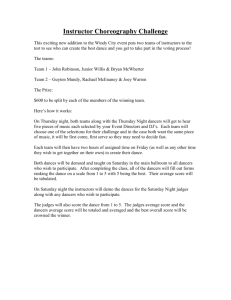

Onward and Upward with the Arts July 1, 2019 Issue Can Modern Dance Be Preserved? In safeguarding the legacies of innovators like Merce Cunningham and Paul Taylor, we risk losing their spirit. By Joan Acocella J019 The deaths of leading choreographers have made preservation an urgent concern. Illustration by Cristiana Couceiro. Photographs: Barbara Morgan / Getty (left); Jack Mitchell / Getty (center and right) There may be no one in the arts with a harder job than that of a moderndance choreographer. When a writer can’t figure out what to say next, she can turn off the computer and go take a nap. A choreographer, by contrast, is working not with a computer but with, say, ten or fifteen human dancers, who, if she finds herself stumped, will stand there and stare at her—and maybe, when she’s not looking, roll their eyes at one another—until she gets the rehearsal moving again. Which she’d better do, fast. To keep the company in business, with the bookings secured (typically, a year in advance) and the tickets selling, she needs to come up with at least one new work per year, plus, ideally, an important revival. Modern-dance companies are small, intense, personal. If Martha Graham felt that her dancers weren’t getting a passage right, she didn’t mind ripping the phone off the wall and throwing it on the floor. If she couldn’t think of what to do next, she might well run out of the studio and lock herself in her dressing room. Her staff would plead with her through the door. “Come out, Martha,” they would say. “It’ll be all right.” In the company’s early years, the dancers were paid almost nothing, and, reportedly, that was O.K. by them. According to one member of the novice group, they wouldn’t have defiled their service to Graham with thoughts of money. If this sounds diva-ish and crazy, there were nevertheless reasons for it. Modern-dance companies are almost always the creation of one person, and they are his or (frequently) her cri de coeur. She is the company. She is not just the primary—in most cases, the only—choreographer but also, ordinarily, the primary soloist. (This is not the case in ballet, where artistic directors are usually past their dancing years.) Everything comes from the founder: the training, the vision, the company’s distinctive movement style and technique. Because of this, the understanding in modern dance, for a long time, was that no one could ever take the boss’s place. In the earliest days—the days of Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, and then, in the next generation, Charles Weidman, Doris Humphrey, and others—the system was pretty ironclad. When the founder got old or fat or tired, she usually just went home, and the dancers moved on to other companies or got married or whatever. It was sad, but people were more stoical in those times, and more romantic about dance. They expected it to be short-lived. Even now, you often hear about how dance is “ephemeral”—the butterfly of one summer, the flower of an hour. If I am not mistaken, that elegiac note is often accompanied by a certain condescension: If a bunch of Bennington coeds and homosexuals have to give up and go get real jobs, tant pis! Lately, however, the question of what happens after the founder is gone has become urgent. A lot of modern-dance companies are talking about “legacy” and trying to come up with ways to perpetuate it. Why? Well, the art form is more than a century old. Many modern-dance companies are now big institutions, prestigious features of our cultural landscape. If they disband, a ton of people will lose their jobs. More important, there will no longer be anyone to perform the dances properly, in the style passed down through generations of dancers. The work will cease to exist. It would be as if, when Rembrandt died, all his canvases were taken out into the back yard and burned. The longevity of some of the leading figures in American modern dance may have delayed a reckoning with the legacy issue. Merce Cunningham died in 2009, at the age of ninety; Paul Taylor last year, at eighty-eight. Martha Graham, who died in 1991, lived to ninety-six, and had gone on choreographing well into her nineties. (She was still dancing into her seventies.) But, as such artists approached the end, the question “What’s next?,” hitherto politely unspoken, became impossible to ignore. Five years ago, Taylor told Michael Cooper, of the Times, that he thought his board of directors was wondering what was going to happen “if the time comes that I can’t crank out something.” And, unsurprisingly, cranking out something was what, for the most part, he was doing at that point. When he came out to take a bow at a première, he often looked as though he were dying already. Ditto Graham: for curtain calls, she sometimes had to be carried out in a chair and placed onstage before the curtain was opened. What champs they were! And how false it all was: a pageant of continuance in flat denial of imminent crisis. The fortunes of Graham’s company produced an early warning of how wrong things can go in the posthumous life of a dance troupe. As her heir, Graham anointed Ron Protas, a man more than forty years younger than she, who’d become her boon companion in her later life. Protas was not a choreographer, not even a dancer, and the company was soon mired in disagreements with him. But how could it remove him? He laid claim to Graham’s choreographies and even her famous technique. It took six years for the courts to pry the dances, or most of them, out of his hands and turn them back over to the troupe. A common problem in long-lived modern-dance troupes is “olderdancer syndrome.” A number of the people in the company may have been there for twenty years or more, in which case they will probably be used to taking orders from only