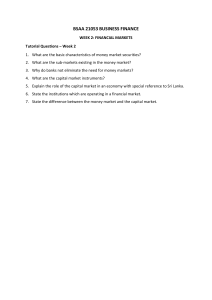

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310170139 Conflict in Sri Lanka: A Study on Peace Negotiations during the Civil War 1984-2008 Article · September 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 3,182 1 author: Osantha Nayanapriya Thalpawila University of Kelaniya 18 PUBLICATIONS 15 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Post war reconstruction View project Politics In Indian Ocean View project All content following this page was uploaded by Osantha Nayanapriya Thalpawila on 14 November 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Conflict in Sri Lanka: A Study on Peace Negotiations during the Civil War 1984-2008 Osantha Nayanapriya Thalpawila Department of Economics, University of Kelaniya osantha@kln.ac.lk Abstract The ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka emerged in the post independent period with the increasing polarization of Sinhalese and Tamil identities into almost warring camps. The Sri Lankan military forces launched their operations and the civil war spread out destructively in those regions causing heavy human and economic cost to the country. Similarly, the Sri Lankan government as well as foreign countries carried out negotiations and peace efforts to achieve a peaceful solution to the war and find a political solution to the problem. The aim of this paper is to look into the peacebuilding negotiations and their out comes during the conflict affected period. The secondary data collected from the contemporary literature which was used to analyse the peace negotiations during 1984-2008. Several attempts were made to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Sri Lanka with help of the foreign countries as well as the Sri Lankan government itself. All those attempts were failure since the rise of Sinhalese and Tamil extreme nationalism. ` (1) Introduction Civil wars usually with a ceasefire or peace agreement followed by negotiations between the conflict parties.1 However, the civil war in Sri Lanka ended in 2009 with a military solution in what is reported as an exclusive situation in recent history. The lessons of past errors and experiences of war stress to avoid another war 1 See O.Ramsbotham T. Woodhouse, and H. Miall, Contemporary Conflict Resolution : The Prevention, Management, and Transformation of Deadly Conflicts. 3 rd ed. (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2011) 172-173 and build a long lasting post war peace in Sri Lanka. Further, the past lessons stress the urge for a suitable political construction for address issues of separatism in Sri Lanka. Although the government finally resorted to military operations as a solution to the conflict in Sri Lanka, it is worth mentioning that many attempts were made to reach a peaceful solution to the ethnic problem through negotiations. The following history of the peace processes discusses that were attempted in Sri Lanka to arrive at some mutually acceptable solution to restore long lasting peace in the country. (2) The Peace Negotiations from 1984 to 1993 The peace negotiations conducted from 1984 to1993 were arranged through Indian intervention and facilitation to hammer out a political solution to the conflict in the country. In 1985 India was involved in facilitating the Government of Sri Lanka to inaugurate negotiations with the Tamil militant organizations and the Tamil political parties at the first ever peace talks. The talks were held in Thimphu, the capital city of Bhutan, between the delegations of the Sri Lankan government, the Tamil political parties and the militant organizations.2 During the talks in Thimphu, the Tamil groups put forward four demands to the Sri Lanka government delegation as a solution to the conflict. They were,(1) Recognition of the Tamils of Sri Lanka as a distinct Nation, (2) Recognition of an identified Tamil homeland and the guarantee of its territorial integrity, (3) Recognition of the inalienable right to self – determination of the Tamil nation, and (4) Recognition of the right of full citizenship and the fundamental rights of all Tamils who look upon Sri Lanka as their country.3 The Thimphu talks did not curb the spread of violence. The government was at the time planning to grant citizenship to the Tamils of Indian origin and that was not in 2 Five Tamil militant groups – LTTE, PLOTE, TELO, EPRLF and EROS participated to the Thimphu talks with the TULF on behalf of the Tamil parties. 