HPRIN COUNTY FREE LIBRARY

31111009994219

:*

J

i

%<¥ *k

TWAYNES ftUSTKRVYORk STUDIES

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011

http://www.archive.org/details/scarletletterreaOObaym

r

CIVIC

CENTER

3 1111 00999 4219

DATE DUE

WAV?

p»R

4 1989

OCT 18 1989

,,

.

,-ttiO

,

OCT l?

1990

'."

'

DEC

ff-

'

't

t

isi»d

I

om1

So

n

h.

3

«aa

T99j

~

a nn

APR

n

MM

9 £ JUI

flO.

*/ib/o^

F

1

TWAYNE'S MASTERWORK STUDIES

Robert Lecker, General Editor

The

Bible:

A

Literary Study

John H. Gottcent

Moby-Dick: Ishmael's Mighty Book

Kerry McSweeney

THE

C A R L E T

s

T T

L E

A

E R

Read

L

]

i

n g

SINA BAYM

m

TWAYNE PUBLISHERS BOSTON

A Division of G. K. Hell & Co

«

1

The

Scarlet Letter:

A Reading

Nina Baym

Twaynes Masterwork

No.

Copyright

©

Studies

I

& Co.

1986 by G. K. Hall

All Rights Reserved

Published by Tivayne Publishers

A

Division of G. K. Hall

70 Lincoln

All quotations

Edition, vol.

1,

Street,

& Co.

Boston, Massachusetts 021

1

from The Scarlet Letter are taken from the Centenary

published by the Ohio State University Press, 1962. Letters

quoted in "The Critical Reception" are taken from volume 16 of the

Centenary Edition, Letters 1843-1853 (1985), 311-12 and 421.

Copyediting supervised by Lewis DeSimone

Designed and produced by Marne

Typeset

B. Sultz

10114 Sabon with Cloister

in

Display type by Compset, Inc.

Printed on permanent! durable acid-free paper

and bound

in the

United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Baym, Nina.

The scarlet letter.

(Twaynes masterwork studies

;

no.

1)

Bibliography: p. 109

Includes index.

1.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel, 1804-1864. Scarlet

I.

PS1868.B39

Title.

1986

II.

letter.

Series.

813' .3

ISBN 0-8057-7959-4

ISBN 0-8057-8001-7 (pbk)

86-9774

Contents

Chronology of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Life

The Historical Context

xiit

The Importance of The Scarlet Letter

The

Critical Reception

xxi

A READING

1.

WHAT? THE STORY

On

The

the threshold

plot thickens

'

A

'

1

story begins

Plot and structure

2.

WHERE? THE SETTING

The

historical setting

and

the symbolic

'

'

30

The marvelous

The

narrator

3.

WHO? THE CHARACTERS

The Puritans

Hester

'

'

Pearl

'

Dimmesdale

52

Chillingworth

'

Hawthorne

as psychologist

vii

xriii

4.

THE SCARLET LETTER

IN

THE SCARLET LETTER

83

5.

THEMES

IN

THE SCARLET LETTER

93

6.

THE SCARLET LETTER

AND "THE CUSTOM-HOUSE"

Bibliography of Selected Primary

Works

Bibliography of Selected Secondary

Index

About

the

114

Author

VI

101

116

Works

109

HI

Chronology of

Nathaniel Hawthorne's Life

1801 2 August:

In the

seaport town of Salem, Massachusetts, Nathaniel

Hathorne,

Sr.,

from

a seafaring family

himself, marries Elizabeth Clarke

and

Miriam Lord and Richard Manning, an up-

children of

and-coming merchant. The couple moves

orne's

a sea captain

Manning, one of nine

widowed mother and

Hawthorne,

Jr.,

added the

his

w

two

with Hath-

in

(Nathaniel

sisters.

to his family

name when

he began to publish.)

1802 7 March:

Manning Hathorne, their first

is away at sea.

Elizabeth

born

child,

while Nathaniel Hathorne

1804 4 July:

Nathaniel born. His father

is

away and does not

again

return until October, remaining in Salem only briefly.

1808 9 January:

A

third child,

is

at sea.

Surinam;

home

Maria Louisa, born. Nathaniel Hathorne

March: Hathorne,

in

about seven months

for

Hathorne returns

nings,

1813

among whom

to

of yellow fever, in

he has been at

life,

total.

July:

Elizabeth

to live with her natal family, the

her three children are to

Grandfather Manning

moves

Sr., dies

seven years of married

dies,

Man-

grow

up.

and Uncle Richard Manning

Raymond, Maine,

to

manage

family property

there.

1813-1815

A

foot injury

active play

this

is

slow to mend, keeping Nathaniel from

and friendships

time he develops

a

for

about two years. During

love for reading, especially storv

books.

1818

Elizabeth and the children

thaniel returns to

move

to

Raymond

Salem during winters

also.

but misses the wilderness and freedom of Maine.

vii

Na-

tor schooling,

THE SCARLET LETTER

1K21

Enters

Bowdoin College

his distress, his

1

825

1825-1837

in

mother and

Much

Brunswick, Maine.

sisters return to

to

Salem.

Graduates from college and returns to Salem. He has decided to

become

a writer.

Lives at

home

Salem

eral

in

(his

grandmother, as well as sev-

aunts and uncles, have died or

works

name and

New

of his

He changes

at his writing.

moved

out)

and

the spelling of his last

reads widely in contemporary periodicals and

England

which he uses

history,

most successful

stories.

this period,

he sends his

Athenaeum

to

as the basis for

Somewhat

sister

some

reclusive during

Elizabeth to the Salem

withdraw the books and magazines he

wants to read.

1828

Anonymous

publication of Fanshawe:

novel. In later

sister

1830-1837

Elizabeth

A

Tale, a short

he never mentions this work; only his

life

knows or remembers

that he wrote

it.

Begins to publish tales and sketches, anonymously,

in

periodicals.

1836

American Magaand Entertaining Knowledge, in an at-

Edits, with sister Elizabeth's help, the

zine of Useful

tempt to establish a

1837

literary career.

Writes, with sister Elizabeth's help, Peter Parleys Universal History, another attempt to support himself as a

literary

1837

man.

Brings out Twice-Told Tales, a selection from his previously published sketches and tales, under his

The book does not

sell

well but

it is

own name.

widely and favorably

reviewed. Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, a gregarious social

reformer and fellow Salemite, seeks him out and begins

to introduce

younger

1838

him

sister

to people in her circle, including her

Sophia.

Nathaniel and Sophia become secretly engaged. Begins

to publish in a

new

political journal, the

United States

Magazine and Democratic Review; most of

published

between

1838

and

1845

his

appears

in

work

this

magazine.

