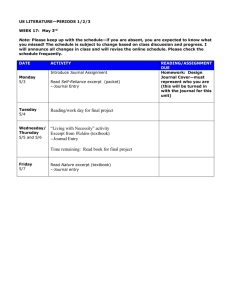

Education Higher education Local Education The Answer Sheet Jay Mathews These are books school systems don’t want you to read, and why By Laura Meckler and Perry Stein April 28, 2022 at 10:19 a.m. EDT In the memoir “Gender Queer,” readers see author Maia Kobabe struggling with questions about identity, sex and life; the author ultimately identifies as gender nonbinary and asexual. The kid version of “Stamped” shows how racism shaped the lives of five historical figures. “And Tango Makes Three” is the true story of two gay penguins that adopt an egg. All three books have been called inappropriate for children and have been subject to school library bans and turned into exhibits in the culture war. Critics say they are offensive and sometimes needlessly graphic. Defenders say the books paint truthful portraits — and help young people to see their place in the world. Either way, the United States is facing an unprecedented wave of schoolbook banning. PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for freedom of expression, tallied 1,586 book bans in schools over the past nine months, targeting 1,145 books. The American Library Association tracked 729 attempts to remove library, school and university materials last year, leading to 1,597 book challenges or removals. For comparison, the association counted challenges or bans of 273 books in 2020, 377 in 2019 and 483 in 2018. The debate has stretched from school board meetings to the halls of Congress. During Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Ketanji Brown Jackson, Sen. Ted Cruz (RTex.) read from Ibram X. Kendi’s books “Antiracist Baby” and “Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You.” Cruz insisted that Jackson explain why those books are available at the private school where Jackson serves on the board. The recent challenges fall into several categories. Some of the challenges involve books dealing with race, sexuality or gender and come from conservatives. But not conservatives alone. Liberals also have challenged classics such as “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “Huckleberry Finn,” saying they use racist language and character stereotypes. Recently, a Tennessee school district removed a book about the Holocaust. The Post counted 10 common rationales for book bans, alongside prominent examples of each. 1 Gender Queer, by Maia Kobabe What the book is about: This memoir, written in the form of a graphic novel, takes readers along author Maia Kobabe’s journey from adolescence into adulthood, navigating confusing questions about sexuality and gender identity. Ultimately, Kobabe comes out as gender nonbinary and asexual, adopting the gender-neutral pronouns e, em and eir. Throughout the story, Kobabe struggles with crushes, dating and figuring out who e is attracted to and why. E evolves from presenting as a girl to presenting as somewhere between the genders. Kobabe also faces painful moments connected to eir own body, such as menstruation and Pap smears. But the story ends in joy, with family and friends accepting Kobabe, as e finds happiness in eir own skin. Why critics object: The book, which has faced an enormous number of challenges, includes graphic sexual scenes depicting masturbation, a sex toy and oral sex, as well as depictions of menstrual blood and Kobabe’s fantasizing about having a penis. Critics note that the discussion and drawings about sex are not fleeting but are woven into the story, and they argue that the book is “pornographic.” One place it’s banned: Waukee (Iowa) Community School District, in 2021. Excerpt: “Why am I like this??? Sometimes I feel like my sexuality is broken and my gender is broken. I feel like there are all these wires in my brain which were supposed to connect body to gender identity and sexuality. But they’ve all been twisted into a huge snarled mess.” 0:00/1:14 Charlie Ballenger, grade eight, reads an excerpt from “Gender Queer.” 2 To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee What the book is about: The book, published in 1960, is set in a fictional Alabama town during the Great Depression. White attorney Atticus Finch defends a Black man who is falsely accused of raping a White woman. Finch faces down community pressure and a mob set on lynching his client. The story weaves the legal drama with the comingof-age story of Finch’s young daughter, Scout, who learns about acting with empathy and justice in a community beset by racism and prejudice. The novel won the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Last year, New York Times readers voted it best book of the past 125 years. Why critics object: Unlike other texts, this one is typically challenged from the left. Critics deride its use of racial slurs, including the n-word, as well as the centrality of a “White savior” character, Atticus Finch. They say that Finch tolerates much racism in the community and that, in general, the novel depicts a world in which racism is the norm. One place it’s banned: Burbank (Calif.) Unified School District, in 2020. Excerpt: “Why reasonable people go stark raving mad when anything involving a Negro comes up, is something I don’t pretend to understand. ... I just hope that Jem and Scout come to me for their answers instead of listening to the town. I hope they trust me enough.” 0:00/0:45 Finnian Barrett, grade seven, reads an excerpt from “To Kill A Mockingbird.” 