one person. If that person is gone, most of them do not happily follow instructions from someone new. They perform the steps the way they think they should, and declare that this is the right way, when in fact it may be the product of a thousand little adjustments they have made over the years as their bones got older and their original boss more indulgent. If the replacement boss, in desperation, then hires some new people, people willing to listen to her, the elders will dislike her all the more. In 2009, Pina Bausch, the longtime director of the Tanztheater Wuppertal, in Germany, died suddenly, of cancer, at the age of sixtyeight, leaving no instructions about how her company should proceed without her. Bausch had a famously individual style, very theatrical (cliffs of dirt, collapsing walls) but also, in her dancers’ physical dealings with one another, very intimate—visceral, sticky, a little disgusting, but excitingly so. No one wanted to buy tickets to a schoolof-Bausch show, but neither did audiences want to see non-Bausch works programmed alongside hers. And the Bausch company had olderdancer syndrome in spades. Still today, more than half the troupe’s thirty-four dancers are over forty, and four of them are over sixty. Therefore it was no surprise that in less than ten years after Bausch’s death the troupe went through four would-be artistic directors, the last of whom—Adolphe Binder, dismissed after little more than a year—sued the company on her way out. In an announcement, she wrote, “My work was constantly hindered, information on the budget and cooperation were denied to me, and I was personally defamed and degraded.” The troupe’s executive director, Dirk Hesse, who had worked at the Tanztheater for thirty years, also resigned. Think what that means: thirty years of knowledge about how to run this complicated organization, and out the door it goes. The company struggled forward without a director for four months. Then, in January of this year, the Tanztheater hired Bettina WagnerBergelt, who for sixteen years was the deputy director of the Bavarian State Ballet, in Munich. Her job is not to create new dance-theatre pieces, as Bausch did, but to commission them from others and get them onstage. With her comes a new executive director, Roger Christmann, as an equal partner. They have a contract of two and a half years, and Wagner-Bergelt thinks that this is enough time to allow her to meet her goal of assembling an up-to-date repertory that nevertheless stresses Bausch’s work above all. As the years pass, though, this goal is going to be increasingly hard to meet. Bausch being dead, her work will eventually cease to be au courant. Already the schedule suggests a slightly frantic rummage deep in her closet. The big Bausch work for the 2019-20 season will be a restaging of her “Bluebeard. While Listening to a Tape Recording of Béla Bartók’s Opera ‘Duke Bluebeard’s Castle,’ ” which had its première in 1977 and hasn’t been seen outside Germany since the mid-eighties. That is, it is old enough to seem new. Merce Cunningham, though he performed almost as long as he could stand upright, took the opposite of the survivalist approach. He left instructions that after his death his troupe, almost sixty years old, should tour for two years and then disband. This was a monumental decision, a reflection, many people felt, of Cunningham’s unflinching character. On the night of the troupe’s last performance, December 31, 2011, three stages were set up in the Park Avenue Armory’s vast drill hall, each with a Cunningham dance taking place on it. For close to an hour, you walked from space to space in the hall, watching these grave-faced people doing decades’ worth of Cunningham choreography, as great clusters of white balloons floated above their heads—a cross between Tiepolo and Andy Warhol. “They’re going to Heaven,” you said to yourself, “where Cunningham went. And so will I, and so will all of us. This is terrific.” But it wasn’t. The next day, we woke up in a world that no longer ushered spring into New York, every year, with a Cunningham season. The longtime dance archivist Norton Owen says that Cunningham’s choice was a product not just of artistic fortitude but, above all, of financial circumstances: “It was a decision made out of harsh reality. ‘I don’t see how it will go on, so I’ll just pull the plug.’ ” It’s not as though Cunningham had no thought for the future. For years, he had now and then let his people teach his work to other companies. In 2008, though, he hired an actual director of licensing—Patricia Lent, who had performed with the troupe in the eighties and nineties—and the business of passing the torch came to the forefront. More and more companies started calling, with requests ranging from the specific (“Can we have ‘Sounddance’ for two years?”) to the vague (“Can you suggest something we could do?”). Lent told me that, after she and the other company figure out which piece will be licensed, there’s a workshop to teach the choreography to the new dancers: “We try to teach it the same way we learned it. We clap, we count, we sing the rhythms.” Only late in the workshop process, if at all, will the new company be shown a videotape of the Cunningham troupe doing the piece. What the newcomers perform has to be something they developed, not something they copied. As Lent explained this to me, it became clear that the workshop is more than a licensing tool. It is a sort of conjuring, a ceremony through which the Cunningham style is brought back to life. Dance historians are fond of proclaiming that dance, alone among the Western arts, is passed down hand to hand, like folk arts in traditional societies. The artists involved don’t necessarily like hearing about this from non-practitioners. It makes them feel like anthropological curiosities. But