1839-1840

Financial security through literary projects having thus

tar failed

him, Hawthorne accepts a political appoint-

Chronology of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Life

ment, obtained through friends

as

1841

measurer of

salt

and coal

Democratic

in the

party,

Boston customhouse.

at the

Publishes Grandfather's Chair, a history, for children, of

New

England from the Puritan settlement through the

Revolution, which he had written while working at the

Boston customhouse. From April to November

the experimental

Brook Farm community

bury, Massachusetts,

discovers that he

is

lives at

West Rox-

hoping to find a way to sup-

still

without

himself

port

at

giving

up

his

goals;

literary

too exhausted and distracted to write

there.

1842 9

July:

Marries Sophia Peabody. Moves to Concord, Massachu-

where he

setts,

know major

movement

lives at the

figures

Old Manse and comes

to

American Transcendental

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Tho-

and Margaret

reau,

the

in

Fuller,

among

others.

expanded edition of Twice-Told Tales

as Biographical Stories for Children.

for periodicals, but

is still

He

A

second and

issued, as well

is

writes regularly

unable to make

a living as a

writer.

1844 March:

A

daughter, Una, born. Later in the year poverty forces

the family to break

his

1846 June:

A

up

who have moved

ents,

mother and

sisters in

son, Julian, born; a

and

tales,

briefly:

Sophia goes to her par-

to Boston; Nathaniel returns to

Salem.

new book

of collected sketches

Mosses from an Old Manse, published.

autumn

the family settles in Salem,

accepts

a

political

appointment

In the

where Hawthorne

as

surveyor

in

the

customhouse.

1849 June:

A new

from

administration dismisses Hawthorne

political

the

customhouse. July:

death

of

Hawthorne's

mother. September: begins to write The Scarlet Letter.

1850

Moves

to

Lenox, Massachusetts; meets and becomes

friends with

Herman

Melville and has considerable in-

fluence on the writing of

at the

end of the

lished by the

who

will

year.

Moby-Dick, which comes out

March: The

Scarlet Letter

Boston firm of Ticknor, Reed, and

is

pub-

Fields,

remain Hawthorne's American publishers for

the rest of his

life.

ix

THE SCARLET LETTER

1851

Moves

to

and

third

West Newton, Massachusetts. May: Rose,

last child,

Seven Gables

Twice-Told Tales

House of

born. Publishes The

of stories and sketches),

(a collection

and True Stories from History and Biography

set of biographies, for children, of

1

852

Moves

Book

for Girls

children),

and

second

Romance

(a

A Wonder-

novel),

and Boys (retellings of classical myths for

campaign biography of his college friend

a

Franklin Pierce,

States. July:

(a

famous people).

Concord, Massachusetts. Pub-

to the Wayside, in

The Blithedale

lishes

the

The Snow- 1 mage and Other

novel),

(a

who

elected president of the United

is

his sister

Maria Louisa

is

drowned

in

a

steamboat explosion.

1

853

consul

Pierce.

1853—1857

Tanglewood

Publishes

book of

classical

at

Tales for Girls

myths

Liverpool, England,

Has hopes

and Boys,

a

second

Appointed

retold for children.

by President Franklin

at last of being financially secure.

Lives in England during consular service. Keeps extensive

notebooks but finds

it

impossible to do any sus-

tained and publishable writing.

1857-1859

Pierce

is

not reelected, and Hawthorne's term as consul

He

ends.

lives in

Rome and

Marble Faun, which

ward

will

Florence, beginning

be his

the end of this period

last novel, in

Una becomes

with malaria and almost dies. The family

is

The

1858. To-

seriously

ill

permanently

affected by this near tragedy.

1859

After Una's recovery, the family returns to England,

where Hawthorne completes and publishes The Marble

Faun.

1860

Returns to the United States and the Wayside, which he

buys and remodels. The Marble Faun

is

published

in

the

of

fic-

United States.

1860-1864

Tries unsuccessfully to write another long

tion,

work

producing drafts and fragments of three different

romances.

He

also prepares

and publishes essays on Eng-

land drawn from notebook materials. His health begins

to

1863

fail.

Our Old Home, collecting his English essays, is pubHe dedicates the book to Franklin Pierce, an un-

lished.

Chronology of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Life

wise although loyal personal gesture

Civil

in the

War, when the Democratic party

is

midst of the

much out

of

favor in the North.

1864 19 May:

Dies

away from home while on

a brief vacation with

Franklin Pierce. Buried on 23 May.

xi

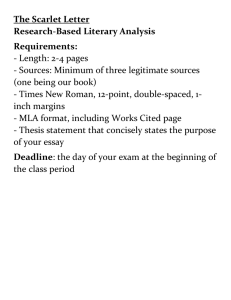

Nathaniel Hawthorne

1804-1864

Portrait by Charles

Courtesy of the Essex

Osgood,

I

X40

Institute, Sal.'m,

Mass.

The Historical Context

Viewed from one

thorne's adulthood

perspective, the nation during the years of

—

say,

from 1825 to

his death

—enjoyed

consensus and cultural harmony; viewed from another,

in

turbulence and conflict.

of the

same English or

the Mississippi River

towns

(in

On

it

Haw-

ideological

was mired

the one hand, Americans were mostly

Scottish ethnic background; they lived between

and the Atlantic Ocean on farms or

1840 only Baltimore, Philadelphia,

New

had populations above 100,000) sharing agrarian,

egalitarian values; they

in

small

York, and Boston

free-enterprise,

were passionately nationalistic

and

—protectionist

with respect to Europe, expansionist with respect to the American

continent.

hoped

ury.

If

few people were

for simple

rich,

few lived

in

deep poverty; most

comfort and material security rather than great lux-

They tempered

their individualism with strong

community

values;

they were optimistic believers in hard work, education, and the inevitable

On

connection between virtue, moderation, and success.

the other hand, Americans were divided between slave and free

states,

were engaged

continent's Native

massive relocation and extermination of the

in

American population, and were torn between an

economy based on ownership of land and one based on

money.

In

the 1840s reform

movements

community experiments sprang up

proliferated,

control of

and Utopian

across the nation, signs of social

malaise. Schisms within the established religious denominations, and

new

sects also

appeared

in

tional religious behavior

the established churches.

great numbers; evangelical and highly

emo-

began to replace the more sedate practices

The

of

political party structure, reflecting con-

Xlll

—

THE SCARLET LETTER

changed

stant realignment of interests,

in fifty years

from the opposi-

Democratic Republicans, to Whigs versus

tion of Federalists versus

Democrats, to Democrats versus Republicans (along with various

shorter-lived third parties); the

Democratic party evolved from the

money

"progressive" party of business and

to the "conservative" party

of landowners and slaveholders.

