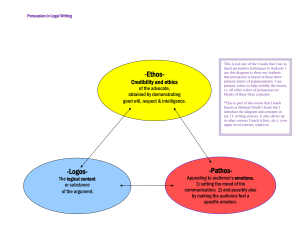

TECHNIQUES AND TACTICS OF PERSUASION Many people interchangeably use techniques and tactics. Although it is quite confusing, a clear distinction can be drawn out from the point that techniques are usually the skills and methods meant for achieving long term strategic goals whiles tactics are approaches meant for achieving short term objectives. Therefore, techniques and tactics of persuasion refers to the skills, methods and approaches used by one party to influence the other in negotiation. In a broader sense, persuasion is an aspect of negotiation. With respect to this, negotiation can be defined as a process of planning, reviewing and analyzing used by both a supplier and a customer on the overall cycle of a product not only pertaining to the price. We are confronted by persuasion in a wide variety of forms every single day. Persuasion is not just something that is useful to marketers and salesmen. However, learning how to utilize these techniques and tactics in daily life can help you become a better negotiator and make it more likely that you will get what you want. Because influence is so useful in so many aspects of daily life, persuasion techniques have been studied and observed since ancient times. It wasn’t until the early 20th-century, however, that social psychologists began formally study these powerful techniques. Persuasion is an umbrella term of influence. Persuasion can attempt to influence a person's beliefs, attitudes, intentions, motivations, or behaviors. According to Perloff (2003), persuasion can be defined as "...a symbolic process in which communicators try to convince other people to change their attitudes or behaviors regarding an issue through the transmission of a message in an atmosphere of free choice." TACTICS FOR NEGOTIATION Definition: Negotiation tactics are the detailed methods employed by negotiators to gain an advantage over other parties. Tactics are often deceptive and manipulative and are used to fulfil one party's goals and objectives - often to the detriment of the other negotiation parties. This makes most tactics in use today 'win-lose' by nature. We would like to urge negotiators to only use ethical tactics. We are against using most tactics in principle, and recommend instead that you seek a more collaborative, open and trust building approach wherever possible. It is however worth learning how to identify and defend against tactics. We have so many tactics in negotiation but below are some few of them 1. Know your context. Is the negotiation one-shot or long-term? In "The Mind and the Heart of the Negotiator," Kellogg management professor Leigh Thompson notes that the interaction between a customer and the wait staff at a highway roadside diner is one of the few one-shot negotiations that happen in life — there's little chance that patron or staff will see each other again. But every other negotiation is long-term, with employment negotiations as a primary example. If it's long-term, you need to manage not only monetary value, but the impression you're making. 2. Make the first offer. It makes use of the anchoring effect. If you start high, the hiring manager may adjust the figure down slightly. But that's typically a stronger position than starting low and trying to negotiate up. "Whoever makes the first offer essentially drops an anchor on the table," Thompson tells Business Insider. "I might say that your opening offer is ridiculous, but nevertheless, unconsciously, I've been anchored." 3. Make an aggressive offer. Columbia University negotiation scholar Adam Galinsky says that people are overly cautious when making first offers. On HBS Working Knowledge, Galinsky likens negotiating a salary to selling a house: Take the perspective of the seller: more extreme first offers lead to higher final settlements. High-anchor offers lead buyers to focus on a negotiated item's positive attributes. In addition, an aggressive first offer allows you to offer concessions and still reach an agreement that's much better than your alternatives. In contrast, a nonaggressive first offer leaves you with two unappealing options: Make small concessions or stand by your demands. 4. Before you go in, know the lowest amount you'd accept. Scholars call it the "reservation value," or the lowest amount you'll take. "We always hope to do better than our reservation values," writes negotiation expert Chad Ellis, "but it's important to know what yours is, both to avoid accepting a deal you shouldn't have and as a reference point for how much a current deal is worth to you." Having a firm grasp of your reservation value is important from a psychological perspective: If you anchor it into your mind, you'll be less anchored by the other person's offer. 5. Mirror the other person's behavior. When people are getting along, they mimic one another — mirroring each other's accents, speech patterns, facial expressions, and body language. A Stanford-Northwestern-INSEAD study found that people who were coached to mimic their negotiation partners behavior not only negotiated a better deal, but expanded the pie for both people. "Negotiators who mimicked the mannerisms of their opponents both secured better individual outcomes, and their dyads as a whole also performed better when mimicking occurred compared to when it did not". 6. Emphasize your potential. A Stanford-Harvard study recently cited on Marginal Revolution suggests that accomplishments aren't what capture people's attention — rather, it's a person's perceived potential. "This uncertainty [that comes with potential] appears to be more cognitively engaging than reflecting on what is already known to be true." 7. Don't demand a single number. New research indicates that people respond best when given a "bolstering range offer," where you state the number that you're looking for — and a range above it. If you're trying to get to a $100,000 salary, ask for $100,000 to $120,000. Offering a range strikes people as more reasonable than standing firm on a single number, so you're less likely to get hit with an extreme counteroffer, which suddenly become way less polite. 