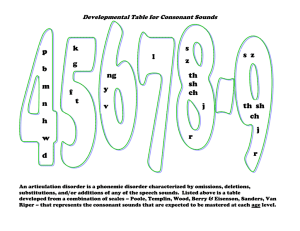

In Partial Fulfillment of the Subject Requirement for ELT 4006 THE READING INSTRUCITON READING INTERVENTION PROGRAM (on Phonemic Awareness) Submitted to MRS. JANET A. MANANAY, Ed. D. By: KAYLE BORROMEO June 2022 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. RATIONALE …………………………………………………………………………..….….1 II. READING THEORIES AND PRINCIPLES …………………………………..…….……3 III. INTERVENTION PROGRAM DETAILS ……………………………………………….6 IV. IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ……………………….…………………………………….10 V. BUDGETARY AND RESOURCE REQUIREMENTS ……………………………….....12 VI. ASSESSMENT MECHANISM ………………………..……………………………….....12 REFERENCES ……………………………………………...……………………………….....13 I. RATIONALE As adults, reading comes off to us as a straightforward task but the process behind it is actually complex. It is not a natural part of the human cognitive development so it needs to be taught for it to be learned. For beginner readers, learning to read is particularly a challenge to undertake because reading involves many skills which need to be developed systematically. To learn to read, children must develop both fluent word reading and language comprehension (Gough & Tunmer, 1986). Fluent word reading stems from underlying skills: phonological awareness, phonics and decoding, and automatic word recognition. Further, the National Reading Panel (NRP) has developed a list of the early reading skills called “The 5 Pillars of Reading”, namely the Phonemic Awareness, Phonics Instruction, Fluence Instruction, Vocabulary Instruction, and Comprehension Instruction. These skills develop in a hierarchical manner, with the ability to complete some skills necessarily preceding others. As such, it is paramount that beginning readers must master phonemic awareness, being the first pillar of reading instruction, as it is the basis for word reading and, eventually, comprehension. Phonemic awareness is a subset of phonological awareness focusing just on the smallest units of sound in human speech. It relates to the ability to hear and identify individual phonemes. Early exposure to sounds and letters is critical, even before school begins (Richards, 2009; Tallal, 2012). As early as that, children must be aware of four things: (i) speech is composed of the smallest meaningful units of sounds (phonemes); (2) letters (graphemes) and word parts (morphemes) are visual language symbols; (3) written letters represent the sounds (alphabetic principle); and (4) phonemes and morphemes can be manipulated (segmenting and blending). This is what phonemic awareness is all about. Phonemic awareness is important as it cues beginning readers that letters are represented by sounds which can prepare them for reading printed materials and gives them a way to approach sounding out and reading new words Many experimental studies have evaluated the effectiveness phonemic awareness instruction in facilitating reading acquisition. As Kame’enui, et. al., 1997 states, "One of the most compelling and well-established findings in the research on beginning reading is the important relationship between phonemic awareness and reading acquisition." Research indicates that phonemic awareness and letter knowledge are key predictors to students’ success in learning to read (National Reading Panel, 2000). In fact, predictive studies show that when children enter kindergarten with the ability to manipulate phonemes and identify letters, they progress at a faster pace in learning to read (Ehri & Roberts, 2006). Readers must have awareness of the speech sounds that letters and letter combinations represent in order to move from a printed word to a spoken word (reading), or a spoken word to a written word (spelling) (Moats, 2010). Awareness of the sounds in spoken language is required to learn letter-sound correspondences; to blend sounds together to decode a word; and to "map" words into long-term sight vocabulary (Kilpatrick, 2015). Citing multiple research studies, Bryant ­­et al (2014: 211) note the strong “connection between young children’s awareness of phonological segments, particularly of phonemes, and their progress in learning to read” (Badian, 1994; Bradley & Bryant, 1983; Cardoso-Martins & Pennington, 2004; de Jong & van der Leij, 1999; Ehri et al., 2001; Muter & Snowling, 1998; Parrila, Kirby, & McQuarrie, 2004). Many other studies consistently confirm that phonemic awareness along with letter recognition are the two best early predictors of reading success, and more recent studies have demonstrated that phonemic awareness skills influence children’s 1 broader academic success throughout most of their schooling (Blomert & Csépe, 2012; Bryant et al, 2014; Vaessen & Blomert, 2010). Results are claimed to be positive and to provide a scientific basis documenting the efficacy of PA instruction. However, it is a challenge because there are 26 letters in the English alphabet and there are more than 40 phonemes as some letters have more than one sound, e.g., the sound of letter ‘a’ in the words cab and cake. Further, some letters form a completely new sound when they are put together, such as ‘th’ in the word the or ‘ch’ in the word chat. As such, it is no wonder why it is difficult or confusing for beginning readers. Associate Professor in the Department of Elementary and Bilingual Education at California State University Hallie, Kay Yopp (1992), author of “Developing Phonemic Awareness in Young Children”, says the aspect of language children are missing is phonemic awareness. Yopp (1992) focuses on the missing element of phonemic awareness surrounding young children. One major facet presented by Yopp (1992) explains the unawareness