During Hawthorne's

were three wars

lifetime there

(the

War

of

1812, the Mexican War, and the Civil War), constant skirmishes in

and opponents of

the border states between defenders

and

slavery,

continual violence between settlers and Indians on the frontier. Severe

economic depressions

of

work and

sent

1815, 1837, and 1857 threw thousands out

in

numerous displaced farm

families into rapidly ex-

panding urban slums, there to mingle uncomfortably with newly

riving immigrants

Englanders especially

tive region for

to

new

left

lives

the

poor

and smallholdings of

soil

on the celebrated

frontier, all

moralistic approach to

ular

and cosmopolitan

intellectual

life,

life's

New

problems,

New

England, with

lost

York City

out to the

—

—one

by 1850

lishment of the Constitution

less

for

which

religious

and

much more

sec-

its

as the center of the nation's

while the South retreated ever more into

aratist culture. Already,

their na-

too often only

meet conditions of disease and extreme physical hardship

they were completely unprepared.

ar-

New

from Ireland, Germany, and Scandinavia.

its

own

sep-

than sixty years after the estab-

could hear, side by side with

expressions of the most intense national boosterism, the lament that

Americans had

lost their sense of national

the original values that

In the early years of the

nineteenth century,

a boy, the profession of authorship

underwent

England and America. Instead of being

men producing

purpose and had rejected

had made the country so promising.

a limited

number

when Hawthorne was

a dramatic

a matter of

change

in

educated gentle-

of expensive copies of their learned

writings for a small circle of like-minded subscribers, authorship took

on the shape that we know today: that of

the largest possible

profit, to

number

a business

designed to

sell

work

for

of mass-produced copies of a

anyone who could be persuaded

the result of increased literacy

and

to buy. This

phenomenon

leisure in the general population,

The

Historical Context

along with tremendous improvements and economies

facture

and distribution

—was greeted with mixed

in

book manu-

feelings

by the

lit-

erary establishment in England. But in America the idea of a nation of

readers accorded well with democratic aspirations.

During Haw-

thorne's youth, therefore, the profession of authorship

was being held

out by cultural leaders as a

way

and immense

to achieve fame, fortune,

two important

popularity while contributing to

patriotic enterprises:

enlightening the masses and establishing the United States as a nation

of culture and taste.

But as a profit-making business, publishing was

new masses

of readers than a follower, for

work, they wouldn't buy

like a

it.

if

The most

less a

leader of the

people didn't expect to

successful kinds of pub-

lication

became

or form

—types of writing that had never before been accorded high

the newspaper, the magazine, and fiction in any shape

status.

Fiction, indeed,

tan leaders,

had always been despised and condemned by

who saw

it

as dishonest

and

and

distracting;

it

Puri-

had also

been dismissed as useless by such Enlightenment figures as Benjamin

Franklin. Yet in the nineteenth century

the

American appetite

for fiction

it

appeared to observers that

had become simply

insatiable.

The

transformation of fiction from a despised genre to the favorite reading

of the day involved,

its

quality

creased.

among democratic Americans,

and value. As

From

fiction

a reassessment of

became more popular,

and 1820s, through the comic and melodramatic

Charles Dickens

of William

in

in the

1840s, novels (and fiction more generally) were

about human nature and

scribed as artists. But

great British writers?

society.

In

A dreamy and

better than

life,

For the

knowledge and wisdom

first

time, novelists were de-

where was the American novelist

to

match the

Hawthorne's youth only James Fenimore

Cooper seemed even remotely

Dickens.

ironic realism

the social protest fiction of Eliz-

increasingly accepted as major sources of

most

social novels of

the 1830s and 1840s, and then the

Makepeace Thackeray and

abeth Gaskell

prestige in-

its

the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott in the 1810s

a

candidate for a place beside Scott or

ambitious young man,

who

loved fiction

could indeed have fantasies of glory.

XV

al-

THE SCARLET LETTER

Nevertheless, American publishers, for

all

grand

their

were not

talk,

notably supportive of American writers. Since there was no international copyright,

was much cheaper

it

for

them

books from

to reprint

abroad than to pay royalties to American authors. During the very

years that

many were

sometimes as

if

loudly calling for a national literature,

it

seemed

publishers were supplying American readers with

works by writers of every nation except

their

own. Only

a handful of

highly popular writers managed, during Hawthorne's lifetime, to

make

a

good

through their writing, and they did so by being

living

extremely productive. The profession was not geared for authors

worked slowly and

carefully, or

whose

who

creativity alternated with long

periods of gestation.

Commonly,

imaginative writers would augment their

therefore,

earnings through editing or magazine journalism, or by political ap-

pointments. The poet William Cullen Bryant, for example, was chief

editor of the

in

New

York Evening Post for almost

fifty

years beginning

1829; Edgar Allan Poe worked as reviewer and editor for more than

a half

City;

dozen magazines

in

Charleston, Philadelphia, and

James Fenimore Cooper was the United

New

States consul at

from 1826 to 1833; Washington Irving held diplomatic posts

and England. And Nathaniel Hawthorne

pointments

at the

in his turn

was

in

York

Lyons

Spain

to hold ap-

Boston customhouse, the Salem customhouse, and

as United States consul in Liverpool.

Hawthorne began

his literary career writing short pieces,

which he

published anonymously in a variety of periodicals. "Secret" publication of this sort

was

quite usual, not because writing

was an

unacceptable profession, but because authors did not want their reputations tarnished by unpopular apprentice work.

ries

Not

until their sto-

had received favorable notice did they come forward

names, as Hawthorne did when he collected

1837 volume Twice-Told

Tales.

As

tales

a steady but

in their

and sketches

own

in the

slow worker, he did

not write a long piece of fiction before The Scarlet Letter, and

though

after that he

the

on

toll

planned to write long

his energies

was too great

fiction only, he

al-

found that

to sustain the pace of a novel

The

Historical Context

every year or every other year. Thus, he had to

making

a living

from

abandon

his

hope of

literature.

Appropriately, therefore, one can locate The Scarlet Letter in

as

Hawthorne's attempt to

realize the possibilities of authorship in a

country that accorded high status, but

writer; to blend the time-honored

entertain with

support, to a professional

little

power

of fiction to enchant and

newly recognized capacities for psychological and

its

social analysis;

day

its

and

to contribute to the national

life

by providing,

within the boundaries of a popular form, a thoughtful contemporary

examination of the Puritan heritage. In

point: secure in his creative

powers

his career

it

occupies a turning

after a long apprenticeship, he

turned from the safer, slighter short form to the challenges and

re-

wards of the novel.

The publication of The

Scarlet Letter inaugurated a period of con-

siderable productivity for

lished in the next

set in his native

two

Hawthorne, with two more novels pub-

years.

The House of

Salem but incorporating many characteristic elements

of the marvelous, dealt (as does

The

Scarlet Letter in a different fash-

ion) with the long-term effects of crime

Blithedale

eled

the Seven Gables (1851),

Romance

and

guilt

on two

families.