3 Asoka Bandarage (2009) The Separitist Conflict in Sri Lanka. New York, Bloomington: iUniverse, p. 125 conflict with the Tamil demands in Thimphu. But the government rejected the first three demands, as those would in effect support the demand of the Tamil militants for a separate state for the Tamils in Sri Lankan territory.4 The head of the Sri Lankan delegation, Mr. H.W. Jayawardene announced, “They must be rejected for the reason that they constitute a negation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka; they are detrimental to a united Sri Lanka and are inimical to the interests of the several communities, ethnic and religious in our country.”5 Although the Thimphu talks were unsuccessful and were not continued further, the Tamils put forward their demands persistently in their struggle for a separate state. The Thimphu talks revealed the immaturity of both parties in connection with techniques of political negotiations as they expected to reach a fruitful decision in the first attempt at discussion. During the next couple of years the Tamil militants‟ violence spread throughout the North and East of the country and the government‟s military operations were strengthened to cope with the situation. When the war became very intense in July 1987 India intervened and compelled the Sri Lankan government to halt its military operations. Then, the Indian government persuaded President Jayawardene to sign the “Indo-Sri Lanka Peace Accord” to end the Sri Lankan ethnic conflict through a political settlement.6 According to the “Indo-Sri Lanka Peace Accord” the government devolved power at the provincial level to the Northern and Eastern provinces within the unitary sovereign state of Sri Lanka under a special amendment (the 13th) made to the constitution of Sri Lanka. The agreement clearly determined the province as the unit of devolution. Among the other important 4 S. L. Gunasekara, Tigers, 'Moderates' and Pandora's Package, (Colombo: Sri Lanka Freedom Press, 1996) 5 Ketheeswaran Loganathan, Sri Lanka: Lost Opportunities (Colombo: CEPRA, 1996) p. 105 6 Indo – Sri Lanka peace accord was signed by Rajiv Gandhi the Prime Minister of India and J. R. Jayawardene, the President of Sri Lanka on 29 July 1987 at Colombo, Sri Lanka. features of the peace accord was the option of merging the Northern and the Eastern provinces temporarily to form one administrative unit with one elected provincial council, one chief minister and a board of ministers.7 A future referendum was to be called to obtain the opinion of people in the Eastern Province on the question of amalgamation with the Northern Province. The accord also called for Tamil to be an official language and re-imposed English as an official language along with Sinhala.8 The peace accord further agreed on the following points: (1)to cease hostilities within 48 hours between government forces and Tamil militant groups, (2) the Tamil militant groups were to surrender their arms (India would send her armed forces to Sri Lanka to supervise this task),9 (3) the government forces were to be confined to their barracks, (4) the Sri Lankan President agreed to grant a general amnesty to the political prisoners, (5) India agreed to provide any required military assistance and to take all necessary steps to prevent the use of Indian territory by any party to launch attacks against the unity, integrity and security of Sri Lanka.10 The Indo-Sri Lanka peace accord was not a permanent solution to the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka. On the one hand, the LTTE did not surrender all of its arms to the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) and later began to fight with the IPKF 7 This was introduced to create a single administrative region for Tamil speaking people. Both provinces were merged temporarily by establishing the North-East Provincial Council in 1988. However, the government of Sri Lanka postponed the holding of a referendum to determine the peoples‟ wish for merging. In 2007 the Supreme Court gave its verdict to de-merge both provinces. 8 The 13th amendment to the Sri Lankan constitution was passed on 14 November 1987 to make certain amendments to the provincial council system and the official language policy. 9 India sent her troops (Indian Peace Keeping Force [IPKF]) to the North of Sri Lanka to assist in the cessation of hostilities and surrender of arms on 30th of July 1987 under the terms of the accord. The troop size was between 70,000 - 105,000 personnel, exact figure not revealed. See S.U. Kodikara, „The continuing crisis in Sri Lanka: The JVP and the Indian troops and Tamil politics‟, Asian Survey, vol. 29, no. 7, July 1989, pp. 716-724; Ravi Rikhye, Economic and Political Weekly, March 1989. 10 Further reference, see S.U.Kodikara, Indo - Sri Lanka Agreement of July 1987. (Colombo: Dept. of History and Political Science, University of Colombo, 1989); K.Rupasinghe,Negotiating Peace in Sri Lanka. 2 ed. Vol. 1, (Colombo: The Foundation for Co-Existence, 2006); R. Edirisinghe, M. Gomez, V.T. Tamilmaran, A. Welikala, Power Sharing in Sri Lanka: Constitutional and Political Documents 1926-2008. (Colombo: CPA and Berghof foundation for peace support, 2008 ); Asoka Bandarage (2009) op cit. itself.11 On the other hand, most of the Nationalists in the government as well as the opposition parties resisted the Indo-Sri Lanka pact because they felt that it undermined the sovereignty of Sri Lanka.12 The Sri Lanka Muslim Congress did not support the peace accord and argued that it would invite not only a Tamil-Muslim conflict but also a Tamil-Sinhala conflict in the region.13 Although the government established the provincial council system throughout the provinces in Sri Lanka, it was not successful in the North-East Province. The government established the North-East Provincial Council (NEPC) by conducting an election in November 1988 and that resulted in Mr.Varadharaja Perumal being appointed as the Chief Minister of the provincial council. “Obviously, the