in my experience they are also proud of their closeness to the elements. “Having this work in bodies is a good thing,” Lent said of the transfer of Cunningham dances to new troupes. Good for dance, she was saying, but she may also have meant good for the world. Over the centuries, from Plato to Shelley, writers have argued that art improves our morals, makes us stronger, deeper, better—or it should. Of no art, I believe, is this moral bonus more routinely claimed than of dance, both so loved and so disrespected for its identification with the body, the campfire. Other companies have tried to cut back rather than fold. In 2013, the Trisha Brown Dance Company had to contend with the retirement of its founder, probably the most popular of New York’s postmodern choreographers, who’d had a series of small strokes. According to Barbara Dufty, the troupe’s executive director, it was thought that without Brown to create new works, or even to oversee old ones—she could no longer remember them well enough—the company’s job was just to keep alive what it had. The staff would archive Brown’s large œuvre (get the papers into folders, organize the videotapes). They would license pieces to other organizations. And they would perform sitespecific works, which appealed to a large audience and didn’t require the company to obtain bookings, transport huge sets, and the like. Early in her career, Brown wanted no part of the proscenium stage. She had her people walk down the sides of buildings on wires, or do a dance while rafting down a river. By the eighties, however, she was moving toward the mainstream, making works for big stages, with musical accompaniment (another thing that she had eschewed). Once she retired—she died in 2017—the troupe couldn’t perform pieces on that scale, but it could always come up with a few people to do the kookier early work. So, for a while, the curating of Brown’s legacy also changed what that legacy looked like. The earlier, more radical work came back to the fore. Last fall, though, when the company performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, there seemed to be some backsliding, or forwardsliding. Yes, the audience saw some of those naughty early things—for example, “Ballet,” from 1968, in which a dancer walked through the air on two tightropes. (The only one who ever danced it was Brown herself, in a pink tutu.) But there was also something called “Working Title,” a 1985 piece for eight dancers, not a small cast, with a commissioned score by Peter Zummo. The Big Piece form had sneaked up on Brown when she was young and strong, and, now that she was gone, it was sneaking back again. According to Dufty, “People wanted to see the proscenium-stage works”—especially people in Europe, where the company will tour in 2020. Next year also marks the troupe’s fiftieth anniversary, and Dufty told me that this is when the board and the artistic directors will sit down and figure out what the troupe is doing in the future. Another remedy that a founderless dance company can apply is to import work by other choreographers. When Paul Taylor decided that his board was looking at him funny, that’s what he did. For his 2015 Lincoln Center season, he acquired “Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor” (1938), by Doris Humphrey, and an updated “Rite of Spring” (2002-03), by the Chinese-American choreographer Shen Wei. Neither of these dances was in active repertory in New York, and, apart from artistic considerations, that was why Taylor chose them. Like a number of other company directors who were starting to use extramural talent, he said he wanted to honor the old and encourage the young. A few years later, Taylor appointed an “artistic director designate,” Michael Novak, a young member of his company whom Taylor said he chose simply because he liked him. Speaking to Gia Kourlas, of the Times, Novak described the meeting where he was given his new assignment. “Paul said, ‘I have been thinking a long time and I have decided that you’re going to be the one to take over the company once I buzz off.’ I don’t think ‘shocked’ even begins to describe the feeling.” For Taylor, too, despite the casual wording of the invitation, this must have been a wrenching moment. The company was his child, and had been his alone for sixty-four years. The decision was also an expensive one. To help finance the transition, he sold four Robert Rauschenberg works that he owned, and gave the money, more than six million dollars, to the company’s foundation. The Taylor troupe has now embarked on an ambitious international tour—two to three years—as if to nail his story into the annals. After that, Michael Novak will have a big job on his hands. It will be bigger in view of the fact that six out of the sixteen dancers who have recently constituted the company are quitting this year. In an article by Kourlas in the Times, they gave various reasons—they are getting old, they want to have kids, etc.