The

(1852) took place in a Utopian community mod-

on Brook Farm, chronicling the destruction of the reformers'

dreams and ambitions by

their

own human

shortcomings.

Hawthorne's acceptance of a consular appointment and

Europe had the unintended

The impact of Europe on

his

move

to

effect of terminating his literary career.

his consciousness

was exhilarating but

also

overwhelming, and consular duties along with sightseeing and family

responsibilities

absorbed

all

his energies.

His

last

completed novel,

The Marble Faun (1859), was another fantasy about

and

its

their effects

on history and the human psyche.

characters were

young American and

It

guilt

and crime,

was

set in Italy;

Italian artists.

When Hawthorne returned to the United States he felt displaced and

He had grown accustomed to life in Europe and was made

alienated.

uncomfortable by the war atmosphere that had transformed American

life.

He began work on

three different novels,

two of them dealing

THE SCARLET LETTER

with the return of an American of English descent to the old country,

a search for the "elixir of life," a drink that

and one about

would

confer immortality. Although his active literary career had essentially

ceased in

1

852, and although his only lukewarm support of the North

War

during the Civil

alienated the critics, he

death as Americas foremost

man

of

was acclaimed on

his

letters.

The Importance of The Scarlet Letter

When

thinking about what

we mean when we

we should remember

a masterpiece,

call a literary

work

that ultimately such judgments

do

not have absolute or objective validity, but depend on a cultural consensus, usually elaborated by those

what

it

means

—

—

a literary

author

work

is

one culture

work might

traces of individuality in a

for high praise; in another

specific

are specially trained, about

for literature to be "great." In

simple example

ture

who

is:

cul-

that cannot be identified as the creation of a

status.

tend to require for something called a literary masterwork

a display of great craftsmanship, indicating that the

net, ode, tragedy, or

and

it

immediately classified as the product of a "formula"

"mastered" the chosen medium, whether

adoxically

to give a

—notably our own, Western, modern

and dismissed from consideration for masterwork

What we

—

disqualify

comedy;

—transcends the

it is

striking originality,

rules of craft that the

us, the text

which

—almost par-

author has mastered;

clear traces of an individual sensibility in the

and probably more important to

author has

novel, short story, son-

work. Beyond

must make

this,

a powerful

emotional and intellectual impact, provide a rich reading experience,

and leave behind

perhaps a new

works we return

our past experience and

a larger understanding of

way

to think about our lives. In the case of the greatest

to

them time and again

in

our minds, even

not reread them frequently, as touchstones by which

world around

us.

of readers, by

The

These conditions have been

Scarlet Letter.

XVlll

we

if

we do

interpret the

satisfied, for

generations

—

The Importance of The

Literary

Every

skill.

critic

has acknowledged that

that

is

more

stately

command

and

less

plot

its

virtually perfect in

who

its

Scarlet Letter

has written about The Scarlet Letter

is

concisely elaborated in a structure

pacing and symmetry; and that

colloquial than

is

now

the

norm

style

its

—displays

a rich

of linguistic resources, including an extensive and precise

vocabulary, diverse sentence structure, modulations in tone, and a

from attention to the

striking variety of rhetorical devices ranging

sound of words on through complicated development of

speech, images, and symbols.

gain an enlarged sense of

and with the challenge of

Originality.

tell,

nor

into

it

is its

The

To read The

what

The

one does not have to read

treatment of the aftermath of adultery

original; those familiar with literary history will

precedented

in its

approach, and that

unconventional the work

the

way

is

know

extremely

it is

Those who are not experienced readers

tate.

is

to

do with language,

Scarlet Letter does not take long to

plot very complicated; but

its

Scarlet Letter carefully

a true craftsman can

telling a story.

story of

to realize that

figures of

will

that

is

far

highly

un-

it is

difficult to imi-

recognize

simply because of the surprises

it

how

puts in

of reading, as the expected developments do not occur.

Among its most original features are the development of characters

who are partly realistic and partly stylized, and whose inner states of

mind

are considered far

The

traces of

more important than

an individual

sensibility.

their outer actions.

Once The

Scarlet Letter has

been read and absorbed, a reader can easily recognize other works by

Hawthorne, can even

his

identify individual sentences as the product of

hand. Not only the elaborate yet quiet

setting, situation, characters,

characteristic of this author

and concerns

and no

be extracted from the mixture and,

we

call

style,

in

but configuration of

The

Scarlet Letter are

other. Yet, individual elements can

when we

see

them

in

other writers,

them "Hawthornian." In transcending genres Hawthorne

vented his

own

in-

genre.

Emotional and

intellectual impact.

The emotional impact

of the

novel rises from our engagement in the situation of the major characters,

our appreciation of

their

dilemmas, and our reluctant accep-

tance of their destinies. In the interweaving of choice and fatality

XIX

—

THE SCARLET LETTER

Hawthorne's narrative approaches tragedy. The

rises

from the

impact

intellectual

difficulty of assigning clear praise or

blame

to anyone,

and the consequent necessity of working our way through the myriad

implications and ramifications of the situation

character taken separately, and

together. This

a cast

is

why

of characters.

—the situation of each

the situation that

all

make

of them

book achieves so much depth with so small

the

The

work

intellectual

Hawthorne demands

that

of us enlarges our understanding and distinguishes The Scarlet Letter

from entertainment that leaves us unchanged, although of course

if

Hawthorne would

no entertainment

in

The

not have expected us to read

it.

Certainly part of the "craft" involved

there were

in a

masterwork of

Scarlet Letter

is

the achievement of a satisfying piece of

lives.

For hundreds of thousands of readers

fiction

entertainment.

Touchstones for our

since 1850, the four important characters in

ter

The

—Hes-

Scarlet Letter

Prynne, Arthur Dimmesdale, Roger Chillingworth, and Pearl

have become part of their mental landscape.

sively vengeful

man, they

they hear of an obses-

If

will think of Chillingworth; a beautiful

wild child will remind them of Pearl; reading about a respected

ber of the

community exposed

but

mem-

for a secret sin, they will think of

Dim-

mesdale; and finding themselves in conflict with authority, scorned by

public opinion for doing

tify

As

what they

men

themselves (whether they are

for the

symbol of the

status as shorthand for

believe to be right, they will iden-

or

women) with Hester

scarlet letter itself,

it

Prynne.

has achieved a kind of

any negative labeling imposed on an individual

by his or her surroundings.

A work

that

makes

this

kind of impact on

our self-understanding cannot be anything but important.

