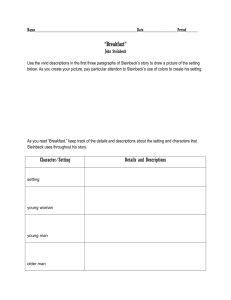

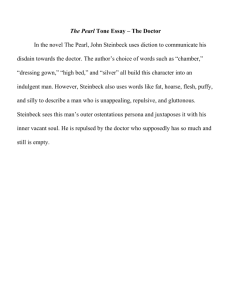

Before You Read Breakfast Meet John Steinbeck Very few people ever “mature. . . . But sometimes . . . awareness takes place—not very often and always inexplainable. There are no words for it because there is no one ever to tell. This is a secret not kept a secret, but locked in wordlessness. The craft or art of writing is the clumsy attempt to find symbols for the wordlessness. ” —Steinbeck John Steinbeck was born and raised in Salinas, California, a small town nestled in a sprawling valley of lettuce farms. Bright and popular, Steinbeck was the president of his senior class in high school, wrote for the school newspaper, and played sports. He was accepted to Stanford University, but yearning for more life experiences, he drifted in and out of college, never earning a degree. Instead, he wrote and worked, taking jobs as a ranch hand, a factory worker, a sales clerk, a freelance newspaper writer, a construction worker, and a farm laborer. Steinbeck published four novels by the time he was thirty-three. His fourth book, the novel Tortilla Flat, was his first publicly acclaimed book. Set in his familiar Salinas Valley, it vividly and humorously describes the joys and sorrows of a group of unemployed men. The following year, Steinbeck used his experiences as a factory worker to produce and publish his next success, a novel entitled In Dubious Battle, which includes realistic and violent scenes based on labor strikes in California. Perhaps Steinbeck’s greatest work is the novel The Grapes of Wrath, written as the United States 796 UNIT 6 was getting back on its feet after the Great Depression of the 1930s. This 1940 Pulitzer Prize winner traces the difficult journey of poor farmers from the Dust Bowl poverty of Oklahoma to the rich farmland of California’s Salinas Valley. There the farmers suffer tragically from injustice handed out by powerful landowners and corrupt officials. Today, The Grapes of Wrath is universally respected for its depiction of the individual’s quest for justice and dignity. Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962. He privately expressed fears about winning the prize, noting that authors whom he respected, including William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway, had produced no further major works after receiving it. Six years after receiving the prize, Steinbeck died, without publishing another work. [T]he writer is delegated to declare and to “celebrate [humanity’s] proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit—for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion, and love. ” “ [T]he free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, religion, or government which limits or destroys the individual. This is what I am and what I am about. ” —Steinbeck John Steinbeck was born in 1902 and died in 1968. How did you react to this story? Jot down your reactions to the characters, their encounter, and the setting. What are some of your favorite sensory details in this story? How did these sensory details affect your reading of the story? Writing About Literature Lively Description Steinbeck creates vivid pictures of the setting by using specific, dramatic adjectives and verbs, such as “there was a flash of orange fire seeping out of the cracks of an old rusty iron stove.” Select another example of vivid description from the selection. Describe the scene as you see it in your mind, adding details to your mental picture, if you wish “Morning,” said the young man. The water was slowly drying on their faces. They came to the stove and warmed their hands at it. The girl kept to her work, her face averted and her eyes on what she was doing. Her hair was tied back out of her eyes with a string and it hung down her back and swayed as she worked. She set tin cups on a big packing box, set tin plates and knives and forks out too. Then she scooped fried bacon out of the deep grease and laid it on a big tin platter, and the bacon cricked3 and rustled as it grew crisp. She opened the rusty oven door and took out a square pan full of high big biscuits. When the smell of that hot bread came out, both of the men inhaled deeply. The elder man turned to me, “Had your breakfast?” “No.” “Well, sit down with us, then.” That was the signal. We went to the packing case and squatted on the ground about it. The young man asked, “Picking cotton?” “No.” “We had twelve days’ work so far,” the young man said. The girl spoke from the stove. “They even got new clothes.” The two men looked down at their new dungarees and they both smiled a little. The girl set out the platter of bacon, the brown high biscuits, a bowl of bacon gravy and a pot of coffee, and then she squatted down by the box too. The baby was still nursing, its head 3. Here, cricked means “turned or twisted.” up under her waist out of the cold. I could hear the sucking noises it made. We filled our plates, poured bacon gravy over our biscuits