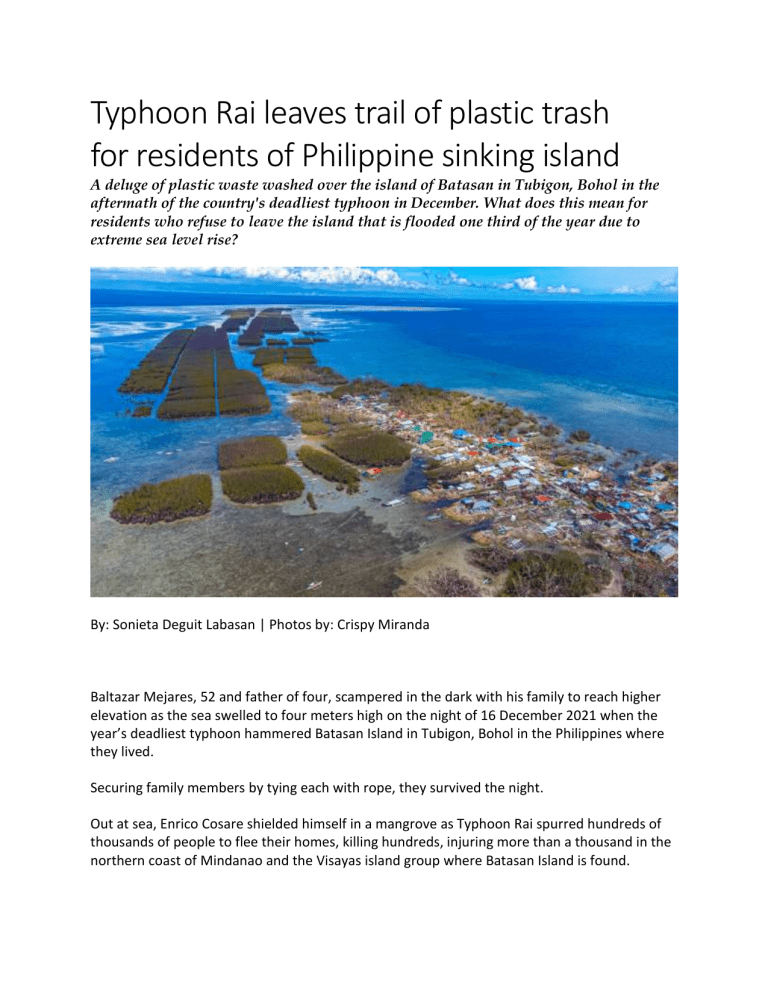

Typhoon Rai leaves trail of plastic trash for residents of Philippine sinking island A deluge of plastic waste washed over the island of Batasan in Tubigon, Bohol in the aftermath of the country's deadliest typhoon in December. What does this mean for residents who refuse to leave the island that is flooded one third of the year due to extreme sea level rise? By: Sonieta Deguit Labasan | Photos by: Crispy Miranda Baltazar Mejares, 52 and father of four, scampered in the dark with his family to reach higher elevation as the sea swelled to four meters high on the night of 16 December 2021 when the year’s deadliest typhoon hammered Batasan Island in Tubigon, Bohol in the Philippines where they lived. Securing family members by tying each with rope, they survived the night. Out at sea, Enrico Cosare shielded himself in a mangrove as Typhoon Rai spurred hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes, killing hundreds, injuring more than a thousand in the northern coast of Mindanao and the Visayas island group where Batasan Island is found. Cosare, a boatman who ferries passengers from the main province of Bohol to the island, considers the mangroves as the safest place for his boat during stormy weather with the trees as natural barriers against the waves and strong winds. At daybreak, however, he and fellow islanders were greeted with the sight of destruction and debris on the entire stretch of the 54-hectare mangrove where plastic bags, sachets, and sacks hung from the leafless branches. “Our mangroves are now like Christmas trees. By looking at the plastic bags stuck in it, you can tell how high the tide went that night,” said Cosare. A portion of the 54-hectare mangrove forest seems adorned with colored buntings from afar (left photo) but a closer view reveals plastic bags stuck in the trees (right photo). In the Batasan island proper, it was much worse with piles of trash washed into houses and even on the trees. Together with youth volunteers, the island’s barangay council has been spearheading clean-up operations every Sunday since 9 January. An elongated island resting on a shallow reef flat at the Cebu Strait, Batasan is one of Tubigon’s six island barangays and is about four miles from the Bohol mainland. Right after a 7.2 magnitude earthquake in 2013, the island subsided to about 1 metre. Rising sea levels worsened the problem, as scientists from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predict global mean sea levels to rise between one to three feet by the year 2100. “Based on my measurements as of 2016, Batasan is flooded 135 days in a year, partially or totally, depending on the tide level and local weather conditions. But every year, it has been observed that tidal flooding has become more frequent and takes longer for each flood event,” revealed Ma. Laurice Jamero, PhD, a contributing author to the IPCC Working Group I 6th Assessment Report. Despite experiencing tidal flooding due to land subsidence and global rising seas, residents refuse to relocate and had opted for local mitigating measures, such as building stilted houses, raising floors, elevating their belongings and appliances. Left photo shows clear sea waters invade the front yard of the