Finally, readers usually

expect American masterworks to

something about the country, or

at least to reflect

of being an American. Typically,

tell

them

about the meaning

Hawthorne does not so much

"tell

us" about America as provide the framework within which certain

questions

may

be raised and their answers attempted. His examination

of Puritanism, of

community

Scarlet Letter touches

authority,

on themes

and of individualism

at the center of

American thought.

xx

in

The

American history and

—

The

Critical Reception

Many works

thought to be

literary classics in their

appeared from view while other works ignored

surfaced as classics in later times. The Scarlet Letter

American

literary

remained

also

In fact,

James

it

works

in print

constantly from

first

one of the three partners

the self-doubting author to allow

rather than in a

mixed

thorne thought

it

work was

was:

it

him

was

it

It

was he who persuaded

as a single separate

it

had been

enthusiasm was particularly

Field's

truly "defective" in just the

was not

intense

way Haw-

and dark, sun-

a mixture of bright

and

when

published

in the firm that

to publish

and shadow, humor and pathos,

shine

preferred. Rather,

appearance to the present.

collection of short pieces, as

Hawthorne's original intention.

striking in that the

re-

one of the rare

is

as a classic even before publication,

Hawthorne's works, read the manuscript.

work

dis-

day have

that, recognized as a "classic" at once, has

was recognized

T. Fields,

time have

in their

the taste of the time

as

single in

stress

its

on the dark,

the somber, the gloomy.

It is

throw any cheering

light,"

friend at the time that he finished the

far

which

"positively a hell-fired story, into

possible to

from realizing

his

own

intentions

its

own way

found

it

almost imto a close

work. The sentence suggests that

—which were

to write

The

pleasing and popular, with plenty of variety

stubbornly gone

I

Hawthorne wrote

in the creation.

something

Scarlet Letter

had

Thus, when he read the

conclusion to his wife, he was jubilant to discover

how

deeply

it

af-

fected her. "It broke her heart and sent her to bed with a grievous

headache^which

the

same

may

A

letter.

calculate

I

look upon as a triumphant success!" he wrote

"Judging from

on what bowlers

"ten-strike"

it

its

effect

on her and

in

the publisher,

I

call a ten-strike."

was, so far as Hawthorne's reputation was con-

cerned; for with the publication of The Scarlet Letter he

elevated to the position of the nation's foremost

the popularity that he greatly desired

—

man

was

of letters. But

for financial reasons

cause he had always thought of writing as a

way

instantly

and

of establishing

be-

com-

THE SCARLET LETTER

munity with an audience

The book did not

sell

—did not come with

much over 13,500

and Hawthorne's death thirteen years

ed to

copies between publication

later; his total royalties

more than $1,500. Even allowing

little

sum cannot be regarded as a

owed his continuing reputation to

this

any other work.

this or

amount-

for the uninflated dollar,

significant success.

Hawthorne has

which

the appreciation with

a small

to

The

into being during the 1840s

and

but influential audience has responded to his work, above

all

Scarlet Letter.

Such an audience had

was

chiefly

composed of

come

first

literary critics

who wrote

for

magazines and

newspapers. They had appreciated his 1837 Twice-Told Tales enough

to induce

him

to republish the

had approvingly read

new

his

work

in

an expanded edition

in

writings as they appeared in John L.

O'Sullivans United States Magazine and Democratic Review

1840s; and welcomed the 1846 collection Mosses from an

These

critics

were hoping to find an American writer of

distinct national flavor,

1842;

who was good enough

to be

in the

Old Manse.

fiction

with a

proposed

seri-

ously as an equal to the great English and French novelists of the

among whom were

1840s,

Charles Dickens, William Makepeace

Thackeray, Elizabeth Gaskell, Victor Hugo, and Alexandre Dumas.

James Fenimore Cooper had

doned

from favor because he had aban-

fallen

popular Leatherstocking

his

series

and other

to write polemical novels strongly critical of

Catharine Sedgwick,

who had

torical novelist in the 1820s,

because he believed

in the

had abandoned novel writing

pee

in

for didactic

importance of a "unity of effect" that was

and promising

arrival

in a single sitting.

on the

literary scene

Herman

with Ty-

1846, had quickly become too wild and metaphysical for con-

temporary

work

his-

1849) refused to write novels

in

only attainable in works that could be read

Melville, a recent

American democracy.

been thought equal to Cooper as a

Edgar Allan Poe (who died

tracts.

historical subjects

critical taste.

that critics

flexible

if

The

Scarlet Letter

had been looking

for,

they could safely announce

In addition, a political

before he began

work

it

was not

quite the kind of

but they were prepared to be

as a

major American novel.

scandal had broken around

Hawthorne

just

on The Scarlet Letter: his patronage appointXXll

The

ment

at the

gardless of

Critical Reception

Salem customhouse, which had been assured to him

which party was

re-

power, was terminated when the Whigs

in

beat out the Democrats late in 1848.

A

highly respected literary

man

thus found himself unemployed, with a family to support, in 1849;

and Hawthorne accompanied the

long prefatory essay (called

satirical

account of

life in

The

text of

Scarlet Letter with a

'The Custom-House")

customhouse

the

that provided a

as well as his dismissal.

This topical material assured that the book would be well publicized,

even though

critics

might concentrate on "The Custom-House" rather

than The Scarlet Letter;

it

assured that reviews of the book would be

widely read, and not only by people interested

in literature.

ready to defend the author, others to defend his being

Some were

fired.

Some

people approved of his putting his reactions into print, others thought

it

unseemly of him to have done

House" gave Hawthorne wide

so. But, in

any event, "The Custom-

publicity.

In fact, regardless of their political alignments, leading critics of the

day generally reviewed The Scarlet Letter very favorably, concentrat-

on

ing

and formal perfection,

its stylistic

sight into the

human

soul,

its

its

intensity of effect,

"pathos and power,"

its

its in-

mixture of

solemnity and tenderness, severity and sympathy. While they might

have preferred a work of more humor and playfulness, they found

in

and hap-

The

Scarlet Letter a tragic essence

pily

ranked Hawthorne with leading nineteenth-century European au-

thors.

The

hostile reviews

orientation,

couple

who deemed

— immoral

came from

critics

major

writer,

with a strong religious

— an adulterous

in itself regardless of the author's treatment.

too sympathetically,

among

a

the author's choice of subject

of these thought, in addition, that

ity

worthy of

in a

manner

Hawthorne had

likely to

Many

treated his sinners

encourage similar immoral-

readers.

Hawthorne's subsequent novels were compared

course with The Scarlet Letter.

A number

as

a

matter of

of critics preferred The

House of the Seven Gables. So did Hawthorne, who wrote in a letter

that it was "a more natural and healthy product of my mind/' and

that he "felt less reluctance in publishing

Letter because

it

was

a

more

cheerful

xxin

it"

than he did The Scarlet

book with

a

more varied

tone.

THE SCARLET LETTER

Over

time, however,

The

Scarlet Letter

thorne's

own

self-analysis

came

one that

best of his works, as well as the

to be recognized as the

— notwithstanding

—most represented

his literary

Haw-

methods and

concerns.

