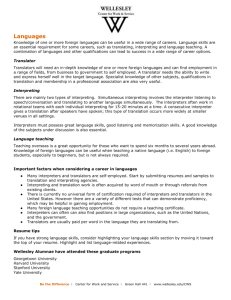

Lecture 1. Introduction to the profession of "translator" About 40,000 translated publications are published annually in the world, i.e. over 100 books per day. How did the translation begin? In ancient Carthage, translators were so numerous and in demand, and their profession was so respected and honorable, that they constituted a separate caste of “professional translators”, had a special legal status and were exempted from performing any duties, except for translation. Even outwardly they differed from others: they walked with shaved heads and wore a tattoo of a parrot. A parrot with open wings meant that its owner knew several languages, a parrot with folded wings meant that the owner knew only one language. So the parrot became a symbol of translators. In ancient Greece, the god Hermes was called the "translator of all languages." On his behalf, the word hermeneutics was formed, meaning the ability to interpret, interpret, explain and is often used in modern translation theory to denote the stage of understanding, deciphering the original speech message. So Hermes can also be a symbol of the translator. How strongly the translator influences, his subjective understanding of the text and the choice of translation option for reality are proved by numerous facts from the history of mankind. Bible translations are a prime example. The journal of the International Federation of Translators is called BABEL, the Hebrew name for Babylon, famous for its mythological interpretation in the Bible. Although the origin of the name of the city has nothing to do with the legend of the confusion of languages. In Hebrew there was a word consonant with the word BABEL - the verb form [bil'bel'], meaning confused.This similarity of two words formed the basis of the biblical myth. In the Akkadian language, otherwise called Babylonian-Assyrian, there was a word Bab-Ilu, meaning the Gate of God. This word, apparently, became the name of the city. Translations of biblical texts performed a huge civilizing mission in the history of the cultural development of mankind. These translations served not only to disseminate Christian ideas, but were also the main tool for the formation of new languages. Together with the translation of the Bible, the educators Cyril and Methodius brought writing to the Slavs. Thanks to the translation of the Bible into German by Martin Luther, the people of Germany received their single national language. The English language owes much of its perfection to the translation of the Bible known as the King James Version. In the history of biblical translations, one can distinguish not only three main periods, but also significant events that played a special role in the development of culture. In the first, ancient period, the famous Septuagint and the Vulgate were such events. Translators aid communication by converting written information from one language into another. The goal of a translator is to enable the public to read the translation as if it were the original. To do that, the translator must be able to write sentences that flow as well as the original, while keeping ideas and facts from the original source accurate. They need to consider any cultural references, including slang, and other expressions that do not translate literally. Translators must read the original language fluently but may not need to speak it fluently. They usually translate only into their native language. Nearly all translation work is done on a computer, and translators receive and submit most assignments electronically. Translations often go through several revisions before becoming final. Translators typically do the following: Convert concepts in the source language to equivalent concepts in the target language Speak, read, and write fluently in at least two languages, including English and one or more others Relay style and tone Manage work schedules to meet deadlines Render spoken ideas accurately, quickly, and clearly Lecture 2. Translation profession from the point of view of a translator Meeting customer requirements is a vital necessity for a translator, but it is important to see these requirements through the prism of your own view of the job: strive to provide the reliability customers need, based on the concept of professional pride (including passion and ethical standards) - see timeliness as a way to increase your income , achieved through the acceleration or efficient distribution of work, as well as by raising the status of the profession: to believe that work should bring pleasure. Who are translators? What does it take to become a translator? Who likes to sit at a computer or in a courtroom day after day, turning words and expressions of one language into words and expressions of another (not to mention the fact that not everyone can do it)? What a boring and thankless job! For many people, it is. Some people like it at first, but then they get tired, burn out and change their occupation. Someone can only do translations along the way, for several hours a day, a week or even a month. During the day, he composes some texts, works as a teacher or editor, and translates for an hour before bedtime or a couple of days off a month. For the sake of money or for pleasure, for the most part (I want to believe) for both reasons. If he comes across a large order at a good price and there is free time, he quits the rest of his classes and translates for a week in a row for 8-10 hours a day. But after that he feels completely exhausted and strives to return to his main work.For others - and these are probably the majority among translators (although there are no statistics on this) - translation is the main activity, but they do not burn out. How do they do it? What abilities do you need to constantly become a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer, a poet or a manager, even if only for a while and only on your computer screen? Are they talented actors who easily switch from one role to another? How do they know so many terms? Are they walking dictionaries and encyclopedias? Or experts from “What? Where? When?". But, in short, yes, translators (especially interpreters) must have an acting streak, they must have the gift of imitation and reincarnation. Yes, they need to develop an amazing memory that will allow them to recall a word (often in a foreign language) that they have heard only once. Translators are greedy devourers of all kinds of literature. Usually they have started four books at once in several languages: fiction and documentary, technical and humanitarian, all sorts of different. They absorb life impressions just as eagerly: they travel a lot, live abroad for a long time, learn foreign languages, get acquainted with a foreign culture. And at the same time, they constantly monitor how others use the language: a plumber, a school teacher, a