Indian imposed NEPC was not representative of the Tamil, Sinhala, Muslim people of the North and East. Nor was it supported by the Sri Lankan government. Not wanting to settle for anything less than Eelam under its own hegemony, the LTTE vehemently opposed the NEPC despite the fact that the council laid the basis for provincial autonomy under Tamil dominance. The EPRLF was not able to establish the NEPC as an independent political entity. And from the council‟s inception, India was saddled with the task of maintaining a puppet regime.”14 11 If the EPRLF, TELO, PLOTE, ENDLF and EROS abandoned secessionism and came to join the democratic process in Sri Lanka, the LTTE was against the peace accord and did not surrender their arms and soon after fell in to a war with the IPKF. See S.U.Kodikara (1989) ibid. 12 The Indo-Sri Lanka peace accord was welcomed by only non – JVP Sinhala left wing parties who believed in a political settlement through devolution of power in the country. People‟s Liberation Front [JVP] a hardline nationalist Sinhalese political party launched an anti-state revolution in 19871989 in the south of the country against the Indian intervention as well as the anti-democratic policies of J.R. Jayawardene‟s government. The JVP insurgency was crushed in November 1989 after it had left 60,000 Sinhalese dead in the South of the country. See C.A. Chandraprema, Sri Lanka: The Years of Terror: The JVP Insurrection 1987-1989. (Colombo: Lake House, 1991). 13 M.H.M. Ashroff, "The Muslim Community and the Peace Accord." Indo-Sri lanka Peace Accord, 29 July 1987, Vol26, no 1 (1987): 48-75. 14 Asoka Bandarage (2009) op cit., p. 151 The Chief Minister of the provincial council of North and East put forward a 19point demand that forced the government of President R. Premadasa15 to dissolve the provincial council. In addition, the LTTE commenced fighting with the IPKF causing heavy losses to the Indian troops as well as to itself.16 The IPKF was no longer a peace keeping force for the Tamils in the North or the East, because several human rights violations were committed by the IPKF against them, which made a mockery of their peace keeping credentials.17As there was a growing opposition movement by the Sinhalese nationalist forces in the South of the country against the IPKF, the situation further worsened. R. Premadasa won the presidential election in November1988 and was sworn in as the second Executive President of Sri Lanka.18 The LTTE agreed to a ceasefire with the new government, responding to the offer made by President Premadasa in April 1989.19 The peace talks commenced on 3rd May 1989 in Colombo and recommenced on 6thMarch 1990 in Jaffna.20In April 1989 President Premadasa called for India to quit the country soon but Rajiv Gandhi‟s government refused to withdraw the IPKF so early. It must be mentioned here that the Premadasa regime then secretly allied with the LTTE and provided them arms to strengthen the LTTE‟s military power against the IPKF.21The IPKF survived in Sri Lanka until a new Indian government headed by Prime Minister V.P. Singh withdrew the IPKF troops from 15 President Ranasinghe Premadasa, former Prime Minister in Jayawardene‟s government won the presidential election in 1989 and was sworn in as the 2 nd executive President in Sri Lanka. He was against the Indo-Sri Lanka peace accord from the very beginning. 16 According to estimated reports 1,555 IPKF soldiers including 49 officers died during the mission in Sri Lanka and the IPKF killed 2,592 LTTE cadres. See ibid., p 153 17 See S. U. Kodikara (1989) op cit. 18 President Premadasa protested against the Indian intervention, when he was the Prime Minister in President Jayawardene‟s government. 19 President Premadasa‟s government declared a ceasefire and offered the LTTE a peace package. However, India did not acknowledge this and refused to withdraw its troops from Sri Lanka. 20 This is the 2nd attempt at peace talks between the GOSL and the LTTE. 21 The government supplied millions of rupees worth of arms and vehicles to the LTTE secretly to attack the IPKF in 1989, during the war against the IPKF by the LTTE. See R.Gunaratne (1998) Gunerathna, R. (1998). Sri Lanka’s Ethnic Crisis and National Security. Colombo: South Asian Network on Conflict Research. Sri Lanka in March 1990.22The following year, the LTTE assassinated the Indian exPrime Minister Rajiv Gandhi during an election campaign in Tamil Nadu and this incident shook everyone up very badly. The Indian government reacted very strongly and completely dropped their support for the LTTE and further, banned it as a terrorist organization in India.23On the 1st of May 1993,the Sri Lankan President R. Premadasa was assassinated by the LTTE while he was participating in the “World Workers' Day” rally in Colombo.24Though the Indian intervention was not able to bring peace to the country, the government of President Premadasa did make an attempt to bring about a negotiated settlement to the conflict. (3) Cross Party Selecting Committee (1991-1993) The Premadasa government constituted a “cross party selecting committee” to find a solution to the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka in August 1991. The main political parties and seven Tamil political