—but, clearly, Taylor’s death is a factor in this exodus. So Novak will be starting, next year, with a company that is almost one-third new. Taylor came late to the challenge of wedging outside choreographers into his shows. Janet Eilber, who took over as artistic director of the Martha Graham company in 2005, has been doing it for more than a decade. At the same time, she says, “it’s not like we’re going to run out of classic Graham works.” There are around a hundred and eighty of them. Other companies, too, have impressive stockpiles: Taylor, a hundred and forty-seven works; Cunningham and Brown, about a hundred each. On a given tour, a company can perform, at each stop, maybe three to seven pieces. This means that a huge number of works go unseen, for what may be many years. Eilber recalls that when the Graham company went to Paris last fall she discovered that “Appalachian Spring” (1944), probably the most famous dance Graham ever made, had never been performed there. It’s one thing for the Graham company, the oldest dance troupe in the United States, to take new choreographers on board. No one is going to mistake their work for Graham’s. But this interpenetration is going on also in younger troupes, companies where you’d expect the founding choreographer to be jealous of his stage time. In 2014, Stephen Petronio’s company inaugurated its “Bloodlines” series, to showcase the work of Trisha Brown and other choreographers who inspired him. “I didn’t fall to earth as a fully formed choreographer,” Petronio said to me. “I came from somewhere.” So did Kyle Abraham, who founded his company in 2006, at the age of twenty-nine. Now he has changed the troupe’s name from Abraham.In.Motion to A.I.M, and he is starting to show the work of other choreographers. Who could object to this? The company directors are sharing, giving back. This is admirable, collegial, responsible. Nevertheless, it violates what was supposed to be the mission of modern-dance companies: to present the vision of one artist. We’re seeing the gradual emergence of the idea of a modern-dance repertory, analogous to that of the ballet repertory (Petipa’s “Sleeping Beauty,” Ashton’s “Symphonic Variations,” and so on), replacing the old idea of modern dance as an unreproducible set of movements—visions, almost—revealed to a group of hierophants by their leader. When the Paul Taylor company, on its big tour, stops in New York this fall, it will perform dances not just by Taylor but also by Pam Tanowitz, Kyle Abraham, and Margie Gillis. All these pieces were commissioned by Taylor before he died, but what do any of them really have to do with him? Or, to put it another way, what will remain of Taylor—not just his repertory but also his style—once this torch-passing goes on for another ten years or so? Almost as a matter of integrity, modern-dance people cannot do So-and-So’s style on Tuesday, then another choreographer’s style on Wednesday. They don’t date; they get married. And once their feet or shoulders have been trained, for years, to do a certain thing, they can’t easily do another thing. Or, if they do it, they can’t easily go back to doing the original thing, and may end up doing some vague, mediocre business in between. I interviewed Mikhail Baryshnikov when he was preparing to dance in Cunningham’s “Walkaround Time” with the Cunningham company, in 1997. Cunningham had very specific notions about the back—he needed it to flex in five ways—and Baryshnikov worked with Cunningham for a long time to get it right, which was not comfortable for a spine that had been disciplined for decades by Russian teachers to work around a consistently upright axis. He longed to do it correctly, he said; he loved Cunningham’s work and wanted to be worthy of it. But he felt, in the end, that he would always be merely approximating it. “I will always be a Russian ballet dancer,” he said. If the dancers have troubles, imagine the situation of the company directors. Those who are trying to revive dances by a dead founder will constantly face complaints by old-timers that the result looks inaccurate, inauthentic. Those bringing in new choreographers will inevitably be met by exclamations of “Him? How could you?” All these companies, in their various ways, are struggling with the question of what modern dance actually is. Does the identity of a choreographer’s work reside in the dancers and their specific way of moving, or does it lie in the dances themselves, if such a thing can be conceived of in an art that has no original texts? (Unlike plays or symphonies, dances don’t exist independently of the manner in which they’re danced. There is no score, no script.) And is it more important for us to preserve the steps, or the ethos that went into their creation? Even as things are saved, something is lost. Whatever the answers, it’s clear that choreographers are now confronting the questions far earlier in their careers. Mark Morris is only sixty-two, an age at which Martha Graham probably didn’t feel that she was mortal at all. But Nancy Umanoff, the executive director of the Mark Morris Dance Group, told me that she has come up with a plan called Dances for the Future. It goes like this: Every year, Morris, who is a fast worker, will create one more dance than he has committed himself to do, and the extra one will not be publicly performed. It will be videotaped, from this angle and that; it will be recorded in dance notation; the dancers on whom it was created will be interviewed; the set will be designed (but not built). All this material will then be put in a drawer, where it will remain as long as Morris is alive. If, after five to seven years, the dance still hasn’t been performed, it will be pulled out and reinflated, as it were—new videos, new interviews, new cast, maybe. If it’s still not needed, it will be stowed away again. One piece, to Scarlatti, is already in storage. It was made last year. But how will it be for the company to try to call back into being a dance that hasn’t been performed in a number of years, with a cast that has never performed it in front of an audience? Morris said to me recently, “You know ‘Love Song Waltzes’? You just saw us do it in August? We hadn’t done it in four years, and only one-third of the dancers had ever performed it before. It looked O.K., right?” “But the new dancers were rehearsed by you,” I said. “What if you aren’t there?” “No problem,” he replied. “I won’t know. I’ll be dead.” ♦ Published in the print edition of the July 1, 2019, issue, with the headline “Must the Show Go On?.” Joan Acocella has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1995. She is the author of, most recently, “Twenty-eight Artists and Two Saints.”