children have involving the makeup (sounds and phonemes) of words. Although Yopp (1992) proves her reiteration of the implementation of phonemic awareness, she says that the nature of phonemes is difficult for children to notice. Yopp (1992) concludes in saying phonemes and sounds are instrumental aspects to the improvement of oral language among children, however, phonemes are discrete abstract units of speech that can be difficult to understand. Further, Blachman (2000) states that students with strong phonological awareness are likely to become good readers, but students with weak phonological skills will likely become poor readers and that it is estimated (Blachman, 1995) that the vast majority—more than 90 percent— of students with significant reading problems have a core deficit in their ability to process phonological information. Phonemic awareness performance is a strong predictor of long-term reading and spelling success (Put Reading First, 1998) as it is the base for strong reader, and is an important part of reading intervention. Intervention is necessary when children do not make adequate progress with phonological skills even after receiving strong core instruction with opportunities to practice. Children with phonological difficulties benefit from intensive practice with phonological awareness; practice associating phonemes (sounds) to spelling patterns; and practice decoding words (Snowling, 2013). Using effective strategies for phonemic awareness instruction is a must when helping struggling readers. 2 II. READING THEORIES AND PRINCIPLES This Reading Intervention Program uses traditional reading theories and models which are relevant to beginning readers to aid the difficulties and challenges they face in phonemic awareness. Traditional theories of reading suggest it is a process by which individuals learn smaller, discrete words and parts of words before learning how to read whole sentences, paragraphs and so on. Traditional theories of reading maintain that individuals build up their vocabularies and grammatical rules, and through this act of accretion they slowly gather together the necessary components to read fluently. These bottom-up theories of reading lend themselves to models of instruction such as phonics-based learning, in which individuals sound out phonemes or parts of words and slowly combine them into whole words, whole words into sentences, and so on. Bottom-Up Theory While there are many theories about how to teach reading, the bottom-up theory is used widely worldwide due to the sequential approach it has. This theory involves explicit and direct instruction in a building-block approach using the 5 components of reading during early childhood education: Phonics (Understanding the sounds that correspond with the letters of the alphabet, including short and long vowels. It also involves connecting the idea that letters correspond with sounds and those sounds make words.); Phonemic Awareness (Understanding the sounds that correspond with the letters of the alphabet, including short and long vowels. It also involves connecting the idea that letters correspond with sounds and those sounds make words.); Vocabulary (Understanding the sounds that correspond with the letters of the alphabet, including short and long vowels. It also involves connecting the idea that letters correspond with sounds and those sounds make words.); Fluency (The understanding of the meaning of words and how to use them appropriately and adequately in sentences.); and Comprehension (The capacity to recall characters, events, and the main concept of the passage or story once read, understanding what has been read correctly.). Reading activities in the bottom-up theory include students learning to read from the bottom (foundation) up to concepts like phonics and phonemic awareness. This means that children are first taught the basics to develop the basic, foundational skills needed for mastery of reading and are then advanced to learning vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. To elaborate, Gough (1972) proposes a phonics-based or bottom-up model of the reading process which portrays processing in reading as proceeding in serial fashion, from letter to sound, to words, to meaning, in the progression suggested in the accompanying figure: 3 Stated in Gough's terms the reading system, from a bottom-up perspective, functions in sequences as follows. First, the graphemic information enters through the visual system and is transformed at the first level from a letter character to a sound, that is, from a graphemic representation to a phonemic representation. Second, the phonemic representation is converted, at level two, into a word. The meaning units or words then pass on to the third level and meaning is assimilated into the knowledge system. Input is thus transformed from low-level sensory information to meaning through a series of successively higher-level encodings, with information flow that is entirely bottom-up, no higher-level processing having influence on any lower-level processing. This process is also referred to as data-driven. According to Browne (1998), this model describes reading as a process that starts with the learner’s knowledge of letters, sounds and words and how these words are formed to make sentences. This model is called part to whole model because it goes from partial to whole knowledge. This model is so effective in the early childhood, especially students as young learners. It’s effective because the emphasis here is on the letters, recognition of their shapes and reading individual words. Synthetic Phonics Synthetic phonics is a method of teaching where words are broken