parties participated in it. The selecting committee met 49 times between November 1991 and 1993.25 Seven Tamil political parties submitted their proposals to the committee and these came to be known as the „Four Point‟ formula. The proposals were as follows: (1) A permanently merged North – East province, (2) Substantial devolution of power to the North - East province, (3) An institutional arrangement within the merged North - East province for the Muslims, guaranteeing their cultural identity and security, (4) The Sinhalese in the North and East to enjoy all rights that the minorities enjoyed in the rest of the 22 Rajiv Gandhi‟s congress party government was defeated in the general election in 1990. Since the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991, Indian involvement in the Sri Lankan crisis has remained highly neutral up to the post-war period. 24 The LTTE aimed to assassinate the National leaders of the country as a strategy to eliminate the leadership of the country. 25 R. Edirisinghe,Gomez, M., Tamilmaran,V.T., Welikala, A.,(2008). Power sharing in Sri Lanka: 23 Constitutional and political Documents 1926- 2008. Colombo: CPA and Berghof foundation for peace support. p. 410 country.26A committee report called the Mangala Moonesinghe report was released in November 1993 and this contained the views of the majority. According to that, the committee had suggested an “Apex Council” as a unit of devolution. It had further recommended separate councils for the North and the East.27 The other important development was that a consensus was reached between the two major political parties, the UNP and SLFP that power sharing should be in the mould of the Indian federal model.28 The idea of an Apex council was rejected by the Tamil political parties as well as by the Sinhalese Nationalist party – MEP. The LTTE rejected the proposed Apex council saying that they were not satisfied with the powers devolved to the councils and the MEP did not agree to broad power sharing with the minorities as that would be harmful to the unitary structure of the country. Therefore, the Cross party selecting committee was unable to reach a consensus on the ethnic conflict in the country. (4) The Peace Negotiation Process (1994- 2002) In August 1994, the People‟s Alliance (PA) led by the SLFP won the general elections and its candidate Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumarathunga won the presidential election with an overwhelming majority. The new government of Sri Lanka headed by President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumarathunga of the PA29 resumed the peace talks with the LTTE in Jaffna, in October 1994. During the time of President Kumarathunga‟s regime four rounds of peace talks were held in Jaffna with the LTTE.30 After signing a ceasefire agreement with the LTTE in January 26 The seven Tamil political parties are EPRLF, ACTC, TELO, DPLF, EDF/EROS, ENDLF, TULF See R. Edirisinghe et al. (2008) op cit. 28 Ibid., p 410. 29 Mrs. Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumarathunga who headed the PA came to power as the Prime Minister in August 1994 and three months later she was elected as the 4th executive President of Sri Lanka at the presidential election held in November 1994. 30 This was the 3rd attempt at peace talks between the GOSL and the LTTE. 27 1995, the government put forward its proposals for long lasting peace within a power devolution package.31 President Kumarathunga‟s proposal consisted of wider power devolution based on the union of regions. Each of the existing provinces in Sri Lanka will be converted to a region of the republic with a separate regional council and a governor. The boundaries of the North and the East provinces were to be redrawn to create a single North East region.32 Although the devolution proposal of the Kumaratunga government was highly praised by the international community, it was not supported by the local political streams. The main opposition party and the Sinhala nationalist forces were against the new draft of the constitution in the parliament as well as outside it. As soon as the peace attempts broke down hostile activities flared up again between the government forces and the LTTE. As a direct consequence, hundreds of human rights violations were reported during 1995- 2001. An LTTE suicide bomber attacked President Kumarathunga while she was participating in a PA election campaign in Colombo in 1999,causing injuries to her.33 (5) Norwegian – Facilitated Peace Process (February 2002 to January 2008) During the 26 years of civil war between the government and the LTTE, the peace negotiation mediated by Norway was another important attempt at peace in Sri Lanka.34 The role of the Norwegian government as a facilitator included building information, minimizing misunderstandings and creating an ambience conducive to 31 See R. Edirisinghe et al. (2008) op cit. See ibid. 33 See K.M. de Silva (2012) op cit. 34 See Jayadeva Uyangoda, „Government –LTTE Negotiation Attempt of 2000 through Norwegian Facilitation: Context, Complexities, and Lessons‟ in Rupasinghe, K. Negotiating Peace in Sri Lanka. 