3 New Kid, by Jerry Craft What the book is about: This graphic novel follows 12-year-old Jordan Banks, an African American from Washington Heights in Manhattan, as he begins seventh grade at the prestigious and wealthy Riverdale Academy Day School, navigating the typical anxieties of middle school on top of the extra pressure of being one of the few students of color. Teachers mix up one Black student with another, stereotypes run rampant and students on financial aid are sometimes identified as such. His new classmates take luxury vacations and label pink shorts “salmon.” Meanwhile, at home in his Black and Hispanic neighborhood, Jordan tries to stay connected to his roots. Why critics object: A petition last fall signed by some 400 parents alleged that the book was “wrought with critical race theory,” which holds that systemic racism is woven into this country’s institutions. The critics alleged that the book teaches children that White privilege comes with microaggressions that should be kept in check. The objections prompted a school district temporarily to pull “New Kid” from school libraries and to cancel an event with the author. The online event was later rescheduled. One place it’s been challenged: Katy (Tex.) Independent School District, in 2021. Excerpt: In illustrated speech bubbles, Jordan talks with Drew, one of the few other Black students at Riverdale. Drew: I’ve been here two months and people still don’t really talk to me. Jordan: But you’re one of the stars of the football team. Drew: I get lots of high fives and “good game, Bro.” But it doesn’t really go past that. ... So what’s up with Ms. Rawle always calling me DEANDRE? Jordan: I know, right? Some kids even called me Maury a few times. Drew: See? Those are the things that bother me. Like whenever a class talks about slavery or civil rights-Jordan: Everyone stares at you, right? And financial aid! 0:00/0:56 Isaiah Holman, grade ten, reads an excerpt from “New Kid.” 4 Maus, by Art Spiegelman What the book is about: This black-and-white graphic novel gives a raw, unsparing depiction of the Holocaust. Nazi oppressors are rendered as cats; their victims are mice. The story details atrocities committed during Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, including the killing of infants, and the use of gas chambers and forced labor. It is based on the experience of the author’s parents during the Holocaust. Why critics object: In January, a Tennessee school district banned use of the text in middle school classes. Officials cited profanity, nudity (of cartoon animals) and depiction of violence and suicide. One school board member pointed to scenes in which a father talks with his son about losing his virginity and where a woman cuts herself with a blade. One place it’s banned: McMinn County (Tenn.) Schools, in 2022. Excerpt: Mouse: “That spring, on one day, the Germans took from Srodula to Auschwitz over 1,000 people.” Narrator: Most they took were kids — some only 2 or 3 years. Some kids were screaming and screaming. They couldn’t stop. So the Germans swinged them by the legs against a wall ... And they never anymore screamed. 0:00/1:56 Gabriel Perla, grade eleven, reads an excerpt from “MAUS.” 5 The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, by Nik l H hJ d h N Y k Nikole Hannah-Jones and the New York Times Magazine What the book is about: “The 1619 Project,” first a special issue of the New York Times Magazine and then a book, posits that 1619, the year enslaved Africans first arrived in what would become the United States, might be considered the founding of the nation, not the commonly celebrated 1776. The project seeks to “reframe American history, making explicit that slavery is the foundation on which this country is built.” It includes an opening essay by Hannah-Jones looking at American history from a Black perspective and examining her own place in the American story. Subsequent chapters explore American life through the lens of the Black experience including guns, capitalism, criminal justice, inheritance and culture. Why critics object: Conservatives, including former president Donald Trump, say it paints an overly negative view of American history. The project also has been criticized by some historians for certain factual errors, such as an assertion that protecting the institution of slavery was a prime motivator for the colonists who declared independence from Britain. Places it’s banned: All schools in Florida and Texas. Excerpt: The United States is a nation founded on both an ideal and a lie. Our Declaration of Independence, approved on July 4, 1776, proclaims that “all men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.” But the white men who drafted those words did not believe them to be true for the hundreds of thousands of Black people in their midst. A right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” did not include fully one-fifth of the new country. Yet despite being violently denied the freedom and justice promised to all, Black Americans believed fervently in the American creed. Through centuries of Black resistance and protest, we have helped the country live up to its founding ideals. 0:00/1:11 Marley Sowah, grade eleven, reads an excerpt from “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story.” 6 And Tango Makes Three, by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell What the book is about: This children’s book tells the true story of Roy and Silo, two male penguins at the Central Park Zoo in Manhattan who paired as a couple. The penguins sing to each another, wind their necks around one another and sleep together on a nest of stones. Silo and Roy can’t produce an egg, so they take turns sitting on a rock. A zookeeper, noticing this, brings them an egg that needs to be care for, and Roy and Silo take turns sitting on it until they hatch a baby penguin, Tango. Tango’s daddies teach her to swim, play with her and cuddle with their baby at night. Why critics object: They say the story is anti-family, promotes homosexuality and is unsuitable for young readers. The book has been regularly challenged over more than a decade. One place where it’s been challenged: Independence, Kan., Public Library, 2020. Excerpt: Roy and Silo were both boys. But they did everything together. They bowed to each other. And walked together. They sang to each other. And swam together. Wherever Roy went, Silo went too. They didn’t spend much time with the girl penguins, and the girl penguins didn’t spend much time with them. Instead, Roy and Silo wound their necks around each other. Their keeper Mr. Gramzay noticed the two penguins and thought to himself, “They must be in love.” 0:00/1:05 Jack Simon Robbins, grade five, reads an excerpt from “And Tango Makes Three.” 