up into the smallest units of sound (phonemes). Readers learn to make connections between the letters of written texts (graphemes or letter symbols) and the sounds of spoken language. Synthetic phonics also teaches how to identify all the phonemes in a word and match them to a letter in order to be able to spell correctly. In other words, readers are taught how to break up words, or decode them, into individual sounds, and then blend all the way through the word. As mentioned earlier, the English language has 26 letters but 44 unique sounds, each with lots of different ways to spell them. A synthetic phonics approach will teach these 44 sounds from the simple to the more complicated logic. Readers are first taught that each alphabet letter has its own unique sound. Once readers have this concept, the logic is made a little harder. Two (or sometimes three) letters can also come together to make a new sound (e.g., “sh”, “ch”, “th”), that a sound can be represented in many ways (e.g., the sound /ee/ can be represented by /ea/, /e/, /ee/), and that a letter or group of letters can represent different sounds (e.g., the sound of “e” in the words “bed” and “she”). As soon as children have learned between 6-8 alphabet sounds, they must 4 start blending to read words. The process of reading involves decoding or ‘breaking’ words into separate sounds, which can then be blended together to read an unknown word. Spelling, then, will be taught alongside with reading by counting the sounds in a word and representing each sound with a letter. Lastly, what the readers have learned must be practiced with decodable texts. The ability to think about words as a sequence of phonemes is essential to learning how to read an alphabetic language. Readers should become aware of the building blocks of spoken language. They need to understand that sentences are made up of strings of separate words. They should become comfortable in hearing and creating rhymes. They should be led to play with the sounds of language until they can pull words apart into syllables, and pull syllables into individual phonemes. Given a comfortable familiarity with letters and an awareness of the sounds of phonemes, readers are ready to learn about letter-sound correspondence. The most important goal at this first stage is to help children understand that the logic of the alphabetic writing system is built on these correspondences. As readers learn specific letter-sound correspondences, they should be challenged to use this knowledge to sound out new words in reading and writing. Making a habit of sounding out unfamiliar words contributes strongly to reading growth, not just for beginners, but for all readers. Readers need to understand that sounding out new words can actually be a strategy for helping them unlock pronunciations of words they have never seen before, and can make what they are reading understandable. 5 III. INTERVENTION PROGRAM DETAILS Phonemes are the units of speech that are represented by the letters of the alphabetic language. Many children know their letter sounds, but cannot recognize these sounds when sounding out words. Thus, developing readers must learn to separate these sounds, one from another, and to categorize them in a way that permits understanding how words are spelled. It is this sort of explicit, reflective knowledge that falls under the rubric of phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is the ability to notice, think about, and work with the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. Manipulating the sounds in words includes blending, stretching, or otherwise changing words. Children can demonstrate phonemic awareness in several ways, including: • • • • recognizing which words in a set of words begin with the same sound ("dog, doll, and dance all have /d/ at the beginning.") isolating and saying the first or last sound in a word ("The beginning sound of dog is /d/." "The ending sound of dog is /g/.") combining, or blending the separate sounds in a word to say the word ("/m/, /a/, /p/ – map.") breaking, or segmenting a word into its separate sounds ("up – /u/, /p/.") Children who have poorly developed phonemic awareness at the end of kindergarten are likely to become poor readers. Explicit instruction in sound identification, matching, segmentation, and blending, when linked appropriately to sound-symbol association, reduces the risk of reading failure and accelerates early reading and spelling acquisition for all children. Teaching these skills well, however, is not as easy as it might seem. Teachers must themselves be aware of speech sounds and how they differ from letters in order to help students acquire awareness of phonemes and the symbols that represent them. In addition, teachers need to understand the developmental progression from spoken word and syllable identification to blending and segmenting all the phonemes in simple words. The design and sequence of activities in this reading intervention program are intended to help children acquire a sense of the architecture of their language and the nature of its building blocks. Instructions in this phase begin with auditory-verbal exercises to direct children's attention to sound, but phonemes should be linked with letters once children understand that letters represent segments of their own speech. As the children practice synthesizing words from phonemes and analyzing phonemes from words, they are also practicing hearing and saying the phonemes over and over, both in isolation and in context. They are becoming generally familiar with how the different phonemes sound and how they are articulated. They are becoming comfortable with hearing and feeling the identity and distinguishing characteristics of each phoneme, whether spoken in isolation or in the beginning, middle, or end of a variety of words. Research shows that once children have mastered phonemic awareness in this way, useful knowledge of the alphabetic principle generally follows with remarkable ease — and no wonder: Having learned to attend to and think about the structure of language in this way, the alphabetic principle makes sense. All that's left to make it usable is knowledge of the particular letters by which each sound is represented. 