2 ed. Vol. 1, (Colombo: The Foundation for Co-Existence, 2006) 32 the peace process‟s progress.35 In 1999 President Kumaratunga invited Norway to act as a peace mediator in connection with the 18 year war in Sri Lanka. 36 However, President Kumarathunga‟s government lost its parliamentary majority and the PA government was defeated in the parliamentary elections in February 2001. The UNP allied with minority parties as the United National Front (UNF) and came to power with a narrow margin of victory under the leadership of Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe. Therefore, Norway mediated the peace talks with the new government by coordinating communication between the two parties and arranging logistics during the peace talks.37 As the LTTE unilaterally agreed to a ceasefire with the UNF government, Norway facilitated the signing of the ceasefire agreement (CFA) between the Government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE on 21st February 2001. The CFA mediated by the Norwegian government was one of the important attempts at taking forward the peace process in Sri Lanka. “The objective of the 2002 ceasefire agreement was to find a negotiated solution to the on-going ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka. While it noted that other groups have also suffered the „consequences of the conflict‟, it upheld the dualistic characterization of the conflict by recognizing only the government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE as the two parties to the conflict. Bypassing elected members of parliament representing non-LTTE Tamil interests and choosing 35 G. Samaranayake, "Third Party Mediation of Norway in the Conflict Resolution of Sri LankaProblems and Prospects." In Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding in Sri Lanka, edited by Karl Fischer, V.R.Ragawan.(New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing, 2005) 36 Norway is outside the region of South Asia, but its commitment to building peace and experience as a third party by its involvement in the middle-east renders it eligible for the Sri Lanka peace process. Norway has worked as a peace mediator before this, eg. Oslo accord in Israeli - Palestine peace process in 1993. Further, the LTTE also trusted Norway as a mediator. 37 Norwegian parliamentarian Erik Solheim, Minister of the Environment and Minister of Development Cooperation, was appointed as the special advisor of the Norwegian Foreign Ministry in the Sri Lankan peace process. to negotiate with the unelected LTTE, the agreement accepted the LTTE as „the sole representative of the Tamils‟.”38 In addition to the CFA, the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM) was appointed to supervise the implementation of the CFA.39 Further, The Tokyo Conference on ReConstruction and Development of Sri Lanka was nominated for funding economic development and reconstruction projects in the North and East on 10th June 2003.40 During the Norwegian mediation for Peace process in Sri Lanka six rounds of peace talks were held in Thailand, Norway, Germany and Japan.41 The first round of peace talks were held in Thailand and issues on assurance of safety, security and identity of all communities in Sri Lanka, rehabilitation, and resettlement of displaced persons were discussed.42 The second round was held in Thailand and the discussion focused on humanitarian and economic issues. The third round was in Oslo and both parties agreed to explore the options of a federal government. The fourth and fifth rounds of talks were held in Oslo and Thailand and the security issues were discussed. The sixth round of discussions was held in Japan and issues of child abduction, recruitment of soldiers, devolution of power, rehabilitation and reconstruction were discussed.43 It was a significant development of the peace process that both parties had agreed to a federal model as a political solution to the conflict in these negotiations. During the peace negotiations, the key part was introducing an interim arrangement that would permit the LTTE to participate in the governance of the 38 Asoka Bandarage (2009) op cit., p. 182 The SLMM comprised members from the Nordic countries - Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden. 40 The United States, Japan, Norway and the European Union were appointed as Co-chairs of the Tokyo conference. 41 This is the 4th attempt at peace talks between the GOSL and the LTTE. The sessions were carried out on 16 September 2002 at Sattahib Naval base in Thailand, 31 October 2002 at Rose garden hotel in Thailand, 2 December 2002 at Oslo in Norway, 6 January 2003 at Rose garden hotel in Thailand, 7 February 2003 in Berlin in Germany, 18 March 2003 in Kanagawa in Japan. 