Mijares’ residence during tidal flooding but after Typhoon Rai, the space was crammed with debris (right photo). The municipal government of Tubigon presented a relocation programme in response to the tidal flooding but only 70 out of the more than 300 families signed in. Batasan’s 871 inhabitants rely heavily on subsistence fishing in the area and prefer to stay in the island rather than venture into a new livelihood and an unfamiliar environment. “It is no surprise that many of them are reluctant to leave. Involuntary relocation may lead to greater vulnerability, due to loss of social capital and sense of identity. Attachment to place, which is closely linked to a sense of pride associated with belonging to a community, has also been shown to be a powerful determinant of the final decision to migrate,” said Jamero. A day before Rai, residents even opted to sign a waiver when the local government implemented a forced evacuation. The islanders underestimated the typhoon’s strength since Bohol was under Typhoon Signal No. 2 that day and the sea level in the evening was only 1.1 meters. Having weathered many storms in the past, the residents did not expect the rapid intensification of Rai, which battered their island leaving a trail of destruction for their houses and boats. A worker clears the ruins of the collapsed Gabaldon Building of Batasan Elementary School. The barangay’s covered court, health center, day care center and three public school buildings were totally destroyed as well as the new power generator that would have afforded 24-hour electricity to the island starting January, 2022. While there were no casualties, some residents needed medical attention but had to wait for two days before being transported to the mainland as all the boats were destroyed. After the experience that left her sleepless and shivering in the cold as all her clothes and belongings were washed away with her house, octogenarian Mamai Goc-ong is now eager to comply with the government's evacuation orders in the event of another strong typhoon. -END- CAPTIONS: With their houses and belongings washed away by the storm, 80-year-old Mamai Goc-ong (seated) with her brother Cristino and his wife Eleuteria, both 71, (standing) take refuge at a niece’s residence. The barangay’s covered court where residents used to congregate for community events was totally damaged. Adjacent to it is the school building (with green roof) that was used as an evacuation center but was also inundated during the storm; the evacuees escaped by making a hole through its roof. Plastic and waste materials washed into what remains of houses in Batasan. Two fisherfolks attempt to repair a fishing boat destroyed by the super typhoon. A child plays with an old tire in front of a fallen electric post at the island’s only street. Residents slowly pick up the pieces of their lives tattered by Typhoon Rai. Clearing the debris and waste materials that flood their island at the aftermath of Typhoon Rai has become an enormous challenge for the residents of Batasan Island. Enrico Cosare pulls his bandong, a local boat. At his back is the 54-hectare mangrove of Batasan Island. Baltazar Mejares (left), a member of the Barangay Council, with Batasan Punong Barangay Rodrigo Cosicol (right).