6 Initial Sound Match Instructions for administration: • • • Tell student three words (two that have the same initial sound and one that does not). Ask student to identify which two words have the same initial sound. Increase up to three (3) and then four (4) words and have the student tell which two words have the same initial sound. Initial Sound Identification (with picture cards) Materials: Picture Cards Instructions for administration: • • • Show student three picture cards or picture tiles (two that begin with the same sound and one that does not). Ask student to identify which two pictures have the same initial sound by asking student to remove the card that does not have the same initial sound. Increase up to five (5) or six (6) cards and have the student remove all the words that do not have the same initial sound (only two cards will remain). Initial Sound Production (with picture cards) Materials: Picture cards Instructions for administration: • Show student various picture cards. Ask the child to produce the initial sound of the object in the picture. Begin with more simple initial consonants and then progress in the following order. ▪ Consonants (mat, can) ▪ Short vowel sounds (egg, ant) ▪ Consonant blends (black, frog) ▪ Consonant digraphs (shop, chin) ▪ Long vowel sounds (eat, aim) Final Sound Identification Instructions for administration: • • • Tell student three words (two that have the same final sound and one that does not). Ask student to identify which two words have the same final sound. Increase up to three (3) and then four (4) words and have the student tell which two words have the same final sound. 7 Final Sound Identification (with picture cards) Materials: Picture cards Instructions for administration: • • • Show student three picture cards or picture tiles (two that end with the same sound and one that does not). Ask student to identify which two pictures have the same final sound by asking student to remove the card that does not have the same final sound. Increase up to (five) 5 or (six) 6 cards and have the student remove all the words that do not have the same final sound (only two cards will remain). Final Sound Production (with picture cards) Materials: Picture cards Instructions for administration: • Show student various picture cards or picture tiles. Ask the child to produce the final sound of the object pictured. Begin with more simple final consonants and then progress in the following order. ▪ Consonants (mat, can) ▪ Consonant digraphs (touch, cash) ▪ Long vowel sounds (tea, be) 8 Medial Sound Identification Instructions for administration: • • • Tell student three words (two that have the same medial sound and one that does not). Ask student to identify which two words have the same medial sound. Increase up to three (3) and then four (4) words and have the student tell which two words have the same medial sound. Medial Sound Identification (with picture cards) Materials: Picture cards Instructions for administration: • • • Show student three picture cards or picture tiles (two that end have the same medial sound and one that does not). Ask student to identify which two pictures have the same medial sound by asking student to remove the card that does not have the same final sound. Increase up to 5 or 6 cards and have the student remove all the words that do not have the same medial sound (only two cards will remain). Medial Sound Production (with picture cards) Materials: Picture cards Instructions for administration: • Show student various picture cards or picture tiles. Ask student to produce the medial sound of the object pictured. Begin with more simple medial consonants and then progress in the following order. ▪ short vowel sounds (cat, pin) ▪ long vowel sounds (team, time) 9 IV. IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Challenges/ Difficulties Target learners and justification Theory/ Model/ Approach used Details Duration Beginning readers know the sounds but have trouble recognizing the sounds when sounding out words. Beginning Readers who are in Kinder 2 to Grade 1 are selected as this reading intervention’s target learners as it is the level when formal reading programs are offered in most schools. These learners have already acquired initial knowledge on the letters of the English alphabet and its corresponding sounds. Learners who are facing this difficulty need to receive more foundational knowledge on phonological awareness, specifically phonemic awareness, to be able to move onto the higher skills like phonics and fluency. Bottom-up Model of Reading In this intervention, students will receive more instruction and activities on identifying and producing sounds whether it is used at the beginning, middle, or end of the word. 20-30 minutes for 4-5 days for three succeeding weeks but this is best determined by the needs of the learner Week 1 Day 1 Intervention Instruction Initial Sound Match Day 2 Conduct a brief review on the previous’ day intervention activities. Day 3 Conduct a brief review on the previous’ day intervention activities. Initial Sound Identification (with picture cards) Initial Sound Production (with picture cards) Day 4 Summarize all the intervention activities done on the previous days. Day 5 Provide activities for students to apply/ synthesize their intervention learnings. 