionary perspective, this ability to synchronise our intentions and behaviours with others enhances our social functioning that, in turn, increases our chances of survival. Research shows, however, that although we automatically simulate the mental and motor activity of ingroup members, this process is much less responsive to outgroup members. Fortunately, with conscious effort, we can make up for this deficit in intergroup sensitivity. Perspectivetaking refers to the ‘active contemplation of other’s psychological experiences’—that is, thinking and imagining the feelings and viewpoints of others. It is now well-established that perspective-taking has positive implications for intergroup relations including increased empathy, reduction of unconscious prejudiced attitudes and discriminatory behaviours, and decreased activation of negative stereotypes. Perspective-taking works by enhancing ‘self-other overlap’—the merging of one’s cognitive representations of their self-concept with representations of outgroup members. In this way, social category boundaries become blurred and they become me. Outgroup members are now perceived to be more like the self, and are more likely to be afforded the positive favoritism usually reserved for ingroup members. This effect can generalise to other outgroup members because the individual is perceived as a prototype for the wider group. (ii) Ask Yourself Prompts or questions that encourage us to examine our assumptions when assessing others or making decisions that will impact their careers helps to bring our biases into conscious awareness. Howard Ross suggests that individuals engaged in high-stakes decision-making about others should always stop to ask themselves: Does this person remind you of yourself? Does this person remind you of anyone else? Is this positive or negative? Are there things about this person that particularly influence your impression? Are they really relevant to the job? IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko What assessments have you already made? Are these grounded in solid information or your assumptions? Also, pay attention to objective information. Focus on skills and actively challenge any assessments you have made by seeking evidence that backs up or contradicts that assessment. (iv) Cultural intelligence Psychologists label the tendency to attribute a person’s behaviour to innate character flaws or personality traits rather than to contextual influences the fundamental attribution error. When explaining a person’s behaviour, we typically give more weight to dispositional influences than external causes—John is late because he is unreliable, rather than John is late because of bad traffic. Although our behaviours are often influenced by factors external to the self, we are quick to judge a person’s actions as reflective of their character rather than situational causes. This is because people are the most salient object to us during an exchange, whereas contextual influences are less obvious. When we work across cultures, the risk of making the fundamental attribution error is high. When working with culturally diverse others, we routinely attribute their behaviours to innate dispositions rather than to their cultural conditioning. We can counter the risk of making the fundamental attribution error when working across cultures by actively seeking culturally appropriate explanations for behaviour. While perspective-taking for empathy focuses on the emotions of the other person without reference to cultural differences, making culturally appropriate attributions focuses on understanding the other person’s perspective through their cultural frame of reference. Imagining the world from the perspectives of others helps you transcend the automaticity of your own cultural framework and to interpret their intentions and behaviours more accurately, reducing misunderstandings, misattributions, and conflict. Differences are less likely to be labeled as deviant, stereotyping and bias is reduced, communication is enhanced, and suspicion and distrust are minimised. Prompts can help individuals to improve their cultural perspective-taking by encouraging them to reflect on how culture might be affecting their counterpart’s values and beliefs, for example, ‘Before you decide how to respond in this interaction, write down a few sentences describing your counterpart’s interests and concerns as a person living within their culture. Now consider how your counterpart’s behaviours and decisions in this situation may be guided by his or her cultural values and beliefs’. Prompts are useful when planning for intercultural interactions. They can also be used to encourage monitoring in real-time exchanges with others. (v) Exemplars Multiple studies have shown that the accessibility of automatic and unconscious stereotypes is reduced by engaging in counter-stereotypical imagery. In one example, being instructed to imagine a strong women led to less accessibility of an automatic ‘weak-women’ stereotyped association as measured in the implicit association test. Within a training environment, counter-stereotypical imaging can be introduced as a unconscious bias intervention. Outside of the classroom, using communication channels to celebrate and acknowledge the successes of individuals from underrepresented or stereotyped IB103 Instructor: A. Fedurko groups can help to dismantle implicit bias by weakening the association between the group and the stereotyped behaviour. (v) Expand Studies indicate that the formation of intergroup friendships can help to dismantle social categorisations and decrease bias. Activities that encourage diverse individuals to share information about their unique backgrounds, experiences, and skills promotes individuation of outgroup members such that they come to be considered as individuals rather than as a member of a broader social category. Under this approach, the focus moves from “one of them” to “you and me”. There is another mechanism by which relational-based activities decrease the tendency for bias. Studies have shown that social categories can become more inclusive by inducing a positive mood state. There are a couple of reasons why this occurs. Firstly, we are attracted to people that we associate with feeling good. Secondly, a positive mood enhances our cognitive flexibility and leads to broader and more inclusive categorisations. What Is the Difference Between Logical Fallacy and Cognitive Bias? Cognitive biases are often confused with logical fallacies. A cognitive bias refers to how our internal thinking patterns affect how we understand and process information. A logical fallacy refers to an error in reasoning that weakens or invalidates an argument. Cognitive biases are systematic errors in a person’s subjective way of thinking, while logical fallacies are about the errors in a logical argument. Root-Cause Analysis Refer to Business Analysis Techniques Guide – Root Cause Analysis.