7 Out of Darkness, by Ashley Hope Pérez What the book is about: Set in the 1930s in a small but wealthy Texas town, this historical, young adult novel follows the love story of a Mexican American girl and an African American boy who connect over their experiences of racism. The story unfolds against the backdrop of the 1937 New London, Tex., school explosion — one of the deadliest school tragedies in American history. It killed nearly 300 students and teachers. Why critics object: Parents have called for the book to be banned because of what they describe as pornographic depictions of sex, with a particular focus on one scene that refers to anal sex. A video of a Texas mother lambasting the book at a school board meeting went viral last year as she described why she found the scene so offensive: “I do not want my children to learn about anal sex in middle school,” she said. “I’ve never had anal sex. I don’t want to have anal sex. I don’t want my kids having anal sex.” The school district later pulled the book from its shelves. Responding to the criticism, the author said the scene was taken out of context and is from the viewpoint of racist boys who are objectifying the main character. One place it’s been challenged: School District of Osceola County (Fla.), in 2022. Excerpt: “Looking for the cigar factory?” Miranda said when the Mexican girl walked past her on the way to the one empty seat at the front of the room. Miranda raised her eyebrows at Vanessa and Gladys and Betty Lee. They laughed. Some of us joined in. Most of us couldn’t see the Mexican girl’s face from where we sat. Still, we wondered could Mexicans blush? 8 Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You, by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi What the book is about: This is the middle school version of American historian and activist Ibram X. Kendi’s adult book “Stamped from the Beginning.” The adaptation is written with the young adult author Jason Reynolds and is a fast-paced read that examines the history of racism and anti-racism by showing how prejudice shaped the lives of five historical figures. The book chronicles how racism manifests itself in modern society and introduces readers to anti-racists, people who believe that there is nothing “wrong or right about black people and everything wrong about racism.” Why critics object: Critics claim that the book contains “selective storytelling incidents” and does not include context about racism against all people, according to the American Library Association, which included the title on its list of most-challenged books of 2020. They also take issue with public comments made by Kendi, a prominent activist known for speaking out against discriminatory policies. One place where it’s been challenged: Berlin (N.J.) Borough School District, 2021. Excerpt: When I was in school and first really learning about racism, I was taught the popular origin story. I was taught that ignorant and hateful people had produced racist ideas, and that these racist people had instituted racist policies. But when I learned the motives behind the production of racist ideas, it became obvious that this folktale, though sensible, was not true. I found that the need of powerful people to defend racist policies that benefited them led them to produce racist ideas, and when unsuspecting people consumed these racist ideas, they became ignorant and hateful. 0:00/1:52 Zamir Walls, grade eight, reads an excerpt from “Stamped (For Kids): Racism, Antiracism, and You.” 9 The Bluest Eye, by Toni Morrison What the book is about: Published in 1970, this is the first novel by Nobel Prizewinning author Toni Morrison. It tells the story of a young African American girl, Pecola, in Ohio who grows up in poverty with abusive and unstable parents. Her escape is to dream about having blue eyes, believing that would make her more beautiful and loved in the world. The story, narrated by Black girls, shows how Pecola views herself in the world and how the world sees her. Why critics object: School districts across the country have tried to ban this book for decades. They have cited crude language and graphic depictions of rape and sex. One place it’s been banned: Colton (Calif.) Joint Unified School District, in 2020. Excerpt: Pecola lost her balance and was about to careen to the floor. Cholly raised his other hand to her hips to save her from falling. He put his head down and nibbled at the back of her leg. His mouth trembled at the firm sweetness of the flesh. He closed his eyes, letting his fingers dig into her waist. The rigidness of her shocked body, the silence of her stunned throat, was better than Pauline’s easy laughter had been. The confused mixture of his memories of Pauline and the doing of a wild and forbidden thing excited him, and a bolt of desire ran down his genitals, giving it length, and softening the lips of his anus. 0:00/2:04 Lacaya Granberry, grade eleven, reads an excerpt from “The Bluest Eye.” 10 It’s Perfectly Normal, by Robie H. Harris and Michael Emberley What the book is about: This popular sex education book teaches children 10 and older about their changing bodies, sex and gender identity. It has sections about sexual and emotional relationships, sexual orientation and pregnancy. It explains to readers that sex can be for pleasure or for reproduction, and it can be between people of different genders or the same gender. The book contains nude cartoons of people throughout, depicting adults having sex. An updated version of the book contains information for transgender youths. Why critics object: They say the book is too graphic and sexually explicit for children. In 2019, Arizona Republican state Rep. Kelly Townsend unsuccessfully called on schools systems and libraries to remove the books from their shelves, citing its “drawn depictions of teenagers engaged in sexual intercourse.” One place it’s been banned: Rainier (Ore.) School District, in 2017. Excerpt: Sexual intercourse, or as it is often called, “making love,” is a kind of sharing between two people — between a female and a male, or between two females, or between two males. Touching, caressing, kissing, and hugging — often called “making out” — are other kinds of sharing that can make two people feel very close and loving and excited about each other. People can and do become sexually excited without having sexual intercourse. Editing by Adam Kushner. Photo editing by Mark Miller. Audio editing by Rennie Svirnovsky. Copy editing by Gilbert Dunkley. Design by Julia Terbrock.