42 See G. Samaranayake, (2005) op cit. 43 Ibid. 39 North and East. The LTTE demanded a suitable mechanism to engage in direct reconstruction and development work in the North.44 On 31st October 2003, the LTTE put forward its own peace proposal, the so called “Interim Self-Governing Authority” (ISGA), and it proposed an authority that would be fully controlled by the LTTE in the North and East.45 According to the proposal an interim self-governing authority in the North and the East would be controlled by the LTTE for six years and then they would call for a referendum to continue it. The political forces in the South were suspicious of the LTTE proposal, saying that it would allow the LTTE to fully control the North and the East totally for a certain period.46 They pressured President Kumarathunga to take action on the Prime Minister of the UNF government. The President took over three key ministries under the ministry of defence and dissolved the UNF government.47As the President had dissolved parliament the peace talks were discontinued for some time. Within a year, six rounds of talks had been held between both parties, mediated by Norway, but all that could not produce a successful outcome for the conflict.48According to some critics, the peace talks were not aimed for a long lasting peace but for other benefits. 44 See R. Edirisinghe et al., (2008) op cit. See Rohan Edirisinghe, Asanga Welikala, „The Interim Self Governing Authority proposal: A Federalist Critique‟ in Rohan Edirisinghe & Asanga Welikala (eds) In Essays on Federalism in Sri Lanka (Colombo : CPA, 2008) Chapter xii 46 Some Tamil political parties such as the EPDP that allied with the Southern political parties, was not happy with the decision to appoint the LTTE as the sole representative of the Tamils. 47 According to the constitution the President can take over the cabinet ministries. See Article 30-41of the vii chapter of the Sri Lankan constitution in 1978. 48 The LTTE was not invited to the talks in Washington DC on reconstruction and development in Sri Lanka held in April 2003. Therefore the LTTE was not happy with the peace talks. 45 “The discussions were merely the modalities for the talks and were not leading to a solution. Observers have claimed that both parties were pushed to the talks due to the risk of losing huge amounts of international aid.”49 Sumanasiri Liyanage points out four objectives of the LTTE to participate in the peace talks. First, to gain international recognition again, leading to the revocation of the ban as a terrorist organization in the UK, USA, Canada, India and Australia. Second, to gain access to the areas controlled by the government in Jaffna under the MoU. Third, to have free movement at sea, and fourth, to gain control of the rehabilitation process in the Northern and Eastern provinces.50On the other hand, there were many critics of the peace talks, who saw it as not supporting reconciliation or a long lasting peace in the country. For instance, a tentative control of the LTTE in the North-East would conflict with the interests of the Muslim and Sinhalese people who lived in the Eastern Province.51 Likewise, there were growing objections in the South about the sincerity and transparency of Norway‟s role as a facilitator in the peace process.52As a facilitator, Norway had appeared to pay more attention to the Tamil interests rather than play an impartial role with the other ethnic interests in the country.53 For instance, the Muslims and the anti-LTTE Tamil groups were not happy with the decision of Norway to view the LTTE as the sole representative of the Tamils and also they were not recognised in the ceasefire process. Further, there was growing protest on demarcating the territory of Sri Lanka into a LTTE controlled area and a government controlled area; this was criticized by several groups as it had the effect of undermining the territorial integrity of the 49 G. Samaranayake (2005) op cit, p. 57 Sumanasiri Liyanage, "What Went Wrong." Polity 1, no. 3 (2003): 16-27. 51 Neville Laduwahetty. Sri Lanka's National Question. (Colombo: VijithaYapa, 2010). P. 180 52 President Rajapaksa stated in his election campaign of 2014 that he had some issues regarding the impartiality of Norway‟s role in the peace process. 53 See Neville Laduwahetty (2010) op cit. 50 country.54In addition, Norway played a dual role as the facilitator for the talks on one hand and as head of the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission on the other hand. These hybrid roles were criticized as being incompatible with Norway‟s position as a neutral actor in the peace process. (7) The Post-Tsunami Operational Management Structure (2005) The post-tsunami period created a valuable opportunity to achieve peace in some conflict affected countries. Unfortunately, it did not create the same opportunity in the case of Sri Lanka.55The Tsunami wave hit Sri Lanka on the 26thof December 2004, causing heavy damages to the coastal areas in the Northern as well as the Southern parts of the country. This natural disaster posed a huge challenge to the government in connection with providing humanitarian relief and reconstructing the devastated areas. To fulfil this task the government signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the LTTE to establish an operational mechanism for relief and reconstruction activities in the Tsunami affected areas of the North and the East. Both the government and the LTTE agreed to establish a Post – Tsunami Operational Management Structure (P-TOMS) and signed the MoU in March 2005.56 After the MoU was signed the members of parliament of the “Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna” (JVP) filed a petition, challenging the signing of the MoU between the 54 See LLRC Report, (Colombo: Government of Sri Lanka, 2011) In Aceh in the post-tsunami era, the conflicted parties gave up violence and were serious about seeking a negotiated solution to the protracted ethnic issue. See,Kamarulzaman Askandar. "The Aceh Conflict and the Roles of Civil Society." In Building Peace: Reflections from Southeast Asia, edited by Kamarulzaman Askandar.