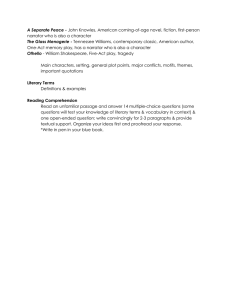

Glencoe Literature: Reading with Purpose - Middle School Textbook

advertisement