In the

decades after Hawthorne's death a group of prestigious Bos-

ton-based literary

tors

were

at

critics

worked

American

as the foremost

work,

tirelessly to

writer.

certain extraneous fac-

canon

chiefly the desire of these critics to develop a

of national literature centering on

when Houghton

maintain his reputation

Once again

Mifflin, a

New

England

writers. In the 1880s,

Boston publishing company, began to put

out elegant editions of the "major" American writers, Hawthorne was

among

the

first

to be featured.

The

success of this effort of critics and

publishers can be measured by the fact that beginning with

James, whose long essay on Hawthorne appeared

in

aspiring novelist-critics, including James, William

Dean Howells, D.

H. Lawrence, Jorge Luis Borges, and John Updike, have

to

Henry

1879, numerous

felt

engage with and write about Hawthorne's achievement.

the need

And

every

general critical study of American literature includes extended discussion of

Hawthorne and The

Scarlet Letter.

James described The Scarlet Letter

tive writing yet

put forth

approach often repeated

as

much with

ticular sensibility. "It

the very heart of

weak than otherwise;

realism of research"

it,

he took an

through the years, identifying

England culture

belonged to the

New

historical novel in the

in criticism

New

general

as "the finest piece of imagina-

in the country." In assessing

soil,

it

as with the author's par-

to the air;

it

came out of

England." While denying that the work was a

normal sense

there

—

is little

— "the

elaboration of detail, of the

James added

there, not only objectively, as

but subjectively as well ...

historical coloring

rather

modern

that, nevertheless, Puritanism "is

Hawthorne had

in the

is

tried to place

very quality of his

own

it

there,

vision."

By

"Puritanism" James did not imply any particular theology, but rather

the intellectual, allegorical quality of the work,

element of cold and ingenious fantasy,

cacy,"

New

which he attributed

its

what he

elaborate imaginative deli-

to the passionless reserve of

England temperament.

XXIV

called "its

Hawthorne's

The

During the

Critical Reception

last thirty years of the

nineteenth century literary

critics

elaborated on an idea of fiction as inclining either to a realist or to a

romantic practice, and Hawthorne came to figure as the ultimate

mantic.

The

difference between these

stituted the fiction.

The

realist

worked

ginning with observed facts of

in the

human

to be truths of

between these truths and the imagined

in the relation

truths; the

two modes was not

was assumed

of subject matter, which

choice

but

life,

facts that con-

inductively, like a scientist, be-

and working from them

life

ro-

romantic worked deductively,

to his

in the reverse direction, be-

ginning with certain truths and using the facts of his story to illustrate

them.

A

might explain why Hawthorne could lean

distinction like this

so heavily

on the

allegorical

and yet create

fantastic, the supernatural, the symbolic,

a sense of truth as strong as in

any

and the

realistic

novel.

Over

tion

time,

came

institution of

American

and perhaps inaccurately, the tradition of American

to be associated with

The

fiction.

Scarlet Letter as the very fountainhead of a truly

(This

an ironic development, since Hawthorne

is

often claimed that his imagination

for the romantic.) In

Scarlet Letter

its

the realist

Dean Howells,

was un-American

as often as

it

was defended,

later nineteenth

for

numerous

century set themselves firm-

camp, among them such important

a great

in its preference

American novel The

role as the quintessential

was attacked

important novelists of the

ly in

admirer of Hawthorne

critics as

who

William

nevertheless re-

garded him as an influence to be overcome. But every essay that

icized

The

The

crit-

Scarlet Letter for excessive fantasy or lack of realism

testified to its

zon.

fic-

romantic practice, which led to the

continuing and powerful presence on the literary hori-

Scarlet Letter continues to be accepted without

an indisputable fictional masterwork of the pre-Civil

this recognition underlies all criticism in the

argument

War

Hawthorne and The

emphasis, viewing the novel

the fascinating psyche of

its

less in

Scarlet Letter

and

and

twentieth century.

Between the turn of the twentieth century and World War

discussion of

era,

as

had

II

much

a biographical

for itself than as an index to

author. Behind a variety of up-to-date

psychological theories such criticism actually returned to the question

XXV

THE SCARLET LETTER

that the earliest reviews

Hawthorne

had

whether the author and

himself:

gloomy. The concern

sively

human

particular

raised, the question that

in

The

Scarlet Letter with the isolation of

on

and

secrets

Hawthorne's personal

of

works were exces-

his

beings from the larger society and the reasons for

that isolation, as well as the focus

expressions

who had

member him; some

in

died almost before

in his

man

in

that the critical

A

critics dealt

by arguing that he was not

balanced

him from

youth; others in the oppressive

Another group of

ity

both his

demand

The

critics

Some found

it

Hawthorne could

in

re-

life

active play at a crucial

New

and

for cheer

his

morbid, but was a well-

works;

still

1

the

is,

others maintained

and balance was naive and narrow.

Scarlet Letter obviously

thorne's "ambiguity,' that

England heritage.

with Hawthorne's supposed morbidin the least

powerful way of accounting for the differing

a reading of

and

an allegedly eccentric and withdrawn mother;

others in the foot injury that kept

time

were taken as

guilt,

maladjustment,

searched the biographical records for explanation.

the absent father

had so worried

way

in

critical

responses that

produced was to

which he makes

stress

it

Haw-

difficult or

impossible to extract a clear and particular "message" from his work.

Studies of the

means by which such ambiguity was achieved became,

1950s, the chief

in the

The upshot

way

of investigating the text

of such studies

was

itself.

a supplanting of the

view of

Haw-

a technique for impos-

thorne as romantic allegorist (since allegory

is

ing single, clear meanings) with the idea of

Hawthorne

as symbolist.

less interested in

Hawthornes

In line

with such a change,

critics

grew

use of earlier sources (Milton, Spenser, John Bunyan, and the like) and

more

interested in his influence

on

later writers;

where he had often

been thought of as creating a deliberately archaic kind of

was now

perceived

in the

fiction,

he

opposite light: as the forerunner of various

modern techniques. An important 1957 study by Charles

Symbolism and American

Literature,

made

this

Feidelson,

point especially

strongly.

Some

critics,

accepting the notion of Hawthorne's personal isolation

its

causative

power

shortcomings

in society

rather than in the

in life

and

in his

xxvi

work, attributed

man. More

his situation to

specifically they

The

Critical Reception

pointed either to his dissent from the obligatory optimism of midnineteenth-century America, which required belief in progress and hu-

man

perfectibility as articles of faith, or to his difficult situation as a

"serious" artist in a society that loved trivia. In such interpretations,

as

"blame"

shifts

from Hawthorne to

psychological to the sociological, and

stood not as an explorer of general

This

society,

Hawthorne begins

human

it

criticism a desire to fold the particular

work

The blending of an

in

The

its

earlier idea of

Hawthorne's "romantic"

strongest and

most

presumed

work had

American and

gorical novel

as

Its

Tradition.

prime goal to establish a distinction between

its

British fiction.