and sugared our coffee. The older man filled his mouth full and he chewed and chewed and swallowed. Then he said, “God Almighty, it’s good,” and he filled his mouth again. The young man said, “We been eating good for twelve days.” We all ate quickly, frantically, and refilled our plates and ate quickly again until we were full and warm. The hot bitter coffee scalded our throats. We threw the last little bit with the grounds in it on the earth and refilled our cups. There was color in the light now, a reddish gleam that made the air seem colder. The two men faced the east and their faces were lighted by the dawn, and I looked up for a moment and saw the image of the mountain and the light coming over it reflected in the older man’s eyes. Then the two men threw the grounds from their cups on the earth and they stood up together. “Got to get going,” the older man said. The younger turned to me. “’Fyou want to pick cotton, we could maybe get you on.” “No. I got to go along. Thanks for breakfast.” The older man waved his hand in a negative. “O.K. Glad to have you.” They walked away together. The air was blazing with light at the eastern skyline. And I walked away down the country road. That’s all. I know, of course, some of the reasons why it was pleasant. But there was some element of great beauty there that makes the rush of warmth when I think of it. Vocabulary 800 avert (ə vurt) v. to turn away or aside UNIT 6 Active Reading and Critical Thinking Responding to Literature Personal Response How did you react to this story? Jot down your reactions to the characters, their encounter, and the setting. Analyzing Literature Recall and Interpret 1. How does the narrator introduce this incident? What are the first things he describes? What do the introduction and the descriptions tell you about the narrator? 2. What observations does the narrator make about the family of migrant workers? What seems to be important to the family? Explain. 3. What do the narrator and the migrant workers talk about? What tone is conveyed by the family’s words and actions? (See Literary Terms Handbook, page R16.) Support your answer with details from the story. 4. What does the narrator say about his memory at the end of the story? What might his attachment to this memory suggest about his life? What deeper understanding or awareness of life does he seem to gain? Evaluate and Connect 5. Reread your journal entry from the Reading Focus on page 797. What new details would you like to add to your description after reading “Breakfast”? 6. Steinbeck wrote about migrant workers who lived in small, supportive communities. In what ways does Steinbeck portray the narrator as part of such a supportive community? 7. Steinbeck wrote to reach the heart of working people. Explain which aspects of this story might appeal to a farmer, a rancher, or a laborer. 8. What are some of your favorite sensory details (see page R14) in this story? How did these sensory details affect your reading of the story? Literary Criticism According to critic Daniel Aaron, Steinbeck portrays migrant workers as the “preservers of the old American verities, innocent of bourgeois properties, but courteous, trusting, friendly, and generous. . . . What preserved them in the end . . . was a recovery of a neighborly interdependence that an acquisitive society had almost destroyed.” How does Steinbeck portray the workers in “Breakfast”? What effect does their behavior have on the narrator? Discuss your answers in a small group. Literary ELEMENTS Implied Theme The theme of a piece of literature is a dominant idea, often a universal message about life, that the writer communicates to the reader. Authors rarely state a theme outright. Instead, they use an implied theme, letting the main idea or message reveal itself through events, dialogue, or descriptions. In “Breakfast,” the implied theme is built around the narrator’s warm recollection of an encounter with a group of migrant workers. 1. What is the implied theme, or message about life, in this selection? State the implied theme in your own words. 2. What details and descriptions support this theme? • See Literary Terms Handbook, p. R16. Extending Your Response Writing About Literature Interdisciplinary Activity Lively Description Steinbeck creates vivid pictures of the setting by using specific, dramatic adjectives and verbs, such as “there was a flash of orange fire seeping out of the cracks of an old rusty iron stove.” Select another example of vivid description from the selection. Describe the scene as you see it in your mind, adding details to your mental picture, if you wish. History: California Farming Research and prepare a brief report on the different groups of migrant workers in California during the 1900s. Begin with the 1930s and update your report with information about current migrant workers in the state. Include visuals, such as photographs, in your presentation to the class. Save your work for your portfolio. MIDCENTURY VOICES 801