8. Tell them something about yourself. In a 2002 experiment cited by Adam Grant, Northwestern and Stanford students were asked to negotiate over email. Some went straight to business, exchanging only names and email addresses. Others went off-topic, "schmoozing" about hometowns and hobbies. The schmoozers reached an agreement 59% of the time, while the business-only made it 40% of the time. 9. Keep all your options on the table. Skilled negotiators don't "sequence" the topics within a negotiation. They keep everything on the table. So instead of saying "Let's resolve the salary first, and then we'll move on to the other issues," you resolve the components of the agreement all together; location, vacation time, or signing bonus. "By keeping all of the issues on the table, you have the flexibility to propose trading location and bonus for a bump in salary." Aside this 9 tactics for negotiation, there are other tactics that can influence you to say yes during negotiation. These are; Consistency – The first of the influence tactics demonstrates that we normally follow consistency, so if someone commits on a small level to something, they are more likely to be consistent and continue committing to it later. An example in the sales world is to ‘try before you buy’. The chance of purchasing after this are greater than purchasing ‘cold’. Reciprocation – As humans, we generally aim to return favours and pay back people that have given us something. By offering something to someone can help them feel obliged to return the favour and compelled to ‘comply’. Again, in the sales world, this could be a free gift added in. Social proof – We are influenced by other ‘similar’ people. If a team works late, then maybe we will too in order to comply. Again, if a group of people are doing something, then there is a greater chance that others will inherently follow through this peer following. The social proof influence tactic gently persuades our sub conscious that if other people are doing something, so should we. Authority – We feel a sense of obligation and duty to people who are seen as being authoritative in their positions. A great example would be that of advertisers of pharmaceutical products: often a doctor is seen promoting their products to help drive a level of authority. We don’t normally argue against experts in their fields! Liking – We are more likely to be influenced by other people we like. Likeability comes in different ways: people may be familiar to us or share similar views and opinions. Likeability may also come in the form of trust, but either way, we are influenced by those we are affiliated to. Scarcity – This influence tactics is seen a lot in advertising. Often, we hear, ‘’for a limited time only,’’ or, ‘’only xx left!’’ it is with the principle that people need to know what they are potentially missing out on if they fail to act. By providing the scarcity rule, the chances of more people responding are increased. HOW TO USE THESE INFLUENCE TACTICS You can use these principles and influence tactics whenever you want to persuade other people to comply with a certain behaviour. Just remember, successful leaders do not manipulate and deceitfully gain advantage. They are open and people-driven leaders, so use the tool fairly and morally. 1. Start with the end in mind – know your objectives and what you are trying to get out of the situation. 2. Understand your team members that you are trying to influence and select the correct influence tactics that would suit the situation. 3. Use the strategies to suit. Here are few examples of how to use each influence tactic: Consistency / commitment – Try to get their commitment early into the project or conversation. Try too, to get them to commit to something small. There is more chance of them progressing and developing their commitment once they have already contributed something to it. Also, try to get someone to commit to something preferably in writing, perhaps in the form of a SMART objective, or a signing of a project charter, or an agreement to be a part of an improvement project. This provides more of an anchor towards future commitment. Reciprocity – Think about your objectives again and identify how you can give something to the person/s involved. It may even be just a gentle reminder of how you have helped in the past. Try to demonstrate ways to show a little give and that the person/s are benefiting from it. By providing the sense that you have ‘scratched their backs’, they are more inclined to oblige to do something in return. Liking – Be natural and fair; be open and honest in your actions and have a general interest in people and their welfare. This forms the bases of good leadership and will also begin to build trust, which is one of the branches of liking and respect. Authority – Fined ways to show others of your expertise, so everyone can understand your strengths and knowledge. Scarcity – If you are selling a product, ensure you give the customer a limited time available, in order to buy, or limit the stock, and so on and so forth. The trick here is to demonstrate a clear limitation and also what would happen if you do not ‘comply’ or act. In terms of influencing people within a team setting, the creation of urgency is key. Social Proof – focus on finding the right people and then communicating this message to show support in the programme. If you master the art of communication and indeed successful influence tactics, your whole world as a leader can be enhanced. It can be an extremely effective and rewarding experience to influence those around you to act. To be able to tap into the psyche of the human mind using a range of influence tactics and to persuade people in a positive fair and moral way, will have a profound impact on your role as a leader. Persuasion Techniques The ultimate goal of persuasion is to convince the target to internalize the persuasive argument and adopt this new attitude as a part of their core belief system. The following are just a few of highly effective persuasion techniques. Other methods include the use of rewards, punishments, positive or negative expertise, and many others. 