saleswoman in a neighboring store, a doctor, a bartender, friends and colleagues from different rotons and social classes, etc.The profession of an interpreter is often called an additional profession - many first acquire a specialization in some other area, sometimes even in several, and become translators after a voluntary or involuntary dismissal or moving to a country where there is no opportunity to work in their main specialty. As translators, they often help communicate with their former colleagues who speak different languages. Any meeting of translators strikes with a variety of participants. And not only because a good half - people from different countries, almost all - lived abroad, and the majority - easily switch in conversation from one language to another. The main thing is that translators inevitably carry within them a wealth of several different selves or personalities, each of which is ready to unfold on the computer screen when a new text appears or on the air when a new speaker enters the stage. The group of translators always seems to be larger than it really is. The main characteristics of a good translator naturally meet the customer's expectations: it is reliable, works quickly and at real prices. However, from the point of view of the translator, this is explained by completely different reasons. For him, reliability is important as a matter of professional pride, which includes other elements that are practically indifferent to the customer. Speed matters only as a means of increasing income, which can be increased in other ways. And most importantly for the translator, perhaps most importantly, the pleasure he gets from his work is a factor that has negligible significance for an outside observer. Let's look at these three inner needs in order: professional pride, income, and pleasure. Professional pride From the customer's point of view, it is essential to be able to rely on translation, and not only on the text, but also on the translator himself, on the entire translation process as a whole. Since this is important for the payer, it is also important for the translator. The practical need to keep a job (for full-time translators) or continue to receive orders (for freelance) determines the willingness to meet the requirements of the customer. But more important than money and maintaining a position for a translator is professional pride, decency and self-esteem. We all want to know that we are doing an important job, we are doing it well, and that the people for whom we are doing it appreciate our work. In fact, most people will prefer a job they feel professional pride in over one they don't believe in, even if the latter pays more. Despite the importance of high earnings (who would refuse it!), big money brings little joy if you can not be proud of your work. As a rule, the source of pride for most translators is their reliability, professional dedication and adherence to ethical standards. Reliability In the field of translation, reliability largely comes down to customer satisfaction: translating the right texts in the right form and on time. In an effort to fulfill these requirements, the translator sometimes faces unsolvable tasks, sometimes meeting the requirements damages his personal life or causes moral torment, often physically and mentally exhausting. If the tasks are feasible in principle, then in many cases the translator considers it a matter of professional honor to ensure reliability, pushing other considerations into the background. He is ready to sit up all night on urgent work, canceling a date because of it, or translate a text that contradicts his political or moral convictions. It is the professional commitment to reliability that drives translators to spend long hours looking for a single term. How much do they get paid for the time spent in this way? Virtually none. But it is extremely important for them that everything is correct: the correct term is found, the correct spelling is chosen, the correct wording and the correct functional style. And not just because the client expects it - if he does not do it right, then his professional pride will suffer and he will not receive full satisfaction from the work.Professional passion For the customer, this does not really matter, but for us translators, it is extremely important which professional unions or associations they belong to, which conferences of translators they go to, which courses they attend, how they maintain contacts with other translators in their region or their language pair. Sometimes such professional activity helps to better translate what matters to customers, and thus allows us to be more proud of our reliability. More importantly, however, all of this helps translators feel more comfortable in their role as an interpreter, reinforcing the selfesteem that keeps them going through boring, repetitive, or poorly paid assignments. Reading books and articles about translations, talking about translations with colleagues, discussing and solving problems related to linguistic conversions, customer requests or non-payments, as well as attending translation courses and conferences, getting acquainted with technical innovations in their field, buying and mastering new software and hardware - all this makes us feel not isolated, poorly paid losers, but real professionals, surrounded by other professionals who care about the same issues as translators. Active interaction with colleagues gives them the knowledge and confidence they need to resist unreasonable demands by educating clients and employers, rather than humbly submit to them with inward resentment. It helps to realize that customers need translators no less than they need them: they have what translators need - money; translators have what customers need - the ability to translate. And they can sell their skills with a sense of professional confidence and power, rather than a humiliated, subservient position that forces them to agree to any terms. Ethical Compliance The ethical standards of a translator are usually defined rather narrowly: it is unethical to distort the source text. This restriction is unnecessarily harsh even from the client's point of view: in many cases, the translator is directly asked to "distort" the source text in a certain way, for example, when reworking material for television, a children's book, or an advertising campaign. From the translator's point of view, ethical norms look even more complicated. For example, what should you do if you have been ordered to translate a text that you think is offensive? In other words, what should a translator do when professional ethics (loyalty to the person paying for the translation) conflicts with personal ethics (political or moral convictions of the translator)? What is a feminist to do who has been ordered to translate a text filled with male chauvinism? As