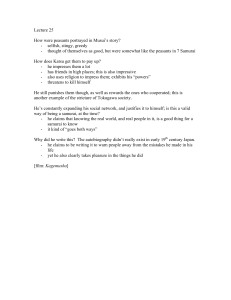

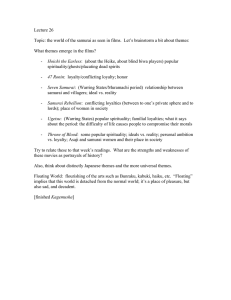

The Book of Bushido: Samurai Honor & Chivalry

advertisement