1. Create a Need One method of persuasion involves creating a need or an appealing a previously exiting need. This type of persuasion appeals to a person's fundamental needs for shelter, love, self-esteem and self-actualization. Marketers often use this strategy to sell their products. Consider, for example, how many advertisements suggest that people need to purchase a particular product in order to be happy, safe, loved, or admired. 2. Appeal to Social Needs Another very effective persuasive method appeals to the need to be popular, prestigious or similar to others. Television commercials provide many example of this type of persuasion, where viewers are encouraged to purchase items so they can be like everyone else or be like a well-known or well-respected person. Television advertisements are a huge source of exposure to persuasion considering that some estimates claim that the average American watches between 1,500 to 2,000 hours of television every year. 3. Use Loaded Words and Images Persuasion also often makes use of loaded words and images. Advertisers are well aware of the power of positive words, which is why so many advertisers utilize phrases such as "New and Improved" or "All Natural." 4. Get Your Foot in the Door Another approach that is often effective in getting people to comply with a request is known as the "foot-in-the-door" technique. This persuasion strategy involves getting a person to agree to a small request, like asking them to purchase a small item, followed by making a much larger request. By getting the person to agree to the small initial favor, the requester already has their "foot in the door," making the individual more likely to comply with the larger request. For example, a neighbor asks you to babysit her two children for an hour or two. Once you agree to the smaller request, she then asks if you can just babysit the kids for the rest of the day. Since you have already agreed to the smaller request, you might feel a sense of obligation to also agree to the larger request. This is a great example of what psychologists refer to as the rule of commitment, and marketers often use this strategy to encourage consumers to buy products and services. 5. Go Big and Then Small This approach is the opposite of the foot-in-the-door approach. A salesperson will begin by making a large, often unrealistic request. The individual responds by refusing, figuratively slamming the door on the sale. The salesperson responds by making a much smaller request, with often comes off as conciliatory. People often feel obligated to respond to these offers. Since they refused that initial request, people often feel compelled to help the salesperson by accepting the smaller request. 6. Utilize the Power of Reciprocity When people do you a favor, you probably feel an almost overwhelming obligation to return the favor in kind. This is known as the norm of reciprocity, a social obligation to do something for someone else because they first did something for you. Marketers might utilize this tendency by making it seem like they are doing you a kindness, such as including "extras" or discounts, which then compels people to accept the offer and make a purchase. 7. Create an Anchor Point for Your Negotiations The anchoring bias is a subtle cognitive bias that can have a powerful influence on negotiations and decisions. When trying to arrive at a decision, the first offer has the tendency to become an anchoring point for all future negotiations. So if you are trying to negotiate a pay increase, being the first person to suggest a number, especially if that number is a bit high, can help influence the future negotiations in your favor. That first number will become the starting point. While you might not get that amount, starting high might lead to a higher offer from your employer. 8. Limit Your Availability Psychologist Robert Cialdini is famous for the six principles of influence that he first outlined in his best-selling 1984 book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. One of the key principles he identified is known as scarcity, or limiting the availability of something. Cialdini suggests that things become more attractive when they are scarce or limited. People are more likely to buy something if they learn that it is the last one or that the sale will be ending soon. An artist, for example, might only make a limited run of a particular print. Since there are only a few prints available for sale, people might be more likely to make a purchase before they are gone. 9. Spend Time Noticing Persuasive Messages The examples above are just a few of the many persuasion techniques described by social psychologists. Look for examples of persuasion in your daily experience. An interesting experiment is to view a half-hour of a random television program and note every instance of persuasive advertising. You might be surprised by the sheer amount of persuasive techniques used in such a brief period of time. Psychology of Concession Negotiation concession are also