long as the field of translation was dominated by an outside view, such questions did not arise and could not arise. The translator translates what he is ordered and does it the way the customer needs. The translator's own point of view has nothing to do with the translation process. However, from the inside, these questions should be asked. Translators are ordinary people with their own opinions, preferences, hopes and feelings. If a translator is constantly commissioned to translate texts he considers vile, he may suppress his disgust for weeks, months, perhaps even years, but not forever. A translator, like any professional, wants to be able to be proud of what he does.If a serious contradiction between his personal convictions and the ethical requirements imposed on the profession from outside does not allow him to feel such pride anymore, he will eventually have to decide where and under what conditions he wants to work. Nowadays, translators are increasingly striving to harmonize their professional activities with their moral principles. For example, translator Suzanne Lobin-yer-Harwood, a feminist from Quebec, said she no longer translates documents written by men: when translating such texts, the temptation to speak from a male perspective is too great, and she is disgusted by the suppression of her own personality. When translating literary works written by women, she does her best to help develop a female-oriented language in the target culture. Susan Gil Levine writes in her book that when translating the works of South American writers, she tries - often with the participation of the authors themselves - to remove outrageous manifestations of their male chauvinism. A British translator based in Brazil and active in local and international environmental groups is commissioned by an agency to do a full-time job of translating everything printed in Brazil about smoking into English. Every week, she receives a photocopy package of materials, most of which are about scientific research conducted in Brazil and other countries on the dangers of smoking. As an active opponent of smoking and a fighter against the tobacco industry, she enjoys translating these texts. In addition, the texts are relatively simple, many of them are small modifications of the same press release, and they pay well for this work. However, she gradually begins to have ethical doubts. Who in the English-speaking world is so interested in what they write in Brazil about smoking, and rich enough to pay her to translate all this material into English? Surely this person or organization cares not only about Brazil, there are probably dozens of translators doing this kind of work all over the world. In each country, a local translation agency hired a person to translate publications in that country. Who can be the organizer of such a project, except for a large tobacco company from the USA or England? She begins to read the translated materials more carefully and finally guesses between the lines that the orders are coming from the largest tobacco company in the world, which burned thousands of acres of the Amazon rainforest to dry tobacco leaves, from a neo-colonial corporation that destroyed not only the rainforest ecosystem, but also the economy of the Indians living along the Amazon. All these thoughts gradually cause her dislike for work: after all, in fact, she helps the largest tobacco company to spy on the opposition. Lecture 3. Community interpreting Community interpreting is a type of interpreting service which is primarily found in community-based situations. It is a service provided in communities with large numbers of ethnic minorities, enabling those minorities to access services where the language barrier might be an obstacle. Contexts in which such interpreters are necessary are typical include medical, educational, housing, social security and legal areas. Community interpreting includes sign-language as well as spoken language interpreting. What is the role of the Community Interpreter? A language interpreter is a conduit for 2 or more people who do not speak the same language. The primary role of the interpreter involves the oral rendering of meaning from one language into another without changing content, register or tone An interpreter: • Is a language assistant • Is fluent in two or more languages • Understands their limitations • Does not advocate for either party in an interpreting session • Does not let personal opinions enter into their work • Maintains a current knowledge of vocabulary and terminology • Is not a “friend” to the client • Does not offer counseling nor advice Interpreting Techniques and Modes Interpreting is conducted according to established techniques and modes. Different settings call for different techniques. It is important to use the appropriate technique for the setting. There are two main interpreting modes. These are simultaneous and consecutive. There are also other modes, such as summarizing, descriptive, etc., but these are not typical and are used discriminately in select situations. Simultaneous and consecutive are the primary and standards modes. Simultaneous Mode The interpreter begins to interpret the message while the speaker is still talking. The interpreter keeps a few words behind the speaker. Consecutive Mode The interpreter waits for the speaker to pause and then accurately interpreters what the speaker has said. Usually allows for a few sentences of information to be spoken before pausing. Settings and Styles for Interpreting Interpreting happens in a variety of different settings. While community interpreting is perhaps the oldest form, it is the most recent to join the professionalization rank. When people think about interpreting they often envision booths, headsets, microphones, and a large auditorium or a United Nations conference room. But interpreting happens everywhere. From the smallest community-based office to the largest conference rooms. Below is a listing of different settings and styles for interpreting. 1. Conference Interpreting • Conference setting involves specialized equipment and interpreters skilled in simultaneous mode 2. Court Interpreting • Court/legal setting - may involve specialized equipment. In more and more situations, court interpreting is conducted in simultaneous mode. 3. Diplomatic Interpreting • Interpreters for this setting are usually citizens of the country for which they interpreting and must know a range of subjects and work specifically for the diplomat to which they are assigned. 4. Business Interpreting • Business meeting/conference setting - may involve special equipment. • Interpreters for this setting may have specialized knowledge and may also act as a cultural chaperone. 5. Community Interpreting • Community level - involves social services, education, health care, police or any service that is community based