(Penang: SEACSN, 2005); Felix Heiduk.Serious of Country Related Conflict Analysis: Province of Aceh/Indonesia. (Berlin: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2006); The World Bank. The Conflict Recovery in Aceh (Washington DC: The World Bank, 2005) 56 The P-TOMS management structure consisted of three levels, high level committee, regional committee and the district committees. Regional committee was the most powerful body and would be responsible for the implementation and management of the development projects and the relief services. 55 government and the LTTE. The petition challenged the MoU on several grounds.57 The Supreme Court decided that the P-TOMS should be re-established after making certain amendments to the MoU.58 However, the government was not interested in making any amendments to the MoU and so the tsunami peace mechanism was abandoned in Sri Lanka. In April 2004, a new general election was held and the United People‟s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) established a new government headed by the Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa. Soon after this, Mahinda Rajapaksa won the presidential election too, held in November 2005.The new President‟s initial approach to the conflict in the country was based on a negotiated settlement that would establish a long lasting peace.59 (8) Resumption of Peace Talks (2005-2006) President Mahinda Rajapaksawas sworn in as the 5th executive President of Sri Lanka in November 2005. Soon, he restarted the stalled talks with the LTTE as Norway was ready to continue facilitating the peace talks. There were three rounds of peace talks, the first in Geneva in February 2006,the second in Oslo in June 2006 and the third one in Geneva again, in October 2006.60Although the LTTE delegation flew to Oslo for negotiations in June 2006, they refused to continue the talks after stating that they were not satisfied with the composition of the government delegation. In the last round in October 2006, the LTTE had once again refused to proceed with the peace talks with the Sri Lankan delegation until the government 57 The JVP argued that the government has no power to vest financial control to a militant group. See R. Edirisinghe et al., (2008) op cit. 58 Ibid. 59 See Mahinda Chintana, Election manifesto of UPFA for the presidential election in 2005. 60 This is the 5th attempt at peace talks between the government and the LTTE. agreed to meet certain conditions.61 However, during the ceasefire the LTTE had violated the CFA 3,830 times compared with just 351 violations by the government security forces.62The resumption of peace talks by the two parties collapsed with the developing mistrust between them; finally, the government announced that it was not going to proceed with the peace negotiations because of the growing number of violent activities carried out by the LTTE throughout the country. 63Thus, the last attempt at holding peace talks with the LTTE was in October 2006. So, in the history of the conflict in Sri Lanka, a peaceful outcome could not be realized throughout the 30 years of separatist struggle. Due to the negative attitude shown by the LTTE for peaceful negotiations, which was apparent throughout the conflict, the government could justifiably claim that the LTTE did not have a positive attitude toward peaceful power devolution. Rather, their objective was to implement their political agenda by fair means or foul, and work for a separate state for the Tamils.64As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the Eelam War IV created the background for the government to launch extensive military operations to fight the LTTE as a permanent solution to end their terror activities and restore peace in the country. (9) Conclusion To sum up the root causes of the polarization of the Sinhala – Tamil political relations, it is necessary to examine the changes that took place in the political, 61 The LTTE refused to participate in peace talks until GOSL agreed to open the A-9 highway from Kandy to Jaffna. 62 The LTTE committed several human rights violations during the ceasefire agreement. For instance, a number of children had been abducted and later recruited as child solders. Further expansions of LTTE military bases, collecting of weapons, attacking the navy etc. were reported. See Humanitarian Operation Factual analysis (2011) p. 40 63 See ibid. 64 The LTTE strongly believed that they could easily reach their goal of a separate state with the help of their military strength and the support of the diaspora. Violations of ceasefire agreements compelled the government to restart military operations repeatedly. See C.A. Chandraprema, Gota’s War: The Crushing of Tamil Tiger Terrorism in Sri Lanka, (Colombo: Authors publication, 2013) economic and social spheres since the country‟s independence. Some of these changes acted as the root causes that directly influenced the demand for a broad power devolution model for