sometimes referred to as ‘trade-offs’ where one or more parties to a negotiation engage in conceding, yielding, or compromising on issue under negotiation and do so either willingly or unwillingly. These are some Four Strategies for Making Concessions Concessions are often necessary in negotiation, most people understand that negotiation is a matter of give-and-take: You have to be willing to make concessions to get concessions in return. But the process of making concessions is easier said than done. The four strategies are as follows 1. Label your concessions In negotiation, don't assume that your actions will speak for themselves. Your counterparts will be motivated to overlook, ignore, or downplay your concessions. Why? To avoid the strong social obligation to reciprocate. As a result, it is your responsibility to label your concessions and make them salient to the other party. When it comes to labeling, there are a few rules to follow. First, let it be known that what you have given up (or what you have stopped demanding) is costly to you. By doing so, you clarify that a concession was, in fact, made. Second, don't give up on your original demands too hastily. If the other side considers your first offer to be frivolous, your willingness to move away from it will not be seen as concessionary behavior. By contrast, your concessions will be more powerful when your counterpart views your initial demands as serious and reasonable. Accordingly, spend time legitimating your original offer and then use it as a reference point when labeling your concession. 2. Demand and define reciprocity Labeling your concessions helps trigger an obligation to reciprocate, but sometimes your counterpart will be slow to act on that obligation. To increase the likelihood that you get something in return for your concession, try to explicitly—but diplomatically—demand reciprocity. For example, consider the following negotiation between an IT services firm and a client. The client suggests that the IT firm's cost estimates are unreasonably high; the IT firm's project manager believes that the cost estimates are accurate (and perhaps conservative) given the complexity of the project and the short deadline. If the project manager is willing to make a concession, she might say: "This isn't easy for us, but we've made some adjustments on price to accommodate your concerns. We expect that you are now in a better position to make some changes to the project deadlines. An extra month for each milestone would help us immeasurably." Notice that this statement achieves three goals. First, it labels the concession ("This isn't easy for us, but we've made some adjustments ..."). Second, it tactfully demands reciprocity ("We expect that you are now in a better position to make some changes ..."). Third, it also begins to define the precise form that reciprocity should take ("An extra month for each milestone... "). While each of these elements is critical, negotiators often overlook the need to define reciprocity. Remember that no one understands what you value better than you do. If you don't speak up, you're going to get what your counterpart thinks you value or, worse, what is most convenient for your counterpart to give. 3. Make contingent concessions One hallmark of a good working relationship is that parties don’t nickel and dime each other for concession. Rather, each side learns about the interest and concerns of the other and makes good faith effort toward achieving joint gains. Unfortunately, while fostering such norms is desirable, it is not always possible. Engaging in mutual give and take during negotiations, one might have trouble doing so with suppliers or customers. This is because some are untrustworthy or entirely self-interested and are likely to exploit good will by refusing to reciprocate at all, much less in the way the concession has being defined. It is an advice that when trust is low or when one is engaged in a one- shot negotiation, contingent concession should be considered. A concession is contingent when you state that you can make it only if the other party agrees to make a specified concession in return. Contingent concessions are almost risk free. They allow you to signal that while you have room to make concession, it may be impossible for you to badge if reciprocity is not guarantee. Keep in mind however, that an over reliance on contingent concessions can interfere with building plans. If u demand immediate compensation every time you make a concession, your behavior will be seen as self-serving rather than oriented towards achieving mutual satisfaction. 4. Make Concessions in Installment Installment may lead you to discover that you don’t have to make as large as concession as you thought. When you give away a little at a time, you might get everything you want in return before losing your concession making capacity. Whatever is left over is yours to keep or to use to induce further reciprocity. Making small concession tells the other party that you are flexible and willing to listen to his needs. Each time you make a concession, you have the opportunity to label it and extract good will in return. REFERENCE; Media Dynamics. (2007). Our rising ad dosage: It's not as oppressive as some think. Media Matters. Retrieved from https://www.mediadynamicsinc.com/UserFiles/File/MM_Archives/Media%20Matters%2021507 .pdf 19th February 2016, 2:30pm Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-win-negotiations-2015-3?op=1 21st February 2016, 10:40am Robert B. C., J. E., V., S. K. L., J C., D. W., and B. L. D. (1975) Reciprocal Concessions Procedure for Inducing Compliance: The Door-in-the-Face Technique ,Journal oj Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 31, No. 2, 206-215, Arizona State University