10 Week 2 Day 1 Final Sound Match Intervention Instruction Day 2 Conduct a brief review on the previous’ day intervention activities. Day 3 Conduct a brief review on the previous’ day intervention activities. Final Sound Identification (with picture cards) Final Sound Production (with picture cards) Day 2 Conduct a brief review on the previous’ day intervention activities. Day 3 Conduct a brief review on the previous’ day intervention activities. Medial Sound Identification (with picture cards) Medial Sound Production (with picture cards) Day 4 Summarize all the intervention activities done on the previous days. Day 5 Provide activities for students to apply/ synthesize their intervention learnings. Day 4 Summarize all the intervention activities done on the previous days. Day 5 Provide activities for students to apply/ synthesize their intervention learnings. Week 3 Day 1 Medial Sound Match Intervention Instruction 11 V. BUDGETARY AND RESOURCE REQUIREMENTS This Reading Intervention Program does not require much budget allocation for its implementation. Although investing on materials is always a good idea, the materials required for this intervention does not require for schools to spend. Teachers can look for available images on the internet and have it printed or they may use images taken from magazines, newspaper, old books, etc. VI. ASSESSMENT MECHANISM Classroom instruction and early interventions (Kindergarten and Grade 1) are key to preventing future word-reading difficulties. These students should receive intensive intervention and their progress should be monitored. Based on their progress, students may (1) need more intensive intervention, or (2) continue to need the current amount of intervention, or (3) discontinue their current intervention. In assessing the effectivity of this intervention, teachers may use the following approaches: • • • Comparing pre- and post-intervention book-reading levels Assessing whether students improved on one or more measures, sometimes specific to the intervention program Comparing students’ improvement in an intervention program with a group of students who did not have the intervention. Screening and progress monitoring help determine the level or intensity of intervention needed. All students should be screened throughout the early years to identify who is not developing the required foundational word-reading skills, despite evidence-based instruction. 12 REFERENCES Blachman, B. A. (1995). Identifying the core linguistic deficits and the critical conditions for early intervention with children with reading disabilities. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Learning Disabilities Association, Orlando, FL, March 1995. Blachman, B. A. (2000). Phonological awareness. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Rosenthal, P. D. Pearson, and R. Barr (eds.), Handbook of reading research, 3, pp. 483-502. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Blomert, L., & Cs epe, V. (2012). Psychological foundations of reading acquisition and assessment. In B. Csapo & V. Csépe (Eds.), Framework for diagnostic assessment of reading (pp. 17–78). Budapest, Hungary: Nemzeti Tanko€nyvkiado. Browne, Ann (1998) A Practical Guide to Teaching Reading in the Early Years. London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd. p. 9 Bryant, P., Nunes, T., & Barros, R. (2014). The connection between children's knowledge and use of grapho‐phonic and morphemic units in written text and their learning at school. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84 (2), 211-225. Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z. and Shanahan, T. (2001), Phonemic Awareness Instruction Helps Children Learn to Read: Evidence From the National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 250–287. doi:10.1598/RRQ.36.3.2 Ehri, L., & Roberts, T. (2006). The roots of learning to read and write: Acquisition of letters and phonemic awareness. In D. Dickinson & S. Neuman (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 2, pp. 113–130). New York: Guilford. Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6–10. Kame'enui, E.J., Simmons, D.C., Baker, s., Chard, D.J., Dickson, S.V., Gunn, B., Smith S.B., Sprick, M., & Lin, S.J. (1997). Effective strategies for teaching beginning reading. In E.J. Kame'enui & D.W. Carnine (Eds.). Effective Teaching Strategies That Accommodate Diverse Learners. Columbus, OH: Merill. Kilpatrick, D. (2015). Essentials of assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties (Essentials of psychological assessment). Boston: John Wiley and Sons. Moats, L, & Tolman, C (2009). Excerpted from Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS): The Speech Sounds of English: Phonetics, Phonology, and Phoneme Awareness (Module 2). Boston: Sopris West. 13 National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read. Washington, DC: National Institute of Health and Human Development. Snowling M. J. (2013). Early identification and interventions for dyslexia: a contemporary view. Journal of research in special educational needs: JORSEN, 13(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2012.01262.x Vaessen, A., & Blomert, L. (2010). Long-term cognitive dynamics of fluent reading development. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 105(3), 213–231. Yopp, H. K. (1995). A Test for Assessing Phonemic Awareness in Young Children. The Reading Teacher, 49(1), 20-30. doi:10.1598/rt.49.1.3 14