the Tamil majority areas in the country. In this sense, demanding a federal system can be identified as the dominant root cause of the conflict, which transformed into the demand for a separate Tamil homeland. The Tamil demand for a separate Tamil homeland in the Northern and the Eastern provinces of Sri Lanka later transformed into a protracted war. This political agitation for Eelam had created a strong division within the ethno-political relations in Sri Lanka. The government, both by itself and with the assistance of the international community, made several attempts to find a peaceful political solution. The following table (Table 3.5) shows a summary of the peace negotiations that took place between the government and the Tamil groups during the conflicted period. It is a significant matter that the peace making attempts were not successful and gradually both parties moved towards physical confrontation. This chapter revealed the jeopardizing of the peace process that was caused by several factors. First, it must be mentioned that highly nationalistic movements on both sides have proved to be very obstructive of any solution that aimed for a fair and satisfactory outcome to the conflict. The fear of broad power devolution on the part of the Sinhalese and the aim of a separate state by the LTTE had worked against a reasonable power devolution package. Although the LTTE participated in negotiations for political power devolution it was clear that the LTTE would not be satisfied by any solution other than their ultimate aim of the separate state. This was proved by the continuous violent activities of the LTTE, which proved highly detrimental to the national security of Sri Lanka. In other words, the LTTE believed in the use of terror activities such as bomb blasts, shootings and attacks against living and material targets rather than depend on a peaceful negotiated settlement. This was further underlined when a number of foreign countries banned the LTTE as a terrorist organization. On the other side, the government‟s progressive attempts to resolve the ethnic conflict were viewed with suspicion by the extreme nationalist groups within the majority Sinhalese population. The Sinhalese nationalist political parties such as the MEP, JVP and the JHU were absolutely unwilling to depart from the unitary model of the country as enshrined in the past and present constitutions of Sri Lanka. Further, this paper discussed the two attempts made to reach a negotiated solution, first with the help of India and then with Norwegian assistance. The IndiaLanka peace accord implemented the provincial council system but this did not achieve a long lasting solution to the conflict since both the LTTE and some groups among the Sinhalese and the Muslims were not agreeable to this. The Indian solution was directly applied to Sri Lanka as a top down solution by the Indian government but without the consent of the stakeholders of the conflict. This was the major shortcoming of the Indian mediation. The second attempt made by the Norwegians did not deliver satisfactory results either. The ceasefire agreement that was signed and the related agenda for solutions were made without consulting the parliament of Sri Lanka and other stakeholders. This was the main failure of the process that Norway tried to carry through. Further, as mentioned above, the LTTE was not at all sincere about a peaceful solution, and in fact was secretly organising for war during the ceasefire agreement. The following table (Table 01) shows the attempts and the outcome of peace process in Sri Lanka from its beginning. Table: 01 The peace negotiations in Sri Lanka (from 1995 to 2008)- by Thalpawila. The Attempts for Peace in Sri Lanka 1.Thimphu Talks between GOSL, Tamil political parties, and the Tamil militant groups in 1995. 2. Indo – Sri Lanka Peace Accord in 1987. Signed by India and Sri Lanka. 3. Cross Party Select Committee in 1991. The political parties of the parliament and the Tamil political parties in Sri Lanka. 4. The peace negotiations between GOSL and the LTTE between 19942002 5. Norwegian facilitated peace process 2002-2008. 6. Post -Tsunami operational management structure in 2005. The Outcome of the Attempt The GOSL rejected the Tamil demands on rights of Tamil self-determination and integrity of the Tamil homeland. The GOSL decentralized the power on provincial basis and established the provincial councils. The LTTE resisted the peace accord and provincial councils. The report recommended an “Apex Council” as the unit of devolution. The Tamil political parties rejected the proposals. The opposition parties rejected the draft of the constitution of the government. The draft consisted of wider power devolution in a unitary state of Sri Lanka. The LTTE‟s proposal was resisted by the Sinhalese majority. The LTTE violated the cease fire agreement on a large scale. The JVP challenged the P-TOMS proposal in court. The government then abandoned the proposal. Hence, this chapter has presented a number of reasons for the failure of peace talks and the continuation of war in Sri Lanka and the reasons that forced the government to settle for a military solution to bring an end to the war and restore peace. View publication stats