Chase called The Scarlet Letter an

whose "allegory both

Puritanism" and whose theme

involved in the

social

influential statements

Richard Chase's 1957 study, The American Novel and

This

The

into a larger field of in-

Scarlet Letter with a later sense of his

purpose received one of

in

in criticism of

shares with the biographical

Scarlet Letter in the last forty years, but

method

to be under-

truths, but as a social critic.

probably the most important development

is

quiry.

emphasis veers from the

abandonment

is

in

alle-

form and substance derives from

the "loss or submergence of emotion

of the

Old World

Again, however, the characteristics of the

cultural heritage."

work

itself

came

into play

because interpretations of The Scarlet Letter as social commentary

ambiguity any more than could the

could not escape the

text's

biographical criticism.

Where one

Hawthorne:

A

Critical Study)

fashioned conservative

who

critic

(e.g.,

Hyatt Waggoner

in

might present Hawthorne as an old-

did not believe in

human

goodness, and

who

exploited Puritanism as a corrective to his age, another

(e.g.,

D. H. Lawrence

in Studies in Classic

critic

American Literature) might

argue with equal force and passion that The Scarlet Letter was a pro-

found although disguised attack on an emotionally impoverishing and

hypocritical

American moralism.

Hawthorne's ambiguity entered Chase's interpretation, too,

in that

Chase decided Hawthorne had not committed himself as to whether

the loss of the

Old World heritage was good or bad

Following Chase, any number of

in

critics

America, 1969) to Michael Davitt

for Americans.

from Joel Porte [The Romance

Bell

{The Development of Amer-

THE SCARLET LETTER

Romance, 1981) have interpreted The

icon

whose form

ciety

particularly "American,"

is

from an alienated perspective that

and professional

work

Scarlet Letter as a

whose point

reflects

is

to criticize so-

Hawthornes personal

situation.

Along with the

The

interest in assimilating

more

Scarlet Letter to

general inquiry, biographical and social criticism share an approach to

the

work

different

as an entity to be "interpreted." This

from that prevailing

work was considered

in relation to its ability to

encoding a message for the

tions, not as a text

The many

view to "the text

itself"

and correct "meaning"

Two

The

for

engage reader emo-

have also shared

is

who

have

this preoc-

come up with

a

Scarlet Letter.

questions have especially preoccupied them.

Hawthorne's worldview

strikingly

where the

intellect to decipher.

cupation with interpretation and have attempted to

basic

is

time,

second half of the twentieth century

critics in the

restricted their

approach

Hawthornes own

in

One

essentially religious or secular,

is

whether

whether he

thinks that his characters have "sinned" in the sense of breaking a

divine

commandment

a social law.

A

or whether, instead, he thinks they have broken

second, connected question

Hawthorne sympathize

with, and

vary widely; there are those

who

is:

which characters does

why? Answers

see Hester as

to these questions

an out-and-out secular

heroine standing up for the individual against arbitrary authority, and

those

who

see her as a religious sinner, adding pride

original trespass.

Those who are committed

Hawthorne take The

of the inner

life;

strength rather in

and anger

to her

to a secular reading of

Scarlet Letter as a powerful psychological study

those committed to a religious reading find

Hawthornes

its

rejection of his characters' rationali-

zations, his adherence to an ethical absolutism based

on

belief in a

human desire.

so many different,

firm divine order that takes precedence over

The

fact that critics

fensible, readings of

ter

of

could come up with

The

Hawthornes ambiguity, but with

contemporary

critics

linguistic texts;

yet de-

Scarlet Letter eventually led again to the mat-

now

a

few new

believe that ambiguity

because language

ing the language in which critics

itself is

make

XXVI 11

is

twists.

inescapable

Some

in all

inherently unstable (includ-

their arguments),

no "interpre-

The

Critical Reception

tation" can ever be definitively established as the right one. Even those

who

prefer to think of language as

the world of a

complex

and

to be so resonant

more

The

Some

is

many

simply

will

elements in the mixture. For ex-

sensitivities to different

ample, in recent years feminist

it

bound

is

responses will be overly

personal, and hence "unauthorized" by the text, but

because

agree that

Scarlet Letter

rich in connotations that different readers will

necessarily have different responses.

be based on

may

solid than this

fictional text like

critics

have turned to The Scarlet Letter

one of the few acknowledged American masterworks

War whose main character is a woman. A feminist perspective allows one to see how Hawthorne was concerned, in

developing Hester, with the question of the status of women in society,

as well as the different commitments men and women tend to make

from before the

Civil

to romantic love. Since romantic love serves Hester so badly, they can

Hawthorne's

identify a previously unnoticed aspect of

social criticism:

the idea of romantic love as a trick to ensure the willing subservience

of

women

to the social system. This feminist perspective responds to

elements truly there but completely invisible to those looking only for

a theological statement in the novel.

Perhaps, then, the most exciting thing about The Scarlet Letter

we can

not that

translate

meanings; though

each reader

a

it

into a core meaning, but that

dead work

if it is

in a slightly different

not read,

way, just as

each other. The elusiveness of the text

for

its

are

human

ways

in

our

own

life

for

thus the essential reason

all,

The

Scarlet Letter creates a

way, indeed that each of us

at different points in

our

anarchistic subjectivity here; rather

lives.

we

We

were,

we would

message, and

it

may

would have no capacity

XXIX

world that we

enter in differ-

do not surrender

work

never return to a masterpiece after

reading.

their

to an

recognize that interpretation

not the "last word" in an encounter with a great

its

to

beings do for

skimmed and discarded when we have extracted

"message" once and for

each enter

it

comes

continuing fascination throughout the years. Unlike simpler

works that

ent

is

it

is

of

full

it is

to

move

of literature.

we had

is

If

learned

us after the

first

WHAT?

THE STORY

When

we

begin to read a novel

through words.

on

its

own

If it

we

enter an imaginary world created

works, the novel persuades us to accept that world

terms, for the duration of the reading, no matter

mote or farfetched that created world may

out of our surroundings

rative art.

