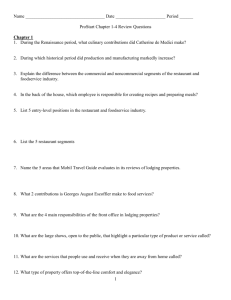

FOUNDATIONS of Restaurant Management & Culinary Arts Level One ( PDFDrive )

advertisement