We

is

part of the

leave the real world,

immense

more or

how

be. This ability to

re-

lift

us

attractiveness of nar-

less quickly,

more or

less

comfortably, partly with the aid of conventions about fiction learned

so long ago, and so often repeated, that they have

fectly natural.

titled

No

"real world," for

chapters; yet a novel without

come

example, comes

in

to

seem per-

numbered or

them would seem unnatural. While

depending on such shared conventions, however, each novel

unique, and must instruct readers specifically in

world. Thus every good novel, whether a

or a would-be classic,

tells

us

how

it

intensely than in the opening pages.

how

also

to live in

its

of transient popularity

should be read, and never more

If it

with readers at the beginning, the novel

end.

work

is

does not establish rapport

may have no

readers at the

THE SCARLET LETTER

ON THE THRESHOLD

The

In

Scarlet Letter a very brief

and two longish paragraphs

tence,

opening section

—

is

—one separate

set apart as a first chapter.

sen-

Such

emphasis, for an amount of prose that would normally be simply part

of a longer chapter, says something about the pacing of the whole

work:

novel will proceed deliberately, with pauses along the way.

this

Indeed, in the

arrest, as a

to begin.

we

sentence

find ourselves present at a

crowd of people waits

our

If

book work

we

first

who

we too

will

be put

are these people?

in a

where are we?

of them, that a story engages the attention

The

we are inclined to let the

mood of anticipation. And

if

and the more or

implicit raising of questions,

less

and

It is

through the

delayed answering

interest of

sentence does say something about where

first

of

something to happen, something

fictional senses are keen,

its spell,

will ask:

for

moment

we

its

readers.

are:

it

pro-

— "sad-colored

vides

the description of the people's clothing

steeple-crowned hats" — and

reference

garments and

clues in

gray,

"wooden

edifice"

in

and

with iron spikes" (47).

er,

door "heavily timbered with oak, and studded

a

Men

don't wear steeple-crowned hats any long-

nor are buildings made with doors

but was

in the past;

it

like the

when

that, like us,

The

first

"some

we know

does

fifteen or

Any

next

twenty years after the settlement of

set in present

the action of his story.

time for any reader.

sentence goes beyond intimations about historical time and

this

tell

us something about the kind of world

list

we

are

by mixing straightforward description with connotative

terms that imply attitudes.

giving us a

sified

are

Hawthorne was addressing an audience

that

was never

place and begins to

in. It

this are settled in the

was not contemporaneous with

Scarlet Letter

The

We

the narrator refers to "the forefathers of Boston" and

locates the action

the town." So

one described.

the past to Hawthorne's contemporaries?

doubts a reader of today might have about

paragraph,

to a

its

of colors.

It

uses the phrase "sad-colored" rather than

The impression created by

the term

is

inten-

by the description of the door: heavily timbered, studded with

iron spikes.

Even

we recognize an atmosphere

antagonism. And we recognize that we

this early in the story

of sadness, of oppression, of

What? The

must read not only

for historical detail, but also for

sphere; perhaps the

mative than the

Story

mood and atmosphere

will be

even more infor-

detail.

The atmosphere continues

to build in the next sentence,

human

colony, whatever Utopia of

which be-

"The founders of

gins the second paragraph of this brief chapter:

new

mood and atmo-

a

and happiness they

virtue

might originally project, have invariably recognized

it

among

their

earliest practical necessities to allot a portion of the virgin soil as a

cemetery, and another portion as the

where

sentence, placed

immediately that

we

purpose (and even

if

it

new

are in a

we

site

of a prison" (47). This one

performs a number of tasks.

is,

did not

colony, founded for

know what

It tells

us

some Utopian

a "utopia" was,

we

could

conclude from the terms "virtue" and "happiness" that the colony had

been founded for

But

idealistic reasons).

in this colony, like all others

(says the narrator), certain inescapable realities

selves very early on.

Death and crime, the

virtue,

have forced the founders

alistic"

group of

idealists

—

to

in

question the possibility of

of

The

Scarlet Letter

may

antithesis of happiness

and

— unless they were a particularly

"re-

modify

all

is

it is

their plans.

Utopias,

At once, then,

is

it

puts

and suggests that the "story"

be about things going wrong

Utopia. Such an interpretive frame

ting itself;

have manifested them-

not inherent

in a

projected

in the historical set-

created by the connotative words in which the setting

conveyed.

The reader can

the

first

tence,

also recognize a

change

to the second sentence of

though

the scene,

is

it

contains

it

—descriptive—

contains

some

of interpretive commentary. Thus,

will

move

freely in

procedure from

"The Prison-Door." The

some words suggesting an

mainly expository

reverses the emphasis;

in narrative

we

first

sen-

interpretation of

in its nature.

The second

exposition, but consists mostly

recognize that this narration

and out of the action,

will

supplement the action

with various kinds of commentary ranging from opinion on the spe-

way

cific

action

to large-scale generalizations

about universals.

The

action, apparently, will be strongly mediated by

commentary pro-

all

the

vided by a narrator who, rather than concealing himself, will regularly

stress his presence.

THE SCARLET LETTER

Why

should a writer create so prominent a narrator?

for the reader,

to

and

a sign of

themselves?

tell

Through such narrators

though

it

though not

were

skill in

was conventional

It

time to have narrators

as

more

who

Isn't

better

it

appear

stories

Hawthorne's

for the novel of

the novel-reading experience

is

was presented

where the

storytelling experience,

a

if

conversed freely with their readers.

a character in the action,

transaction. But

the writer,

storyteller,

a crucial figure in the narrative

Hawthorne may have had

particular reasons for de-

ploying a highly visible narrator in The Scarlet Letter, reasons that

made

it

wise to establish the narrator's presence as quickly as possible.

time period and culture of his story

First, the

come

quite distant to his audience, requiring a

may have

good deal of explana-

make these comprehensible. Second, the story

tell may have been sufficiently unconventional to call

making sure that the readers knew how to respond.

tion to

In just

two sentences Hawthorne has conveyed

what readers

are to read

are to expect in

it.

the sentences,

a

Reflecting on

The

Scarlet Letter,

we may suppose

that

The

a long

book

by word.

speak

—of

it is

and thus how they

has packed into

all

is

going to be

the time. This

is

not

one to be unpacked word

not to be read for the action alone, but also for the

and resonances

—the

narrative

embroidering,

so

to

that action.

The second paragraph goes on

The "new colony"

(the

for extra help in

Scarlet Letter

to be dipped into, but a short

And

implications

that he wants to

a greal deal about

how much Hawthorne

compressed work with a greal deal going on

already be-

is

to specify the setting in

Boston, about twenty years after

colony was established

in

1630).

Isaac Johnson, King's Chapel. For

We

it

more

detail.

was

settled

read the names Cornhill,

most of us these

allusions cannot

do more than supply the impression of accuracy, encouraging

that the narrator

is

well informed.

We would

a belief

prefer to take a historical

guided tour from a trustworthy person, and a few such specific

refer-

many of them might proconfused sense that we are not reading a novel

research has indicated, by the way, that Haw-

ences inspire the requisite confidence. (Too

duce boredom, or a

after

all.)

Scholarly

thorne did turn to historical sources for information of

this sort,

even

What? The

Story

though he does not always follow them. The references to the layout

of early Boston are correct.

The paragraph

and continues

also goes

work

its

which the action

is

to imply

more about

the action to come,

of creating an interpretive perspective through

to be viewed.

Why would

a prison.

on

The building we stand

people have assembled